CHAPTER XI

Spain

1300–1517

I. THE SPANISH SCENE: 1300–1469

SPAIN’S mountains were her protection and tragedy: they gave her comparative security from external attack, but hindered her economic advance, her political unity, and her participation in European thought. In a little corner of the northwest a half-nomad population of Basques led their sheep from plains to hills and down again with the diastole and systole of the seasons. Though many Basques were serfs, all claimed nobility, and their three provinces governed themselves under the loose sovereignty of Castile or Navarre. Navarre remained a separate kingdom until Ferdinand the Catholic absorbed its southern part into Castile (1515), while the rest became a kingly appanage of France. Sardinia was appropriated by Aragon in 1326; the Baleares followed in 1354, Sicily in 1409. Aragon itself was enriched by the industry and commerce of Valencia, Tarragona, Saragossa, and Barcelona—capital of the province of Catalonia within the kingdom of Aragon. Castile was the strongest and most extensive of the Spanish monarchies; it ruled the populous cities of Oviedo, León, Burgos, Valladolid, Salamanca, Cordova, Seville, and Toledo, its capital; its kings played to the largest audience, and for the greatest stakes, in Spain.

Alfonso XI (r. 1312–50) improved the laws and courts of Castile, deflected the pugnacity of the nobles into wars against the Moors, supported literature and art, and rewarded himself with a fertile mistress. His wife bore him one legitimate son, who grew up in obscurity, neglect, and resentment, and became Pedro el Cruel. Peter’s accession at fifteen (1350) so visibly disappointed the nine bastards of Alfonso that they were all banished, and Leonora de Guzman, their mother, was put to death. When Peter’s royal bride, Blanche of Bourbon, arrived unsolicited from France, he married her, spent two nights with her, had her poisoned on a charge of conspiracy (1361), and married his paramour Maria de Padilla, whose beauty, legend assures us, was so intoxicating that the cavaliers of the court drank with ecstasy the water in which she had bathed. Pedro was popular with the lower classes, which supported him to the very bitter end; but the repeated attempts of his half-brothers to depose him drove him to such a series of treacheries, murders, and sacrileges as would clog and incarnadine any tale. Finally Henry of Trastamara, Leonora’s eldest son, organized a successful revolt, slew Peter with his own hand, and became Henry II of Castile (1369).

But we do nations injustice when we judge them from their kings, who agreed with Machiavelli that morals are not made for sovereigns. While the rulers played with murder, individual or nationalized, the people, numbering some 10,000,000 in 1450, created the civilization of Spain. Proud of their pure blood, they were an unstable mixture of Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Visigoths, Vandals, Arabs, Berbers, and Jews. At the social bottom were a few slaves, and a peasantry that remained serf till 1471; above them were the artisans, manufacturers, and merchants of the towns; above these, in rising layers of dignity, were the knights (caballeros), the nobles dependent upon the king (hidalgos), and the independent nobles (proceres); and alongside these laymen were grades of clergy mounting from parish priests through bishops and abbots to archbishops and cardinals. Every town had its conseijo or council, and sent delegates to join nobles and prelates in provincial and national cortes; in theory the edicts of the kings required the consent of these “courts” to become laws. Wages, labor conditions, prices, and interest rates were regulated by municipal councils or the guilds. Trade was hampered by royal monopolies, by state or local tolls on imports and exports, by diverse weights and measures, by debased currencies, highway brigands, Mediterranean pirates, ecclesiastical condemnation of interest, and the persecution of Moslems—who manned most industry and commerce—and Jews, who managed finance. A state bank was opened in Barcelona (1401) with governmental guarantee of bank deposits; bills of exchange were issued; and marine insurance was established by 1435.1

As the Spaniards mingled anti-Semitism with Semitic ancestry, so they retained the heat of Africa in their blood, and were inclined, like the Berbers, to rarity and violence of action and speech. They were sharp and curious of mind, yet eagerly credulous and fearfully superstitious. They sustained a proud independence of spirit, and dignity of carriage, even in misfortune and poverty. They were acquisitive and had to be, but they did not look down upon the poor, or lick the boots of the rich. They despised and deferred labor, but they bore hardship stoically; they were lazy, but they conquered half the New World. They thirsted for adventure, grandeur, and romance. They relished danger, if only by proxy; the bullfight, a relic of Crete and Rome, was already the national game, formal, stately, colorful, exacting, and teaching bravery, artistry, and an agile intelligence. But the Spaniards, like the modern (unlike the Elizabethan) English, took their pleasures sadly; the aridity of the soil and the shadows of the mountain slopes were reflected in a dry somberness of mood. Manners were grave and perfect, much better than hygiene; every Spaniard was a gentleman, but few were knights of the bath. Chivalric forms and tourneys flourished amid the squalor of the populace; the “point of honor” became a religion; women in Spain were goddesses and prisoners. In the upper classes, dress, sober on weekdays, burst into splendor on Sundays and festive occasions, flaunting silks and ruffs and puffs and lace and gold. The men affected perfume and high heels, and the women, not content with their natural sorcery, bewitched the men with color, lace, and mystic veils. In a thousand forms and disguises the sexual chase went on; solemn ecclesiastical terrors, lethal laws, and the punto de onor struggled to check the mad pursuit, but Venus triumphed over all, and the fertility of women outran the bounty of the soil.

The Church in Spain was an inseparable ally of the state. It took small account of the Roman pope; it made frequent demands for the reform of the papacy, even while contributing to it the unreformable Alexander VI; in 1513 Cardinal Ximenes forbade the promulgation in Spain of the indulgence offered by Julius II for rebuilding St. Peter’s.2 In effect the king was accepted as the head of the Spanish Church; in this matter Ferdinand did not wait for Henry VIII to instruct him; no Reformation was needed in Spain to make state and Church, nationalism and religion, one. As part of the unwritten bargain the Spanish Church enjoyed substantial prerogatives under a government consciously dependent upon it for maintaining moral order, social stability, and popular docility. Its personnel, even in minor orders, were subject only to ecclesiastical courts. It owned great tracts of land, tilled by tenants; it received a tenth of the produce of other holdings, but paid a third of this tithe to the exchequer; otherwise it was exempt from taxation.3 It was probably richer, in comparison with the state, than in any other country except Italy.4 Clerical morals and monastic discipline were apparently above the medieval average; but, as elsewhere, clerical concubinage was widespread and condoned.5 Asceticism continued in Spain while declining north of the Pyrenees; even lovers scourged themselves to melt the resistance of tender, timid señoritas, or to achieve some masochistic ecstasy.

The people were fiercely loyal to Church and king, because they had to be in order to fight with courage and success their immemorable enemies the Moors; the struggle for Granada was presented as a war for the Holy Faith, Santa Fé. On holy days men, women, and children, rich and poor, paraded the streets in solemn procession, somberly silent or chanting, behind great dolls (pasos) representing the Virgin or a saint. They believed intensely in the spiritual world as their real environment and eternal home; beside it earthly life was an evil and transitory dream. They hated heretics as traitors to the national unity and cause, and had no objection to burning them; this was the least they could do for their outraged God. The lower classes had hardly any schooling, and this was nearly all religious. Stout Cortes, finding among the pagan Mexicans a rite resembling the Christian Eucharist, complained that Satan had taught it to them just to confuse the conquerors.6

The intensity of Catholicism in Spain was enhanced by economic competition with Moslems and Jews, who together made up almost a tenth of the population of Christian Spain. It was bad enough that the Moors held fertile Granada; but more closely irritating were the Mudejares—the unconverted Moors who lived among the Spanish Christians, and whose skill in business, crafts, and agriculture was the envy of a people mostly bound in primitive drudgery to the soil. Even more unforgivable were the Spanish Jews. Christian Spain had persecuted them through a thousand years: had subjected them to discriminatory taxation, forced loans, confiscations, assassinations, compulsory baptism; had compelled them to listen to Christian sermons, sometimes in their own synagogues, urging their conversion, while the law made it a capital crime for a Christian to accept Judaism. They were invited or conscripted into debates with Christian theologians, where they had to choose between a shameful defeat or a perilous victory. They and the Mudejares had been repeatedly ordered to wear a distinctive badge, usually a red circle on the shoulder of their garments. Jews were forbidden to hire a Christian servant; their physicians were not allowed to prescribe for Christian patients; their men, for cohabiting with a Christian woman, were to be put to death.

In 1328 the sermons of a Franciscan friar goaded the Christians of Estella, in Navarre, to massacre 5,000 Jews and burn down their houses.7 In 1391 the sermons of Fernán Martínez aroused the populace in every major center of Spain to massacre all available Jews who refused conversion. In 1410 Valladolid, and then other cities, moved by the eloquence of the saintly and fanatical Vicente Ferrer, ordered the confinement of Jews and Moors within specified quarters—Juderia or alhama—whose gates were to be closed from sunset to sunrise; this segregation, however, was probably for their protection.8

Patient, laborious, shrewd, taking advantage of every opportunity for development, the Jews multiplied and prospered even under these disabilities. Some kings of Castile, like Alfonso XI and Pedro el Cruel, favored them and raised brilliant Jews to high places in the government. Alfonso made Don Joseph of Écija his minister of finance, and another Jew, Samuel ibn-Wakar, his physician; they abused their position, were convicted of intrigue, and died in prison.9 Samuel Abulafia repeated the sequence; he became state treasurer under Pedro, amassed a large fortune, and was put to death by the King.10 Three years earlier (1357) Samuel had built at Toledo a classically simple and elegant synagogue, which was changed under Ferdinand into the Christian church of El Transito, and is now preserved by the government as a monument of Hebraeo-Moorish art in Spain. Pedro’s protection of the Jews was their misfortune: when Henry of Trastamara deposed him 1,200 Jews were massacred by the victorious soldiers (Toledo, 1355); and worse slaughters ensued when Henry brought into Spain the “Free Companions” recruited by Du Guesclin from the rabble of France.

Thousands of Spanish Jews preferred baptism to the terror of abuse and pogroms. Being legally Christians, these Conversos made their way up the economic and political ladder, in the professions, even in the Church; some became high ecclesiastics, some were counselors to kings. Their talents in finance earned them invidious prominence in the collection and management of the national revenue. Some surrounded themselves with aristocratic comforts, some made their prosperity offensively conspicuous. Angry Catholics fastened upon the Conversos the brutal name of Marranos—swine.11 Nevertheless Christian families with more pedigree than cash, or with a prudent respect for ability, accepted them in marriage. In this way the Spanish people, especially the upper classes, received a substantial infusion of Jewish blood. Ferdinand the Catholic and Torquemada the Inquisitor had Jews in their ancestry.12 Pope Paul IV, at war with Philip II, called him and the Spanish the “worthless seed of the Jews and Moors.”13

II. GRANADA: 1300–1492

Ibn-Batuta described the situation of Granada as “unequaled by any city in the world.... . Around it on every side are orchards, gardens, flowering meadows, vineyards”; and in it “noble buildings.”14 Its Arabic name was Karnattah—of uncertain meaning; its Spanish conquerors christened it Granada—“full of seeds”—probably from the neighboring abundance of the pomegranate tree. The name covered not only the city but a province that included Xeres, Jaén, Almería, Málaga, and other towns, with a total population of some four millions. The capital, with a tenth of these, rose “like a watchtower” to a summit commanding a magnificent valley, which rewarded careful irrigation and scientific tillage with two crops a year. A wall with a thousand towers guarded the city from its encompassing foes. Mansions of spacious and elegant design sheltered the aristocracy; in the public squares fountains cooled the ardor of the sun; and in the fabulous hails of the Alhambra the emir or sultan or caliph held his court.

A seventh of all agricultural produce was taken by the government, and probably as much by the ruling class as a fee for economic management and military leadership. Rulers and nobles distributed some of their revenue to artists, poets, scholars, scientists, historians, and philosophers, and financed a university where learned Christians and Jews were allowed to hold chairs and occasional rectorships. On the college portals five lines were inscribed:

“The world is supported by four things: the learning of the wise, the justice of the great, the prayers of the good, and the valor of the brave.”15 Women shared freely in the cultural life; we know the names of feminine savants of Moorish Granada. Education, however, did not prevent the ladies from stirring their men not only to swelling passions but to chivalric devotion and displays. Said a gallant of the time: “The women are distinguished for the symmetry of their figures, the gracefulness of their bodies, the length and waviness of their hair, the whiteness of their teeth, the pleasing lightness of their movements... the charm of their conversation, and the perfume of their breath.”16 Personal cleanliness and public sanitation were more advanced than in contemporary Christendom. Dress and manners were splendid, and tournaments or pageants brightened festive days. Morals were easy, violence was not rare, but Moorish generosity and honor won Christian praise. “The reputation of the citizens” of Granada “for trustworthiness,” said a Spanish historian, “was such that their bare word was more relied on than a written contract is among ourselves.”17 Amid these high developments the growth of luxury sapped the vigor of the nation, and internal discord invited external attack.

Christian Spain, slowly consolidating its kingdoms and increasing its wealth, looked with envious hostility upon this prosperous enclave, whose religion taunted Christianity as an infidel polytheism, and whose ports offered dangerous openings to an infidel power; moreover, those fertile Andalusian fields might atone for many a barren acre in the north. Only because Catholic Spain was divided among factions and kings did Granada retain its liberty. Even so the proud principality agreed (1457) to send annual tribute to Castile. When a reckless emir, Ali abu-al-Hasan, refused to continue this bribe to peace (1466), Henry IV was too busy with debauchery to compel obedience. But Ferdinand and Isabella, soon after their accession to the throne of Castile, sent envoys to demand resumption of the tribute. With fatal audacity Ali replied: “Tell your sovereigns that the kings of Granada who paid tribute are dead. Our mint now coins nothing but sword blades! “18 Unaware that Ferdinand had more iron in him than was in the Moorish mint, and claiming provocation by Christian border raids, abu-al-Hasan took by assault the Christian frontier town of Zahara, and drove all its inhabitants into Granada to be sold as slaves (1481). The Marquis of Cádiz retaliated by sacking the Moorish stronghold of Alama (1482). The conquest of Granada had begun.

Love complicated war. Abu-al-Hasan developed such an infatuation for one of his slaves that his wife, the Sultana Ayesha, roused the populace to depose him and crown her son abu-’Abdallāh, known to the West as Boabdil (1482). Abu-al-Hasan fled to Málaga. A Spanish army marched to besiege Málaga; it was almost annihilated in the mountain passes of the Ajarquia range by troops still loyal to the fallen emir. Jealous of his father’s martial exploits, Boabdil led an army out from Granada to attack a Christian force near Lucena. He fought bravely, but was defeated and taken prisoner. He obtained his release by promising to aid the Christians against his father, and to pay the Spanish government 12,000 ducats a year. In the meantime his uncle Abu-Abd-Allahi, known as Az-Zaghral (the Valiant), had made himself emir of Granada. A three-cornered civil war ensued among uncle, father, and son for the Granadine throne. The father died, the son seized the Alhambra, the uncle retired to Guadix, whence he emerged repeatedly to attack Spaniards wherever he could find them. Stirred to imitation, Boabdil repudiated pledge and tribute, and prepared his capital to resist inevitable assault.

Ferdinand and Isabella deployed 30,000 men to devastate the plains that grew Granada’s food. Mills, granaries, farm houses, vineyards, olive and orange groves were destroyed. Málaga was besieged to prevent its receiving or sending supplies for Granada; it held out until its population had consumed all available horses, dogs, and cats, and were dying by hundreds of starvation or disease. Ferdinand forced its unconditional surrender, condemned the 12,000 survivors to slavery, but allowed the rich to ransom themselves by yielding up all their possessions. Az-Zaghral submitted. The entire province of Granada outside its capital was now in Christian hands.

The Catholic sovereigns built around the beleaguered citadel a veritable city for their armies, called it Santa Fé, and waited for starvation to deliver the “pride of Andalusia” to their mercy. Moorish cavaliers rode out from Granada and dared Spanish knights to single battle; the knights responded with equal gallantry; but Ferdinand, finding that his best warriors were being killed one by one on this chivalric plan, put an end to the game. Boabdil led out his troops in a forlorn sally, but they were beaten back. Appeals for help were sent to the sultans of Turkey and Egypt, but no help came; Islam was as divided as Christendom.

On November 25, 1491, Boabdil signed terms of capitulation that did rare honor to the conquerors. The people of Granada were to keep their property, language, dress, religion, ritual; they were to be judged by their own laws and magistrates; no taxes were to be imposed till after three years, and then only such as Moslem rulers had levied. The city was to be occupied by the Spanish, but all Moors who wished to leave it might do so, and transportation would be provided for those who wished to cross to Moslem Africa.

Nevertheless the Granadines protested Boabdil’s surrender. Insurrection so threatened him that he turned the keys of the city over to Ferdinand (January 2,1492), and rode through the Christian lines, with his relatives and fifty horsemen, to the little mountain principality which he was to rule as a vassal of Castile. From the crags over which he passed he turned to take a last look at the wonderful city that he had lost; that summit is still called El Ultimo Sospiro del Moro—the Last Sigh of the Moor. His mother reproved him for his tears: “You do well to weep like a woman for what you could not defend as a man.”19

Meanwhile the Spanish army marched into Granada. Cardinal Mendoza raised a great silver cross over the Alhambra, and Ferdinand and Isabella knelt in the city square to give thanks to the God who after 781 years had evicted Islam from Spain.

III. FERDINAND AND ISABELLA

The century between the death of Henry of Trastamara (1379) and the accession of Ferdinand to the throne of Aragon was a fallow time for Spain. A series of weak rulers allowed the nobles to disorder the land with their strife; government was negligent and corrupt; private vengeance was uncurbed; civil war was so frequent that the roads were unsafe for commerce, and the fields were so often despoiled by armies that the peasants left them untilled. The long reign of John II (1406–54) of Castile, who loved music and poetry too much to care for the chores of state, was followed by the disastrous tenure of Henry IV, who by his administrative incompetence, his demoralization of the currency, and his squandering of revenue on favored parasites, earned the title of Enrique el Impotente. He willed his throne to Juana, whom he called his daughter; the scornful nobles denied his parentage and potency, and forced him to name his sister Isabella as his successor. But at his death (1474) he reaffirmed Juana’s legitimacy and her right to rule. It was out of this paralyzing confusion that Ferdinand and Isabella forged the order and government that made Spain for a century the strongest state in Europe.

The diplomats prepared the achievement by persuading Isabella, eighteen, to marry her cousin Ferdinand, seventeen (1469). Bride and bridegroom were both descended from Henry of Trastamara. Ferdinand was already King of Sicily; on the death of his father he would be also King of Aragon; the marriage, therefore, wed three states into a powerful kingdom. Paul II withheld the papal bull needed to legalize the marriage of cousins; the requisite document was forged by Ferdinand, his father, and the archbishop of Barcelona;20 after the fait had been accompli a genuine bull was obtained from Pope Sixtus IV. A more substantial difficulty lay in the poverty of the bride, whose brother refused to recognize the marriage, and of the bridegroom, whose father, immersed in war, could not afford a royal ceremony. A Jewish lawyer smoothed the course of true politics with a loan of 20,000 sueldos, which Isabella repaid when she became Queen of Castile (1474).*

Fig. 25—HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER: Edward VI, aged six. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

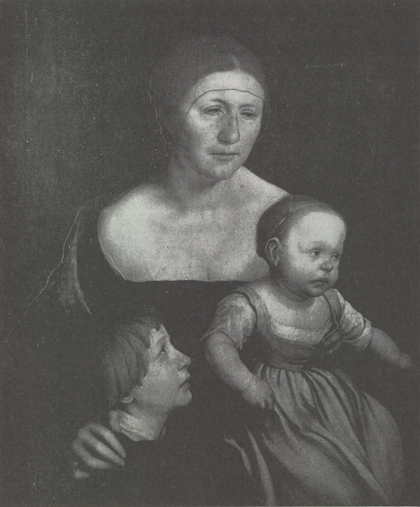

Fig. 26—HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER: Family of the Artist. Museum, Basel

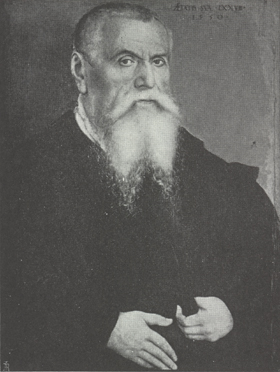

Fig. 27—LUCAS CRANACH: Self-Portrait. Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Fig. 28—TITIAN: Paul III and His Nepbews. National Museum, Naples

Fig. 29—Cathedral (main chapel), Seville

Fig. 31—HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER: Henry VIII. Corsini Gallery, Rome

Fig. 32—AFTER HOLBEIN: Thomas More and His Family. National Portrait Gallery, London

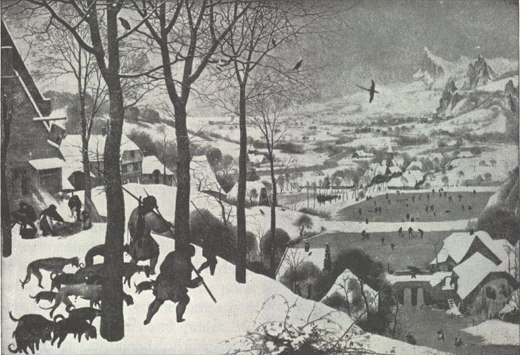

Fig. 33—PIETER BRUEGHEL THE ELDER: Hunters in the Snow. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

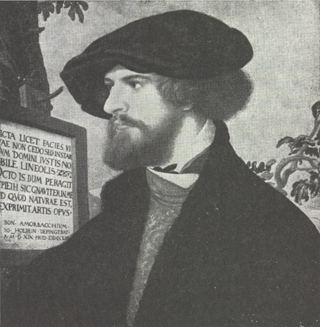

Fig. 34—HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER: Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach. Museum, Basel

Fig. 35—ANONYMOUS PAINTER OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY: Rabelais. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva

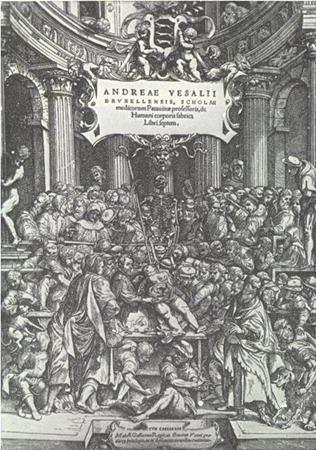

Fig. 36—TITLE PAGE OF VESALIUS’ De humani corporis fabrica

Her right to the throne was challenged by Affonso V of Portugal, who had married Juana. War decided the issue at Toro, where Ferdinand led the Castilians to victory (1476). Three years later he inherited Aragon; all Spain except Granada and Navarre was now under one government. Isabella remained only Queen of Castile; Ferdinand ruled Aragon, Sardinia, and Sicily, and shared in ruling Castile. The internal administration of Castile was reserved to Isabella, but royal charters and decrees had to be signed by both sovereigns, and the new coinage bore both the regal heads. Their complementary qualities made Ferdinand and Isabella the most effective royal couple in history.

Isabella was incomparably beautiful, said her courtiers—that is, moderately fair; of medium stature, blue eyes, hair of chestnut brown verging on red. She had more schooling than Ferdinand, with a less acute and less merciless intelligence. She could patronize poets and converse with cautious philosophers, but she preferred the company of priests. She chose the sternest moralists for her confessors and guides. Wedded to an unfaithful husband, she seems to have sustained full marital fidelity to the end; living in an age as morally fluid as our own, she was a model of sexual modesty. Amid corrupt officials and devious diplomats, she herself remained frank, direct, and incorruptible. Her mother had reared her in strict orthodoxy and piety; Isabella developed this to the edge of asceticism, and was as harsh and cruel in suppressing heresy as she was kind and gracious in everything else. She was the soul of tenderness to her children, and a pillar of loyalty to her friends. She gave abundantly to churches, monasteries, and hospitals. Her orthodoxy did not deter her from condemning the immorality of some Renaissance popes.22 She excelled in both physical and moral bravery; she withstood, subdued, and disciplined powerful nobles, bore quietly the most desolating bereavements, and faced with contagious courage the hardships and dangers of war. She thought it wise to maintain a queenly dignity in public, and pushed royal display to costly extravagance in robes and gems; in private she dressed simply, ate frugally, and amused her leisure by making delicate embroideries for the churches she loved. She labored conscientiously in the tasks of government, took the initiative in wholesome reforms, administered justice with perhaps undue severity; but she was resolved to raise her realm from lawless disorder to a law-abiding peace. Foreign contemporaries like Paolo Giovio, Guicciardini, and the Chevalier Bayard ranked her among the ablest sovereigns of the age, and likened her to the stately heroines of antiquity. Her subjects worshiped her, while they bore impatiently with the King.

The Castilians could not forgive Ferdinand for being a foreigner—i.e., an Aragonese; and they found many faults in him even while they gloried in his successes as statesman, diplomat, and warrior. They contrasted his cold and reserved temperament with the warm kindliness of the Queen, his calculated indirectness with her straightforward candor, his parsimony with her generosity, his illiberal treatment of his aides with her openhanded rewards for services, his extramarital gallantries with her quiet continence. Probably they did not resent his establishment of the Inquisition, nor his use of their religious feelings as a weapon of war; they applauded the campaign against heresy, the conquest of Granada, the expulsion of unconverted Jews and Moors; they loved most in him what posterity would least admire. We hear of no protest against the severity of his laws—cutting out the tongue for blasphemy, burning alive for sodomy.23 They noted that he could be just, even lenient, when it did not hinder personal advantage or national policy; that he could lead his army dauntlessly and cleverly, though he preferred to match minds in negotiation rather than men in battle; and that his parsimony financed not personal luxuries but expensive undertakings for the aggrandizement of Spain. They must have approved of his abstemious habits, his constancy in adversity, his moderation in prosperity, his discerning choice of aides, his tireless devotion to government, his pursuit of farseen ends with flexible tenacity and cautious means. They forgave his duplicity as a diplomat, his frequent faithlessness to his word; were not all other rulers trying by like methods to cozen him and swindle Spain? “The King of France,” he said grimly, “complains that I have twice deceived him. He lies, the fool; I have deceived him ten times, and more.” 24 Machiavelli carefully studied Ferdinand’s career, relished his cunning, praised “his deeds... all great and some extraordinary,” and called him “the foremost king in Christendom.” 25 And Guicciardini wrote: “What a wide difference there was between the sayings and doings of this prince, and how deeply and secretly he laid his measures!”26 Some accounted Ferdinand lucky, but in truth his good fortune lay in careful preparation for events and prompt seizure of opportunities. When the balance was struck between his virtues and his crimes, it appeared that by fair means and foul he had raised Spain from a motley of impotent fragments to a unity and power that in the next generation made her the dictator of Europe.

He co-operated with Isabella in restoring security of life and property in Castile; in reviving the Santa Hermandad, or Holy Brotherhood, as a local militia to maintain order; in ending robbery on the highways and sexual intrigues at the court; in reorganizing the judiciary and codifying the laws; in reclaiming state lands recklessly ceded to favorites by previous kings; and in exacting from the nobles full obedience to the crown; here too, as in France and England, feudal freedom and chaos had to give way to the centralized order of absolute monarchy. The municipal communes likewise surrendered their privileges; the provincial cortes rarely met, and then chiefly to vote funds to the government; a weak-rooted democracy languished and died under an adamantine king. Even the Spanish Church, so precious to los reyes católicosy,* was shorn of some of its wealth and all of its civil jurisdiction; the morals of the clergy were rigorously reformed by Isabella; Pope Sixtus IV was compelled to yield to the government the right to appoint the higher dignitaries of the Church in Spain; and able ecclesiastics like Pedro Gonzáles de Mendoza and Ximenes de Cisneros were promoted to be at once archbishops of Toledo and prime ministers of the state.

Cardinal Ximenes was as positive and powerful a character as the King. Born of a family noble but poor, he was dedicated in childhood to the Church. At the University of Salamanca he earned by the age of twenty the doctoral degrees in both civil and canon law. For some years he served as vicar and administrator for Mendoza in the diocese of Sigüenza. Successful but unhappy, caring little for honors or possessions, he entered the strictest monastic order in Spain—the Observantine Franciscans. Only asceticism delighted him: he slept on the ground or a hard floor, fasted frequently, flogged himself, and wore a hair shirt next to his skin. In 1492 the pious Isabella chose this emaciated cenobite as her chaplain and confessor. He accepted on condition that he might continue to live in his monastery and conform to the rigid Franciscan rule. The order made him its provincial head, and at his bidding submitted to arduous reforms. When Isabella nominated him archbishop of Toledo (1495) he refused to accept, but after six months of resistance he yielded to a papal bull commanding him to serve. He was now nearly sixty, and seems to have sincerely wished to live as a monk. As primate of Spain and chief of the royal council he continued his austerities; under the splendid robes required by his office he wore the coarse Franciscan gown, and under this the hair shirt as before.27 Against the opposition of high ecclesiastics, but supported by the Queen, he applied to all monastic orders the reforms that he had exacted from his own. It was as if St. Francis, shorn of his humility, had suddenly been endowed with the powers and capacities of Bernard and Dominic.

It could not have pleased this somber saint to find two unconverted Jews high in favor at the court. One of Isabella’s most trusted counselors was Abraham Senior; he and Isaac Abrabanel collected the revenue for Ferdinand, and organized the financing of the Granada war. The King and Queen were at this time especially concerned about the Conversos. They had hoped that time would make these converts sincere Christians; Isabella had had a catechism specially prepared for their instruction; yet many of them secretly maintained their ancient faith, and transmitted it to their children. Catholic dislike of the unbaptized Jews subsided for a time, while resentment against the “New Christians” rose. Riots against them broke out in Toledo (1467), Valladolid (1470), Cordova (1472), and Segovia (1474). The religious problem had become also racial; and the young King and Queen pondered means of reducing the disorderly medley and conflict of peoples, languages, and creeds to homogeneous unity and social peace. They thought that no better means were available for these ends than to restore the Inquisition in Spain.

IV. THE METHODS OF THE INQUISITION

We are today so uncertain and diverse in our opinions as to the origin and destiny of the world and man that we have ceased, in most countries, to punish people for differing from us in their religious beliefs. Our present intolerance is rather for those who question our economic or political principles, and we explain our frightened dogmatism on the ground that any doubt thrown upon these cherished assumptions endangers our national solidarity and survival. Until the middle of the seventeenth century Christians, Jews, and Moslems were more acutely concerned with religion than we are today; their theologies were their most prized and confident possessions; and they looked upon those who rejected these creeds as attacking the foundations of social order and the very significance of human life. Each group was hardened by certainty into intolerance, and branded the others as infidels.

The Inquisition developed most readily among persons whose religious tenets had been least affected by education and travel, and whose reason was most subject to custom and imagination. Nearly all medieval Christians, through childhood schooling and surroundings, believed that the Bible had been dictated in every word by God, and that the Son of God had directly established the Christian Church. It seemed to follow, from these premises, that God wished all nations to be Christian, and that the practice of non-Christian—certainly of anti-Christian—religions must be a crass insult to the Deity. Moreover, since any substantial heresy must merit eternal punishment, its prosecutors could believe (and many seem to have sincerely believed) that in snuffing out a heretic they were saving his potential converts, and perhaps himself, from everlasting hell.

Probably Isabella, who lived in the very odor of theologians, shared these views. Ferdinand, being a hardened man of the world, may have doubted some of them; but he was apparently convinced that uniformity of religious belief would make Spain easier to rule, and stronger to strike its enemies. At his request and Isabella’s, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull (November 1, 1478) authorizing them to appoint six priests, holding degrees in theology and canon law, as an inquisitorial board to investigate and punish heresy. The remarkable feature of this bull was its empowerment of the Spanish sovereigns to nominate the inquisitorial personnel, who in earlier forms of the Inquisition had been chosen by the provincial heads of the Dominican or Franciscan orders. Here for three generations, as in Protestant Germany and England in the next century, religion became subject to the state. Technically, however, the inquisitors were only nominated by the sovereigns, and were then appointed by the pope; the authority of the inquisitors derived from this papal sanction; the institution remained ecclesiastical, an organ of the Church, which was an organ of the state. The government was to pay the expenses, and receive the net income, of the Inquisition. The sovereigns kept detailed watch over its operations, and appeal could be made to them from its decisions. Of all Ferdinand’s instruments of rule, this became his favorite. His motives were not primarily financial; he profited from the confiscated property of the condemned, but he refused tempting bribes from rich victims to overrule the inquisitors. The aim was to unify Spain.

The inquisitors were authorized to employ ecclesiastical and secular aides as investigators and executive officers. After 1483 the entire organization was put under a governmental agency, the Concejo de la Suprema y General Inquisicion, usually termed the Suprema. The jurisdiction of the Inquisition extended to all Christians in Spain; it did not touch unconverted Jews or Moors; its terrors were directed at converts suspected of relapsing into Judaism or Mohammedanism, and at Christians charged with heresy; till 1492 the unchristened Jew was safer than the baptized. Priests, monks, and friars claimed exemption from the Inquisition, but their claim was denied; the Jesuits resisted its jurisdiction for half a century, but they too were overcome. The only limit to the power of the Suprema was the authority of the sovereigns; and in later centuries even this was ignored. The Inquisition demanded, and usually received, co-operation from all secular officials.

The Inquisition made its own laws and procedural code. Before setting up its tribunal in a town, it issued to the people, through the parish pulpits, an “Edict of Faith” requiring all who knew of any heresy to reveal it to the inquisitors. Everyone was encouraged to be a delator, to inform against his neighbors, his friends, his relatives. (In the sixteenth century, however, the accusation of near relatives was not allowed.) Informants were promised full secrecy and protection; a solemn anathema—i.e., excommunication and curse—was laid upon all who knew and concealed a heretic. If a baptized Jew still harbored hopes of a Messiah to come; if he kept the dietary laws of the Mosaic code; if he observed the Sabbath as a day of worship and rest, or changed his linen for that day; if he celebrated in any way any Jewish holy day; if he circumcised any of his children, or gave any of them a Hebrew name, or blessed them without making the sign of the cross; if he prayed with motions of the head, or repeated a Biblical psalm without adding a Gloria; if he turned his face to the wall when dying: these and the like were described by the inquisitors as signs of secret heresy, to be reported at once to the tribunal.28 Within a “Term of Grace” any person who felt guilty of heresy might come and confess it; he would be fined or assigned a penance, but would be forgiven, on condition that he should reveal any knowledge he might have of other heretics.

The inquisitors seem to have sifted with care the evidence collected by informers and investigators. When the tribunal was unanimously convinced of a person’s guilt it issued a warrant for his arrest. The accused was kept incommunicado; no one but agents of the Inquisition was allowed to speak with him; no relative might visit him. Usually he was chained.29 He was required to bring his own bed and clothing, and to pay all the expenses of his incarceration and sustenance. If he did not offer sufficient cash for this purpose, enough of his property was sold at auction to meet the costs. The remainder of his goods was sequestrated by Inquisition officers lest it be hidden or disposed of to escape confiscation. In most cases some of it was sold to maintain such of the victim’s family as could not work.

When the arrested person was brought to trial the tribunal, having already judged him guilty, laid upon him the burden of proving his innocence. The trial was secret and private, and the defendant had to swear never to reveal any facts about it in case he should be released. No witnesses were adduced against him, none was named to him; the inquisitors excused this procedure as necessary to protect their informants. The accused was not at first told what charges had been brought against him; he was merely invited to confess his own derelictions from orthodox belief and worship, and to betray all persons whom he suspected of heresy. If his confession satisfied the tribunal, he might receive any punishment short of death. If he refused to confess he was permitted to choose advocates to defend him; meanwhile he was kept in solitary confinement. In many instances he was tortured to elicit a confession. Usually the case was allowed to drag on for months, and the solitary confinement in chains often sufficed to secure any confession desired.

Torture was applied only after a majority of the tribunal had voted for it on the ground that guilt had been made probable, though not certain, by the evidence. Often the torture so decreed was postponed in the hope that dread of it would induce confession. The inquisitors appear to have sincerely believed that torture was a favor to a defendant already accounted guilty, since it might earn him, by confession, a slighter penalty than otherwise; even if he should, after confession, be condemned to death, he could enjoy priestly absolution to save him from hell. However, confession of guilt was not enough, torture might also be applied to compel a confessing defendant to name his associates in heresy or crime. Contradictory witnesses might be tortured to find out which was telling the truth; slaves might be tortured to bring out testimony against their masters. No limits of age could save the victims; girls of thirteen and women of eighty were subjected to the rack; but the rules of the Spanish Inquisition usually forbade the torture of nursing women, or persons with weak hearts, or those accused of minor heresies, such as sharing the widespread opinion that fornication was only a venial sin. Torture was to be kept short of permanently maiming the victim, and was to be stopped whenever the attendant physician so ordered. It was to be administered only in the presence of the inquisitors in charge of the case, and a notary, a recording secretary, and a representative of the local bishop. Methods varied with time and place. The victim might have his hands tied behind his back and be suspended by them; he might be bound into immobility and then have water trickle down his throat till he nearly choked; he might have cords tied around his arms and legs and tightened till they cut through the flesh to the bone. We are told that the tortures used by the Spanish Inquisition were milder than those employed by the earlier papal Inquisition, or by the secular courts of the age.30 The main torture was prolonged imprisonment.

The Inquisition tribunal was not only prosecutor, judge, and jury; it also issued decrees on faith and morals, and established a gradation of penalties. In many cases it was merciful, excusing part of the punishment because of the penitent’s age, ignorance, poverty, intoxication, or generally good reputation. The mildest penalty was a reprimand. More grievous was compulsion to make a public abjuration of heresy—which left even the innocent branded to the end of his days. Usually the convicted penitent was required to attend Mass regularly, wearing the “sanbenito”—a garment marked with a flaming cross. He might be paraded through the streets stripped to the waist and bearing the insignia of his offense. He and his descendants might be barred from public office forever. He might be banished from his city, rarely from Spain. He might be scourged with one or two hundred lashes to “the limit of safety”; this was applied to women as well as men. He might be imprisoned, or condemned to the galleys—which Ferdinand recommended as more useful to the state. He might pay a substantial fine, or have his property confiscated. In several instances dead men were accused of heresy, were tried post-mortem, and were condemned to confiscation, in which case the heirs forfeited his bequests. Informers against dead heretics were offered 30 to 50 per cent of the proceeds. Families fearful of such retroactive judgments sometimes paid “compositions” to the inquisitors as insurance against confiscation of their legacies. Wealth became a peril to its owner, a temptation to informers, inquisitors, and the government. As money flowed into the coffers of the Inquisition its officials became less zealous to preserve the orthodox faith than to acquire gold, and corruption flourished piously.31

The ultimate punishment was burning at the stake. This was reserved for persons who, judged guilty of serious heresy, failed to confess before judgment was pronounced, and for those who, having confessed in time, and having been “reconciled” or forgiven, had relapsed into heresy. The Inquisition itself professed that it never killed, but merely surrendered the condemned person to the secular authorities; however, it knew that the criminal law made burning at the stake mandatory in all convictions for major and impenitent heresy. The official presence of ecclesiastics at the auto-da-fé frankly revealed the responsibility of the Church. The “act of faith” was not merely the burning, it was the whole impressive and terrible ceremony of sentence and execution. Its purpose was not only to terrify potential offenders, but to edify the people as with a foretaste of the Last Judgment.

At first the procedure was simple: those condemned to death were marched to the public plaza, they were bound in tiers on a pyre, the inquisitors sat in state on a platform facing it, a last appeal for confessions was made, the sentences were read, the fires were lit, the agony was consummated. But as burnings became more frequent and suffered some loss in their psychological power, the ceremony was made more complex and awesome, and was staged with all the care and cost of a major theatrical performance. When possible it was timed to celebrate the accession, marriage, or visit of a Spanish king, queen, or prince. Municipal and state officials, Inquisition personnel, local priests and monks, were invited—in effect required—to attend. On the eve of the execution these dignitaries joined in a somber procession through the main streets of the city to deposit the green cross of the Inquisition upon the altar of the cathedral or principal church. A final effort was made to secure confessions from the condemned; many then yielded, and had their sentences commuted to imprisonment for a term or for life. On the following morning the prisoners were led through dense crowds to a city square: impostors, blasphemers, bigamists, heretics, relapsed converts; in later days, Protestants; sometimes the procession included effigies of absent condemnees, or boxes carrying the bones of persons condemned after death. In the square, on one or several elevated stages, sat the inquisitors, the secular and monastic clergy, and the officials of town and state; now and then the King himself presided. A sermon was preached, after which all present were commanded to recite an oath of obedience to the Holy Office of the Inquisition, and a pledge to denounce and prosecute heresy in all its forms and everywhere Then, one by one, the prisoners were led before the tribunal, and their sentences were read. We must not imagine any brave defiances; probably, at this stage, every prisoner was near to spiritual exhaustion and physical collapse. Even now he might save his life by confession; in that case the Inquisition usually contented itself with scourging him, confiscating his goods, and imprisoning him for life. If the confession was withheld till after sentence had been pronounced, the prisoner earned the mercy of being strangled before being burned; and as such last-minute confessions were frequent, burning alive was relatively rare. Those who were judged guilty of major heresy, but denied it to the end, were (till 1725) refused the last sacraments of the Church, and were, by the intention of the Inquisition, abandoned to everlasting hell. The “reconciled” were now taken back to prison; the impenitent were “relaxed” to the secular arm, with a pious caution that no blood should be shed. These were led out from the city between throngs that had gathered from leagues around for this holiday spectacle. Arrived at the place prepared for execution, the confessed were strangled, then burned; the recalcitrant were burned alive. The fires were fed till nothing remained of the dead but ashes, which were scattered over fields and streams. The priests and spectators returned to their altars and their homes, convinced that a propitiatory offering had been made to a God insulted by heresy. Human sacrifice had been restored.

V. PROGRESS OF THE INQUISITION: 1480–1516

The first inquisitors were appointed by Ferdinand and Isabella in September 1480, for the district of Seville. Many Sevillian Conversos fled to the countryside, and sought sanctuary with feudal lords. These were inclined to protect them, but the inquisitors threatened the barons with excommunication and confiscation, and the refugees were surrendered. In the city itself some Conversos planned armed resistance; the plot was betrayed; the implicated persons were arrested; soon the dungeons were full. Trials followed with angry haste, and the first auto-da-fé of the Spanish Inquisition was celebrated on February 6, 1481, with the burning of six men and women. By November 4 of that year 298 had been burned; seventy-nine had been imprisoned for life.

In 1483, at the nomination and request of Ferdinand and Isabella, Pope Sixtus IV appointed a Dominican friar, Tomás de Torquemada, inquisitorgeneral for all of Spain. He was a sincere and incorruptible fanatic, scorning luxury, working feverishly, rejoicing in his opportunity to serve Christ by hounding heresy. He reproved inquisitors for lenience, reversed many acquittals, and demanded that the rabbis of Toledo, on pain of death, should inform on all Judaizing Conversos. Pope Alexander VI, who had at first praised his devotion to his tasks, became alarmed at his severity, and ordered him (1494) to share his powers with two other “inquisitors general.” Torquemada overrode these colleagues, maintained a resolute leadership, and made the Inquisition an imperium in imperio, rivaling the power of the sovereigns. Under his prodding the Inquisition at Ciudad Real in two years (1483–84) burned fifty-two persons, confiscated the property of 220 fugitives, and punished 183 penitents. Transferring their headquarters to Toledo, the inquisitors within a year arrested 750 baptized Jews, confiscated a fifth of their goods, and sentenced them to march in penitential processions on six Fridays, flogging themselves with hempen cords. Two further autos-da-fé in that year (1486) at Toledo disciplined 1,650 penitents. Like labors were performed in Valladolid, Guadalupe, and other cities of Castile.

Aragon resisted the Inquisition with forlorn courage. At Teruel the magistrates closed the gates in the face of the inquisitors. These laid an interdict upon the city; Ferdinand stopped the municipal salaries, and sent an army to enforce obedience; the environing peasants, always hostile to the city, ran to the support of the Inquisition, which promised them release from all rents and debts due to persons convicted of heresy. Teruel yielded, and Ferdinand authorized the inquisitors to banish anyone whom they suspected of having aided the opposition. In Saragossa many “Old Christians” joined the “New Christians” in protesting against the entry of the Inquisition; when, nevertheless, it set up its tribunal there, some Conversos assassinated an inquisitor (1485). It was a mortal blunder, for the shocked citizens thronged the streets crying “Burn the Conversos!” The archbishop calmed the mob with a promise of speedy justice. Nearly all the conspirators were caught and executed; one leaped to his death from the tower in which he was confined; another broke a glass lamp, swallowed the fragments, and was found dead in his cell. In Valencia the Cortes refused to allow the inquisitors to function; Ferdinand ordered his agents to arrest all obstructors; Valencia gave way. In support of the Inquisition the King violated one after another of the traditional liberties of Aragon; the combination of Church and monarchy, of excommunications and royal armies, proved too strong for any single city or province to resist. In 1488 there were 983 condemnations for heresy in Valencia alone, and a hundred men were burned.

How did the popes view this use of the Inquisition as an instrument of the state? Doubtless resenting such secular control, moved, presumably, by humane sentiment, and not insensitive to the heavy fees paid for dispensations from Inquisition sentences, several popes tried to check its excesses, and gave occasional protection to its victims. In 1482 Sixtus IV issued a bull which, if implemented, would have ended the Inquisition in Aragon. He complained that the inquisitors were showing more lust for gold than zeal for religion; that they had imprisoned, tortured, and burned faithful Christians on the dubious evidence of enemies or slaves. He commanded that in future no inquisitor should act without the presence and concurrence of some representative of the local bishop; that the names and allegations of the accusers should be made known to the accused; that the prisoners of the Inquisition should be lodged only in episcopal jails; that those complaining of injustice should be allowed to appeal to the Holy See, and all further action in the case should be suspended until judgment should be rendered on the appeal; that all persons convicted of heresy should receive absolution if they confessed and repented, and thereafter should be free from prosecution or molestation on that charge. All past proceedings contrary to these provisions were declared null and void, and all future violators of them were to incur excommunication. It was an enlightened decree, and its thoroughness suggests its sincerity. Yet we must note that it was confined to Aragon, whose Conversos had paid for it liberally.32 When Ferdinand defied it, arrested the agent who had procured it, and bade the inquisitors go on as before, Sixtus took no further action in the matter, except that five months later he suspended the operation of the bull.33

The desperate Conversos poured money into Rome, appealing for dispensations and absolutions from the summons or sentences of the Inquisition. The money was accepted, the dispensations were given, the Spanish inquisitors, protected by Ferdinand, ignored them; and the popes, needing the friendship of Ferdinand and the annates of Spain, did not insist. Pardons were paid for, issued, and then revoked. Occasionally the popes asserted their authority, citing inquisitors to Rome to answer charges of misconduct. Alexander VI tried to moderate the severity of the tribunal. Julius II ordered the trial of the inquisitor Lucero for malfeasance, and excommunicated the inquisitors of Toledo. The gentle and scholarly Leo, however, denounced as a reprehensible heresy the notion that a heretic should not be burned.34

How did the people of Spain react to the Inquisition? The upper classes and the educated minority faintly opposed it; the Christian populace usually approved it.35 The crowds that gathered at the autos-da-fé showed little sympathy, often active hostility, to the victims; in some places they tried to kill them lest confession should let them escape the pyre. Christians flocked to buy at auction the confiscated goods of the condemned.

How numerous were the victims? Llorente* estimated them, from 1480 to 1488, at 8,800 burned, 96,494 punished; from 1480 to 1808, at 31,912 burned, 291,450 heavily penanced. These figures were mostly guesses, and are now generally rejected by Protestant historians as extreme exaggerations.36 A Catholic historian reckons 2,000 burnings between 1480 and 1504, and 2,000 more to 1758.37 Isabella’s secretary, Hernando de Pulgar, calculated the burnings at 2,000 before 1490. Zurita, a secretary of the Inquisition, boasted that it had burned 4,000 in Seville alone. There were victims, of course, in most Spanish cities, even in Spanish dependencies like the Baleares, Sardinia, Sicily, the Netherlands, America. The rate of burnings diminished after 1500. But no statistics can convey the terror in which the Spanish mind lived in those days and nights. Aden and women, even in the secrecy of their families, had to watch every word they uttered, lest some stray criticism should lead them to an Inquisition jail. It was a mental oppression unparalleled in history.

Did the Inquisition succeed? Yes, in attaining its declared purpose—to rid Spain of open heresy. The idea that the persecution of beliefs is always ineffective is a delusion; it crushed the Albigensians and Huguenots in France, the Catholics in Elizabethan England, the Christians in Japan. It stamped out in the sixteenth century the small groups that favored Protestantism in Spain. On the other hand, it probably strengthened Protestantism in Germany, Scandinavia, and England by arousing in their peoples a vivid fear of what might happen to them if Catholicism were restored.

It is difficult to say what share the Inquisition had in ending the brilliant period of Spanish history from Columbus to Velásquez (1492–1660). The peak of that epoch came with Cervantes (1547–1616) and Lope de Vega (1562–1635), after the Inquisition had flourished in Spain for a hundred years. The Inquisition was an effect, as well as a cause, of the intense and exclusive Catholicism of the Spanish people; and that religious mood had grown during centuries of struggle against “infidel” Moors. The exhaustion of Spain by the wars of Charles V and Philip II, and the weakening of the Spanish economy by the victories of Britain on the sea and the mercantile policies of the Spanish government, may have had more to do with the decline of Spain than the terrors of the Inquisition. The executions for witchcraft, in northern Europe and New England, showed in Protestant peoples a spirit akin to that of the Spanish Inquisition—which, strange to say, sensibly treated witchcraft as a delusion to be pitied and cured rather than punished. Both the Inquisition and the witch-burning were expressions of an age afflicted with homicidal certainty in theology, as the patriotic massacres of our era may be due in part to homicidal certainty in ethnic or political theory. We must try to understand such movements in terms of their time, but they seem to us now the most unforgivable of historic crimes. A supreme and unchallengeable faith is a deadly enemy to the human mind.

VI. IN EXITU ISRAEL38

The Inquisition was intended to frighten all Christians, new or old, into at least external orthodoxy, in the hope that heresy would be blighted in the bud, and that the second or third generation of baptized Jews would forget the Judaism of their ancestors. There was no intent to let baptized Jews leave Spain; when they tried to emigrate, Ferdinand and the Inquisition forbade it. But what of the unbaptized Jews? Some 235,000 of them remained in Christian Spain. How could the religious unity of the nation be effected if these were allowed to practice and profess their faith? Torquemada thought it impossible, and recommended their compulsory conversion or their banishment.

Ferdinand hesitated. He knew the economic value of Hebrew ability in commerce and finance. But he was told that the Jews taunted the Conversos and sought to win them back to Judaism, if only secretly. His physician, Ribas Altas, a baptized Jew, was accused of wearing on a pendant from his neck a golden ball containing a representation of himself in the act of desecrating a crucifix; the charge seems incredible, but the physician was burned (1488).39 Letters were forged in which a Jewish leader in Constantinople advised the head of the Jewish community in Spain to rob and poison Christians as often as possible.40 A Converso was arrested on the charge of having a consecrated wafer in his knapsack; he was tortured again and again until he signed a statement that six Conversos and six Jews had killed a Christian child to use its heart in a magic ceremony designed to cause the death of all Christians and the total destruction of Christianity. The confessions of the tortured man contradicted one another, and no child was reported missing; however, four Jews were burned, two of them after having their flesh torn away with red-hot pincers.41 These and similar accusations may have influenced Ferdinand; in any case they prepared public opinion for the expulsion of all unbaptized Jews from Spain. When Granada surrendered (November 5, 1491), and the industrial and commercial activities of the Moors accrued to Christian Spain, the economic contribution of the unconverted Jews no longer seemed vital. Meanwhile popular fanaticism, inflamed by autos-da-fé and the preaching of the friars, was making social peace impossible unless the government either protected or expelled the Jews.

On March 30, 1492—so crowded a year in Spanish history—Ferdinand and Isabella signed the edict of exile. All unbaptized Jews, of whatever age or condition, were to leave Spain by July 31, and were never to return, on penalty of death. In this brief period they might dispose of their property at whatever price they could obtain. They might take with them movable goods and bills of exchange, but no currency, silver, or gold. Abraham Senior and Isaac Abrabanel offered the sovereigns a large sum to withdraw the edict, but Ferdinand and Isabella refused. No royal accusation was made against the Jews, except their tendency to lure Conversos back to Judaism. A supplementary edict required that taxes to the end of the year should be paid on all Jewish property and sales. Debts due from Christians or Moors were to be collected only at maturity, through such agents as the banished creditors might find, or these claims could be sold at a discount to Christian purchasers. In this enforced precipitancy the property of the Jews passed into Christian hands at a small fraction of its value. A house was sold for an ass, a vineyard for a piece of cloth. Some Jews, in despair, burned down their homes (to collect insurance?); others gave them to the municipality. Synagogues were appropriated by Christians and transformed into churches. Jewish cemeteries were turned into pasturage. In a few months the largest part of the riches of the Spanish Jews, accumulated through centuries, melted away. Approximately 50,000 Jews accepted conversion, and were permitted to remain; over 100,000 left Spain in a prolonged and melancholy exodus.

Before departing they married all their children who were over twelve years of age. The young helped the old, the rich succored the poor. The pilgrimage moved on horses or asses, in carts or on foot. At every turn good Christians—clergy and laity—appealed to the exiles to submit to baptism. The rabbis countered by assuring their followers that God would lead them to the promised land by opening a passage through the sea, as He had done for their fathers of old.42 The emigrants who gathered in Cádiz waited hopefully for the waters to part and let them march dryshod to Africa. Disillusioned, they paid high prices for transport by ship. Storms scattered their fleet of twenty-five vessels; sixteen of these were driven back to Spain, where many desperate Jews accepted baptism as no worse than seasickness. Fifty Jews, shipwrecked near Seville, were imprisoned for two years and then sold as slaves.43 The thousands who sailed from Gibraltar, Málaga, Valencia, or Barcelona found that in all Christendom only Italy was willing to receive them with humanity.

The most convenient goal of the pilgrims was Portugal. A large population of Jews already existed there, and some had risen to wealth and political position under friendly kings. But John II was frightened by the number of Spanish Jews—perhaps 80,000—who poured in. He granted them a stay of eight months, after which they were to leave. Pestilence broke out among them, and spread to the Christians, who demanded their immediate expulsion. John facilitated the departure of the immigrant Jews by providing ships at low cost; but those who confided themselves to these vessels were subjected to robbery and rape; many were cast upon desolate shores and left to die of starvation or to be captured and enslaved by Moors.44 One shipload of 250 Jews, being refused at port after port because pestilence still raged among them, wandered at sea for four months. Biscayan pirates seized one vessel, pillaged the passengers, then drove the ships into Málaga, where the priests and magistrates gave the Jews a choice of baptism or starvation.

After fifty of them had died, the authorities provided the survivors with bread and water, and bade them sail for Africa.45

When the eight months of grace had expired, John II sold into slavery those Jewish immigrants who still remained in Portugal. Children under fifteen were taken from their parents, and were sent to the St. Thomas Islands to be reared as Christians. As no appeals could move the executors of the decree, some mothers drowned themselves and their children rather than suffer their separation.46 John’s successor, Manuel, gave the Jews a breathing spell: he freed those whom John had enslaved, forbade the preachers to incite the populace against the Jews, and ordered his courts to dismiss as malicious tales all allegations of the murder of Christian children by Jews.47 But meanwhile Manuel courted Isabella, daughter and heiress of Isabella and Ferdinand, and dreamed of uniting both thrones under one bed. The Catholic sovereigns agreed, on condition that Manuel expel from Portugal all unbaptized Jews, native or immigrant. Loving honors above honor, Manuel consented, and ordered all Jews and Moors in his realm to accept baptism or banishment (1496). Finding that only a few preferred baptism, and loath to disrupt the trades and crafts in which the Jews excelled, he ordered all Jewish children under fifteen to be separated from their parents and forcibly baptized. The Catholic clergy opposed this measure, but it was carried out. “I have seen,” reported a bishop, “many children dragged to the font by the hair.”48 Some Jews killed their children, and then themselves, in protest. Manuel grew ferocious; he hindered the departure of Jews, then ordered them to be baptized by force. They were dragged to the churches by the beards of the men and the hair of the women, and many killed themselves on the way. The Portuguese Conversos sent a dispatch to Pope Alexander VI begging his intercession; his reply is unknown; it was probably favorable, for Manuel now (May 1497) granted to all forcibly baptized Jews a moratorium of twenty years, during which they were not to be brought before any tribunal on a charge of adhering to Judaism. But the Christians of Portugal resented the economic competition of the Jews, baptized or not; when one Jew questioned a miracle alleged to have occurred in a Lisbon church, the populace tore him to pieces (1506); for three days massacre ran free; 2,000 Jews were killed; hundreds of them were buried alive. Catholic prelates denounced the outrage, and two Dominican friars who had incited the riot were put to death.49 Otherwise, for a generation, there was almost peace.

From Spain the terrible exodus was complete. But religious unity was not yet achieved: the Moors remained. Granada had been taken, but its Mohammedan population had been guaranteed religious liberty. Archbishop Hernando de Talavera, commissioned to govern Granada, scrupulously observed this compact, and sought to make converts by kindness and justice. Ximenes did not approve such Christianity. He persuaded the Queen that faith need not be kept with infidels, and induced her to decree (1499) that the Moors must become Christians or leave Spain. Going himself to Granada, he overruled Talavera, closed the mosques, made public bonfires of all the Arabic books and manuscripts he could lay his hands on,50 and supervised wholesale compulsory christenings. The Moors washed the holy water from their children as soon as they were out of the priests’ sight. Revolts broke out in the city and the province; they were crushed. By a royal edict of February 12, 1502, all Moslems in Castile and León were given till April 30 to choose between Christianity and exile. The Moors protested that when their forefathers had ruled much of Spain they had given religious liberty, with rare exceptions, to the Christians under their sway,51 but the sovereigns were not moved. Boys under fourteen and girls under twelve were forbidden to leave Spain with their parents, and feudal barons were allowed to retain their Moorish slaves provided these were kept in fetters.52 Thousands departed; the rest accepted baptism more philosophically than the Jews; and as “Moriscos” they took the place of the baptized Jews in suffering the penalties of the Inquisition for relapses into their former faith. During the sixteenth century 3,000,000 superficially converted Moslems left Spain.53 Cardinal Richelieu called the edict of 1502 “the most barbarous in history”;54 but the friar Bleda thought it “the most glorious event in Spain since the time of the Apostles. Now,” he added, “religious unity is secured, and an era of prosperity is certainly about to dawn.”55

Spain lost an incalculable treasure by the exodus of Jewish and Moslem merchants, craftsmen, scholars, physicians, and scientists, and the nations that received them benefited economically and intellectually. Knowing henceforth only one religion, the Spanish people submitted completely to their clergy, and surrendered all right to think except within the limits of the traditional faith. For good or ill, Spain chose to remain medieval, while Europe, by the commercial, typographical, intellectual, and Protestant revolutions, rushed into modernity.

VII. SPANISH ART

Spanish architecture, persistently Gothic, powerfully expressed this enduring medieval mood. The people did not grudge the maravedis that helped royal and noble conscience money, or religious policy, to build immense cathedrals, and to lavish costly ornaments and awesome sculpture and painting upon their favorite saints and the passionately worshiped Mother of God. Barcelona’s cathedral rose slowly between 1298 and 1448: amid the chaos of minor streets it lifts its towering columns, an undistinguished portal, a majestic nave, while its many-fountained cloisters still give refuge from the strife of the day. Valencia, Toledo, Burgos, Lérida, Tarragona, Saragossa, León, extended or embellished their preexisting temples, while new ones rose at Huesca and Pamplona—whose cloisters of white marble, elegantly carved, are as fair as the Alhambra’s patios. In 1401 the cathedral chapter at Seville resolved to erect a church “so great and so beautiful that those who in coming ages shall look upon it will think us lunatics for attempting it.”56 The architects removed the decayed mosque that stood on the chosen site, but kept its foundations, its ground plan, and its noble Giralda minaret. All through the fifteenth century stone rose upon stone until Seville had raised the largest Gothic edifice in the world,* so that, said Théophile Gautier, “Notre Dame de Paris might walk erect in the nave.”57 However, Notre Dame is perfect; Seville Cathedral is vast. Sixty-seven sculptors and thirty-eight painters from Murillo to Goya toiled to adorn this mammoth cave of the gods.

About 1410 the architect Guillermo Boffi proposed to the cathedral chapter of Gerona to remove the columns and arches that divided the interior into nave and aisles, and to unite the walls by a single vault seventy-three feet wide. It was done, and the nave of Gerona Cathedral has now the broadest Gothic vault in Christendom. It was a triumph for engineering, a defeat for art. Shrines not so stupendous rose in the fifteenth century at Perpignan, Manresa, Astorga, and Valladolid. Segovia crowned itself with a fortresslike cathedral in 1472; Sigüenza finished its famous cloisters in 1507; Salamanca began its new fane in 1513. In almost every major city of Spain, barring Madrid, a cathedral rises in overwhelming majesty of external mass, with interiors darkly deprecating the sun and terrifying the soul into piety, yet brilliant with the high colors of Spanish painting, and painted statuary, and the gleam of jewelry, silver, and gold. These are the homes of the Spanish spirit, fearfully subdued and fiercely proud.

Nevertheless the kings, nobles, and cities found funds for costly palaces. Peter the Cruel, Ferdinand and Isabella, and Charles V remodeled the Alcazar that a Moorish architect had designed at Seville in 1181; most of the reconstruction was done by Moors from Granada, so that the edifice is a weak sister of the Alhambra. In like Saracenic style Don Pedro Enriquez built for the dukes of Alcalá at Seville (1500 f.) a lordly palace, the Casa de Pilatos, supposedly duplicating the house from whose portico Pilate was believed to have surrendered Christ to crucifixion. Valencia’s Audiencia, or Hall of Audience (1500), provided for the local Cortes a Salon Dorado whose splendor challenged the Sala del Maggior Consiglio in the Palace of the Doges at Venice.

Sculpture was still a servant of architecture and the faith, crowding Spanish churches with Virgins in marble, metal, stone, or wood; here piety was petrified into forms of religious intensity or ascetic severity, enhanced with color, and made more awe-inspiring by the profound gloom of the naves. Retables—carved and painted screens raised behind the altar table—were a special pride of Spanish art; great sums, usually bequeathed in terror of death, were spent to gather and maintain the most skillful workers—designers, carvers, doradores who gilded or damascened the surfaces, estofadores who painted the garments and ornaments, encarnadores who colored the parts representing flesh; all labored together or by turns on the propitiatory shrine. Behind the central altar of Seville Cathedral a retable of forty-five compartments (1483–1519) pictured beloved legends in painted or gilded statuary of late Gothic style; while another in the Chapel of St. James in Toledo Cathedral displayed in gilt larchwood and stern realism the career of Spain’s most honored saint.

Princes and prelates might be represented in sculpture, but only on their tombs, which were placed in churches or monasteries conceived as the antechambers of paradise. So Doña Mencia Enríquez, Duchess of Albuquerque, was buried in a finely chiseled sepulcher now in the Hispanic Society Museum in New York; and Pablo Ortiz carved for the cathedral of Toledo sumptuous sarcophagi for Don Alvaro de Luna and his wife. In the Carthusian monastery of Miraflores, near Burgos, Gil de Siloé designed in Italian style a superb mausoleum for the parents and brothers of the Queen. Isabella was so pleased with these famous Sepulcros de los Reyes that when her favorite page, Juan de Padilla (so recklessly brave that she called him mi loco, “my fool”) was shot through the head at the siege of Granada, she commissioned De Siloé to carve a tomb of royal quality to harbor his corpse; and Gil again rivaled the best Italian sculpture of his time.

No art is more distinctive than the Spanish, yet none has more devoutly submitted to foreign influence. First, of course, to the Moorish influence, long domiciled in the Peninsula, but having its roots in Mesopotamia and Persia, and bringing into the Iberian style a delicacy of workmanship, and a passion for ornament, hardly equaled in any other Christian land. In the minor arts, where decoration was most in place, Spain imitated, and never surpassed, her Saracenic preceptors. Pottery was left almost entirely to the Mudejares, whose lustered ware was rivaled only by the Chinese, and whose colored tiles—above all, the blue azulejos—glorified the floors, altars, fountains, walls, and roofs of Christian Spain. The same Moorish skill made Spanish textiles—velvets, silks, and lace—the finest in Christendom. It appears again in Spanish leather, in the arabesques of the metal screens, in the religious monstrances, in the wood carving of the retables, choir stalls, and vaults. Later influences seeped in from Byzantine painting, then from France, Burgundy, the Netherlands, Germany From the Dutch and the Germans, Spanish sculpture and painting derived their startling realism-emaciated Virgins graphically old enough to be the mother of the Crucified, despite Michelangelo’s dictum about virginity embalming youth. In the sixteenth century all these influences receded before the continent-wide triumph of the Italian style.

Spanish painting followed a similar evolution, but developed tardily, perhaps because the Moors gave here no help or lead. The Catalan frescoes of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries are inferior in design to the Altamira cave paintings of prehistoric Spain. Yet by 1300 painting had become a craze in the Peninsula; a thousand artists painted immense murals, huge altarpieces; some of these, from as early as 1345, have survived much longer than they deserved. In 1428 Jan van Eyck visited Spain, importing a powerful Flemish influence. Three years later the King of Aragon sent Luis Dalmau to study in Bruges; returning, Luis painted an all-too-Flemish Virgin of the Councilors. Thereafter Spanish painters, though still preferring tempera, more and more mixed their colors in oil.

The age of the Primitives in Spanish painting culminated in Bartolomé Bormejo (d. 1498). As early as 1447 he made a name for himself with the Santo Domingo that hangs in the Prado. The Santa Engracia bought by the Gardner Museum of Boston, and the gleaming St. Michael of Lady Ludlow’s collection are almost worthy of Raphael, who came a generation later. But best of all is the Pietà (1490) in the Barcelona Cathedral: a bald, bespectacled Jerome; a dark and Spanish Mary holding her limp, haggard, lifeless Son; in the background the towers of Jerusalem under a lowering sky; and on the right a ruthless portrait of the donor, Canon Despla, uncombed and unshaved, resembling a bandit penitent but condemned, and suggesting Bermejo’s “dour conception of humanity.”58 Here Italian grace is transformed into Spanish force, and realism celebrates its triumph in Spanish art.