CHAPTER II

England: Wyclif, Chaucer, and the Great Revolt

1308–1400

I. THE GOVERNMENT

ON February 2 5,1308, Edward II, sixth king of the house of Plantagenet, in a solemn coronation before the hierarchy and nobility assembled in Westminster Abbey, took the oath that England proudly requires of all her sovereigns:

Archbishop of Canterbury: Sire, will you grant and keep, and by your oath confirm, to the people of England, the laws and customs to them granted by the ancient kings of England, your righteous and godly predecessors, and especially the laws, customs, and privileges granted to the clergy and people by the glorious King St. Edward your predecessor?

King: I grant them and promise.

Archbishop: Sire, will you keep toward God and Holy Church, and to clergy and people, peace and accord in God, entirely, after your power?

King: I will keep them.

Archbishop: Sire, will you cause to be done, in all your judgments, equal and right justice and discretion, in mercy and truth, to your power?

King: I will do so.

Archbishop: Sire, do you grant to hold and to keep the laws and righteous customs which the community of your realm shall have chosen, and will you defend and strengthen them to the honor of God, to the utmost of your power?

King: I grant and promise.1

Having so sworn, and being duly anointed and consecrated with holy oils, Edward II consigned the government to corrupt and incompetent hands, and devoted himself to a life of frivolity with Piers Gaveston, his Ganymede. The barons rebelled, caught and slew Gaveston (1312), and subordinated Edward and England to their feudal oligarchy. Returning in disgrace from his defeat by the Scots at Bannockburn (1314), Edward solaced himself with a new love, Hugh le Despenser III. A conspiracy of his neglected wife, Isabella of France, and her paramour, Roger de Mortimer, deposed him (1326); he was murdered in Berkeley Castle by Mortimer’s agent (1327); and his fifteen-year-old son was crowned as Edward III.

The noblest event of this age in English history was the establishment (1322) of a precedent that required the consent of a national assembly for the validity of any law. It had long been the custom of English monarchs, in their need, to summon a “King’s Council” of prominent nobles and prelates. In 1295 Edward I, warring at once with France, Scotland, and Wales, and most earnestly desirous of cash and men, instructed “every city, borough, and leading town” to send two burgesses (enfranchised citizens), and every shire or county to send two knights (minor nobles), to a national assembly that would form, with the King’s Council, the first English Parliament. The towns had money, which their delegates might be persuaded to vote to the king; the shires had yeomen (freeholders), who would make sturdy archers and pikemen; the time had come to build these forces into the structure of British government. There was no pretense at full democracy. Though the towns were—or by 1400 would be—free from feudal overlordship, the urban vote was confined to a small minority of propertied men. The nobles and clergy remained the rulers of England: they owned most of the land, employed most of the population as their tenants or serfs, and organized and directed the armed forces of the nation.

The Parliament (as it came to be called under Edward III) met in the royal palace at Westminster, across from the historic Abbey. The archbishops of Canterbury and York, the eighteen bishops, and the major abbots sat at the right of the king; half a hundred dukes, marquises, earls, viscounts, and barons sat on his left; the Prince of Wales and the King’s Council gathered near the throne; and the judges of the realm, seated on woolsacks to remind them how vital the wool trade was to England, attended to advise on points of law. At the opening of the session the burgesses and knights-later known as the Commons—stood uncovered below a bar that separated them from the prelates and lords; now for the first time (1295) the national assembly had an Upper and a Lower House. The united houses received from the king or his chancellor a pronunciatio (the later “speech from the throne”) explaining the subjects to be discussed and the appropriations desired. Then the Commons withdrew to meet in another hall—usually the chapter house of Westminster Abbey. There they debated the royal proposals. These deliberations ended, they delegated a “speaker” to report the result to the Upper House, and to present their petitions to the king. At the close of the sessions the two houses came together again to receive the reply of the sovereign, and to be dismissed by him. Only the king had the authority to summon or dissolve the Parliament,

Both houses claimed, and normally enjoyed, freedom of debate. In many cases they spoke or wrote their minds vigorously to the ruler; on several occasions, however, he had a too audacious critic jailed. In theory the powers of Parliament extended to legislation; in practice most of the statutes passed had been presented as bills by the royal ministers; but the houses often submitted recommendations and grievances, and delayed the voting of funds till some satisfaction was obtained. The only weapon of the Commons was this “power of the purse”; but as the cost of administration and the wealth of the towns grew, the power of the Commons rose. The monarchy was neither absolute nor constitutional. The king could not openly and directly change a law made by Parliament or enact a new one; but through most of the year he ruled without a Parliament to check him, and issued executive decrees that affected every department of English life. He succeeded to the throne not by election but by pedigree. His person was accounted religiously sacred; obedience and loyalty to him were inculcated with all the force of religion, custom, law, education, and ceremonious oath. If this might not suffice, the law of treason directed that a captured rebel against the state should be dragged through the streets to the gallows, should have his entrails torn out and burned before his face, and should then be hanged.2

In 1330 Edward III, eighteen, took over the government, and began one of the most eventful reigns in the history of England. “His body was comely,” says a contemporary chronicler, “and his face was like that of a god”;3 till venery weakened him he was every inch a king. He almost ignored domestic politics, being a warrior rather than a statesman; he yielded powers to Parliament amiably so long as it financed his campaigns. Through his long rule he bled France white in the effort to add her to his crown. Yet there was chivalry in him, frequent gallantry, and such treatment of the captured French King John as would have graced King Arthur’s court. After building the Round Tower of Windsor with the forced labor of 722 men, he held a Round Table there with his favorite knights; and he presided over many a chivalric joust. Froissart tells a story, unverified, of how Edward tried to seduce the lovely Countess of Salisbury, was courteously repulsed, and staged a tournament in order to feast his soul on her beauty again.4 A charming legend tells how the Countess dropped a garter while dancing at court, and how the King snatched it up from the floor, and said, Honi soit qui mal y pense—” Shame to him who evil thinks of it.” The phrase became the motto of that Order of the Garter which Edward founded toward 1349.

Alice Perrers proved less difficult than the Countess; though married, she yielded herself to the avid monarch, took large grants of land in return, and acquired such influence over him that Parliament registered a protest. Queen Philippa (says her fond pensioner Froissart) bore all this patiently, forgave him, and, on her deathbed, asked him only to fulfill her pledges to charity, and, “when it shall please God to call you hence, to choose no other sepulcher, but to lie by my side.”5 He promised “with tears in his eyes,” returned to Alice, and gave her the Queen’s jewelry.6

He waged his wars with energy, courage, and skill. War was then rated the highest and noblest work of kings; unwarlike rulers were despised, and three such in England’s history were deposed. If one may venture a slight anachronism, a natural death was a disgrace that no man could survive. Every member of the European nobility was trained to war; he could advance in possessions and power only by proficiency and bravery in arms. The people suffered from the wars but, till this reign, had rarely fought in them; their children lost the memory of the suffering, heard old knightly tales of glory, and crowned with their choicest laurels those of their kings that shed the most alien blood.

When Edward proposed to conquer France, few of his councilors dared to advise conciliation. Only when the war had dragged on through a generation, and had burdened even the rich with taxes, did the national conscience raise a cry for peace. Discontent neared revolution when Edward’s campaigns, passing from victory to failure, threatened the collapse of the nation’s economy. Till 1370 Edward had profited in war and diplomacy from the wise and loyal service of Sir John Chandos. When this hero died, his place at the head of the King’s Council was taken by Edward’s son, the Duke of Lancaster, named John of Gaunt from the Gant or Ghent where he had been born. John carelessly turned the government over to political buccaneers who fattened their purses at the public expense. Demands for reform were raised in Parliament, and men of good will prayed for the nation’s happy recovery through the King’s speedy death. Another of his sons, the Black Prince—named probably from the color of his armor—might have brought new vigor to the government, but in 1376 he passed away while the old King lingered on. The “Good Parliament” of that year enacted some reform measures, put two malfeasants in jail, ordered Alice Perrers from court, and bound the bishops to excommunicate her if she returned. After the Parliament dispersed, Edward, ignoring its decrees, restored John of Gaunt to power and Alice to the royal bed; and no bishop dared reprove her. At last the obstinate monarch consented to die (1377). A son of the Black Prince succeeded to the throne as Richard II, a lad of eleven years, amid economic and political chaos, and religious revolt.

II. JOHN WYCLIF; 1320–84

What were the conditions that led England, in the fourteenth century, to rehearse the Reformation?

Probably the morals of the clergy played only a secondary role in the drama. The higher clergy had reconciled itself to celibacy; we hear of a Bishop Burnell who had five sons,7 but presumably he was exceptional. Wyclif, Langland, Gower, and Chaucer agreed in noting a predilection, among monks and friars, for good food and bad women. But the Britons would hardly have created a national furore over such deviations, already hallowed by time, or about nuns who came to services with their dogs on leash and their pet birds on their arms,8 or monks who raced through their incoherent prayers. (The humorous English assigned to Satan a special assistant to collect all syllables dropped by “graspers, leapers, gallopers, mumblers, fore-skippers, and fore-runners” in such syncopated devotions, and allotted the sinner a year in hell for each ignored or trampled syllable.9)

What gnawed at the purse nerves of laity and government was the expanding and migratory wealth of the English Church. The clergy on several occasions contributed a tenth of their income to the state, but they insisted that no tax could be laid upon them without the consent of their convocations. Besides being represented in the Upper House of Parliament by their bishops and abbots, they gathered, directly or by proctors, in convocations under the archbishops of Canterbury and York, and determined there all matters dealing with religion or the clergy. It was usually from the ranks of the clergy, as the best-educated class in England, that the king chose the highest officials of the state. Suits of laymen against clergymen, touching Church property, were subject to the king’s courts, but the bishops’ courts had sole jurisdiction over tonsured offenders. In many towns the Church leased property to tenants and claimed full judicial authority over these tenants, even when they committed crimes.10 Such conditions were irritating, but the major irritant was the flow of wealth from the English Church to the popes—i.e., in the fourteenth century, to Avignon—i.e., to France. It was estimated that more English money went to the pope than to the state or the king.11

An anticlerical party formed at the court. Laws were passed to make ecclesiastical property bear a larger and steadier share in the expenses of government. In 1333 Edward III refused to pay any longer the tribute that King John of England had pledged to the popes in 1213. In 1351 the Statute of Provisors sought to end papal control over the personnel or revenues of English benefices. The First Statute of Praemunire (1353) outlawed Englishmen who sued in “foreign” (papal) courts on matters claimed by the king to lie under secular jurisdiction. In 1376 the Commons officially complained that papal collectors in England were sending great sums of money to the pope, and that absentee French cardinals were drawing rich revenues from English sees.12

The anticlerical party at the court was led by John of Gaunt, whose protection enabled John Wyclif to die a natural death.

The first of the English reformers was born at Hipswell, near the village of Wyclif, in north Yorkshire about 1320. He studied at Oxford, became professor of theology there, and for a year (1360) was Master of Balliol College. He was ordained to the priesthood, and received from the popes various benefices or livings in parish churches, but continued meanwhile to teach at the University. His literary activity was alarming. He wrote vast Scholastic treatises on metaphysics, theology, and logic, two volumes of polemics, four of sermons, and a medley of short but influential tracts, including the famous Tractatus de civili dominio. Most of his compositions were in graceless and impenetrable Latin that should have made them harmless to any but grammarians. But hidden among these obscurities were explosive ideas that almost severed Britain from the Roman Church 155 years before Henry VIII, plunged Bohemia into civil war, and anticipated nearly all the reform ideas of John Huss and Martin Luther.

Putting his worse foot forward, and surrendering to Augustine’s logic and eloquence, Wyclif built his creed upon that awful doctrine of predestination which was to remain even to our day the magnet and solvent of Protestant theology. God, wrote Wyclif, gives His grace to whomever He wishes, and has predestined each individual, an eternity before birth, to be lost or saved through all eternity. Good works do not win salvation, but they indicate that he who does them has received divine grace and is one of the elect. We act according to the disposition that God has allotted to us; to invert Heraclitus, our fate is our character. Only Adam and Eve had free will; by their disobedience they lost it for themselves and for their posterity.

God is sovereign lord of us all. The allegiance that we owe Him is direct, as is the oath of every Englishman to the king, not indirect through allegiance to a subordinate lord, as in feudal France. Hence the relationship of man to God is direct, and requires no intermediary; any claim of Church or priest to be a necessary medium must be repelled.13 In this sense all Christians are priests, and need no ordination. God holds dominion over all the earth and the contents thereof; a human being can justly hold property only as His obedient vassal. Anyone who is in a state of sin—which constitutes rebellion against the Divine Sovereign—loses all right of possession, for rightful possession (“dominion”) requires a state of grace. Now it is clear from Scripture that Christ intended His Apostles, their successors, and their ordained delegates to have no property. Any church or priest that owns property is violating the Lord’s commandment, is therefore in a state of sin, and consequently cannot validly administer the sacraments. The reform most needed in Church and clergy is their complete renunciation of wordly goods.

As if this were not troublesome enough, Wyclif deduced from his theology a theoretical communism and anarchism. Any person in a state of grace shares with God the ownership of all goods; ideally everything should be held by the righteous in common.14 Private property and government (as some Scholastic philosophers had taught) are results of Adam’s sin (i.e., of human nature) and man’s inherited sinfulness; in a society of universal virtue there would be no individual ownership, no man-made laws of either Church or state.15 Suspecting that the radicals, who were at this time meditating revolt in England, would interpret this literally, Wyclif explained that his communism was to be understood only in an ideal sense; the powers that be, as Paul had taught, are ordained by God, and must be obeyed. This flirtation with revolution was almost precisely repeated by Luther in 1525.

The anticlerical party saw some sense, if not in Wyclif’s communism, at least in his condemnation of ecclesiastical wealth. When Parliament again refused to pay King John’s tribute to the pope (1366), Wyclif was engaged as peculiaris regis clericus—z cleric in the service of the king—to prepare a defense of the act.16 In 1374 Edward III gave him the rectory of Lutterworth, apparently as a retaining fee.17 In July 1376, Wyclif was appointed to the royal commission sent to Bruges to discuss with papal agents the continued refusal of England to pay the tribute. When John of Gaunt proposed that the government should confiscate part of the Church’s property, he invited Wyclif to defend the proposal in a series of sermons in London; Wyclif complied (September 1376), and was thereafter branded by the clerical party as a tool of Gaunt. Bishop Courtenay of London decided to attack Gaunt indirectly by indicting Wyclif as a heretic. The preacher was summoned to appear before a council of prelates at St. Paul’s in February 1377. He came, but accompanied by John of Gaunt with an armed retinue. The soldiers entered into a dispute with some spectators; a fracas ensued, and the bishop thought it discreet to adjourn. Wyclif returned unhurt to Oxford. Courtenay dispatched to Rome a detailed accusation quoting fifty-two passages from Wyclif’s works. In May, Gregory XI issued bulls condemning eighteen propositions, mostly from the treatise On Civil Dominion, and ordered Archbishop Sudbury and Bishop Courtenay to inquire whether Wyclif still held these views; if he did they were to arrest him and keep him in chains pending further instructions.

By this time Wyclif had won the support not only of John of Gaunt and Lord Percy of Northumberland but of a large body of public opinion as well. The Parliament that met in October was strongly anticlerical. The argument for disendowment of the Church had charms for many members, who reckoned that if the King should seize the wealth now held by English bishops, abbots, and priors, he could maintain with it fifteen earls, 1,500 knights, 6,200 squires, and have £20,000 a year left for himself.18 At this time France was preparing to invade England, and the English treasury was almost empty; how foolish it seemed to let papal agents collect funds from English parishes for a French pope and a college of cardinals overwhelmingly French! The King’s advisers asked Wyclif to prepare an opinion on the question ‘Whether the Realm of England can legitimately, when the necessity of repelling invasion is imminent, withhold the treasure of the Realm that it be not sent to foreign parts, although the pope demand it under pain of censure and in virtue of obedience to him?’ Wyclif answered in a pamphlet that in effect called for the severance of the English Church from the papacy. ‘The pope,’ he wrote, ‘cannot demand this treasure except by way of alms.... Since all charity begins at home, it would be the work not of charity but of fatuity to direct the alms of the Realm abroad when the Realm itself is in need of them.’ Against the contention that the English Church was part of, and should obey, the universal or Catholic Church, Wyclif recommended the ecclesiastical independence of England. ‘The Realm of England, in the words of Scripture, ought to be one body, and clergy, lords, and commonalty members of that body.’19 This anticipation of Henry VIII seemed so bold that the King’s advisers directed Wyclif to make no further statements on the matter.

The Parliament adjourned on November 28. On December 18 the embattled bishops published the condemnatory bulls, and bade the chancellor of Oxford to enforce the Pope’s order of arrest. The university was then at the height of its intellectual independence. In 1322 it had assumed the right to depose an unsatisfactory chancellor without consulting its formal superior, the Bishop of Lincoln; in 1367 it had thrown off all episcopal control. Half of the faculty supported Wyclif, at least in his right to express his opinions. The chancellor refused to obey the bishops, and denied the authority of any prelate over the university in matters of belief; meanwhile he counseled Wyclif to remain in modest seclusion for a while. But it is a rare reformer who can be silent. In March 1378, Wyclif appeared before the bishops’ assembly at Lambeth to defend his views. As the hearing was about to begin, the Archbishop received a letter from the mother of King Richard II deprecating any final condemnation of Wyclif; and in the midst of the proceedings a crowd forced its way in from the street and declared that the English people would not tolerate any Inquisition in England. Yielding to this combination of government and populace, the bishops deferred decision, and again Wyclif went home unhurt—indeed, triumphant. On March 27 Gregory XI died, and a few months later the Papal Schism divided and weakened the papacy, and the whole authority of the Church. Wyclif resumed the offensive, and issued tract after tract, many in English, extending his heresies and revolt.

He is pictured to us in these years as a man hardened by controversy and made puritan by age. He was no mystic; rather, a warrior and an organizer; and perhaps he carried his logic to merciless extremes. His talent for vituperation now disported itself freely. He denounced the friars for preaching poverty and accumulating collective wealth. He thought some monasteries were ‘dens of thieves, nests of serpents, houses of living devils.’20 He challenged the theory that the merits of the saints could be applied to the rescue of souls from purgatory; Christ and the Apostles had taught no doctrine of indulgences. ‘Prelates deceive men by feigned indulgences or pardons, and rob them cursedly of their money.... . Men be great fools that buy these bulls of pardon so dear.’21 If the pope had the power to snatch souls from purgatory, why did he not in Christian charity take them out at once?22 With mounting vehemence Wyclif alleged that ‘many priests .... defile wives, maidens, widows, and nuns in every manner of lechery,’23 and demanded that the crimes of the clergy should be punishable by secular courts. He excoriated curates who flattered the rich and despised the poor, who easily forgave the sins of the wealthy but excommunicated the indigent for unpaid tithes, who hunted and hawked and gambled, and related fake miracles.24 The prelates of England, he charged, ‘take poor men’s livelihood, but they do not oppose oppression’; they ‘set more price by the rotten penny than by the precious blood of Christ’; they pray only for show, and collect fees for every religious service that they perform; they live in luxury, riding fat horses with harness of silver and gold; ‘they are robbers .... malicious foxes .... ravishing wolves .... gluttons .... devils .... apes’;25 here even Luther’s language is forecast. ‘Simony reigns in all states of the Church.... The simony of the court of Rome does most harm, for it is most common, and under most color of holiness, and robs most our land of men and treasure.’26 The scandalous rivalry of the popes (in the Schism), their bandying of excommunications, their unashamed struggle for power, ‘should move men to believe in popes only so far as these follow Christ.’27 A pope or a priest ‘is a lord, yea, even ā king,’ in matters spiritual; but if he assumes earthly possessions, or political authority, he is unworthy of his office. ‘Christ had not whereon to rest His head, but men say this pope hath more than half the Empire.... . Christ was meek... the pope sits on his throne and makes lords to kiss his feet.’ 28 Perhaps, Wyclif gently suggested, the pope is the Antichrist predicted in the First Epistle of the Apostle John,29 the Beast of the Apocalypse,30 heralding the second coming of Christ.31

The solution of the problem, as Wyclif saw it, lay in separating the Church from all material possessions and power. Christ and his Apostles had lived in poverty; so should his priests.32 The friars and monks should return to the full observance of their rules, avoiding all property or luxury;33 priests ‘should with joy suffer temporal lordship to be taken from them’; they should content themselves with food and clothing, and live on freely given alms.34 If the clergy will not disendow themselves by a voluntary return to evangelical poverty, the state should step in and confiscate their goods. ‘Let lords and kings mend them’ and ‘constrain priests to hold to the poverty that Christ ordained.’35 Let not the king, in so doing, fear the curses of the pope, for ‘no man’s cursing hath any strength but inasmuch as God Himself curseth.’36 Kings are responsible to God alone, from Whom they derive their dominion. Instead of accepting the doctrine of Gregory VII and Boniface VIII that secular governments must be subject to the Church, the state, said Wyclif, should consider itself supreme in all temporal matters and should take control of all ecclesiastical property. Priests should be ordained by the king.37

The power of the priest lay in his right to administer the sacraments. Wyclif turned to these with a full anticipation of Luther and Calvin. He denied the necessity of auricular confession, and advocated a return to the voluntary public confession favored by the early Christians. ‘Privy confession made to priests... is not needful, but brought in late by the Fiend; for Christ used it not, nor any of His Apostles after Him.’38 It now makes men thralls to the clergy, and is sometimes abused for economic or political ends; and ‘by this privy shriving a friar and a nun may sin together.’39 Good laymen may absolve a sinner more effectively than wicked priests; but in truth only God can absolve. In general we should doubt the validity of a sacrament administered by a sinful or heretical priest. Nor can a priest, good or bad, change the bread and wine of the Eucharist into the physical body and blood of Christ. Nothing seemed to Wyclif more abominable than the thought that some of the priests whom he knew could perform such a Godcreating miracle.40 Like Luther, Wyclif denied transubstantiation, but not the Real Presence; by a mystery that neither pretended to explain, Christ was made ‘spiritually, truly, really, effectively’ present, but along with the bread and wine, which did not (as the Church taught) cease to exist.41

Wyclif would not admit that these ideas were heretical, but this theory of ‘consubstantiality’ alarmed some of his supporters. John of Gaunt hurried over to Oxford, and urged his friend to say no more about the Eucharist (1381). Wyclif rejected the advice, and reaffirmed his views in a Confessio dated May 10, 1381. A month later social revolution flared out in England, and frightened all property owners into discountenancing any doctrine that threatened any form of property, lay or ecclesiastical. Wyclif now lost most of his backing in the government, and the assassination of Archbishop Sudbury by the rebels promoted his most resolute enemy, Bishop Courtenay, to the primacy of England. Courtenay felt that if Wyclif’s conception of the Eucharist were allowed to spread, it would undermine the prestige of the clergy, and therefore also the foundation of the Church’s moral authority. In May 1382, he summoned a council of clergy to meet at the Blackfriars’ Convent in London. Having persuaded this assembly to condemn twenty-four propositions which he read from Wyclif’s works, he sent a peremptory command to the chancellor of Oxford to restrain the author from any further teaching or preaching until his orthodoxy should be proved. King Richard II, as part of his reaction to the uprising that had almost deposed him, ordered the chancellor to expel Wyclif and all his adherents. Wyclif retired to his living at Lutterworth, apparently still protected by John of Gaunt.

Embarrassed by the admiration expressed for him by the priest John Ball, a chief protagonist of the revolt, Wyclif issued several tracts dissociating himself from the rebels; he disclaimed any socialist views, and urged his followers to submit patiently to their terrestrial lords in the firm hope of recompense after death.42 Nevertheless he continued his pamphleteering against the Church, and organized a body of ‘Poor Preaching Priests’ to spread his Reformation among the people. Some of these ‘Lollards’* were men of meager schooling, some were Oxford dons. All went robed in black wool and barefoot, like the early friars; all were warmed with the ardor of men who had rediscovered Christ. Theirs was already the Protestant emphasis on an infallible Bible as against the fallible traditions and dogmas of the Church, and on the sermon in the vernacular as against a mystic ritual in a foreign tongue.43 For these lay priests, and for their literate hearers, Wyclif wrote in rough and vigorous English some 300 sermons and many religious tracts. And since he urged a return to the Christianity of the New Testament, he set himself and his aides to translate the Bible as the sole and unerring guide to true religion. Till that time (1381) only small portions of Scripture had been rendered into English; a French translation was known to the educated classes, and an Anglo-Saxon version, unintelligible to Wyclif’s England, had come down from King Alfred’s time. The Church, finding that heretics like the Waldensians made much use of the Bible, had discouraged the people from reading unauthorized translations,44 and had deprecated the creedal chaos that she expected when every party should make and color its own translation, and every reader be free to make his own interpretation, of the Scriptural text. But Wyclif was resolved that the Bible should be available to any Englishman who could read. He appears to have translated the New Testament himself, leaving the Old Testament to Nicholas Hereford and John Purvey. The whole was finished some ten years after Wyclif’s death.

The translation was made from Jerome’s Latin version, not from the Hebrew of the Old Testament or the Greek of the New. It was not a model of English prose, but it was a vital event in English history.

In 1384 Pope Urban VI summoned Wyclif to appear before him in Rome. A different summons exceeded it in authority. On December 28, 1384, the ailing reformer suffered a paralytic stroke as he was attending Mass, and three days later he died. He was buried in Lutterworth, but by a decree of the Council of Constance (May 4, 1415) his bones were dug up and cast into a near-by stream.45 Search was made for his writings, and as many as were found were destroyed.

All the major elements of the Reformation were in Wyclif: the revolt against the worldliness of the clergy, and the call for a sterner morality; the return from the Church to the Bible, from Aquinas to Augustine, from free will to predestination, from salvation by works to election by divine grace; the rejection of indulgences, auricular confession, and transubstantiation; the deposition of the priest as an intermediary between God and man; the protest against the alienation of national wealth to Rome; the invitation to the state to end its subordination to the papacy; the attack (preparing for Henry VIII) on the temporal possessions of the clergy. If the Great Revolt had not ended the government’s protection of Wyclif’s efforts, the Reformation might have taken form and root in England 130 years before it broke out in Germany.

III. THE GREAT REVOLT: 1381

England and Wales had in 1307 a population precariously estimated at 3,000,000—a slow increase from a supposed 2,500,000 in 1066.46 The figures suggest a sluggish advance of agricultural and industrial techniques—and an effective control of human multiplication by famine, disease, and war—in a fertile but narrow island never meant to sustain with its own resources any great multitude of men. Probably three fourths of the people were peasants, and half of these were serfs; in this regard England lagged a century behind France.

Class distinctions were sharper than on the Continent. Life seemed to revolve about two foci: gracious or arrogant lordship at one end, hopeful or resentful service at the other. The barons, aside from their limited duties to the king, were masters of all they surveyed, and of much beyond. The dukes of Lancaster, Norfolk, and Buckingham had estates rivaling those of the Crown, and the Nevilles and Percys had hardly less. The feudal lord bound his vassal knights and their squires to serve and defend him and wear his “livery.”* Nevertheless one might rise from class to class; a rich merchant’s daughter could catch a noble and a title, and Chaucer, reborn, would have been startled to find his granddaughter a duchess. The middle classes assumed such manners of the aristocracy as they could manage; they began to address one another as Master in England, Mon seigneur in France; soon every man was a Mister or Monsieur, and every woman a Mistress or Madame.†

Industry progressed faster than agriculture. By 1300 almost all the coalfields of Britain were being worked; silver, iron, lead, and tin were mined, and the export of metals ranked high in the nation’s foreign trade; it was a common remark that “the kingdom is of greater value under the land than above.” 47 The woolen industry began in this century to make England rich. The lords withdrew more and more lands from the common uses formerly allowed to their serfs and tenants, and turned large tracts into sheep enclosures; more money could be made by selling wool than by tilling the land. The wool merchants were for a time the wealthiest traders in England, able to yield great sums in loans and taxes to Edward III, who ruined them. Tired of seeing raw wool go from England to feed the clothing industry of Flanders, Edward (1331 f.) lured Flemish weavers to Britain, and through their instruction established a textile industry there. Then he forbade the export of wool and the import of most foreign cloth. By the end of the fourteenth century the manufacture of clothing had replaced the trade in wool as the main source of England’s liquid wealth and had reached a semi-capitalistic stage.

The new industry required the close co-operation of many crafts—weaving, fulling, carding, dyeing, finishing; the old craft guilds could not arrange the disciplined collaboration needed for economical production; enterprising masters—entrepreneurs—gathered diverse specializations of labor into one organization, which they financed and controlled. However, no such factory system arose here as in Florence and Flanders; most of the work was still done in small shops by a master, his apprentices, and a few journeymen, or in little rural mills using water power, or in country homes where patient fingers plied the loom when household chores allowed. The craft guilds fought the new system with strikes, but its superior productivity overrode all opposition; and the workers who competed to sell their toil and skill were increasingly at the mercy of men who furnished capital and management. Town proletarians “lived from hand to mouth .... indifferently clad and housed, in good times well fed, but in bad times not fed at all.” 48 All male inhabitants of English cities were subject to conscription of their labor for public works, but rich men could pay for substitutes.49 Poverty was bitter, though probably less extreme than in the early nineteenth century. Beggars abounded, and organized to protect and govern their profession. Churches, monasteries, and guilds provided a limping charity.

Upon this scene the Black Death burst as not only a catastrophic visitation but almost as an economic revolution. The English people lived in a climate more favorable to vegetation than to health; the fields were green the year round, but the population suffered from gout, rheumatism, asthma, sciatica, tuberculosis, dropsy, and diseases of eyes and skin.50 All classes ate a heavy diet and kept warm with alcoholic drinks. “Few men now reach the age of forty,” said Richard Rolle about 1340, “and fewer still the age of fifty.”51 Public sanitation was primitive; the stench of tanneries, pigsties, and latrines sullied the air; only the well-to-do had running water piped into their homes; the majority fetched it from conduits or wells and could not waste it on weekly baths.52 The lower classes offered ready victims for the pestilences that periodically decimated the population. In 1349 the bubonic plague crossed from Normandy to England and Wales, and thence a year later into Scotland and Ireland; it returned to England in 1361, 1368, 1375, 1382, 1390, 1438, 1464; all in all it carried away one Englishman out of every three.53 Nearly half the clergy died; perhaps some of the abuses later complained of in the English Church were due to the necessity of hastily impressing into her service men lacking the proper qualifications of training and character. Art suffered; ecclesiastical building almost stopped for a generation. Morals suffered; family ties were loosed, sexual relations overflowed the banks within which the institution of marriage sought to confine them for social order’s sake. The laws lacked officers to enforce them, and were frequently ignored.

The plague collaborated with war to quicken the decline of the manorial system. Many peasants, having lost their children or other aides, deserted their tenancies for the towns; landowners were obliged to hire free workers at twice the former wage, to attract new tenants with easier terms than before, and to commute feudal services into money payments. Themselves forced to pay rising prices for everything that they bought, the landlords appealed to the government to stabilize wages. The Royal Council responded (June 18, 1349) with an ordinance substantially as follows:

Because a great part of the People, and especially of Workers and Servants, late died of the pestilence, and many... will not serve unless they receive excessive wages, and some rather willing to beg in idleness than by Labour to get their Living; We, considering the grievous Discommodity which, of the lack especially of Plowmen and such Labourers, may hereafter come, have upon deliberation and treaty with the Prelates and the Nobles, and Learned Men assisting us, of their mutual Counsel ordained:

1. Every person able in Body and under the Age of sixty Years, not having [wherewith] to live, being required, shall be bound to serve him that doth require him, or else [be] committed to the Gaol, until he find Surety to serve.

2. If a Workman or Servant depart from Service before the time agreed upon, he shall be imprisoned.

3. The old Wages, and no more, shall be given to Servants.....

5. If any Artificer or Workman take more wages than were wont to be paid, he shall be committed to the Gaol.....

6. Victuals shall be sold at reasonable prices.

7. No person shall give anything to a Beggar that is able to labour.54

This ordinance was so widely disregarded by employers and employees that Parliament issued (February 9,1351) a Statute of Labourers, specifying that no wages should be paid above the 1346 rate, fixing definite prices for a large number of services and commodities, and establishing enforcement machinery. A further act of 1360 decreed that peasants who left their lands before the term of their contract or tenancy expired might be brought back by force, and, at the discretion of the justices of the peace, might be branded on the brow.55 Similar measures, of increasing severity, were enacted between 1377 and 1381. Wages rose despite them, but the strife so engendered between laborers and government inflamed the conflict of classes, and lent new weapons to the preachers of revolt.

The rebellion that ensued had a dozen sources. Those peasants who were still serfs demanded freedom; those who were free called for an end to feudal dues still required of them; and tenants urged that the rent of land should be lowered to four pence ($1.67?) per acre per year. Some towns were still subject to feudal overlords, and longed for self-government. In the liberated communities the workingmen hated the mercantile oligarchy, and journeymen protested against their insecurity and poverty. All alike—peasants, proletarians, even parish priests—denounced the governmental mismanagement of Edward Ill’s last years, of Richard II’s earliest; they asked why English arms had so regularly been beaten after 1369, and why such heavy taxes had been raised to finance such defeats. They particularly abominated Archbishop Sudbury and Robert Hales, the chief ministers of the young king, and John of Gaunt as the front and protector of governmental corruption and incompetence.

The Lollard preachers had little connection with the movement, but they had shared in preparing minds for the revolt. John Ball, the intellectual of the rebellion, quoted Wyclif approvingly, and Wat Tyler followed Wyclif in demanding disendowment of the Church. Ball was the “mad priest of Kent” (as Froissart called him) who taught communism to his congregation, and was excommunicated in 1306.56 He became an itinerant preacher, denouncing the wicked wealth of prelates and lords, calling for a return of the clergy to evangelical poverty, and making fun of the rival popes who, in the Schism, were dividing the garments of Christ.57 Tradition ascribed to him a famous couplet:

When Adam delved and Eve span

Who was then the gentleman? 58

—i.e., when Adam dug in the earth and Eve plied the loom, were there any class divisions in Eden? Froissart, though so fond of the English aristocracy, quoted Ball’s alleged views at sympathetic length:

My good friends, matters cannot go on well in England until all things shall be in common; when there shall be neither vassals nor lords, when the lords shall be no more masters than ourselves. How ill they behave to us! For what reason do they thus hold us in bondage? Are we not all descended from the same parents, Adam and Eve? And what can they show why they should be more masters than ourselves?... We are called slaves, and if we do not perform our service we are beaten.... . Let us go to the King and remonstrate with him; he is young, and from him we may obtain a favorable answer; and if not we must ourselves seek to amend our condition.59

Ball was thrice arrested, and when the revolt broke out he was in jail.

The poll tax of 1380 capped the discontent. The government was nearing bankruptcy, the pledged jewels of the king were about to be forfeited, the war in France was crying out for new funds. A tax of £ 100,000 ($10,000,000?) was laid upon the people, to be collected from every inhabitant above the age of fifteen. All the diverse elements of revolt were united by this fresh imposition. Thousands of persons evaded the collectors, and the total receipts fell far short of the goal. When the government sent new commissioners to ferret out the evaders, the populace gathered in force and defied them; at Brentwood the royal agents were stoned out of the town (1381), and like scenes occurred at Fobbing, Corringham, and St. Albans. Mass meetings of protest against the tax were held in London; they sent encouragement to the rural rebels, and invited them to march upon the capital, to join the insurgents there, and “so press the King that there should no longer be a serf in England.”60

A group of collectors entering Kent met a riotous repulse. On June 6, 1381, a mob broke open the dungeons at Rochester, freed the prisoners, and plundered the castle. On the following day the rebels chose as their chief Wat Tegheler, or Tyler. Nothing is known of his antecedents; apparently he was an ex-soldier, for he disciplined the disorderly horde into united action, and won its quick obedience to his commands. On June 8 this swelling multitude, armed with bows and arrows, cudgels, axes, and swords, and receiving recruits from almost every village in Kent, attacked the homes of unpopular landlords, lawyers, and governmental officials. On June 10 it was welcomed into Canterbury, sacked the palace of the absent Archbishop Sudbury, opened the jail, and plundered the mansions of the rich. All eastern Kent now joined in the revolt; town after town rose, and local officials ran before the storm. Rich men fled to other parts of England, or concealed themselves in out-of-the-way places, or escaped further damage by making a contribution to the rebel cause. On June 11 Tyler turned his army toward London. At Maidstone it delivered John Ball from jail; he joined the cavalcade, and preached to it every day. Now, he said, would begin that reign of Christian democracy which he had so long dreamed of and pled for; all social inequalities would be leveled; there would no longer be rich and poor, lords and serfs; every man would be a king.61

Meanwhile related uprisings occurred in Norfolk, Suffolk, Beverly, Bridgewater, Cambridge, Essex, Middlesex, Sussex, Hertford, Somerset. At Bury St. Edmund the people cut off the head of the prior, who had too stoutly asserted the feudal rights of the abbey over the town. At Colchester the rioters killed several Florentine merchants who were believed to be cutting in on British trade. Wherever possible they destroyed the rolls, leases, or charters that recorded feudal ownership or bondage; hence the townsfolk of Cambridge burned the charters of the University; and at Waltham every document in the abbey archives was committed to the flames.

On June 11 a rebel army from Essex and Hertford approached the northern outskirts of London; on the twelfth the Kent insurgents reached Southwark, just across the Thames. No organized resistance was offered by the adherents of the King. Richard II, Sudbury, and Hales hid in the Tower. Tyler sent the King a request for an interview; it was refused. The mayor of London, William Walworth, closed the city gates, but they were reopened by revolutionists within the town. On June 13 the Kent forces marched into the capital, were welcomed by the people, and were joined by thousands of laborers. Tyler held his host fairly well in leash, but appeased its fury by allowing it to sack the palace of John of Gaunt. Nothing was stolen there; one rioter who tried to filch a silver goblet was killed by the crowd. But everything was destroyed; costly furniture was thrown out of the windows, rich hangings were torn to rags, jewelry was smashed to bits; then the house was burned to the ground, and some jolly rebels who had drunk themselves to stupor in the wine cellar were forgotten and consumed in the flames. Thereafter the army turned on the Temple, citadel of the lawyers of England; the peasants remembered that lawyers had written the deeds of their servitude, or had assessed their holdings for taxation; there too they made a holocaust of the records, and burned the buildings to the ground. The jails in Newgate and the Fleet were destroyed, and the happy inmates joined the mob. Wearied with its efforts to crowd a century of revenge into a day, the multitudes lay down in the open spaces of the city, and slept.

That evening the King’s Council thought better of its refusal to let him talk with Tyler. They sent an invitation to Tyler and his followers to meet with Richard the next morning at a northern suburb known as Mile End. Shortly after dawn on June 14 the fourteen-year-old King, risking his life, rode out of the Tower with all of his council except Sudbury and Hales, who dared not expose themselves. The little party made its way through the hostile crowd to Mile End, where the Essex rebels were already gathered; part of the Kent army followed, with Tyler at its head. He was surprised at the readiness of Richard to grant nearly all demands. Serfdom was to be abolished throughout England, all feudal dues and services were to end, the rental of the tenants would be as they had asked; and a general amnesty would absolve all those who had shared in the revolt. Thirty clerks were at once set to work drawing up charters of freedom and forgiveness for all districts that applied. One demand the King refused—that the royal ministers and other “traitors” should be surrendered to the people. Richard replied that all persons accused of misconduct in government would be tried by orderly process of law, and would be punished if found guilty.

Not satisfied with this answer, Tyler and a selected band rode rapidly to the Tower. They found Sudbury singing Mass in the chapel. They dragged him out into the courtyard and forced him down with his neck on a log. The executioner was an amateur, and required eight strokes of the ax to sever the head. The insurgents then beheaded Hales and two others. Upon the Archbishop’s head they fixed his miter firmly with a nail driven into the skull; they mounted the heads on pikes, carried them in procession through the city, and set them up over the gate of London Bridge. All the remainder of that day was spent in slaughter. London tradesmen, resenting Flemish competition, bade the crowd kill every Fleming found in the capital. To determine the nationality of a suspect he was shown bread and cheese and bidden name them; if he answered brod und käse, or spoke with a Flemish brogue, he forfeited his life. Over 150 aliens—merchants and bankers—were slain in London on that day in June, and many English lawyers, tax collectors, and adherents of John of Gaunt fell under the axes and hatchets of indiscriminate vengeance. Apprentices murdered their masters, debtors their creditors. At midnight the sated victors again retired to rest.

Informed of these events, the King returned from Mile End and went, not to the Tower, but to his mother’s rooms near St. Paul’s. Meanwhile a large number of the Essex and Hertford contingents, rejoicing in their charters of freedom, dispersed toward their homes. On June 15 the King sent a modest message to the remaining rebels asking them to meet him in the open spaces of Smithfield outside Aldersgate. Tyler agreed. Before keeping this rendezvous, Richard, fearing death, confessed and took the Sacrament; then he rode out with a retinue of 200 men whose peaceful garb hid swords. At Smithfield Tyler came forward with only a single companion to guard him. He made new demands, uncertainly reported, but apparently including the confiscation of Church property and the distribution of the proceeds among the people.62 A dispute ensued; one of the King’s escort called Tyler a thief; Tyler directed his aide to strike the man down; Mayor Walworth blocked the way; Tyler stabbed at Walworth, whose life was saved by the armor under his cloak; Walworth wounded Tyler with a short cutlass, and one of Richard’s squires ran Tyler through twice with a sword. Tyler rode back to his host crying treason, and fell dead at their feet. Shocked by what seemed to them plain treachery, the rebels set their arrows and prepared to shoot. Though their numbers were reduced, they were still a substantial force, reckoned by Froissart at 20,000; probably they could have overwhelmed the King’s retinue. But Richard now rode out bravely toward them, crying out, “Sirs, will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain; you shall have from me that which you seek. Only follow me into the fields without.” He rode out slowly, not sure that they would heed or spare him. The insurgents hesitated, then followed him, and most of the royal guard mingled in their midst.

Walworth, however, turned sharply back, galloped into the city, and sent orders to the aldermen of its twenty-four wards to join him with all the armed forces they could muster. Many citizens who at first had sympathized with the revolt were now disturbed by the murders and pillage; every man who had any property felt his goods and his life to be in peril; so the Mayor found an impromptu army of 7,000 men rising at his command as if out of the earth. These he led back to Smithfield; there he rejoined and surrounded the King, and offered to massacre the rebels. Richard refused; the rebels had spared him when he was at their mercy, and he would not now show himself less generous. He announced to them that they were free to depart in safety. The Essex and Hertford remnants rapidly melted away; the London mutineers disappeared into their haunts; only the Kent contingent stayed. Their passage through the city was blocked by Walworth’s armed men, but Richard ordered that no one should molest them; they marched off in safety, and filed back in disorder along the Old Kent Road. The King returned to his mother, who greeted him with tears of happy relief. “Ah, fair son, what pain and anguish have I had for you this day!” “Certes, Madam,” the boy answered. “I know it well. But now rejoice and praise God, for today I have recovered my heritage that was lost, and the realm of England too.” 63

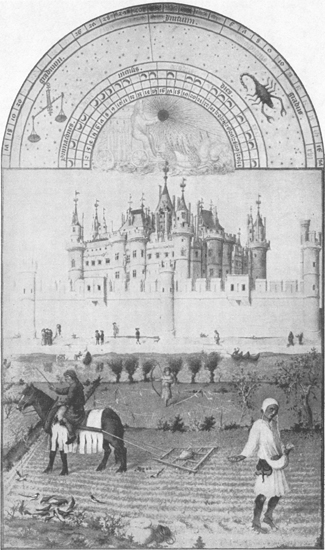

Fig. 1—POL DE LIMBURG: The Month of October, a miniature from Les Très Riches Heures du Due de Berry. Musée Condé, Chantilly

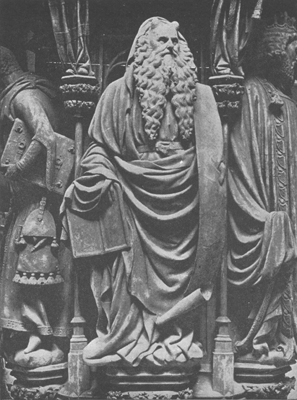

Fig. 2—CLAUS SLUTER: Moses. Museum, Dijon

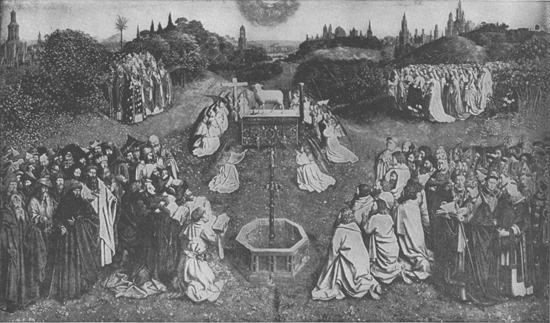

Fig. 3—HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK: The Virgin, detail from The Adoration of the Lamb. Church of St. Bavon, Ghent

Fig. 4—HUBERT AND JAN VAN EYCK: The Adoration of the lamb. Church of St. Bavon, Ghent

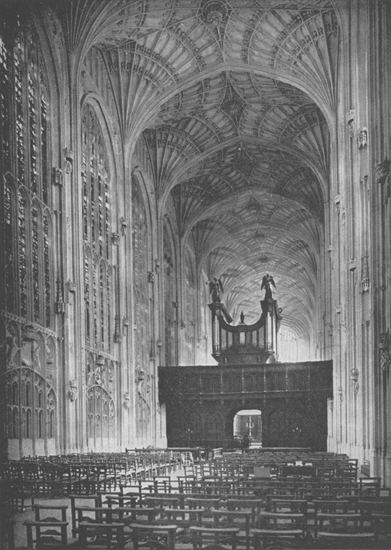

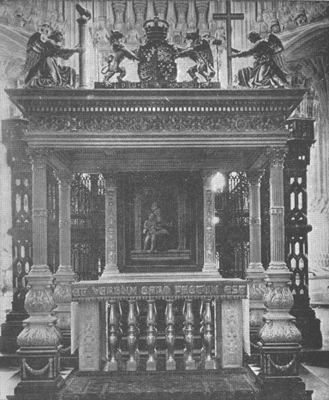

Fig. 5—King’s College Chapel (interior), Cambridge

Fig. 6—Chapel of Henry VII, Westminster Abbey, London

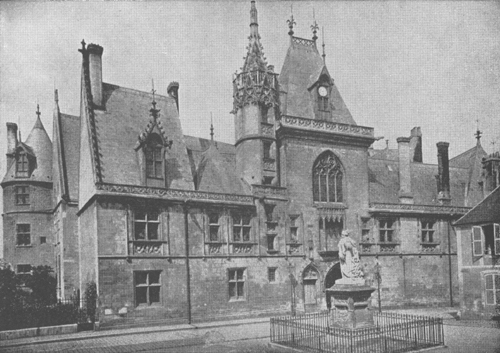

Fig. 7—House of Jacques Cœur, Bourges

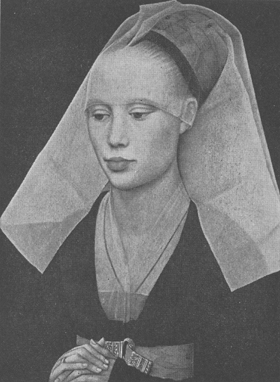

Fig. 8—ROGIER VAN DER WEYDEN: Portrait of a Lady. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (Mellon Collection)

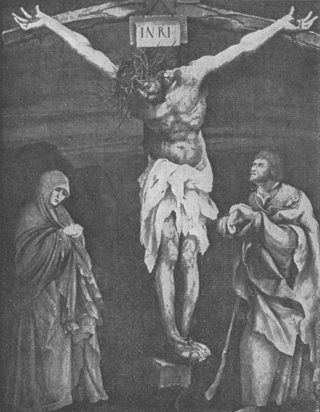

Fig. 9—MATTHIAS GRÜNE-WALD: The Crucifixion, detail from the Isenheim Altarpiece. Museum, Colmar

Fig. 10—ALBRECHT DÜRER: Portrait of Hieronymus Holzschuher. Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin

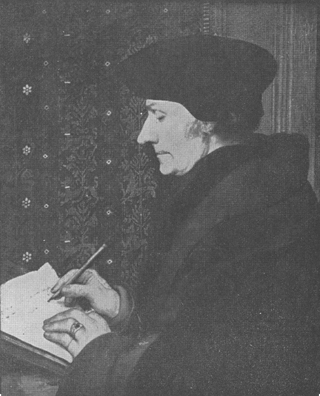

Fig. 11—HANS HOLBEIN THE YOUNGER: Erasmus. Louvre, Paris

Fig. 12—ALBRECHT DÜRER: The Four Apostles (at left: John and Peter; at right: Mark and Paul). Haus der Kunst, Munich

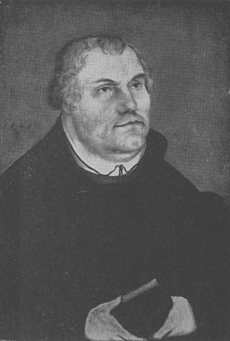

Fig. 13—LUCAS CRANACH: Martin Luther. The John G. Johnson Art Collection, Philadelphia

Fig. 14—Luther Memorial, Worms

Fig. 15—ALBRECHT DÜRER: Philip Melanchthon. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

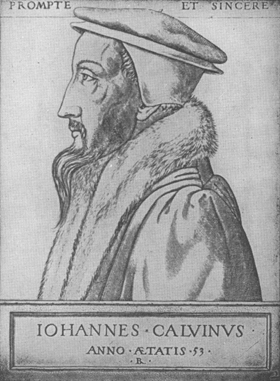

Fig. 16—RENÉ BOYVIN: Calvin. Bibliothèque Publique et Universitaire, Geneva

Fig. 17—Reformation Monument, Geneva

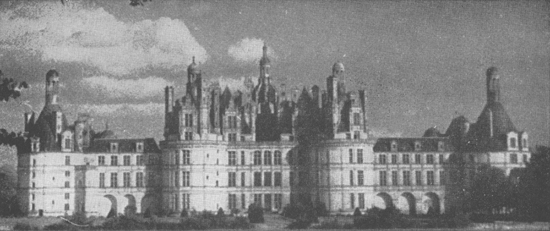

Fig. 18—Chateau of Francis I, Chambord

Fig. 19—Gallery of Francis I, Fontainebleau

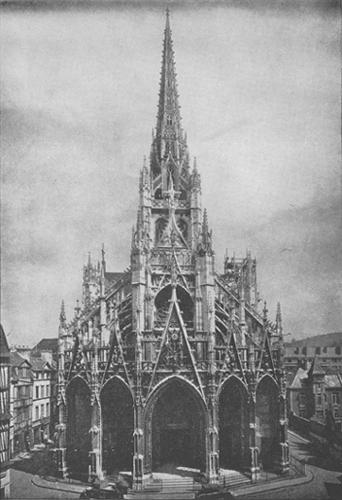

Fig. 20—Church of St. Maclou, Rouen

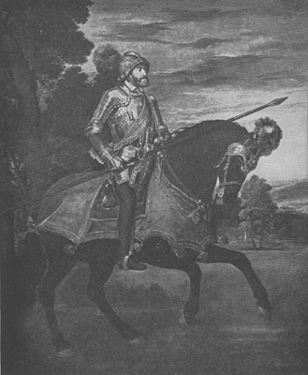

Fig. 21—TITIAN: Charles V at Mühlberg. Prado, Madrid

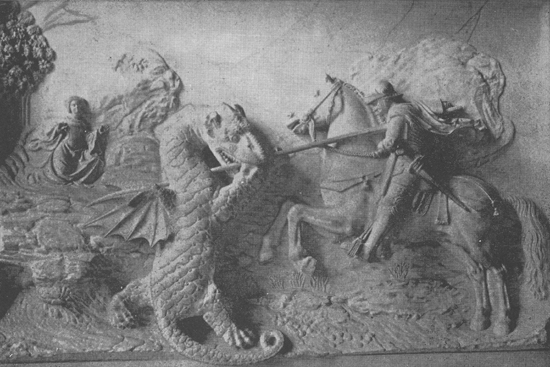

Fig. 22—MICHEL COLOMBE: St. George and the Dragon. Louvre, Paris

Fig. 23—JEAN GOUJON: Water Nymphs, from Fountain of the Innocents. Louvre, Paris

Fig. 24—JEAN CLOUET: Francis L Louvre, Paris

Probably under the prodding of the Mayor who had saved him, Richard on that same June 15 issued a proclamation banishing from London, on pain of death, all persons who had not lived there for a year past. Walworth and his troops searched streets and tenements for such aliens, caught many, killed several. Among these was one Jack Straw, who confessed, presumably under torture, that the men of Kent had planned to make Tyler king. In the meantime a deputation from the Essex insurgents arrived at Waltham and demanded of the King a formal ratification of the promises he had made on June 14. Richard replied that these had been made under duress, and that he had no intention of keeping them; on the contrary, he told them, “Villeins you are still, and villeins you shall remain”; and he threatened dread vengeance on any man who continued in armed rebellion.64 The angry deputies called upon their followers to renew the revolt; some did, but these were cut down with great slaughter by Walworth’s men (June 28).

On July 2 the embittered King revoked all charters and amnesties granted by him during the outbreak, and opened the way to a judicial inquiry into the identity and actions of the main participants. Hundreds were arrested and tried; 110 or more were put to death. John Ball was caught at Coventry; he fearlessly avowed his leading role in the insurrection, and refused to ask pardon of the King. He was hanged, drawn, and quartered; and his head, with those of Tyler and Jack Straw, replaced those of Sudbury and Hales as adornments of London Bridge. On November 13 Richard laid before Parliament an account of his actions; if, he said, the assembled prelates and lords and commons wished the serfs to be freed, he was quite willing. But the members were nearly all landowners; they could not admit the right of the King to dispose of their property; they voted that all existing feudal relations should be maintained.65 The beaten peasants returned to their plows, the sullen workers to their looms.

IV. THE NEW LITERATURE

The English language was becoming by slow stages a fit vehicle for literature. The Norman invasion of 1066 had stopped the evolution of Anglo-Saxon into English, and for a time French was the official language of the realm. Gradually a new vocabulary and idiom formed, basically Germanic, but mingled and adorned with Gallic words and turns. The long war with France may have spurred the nation to rebel against this linguistic domination by an enemy. In 1362 English was declared to be the language of law and the courts; and in 1363 the chancellor set a precedent by opening Parliament with an English address. Scholars, chroniclers, and philosophers (even till Francis Bacon) continued to write in Latin to reach an international audience, but poets and dramatists henceforth spoke the speech of England.

The oldest drama extant in English was a “mystery”—a dramatic representation of a religious story—performed in the Midlands, about 1350, under the title of The Harrowing of Hell, which staged a duel in words, at the mouth of hell, between Satan and Christ, In the fourteenth century it became customary for the guilds of a town to present a cycle of mysteries: a guild would prepare a scene, usually from the Bible, carry the setting and the actors on a float, and act the scenes on temporary stages built at populous centers in the city; and on successive days other guilds would present later scenes from the same Biblical narrative. The earliest such cycle now known is that of the Chester mysteries of 1328; by 1400 similar cycles were presented in York, Beverly, Cambridge, Coventry, Wakefield, Towneley, and London. As early as 1182 the Latin mysteries had developed a variety called the “miracle,” centering around the miracle or sufferings of some saint. About 1378 another variety appeared—the “morality”—which pointed a moral by acting a tale; this form would reach its peak in Everyman (c. 1480). Early in the fifteenth century we hear of still another dramatic form, doubtless then already old: the interlude, not a play between plays but a ludus—a play or show—carried on between two or more actors. Its subject was not restricted to religion or morality, but might be secular, humorous, profane, even obscene. Minstrel troupes played interludes in baronial or guild halls, in town or village squares, or in the courtyard of a frequented inn. In 1348 Exeter raised the first-known English theater, the first European building, since classic Roman structures, specifically and regularly devoted to dramatic representations.66 From the interludes would evolve the comedies, and from the mysteries and moralities would develop the tragedies, of the lusty Elizabethan stage.

The first major poem—one of the strangest and strongest poems—in the English language called itself The Vision of William Concerning Piers the Plowman. Nothing is known of the author except through his poem; assuming that this is autobiographical, we may name him William Langland and place his birth near 1332. He took minor orders, but never became a priest; he wandered to London and earned something short of starvation by singing Psalms at Masses for the dead. He lived dissolutely, sinned with “covetousness of eyes and concupiscence of the flesh,” had a daughter, perhaps married her mother, and dwelled with them in a hovel in Cornhill. He describes himself as a tall, gaunt figure, dressed in a somber robe befitting the gray disillusionment of his hopes. He was fond of his poem, issued it thrice (1362, 1377, 1394), and each time spun it out to greater length. Like the Anglo-Saxon poets, he used no rhyme, but alliterative verse of irregular meter.

He begins by picturing himself as falling asleep on a Malvern hill, and seeing in a dream a “field full of folk”—multitudes of rich, poor, good, bad, young, old—and amid them a fair and noble lady whom he identifies with Holy Church. He kneels before her and begs for “no treasure, but tell me how I may save my soul.” She replies:

When all treasures are tried, Truth is

best....

Whoso is true of his tongue, and telleth naught but that,

And doeth the works therewith, and willeth no

man ill,

He is a god by the gospel...and like to Our Lord.67

In a second dream he visions the Seven Deadly Sins, and under each head he indicts the wickedness of man in a powerful satire. For a time he abandons himself to cynical pessimism, awaiting an early end of the world. Then Piers (Peter) the Plowman enters the poem. He is a model farmer, honest, friendly, generous, trusted by all, working hard, living faithfully with his wife and children, and always a pious son of the Church. In later visions William sees the same Piers as the human Christ, as Peter the Apostle, as a pope, then as vanishing in the Papal Schism and the advent of Antichrist. The clergy, says the poet, are no longer a saving remnant; many of them have become corrupt; they deceive the simple, absolve the rich for a consideration, traffic in sacred things, sell heaven itself for a coin. What is a Christian to do in such a universal debacle? He must, says William, go forth again, over all intervening institutions and corruptions, and seek the living Christ Himself.68

Piers the Plowman contains its quota of nonsense, and its obscure allegories weary any reader who lays upon authors the moral obligation to be clear. But it is a sincere poem, flays rascals impartially, pictures the human scene vividly, rises through touches of feeling and beauty to a place second only to the Canterbury Tales in the English literature of the fourteenth century. Its influence was remarkable; Piers became for the rebels of England a symbol of the righteous, fearless peasant; John Ball recommended him to the Essex insurgents of 1381; as late as the Reformation his name was invoked in criticizing the old religious order and demanding a new.69 In ending his visions, the poet returned from Piers the pope to Piers again the peasant; if all of us, he concluded, were, like Piers, simple, practicing Christians, that would be the greatest, the final revolution; no other would ever be needed.

John Gower is a less romantic poet and figure than the mysterious Langland. He was a rich landowner of Kent who imbibed too much scholastic erudition, and achieved dullness in three languages. He, too, attacked the faults of the clergy; but he trembled at the heresies of the Lollards, and marveled at the insolence of peasants who, once content with beer and corn, now demanded meat and milk and cheese. Three things, said Gower, are merciless when they get out of hand: water, fire, and the mob. Disgusted with this world, worried about the next, “moral Gower” retired in old age to a priory, and spent his closing year in blindness and prayer. His contemporaries admired his morals, regretted his temper and his style, and turned with relief to Chaucer.

V. GEOFFREY CHAUCER: 1340–1400

He was a man full of the blood and beer of Merrie England, capable of taking in his stride the natural difficulties of life, drawing their sting with a forgiving humor, and picturing all phases of the English scene with a brush as broad as Homer’s, a spirit as lusty as Rabelais’.

His name, like so much of his language, was of French origin; it meant shoemaker, and probably was pronounced shosayr; posterity plays tricks with our very names, and remembers us only to remake us to its whim. He was the son of John Chaucer, a London vintner. He won a good education from both books and life; his poetry abounds in knowledge of men and women, literature and history. In 1357 “Geoffret Chaucer” was officially listed in the service of the household of the future Duke of Clarence. Two years later he was off to the wars in France; he was captured, but was freed for a ransom, to which Edward III contributed. In 1367 we find him a “yeoman of the King’s Chamber,” with a life pension of twenty marks ($1,333?) a year. Edward traveled much with his household at his heels; presumably Chaucer accompanied him, savoring England as he went. In 1366 he married Philippa, a lady serving the Queen, and lived with her in moderate discord till her death.70 Richard II continued the pension, and John of Gaunt added ten pounds ($1,000?) annually. There were other aristocratic gifts, which may explain why Chaucer, who saw so much of life, took little notice of the Great Revolt.

It was a pleasant custom of those days, which admired poetry and eloquence, to send men of letters on diplomatic missions abroad. So Chaucer was deputed with two others to negotiate a trade agreement at Genoa (1372); and in 1378 he went with Sir Edward Berkeley to Milan. Who knows but he may have met ailing Boccaccio, aging Petrarch? In any case, Italy was a transforming revelation to him. He saw there a culture far more polished, lettered, and subtle than England’s; he learned a new reverence for the classics, at least the Latin; the French influence that had molded his early poems yielded now to Italian ideas, verse forms, and themes. When finally he turned to his own land for his scenes and characters, he was an accomplished artist and a mature mind.

No man could then live in England by writing poetry. We might have supposed that Chaucer’s pensions would keep him adequately housed, fed, and clad; after 1378 they totaled some $10,000 in the money of our time; besides, his wife enjoyed her own pensions from John of Gaunt and the King. In any case, Chaucer felt a need to supplement his income by taking various governmental posts. For twelve years (1374–86) he served as “controller of the customs and subsidies,” and during that time he occupied lodgings over the Aldgate tower. In 1380 he paid an unstated sum to Cecilia Chaumpaigne for withdrawing her suit against him for rape.71 Five years later he was appointed justice of the peace for Kent; and in 1386 he had himself elected to Parliament. It was in the intervals of these labors that he wrote his poetry.

He describes himself, in The House of Fame, as hurrying home after he had “made his reckonings,” and losing himself in his books, sitting “dumb as a stone,” and living like a hermit in all but poverty, chastity, and obedience, and setting his “wit to make books, songs, and ditties in rime.” In his youth, he tells us, he had written “many a song and lecherous lay.”72 He translated Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae (The Consolation of Philosophy) into good prose, and part of Guillaume de Lorris’ Romaunt de la rose into excellent verse. He began a number of what may be called major minor poems: The House of Fame, The Book of the Duchess, The Parliament of Fowls, and The Legend of Good Women; he anticipated us in being unable to finish them. They were ambitious yet timid tentatives, frank imitations, in theme and form, of Continental origins.

In his finest single poem, Troilus and Criseyde, he continued to imitate, even to translate; but to 2,730 lines that he lifted from Boccaccio’s Filostrato he added 5,696 lines of other provenance or coined in his own mint. He made no attempt to deceive; he repeatedly referred to his source, and apologized for not translating it all. Such transfers from one literature to another were considered legitimate and useful, for even well-educated men could not then understand any vernacular but their own. Plots, as Greek and Elizabethan dramatists felt, were common property; art lay in the form.

Despite all discounts, Chaucer’s Troilus is the first great narrative poem in English. Scott called it “long and somewhat dull,” which it is; Rossetti called it “perhaps the most beautiful narrative poem of considerable length in the English language”;73 and this too is true. All long poems, however beautiful, become dull; passion is of poetry’s essence, and a passion that runs to 8,386 lines becomes prose almost as rapidly as desire consummated. Never were so many lines required to bring a lady to bed, and seldom has love hesitated, meditated, procrastinated, and capitulated with such magnificent and irrelevant rhetoric, and melodious conceits, and facile felicity of rhyme. Only Richardson’s Mississippi of prose could rival this Nile of verse in the leisurely psychology of love. Yet even the heavy-winged oratory, the infinite wordiness, the obstructive erudition obstinately displayed, fail to destroy the poem. It is, after all, a philosophic tale—of how woman is designed for love, and will soon love B if A stays too long away. It has one character livingly portrayed: Pandarus, who in the Iliad is the leader of the Lycian army in Troy, but here becomes the exuberant, resourceful, undiscourageable go-between to guide the lovers to their sin; and thereby hangs a word. Troilus is a warrior absorbed in repelling the Greeks, and scornful of men who, dallying on soft bosoms, become the thralls of appetite. He falls deliriously in love with Criseyde at first sight, and thereafter thinks of nothing else but her beauty, modesty, gentleness, and grace. Criseyde, after waiting anxiously through 6,000 lines for this timid soldier to announce his love, falls with relief into his arms, and Troilus forgets two worlds at once:

All other dredes weren from him fledde,

Both of the siege and his salvacioun.74

Having exhausted himself in achieving this ecstasy, Chaucer hurries over the bliss of the lovers to the tragedy that rescues it from boredom. Criseyde’s father having deserted to the Greeks, she is sent to them by the angry Trojans in exchange for the captured Antenor. The brokenhearted lovers part with vows of everlasting fidelity. Arrived among the Greeks, Criseyde is awarded to Diomedes, whose handsome virility so captivates his captive that—qual plum’ in vento—she surrenders in a page what before had been hoarded through a book. Perceiving which, Troilus plunges into battle seeking Diomedes, and finds death on Achilles’ spear. Chaucer ended his amorous epic with a pious prayer to the Trinity, and sent it, conscience-stricken, to “moral Gower, to correct of your benignitee.”

Probably in 1387 he began The Canterbury Tales. It was a brilliant scheme—to join a varied group of Britons at the Tabard Inn in Southwark (where Chaucer himself had emptied many a tankard of ale), ride with them on their vacation pilgrimage to the shrine of Becket at Canterbury, and put into their mouths the tales and thoughts that had gathered in the traveled poet’s head through half a century. Such devices for stitching stories together had been used many times before, but this was the best of all. Boccaccio had assembled for his Decameron only one class of men and women; he had not made them stand out as diverse personalities; Chaucer created an innful of characters so heterogeneously real that they seem truer to English life than the stuffed figures of history. They live and very literally move, they love and hate, laugh and cry; and as they jog along the road we hear not merely the tales they tell but their own troubles, quarrels, and philosophies.

Who will protest at quoting once more those spring-fresh opening lines?

Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote

The droghte of Marche hath perced to the rote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour,

Whan Zephyrus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

And smale fowles maken melodye,

That slepen al the night with open yë;...

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages ...

To feme halwes, couthe in sondry londes ...

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay

Redy to wenden on my pilgrimage

To Canterbury with ful devout corage,

At night was come in-to that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a companye,

Of sondry folk, by aventure y-falle

In felawshipe, and pilgrims were they alle,

That toward Canterbury wolden ryde.*

Then, one after another, Chaucer introduces them in the quaint sketches of his incomparable Prologue:

A Knyght ther was, and that a worthy man,

That fro the tyme that he first bigan

To ryden out, he loved chivalrye,

Trouthe and honour, fredom and curteisye ....

At mortal batailles hadde he been fiftene,

And foughten for our feith at Tramissene ....

And though that he were worthy, he was wys,

And of his port as meke as is a mayde.

He never yet no vileinye ne sayde

In al his lyf, unto no maner wight;

He was a verray parfit gentil knyght.

And the Knight’s son:

...

a yong Squyer,

A lovyere, and a lusty bacheler ....

So hote he lovede, that by nightertale [count of nights]

He sleep namore than dooth a nightingale.

And a Yeoman to serve the Knight and the Squire; and a most charming Prioress:

Ther was also a Nonne, a Pioresse,

That of hir smyling was ful simple and coy;

Hir gretteste ooth was by sëynt Loy [St. Louis];

And she was cleped madame Eglentyne.

Ful wel she song the service divyne,

Entuned in hir nose ful semely . ..

She was so charitable and pitous

She wolde wepe, if that she sawe a mous

Caught in a trappe, if it were deed or bledde.

Of smale houndes had she, that she fedde

With rosted flesh or milk and wastel-breed;

But sore weep she if oon of hem were deed

....

Of smal coral aboute her arm she bar

A peire of bedes, gauded al with grene;

And ther-on heng a broche of gold ful shene,

On which ther was first write a crowned A,

And after, Amor vincit omnia [Love conquers all].

Add another nun, three priests, a jolly monk “that lovede venerye” (i.e., hunting), and a friar unmatched in squeezing contributions out of pious purses.

For thogh a widow hadde noght a sho [shoe],

So plesaunt was his In principio,

Yet wolde he have a ferthing, er he wente.

Chaucer likes better the young student of philosophy:

A Clerk ther was of Oxenford also,

That un-to logik hadde longe y-go.

As lene was his hors as is a rake,

And he nas nat right fat, I undertake;

But loked holwe, and ther-to soberly.

Ful thredbar was his overest courtepy.

For he had geten him yet no benefyce,

Ne was so worldly for to have offyce.

For him was lever have at his beddes heed

Twenty bokes, clad in black or reed,

Of Aristotle and his philosophye,

Than robes riche, or filthele, or gay sautrye ...

Of studie took he most cure and most heed.

Noght o word spak he more than was nede ...

Souninge in moral vertu was his speche,

And gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.*

There was also a “Wife of Bath,” of whom more anon, and a poor Parson, “riche of holy thoght and werke,” and a Plowman, and a Miller, who “hade on the cop [top] of his nose a werte, and ther-on stood a tuft of heres reed as the bristles of a sowes eres”; and a “Maunciple” or buyer for an inn or a college; a “Reeve” or overseer for a manor; and a “Somnour” or server of summonses:

He was a gentil harlot [rogue] and a kinde;

A bettre felawe sholde men noght finde.

He wolde suffre, for a quart of wyn,

A good felawe to have his concubyn

A twelf-month, and excuse him atte fulle.

..

rood a gentil Pardoner ...

His wallet lay biforn him in his lappe,

Bret [brim] ful of pardouns come from Rome al hoot [hot].

And there was a Merchant, and a Man of Laws, a “Frankeleyn” or freeholder, a Carpenter, a Weaver, a Dyer, a “Tapier” or upholsterer, a Cook, and a Shipman. And there was Geoifrey Chaucer himself, standing shyly aside, “large” (fat) and difficult to embrace, and “looking forever upon the ground as if to find a hare.” And not least was mine host, owner of the Tabard Inn, who vows he has never entertained so merry a company; indeed, he offers to go with them and be their guide; and he suggests—to pass the fifty-six miles away—that each of the pilgrims shall tell two tales going and two on the return, and that he who tells the best “shal have a super at our aller cost” (a supper at the general expense) when they reach the inn again. It is agreed; the moving scene of this comédie humaine is set; the pilgrimage begins; and the courtly Knight tells the first story—of how two dear friends, Palamon and Arcite, see a lass gathering flowers in a garden, fall equally in love with her, and contend in a fatal joust for her as the complaisant prize.