Chapter eight. The art of the conversation

You’ve met with your client and gathered information. You’ve conducted thorough research, spent hours sketching, and worked on digitized versions of your strongest ideas. Now you’re ready to make that client presentation—a stage of the process that can cause undue pressure and anxiety.

If you’re one of many designers who gets nervous about this step and finds it a bit unpredictable, one way to alleviate pressure is to look at client presentations from a different angle. Delivering your ideas shouldn’t foster the worry associated with a “big reveal.” At the same time, this stage of the process is about much more than simply showing a few pictures and asking, “So, what do you reckon?”

Presentations are really nothing more than a conversation with your client. If you’ve kept in close contact throughout the design process—by listening to your client and responding thoughtfully, by clearly articulating how the process works, and by maintaining the dialogue with the decision-makers in the organization—then the presentation itself is just a continuation of that ongoing exchange.

But presentations are also about negotiation, just as much as they’re about the designs you’ve created. You need to be clear and concise with your explanations. You need to know how to persuade your client that your design (or one of them) is the best possible visual representation of her company. It’s also important to edit your thoughts so that everything you say has a valid reason for being said.

This chapter looks at the critical elements for successful conversations, as well as some of the conditions that are often inherent in unsuccessful ones. When you’re finished reading, you should have some sense of what presentation strategies you can use to get your clients to fully embrace at least some of your design ideas.

Deal with the decision-maker

In Chapter 4, I touched on the significance of dealing with the decision-maker during at least some phases of a project. From here I’ll refer to the decision-maker as the “committee,” since the clients you want to attract will probably have more than one person involved in choosing a visual identity.

Working directly with the committee for the duration of the project isn’t always possible—there’s a good chance you’ll be working with a single point of contact (perhaps a brand manager as opposed to a CEO or board of directors) at least some of the time up until this point. But when you’re ready to deliver your design ideas, dealing with the committee is critical. Otherwise it’s all too easy for your carefully crafted explanations to be distorted through a mediator.

I’ve seen—and previously been involved in—plenty of missed opportunities as a result of committee reviews, but just because you’re dealing with a team doesn’t mean the outcome will be one of those negative cases of “design by committee.”

By staying in control of the review process, you can use the strengths of each participant to iron out any kinks in your most distinctive and relevant ideas, and ultimately produce an iconic identity that both you and the committee as a whole are delighted by.

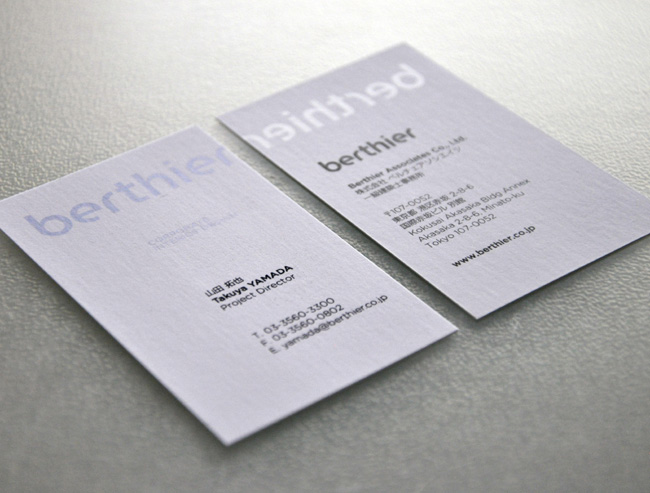

Back in 2008, I was working on an identity project for Tokyo-based Berthier Associates, an interior design firm with clients including Air France and Ferrari. Throughout the process I had the ideal point of contact—managing director Dominique Berthier—but because of who he was, I wrongly assumed there’d be no committee involvement. After all, I was dealing with the man who had the final say over the outcome. But I didn’t ask if anyone else would be involved.

Berthier had his own team of designers (or committee) at his disposal. Granted, they weren’t graphic designers—instead, they were interior designers. But the elements in play, such as line, space, texture, color, tone, and form, can be carried through all design professions. So there’s a definite overlap in what we do.

In hindsight, it was obvious Berthier would want committee approval before completion. This desire, and my inability at the time to anticipate or ask about it, meant the project time frame would be significantly lengthened as a result of internal committee meetings.

But to counter the broader timescale, the committee involvement also meant I could draw upon the design experience of Berthier’s team to produce the strongest possible outcome. Ultimately, the committee proved to be a great asset throughout the working relationship.

With every client since Berthier, I’ve made a point of asking at the outset, “Who’ll be involved in the decision-making?” Had I done this with Berthier, I would’ve lengthened the expected project time frame to accommodate those internal meetings, which would’ve gone a long way toward keeping deadline expectations in check.

Ensuring you get to present your ideas to the committee rather than to your point of contact is an ongoing process—a series of steps to adhere to from the beginning of the project to make sure that when the time comes, you’re presenting your ideas directly to those with the final say.

Blair Enns, founder of Win Without Pitching, a consulting firm that helps studios work more effectively with their clients, believes that designers can improve the quality of their work and avoid the counterproductive side of “design by committee” by adhering to four basic rules:

• Conspire with your point of contact

• Avoid intermediation

• Take control

• Keep the committee involved

Blair is a speaker, author, and teacher who has worked with design firms, advertising agencies, and public relations agencies around the world to help them move away from high-cost, low-integrity, pitch-based business strategies. Instead, he advocates for a model in which the agency commands the high ground in the relationship and shapes how its services are bought and sold. His advice has helped me create smoother, more effective relationships with my clients.

All that might sound a little cryptic, so the next few sections of this chapter will go into the details of these four principles, with a few personal anecdotes.

#1: Conspire to help

An introduction to any client usually begins with a single point of contact. For example, maybe you’re dealing with a nonprofit organization where the committee is often a board. In this case, your contact is likely to be an employee. Or maybe your client is an architectural studio where the committee is composed of the partners in the firm. Your initial contact could be an office manager or marketing director who isn’t a partner or even an architect.

According to Blair, this contact will probably be just as anxious as you are about the potential pitfalls of committee-based decision-making. In such cases, empathy is a powerful trait.

By placing yourself in your contact’s shoes, you’ll likely see that presenting the design ideas to the committee as a whole is at the top of her priority list, too, and that any help you can offer will be greatly appreciated.

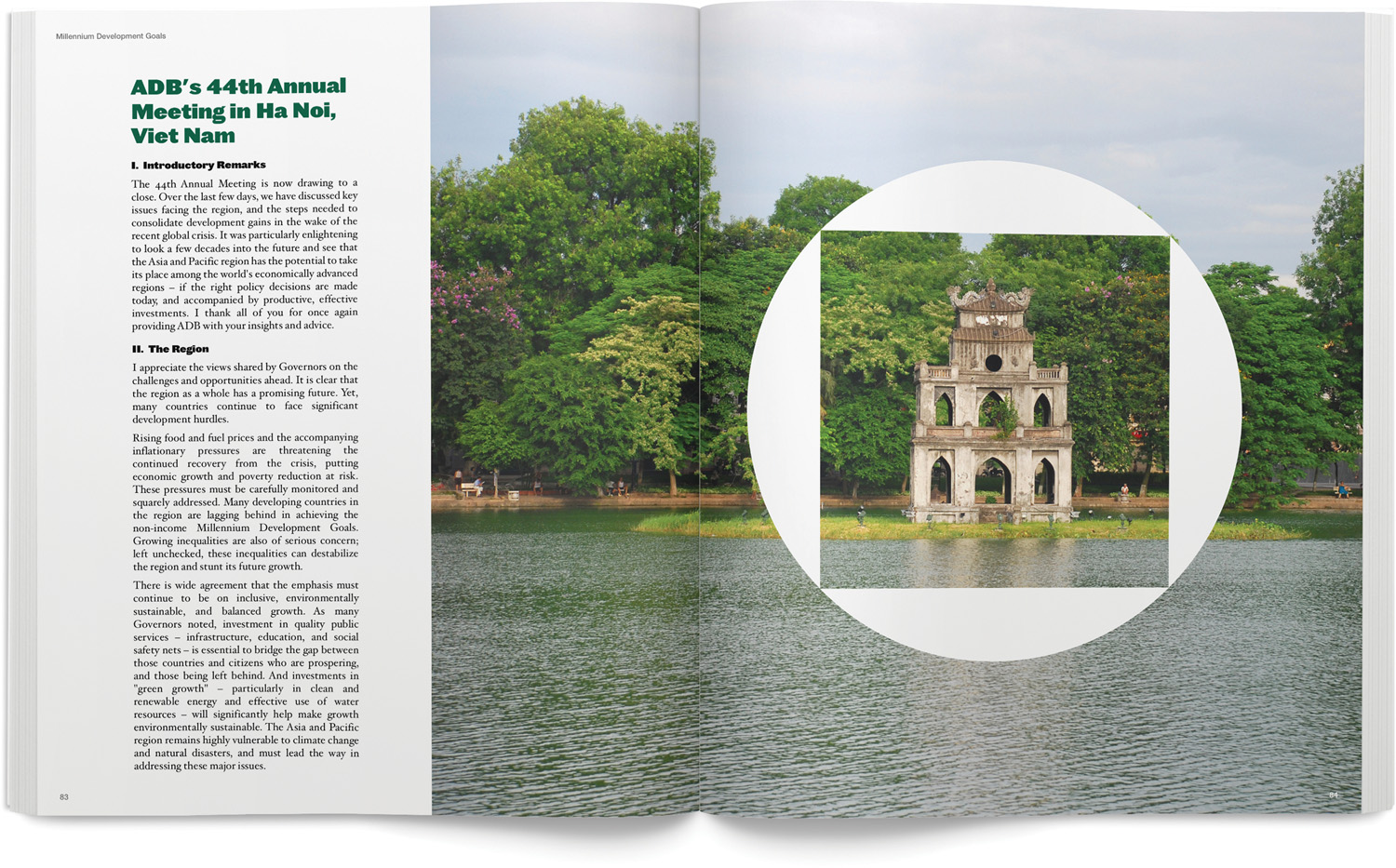

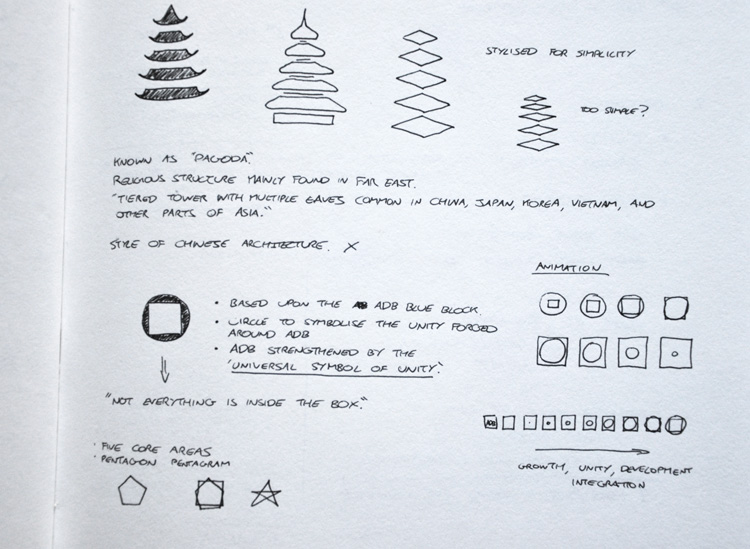

A past project of mine (mentioned briefly in the last chapter) involved creating a symbol to represent the Asian Development Bank’s Annual Meeting—an event that’s held each year in a different ADB-member country and attended by more than 3,000 people. My initial point of contact was an employee in ADB’s Department of External Relations. He had initially been tasked with writing a design brief, engaging with five different designers, and collecting quotes to submit to the office of the secretary. Once I was chosen for the job, an important step was to take part in a conference call with the four decision-makers in order to clarify expectations and set a plan for moving forward (my client was in the Philippines and I was in Northern Ireland, so talking on the phone was the most appropriate way to communicate). Due to their schedules, it wasn’t possible for me to deal directly with the committee on a daily basis, so when they were happy with the process I described, and after they answered all my questions, my point of contact and I worked together to ensure the ideas to be presented were given the best possible chance of gaining committee consensus.

We helped each other.

From the beginning, make it very clear you’re there to help and that you’re well versed in helping people like your contact achieve approval from the broader team. Together, the two of you can conspire to ultimately win the confidence of the committee.

#2: Avoid intermediation

The first principle—conspire to help—is also part of the second: avoid intermediation at all costs at presentation time.

Think about it. You may have been hired as an expert, but if your designs are presented by your contact—a subordinate of the committee—they could be perceived with lesser value. And what if there are objections to your design decisions? How effectively can these be addressed by your contact?

You also have no idea what your contact’s relationship might be with the committee or whether any personal issues exist that could interfere with the committee’s acceptance of your ideas. The presence of “office politics” within the committee itself might inhibit members’ acceptance of your designs—issues that your contact is powerless to subdue.

Having someone else explain your design decisions places an unnecessary barrier between you and the decision-maker. Remove anything that can hinder the process at this delicate stage.

Sometimes that’s easier said than done. One project from early in my career was particularly challenging in this respect. My client was based in Greece, and my point of contact was one of two partners, a husband and wife team, with both partners having an equal say over the final design.

The issue was that while the husband spoke fluent English, his wife didn’t. I can’t speak Greek, so I knew this meant that my design explanations held the potential to be lost in translation, with the husband acting as mediator, but I wasn’t sure how to work around it. I ended up presenting to the husband, and at a later time, which in some instances was a few days later, he presented to his wife. Not only was the translation a potential hindrance, but the delay between presentations led to vital reasoning being omitted or forgotten.

At the time, I didn’t know how damaging this could be to the outcome. As it turned out, my client rejected all four of my initial ideas in favor of a much more generic solution that the two partners created between them. Neither partner had any design experience, and as much as I tried to persuade them against their choice, it was too late. I had already lost control of the process.

Even when all the decision-makers speak your language, getting your point of contact to agree that you’re the only one who can present to the committee can sometimes be a challenge. That’s where principle #1 comes into play. You’ve already positioned yourself as someone who’s there to help—someone who can aid in the task of gaining committee approval. To further your cause, you might also offer to deliver a dry run of your presentation to your contact before the committee gets a chance to see it, so that your contact is more comfortable about your intentions.

Blair Enns advises that if all else fails when trying to convince your contact, use the phrase “studio policy.” Tell her it’s your studio’s policy that designers with your firm must be the ones to present design ideas to decision-makers.

“You’ll be surprised how often resistance melts away when they hear these words,” said Blair.

#3: Take control

Once you’ve secured the goal of meeting with the committee, what’s critical is that you control the meeting from the very beginning. Keeping a tight rein on proceedings will help immeasurably in securing approval for your ideas.

But before you unveil your designs, it’s worth remembering that months could have passed since the committee discussed the details of the design brief. CEOs, directors, and business owners all have a lot of other concerns, so by jogging their memories, you’ll ensure that everyone’s in tune with why time and money are being invested in brand identity.

Briefly state the project background—why a new or refined identity is needed, what the goals for a new design are, and how having a new identity will actually help the company to increase profits. You can judge the depth of detail you should go into by the amount of time that has passed since the briefing stage.

The more time that has passed, the more detail you’ll want to provide. But don’t go overboard. It’s just a refresher, not an essay, and you have an audience of very busy people. A couple of minutes talking should suffice.

As clear as you think your ideas are, a little design jargon might slip into your language here and there. This can quickly lose your client’s train of thought, so remember: you’re not talking to another designer. Make your points clearly, without jargon, and keep them related to the original design brief.

Outline the ground rules

Once you’ve brought everyone up to speed, maintain control of the presentation by outlining a few ground rules.

Committee members will often see the showcasing of design ideas as an invitation to make their own design decisions. It’s your task to remind everyone that while their input is critical, they should resist the temptation to start doing your job for you. You’re the expert, and if the discussion devolves into them telling you what colors or fonts to use, the identity will inevitably be weakened.

Let them know that what you need from them is strategic input and executional freedom. Something like, “So let me know if you think the idea isn’t meeting our agreed-upon strategy, but don’t worry about figuring out and suggesting how to fix it. That’s what you’re paying me to do.”

You could even share what constitutes good feedback with the committee, perhaps something like this, for example: “It’s helpful when you tell me if you think a purple is too weak for an organization trying to present an image of strength, or that a typeface is too old-fashioned. Letting me know these thoughts is critical to the project’s success. But stop short of saying ‘Make the blue darker’ or ‘Try using Tungsten Condensed.’ You have to trust that I can find the right design solution based on your feedback. Otherwise, we’ll risk diluting the strength of the identity because too many non-designers are trying to design.”

You might also find that many committees contain one strong personality in the group—a person who holds more influence than the others simply because he’s more outspoken. This can create awkward dynamics and undesirable outcomes. However, as an outsider merely enforcing protocol, you have the ability to bring balance back to the committee when insiders can’t. Don’t underestimate the value of this outside facilitation. Take control and hold your ground.

Don’t wait until the presentation

Of course, if you haven’t kept some level of control from the beginning of the process—way before the presentation—you’ll probably have a difficult time keeping control at this point. The relationship you have with your client throughout the process is vital for the acceptance of your ideas.

“Early in your first interaction with the committee you have the choice of establishing the relationship as either one of patient (client) and practitioner (studio) or one of customer and order-taker,” said Blair. “You will be viewed as a doctor or a waiter, depending on the degree to which you take control of the situation.”

He’s right. It’s an easy trap to fall into—finding yourself as an order-taker. During my earliest projects it happened far too often. The client would tell me to use this typeface, or that color, and I’d say, “No problem. Expect those changes by tomorrow.” In such instances, the client was doing my job, only without the benefit of my design education and experience. That’s hardly helpful when creating iconic brand identities.

If I’d have known the advice in this chapter when I was starting out, I’m positive it would’ve saved me plenty of headaches and a lot of continuous back-and-forth on the latest whim of my client’s taste.

#4: Keep the committee involved

There’s that old saying, “Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.” Whether you consider the committee a friend or foe, you can help to close the deal by defining the role of the committee in the client-studio relationship very early in the process. Part of your definition should make clear at which points in the process input will be helpful, and when it won’t.

It’s highly reassuring to any client that the committee is indeed part of the process and that its feedback is vital to the project’s success. The committee will be far easier to work with when it’s included in development along the way—especially on the strategic issues that characterize the early part of the relationship—rather than apprised of it afterward. You just need to set the ground rules for how and when that feedback comes in.

In 2004 I was hired to create a logo for a startup landscaping company. For the first couple of weeks, and after a few face-to-face meetings, the design process was running smoothly, but when it was time to present my ideas, things turned sour. What I didn’t know was that even before I was hired, the committee already had a firm grasp of the design they wanted to see. They wanted me to bring it to life rather than create a visual from my own research and brainstorming. The only hitch was that they didn’t tell me. Instead, they considered the possibility that I might design something they liked even better and so decided to keep their preference to themselves.

I strongly believed that the ideas I presented were more relevant to my client’s audience, but the reality was the committee members had already attached themselves to their own idea. So the weeks I spent on research, brainstorming, sketching, and conceptualizing wasn’t important to them.

It was one of those early setbacks in self-employment where if I’d been more thorough about setting ground rules, I could’ve saved a month of misused time. I should have said something like, “With your help, I’ll create a number of possible design directions that are ideally suited to your potential customers. Once the different ideas have been presented, we can choose the most effective option and either move forward with it or tweak it a little after your feedback.”

Of course, I also could have asked in the initial meeting if my client had any preconceived design ideas. Regretfully, I didn’t. Your goal at each meeting is to attain approval and consensus among the committee. What you don’t need is to have worked through a solid strategy for your final ideas only to hear concerns about the underlying message. Strategy is one of the first aspects you and the committee should reach agreement on, and revisiting it at this late stage is extremely counterproductive.

Now that you know Blair Enns’ four principles for ensuring the presentation goes the way you hope, let’s look at scheduling.

Under-promise, over-deliver

Being accurate in hitting your deadlines is key to a healthy client relationship. Think of the last time you bought a product online. Didn’t you want to know when to expect delivery? Design clients are no different. They depend on you delivering when you say you will. So when you’re unsure how long a task will take to complete, always give the client an estimate that’s longer than the amount of time you’re guessing it will take. Why? Because unexpected setbacks can crop up at any time. Think of the computer you work on each day, the software you use on a regular basis, the Internet connection you pay for, the electricity that powers your office, and your good health.

All of these necessities are by no means guaranteed, and it almost goes without saying you’ll have a computer problem at one time or another that will affect your productivity. Even if your equipment stays up and running, a person can let you down, and even the most independent designer relies on others to get the job done.

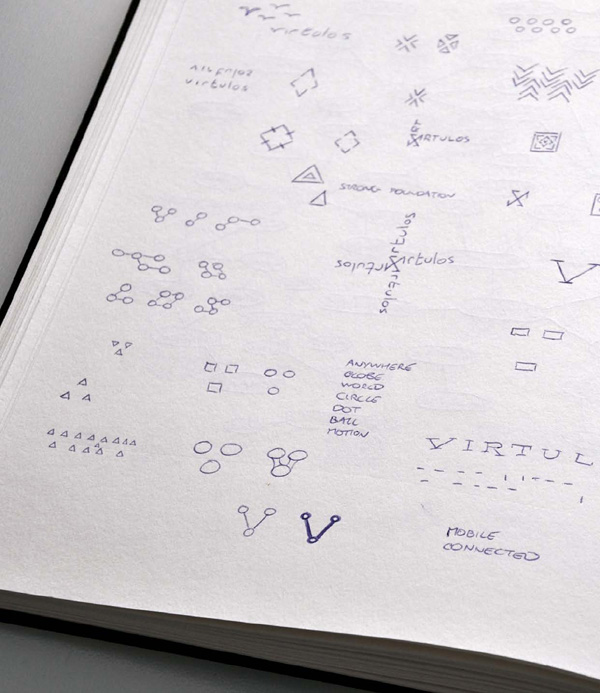

When Virtulos hired me in 2013, I knew I’d be traveling for 10 days midway through the project. By letting my client know about this time away at the start of the project, I was able to explain why the design process would take longer than normal.

Because my client was aware of the extended time frame, he was happy to accommodate my break from the office. So factor the worst into your delivery schedule, and then impress your client by delivering ahead of time when things go smoothly.

Typeface customizations

The design idea was that Virtulos helps its customers grow. The visual incline represents this growth.

Swallow a little pride

It’s important to reiterate that the design process always includes more than one party. And where discussions of any kind take place, you should always be prepared to swallow some pride and listen to the feedback. Of course, you should also expect your client to stick to the ground rules laid out earlier in this chapter. If not, you might need to remind the committee of those rules now and then.

Clients often make suggestions that you might initially disagree with. Here’s a case in point: I produced two appropriate ideas for TalkTo—a texting app that helps you get answers from local businesses—and while the committee liked my preferred option, they thought it was pushing boundaries too far for representing the company’s simple approach. In retrospect, I realize their choice was more suitable.

TalkTo

The more dynamic wordmark I preferred due to the adaptability of the double line idea and how it pulled marketing collateral together.

TalkTo

The chosen—and ultimately more appropriate direction—a relatively straightforward customization of Gotham Rounded.

Even when everything inside of you is saying “no” to your client’s feedback, it always pays to listen well and keep an open mind.

In another example, when I contracted with Yellow Pages on the redesign of its “walking fingers” symbol, my job was to retain the fingers but make them look different from before.

Some members of the committee were convinced that adding a dart alongside the fingers would improve things. (Yellow Pages was using a dart as a symbol on its website at the time.) I was certain it wouldn’t.

My client wasn’t aware of the “focus on one thing” principle that I discuss in Chapter 3, so I realized that committee members needed to see for themselves that adding the dart would infuse the design with too many elements.

Rather than getting defensive, I delivered on the request. But I also coupled the idea with another that I believed was a much better improvement, and explained why when I presented it.

Once the results were compared, it was easier for the committee to deem its design idea unsuitable. Clients are much less likely to resist your ideas moving forward if they’ve seen how their own strategic interpretation pans out.

Yellow Pages symbol refinement

Before (left), and after (right). The option that included a dart isn’t even worth showing you. That’s how inappropriate it was.

Remember during your presentation that what you’re selling at this stage is the idea behind your best designs. Remind your client as often as necessary to focus on just the idea—the story behind the design concept—not the intricacies of the mark or the particular choice of typeface. These lesser details can be ironed out when a single direction has been agreed upon. Otherwise, you could end up supplying revisions for more than one direction, which is an unnecessary cost for both parties.

Keep in mind, however, that things won’t always go your way. Throughout my years of self-employment, I’ve presented brand identity projects to more than 100 clients. Two or three of my earliest presentations were so unsuccessful that they caused a stalemate in the process, and both my client and I lost out. Yet I’ve learned just as much, if not more, about the client relationship from those debacles as I have from the successful projects.