Chapter four. Laying the groundwork

At some point in the future, you might find yourself giving your client a lesson about design—perhaps about typography or print quality, for example. But first it’s important that you learn all you can about your client. Without knowing specific details of your client’s business, his reasons for seeking a brand identity, and his expectations of the process and final design, you can’t possibly be successful with the project.

Gathering this info needs a significant investment of time, and more than a little patience, especially when what you prefer to do is to get started on the design work. But if you cut back on the time and attention this early stage needs and jump straight onto the sketchpad, you risk completely missing your client’s mark.

Calming those nerves

At the onset of just about any design project, you or your client, or perhaps both of you, will likely be feeling some anxiety. That’s because, as any designer with a bit of experience can attest, the client-designer relationship doesn’t always run smoothly.

For your part, you need to be careful choosing clients, in the same way that clients often choose from a number of designers.

I get emails like this now and again:

“I need a logo. I know exactly what I want. I just need a designer to make it happen.”

On the contrary, that person doesn’t need a designer. She is the designer. She needs someone who knows how to use computer software. She can save herself money by finding that person instead.

Always remember that you’re being hired because you’re the expert. The client should not assume the role of telling you what to do. She should be comfortable simply letting you do what you do best—creating iconic brand identities.

If you feel uneasy in any way about the relationship, you should definitely find a way to discuss it with the client. There’s nothing like healthy dialogue to get a clear sense of what is expected, both on your part and on the part of your client.

Most clients will be anxious about the process of having a brand identity created for their business. Many will see ideas as a risk, and not as a way to secure their mortgage. So the more in-depth your initial discussions, the more at ease you will make your clients. It may be that it’s their first time working on an identity project, and it’s up to you to show them how smoothly the process can flow.

Brief, not abrupt

Understanding your client’s motivations involves a lot more than simply setting minds at ease, however. You’re not a mind reader, so a series of specific questions and answers about your client’s needs and desires is the first order of business. You then turn this information into a design brief that reflects the expectations of both you and your client for the project.

The design brief plays a pivotal role in guiding you and the client to an effective outcome. There might be stumbling blocks that crop up along the way—your client may disagree with a decision you’ve made, for instance. It’s at points like this when you can return to the details of the brief to back up your stance.

That’s not to say you won’t make design changes as a result of a disagreement—you want to please your client, after all. But the design brief exists to provide both of you with concrete reasons for making decisions throughout the process.

There are several ways you might obtain the information you need from your client: in person, by telephone, video chat, or by email. I find that with many of my clients, it’s useful to pose questions in the form of a digital questionnaire or email. With others, more face-to-face time might be necessary. What matters most is that you’re able to extract as much relevant information as possible, and at the beginning of the project.

Gathering preliminary information

You’ll want to ask your potential client the following basic information before moving on to some in-depth questions:

Your name

Company name

Telephone number

Mailing address

Web address

Years in operation

Your role in the company

More detail

The crux of a healthy design brief lies in the questions you pose. Getting the answers isn’t difficult. You just need to ask.

Here are a few suggested questions to use as a starting point. Keep in mind, however, as you form your own list, that the needs of each industry and every company vary.

Summarize the business

What do you sell?

Who do you sell to?

How much does it cost?

Summarize the project

What are your goals for a new identity design?

What specific design deliverables do you want?

Who will be working on this project from your end? Will any additional outside partners or agencies be involved, and if so, how?

What is motivating you or enabling you to do this project now?

When does my work need to be finished, and what is driving that?

What are you worried about? What do you imagine going wrong?

Is there anything about your company that might make this project easier or harder in certain ways?

How many designers are you talking to and when do you expect to make a decision?

A quick note on the decision-maker

One of those questions concerns who is working on the project from the client end. This is important because you want to know if you’re dealing directly with the decision-maker throughout the project. Dealing with the decision-maker—in other words, the person or committee who has the final say over the company’s brand identity—isn’t as critical during the information-gathering stage as it is when you present your ideas. We’ll talk more about this in Chapter 8.

When working with larger organizations, it’s more likely that your point of contact is an employee rather than the CEO. This person will help you to gather all the necessary information for the design brief. Later in the process, he’ll be likely to introduce you to the decision-maker or a committee. But for now, the focus is on information gathering.

Give your client time and space

These questions are enough to get you started. You’ll probably have more to add, given that every industry has its own specific requirements, quirks, and expectations.

As you pose your set of questions, don’t rush the client to answer them. We all appreciate some space to consider answers in our own time, and you’ll end up gaining more insight, too. Welcome the opportunity to answer seemingly off-topic questions, because at this stage every detail helps.

But maintain the focus

In addition, don’t allow your client to confuse this as a chance to dictate terms; instead it’s an opportunity to really focus on the project and on the benefits the outcome will achieve. It’s precisely this level of focus that will provide you with all of the information you need to do your job.

The client’s answers are likely to make you ask follow-up questions, as well as prompt some ongoing discussion about design ideas.

Study time

Once you’ve gathered the necessary preliminary information, spend some time very carefully reviewing it.

What are your client’s concerns?

What does the company want to play up?

What is it truly selling?

And how does the company want to present itself in the market? Identities that are pretty and stylish may win awards, but they don’t always win marketshare.

The next step of the information-gathering stage involves conducting your own field research. Learn as much as you can about the company, its history, its current brand identity, and the effect it has had on market perception. And don’t forget to review any identities it has used in the past. These additional insights are critical. You also need to focus on how your client’s competitors have branded themselves, picking up on any weaknesses you perceive and using them to your advantage in your design. After all, if your client is to win, there needs to be a loser.

Assembling the design brief

Documenting the information can be a matter of taking notes during a meeting (having a minute-taker present can be a big help), recording telephone conversations, editing an email back-and-forth, and stripping the chat down to just the most important parts. Did I mention that designers need to be editors, too?

It’s wise to create a succinct, easily accessed, and easily shared document that you or your client can refer to at any time. You’ll want to send a copy to those involved in the project. And keep a copy at hand to use in follow-up meetings.

For your part, you want to use the brief to help keep your designs focused. I’m sure that I’m not the only designer to have entertained some pretty far-fetched ideas every now and then. Relevancy—one of the elements we’ve already discussed—is key, and your brief can help you stay on track.

Let’s look at a few instances in which designers extracted critical information from their clients and then used it to create effective results.

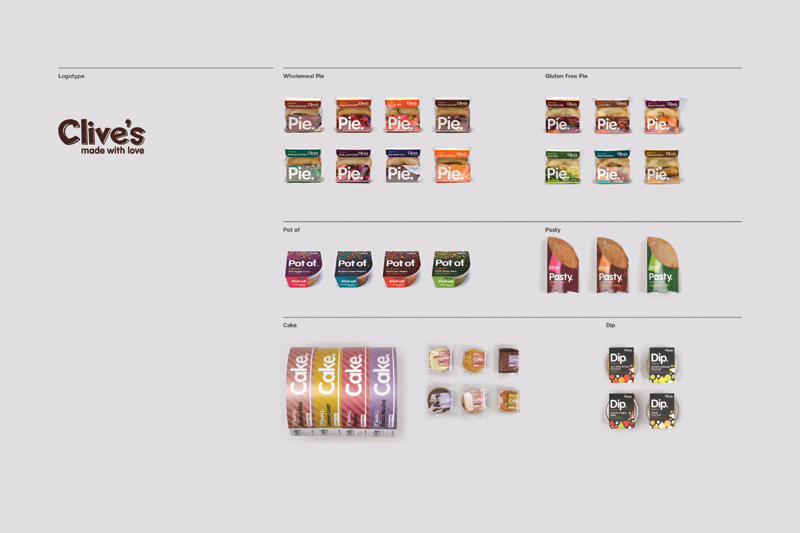

A mission and some objectives hold the key

Clive’s is a specialist organic bakery set in the heart of Devon, England. Since 1986, the company has been making pies stuffed to bursting point with unique fillings inspired by culinary traditions from around the world.

In 2005, Clive’s asked English studio Believe in to rebrand the bakery (at the time the company was named Buckfast Organic Bakery) because its existing identity had become dated, inconsistent, and uninspiring. The brand was also failing to communicate the vibrancy behind the company and its unique range of vegetarian and gluten-free pies, cakes, and pastries.

Believe in got the creative process rolling by creating a design brief that included a description of Clive’s mission, as well as the project’s objectives.

The mission was to contemporize the bakery’s image and emphasize the uniqueness of the product. The new brand objectives aimed to communicate the dynamic personality of the company; highlight the organic nature of the products and their homemade quality; convey the healthy, yet fun and tasty recipes; and introduce Clive’s to a new generation of health-conscious, brand-aware consumers.

Clive’s

By Believe in, 2005, with updated packaging in 2014

“We usually show up to three different design routes for projects like this, with each route supported by a clear rationale, and the process often includes a preferred solution, again with clear reasons to support the recommendation.” Blair Thomson, creative director, Believe in

Believe in’s solution was to create a logo that combined a hand-drawn typeface with clean modern type, communicating the forward-thinking values of the company, together with the homemade qualities of the products.

The strapline “made with love” emphasizes the handmade, healthy, natural, and organic quality of Clive’s products.

Clive’s wanted the new identity applied to its packaging, marketing materials, website, and company vehicles. Believe in created a new design for the packaging that combined the logo with “Pot of” typography and colorful graphics.

Large, distinctive typography, bright colors, and bold photography focusing on fresh organic ingredients make the brand easily identifiable, giving it a contemporary, confident appearance that appeals to a much wider audience than before.

Clive’s had a 43 percent increase in product sales during the first 18 months after the new identity was launched.

Field research making a difference

When Federal Express Corporation invented the overnight shipping business in 1973, the market was one-dimensional: one country (USA), one package type (letter), and one delivery time (10:30 a.m.). By 1992, the company had added new services (end of next business day and two-day economy) and was shipping packages and freight to 186 countries. But by then, a host of competitors had emerged and created the perception of a commodity industry driven by price. As the most expensive service, Federal Express was losing market share.

Federal Express Corporation

An earlier, less distinctive design.

The company clearly needed to better communicate its broad service offering and reaffirm its position as the industry leader. It hired global design firm Landor in 1994 to create a new direction that would help reposition the delivery corporation.

For Landor, market research was key in producing an enduring and effective design. Landor and Federal Express assigned both of their internal research groups to collaborate for a nine-month global research study. The study revealed that businesses and consumers were unaware of the international scope and full-service capabilities offered by FedEx, believing that the company shipped only overnight and only within the United States.

Landor conducted additional research about the Federal Express name itself. It found that many people negatively associated the word “federal” with government and bureaucracy, and the word “express” was overused. In the United States alone, over 900 company names were employing this word.

On a more upbeat note for Federal Express, the research also revealed that businesses and consumers had been shortening the company’s name and turning it into a generic verb—as in “I need to FedEx a package,” regardless of which shipper was being used. In addition, research questions posed to the company’s target audience confirmed that the shortened form of the name, “FedEx,” conveyed a greater sense of speed, technology, and innovation than the formal name.

Landor advised Federal Express senior management to adopt “FedEx” as its communicative name—to better suggest the breadth of its services—while retaining “Federal Express Corporation” as the full legal name of the organization.

Over 300 designs were created in the exploratory phase, ranging from evolutionary (developed from the original) to revolutionary (altogether different ideas).

FedEx logo options

The new logo and abbreviated company name that Landor came up with allows for greater consistency and impact in different applications, ranging from packages and drop boxes to vehicles, aircraft, customer service centers, and uniforms.

Landor and FedEx spent a great deal of time and energy researching the marketplace, discovering how the Federal Express brand was perceived, where they needed to improve, and how to do it. This is a fine example of how in-depth preparation led to an iconic solution.

FedEx

By Lindon Leader (while at Landor), 1994

Bringing the details to life

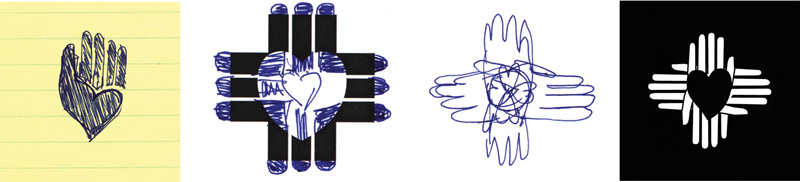

Designer Maggie Macnab was asked to create a new logo for the Heart Hospital of New Mexico. A teacher who has taught brand identity at the University of New Mexico for more than 10 years and a past president of the Communication Artists of New Mexico, Maggie felt it was vital to clarify her client’s expectations from the very outset.

During the information-gathering stage, Maggie had meetings with the hospital design committee (comprising doctors from merging small practices and the funding insurance company). She asked what was required from the brand project and was given these criteria:

• The identity must have a New Mexico “look and feel.”

• It must (obviously) be directly related to cardiology.

• The patients need to know that they’re in very good hands.

Broader research on New Mexico told Maggie that the Zia symbol was being used as the state logo, as it had been for more than 100 years. The Zia are an indigenous tribe centered at Zia Pueblo, an Indian reservation in New Mexico. They are known for their pottery and the use of the Zia emblem. Zia Pueblo claims this design; it’s a prevalent indigenous pictograph found in the New Mexico area.

The Zia sun symbol

“I knew there was something about all three project criteria in the Zia symbol, so I encouraged the doctors to ask for an audience with the elders at Zia Pueblo to request the use of their identifying mark,” said Maggie. “The Zia is an ancient and sacred design, and I was well aware of Zia Pueblo’s issue with people randomly slapping it on the side of any old work truck as an identity, which happens often in New Mexico.”

After receiving permission from the elders, and after dozens of experimental iterations and sketches, Maggie integrated the palm of a hand with a heart shape, and the Zia became the mark symbolizing both New Mexico and the ministering of hands-on care.

Heart Hospital of New Mexico

By Maggie Macnab, 1998

“I’ve always been a symbolist and nature-lover, and both are essential in an effective logo. Symbols are derived of nature, and this knowledge is common to every human on earth, although it is not discussed much, let alone taught in most design classes.” Maggie Macnab

Maggie’s thoroughness during the initial project stages not only convinced Zia Pueblo to grant the use of the Zia symbol, but they also blessed the hospital grounds and danced at the groundbreaking ceremony—excellent PR for the fledgling heart hospital.

“It’s always a good idea to be sensitive to things like this,” added Maggie. “Not only are you doing the right thing by showing common courtesy, but respecting traditions and differences can bring great and unexpected things together—very important for collective acceptance.”

Culling the adjectives supplied by the client

Something you might want to ask your clients is what words they want people to associate with their brand identities. This can be fruitful information for a designer.

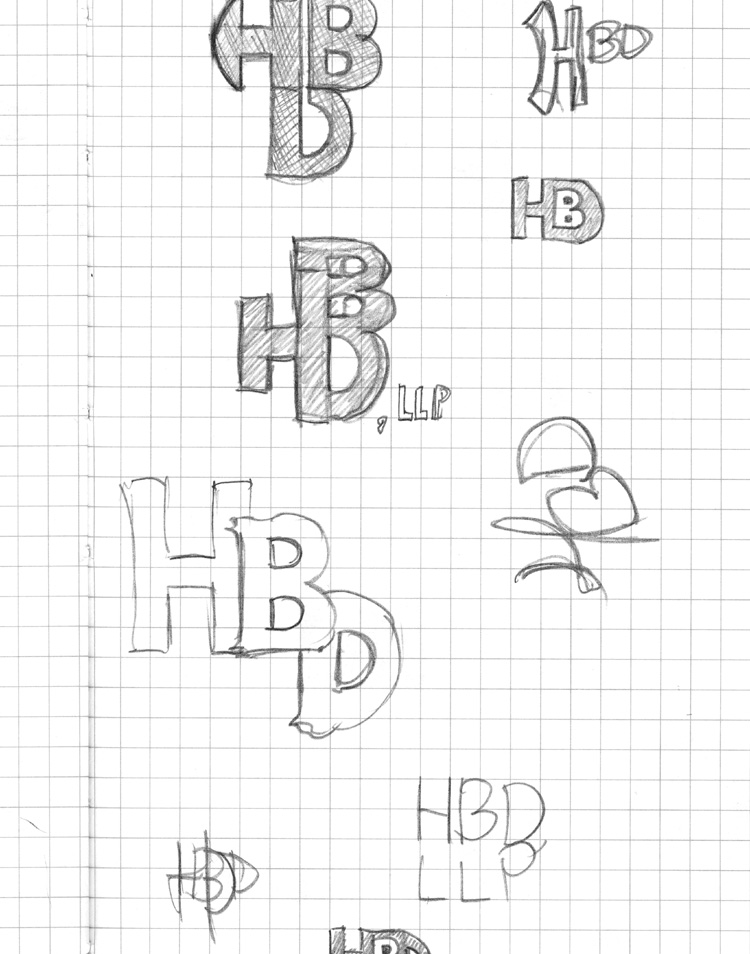

Executives at Harned, Bachert & Denton (HBD), a law firm in Kentucky, felt that HBD’s identity didn’t effectively portray the experience, history, and integrity that the firm had built over nearly 20 years. They wanted a design that distinguished them as a professional and unified group of ethical attorneys.

The old HBD monogram lacked any sense of design style and was very easy to forget, so designer Stephen Lee Ogden was given the task of creating an effective redesign. Meetings, chats, and email between client and design team helped Stephen learn what was needed for the new identity.

Harned, Bachert, & Denton

Old logo

The following words were specified as the ideal fit: professional, ethical, strong, competent, unified, relevant, experienced, detail-oriented, and approachable. Stephen relied heavily on these adjectives to help him shape the new icon.

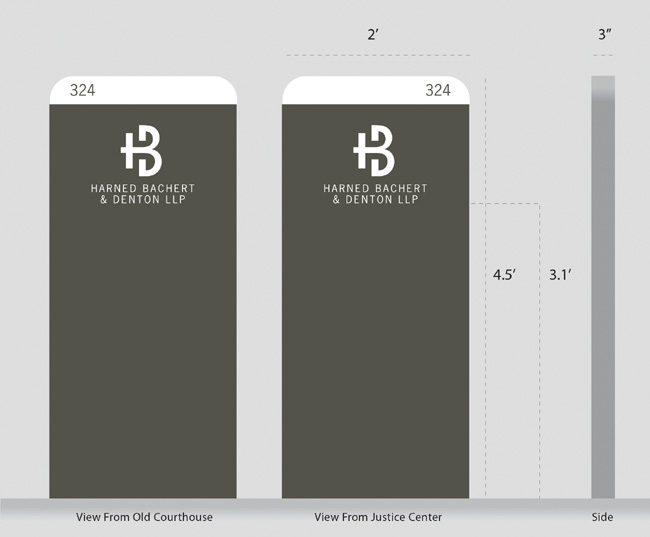

The rationale behind the icon was that the simple, bold shape would come to symbolize a unified firm. All of the firm’s partners bought into the idea.

Harned, Bachert, & Denton

By Stephen Lee Ogden, during employment at Earnhart+Friends of Bowling Green, Kentucky, 2007

When you take the time up front to really get to know your client and the related industry, you not only stand a much greater chance of delivering a design you respect and they love, but you also put yourself in a strong position for advising them about designs at some point down the road. Once clients see what you’re made of, they’ll happily send more work your way.