“The death is my life, the strength becomes my weakness, the journey has ended.”

—Dated Betabanes, 1173, 95 seconds pre-death. Subject: a scholar of some minor renown. Sample collected secondhand. Considered questionable.

“That is why, Father,” Adolin said, “you absolutely cannot abdicate to me, no matter what we discover with the visions.”

“Is that so?” Dalinar asked, smiling to himself.

“Yes.”

“Very well, you’ve convinced me.”

Adolin stopped dead in the hallway. The two of them were on their way to Dalinar’s chambers. Dalinar turned and looked back at the younger man. “Really?” Adolin asked. “I mean, I actually won an argument with you?”

“Yes,” Dalinar said. “Your points are valid.” He didn’t add that he’d come to the decision on his own. “No matter what, I will stay. I can’t leave this fight now.”

Adolin smiled broadly.

“But,” Dalinar said, raising a finger. “I have a requirement. I will draft an order—notarized by the highest of my scribes and witnessed by Elhokar— that gives you the right to depose me, should I grow too mentally unstable. We won’t let the other camps know of it, but I will not risk letting myself grow so crazy that it’s impossible to remove me.”

“All right,” Adolin said, walking up to Dalinar. They were alone in the hallway. “I can accept that. Assuming you don’t tell Sadeas about it. I still don’t trust him.”

“I’m not asking you to trust him,” Dalinar said pushing the door open to his chambers. “You just need to believe that he is capable of changing. Sadeas was once a friend, and I think he can be again.”

The cool stones of the Soulcast chamber seemed to hold the chill of the spring weather. It continued to refuse to slip into summer, but at least it hadn’t slid into winter either. Elthebar promised that it would not do so—but, then, the stormwarden’s promises were always filled with caveats. The Almighty’s will was mysterious, and the signs couldn’t always be trusted.

He accepted stormwardens now, though when they’d first grown popular, he’d rejected their aid. No man should try to know the future, nor lay claim to it, for it belonged only to the Almighty himself. And Dalinar wondered how stormwardens could do their research without reading. They claimed they didn’t, but he’d seen their books filled with glyphs. Glyphs. They weren’t meant to be used in books; they were pictures. A man who had never seen one before could still understand what one meant, based on its shape. That made interpreting glyphs different from reading.

Stormwardens did a lot of things that made people uncomfortable. Unfortunately, they were just so useful. Knowing when a highstorm might strike, well, that was just too tempting an advantage. Even though stormwardens were frequently wrong, they were more often right.

Renarin knelt beside the hearth, inspecting the fabrial that had been installed there to warm the room. Navani had already arrived. She sat at Dalinar’s elevated writing desk, scribbling a letter; she waved a distracted greeting with her reed as Dalinar entered. She wore the fabrial he had seen her displaying at the feast a few weeks back; the multilegged contraption was attached to her shoulder, gripping the cloth of her violet dress.

“I don’t know, Father,” Adolin said, closing the door. Apparently he was still thinking about Sadeas. “I don’t care if he’s listening to The Way of Kings. He’s just doing it to make you look less closely at the plateau assaults so that his clerks can arrange his cut of the gemhearts more favorably. He’s manipulating you.”

Dalinar shrugged. “Gemhearts are secondary, son. If I can reforge an alliance with him, then it’s worth nearly any cost. In a way, I’m the one manipulating him.”

Adolin sighed. “Very well. But I’m still going to keep a hand on my money pouch when he’s near.”

“Just try not to insult him,” Dalinar said. “Oh, and something else. I would like you to take extra care with the King’s Guard. If there are soldiers we know for certain are loyal to me, put those in charge of guarding Elhokar’s rooms. His words about a conspiracy have me worried.”

“Surely you don’t give them credence,” Adolin said.

“Something odd did happen with his armor. This whole mess stinks like cremslime. Perhaps it will turn out to be nothing. For now, humor me.”

“I have to note,” Navani said, “that I didn’t much care for Sadeas back when you, he, and Gavilar were friends.” She finished her letter with a flourish.

“He’s not behind the attacks on the king,” Dalinar said.

“How can you be certain?” Navani asked.

“Because it’s not his way,” Dalinar said. “Sadeas never wanted the title of king. Being highprince gives him plenty of power, but leaves him with someone to take the blame for large-scale mistakes.” Dalinar shook his head. “He never tried to seize the throne from Gavilar, and he’s even better positioned with Elhokar.”

“Because my son’s a weakling,” Navani said. It wasn’t an accusation.

“He’s not weak,” Dalinar said, “He’s inexperienced. But yes, that does make the situation ideal for Sadeas. He’s telling the truth—he asked to be Highprince of Information because he wants very badly to find out who is trying to kill Elhokar.”

“Mashala,” Renarin said, using the formal term for aunt. “That fabrial on your shoulder, what does it do?”

Navani looked down at the device with a sly smile. Dalinar could see she’d been hoping one of them would ask. Dalinar sat down; the highstorm would be coming soon.

“Oh, this? It’s a type of painrial. Here, let me show you.” She reached up with her safehand, pushing a clip that released the clawlike legs. She held it up. “Do you have any aches, dear? A stubbed toe, perhaps, or a scrape?”

Renarin shook his head.

“I pulled a muscle in my hand during dueling practice earlier,” Adolin said. “It’s not bad, but it does ache.”

“Come over here,” Navani said. Dalinar smiled fondly—Navani was always at her most genuine when playing with new fabrials. It was one of the few times when one got to see her without any pretense. This wasn’t Navani the king’s mother or Navani the political schemer. This was Navani the excited engineer.

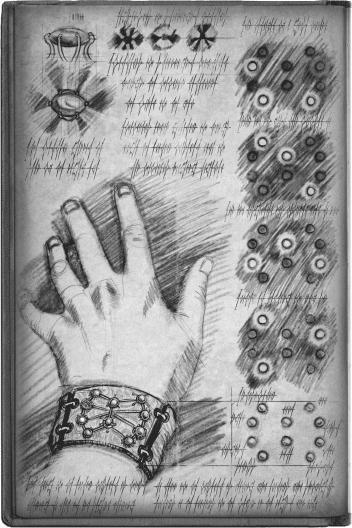

“The artifabrian community is doing some amazing things,” Navani said as Adolin proffered his hand. “I’m particularly proud of this little device, as I had a hand in its construction.” She clipped it onto Adolin’s hand, wrapping the clawlike legs around the palm and locking them into place.

Adolin raised his hand, turning it around. “The pain is gone.”

“But you can still feel, correct?” Navani said in a self-satisfied way.

Adolin prodded his palm with the fingers of his other hand. “The hand isn’t numb at all.”

Renarin watched with keen interest, bespectacled eyes curious, intense. If only the lad could be persuaded to become an ardent. He could be an engineer then, if he wanted. And yet he refused. His reasons always seemed like poor excuses to Dalinar.

“It’s kind of bulky,” Dalinar noted.

“Well, it’s just an early model,” Navani said defensively. “I was working backward from one of those dreadful creations of Longshadow’s, and I didn’t have the luxury of refining the shape. I think it has a lot of potential. Imagine a few of these on a battlefield to dull the pain of wounded soldiers. Imagine it in the hands of a surgeon, who wouldn’t have to worry about his patients’ pain while working on them.”

Adolin nodded. Dalinar had to admit, it did sound like a useful device.

Navani smiled. “This is a special time to be alive; we’re learning all kinds of things about fabrials. This, for instance, is a diminishing fabrial— it decreases something, in this case pain. It doesn’t actually make the wound any better, but it might be a step in that direction. Either way, it’s a completely different type from paired fabrials like the spanreeds. If you could see the plans we have for the future…”

“Like what?” Adolin asked.

“You’ll find out eventually,” Navani said, smiling mysteriously. She removed the fabrial from Adolin’s hand.

“Shardblades?” Adolin sounded excited.

“Well, no,” Navani said. “The design and workings of Shardblades and Plate are completely different from everything we’ve discovered. The closest anyone has are those shields in Jah Keved. But as far as I can tell, they use a completely different design principle from regular Shardplate. The ancients must have had a wondrous grasp of engineering.”

“No,” Dalinar said. “I’ve seen them, Navani. They’re… well, they’re ancient. Their technology is primitive.”

“And the Dawncities?” Navani asked skeptically. “The fabrials?”

Dalinar shook his head. “I’ve seen neither. There are Shardblades in the visions, but they seem so out of place. Perhaps they were given directly by the Heralds, as the legends say.”

“Perhaps,” Navani said. “Why don’t—”

She vanished.

Dalinar blinked. He hadn’t heard the highstorm approaching.

He was now in a large, open room with pillars running along the sides. The enormous pillars looked sculpted of soft sandstone, with unornamented, granular sides. The ceiling was far above, carved from the rock in geometric patterns that looked faintly familiar. Circles connected by lines, spreading outward from one another…

“I don’t know what to do, old friend,” a voice said from the side. Dalinar turned to see a youthful man in regal white and gold robes, walking with his hands clasped before him, hidden by voluminous sleeves. He had dark hair pulled back in a braid and a short beard that came to a point. Gold threads were woven into his hair and came together on his forehead to form a golden symbol. The symbol of the Knights Radiant.

“They say that each time it is the same,” the man said. “We are never ready for the Desolations. We should be getting better at resisting, but each time we step closer to destruction instead.” He turned to Dalinar, as if expecting a response.

Dalinar glanced down. He too wore ornamental robes, though not as lavish. Where was he? What time? He needed to find clues for Navani to record and for Jasnah to use in proving—or disproving—these dreams.

“I don’t know what to say either,” Dalinar responded. If he wanted information, he needed to act more natural than he had in previous visions.

The regal man sighed. “I had hoped you would have wisdom to share with me, Karm.” They continued walking toward the side of the room, approaching a place where the wall split into a massive balcony with a stone railing. It looked out upon an evening sky; the setting sun stained the air a dirty, sultry red.

“Our own natures destroy us,” the regal man said, voice soft, though his face was angry. “Alakavish was a Surgebinder. He should have known better. And yet, the Nahel bond gave him no more wisdom than a regular man. Alas, not all spren are as discerning as honorspren.”

“I agree,” Dalinar said.

The other man looked relieved. “I worried that you would find my claims too forward. Your own Surgebinders were… But, no, we should not look backward.”

What’s a Surgebinder? Dalinar wanted to scream the question out, but there was no way. Not without sounding completely out of place.

Perhaps…

“What do you think should be done with these Surgebinders?” Dalinar asked carefully.

“I don’t know if we can force them to do anything.” Their footsteps echoed in the empty room. Were there no guards, no attendants? “Their power… well, Alakavish proves the allure that Surgebinders have for the common people. If only there were a way to encourage them….” The man stopped, turning to Dalinar. “They need to be better, old friend. We all do. The responsibility of what we’ve been given—whether it be the crown or the Nahel bond—needs to make us better.”

He seemed to expect something from Dalinar. But what?

“I can read your disagreement in your face,” the regal man said. “It’s all right, Karm. I realize that my thoughts on this subject are unconventional. Perhaps the rest of you are right, perhaps our abilities are proof of a divine election. But if this is true, should we not be more wary of how we act?”

Dalinar frowned. That sounded familiar to him. The regal man sighed, walking to the balcony lip. Dalinar joined him, stepping outside. The perspective finally allowed him to look down on the landscape below.

Thousands of corpses confronted him.

Dalinar gasped. Dead filled the streets of the city outside, a city that Dalinar vaguely recognized. Kholinar, he thought. My homeland. He stood with the regal man at the top of a low tower, three stories high—a keep of some sort, constructed of stone. It seemed to sit where the palace would someday be.

The city was unmistakable, with its peaked stone formations rising like enormous fins into the air. The windblades, they were called. But they were less weathered than he was accustomed to, and the city around them was very different. Built of blocky stone structures, many of which had been knocked down. The destruction spread far, lining the sides of primitive streets. Had the city been hit by an earthquake?

No, those corpses had fallen in battle. Dalinar could smell the stench of blood, viscera, smoke. The bodies lay strewn about, many near the low wall that surrounded the keep. The wall was broken in places, smashed. And there were rocks of strange shape mixed about the corpses. Stones cut like…

Blood of my fathers, Dalinar thought, gripping the stone railing, leading forward. Those aren’t stones. They’re creatures. Massive creatures, easily five or six times the size of a person, their skin dull and grey like granite. They had long limbs and skeletal bodies, the forelegs—or were they arms?—set into wide shoulders. The faces were lean, narrow. Arrowlike.

“What happened here?” Dalinar asked despite himself. “It’s terrible!”

“I ask myself this same thing. How could we let this occur? The Desolations are well named. I’ve heard initial counts. Eleven years of war, and nine out of ten people I once ruled are dead. Do we even have kingdoms to lead any longer? Sur is gone, I’m sure of it. Tarma, Eiliz, they won’t likely survive. Too many of their people have fallen.”

Dalinar had never heard of those places.

The man made a fist, pounding it softly against the railing. Burning stations had been set up in the distance; they had begun cremating the corpses. “The others want to blame Alakavish. And true, if he hadn’t brought us to war before the Desolation, we might not have been broken this badly. But Alakavish was a symptom of a greater disease. When the Heralds next return, what will they find? A people who have forgotten them yet again? A world torn by war and squabbling? If we continue as we have, then perhaps we deserve to lose.”

Dalinar felt a chill. He had thought that this vision must come after his previous one, but prior visions hadn’t been chronological. He hadn’t seen any Knights Radiant yet, but that might not be because they had disbanded. Perhaps they didn’t exist yet. And perhaps there was a reason this man’s words sounded so familiar.

Could it be? Could he really be standing beside the very man whose words Dalinar had listened to time and time again? “There is honor in loss,” Dalinar said carefully, using words repeated several times in The Way of Kings.

“If that loss brings learning.” The man smiled. “Using my own sayings against me again, Karm?”

Dalinar felt himself grow short of breath. The man himself. Nohadon. The great king. He was real. Or he had been real. This man was younger than Dalinar had imagined him, but that humble, yet regal bearing… yes, it was right.

“I’m thinking of giving up my throne,” Nohadon said softly.

“No!” Dalinar stepped toward him. “You mustn’t.”

“I cannot lead them,” the man said. “Not if this is what my leadership brings them to.”

“Nohadon.”

The man turned to him, frowning. “What?”

Dalinar paused. Could he be wrong about this man’s identity? But no. The name Nohadon was more of a title. Many famous people in history had been given holy names by the Church, before it was disbanded. Even Bajerden wasn’t likely to be his real name; that was lost in time.

“It is nothing,” Dalinar said. “You cannot give up your throne. The people need a leader.”

“They have leaders,” Nohadon said. “There are princes, kings, Soulcasters, Surgebinders. We never lack men and women who wish to lead.”

“True,” Dalinar said, “but we do lack ones who are good at it.”

Nohadon leaned over the railing. He stared at the fallen, an expression of deep grief—and trouble—on his face. It was so strange to see the man like this. He was so young. Dalinar had never imagined such insecurity, such torment, in him.

“I know that feeling,” Dalinar said softly. “The uncertainty, the shame, the confusion.”

“You can read me too well, old friend.”

“I know those emotions because I’ve felt them. I… I never assumed that you would feel them too.”

“Then I correct myself. Perhaps you don’t know me well enough.”

Dalinar fell silent.

“So what do I do?” Nohadon asked.

“You’re asking me?”

“You’re my advisor, aren’t you? Well, I should like some advice.”

“I… You can’t give up your throne.”

“And what should I do with it?” Nohadon turned and walked along the long balcony. It seemed to run around this entire level. Dalinar joined him, passing places where the stone was ripped, the railing broken away.

“I haven’t faith in people any longer, old friend,” Nohadon said. “Put two men together, and they will find something to argue about. Gather them into groups, and one group will find reason to oppress or attack another. Now this. How do I protect them? How do I stop this from happening again?”

“You dictate a book,” Dalinar said eagerly. “A grand book to give people hope, to explain your philosophy on leadership and how lives should be lived!”

“A book? Me. Write a book?”

“Why not?”

“Because it’s a fantastically stupid idea.”

Dalinar’s jaw dropped.

“The world as we know it has quite nearly been destroyed,” Nohadon said. “Barely a family exists that hasn’t lost half its members! Our best men are corpses on that field, and we haven’t food to last more than two or three months at best. And I’m to spend my time writing a book? Who would scribe it for me? All of my wordsmen were slaughtered when Yelignar broke into the chancery. You’re the only man of letters I know of who’s still alive.”

A man of letters? This was an odd time. “I could write it, then.”

“With one arm? Have you learned to write left-handed, then?”

Dalinar looked down. He had both of his arms, though apparently the man Nohadon saw was missing his right.

“No, we need to rebuild,” Nohadon said. “I just wish there were a way to convince the kings—the ones still alive—not to seek advantage over one another.” Nohadon tapped the balcony. “So this is my decision. Step down, or do what is needed. This isn’t a time for writing. It’s a time for action. And then, unfortunately, a time for the sword.”

The sword? Dalinar thought. From you, Nohadon?

It wouldn’t happen. This man would become a great philosopher; he would teach peace and reverence for others, and would not force men to do as he wished. He would guide them to acting with honor.

Nohadon turned to Dalinar. “I apologize, Karm. I should not dismiss your suggestions right after asking for them. I’m on edge, as I imagine that we all are. At times, it seems to me that to be human is to want that which we cannot have. For some, this is power. For me, it is peace.”

Nohadon turned, walking back down the balcony. Though his pace was slow, his posture indicated that he wished to be alone. Dalinar let him go.

“He goes on to become one of the most influential writers Roshar has ever known,” Dalinar said.

There was silence, save for the calls of the people working below, gathering the corpses.

“I know you’re there,” Dalinar said.

Silence.

“What does he decide?” Dalinar asked. “Did he unite them, as he wanted?”

The voice that often spoke in his visions did not come. Dalinar received no answer to his questions. He sighed, turning to look out over the fields of dead.

“You are right about one thing, at least, Nohadon. To be human is to want that which we cannot have.”

The landscape darkened, the sun setting. That darkness enveloped him, and he closed his eyes. When he opened them, he was back in his rooms, standing with his hands on the back of a chair. He turned to Adolin and Renarin, who stood nearby, anxious, prepared to grab him if he got violent.

“Well,” Dalinar said, “that was meaningless. I learned nothing. Blast! I’m doing a poor job of—”

“Dalinar,” Navani said curtly, still scribbling with a reed at her paper. “The last thing you said before the vision ended. What was it?”

Dalinar frowned. “The last…”

“Yes,” Navani said, urgent. “The very last words you spoke.”

“I was quoting the man I’d been speaking with. ‘To be human is to want that which we cannot have.’ Why?”

She ignored him, writing furiously. Once done, she slid off the high-legged chair, hurrying to his bookshelf. “Do you have a copy of… Yes, I thought you might. These are Jasnah’s books, aren’t they?”

“Yes,” Dalinar said. “She wanted them cared for until she returned.”

Navani pulled a volume off the shelf. “Corvana’s Analectics.” She set the volume on the writing desk and leafed through the pages.

Dalinar joined her, though—of course—he couldn’t make sense of the page. “What does it matter?”

“Here,” Navani said. She looked up at Dalinar. “When you go into these visions of yours, you know that you speak.”

“Gibberish. Yes, my sons have told me.”

“Anak malah kaf, del makian habin yah,” Navani said. “Sound familiar?”

Dalinar shook his head, baffled.

“It sounds a lot like what father was saying,” Renarin said. “When he was in the vision.”

“Not ‘a lot like’ Renarin,” Navani said, looking smug. “It’s exactly the same phrase. That is the last thing you said before coming out of your trance. I wrote down everything—as best I could—that you babbled today.”

“For what purpose?” Dalinar asked.

“Because,” Navani said “I thought it might be helpful. And it was. The same phrase is in the Analectics, almost exactly.”

“What?” Dalinar asked, incredulous. “How?”

“It’s a line from a song,” Navani said. “A chant by the Vanrial, an order of artists who live on the slopes of the Silent Mount in Jah Keved. Year after year, century after century, they’ve sung these same words—songs they claim were written in the Dawnchant by the Heralds themselves. They have the words of those songs, written in an ancient script. But the meanings have been lost. They’re just sounds, now. Some scholars believe that the script—and the songs themselves—may indeed be in the Dawnchant.”

“And I…” Dalinar said.

“You just spoke a line from one of them,” Navani said. “Beyond that, if the phrase you just gave me is correct, you translated it. This could prove the Vanrial Hypothesis! One sentence isn’t much, but it could give us the key to translating the entire script. It has been itching at me for a while, listening to these visions. I thought the things you were saying had too much order to be gibberish.” She looked at Dalinar, smiling deeply. “Dalinar, you might just have cracked one of the most perplexing—and ancient— mysteries of all time.”

“Wait,” Adolin said. “What are you saying?”

“What I’m saying, nephew,” Navani said, looking directly at him, “is that we have your proof.”

“But,” Adolin said. “I mean, he could have heard that one phrase…”

“And extrapolated an entire language from it?” Navani said, holding up a sheet full of writings. “This is not gibberish, but it’s no language that people now speak. I suspect it is what it seems, the Dawnchant. So unless you can think of another way your father learned to speak a dead language, Adolin, the visions are most certainly real.”

The room fell silent. Navani herself looked stunned by what she had said. She shook it off quickly. “Now, Dalinar,” she said, “I want you to describe this vision as accurately as possible. I need the exact words you spoke, if you can recall them. Every bit we gather will help my scholars sort through this….”