You do not agree with my quest. I understand that, so much as it is possible to understand someone with whom I disagree so completely.

Four hours after the chasmfiend attack, Adolin was still overseeing the cleanup. In the struggle, the monster had destroyed the bridge leading back to the warcamps. Fortunately, some soldiers had been left on the other side, and they’d gone to fetch a bridge crew.

Adolin walked amid the soldiers, gathering reports as the late afternoon sun inched toward the horizon. The air had a musty, moldy scent. The smell of greatshell blood. The beast itself lay where it had fallen, chest cut open. Some soldiers were harvesting its carapace amid cremlings that had come out to feast on the carcass. To Adolin’s left, long lines of men lay in rows, using cloaks or shirts as pillows on the ragged plateau surface. Surgeons from Dalinar’s army tended them. Adolin blessed his father for always bringing the surgeons, even on a routine expedition like this one.

He continued on his way, still wearing his Shardplate. The troops could have made their way back to the warcamps by another route—there was still a bridge on the other side, leading farther out onto the Plains. They could have moved eastward, then wrapped back around. Dalinar, however, had made the call—much to Sadeas’s dismay—that they would wait and tend the wounded, resting the few hours it would take to get a bridge crew.

Adolin glanced toward the pavilion, which tinkled with laughter. Several large rubies glowed brightly, set atop poles, with worked golden tines holding them in place. They were fabrials that gave off heat, though there was no fire involved. He didn’t understand how fabrials worked, though the more spectacular ones needed large gemstones to function.

Once again, the other lighteyes enjoyed their leisure while he worked. This time he didn’t mind. He would have found it difficult to enjoy himself after such a disaster. And it had been a disaster. A minor lighteyed officer approached, carrying a final list of casualties. The man’s wife read it, then they left him with the sheet and retreated.

There were nearly fifty men dead, twice as many wounded. Many were men Adolin had known. When the king had been given the initial estimate, he had brushed aside the deaths, indicating that they’d be rewarded for their valor with positions in the Heraldic Forces above. He seemed to have conveniently forgotten that he’d have been one of the casualties himself, if not for Dalinar.

Adolin sought out his father with his eyes; Dalinar stood at the edge of the plateau, looking eastward again. What did he search for out there? This wasn’t the first time Adolin had seen such extraordinary actions from his father, but they had seemed particularly dramatic. Standing beneath the massive chasmfiend, holding it back from killing his nephew, Plate glowing. That image was fixed in Adolin’s memory.

The other lighteyes stepped more lightly around Dalinar now, and during the last few hours, Adolin hadn’t heard a single mention of his weakness, not even from Sadeas’s men. He feared it wouldn’t last. Dalinar was heroic, but only infrequently. In the weeks that followed, the others would begin to talk again of how he rarely went on plateau assaults, about how he’d lost his edge.

Adolin found himself thirsting for more. Today when Dalinar had leaped to protect Elhokar, he’d acted like the stories said he had during his youth. Adolin wanted that man back. The kingdom needed him.

Adolin sighed, turning away. He needed to give the final casualty report to the king. Likely he’d be mocked for it, but perhaps—in waiting to deliver it—he might be able to listen in on Sadeas. Adolin still felt he was missing something about that man. Something his father saw, but he did not.

So, steeling himself for the barbs, he made his way toward the pavilion.

Dalinar faced eastward with gauntleted hands clasped behind his back. Somewhere out there, at the center of the Plains, the Parshendi made their base camp.

Alethkar had been at war for nearly six years, engaging in an extended siege. The siege strategy had been suggested by Dalinar himself—striking at the Parshendi base would have required camping on the Plains, weathering highstorms, and relying on a large number of fragile bridges. One failed battle, and the Alethi could have found themselves trapped and surrounded, without any way back to fortified positions.

But the Shattered Plains could also be a trap for the Parshendi. The eastern and southern edges were impassable—the plateaus there were weathered to the point that many were little more than spires, and the Parshendi could not jump the distance between them. The Plains were edged by mountains, and packs of chasmfiends prowled the land between, enormous and dangerous.

With the Alethi army boxing them in on the west and north—and with scouts placed south and east just in case—the Parshendi could not escape. Dalinar had argued that the Parshendi would run out of supplies. They’d either have to expose themselves and try to escape the Plains, or would have to attack the Alethi in their fortified warcamps.

It had been an excellent plan. Except, Dalinar hadn’t anticipated the gemhearts.

He turned from the chasm, walking across the plateau. He itched to go see to his men, but he needed to show trust in Adolin. He was in command, and he would do well by it. In fact, it seemed he was already taking some final reports over to Elhokar.

Dalinar smiled, looking at his son. Adolin was shorter than Dalinar, and his hair was blond mixed with black. The blond was an inheritance from his mother, or so Dalinar had been told. Dalinar himself remembered nothing of the woman. She had been excised from his memory, leaving strange gaps and foggy areas. Sometimes he could remember an exact scene, with everyone else crisp and clear, but she was a blur. He couldn’t even remember her name. When others spoke it, it slipped from his mind, like a pat of butter sliding off a too-hot knife.

He left Adolin to make his report and walked up to the chasmfiend’s carcass. It lay slumped over on its side, eyes burned out, mouth lying open. There was no tongue, just the curious teeth of a greatshell, with a strange, complex network of jaws. Some flat platelike teeth for crushing and destroying shells and other, smaller mandibles for ripping off flesh or shoving it deeper into the throat. Rockbuds had opened nearby, their vines reaching out to lap up the beast’s blood. There was a connection between a man and the beast he hunted, and Dalinar always felt a strange melancholy after killing a creature as majestic as a chasmfiend.

Most gemhearts were harvested quite differently than the one had been today. Sometime during the strange life cycle of the chasmfiends, they sought the western side of the Plains, where the plateaus were wider. They climbed up onto the tops and made a rocky chrysalis, waiting for the coming of a highstorm.

During that time, they were vulnerable. You just had to get to the plateau where it rested, break into its chrysalis with some mallets or a Shardblade, then cut out the gemheart. Easy work for a fortune. And the beasts came frequently, often several times a week, so long as the weather didn’t get too cold.

Dalinar looked up at the hulking carcass. Tiny, near-invisible spren were floating out of the beast’s body, vanishing into the air. They looked like the tongues of smoke that might come off a candle after being snuff ed. Nobody knew what kind of spren they were; you only saw them around the freshly killed bodies of greatshells.

He shook his head. The gemhearts had changed everything for the war. The Parshendi wanted them too, wanted them badly enough to extend themselves. Fighting the Parshendi for the greatshells made sense, for the Parshendi could not replenish their troops from home as the Alethi could. So contests over the greatshells were both profitable and a tactically sound way of advancing the siege.

With the evening coming on, Dalinar could see lights twinkling across the Plains. Towers where men watched for chasmfiends coming up to pupate. They’d watch through the night, though chasmfiends rarely came in the evening or night. The scouts crossed chasms with jumping poles, moving very lightly from plateau to plateau without the need of bridges. Once a chasmfiend was spotted the scouts would sound warning, and it became a race—Alethi against Parshendi. Seize the plateau and hold it long enough to get out the gemheart, attack the enemy if they got there first.

Each highprince wanted those gemhearts. Paying and feeding thousands of troops was not cheap, but a single gemheart could cover a highprince’s expenses for months. Beyond that, the larger a gemstone was when used by a Soulcaster, the less likely it was to shatter. Enormous gemheart stones offered near-limitless potential. And so, the highprinces raced. The first one to a chrysalis got to fight the Parshendi for the gemheart.

They could have taken turns, but that was not the Alethi way. Competition was doctrine to them. Vorinism taught that the finest warriors would have the holy privilege of joining the Heralds after death, fighting to reclaim the Tranquiline Halls from the Voidbringers. The highprinces were allies, but they were also rivals. To give up a gemheart to another…well, it felt wrong. Better to have a contest. And so what had been a war had become sport instead. Deadly sport—but that was the best kind.

Dalinar left the fallen chasmfiend behind. He understood each step in the process of what had happened during these six years. He’d even hastened some of them. Only now did he worry. They were making headway in cutting down the Parshendi numbers, but the original goal of vengeance for Gavilar’s murder had nearly been forgotten. The Alethi lounged, they played, and they idled.

Even though they’d killed plenty of Parshendi—as many as a quarter of their originally estimated forces were dead—this was just taking so long. The siege had lasted six years, and could easily take another six. That troubled him. Obviously the Parshendi had expected to be besieged here. They’d prepared supply dumps and had been ready to move their entire population to the Shattered Plains, where they could use these Heralds-forsaken chasms and plateaus like hundreds of moats and fortifications.

Elhokar had sent messengers, demanding to know why the Parshendi had killed his father. They had never given an answer. They’d taken credit for his murder, but had offered no explanation. Of late, it seemed that Dalinar was the only one who still wondered about that.

Dalinar turned to the side; Elhokar’s attendants had retired to the pavilion, enjoying wine and refreshments. The large open-sided tent was dyed violet and yellow, and a light breeze ruffled the canvas. There was a small chance that another highstorm might arrive tonight, the stormwardens said. Almighty send that the army was back to the camp if one did come.

Highstorms. Visions.

Unite them….

Did he really believe in what he’d seen? Did he really think that the Almighty himself had spoken to him? Dalinar Kholin, the Blackthorn, a fearsome warlord?

Unite them.

At the pavilion, Sadeas walked out into the night. He had removed his helm, revealing a head of thick black hair that curled and tumbled around his shoulders. He cut an imposing figure in his Plate; he certainly looked much better in armor than he did wearing one of those ridiculous costumes of lace and silk that were popular these days.

Sadeas caught Dalinar’s eyes, nodding slightly. My part is done, that nod said. Sadeas strolled for a moment, then reentered the pavilion.

So. Sadeas had remembered the reason for inviting Vamah on the hunt. Dalinar would have to seek out Vamah. He made his way toward the pavilion. Adolin and Renarin lurked near the king. Had the lad given his report yet? It seemed likely that Adolin was trying—yet again—to listen in on Sadeas’s conversations with the king. Dalinar would have to do something about that; the boy’s personal rivalry with Sadeas was understandable, perhaps, but counterproductive.

Sadeas was chatting with the king. Dalinar made to go find Vamah—the other highprince was near the back of the pavilion—but the king interrupted him.

“Dalinar,” the king said. “Come here. Sadeas tells me he has won three gemhearts in the last few weeks alone!”

“He has indeed,” Dalinar said, approaching.

“How many have you won?”

“Including the one today?”

“No,” the king said. “Before this.”

“None, Your Majesty,” Dalinar admitted.

“It’s Sadeas’s bridges,” Elhokar said. “They’re more efficient than yours.”

“I may not have won anything the last few weeks,” Dalinar said stiffly, “but my army has won its share of skirmishes in the past.” And the gemhearts can go to Damnation, for all I care.

“Perhaps,” Elhokar said, “but what have you done lately?”

“I have been busy with other important things.”

Sadeas raised an eyebrow. “More important than the war? More important than vengeance? Is that possible? Or are you just making excuses?”

Dalinar gave the other highprince a pointed look. Sadeas just shrugged. They were allies, but they were not friends. Not any longer.

“You should switch to bridges like his,” Elhokar said.

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “Sadeas’s bridges waste many lives.”

“But they are also fast,” Sadeas said smoothly. “Relying on wheeled bridges is foolish, Dalinar. Getting them over this plateau terrain is slow and plodding.”

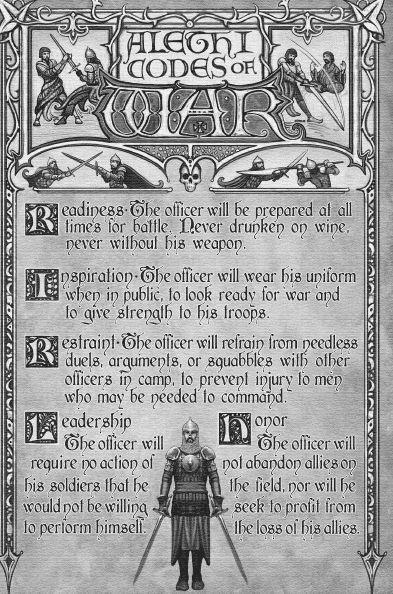

“The Codes state that a general may not ask a man to do anything he would not do himself. Tell me, Sadeas. Would you run at the front of those bridges you use?”

“I wouldn’t eat gruel either,” Sadeas said dryly, “or cut ditches.”

“But you might if you had to,” Dalinar said. “The bridges are different. Stormfather, you don’t even let them use armor or shields! Would you enter combat without your Plate?”

“The bridgemen serve a very important function,” Sadeas snapped. “They distract the Parshendi from firing at my soldiers. I tried giving them shields at first. And you know what? The Parshendi ignored the bridgemen and fired volleys onto my soldiers and horses. I found that by doubling the number of bridges on a run, then making them extremely light—no armor, no shields to slow them—the bridgemen work far better.

“You see, Dalinar? The Parshendi are too tempted by the exposed bridgemen to fire at anyone else! Yes, we lose a few bridge crews in each assault, but rarely so many that it hinders us. The Parshendi just keep firing at them—I assume that, for whatever reason, they think killing the bridgemen hurts us. As if an unarmored man carrying a bridge was worth the same to the army as a mounted knight in Plate.” Sadeas shook his head in amusement at the thought.

Dalinar frowned. Brother, Gavilar had written. You must find the most important words a man can say…. A quote from the ancient text The Way of Kings. It would disagree strongly with the things Sadeas was implying.

“Regardless,” Sadeas continued. “Surely you can’t argue with how effective my method has been.”

“Sometimes,” Dalinar said, “the prize is not worth the costs. The means by which we achieve victory are as important as the victory itself.”

Sadeas looked at Dalinar incredulously. Even Adolin and Renarin—who had come closer—seemed shocked by the statement. It was a very un-Alethi way of thinking.

With the visions and the words of that book spinning in his mind lately, Dalinar wasn’t feeling particularly Alethi.

“The prize is worth any cost, Brightlord Dalinar,” Sadeas said. “Winning the competition is worth any effort, any expense.”

“It is a war,” Dalinar said. “Not a contest.”

“Everything is a contest,” Sadeas said with a wave of his hand. “All dealings among men are a contest in which some will succeed and others fail. And some are failing quite spectacularly.”

“My father is one of the most renowned warriors in Alethkar!” Adolin snapped, butting into the group. The king raised an eyebrow at him, but otherwise stayed out of the conversation. “You saw what he did earlier, Sadeas, while you were hiding back by the pavilion with your bow. My father held off the beast. You’re a cowa—”

“Adolin!” Dalinar said. That was going too far. “Restrain yourself.”

Adolin clenched his jaw, hand to his side, as if itching to summon his Shardblade. Renarin stepped forward and gently placed a hand on Adolin’s arm. Reluctantly, Adolin backed down.

Sadeas turned to Dalinar, smirking. “One son can barely control himself, and the other is incompetent. This is your legacy, old friend?”

“I am proud of them both, Sadeas, whatever you think.”

“The firebrand I can understand,” Sadeas said. “You were once impetuous just like him. But the other one? You saw how he ran out onto the field today. He even forgot to draw his sword or bow! He’s useless!”

Renarin flushed, looking down. Adolin snapped his head up. He thrust his hand to the side again, stepping forward toward Sadeas.

“Adolin!” Dalinar said. “I will handle this!”

Adolin looked at him, blue eyes alight with rage, but he did not summon his Blade.

Dalinar turned his attention to Sadeas, speaking very softly, very pointedly. “Sadeas. Surely I did not just hear you openly—before the king—call my son useless. Surely you would not say that, as such an insult would demand that I summon my Blade and seek your blood. Shatter the Vengeance Pact. Cause the king’s two greatest allies to kill one another. Surely you would not have been that foolish. Surely I misheard.”

Everything grew still. Sadeas hesitated. He didn’t back down; he met Dalinar’s gaze. But he did hesitate.

“Perhaps,” Sadeas said slowly, “you did hear the wrong words. I would not insult your son. That would not have been…wise of me.”

An understanding passed between them, stares locked, and Dalinar nodded. Sadeas did as well—one curt nod of the head. They would not let their hatred of one another become a danger to the king. Barbs were one thing, but dueling offenses were another. They couldn’t risk that.

“Well,” Elhokar said. He allowed his highprinces to jostle and contend for status and influence. He believed they were all stronger for it, and few faulted him; it was an established method of rule. More and more, Dalinar found himself disagreeing.

Unite them….

“I guess we can be done with that,” Elhokar said.

To the side, Adolin looked unsatisfied, as if he’d really been hoping that Dalinar would summon his Blade and confront Sadeas. Dalinar’s own blood felt hot, the Thrill tempting him, but he shoved it down. No. Not here. Not now. Not while Elhokar needed them.

“Perhaps we can be done, Your Majesty,” Sadeas said. “Though I doubt this particular discussion between Dalinar and me will ever be done. At least until he relearns how to act as a man should.”

“I said that is quite enough, Sadeas,” Elhokar said.

“Quite enough, you say?” a new voice added. “I believe that a single word from Sadeas is ‘quite enough’ for anyone.” Wit picked his way through the groups of attendants, holding a cup of wine in one hand, silver sword belted at his side.

“Wit!” Elhokar exclaimed. “When did you get here?”

“I caught up to your party just before the battle, Your Majesty,” Wit said, bowing. “I was going to speak with you, but the chasmfiend beat me to you. I hear your conversation with it was rather energizing.”

“But, you arrived hours ago, then! What have you been doing? How could I have missed seeing you here?”

“I had…things to be about,” Wit said. “But I couldn’t stay away from the hunt. I wouldn’t want you to lack for me.”

“I’ve done well so far.”

“And yet, you were still Witless,” Wit noted.

Dalinar studied the black-clad man. What to make of Wit? He was clever. And yet, he was too free with his thoughts, as he’d shown with Renarin earlier. This Wit had a strange air about him that Dalinar couldn’t quite place.

“Brightlord Sadeas,” Wit said, taking a sip of wine. “I’m terribly sorry to see you here.”

“I should think,” Sadeas said dryly, “that you would be happy to see me. I seem always to provide you with such entertainment.”

“That is unfortunately true,” Wit said.

“Unfortunately?”

“Yes. You see, Sadeas, you make it too easy. An uneducated, half-brained serving boy with a hangover could make mock of you. I am left with no need to exert myself, and your very nature makes mockery of my mockery. And so it is that through sheer stupidity you make me look incompetent.”

“Really, Elhokar,” Sadeas said. “Must we put up with this…creature?”

“I like him,” Elhokar said, smiling. “He makes me laugh.”

“At the expense of those who are loyal to you.”

“Expense?” Wit cut in. “Sadeas, I don’t believe you’ve ever paid me a sphere. Though no, please, don’t offer. I can’t take your money, as I know how many others you must pay to get what you wish of them.”

Sadeas flushed, but kept his temper. “A whore joke, Wit? Is that the best you can manage?”

Wit shrugged. “I point out truths when I see them, Brightlord Sadeas. Each man has his place. Mine is to make insults. Yours is to be in-sluts.”

Sadeas froze, then grew red-faced. “You are a fool.”

“If the Wit is a fool, then it is a sorry state for men. I shall offer you this, Sadeas. If you can speak, yet say nothing ridiculous, I will leave you alone for the rest of the week.”

“Well, I think that shouldn’t be too difficult.”

“And yet you failed,” Wit said, sighing. “For you said ‘I think’ and I can imagine nothing so ridiculous as the concept of you thinking. What of you, young Prince Renarin? Your father wishes me to leave you alone. Can you speak, yet say nothing ridiculous?”

Eyes turned toward Renarin, who stood just behind his brother. Renarin hesitated, eyes opening wide at the attention. Dalinar grew tense.

“Nothing ridiculous,” Renarin said slowly.

Wit laughed. “Yes, I suppose that will satisfy me. Very clever. If Brightlord Sadeas should lose control of himself and finally kill me, perhaps you can be King’s Wit in my stead. You seem to have the mind for it.”

Renarin perked up, which darkened Sadeas’s mood further. Dalinar eyed the highprince; Sadeas’s hand had gone to his sword. Not a Shardblade, for Sadeas didn’t have one. But he did carry a lighteyes’s side sword. Plenty deadly; Dalinar had fought beside Sadeas on many occasions, and the man was an expert swordsman.

Wit stepped forward. “So what of it, Sadeas?” he asked softly. “You going to do Alethkar a favor and rid it of us both?”

Killing the King’s Wit was legal. But by so doing, Sadeas would forfeit his title and lands. Most men found it a poor enough trade not to do it in the open. Of course, if you could assassinate a Wit without anyone knowing it was you, that was something different.

Sadeas slowly removed his hand from the hilt of his sword, then nodded curtly to the king and strode away.

“Wit,” Elhokar said, “Sadeas has my favor. There’s no need to torment him so.”

“I disagree,” Wit said. “The king’s favor may be torment enough for most men, but not him.”

The king sighed and looked toward Dalinar. “I should go placate Sadeas. I’ve been meaning to ask you, though. Have you looked into the issue I asked you about earlier?”

Dalinar shook his head. “I have been busy with the needs of the army. But I will look into it now, Your Majesty.”

The king nodded, then hastened off after Sadeas.

“What was that, Father?” Adolin asked. “Is it about the people he thinks were spying on him?”

“No,” Dalinar said. “This is something new. I’ll show you shortly.”

Dalinar looked toward Wit. The black-clad man was popping his knuckles one at a time, looking at Sadeas, seeming contemplative. He noticed Dalinar watching and winked, then walked away.

“I like him,” Adolin repeated.

“I might be persuaded to agree,” Dalinar said, rubbing his chin. “Renarin,” Dalinar said, “go and get a report on the wounded. Adolin, come with me. We need to check into the matter the king spoke of.”

Both young men looked confused, but they did as requested. Dalinar started across the plateau toward where the carcass of the chasmfiend lay.

Let us see what your worries have brought us this time, nephew, he thought.

Adolin turned the long leather strap over in his hands. Almost a handspan wide and a finger’s width thick, the strap ended in a ragged tear. It was the girth to the king’s saddle, the strap that wrapped under the horse’s barrel. It had broken suddenly during the fight, throwing the saddle—and the king—from horseback.

“What do you think?” Dalinar asked.

“I don’t know,” Adolin said. “It doesn’t look that worn, but I guess it was, otherwise it wouldn’t have snapped, right?

Dalinar took the strap back, looking contemplative. The soldiers still hadn’t returned with the bridge crew, though the sky was darkening.

“Father,” Adolin said. “Why would Elhokar ask us to look into this? Does he expect us to discipline the grooms for not properly caring for his saddle? Is it…” Adolin trailed off, and he suddenly understood his father’s hesitation. “The king thinks the strap was cut, doesn’t he?”

Dalinar nodded. He turned it over in his gauntleted fingers, and Adolin could see him thinking about it. A girth could get so worn that it would snap, particularly when strained by the weight of a man in Shardplate. This strap had broken off at the point where it had been affixed to the saddle, so it would have been easy for the grooms to miss it. That was the most rational explanation. But when looked at with slightly more irrational eyes, it could seem that something nefarious had happened.

“Father,” Adolin said, “he’s getting increasingly paranoid. You know he is.”

Dalinar didn’t reply.

“He sees assassins in every shadow,” Adolin continued. “Straps break. That doesn’t mean someone tried to kill him.”

“If the king is worried,” Dalinar said, “we should look into it. The break is smoother on one side, as if it were sliced so that it would rip when it was stressed.”

Adolin frowned. “Maybe.” He hadn’t noticed that. “But think about it, Father. Why would someone cut his strap? A fall from horseback wouldn’t harm a Shardbearer. If it was an assassination attempt, then it was an incompetent one.”

“If it was an assassination attempt,” Dalinar said, “even an incompetent one, then we have something to worry about. It happened on our watch, and his horse was cared for by our grooms. We will look into this.”

Adolin groaned, some of his frustration slipping out. “The others already whisper that we’ve become bodyguards and pets of the king. What will they say if they hear that we’re chasing down his every paranoid worry, no matter how irrational?”

“I have never cared what they say.”

“We spend all our time on bureaucracy while others win wealth and glory. We rarely go on plateau assaults because we’re busy doing things like this! We need to be out there, fighting, if we’re ever going to catch up to Sadeas!”

Dalinar looked at him, frown deepening, and Adolin bit off his next outburst.

“I see that we’re no longer talking about this broken girth,” Dalinar said.

“I…I’m sorry. I spoke in haste.”

“Perhaps you did. But then again, perhaps I needed to hear it. I noticed that you didn’t particularly like how I held you back from Sadeas earlier.”

“I know you hate him too, Father.”

“You do not know as much as you presume you do,” Dalinar said. “We’ll do something about that in a moment. For now, I swear…this strap does look like it was cut. Perhaps there is something we’re not seeing. This could have been part of something larger that didn’t work the way it had been anticipated.”

Adolin hesitated. It seemed overcomplicated, but if there was a group who liked their plots overly complicated, it was the Alethi lighteyes. “Do you think one of the highprinces may have tried something?”

“Maybe,” Dalinar said. “But I doubt any of them want him dead. So long as Elhokar rules, the highprinces get to fight in this war their way and fatten their purses. He doesn’t make many demands of them. They like having him as their king.”

“Men can covet the throne for the distinction alone.”

“True. When we return, see if anyone has been bragging too much of late. Check to see if Roion is still bitter about Wit’s insult at the feast last week and have Talata go over the contracts Highprince Bethab offered to the king for the use of his chulls. In previous contracts, he’s tried to slip in language that would favor his claim in a succession. He’s been bold ever since your aunt Navani left.”

Adolin nodded.

“See if you can backtrack the girth’s history,” Dalinar said. “Have a leatherworker look at it and tell you what he thinks of the rip. Ask the grooms if they noticed anything, and watch to see if any have received any suspicious windfalls of spheres lately.” He hesitated. “And double the king’s guard.”

Adolin turned, glancing at the pavilion. Sadeas was strolling out of it. Adolin narrowed his eyes. “Do you think—”

“No,” Dalinar interrupted.

“Sadeas is an eel.”

“Son, you have to stop fixating on him. He likes Elhokar, which can’t be said of most of the others. He’s one of the few I’d trust the king’s safety to.”

“I wouldn’t do the same, Father, I can tell you that.”

Dalinar fell silent for a moment. “Come with me.” He handed Adolin the saddle strap, then began to cross the plateau toward the pavilion. “I want to show you something about Sadeas.”

Resigned, Adolin followed. They passed the lit pavilion. Inside, darkeyed men served food and drink while women sat and scribed messages or wrote accounts of the battle. The lighteyes spoke with one another in verbose, excited tones, complimenting the king’s bravery. The men wore dark, masculine colors: maroon, navy, forest green, deep burnt orange.

Dalinar approached Highprince Vamah, who stood outside the pavilion with a group of his own lighteyed attendants. He was dressed in a fashionable long brown coat that had slashes cut through it to expose the bright yellow silk lining. It was a subdued fashion, not as ostentatious as wearing silks on the outside. Adolin thought it looked nice.

Vamah himself was a round-faced, balding man. The short hair that remained stuck straight up, and he had light grey eyes. He had a habit of squinting—which he did as Dalinar and Adolin approached.

What is this about? Adolin wondered.

“Brightlord,” Dalinar said to Vamah. “I have come to make certain your comfort has been seen to.”

“My comfort would be best seen to if we could be on our way back.” Vamah glared over at the setting sun, as if blaming it for some misdeed. He wasn’t normally so foul-mooded.

“I’m certain that my men are moving as quickly as they can,” Dalinar said.

“It wouldn’t be nearly as late if you hadn’t slowed us so much on the way here,” Vamah said.

“I like to be careful,” Dalinar said. “And, speaking of care, there is something I’ve been meaning to talk to you about. Might my son and I speak to you alone for a moment?”

Vamah scowled, but let Dalinar lead him away from his attendants. Adolin followed, more and more baffled.

“The beast was a large one,” Dalinar said to Vamah, nodding toward the fallen chasmfiend. “The biggest I’ve seen.”

“I suppose.”

“I hear you’ve had success on your recent plateau assaults, killing a few cocooned chasmfiends of your own. You are to be congratulated.”

Vamah shrugged. “The ones we won were small. Nothing like that gemheart that Elhokar took today.”

“A small gemheart is better than none,” Dalinar said politely. “I hear that you have plans to augment the walls of your warcamp.”

“Hum? Yes. Fill in a few of the gaps, improve the fortification.”

“I’ll be certain to tell His Majesty that you’ll be wanting to purchase extra access to the Soulcasters.”

Vamah turned to him, frowning. “Soulcasters?”

“For lumber,” Dalinar said evenly. “Surely you don’t intend to fill in the walls without using scaffolding? Out here, on these remote plains, it’s fortunate that we have Soulcasters to provide things like wood, wouldn’t you say?”

“Er, yes,” Vamah said, expression darkening further. Adolin looked from him to his father. There was a subtext to the conversation. Dalinar wasn’t speaking only of wood for the walls—the Soulcasters were the means by which all of the highprinces fed their armies.

“The king is quite generous in allowing access to the Soulcasters,” Dalinar said. “Wouldn’t you agree, Vamah?”

“I take your point, Dalinar,” Vamah said dryly. “No need to keep bashing the rock into my face.”

“I’ve never been known as a subtle man, Brightlord,” Dalinar said. “Just an effective one.” He walked away, waving for Adolin to follow. Adolin did so, looking over his shoulder at the other highprince.

“He’s been complaining vocally about the fees that Elhokar charges to use his Soulcasters,” Dalinar said softly. It was the primary form of taxation the king levied on the highprinces. Elhokar himself didn’t fight for, or win, gemhearts except on the occasional hunt. He stood aloof from fighting personally in the war, as was appropriate.

“And so…?” Adolin said.

“So I reminded Vamah of how much he relies on the king.”

“I suppose that’s important. But what does it have to do with Sadeas?”

Dalinar didn’t answer. He kept walking across the plateau, stepping up to the lip of the chasm. Adolin joined him, waiting. A few seconds later, someone approached from behind in clinking Shardplate, then Sadeas stepped up beside Dalinar at the lip of the chasm. Adolin narrowed his eyes at the man, and Sadeas raised an eyebrow, but said nothing about his presence.

“Dalinar,” Sadeas said, turning his eyes forward, looking out across the Plains.

“Sadeas.” Dalinar’s voice was controlled and curt.

“You spoke with Vamah?”

“Yes. He saw through what I was doing.”

“Of course he did.” There was a hint of amusement in Sadeas’s voice. “I wouldn’t have expected anything else.”

“You told him you were increasing what you charge him for wood?”

Sadeas controlled the only large forest in the region. “Doubling it,” Sadeas said.

Adolin looked over his shoulder. Vamah was watching them stand there, and his expression was as thunderous as a highstorm, angerspren boiling up from the ground around him like small pools of bubbling blood. Dalinar and Sadeas together sent him a very sound message. Why…this is probably why they invited him on the hunt, Adolin realized. So they could maneuver him.

“Will it work?” Dalinar asked.

“I’m certain it will,” Sadeas said. “Vamah’s an agreeable enough fellow, when prodded—he’ll see that it’s better to use the Soulcasters than spend a fortune running a supply line back to Alethkar.”

“Perhaps we should tell the king about these sorts of things,” Dalinar said, glancing at the king, who stood in the pavilion, oblivious of what had been done.

Sadeas sighed. “I’ve tried; he hasn’t a mind for this sort of work. Leave the boy to his preoccupations, Dalinar. His are the grand ideals of justice, holding the sword high as he rides against his father’s enemies.”

“Lately, he seems less preoccupied with the Parshendi, and more worried about assassins in the night,” Dalinar said. “The boy’s paranoia worries me. I don’t know where he gets it.”

Sadeas laughed. “Dalinar, are you serious?”

“I’m always serious.”

“I know, I know. But surely you can see where the boy comes by the paranoia!”

“From the way his father was killed?”

“From the way his uncle treats him! A thousand guards? Halts on each and every plateau to let soldiers ‘secure’ the next one over? Really, Dalinar?”

“I like to be careful.”

“Others call that being paranoid.”

“The Codes—”

“The Codes are a bunch of idealized nonsense,” Sadeas said, “devised by poets to describe the way they think things should have been.”

“Gavilar believed in them.”

“And look where it got him.”

“And where were you, Sadeas, when he was fighting for his life?”

Sadeas’s eyes narrowed. “So we’re going to rehash that now? Like old lovers, crossing paths unexpectedly at a feast?”

Adolin’s father didn’t reply. Once again, Adolin found himself baffled by Dalinar’s relationship with Sadeas. Their barbs were genuine; one needed only look in their eyes to see that the men could barely stand one another.

And yet, here they were, apparently planning and executing a joint manipulation of another highprince.

“I’ll protect the boy my way,” Sadeas said. “You do it your way. But don’t complain to me about his paranoia when you insist on wearing your uniform to bed, just in case the Parshendi suddenly decide—against all reason and precedent—to attack the warcamps. ‘I don’t know where he gets it’ indeed!”

“Let’s go, Adolin,” Dalinar said, turning to stride away. Adolin followed.

“Dalinar,” Sadeas called from behind.

Dalinar hesitated, looking back.

“Have you found it yet?” Sadeas asked. “Why he wrote what he did?”

Dalinar shook his head.

“You’re not going to find the answer,” Sadeas said. “It’s a foolish quest, old friend. One that’s tearing you apart. I know what happens to you during storms. Your mind is unraveling because of all this stress you put upon yourself.”

Dalinar returned to walking away. Adolin hurried after him. What had that last part been about? Why “he” wrote? Men didn’t write. Adolin opened his mouth to ask, but he could sense his father’s mood. This was not a time to prod him.

He walked with Dalinar up to a small rock hill on the plateau. They picked their way up it to the top, and from there looked out at the fallen chasmfiend. Dalinar’s men continued harvesting its meat and carapace.

He and his father stood there for a time, Adolin brimming with questions, yet unable to find a way to phrase them.

Eventually, Dalinar spoke. “Have I ever told you what Gavilar’s final words to me were?”

“You haven’t. I’ve always wondered about that night.”

“‘Brother, follow the Codes tonight. There is something strange upon the winds.’ That’s what he said to me, the last thing he told me just before we began the treaty-signing celebration.”

“I didn’t realize that Uncle Gavilar followed the Codes.”

“He’s the one who first showed them to me. He found them as a relic of old Alethkar, back when we’d first been united. He began following them shortly before he died.” Dalinar grew hesitant. “Those were odd days, son. Jasnah and I weren’t sure what to think of the changes in Gavilar. At the time, I thought the Codes foolishness, even the one that commanded an officer to avoid strong drink during times of war. Especially that one.” His voice grew even softer. “I was unconscious on the ground when Gavilar was murdered. I can remember voices, trying to wake me up, but I was too addled by my wine. I should have been there for him.”

He looked to Adolin. “I cannot live in the past. It is foolishness to do so. I blame myself for Gavilar’s death, but there is nothing to be done for him now.”

Adolin nodded.

“Son, I keep hoping that if I make you follow the Codes long enough, you will see—as I have—their importance. Hopefully you will not need as dramatic an example of it as I did. Regardless, you need to understand. You speak of Sadeas, of beating him, of competing with him. Do you know of Sadeas’s part in my brother’s death?”

“He was the decoy,” Adolin said. Sadeas, Gavilar, and Dalinar had been good friends up until the king’s death. Everyone knew it. They had conquered Alethkar together.

“Yes,” Dalinar said. “He was with the king and heard the soldiers crying that a Shardbearer was attacking. The decoy idea was Sadeas’s plan—he put on one of Gavilar’s robes and fled in Gavilar’s place. It was suicide, what he did. Wearing no Plate, making a Shardbearer assassin chase him. I honestly think it was one of the bravest things I’ve ever known a man to do.”

“But it failed.”

“Yes. And there’s a part of me that can never forgive Sadeas for that failure. I know it’s irrational, but he should have been there, with Gavilar. Just like I should have been. We both failed our king, and we cannot forgive one another. But the two of us are still united in one thing. We made a vow on that day. We’d protect Gavilar’s son. No matter what the cost, no matter what other things came between us, we would protect Elhokar.

“And so that’s why I’m here on these Plains. It isn’t wealth or glory. I care nothing for those things, not any longer. I came for the brother I loved, and for the nephew I love in his own right. And, in a way, this is what divides Sadeas and me even as it unites us. Sadeas thinks that the best way to protect Elhokar is to kill the Parshendi. He drives himself, and his men, brutally, to get to those plateaus and fight. I believe a part of him thinks I’m breaking my vow by not doing the same.

“But that’s not the way to protect Elhokar. He needs a stable throne, allies that support him, not highprinces that bicker. Making a strong Alethkar will protect him better than killing our enemies will. This was Gavilar’s life’s work, uniting the highprinces…”

He trailed off. Adolin waited for more, but it did not come.

“Sadeas,” Adolin finally said. “I’m…surprised to hear you call him brave.”

“He is brave. And cunning. Sometimes, I make the mistake of letting his extravagant dress and mannerisms lead me to underestimate him. But there’s a good man inside of him, son. He is not our enemy. We can be petty sometimes, the two of us. But he works to protect Elhokar, so I ask you to respect that.”

How did one respond to that? You hate him, but you ask me not to? “All right,” Adolin said. “I’ll watch myself around him. But, Father, I still don’t trust him. Please. At least consider the possibility that he’s not as committed as you are, that he’s playing you.”

“Very well,” Dalinar said. “I’ll consider it.”

Adolin nodded. It was something. “What of what he said at the end? Something about writing?”

Dalinar hesitated. “It is a secret he and I share. Other than us, only Jasnah and Elhokar know of it. I’ve contemplated for a time whether I should tell you, as you will take my place should I fall. I spoke to you of the last words my brother said to me.”

“Asking you to follow the Codes.”

“Yes. But there is more. Something else he said to me, but not with spoken words. Instead, these are words that…he wrote.”

“Gavilar could write?”

“When Sadeas discovered the king’s body, he found words written on the fragment of a board, using Gavilar’s own blood. ‘Brother,’ they said. ‘You must find the most important words a man can say.’ Sadeas hid the fragment away, and we later had Jasnah read the words. If it is true that he could write—and other possibilities seem implausible—it was a shameful secret he hide. As I said, his actions grew very odd near the end of his life.”

“And what does it mean? Those words?”

“It’s a quote,” Dalinar said. “From an ancient book called The Way of Kings. Gavilar favored readings from the volume near the end of his life—he spoke to me of it often. I didn’t realize the quote was from it until recently; Jasnah discovered it for me. I’ve now had the text of the book read to me a few times, but so far, I find nothing to explain why he wrote what he did.” He paused. “The book was used by the Radiants as a kind of guidebook, a book of counsel on how to live their lives.”

The Radiants? Stormfather! Adolin thought. The delusions his father had…they often seemed to have something to do with the Radiants. This was further proof that the delusions were related to Dalinar’s guilt over his brother’s death.

But what could Adolin do to help?

Metal footsteps ground on the rock behind. Adolin turned, then nodded in respect as the king approached, still wearing his golden Shardplate, though he’d removed the helm. He was several years Adolin’s senior, and had a bold face with a prominent nose. Some said they saw in him a kingly air and a regal bearing, and women Adolin trusted had confided that they found the king quite handsome.

Not as handsome as Adolin, of course. But still handsome.

The king was married, however; his wife the queen managed his affairs back in Alethkar. “Uncle,” Elhokar said. “Can we not be on our way? I’m certain that we Shardbearers could leap the chasm. You and I could be back at the warcamps shortly.”

“I will not leave my men, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “And I doubt you want to be running across the plateaus for several hours alone, exposed, without proper guards.”

“I suppose,” the king said. “Either way, I did want to thank you for your bravery today. It appears that I owe you my life yet again.”

“Keeping you alive is something else I try very hard to make a habit, Your Majesty.”

“I am glad for it. Have you looked into the item I asked you about?” He nodded to the girth, which Adolin realized he was still carrying in a gauntleted hand.

“I did,” Dalinar said.

“Well?”

“We couldn’t decide, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said, taking the strap and handing it to the king. “It may have been cut. The tear is smoother along one side. Like it was weakened so that it would rip.”

“I knew it!” Elhokar held the strap up and inspected it.

“We are not leatherworkers, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “We need to give both sides of the strap to experts and get their opinions. I have instructed Adolin to look into the matter further.”

“It was cut,” Elhokar said. “I can see it clearly, right here. I keep telling you, Uncle. Someone is trying to kill me. They want me, just like they wanted my father.”

“Surely you don’t think the Parshendi did this,” Dalinar said, sounding shocked.

“I don’t know who did it. Perhaps someone on this very hunt.”

Adolin frowned. What was Elhokar implying? The majority of the people on this hunt were Dalinar’s men.

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said frankly, “we will look into the matter. But you have to be prepared to accept that this might have just been an accident.”

“You don’t believe me,” Elhokar said flatly. “You never believe me.”

Dalinar took a deep breath, and Adolin could see that his father had to struggle to keep his temper. “I’m not saying that. Even a potential threat to your life worries me very much. But I do suggest that you avoid leaping to conclusions. Adolin has pointed out that this would be a terribly clumsy way to try to kill you. A fall from horseback isn’t a serious threat to a man wearing Plate.”

“Yes, but during a hunt?” Elhokar said. “Perhaps they wanted the chasmfiend to kill me.”

“We weren’t supposed to be in danger from the hunt,” Dalinar said. “We were supposed to pelt the greatshell from a distance, then ride up and butcher it.”

Elhokar narrowed his eyes, looking at Dalinar, then at Adolin. It was almost as if the king were suspicious of them. The look was gone in a second. Had Adolin imagined it? Stormfather! he thought.

From behind, Vamah began calling to the king. Elhokar glanced at him and nodded. “This isn’t over, Uncle,” he said to Dalinar. “Look into that strap.”

“I will.”

The king handed the strap back, then left, armor clinking.

“Father,” Adolin said immediately, “did you see—”

“I’ll speak to him about it,” Dalinar said. “Sometime when he isn’t so worked up.”

“But—”

“I will speak to him, Adolin. You look into that strap. And go gather your men.” He nodded toward something in the distant west. “I think I see that bridge crew coming.”

Finally, Adolin thought, following his gaze. A small group of figures was crossing the plateau in the distance, bearing Dalinar’s banner and leading a bridge crew carrying one of Sadeas’s mobile bridges. They’d sent for one of those, as they were faster than Dalinar’s larger, chull-pulled bridges.

Adolin hurried off to give the orders, though he found himself distracted by his father’s words, Gavilar’s final message, and now the king’s look of distrust. It seemed he would have plenty to preoccupy his mind on the long ride back to the camps.

Dalinar watched Adolin rush away to do as ordered. The lad’s breastplate still bore a web of cracks, though it had stopped leaking Stormlight. With time, the armor would repair itself. It could reform even if it was completely shattered.

The lad liked to complain, but he was as good a son as a man could ask for. Fiercely loyal, with initiative and a strong sense of command. The soldiers liked him. Perhaps he was a little too friendly with them, but that could be forgiven. Even his hotheadedness could be forgiven, assuming he learned to channel it.

Dalinar left the young man to his work and went to check on Gallant. He found the Ryshadium with the grooms, who had set up a horse picket on the southern side of the plateau. They had bandaged the horse’s scrapes, and he was no longer favoring his leg.

Dalinar patted the large stallion on the neck, looking into those deep black eyes. The horse seemed ashamed. “It wasn’t your fault you threw me, Gallant,” Dalinar said in a soothing voice. “I’m just glad you weren’t harmed too badly.” He turned to a nearby groom. “Give him extra feed this evening, and two crispmelons.”

“Yes sir, Brightlord. But he won’t eat extra food. He never does if we try to give it to him.”

“He’ll eat it tonight,” Dalinar said, patting the Ryshadium’s neck again. “He only eats it when he feels he deserves it, son.”

The lad seemed confused. Like most of them, he thought of Ryshadium as just another breed of horse. A man couldn’t really understand until he’d had one accept him as rider. It was like wearing Shardplate, an experience that was completely indescribable.

“You’ll eat both of those crispmelons,” Dalinar said, pointing at the horse. “You deserve them.”

Gallant blustered.

“You do,” Dalinar said. The horse nickered, seeming content. Dalinar checked the leg, then nodded to the groom. “Take good care of him, son. I’ll ride another horseback.”

“Yes, Brightlord.”

They got him a mount—a sturdy, dust-colored mare. He was extra careful when he swung into the saddle. Ordinary horses always seemed so fragile to him.

The king rode out after the first squad of troops, Wit at his side. Sadeas, Dalinar noted, rode behind, where Wit couldn’t get at him.

The bridge crew waited silently, resting as the king and his procession crossed. Like most of Sadeas’s bridge crews, this one was constructed from a jumble of human refuse. Foreigners, deserters, thieves, murderers, and slaves. Many probably deserved their punishment, but the frightful way Sadeas chewed through them put Dalinar on edge. How long would it be before he could no longer fill the bridge crews with the suitably expendable? Did any man, even a murderer, deserve such a fate?

A passage from The Way of Kings came to Dalinar’s head unbidden. He’d been listening to readings from the book more often than he’d represented to Adolin.

I once saw a spindly man carrying a stone larger than his head upon his back, the passage went. He stumbled beneath the weight, shirtless under the sun, wearing only a loincloth. He tottered down a busy thoroughfare. People made way for him. Not because they sympathized with him, but because they feared the momentum of his steps. You dare not impede one such as this.

The monarch is like this man, stumbling along, the weight of a kingdom on his shoulders. Many give way before him, but so few are willing to step in and help carry the stone. They do not wish to attach themselves to the work, lest they condemn themselves to a life full of extra burdens.

I left my carriage that day and took up the stone, lifting it for the man. I believe my guards were embarrassed. One can ignore a poor shirtless wretch doing such labor, but none ignore a king sharing the load. Perhaps we should switch places more often. If a king is seen to assume the burden of the poorest of men, perhaps there will be those who will help him with his own load, so invisible, yet so daunting.

Dalinar was shocked that he could remember the story word for word, though he probably shouldn’t have been. In searching for the meaning behind Gavilar’s last message, he’d listened to readings from the book almost every day of the last few months.

He’d been disappointed to find that there was no clear meaning behind the quote Gavilar had left. He’d continued to listen anyway, though he tried to keep his interest quiet. The book did not have a good reputation, and not just because it was associated with the Lost Radiants. Stories of a king doing the work of a menial laborer were the least of its discomforting passages. In other places, it outright said that lighteyes were beneath darkeyes. That contradicted Vorin teachings.

Yes, best to keep this quiet. Dalinar had spoken truly when he’d told Adolin he didn’t care what people said about him. But when the rumors impeded his ability to protect Elhokar, they could become dangerous. He had to be careful.

He turned his mount and clopped up onto the bridge, then nodded his thanks to the bridgemen. They were the lowest in the army, and yet they bore the weight of kings.