• 11 • The Perils

On the evening of May 4, 1825, the steamer Teche pushed away from the wharf at Natchez, bound for New Orleans, heavily laden with bales of cotton and carrying some seventy passengers, many of whom had boarded the boat at Natchez. Darkness, worsened by a thick haze, quickly descended on the river, and by the time the Teche had traveled but ten miles the boat’s captain decided it was unsafe to proceed farther. He ordered the boat anchored in the stream until conditions improved. About two o’clock the next morning, the haze having dissipated, the anchor was hauled up, and with its steam already raised, the Teche began to move ahead again. Suddenly an explosion that sounded like an artillery bombardment shook the boat, jarring the sleeping passengers from their berths.

All lights aboard the boat immediately went out, extinguished either by the escape of steam or the concussion of the air. In the darkness that instantly followed, a frightened crowd of passengers assembled on the deck, unaware of exactly what sort of disaster had struck them. Then swiftly came a shout that the boat was on fire, and the crowd broke into pandemonium, the panicked passengers rushing helter-skelter about the deck in the darkness, some leaping overboard to escape the flames.

The exact number of lives lost in the Teche disaster was never determined, but several persons were known to have been immediately killed by the explosion, and others were so severely scalded or otherwise injured that they died not long afterwards. No fewer than twenty, and perhaps as many as thirty, persons drowned.

On August 12, 1828, the steamboat Grampus, carrying passengers and towing three sailing brigs and a sloop up the Mississippi to New Orleans, was rocked by an explosion that blasted the captain and a passenger from the wheelhouse and landed them fifty feet away on the forward deck, severely bruised but alive and whole, surrounded by debris. The pilot who had been

145standing at the wheel was thrown into the river and drowned. The boat’s other pilot, who had been walking on the deck just outside the wheelhouse, suffered a broken leg and other injuries and subsequently died. The brig in tow on the larboard side of the Grampus had both topmasts cut off by flying fragments of the Grampus’s machinery, and the brig being towed on the steamer’s starboard side had her bottom penetrated by a piece of the Grampus’s boiler.

Altogether, nine persons lost their lives, some

killed instantly by the blast, some who died later of their

injuries. Four others survived.

The Grampus explosion was determined to

have been the fault of human rather than mechanical failure. The

assistant engineer who was in charge of the engine room while the

chief engineer was off duty had fallen asleep after partly shutting

off the water supply to the boiler, which soon overheated. Awaking,

the assistant engineer quickly noticed that gauges showed the water

at a dangerously low level in the boiler and immediately turned on

the pump to resupply water to the boiler. When the new water

entered the white-hot boiler, it was instantly turned into steam,

creating an excess of pressure that burst the boiler.

On February 24, 1830, one or more boilers of the steamer

Helen McGregor, on its way from New

Orleans to Louisville, exploded while the boat was tied up at the

wharf in Memphis. A section of deck near the boilers was crowded

with people, all of whom were either killed or injured. As many as

sixty persons were believed to have died from the blast, including

an unknown number whose bodies were hurled into the river and never

recovered. The Helen McGregor explosion

was the deadliest in the history of steamboats up till that

time.

On June 9, 1836, near Columbia, Arkansas, the Rob Roy, en route from New Orleans to Louisville,

stopped its engine long enough for the engineer to oil part of its

machinery, and in the two minutes or so that the engine was

stopped, the steam in the boiler accumulated so rapidly that it

burst the boiler. Immediately following the blast, the boat was run

ashore, allowing passengers and crew to escape lest they drown as

the boat burned and sank. The only lives lost were those of the

victims of the explosion itself.

Just after 5 P.M. on November 15, 1849, the Louisiana, an elegant new steamboat captained by

John Cannon, was backing out of its berth at the foot of Gravier

Street in New Orleans, two blocks from Canal Street in the heart of

the business district, when a horrific blast shattered it and blew

the superstructure off the two steamers on either side of it. Human

bodies, persons who had been aboard the Louisiana, were blown two hundred feet into the

air, one of them flew like a projectile through the pilothouse of

the Bostona, one of the steamers docked

beside the Louisiana. People standing

as far as two hundred yards from the boat were struck by flying

debris. With little time for its passengers to escape to shore,

those who had survived the explosion, the broken remains of the

Louisiana quickly sank into the river.

An estimated eighty-six persons lost their lives, including several

who were aboard the two boats beside the Louisiana.

Captain Cannon and his chief engineer, John L. Smith, were ashore

on business at the time of the explosion and came in for much

criticism for their absence. The coroner’s jury that investigated

the disaster determined that the boat’s second engineer, Clinton

Smith, was “grossly, culpably, and criminally neglectful and

careless of his duty.” The jury also reported that Cannon was

“highly culpable” in allowing Clinton Smith to be in charge of the

engine room and blamed Cannon and his chief engineer as the “cause

and causes of said explosion.” In a later hearing, however, both

Cannon and the chief engineer were acquitted of a charge of

manslaughter in connection with the accident.

Starting when the boiler on Henry Shreve’s Washington blew apart in June 1816, the list of

steamboat explosions was long and grim. An estimated seventysix

steamboat explosions on the Mississippi and its tributaries

occurred between 1836 and 1848, a rate of about one every six

months. In the years 1846 to 1848 steamboat explosions on the

western waters were reported to have caused 259

fatalities.

As destructive and deadly as explosions were, fire was the most

fearsome danger. In the early-morning darkness on May 8, 1837, the

Ben Sherrod, running between New

Orleans and Louisville and racing with the steamer Prairie, fell victim to one of the Mississippi’s

worst steamboat fires. About one o’clock in the morning the boat

was about fourteen miles above Fort Adams, Mississippi, racing to

pass the Prairie, just ahead of it. The

firemen were shoving in pine knots and sprinkling rosin over the

coal, doing their best to raise more steam. The boilers became so

hot that they set fire to the sixty cords of wood on board, and the

Ben Sherrod was soon completely

enveloped in flames.

The boat’s yawl was finally launched, but it was so overloaded with

fleeing crewmen that it sank, and nearly everyone in it drowned.

Passengers desperate to escape the fire leaped into the river,

still in their night clothes. Ten women passengers jumped

overboard, some of them quickly drowning once in the water, others

finding floating debris to which they could cling. Only two of the

ten survived.

The Prairie, which the Ben Sherrod was trying to overtake, continued on up

the river without stopping or turning about to try to save those

aboard the stricken vessel. When the Prairie reached Natchez, its captain reported

The Ben Sherrod (the name misspelled by the artist) ablaze on the Mississippi, near Fort Adams, Mississippi. The boat was racing the Prairie when its boilers overheated and set off a fire that consumed the vessel in the early-morning darkness of May 8, 1837. Many of its passengers and crew drowned after leaping into the river to escape the flames (Library of Congress).

that the Ben Sherrod had caught fire and at Vicksburg he made a similar report, for all the good it did.Another steamer, the Alton, which reached the burning boat within half an hour after the fire started, failed to stop to give aid and actually contributed to the accident’s death toll. The Alton came steaming up on the scene, amid the exhausted survivors in the water, holding onto floating debris, and the turbulence caused by its paddle wheel sucked several survivors under water and drowned them. A man holding onto a floating barrel and helping a woman hold on to it, too, was washed underwater by the Alton, as was the woman. The woman drowned; the man bobbed up to the surface and floated fifteen miles downriver before being rescued by the steamer Statesman. A man named McDowell and his wife were both in the river when the Alton arrived. He managed to stay afloat and was swept by the current two miles downriver, where he then swam ashore. His wife, though, holding onto a wooden plank, was pulled under by the Alton and drowned. McDowell’s son also died in the disaster.

Survivors told other stories of horror. A young wife and mother, Mary Ann Walker, awakened by shouts of “Fire!” dashed out of the women’s cabin holding her infant child, trying to reach her husband. Unable to get to him in time, she watched as he fell into the flames and she then jumped into the river to save herself and her child. She grasped a plank and was within forty yards of being rescued by the Columbus, another steamer that had come upon the tragic scene, when she suddenly sank out of sight and was seen no more. A young man who had fled to the hurricane deck and escaped the flames turned back to the blazing cabin when he heard his sister’s cries. Trying to save her, he clasped her in his arms as the flames overtook them. Both burned to death.

One of the Ben Sherrod’s clerks, one of its pilots and its mate all burned to death, as did all the boat’s chambermaids. Of the thirty-five negro crewmen on the vessel, only two survived. Among the dead were two of the captain’s children and his father. The captain’s wife, one of the ten women who leaped into the water, survived but was severely burned. The captain also survived. Not more than six or seven passengers survived. The charred wreck of the Ben Sherrod sank beneath the Mississippi’s dark waters just above Fort Adams.

The steamboat Brandywine left New Orleans in the evening of April 3, 1832, bound for Louisville, carrying some two hundred and thirty passengers as well as freight, including a number of carriage wheels packed in straw and stacked on the boiler deck, near the officers’ cabins. Sometime during its voyage the Brandywine became engaged in a race with the steamer Hudson and fell behind when it was forced to stop for repairs. Back in the race following the repairs, the Brandywine attempted to gain speed and make up its lost time by feeding more rosin into furnace, thereby intensif ying the heat and increasing steam pressure. About thirty miles above Memphis, about seven o’clock in the evening of April 9, the Brandywine’s pilot, in the pilothouse, noticed that the carriage wheels’ straw packing was on fire and quickly gave an alarm.

The captain and crewmen immediately responded, trying desperately to extinguish the flames and pulling out the burning wheels and throwing them overboard. Their efforts, however, only exacerbated the blaze by allowing the wind to whip through the separated mass of straw-packed wheels, spreading the flames to other parts of the boat. In less than five minutes after the pilot had given the alarm, the entire vessel was ablaze. The boat’s yawl quickly filled with frightened passengers and was lowered into the water. No sooner had it touched the stream than it overturned and sank, leaving the passengers to the mercy of the Mississippi.

The pilot steered the flaming steamer, still under way, toward shore, hoping to beach it. About a quarter of a mile from the riverbank the boat ran aground and stuck fast on a sandbar in nine feet of water. Passengers and crewmen still aboard either perished in the flames or hurled themselves into the river and tried to swim to shore. Of the two hundred and thirty passengers the Brandywine carried, an estimated seventy-five survived the disaster. The rest either burned to death or drowned.

The Belle of Missouri was far more fortunate. En route from New Orleans to St. Louis, it stopped just above Liberty, Illinois, to take on wood and caught fire while docked. Its two hundred or so passengers fled safely to shore — and none too soon, for a shipment of gunpowder aboard the boat exploded not long after their escape.

The Clarksville caught fire near Ozark Island in the Mississippi on May 27, 1848, and its pilot promptly turned for shore. Just as the bow of the boat struck the riverbank, flames broke into the main cabin, one of the boilers exploded and, simultaneously, three barrels of gunpowder ignited, creating a huge cloud of black smoke. The captain, named Holmes, jumped overboard with his wife, left her on shore, then returned to the stricken vessel to direct the evacuation of the other passengers, shouting to them, “Pick up chairs, everybody! Jump overboard. But take your chairs. They’ll give you something to hold you up!” When the last person was off the boat, Captain Holmes, suffocating from the pall of smoke, leaped from the upper deck. His body struck the railing on the lower deck, and he was thrown into the flames and burned to death. All of the cabin passengers survived, although many were injured, including the governor of Tennessee. Thirty deck passengers, however, at the stern of the boat and evidently too frightened to dash through the smoke to the bow and jump overboard, lost their lives.

On October 8, 1849, five steamboats — the Falcon, the Illinois, the Aaron Hart, the Marshal Ney and the North America— that were docked at the Poydras Street wharf in New Orleans caught fire and burned as flames spread from boat to boat. Two other steamers in nearby berths managed to back into midstream and escape the inferno with only minor damage.

The Martha Washington, on its way from Cincinnati to New Orleans, caught fire in the Mississippi at one-thirty in the morning on January 14, 1852. Within three minutes the boat was engulfed by flames, blazing from stem to stern. Only a few of the passengers were lost, however, and only one of the crew, the boat’s carpenter.

In the steamboat’s earliest days explosions and fires could be attributed to the crudeness of the propulsion systems, the boilers in particular. It took time for manufacturers and engineers, advancing the steamboat’s machinery largely through trial and error, to learn how to build safe boilers and have them used safely. But as steamers became commonplace and water transportation became the major mover of freight and passengers in the Mississippi valley, competition overtook the concern for safety. Speed became the first objective of steamboat owners and operators. Attempts to beat old records and outrace the competition led to abuses of the machinery and, in many cases, the complete abandonment of caution. Captains would order their boats’ fireboxes crammed with fuel, and fires were made to burn ever hotter by adding to the flames pitch, rosin, oil or pork fat — then tying or weighting down the automatic safety valves on their boilers to raise steam pressure to an explosively high level.

At the same time that newspapers were reporting the latest disasters on the river they were also editorializing against the dangers presented by owners and operators who put speed above safety, widely believed to be the ultimate cause of most steamboat explosions and fires. Letters to the editor further decried the dangerous practices. “Want to know why boilers bust on leaving shore?” one former steamboat captain wrote in a letter published in the New Orleans Picayune in November 1840. “Steamboat men and even passengers have a pride in making a display of speed. To do this they hold on to, instead of letting off, steam. The flue gets hot and the water low, and the first revolution brings the two elements in contact and causes a collapse.”1

Another reason for the alarming number of fiery disasters was thought to be simple disregard of the hazards of traveling with combustible materials aboard a wooden boat. An appalled Frenchman visiting in the United States, Michael Chevalier, wrote that “Americans show a singular indifference in regard to fires. They smoke without the least concern in the midst of halfopen cotton bales, with which a boat is loaded; they ship gunpowder with no more precaution than if it were so much maize or salt pork, and leave objects packed in straw right in the torrent of sparks that issue from the chimneys.”2 Like other critics, Chevalier also noticed that speed trumped all safety considerations aboard the steamers.

Another deadly peril on the river was boat collisions, one of the worst of which involved the steamer Monmouth. It left New Orleans on October 23, 1837, headed for the Arkansas River, carrying 611 Creek Indians to a reservation where they were to be resettled. On the night of October 30, a particularly dark night, the Monmouth was steaming through a part of the Mississippi known as Prophet Island Bend and there encountered the ship Tr e m o n t,3 which was being towed down the river by the steamboat Wa r re n, obscured by the darkness and evidently unseen by the Monmouth’s officers until the last minute. In a desperate effort to avoid the oncoming Tr e m o n t, the Monmouth apparently swerved, but too late. The prow of the Tr e m o n t caught the Monmouth broadsides, smashing into the steamer with such an impact that the Monmouth’s main cabin was separated from its hull. The hull sank almost immediately, but the cabin was sent drifting downstream on the current until it broke in two, spilling all of the Monmouth’s passengers into the night-shrouded river.

The crewmen of the Warren and those of another steamer that arrived on the scene, the Yazoo, managed to save about three hundred of the Monmouth’s passengers from the river. The rest drowned. Also lost were two of the Monmouth’s crew, the fireman and the bartender.

Blame for the collision was placed on the officers of the Monmouth, who failed to observe the Mississippi’s rules of the road. “This boat [the Monmouth],” according to a nineteenth-century account, “was running in a part of the river where, by the usages of the river and the rules adopted for the better regulation of steam navigation on the Mississippi, she had no right to go, and where, of course, the descending vessels did not expect to meet with any boat coming in an opposite direction.”4

On November 19, 1847, the steamer Talisman was approaching Cape Girardeau, Missouri, when it was rammed by the Tempest, which struck it just forward of its boilers. The Tempest backed away, exposing an enormous hole in the Talisman’s side, through which water was rapidly pouring. In the Talisman’s pilothouse the pilot was furiously ringing the engine room bells to order more speed as he headed the vessel for the riverbank, trying to reach it before the boat, quickly sinking, slipped beneath the surface. The engine room meanwhile was filling with water. The chief engineer, named Butler, ordered his strikers to get out of the engine room and seek safety, but refusing orders from the pilothouse to also leave, he remained at his post to keep the crippled steamer under way as long as possible. In less than ten minutes the engine room filled with water, and the Talisman went down, taking chief engineer Butler with it to the bottom of the river. The Tempest stood by to help rescue the Talisman’s passengers and crew, but despite its efforts, more than fifty of those aboard the Talisman lost their lives.

The Archer, operating out of St. Louis, was struck by the steamer Di Vernon five miles above the mouth of the Illinois River on November 27, 1851, and was cut in two. It sank in three minutes, taking forty-one lives.

A twentieth-century writer gave some understanding of the problem of collisions on the river, particularly collisions involving towboats, which tow barges or other vessels by pushing them, making of them an unwieldy burden:

When you come to consider it, there should be more collisions than there are on the river. Especially on some of the smaller tributaries, the bends are so sharp that there is no way to see around them; and the hills go up on both sides, hiding any trace of smoke that may warn a pilot of another tow. You might hear the other fellow’s whistle, and then again you might not. It depends on the wind and the noises on your own boat.... The emergencies on the river are awful in their slowness. You see them a long time ahead and you do what you can; and if that’s not good enough, you’ll wish you hadn’t ever come on the river, and you wait for the crash — ten or fifteen minutes with no way out, no way to stop it from happening.5

Other vessels, though, were not the only potentially disastrous hazards that steamers encountered on the river. On January 3, 1844, the Shepherdess was ascending the Mississippi on its way to St. Louis from Cincinnati, steaming into the stormy winter night through frigid water, most of its seventy or so passengers asleep, though several in the men’s cabin chose to huddle around the stove to keep warm. Around eleven o’clock, without any warning, the boat plowed into a snag — an obstruction in the river, usually a fallen tree — near Cahokia, Illinois, ramming it with such force that several planks were torn from the forward part of the boat’s hull. Water instantly began rushing into the gaping hole and in less than two minutes the water had risen to the lower deck. The captain, A. Howell of Covington, Kentucky, who had recently bought the Shepherdess and was making his first trip on it, ran to the women’s cabin to reassure the ladies, telling them there was no danger, then returned to the forecastle, which was awash as the bow of the vessel was slipping beneath the surface. He later was apparently swept overboard by the rising water and drowned.

Within three minutes the water had reached the upper deck, and passengers there could see from the stern railing people in the river, struggling to stay afloat in the icy stream. Some passengers on the lower deck had been able to save themselves by climbing into the yawl, which they cut loose as the water rose and, finding no oars in it, paddled it to shore with a broom. The only safe place left aboard the vessel was the hurricane deck, but it became difficult to reach as the boat’s bow sank deeper into the river. The only way to get to it was from the stern. Most, if not all, of the passengers that had been in the main cabin, on the boiler deck, managed to reach the roof of the hurricane deck. Some of them were aided by passenger Robert Bullock, a young man from Maysville, Kentucky, who with little regard for his own safety went from stateroom to stateroom and whenever he heard a young child crying he took the child and handed him or her up to someone on the hurricane deck. Among those he helped save was the so-called Ohio Fat Girl, a 440-pound woman who was a member of a carnival troupe.

The powerless vessel, carried downstream by the current, crashed into a second snag, this rising one above the surface. The boat nearly capsized when it struck the snag, tipping over on its larboard side, then lurching to starboard, and spilling a number of passengers into the icy river, only some of whom were able to swim to shore. The boat righted itself and continued to drift downstream, then struck the riverbank so hard that the cabin was separated from the hull. The hull then sank on a sandbar; the cabin continued a short distance and it, too, hit a sandbar and became stuck.

The steamer Henry Bry had stopped at Carondelet, just below St. Louis, and as the cabin of the Shepherdess floated past its position, the Henry Bry’s captain ordered his yawl launched into the river to rescue as many as he and his crewmen could by making repeated trips to haul survivors to safety. The ferryboat Icelander came down from St. Louis to join the rescue effort around three A.M. and removed all the remaining survivors from the Shepherdess’s marooned cabin. An estimated forty persons, many of them young children, failed to survive the disaster.

Snags and other objects in the river had been a menace ever since the first steamboat on the Mississippi, the New Orleans, had its hull pierced by a stump and sank in 1814. Another early victim was the Tennessee. Steaming upriver through a snowstorm, its pilothouse windows coated with snow and its pilot unable to see through them, it ran into a snag near Natchez on the night of February 8, 1823, and had a hole the size of a door torn in its hull. Its yawl was lowered into the water and it took one load of passengers to shore, but with only one oar to propel it, it made just one trip. Many of the passengers and crewmen who were left aboard jumped into the river when they felt the boat going down. Some found floating wreckage to cling to until they could be rescued by skiffs that were rowed out from shore to save them. The rest were not so fortunate. Sixty persons were lost to the river.

The steamer John L. Avery left New Orleans on March 7, 1854, and about forty miles below Natchez on March 9, while it was apparently racing another steamer, it struck what was believed to be a tree that had been washed into the river by a recent rain. Water immediately rushed into the boat’s hold through the pierced hull. The boat’s carpenter and J.V. Guthrie, one of the engineers, were standing just forward of the boilers when the crash occurred, and the carpenter dashed to the hold to assay the damage, but the water was pouring in too fast to do anything about the leak, and the carpenter had to quickly retreat back to the deck. Guthrie then hurried for the engine room, but the water was up to his knees before he reached it. The cabin passengers quickly sought refuge on the hurricane deck. Minutes later the hull separated from the cabin and went down in sixty feet of water.

Six persons who had remained in the main cabin were rescued by the captain, J.L. Robertson, and the boat’s two clerks, who lifted them from the rising water through a skylight onto the hurricane deck. One of those pulled through the skylight was a woman with one of her children her arms. She

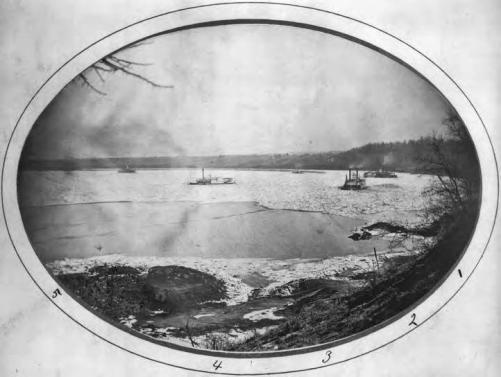

The ice gorge that trapped five steamers in the Mississippi between Cairo, Illinois, and Columbus, Kentucky, in February 1872. Along with explosions, fires, collisions and snags in the river, ice, which could rip open a hull and sink a vessel, was one of the perennial perils for steamers on the upper Mississippi (Library of Congress).

had to be restrained from plunging back into the cabin, nearly filled with water, to rescue her baby, who had been asleep on the woman’s bed. Many of the deck passengers were trapped by freight on the main deck and drowned as the boat sank. The second mate and another person launched the steamer’s yawl, but it was almost immediately turned over by panicked passengers fleeing the doomed vessel. Twelve of the boat’s twenty firemen drowned. Witnesses told of seeing struggling passengers and crewmen in the river, going down one by one in the murky water. At least eighty persons lost their lives in the John L. Avery disaster.

On the upper Mississippi ice was a hazard that claimed several steamers, including the Iron City, crushed by ice in the river at St. Louis on December 31, 1849; the Northern Light, which struck ice along the shore about 1862; the Fanny Harris, sunk by ice in 1863; and the Metropolitan, sunk by ice at St. Louis on December 16, 1865. Rocks were another peril. The J.M. Mason struck a rock that sank it in 1852, and the H.T. Yeatman ran into rocks and sank at Hastings, Minnesota, in April 1857. Sandbars were often no worse than a hindrance when steamboats ran onto them, but sometimes they would sink a boat, as one did to the Kentucky No. 2, which sank on a sandbar near Prescott, Wisconsin. In some cases the boat that had hit a sandbar was not sunk but simply left hopelessly stranded, unable to be lifted or pulled off, doomed to become a derelict after its passengers and crew had been removed from it.

One of the oddest river hazards was encountered by the steamer Baltimore. In 1859 it had the misfortune of running onto the underwater wreck of the steamboat Badger State, which had sunk three years earlier. With its hull opened up by the submerged vessel’s superstructure, the Baltimore quickly went down, so fast that it settled atop the hulk of the Badger State.

Bridges were — and still are — a potential hazard to steamboat navigation. The captain of the modern excursion boat Mississippi Queen, replying to a passenger’s question about the worst danger he faced on the river, said it was bridges that presented the biggest concern. If the boat should strike a bridge at a bad angle, there was a great danger that the boat, top heavy as it is, would capsize. The danger posed by bridges has existed since 1856, when the first bridge across the Mississippi River was completed after three years of construction. It was a railroad drawbridge that spanned the river between Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa. It consisted of three parts — a bridge over what is a narrow channel that passes between the Illinois shore and an island in the river (Rock Island), a section of track that ran across the island, and a long bridge over the wider part of the river, between the island and the Iowa shore. The placement of the bridge was disadvantageous for boats, for at that spot, there were cross-currents and boils produced by the chain of rocks in the river, all of which made boat navigation there a pilot’s challenge.

When it was proposed, the bridge met powerful opposition from steamboat interests, who argued that it would be a hazard to navigation, and from the United States secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, who issued a ruling prohibiting its construction on the grounds that it would cross a government reservation. Nevertheless, it was built, the railroad interests proving more powerful than those who opposed the bridge.

On the morning of May 6, 1856, fourteen days after the first train had chugged across the newly completed bridge, the steamer Effie Afton passed under the bridge’s draw and when it was some two hundred feet above the bridge, its starboard paddle wheel inexplicably stopped, and the boat turned, swung back and crashed into one of the bridge’s piers. The impact apparently knocked over the stove in the Effie Afton’s galley, starting a fire that rapidly spread over the boat, destroying it and a section of the bridge as well. A number of lives were lost.

The Effie Afton’s owners swiftly sued the bridge company for damages. Suspecting that sympathy for the steamboat owners and for the Effie Afton’s victims would be strong, the directors of the bridge company carefully chose a lawyer who could persuasively argue their case. The man they picked was a forty-seven-year-old lawyer from Sangamon County, Illinois, who had been recommended to them as “one of the best men to state a case forcibly and convincingly, with a personality to appeal to any judge or jury hereabouts.” His name was Abraham Lincoln.

The case went on the docket as Hurd vs. Railroad Bridge Company and was tried before Justice John McLean in Circuit Court in September 1857. Lawyers for the steamboat company presented two main arguments. One, that the Mississippi River was the great waterway for the commerce of the entire Mississippi valley and it could not be legally obstructed by a bridge. And two, the bridge involved in the accident was so situated in the river’s channel at that point that it constituted a peril to all water craft navigating the river and it formed an unnecessary obstruction to navigation.

Lincoln argued that “one man had as good a right to cross a river as another had to sail up or down it.” He asserted that those rights were equal and mutual rights that must be exercised so as not to interfere with each other, like the right to cross a street or highway and the right to pass along it. From the assertion of the right to cross the river, Lincoln moved on to the means of crossing it. Must it always be by canoe or ferry? he asked rhetorically. Must the products of the vast fertile country west of the Mississippi be forever required to stop at the west bank of the river, there to be unloaded from railway cars and transferred to boats, then reloaded onto cars on the east side of the river? The steamboat interests, he argued, ought not to be able to so hinder the nation’s commerce and to stifle the development of the extensive area of the country that lay west of the Mississippi.

Lincoln conceded that the currents at the site of the bridge were problematic, but on the fourteenth day of the trial he presented a model of the Effie Afton and used it to show the jury, with the support of witnesses’ testimony, how the accident occurred and to contend that it was the fault of those in command of the Effie Afton, that the boat had altered its course from the safe channel in order to pass another steamer, the Carson, which was also ascending the river. “The plaintiffs have to establish that the bridge is a material obstruction,” he declared in his closing argument, “and that they have managed their boat with reasonably care and skill.”

The jury apparently did not think the Effie Afton’s owners had made the case Lincoln said they must. The jury failed to agree on a verdict and was discharged.

On May 7, 1858, a St. Louis steamboat owner, James Ward, filed a petition in the U.S. District Court of the Southern Division of Iowa asking that the bridge be declared a nuisance and that the court order it removed. The federal district judge, John M. Love, so ordered, but on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court in December 1862 the order was overturned and the bridge was allowed to remain. Complaints about the bridge continued to come from steamboat owners and captains, to the point that in 1866 the United States Congress passed an act requiring the Rock Island bridge to be dismantled and replaced by a new one farther up the river, the cost of which was to be shared by the railroad and the United States government. The new bridge, erected just above Rock Island, was completed in 1872, and the old one was torn down.

Bridge laws enacted by Congress in the 1870s allowed railroads to build bridges at locations specified in the enactments, but the bridges were required to be of a design and style of construction that would avoid serious obstructions to river navigation.

As for the other steamboat perils, a spokesman for the steamboat industry, William C. Reffield, evidently seeking to avoid further regulation, assured the United States secretary of the treasury, “The magnitude and extent of the danger to which passengers in steamboats are exposed, though sufficiently appalling, is comparatively much less than in other modes of transit with which the public have been long familiar.... It will be understood that I allude to the dangers of ordinary navigation [on the seas], and land conveyances by animal power of wheel carriages. In the former case, the whole or greater part of both passengers and crew are frequently lost, and sometimes by the culpable ignorance or folly of the officers in charge, while no one thinks of urging a legislative remedy for this too common catastrophe. In the latter class of cases, should inquiry be made for the number of casualties occurring ... and the results fairly applied to our whole population and travel, the comparatively small number injured or destroyed in steamboats would be a matter of great surprise.”6

Even so, the steamboat trade publication Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory in 1856 listed eighty-seven major disasters that had occurred on western rivers up to that time, many of which had each claimed a hundred or more lives. Also listed were 220 “minor disasters,” as the publication called them. Between 1811, when the first steamboat descended the Mississippi, and 1850, at the midpoint of the golden age of the Mississippi River steamboat, steamboat accidents on the Mississippi killed or injured more than four thousand people.7

By far the worst catastrophe on the Mississippi, the deadliest maritime disaster in the nation’s history to this day, taking more lives than did the Titanic, was the tragic loss of the steamer Sultana. It was a large — two hundred and sixty feet long, forty-two feet in the beam — handsome side-wheeler that had been launched at Cincinnati on January 3, 1863. It had been built for Captain Preston Lodwick, owner of three other steamboats, who paid $60,000 for it and who within the first year of the boat’s operation had made more than twice that amount carrying freight and Union troops under contracts with the U.S. government.

It was equipped with four tubular boilers arranged horizontally and parallel to one another. The boilers were of a kind rarely used on the muddy Mississippi, because the mud carried by the river water, which was drawn into the boilers to produce steam, accumulated not in mud drums but in the two dozen five-inch-wide flues (or tubes) inside each boiler, necessitating frequent cleaning of the flues to prevent them from clogging and bursting.

The Sultana was built to accommodate seventy-six cabin passengers — the first-class passengers who occupied the staterooms — and three hundred deck passengers. Its legal capacity, then, was three hundred and seventy-six, plus the eighty to eighty-five members of the crew.

The boat’s captain was thirty-four-year-old Cass Mason, who with two partners had bought the Sultana from Lodwick for $80,000 on March 7, 1864. Mason had first become a captain after marrying Mary Rowena Dozier, daughter of Captain James Dozier, who owned several steamers, including one named Rowena, which Dozier gave Mason to command. Mason apparently decided to use his new position to make a little money on the side by dealing in contraband, at which he was caught red-handed. On a trip downriver the Rowena was stopped by a Union gunboat on February 13, 1863, near Island No. 10 in the Mississippi and had its cargo searched. The search revealed a quantity of quinine destined for Tiptonville, Tennessee, then held by Confederate forces, and three thousand pairs of Confederate uniform pants. The gunboat’s commander confiscated the cargo and the Rowena, which the U.S. Navy added to its river fleet and which was permanently lost to Dozier when it struck a snag near Cape Girardeau and sank two months after being seized. Mason managed to avoid arrest, but not the wrath of his father-in-law, who refused to have any further business dealings with him.

Since becoming part owner of the Sultana, Mason had evidently incurred more financial problems, for by early April 1865 he had sold most of his share in the boat, reducing his interest from three-eighths to one-sixteenth.

On April 9, 1865, the day that General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Grant at Appomattox Court House, the Sultana, with a full load of passengers aboard, docked at St. Louis, having just ended its voyage from New Orleans. Three days later it turned around in the river and began its return trip to the Crescent City. It arrived at Cairo about one o’clock the next morning, April 13. While it still lay docked there, on the evening of April 14, John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln in Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. The following morning, the same morning that the president died of his wound, the Sultana shoved off from the wharf at Cairo and resumed its downriver run.

The Sultana arrived at Memphis on the morning of April 16 and departed that same morning, on its way to Vicksburg. Near Vicksburg, at Camp Fisk, a large number of Union soldiers who had been recently released from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps were waiting to be shipped to Camp Chase, Ohio, near Columbus, and Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, near St. Louis, to be mustered out of the Army before being allowed to return to their homes. The U.S. Army would pay five dollars for each enlisted man and ten dollars for each officer to be transported from Vicksburg to those two destinations. Learning about the released POWs, Mason determined to get a boatload of those veterans as passengers on the Sultana. They represented a potential boon to him — perhaps a partial solution to his money problems. Moreover, he figured the Sultana was entitled to a load of those passengers because it was one of the steamers of the Merchants’ and People’s Line, an organization of independently owned steamboats that had been formed two months earlier and that held U.S. government contracts to transport freight and troops.

No sooner had the Sultana docked at Vicksburg than Mason was talking to Lieutenant Colonel Reuben B. Hatch, chief quartermaster for the U.S. Army’s Department of Mississippi, about picking up his share of military passengers when the Sultana made its return trip from New Orleans. Hatch assured him the Sultana would get some of the troops.

The Sultana arrived at New Orleans on April 19. At about ten o’clock in the morning on Friday, April 21, with seventy-five passengers aboard, as well as a hundred live hogs and sixty mules and horses and other cargo, it backed away from the Gravier Street wharf and began its voyage upstream. The river, running high, was swollen with the waters of the usual spring run-off from melting snow and ice in the northern reaches of the Mississippi and its tributaries. In many places it had surged out of its banks and was streaming southward wide, fast and cold.

With ten hours to go before the Sultana was scheduled to reach Vicksburg, its chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, noticed steam escaping from a crack along a seam in one of the boilers of the larboard engine. He decided the Sultana could continue on to Vicksburg, but at a slower speed, and that repairs would have to be made at Vicksburg, where the boat had had to undergo boiler repairs once before.

It reached Vicksburg in the late afternoon on April 23, and Wintringer hustled ashore to find R.G. Taylor, a Vicksburg machinist, and have him assay the boiler problem. Taylor obligingly went aboad and upon inspection of the boilers, found a bulge in the seam of the middle larboard boiler. He asked Wintringer why the boiler hadn’t been repaired before the boat left New Orleans (an indication perhaps of the danger he believed the bulge presented). Wintringer replied that the boiler was not leaking when the vessel was at New Orleans.

Captain Mason then entered the conversation and instructed Taylor to fix the bulging seam as quickly as he could. Taylor responded that to do the job right, he would have to replace two of the boiler’s iron sheets and, apparently encountering some resistance, said that if he were not allowed to make the repairs he felt were necessary, he would make no repairs at all. He then turned and strode off the boat.

Right behind him went Wintringer and Mason, explaining their concern over the amount of time that it would take to replace the two sheets and asking Taylor instead to do the best he could within reasonable time constraints. Mason promised Taylor that when the Sultana reached St. Louis, he would make the more extensive repairs that Taylor said were needed. But for now, he urged Taylor, for the sake of time, to simply rivet a patch onto the boiler to take care of the leak. Charmer that he was, he at last persuaded Taylor. A metal patch twenty-six by eleven inches and a quarter-inch thick would be applied to the faulty boiler. The patch would be thinner than the iron sheets that formed the boiler, which were one-third of an inch thick. Taylor’s idea was to smooth out the bulge first, then apply the patch. He was talked out of that and instead was asked to attach the patch over the bulge.

Time was the big consideration for Mason. He knew that those released prisoners of war were waiting for transportation, and he was apparently worried that he might lose his share of them if the Sultana were delayed too long. Major General Napoleon J.T. Dana, commander of the Army’s Department of Mississippi, had made known that he wanted those veterans returned home as soon as possible, and two steamers, the Henry Ames and the Olive Branch, had already embarked a load of them and left Vicksburg earlier that day. The Sultana had to be repaired quickly, lest all the troops depart by the time lengthy repairs were done. Those potential passengers had become extremely important to Captain Mason.

Mason wasn’t the only one whose mind was on something other than safety and the welfare of the soldiers who were to become passengers. The U.S. Army officers in charge of the arrangements for transporting the men were showing their own lack of good judgment. Despite the availability of other steamers, including the Lady Gay, another Merchants’ and People’s Line steamer, which had a greater capacity than the Sultana but had been refused any of the soldiers, and the Pauline Carroll, which sat virtually empty at the Vicksburg waterfront, all of the estimated 2,400 released soldiers were crammed onto the Sultana. First came 398 soldiers who had just been released from the nearby Army hospital. Then came the first trainload, about 570 men. Then came a second trainload, about 400 men. Then came a third trainload, about 800 men. And all the while, despite gentle protests that the Sultana was being overloaded and that the Pauline Carroll was standing there empty and ready to go, the officers in charge, Army captain George Williams, the U.S. officer in charge of the U.S.-Confederate exchange of prisoners, and Army captain Frederic Speed, temporarily in charge of the released Union prisoners, refused to put any of the men aboard any boat other than the Sultana.

Williams claimed that the Pauline Carroll had offered a bribe of twenty cents per man to get the former POWs as passengers and for that reason it could not have a single one of them. Besides, he said, “I have been on board [the Sultana]. There is plenty of room, and they can all go comfortably.”

The loading continued on into the darkness of April 24, and when all were aboard, the Sultana was literally loaded to the gunwales, from stem to stern. A long row of double-decker cots was set up through the center of the saloon to provide beds for the officers. The enlisted men, the great mass of the troops, had at first been assigned sections of the boat according to their units, the men of the Ohio regiments going to the hurricane deck and filling it, the men of the Indiana regiments going to the boiler deck, encircling the cabin, but as the day had worn on and the troops waiting on the wharf mingled with one another, order and control were lost, the rolls becoming confused and the men allowed to claim space aboard the boat wherever they could find it, men from Michigan, Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia, most in their early twenties, many looking like skeletons from their months of starvation at the Cahaba and Andersonville prison camps, all eager to get home after having survived the ordeals of the war and the camps.

They filled the main deck, they crowded the hurricane deck, they climbed and took over the roof of the texas deck, the mass of their bodies so heavy that William Rowberry, the Sultana’s first mate, directed a work party of deckhands to wedge stanchions between the boiler deck and the hurricane deck to prevent the sagging upper decks from collapsing.

To sleep, the troops would have to lie down anywhere they could, on the steps of companionways, beside the engine room, most on the open decks, stretched out like pieces of cordwood beside one another. In the absence of restrooms, they would contort themselves over or under the boat’s rails to relieve themselves.

William Butler, a cotton merchant from Springfield, Illinois, who from the deck of the Pauline Carroll watched the third trainload of troops board the Sultana, reported the troops’ reaction: “When about one third of the last party that came in had got on board, they made a stop, and the remainder swore they would not go on board. They said they were not going to be packed on the boat like damned hogs, that there was no room for them to lie down, or a place to attend to the calls of nature. There was much indignation felt among them, and among others who went about the boats. Some person on the wharf boat, an officer I presume, ordered them to move forward and they went on board.”8

About nine o’clock in the evening on April 24 the Sultana at last backed away from the Vicksburg wharf and resumed its northward voyage, the men making the best they could of their miserable situation, which must have seemed but an extension of the horrors they had suffered in the prisoner-ofwar camps. Through two nights and two days they endured as the Sultana steamed northward toward home.

About one o’clock in the morning of Thursday, April 27, 1865, having loaded aboard enough coal to get it to Cairo, the Sultana pulled away from the coaling station at Memphis and again headed upstream, into a particularly dark night and misting rain. All was quiet on the decks, in the saloon and in the staterooms, almost all of the passengers and most of the crew deep in slumber as the lights of Memphis receded and disappeared. About seven miles above Memphis the Sultana approached a group of marshy islands called Paddy’s Hen and Chicks. Ordinarily the river at this spot was three miles wide, but now, swollen with floodwaters, it was three times that width, its waters covering both banks.

At one-forty-five the Sultana passed one of the Chicks, island No. 41, near the Arkansas side of the river. After that came Fogelman’s Landing. It was now two o’clock.

Suddenly the Sultana erupted in a massive explosion, as if struck by a thunderous earthquake, shattering the vessel, blasting a chasm in the superstructure above the boilers, spraying deadly scalding steam over passengers, blowing parts of the upper decks to fragments and shooting them and passengers high into the night sky, toppling the two chimneys, hurling most of the pilothouse from its perch atop the texas, scattering debris and human bodies, many broken and dead, others still alive but gravely injured, into the cold, dark, surging river. Burning coals, blasted from the vessel’s fireboxes,

The ill-fated steamer Sultana, victim of the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history, photographed at Helena, Arkansas, on April 26, 1865. Early the next morning, as it steamed northward from Memphis, crammed with Union soldiers recently released from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps, it exploded and burned, taking more lives than did the Titanic (Library of Congress).

rose like fireworks into the air and rained back down on the wooden decks and superstructure, setting them alight. Within minutes the shattered Sultana was engulfed in flames.

From everywhere came the cries, shouts, shrieks and panicked screams of desperate passengers, scalded, burned or critically injured, many trapped beneath wreckage, unable to save themselves or be saved. Soon many hundreds faced the horror of being burned alive or escaping the flames by jumping into the dark and deadly river. Nearly all who were able chose the river. The badly injured and the horribly scalded begged their fellow passengers to lift them and throw them overboard, which some did. The river within yards of the boat quickly became a seething mass of struggling humanity, individuals bobbing so tight together it became impossible for more escaping passengers to leap into the water without landing first on those who had jumped before them. Those unable to swim grasped at anything, anyone within reach, and many went down to their deaths in the frantic grip of each other.

The exact total number of the Sultana’s victims remains uncertain, because the number of military passengers aboard is in dispute, as is the number of survivors. Many — perhaps three hundred or more — who were admitted to hospitals and were initially counted as survivors died of their burns or injuries within days after being hospitalized. The estimates of the total number of victims, military and civilian, range from 1,238 (the estimate of Brigadier General William Hoffman, who conducted an inquiry immediately following the disaster) to 1,547 (the estimate made by the U.S. Customs Department at Memphis) to 1,800 or more (calculated from the varied estimates of the number of survivors, which ranged from fewer than 500 to around 800).9 The likelihood is that the higher estimates of victims are more accurate.

The boat itself, “a massive ball of fire,” as an eyewitness on shore described it, drifted downriver and became lodged against one of the Chick islands near Fogelman’s Landing, just above Mound City, Arkansas. There it sank, its charred remains eventually buried beneath the river’s sediment. In the years since, the river, as if abhorring any reminder of the disaster, shifted its course three miles to the east of Mound City, and the Sultana’s grave is now unknown, lying somewhere in an Arkansas farm field.

The cause of the explosion is likewise unknown. An investigation, ordered by Major General Cadwallader C. Washburn, commander of the U.S. Army’s District of West Tennessee, yielded an official report, made public on May 2, 1865, that declared the cause was insufficient water in the boilers. General Dana, commander of the Army’s Department of Mississippi, the man who had ordered the released prisoners sent home as soon as possible, also held an investigation, which, like Washburn’s, had more to do with the overloading of military passengers aboard the Sultana than it did with the circumstances of the explosion. On April 30, the U.S. secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, ordered the commissary general of prisoners, Brigadier General William Hoffman, to conduct an additional investigation. Hoffman’s report concluded that there was not enough evidence to establish the cause of the explosion, but that the evidence did suggest that insufficient water in the boilers was the cause.

And there, insofar as the Army was concerned, the matter rested. Claims that Confederate saboteurs had placed explosives aboard the Sultana were apparently never seriously considered by the investigators. There is no mention of such in the testimony given to the investigators, and nothing in the investigators’ inquiries indicates sabotage was even suspected.

The relevant civilian authority, J.J. Witzig, the supervising inspector of steamboats for the area that included St. Louis, faulted the patch riveted onto the leaking boiler and put the blame for allowing it on the Sultana’s chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer. Witzig, however, conceded that the tubular boilers were part of the problem.

In the end, no one was held accountable for the Sultana disaster. The guilt was eventually assigned to the design of the boilers. After the Walter R. Carter, equipped with tubular boilers like the Sultana’s, blew up later in 1865, killing eighteen people, and the Missouri, similarly equipped, exploded the next year, killing seven, the offending boilers were removed from all steamers traveling south of Cairo.