The Start

It was the most massive crowd on Canal Street since Mardi Gras, despite the summer heat, which afternoon clouds and a light shower failed to abate. The Daily Picayune reporter covering the event observed that the city seemed to empty itself onto the levee, thousands of onlookers thronging to where New Orleans’s famous thoroughfare meets the mighty river. The St. Louis Republican reporter in town for the event said the levee in the area of Canal Street was so densely packed with people that there was practically a solid human mass from the river back a hundred yards or so to the first row of buildings.

In upper-floor windows, on rooftops and on lacy iron balconies people assembled to watch the spectacle. Seven blocks away from the river, on St. Charles Street, as many as a dozen desperate onlookers climbed atop the dome of the St. Charles Hotel to get a clear view of the expected action. As far as the eye could see and farther, from Canal Street all the way uptown to Carrollton and beyond, eager spectators spread themselves out along the river’s edge, standing or sitting, squatting or lying wherever they managed to find viewing space, passing the time with food and drink bought from street vendors, suffering the crush gladly, knowing they were about to witness one of history’s great moments.

Some spectators, bent on a close-up view of the racers, boarded steamers that had scheduled special excursions to carry paying customers as far as twenty miles up the river, following the boats as the race proceeded. The steamer Henry Tate had moved to an upriver vantage point, carrying on board a load of passengers, who had shelled out a dollar apiece for tickets, and a brass band to further enliven the festive atmosphere. A half dozen or so other steamers had joined the Henry Tate, all providing the river’s equivalent of ringside seats.

Through the courtesy of the Mississippi Valley Transportation Company, the Picayune reporter became one of the passenger-spectators aboard

The New Orleans riverfront in the mid– 1800s. By 1860 New Orleans had become the largest export shipping point in the world. In 1870, at the time of the historic steamboat race, it was still the No. 1 steamboat port in the nation (Library of Congress).

the steam tug Mary Alice, which, like the other vessels, stood in the river waiting for the race to begin. Looking out over the broad expanse of water and across it toward the clusters of buildings in Algiers on the west bank, and noticing where the river lapped the muddy edge of the east bank nearby, the reporter could see that the river was low, as it had been for the past several days. He reported it at six feet and four inches below the high-water mark set eight years earlier.

Steamboat activity at the New Orleans riverfront on this day was not so bustling as it once had been, during the bygone golden days of Mississippi River steamboats, but activity was not exactly languid. Steamboats — and cotton — had helped New Orleans become, by 1860, the largest export shipping point in the world, and in 1870 it was still the No. 1 steamboat port in the nation. Eight packets — as mail- and passenger-carrying steamboats were called — had arrived in the past twenty-four hours and were docked bow-first into the wharves, side by side, like gigantic animals feeding at a trough. The Mayflower and the Wade Hampton had come from the Ouachita River, the Bradish Johnson from Shreveport, the Hart Able and W.S. Pike from Bayou Sara, the John Kilgour from Vicksburg, and the Enterprise and B.L. Hodge from the Red River. Other packets, including the Mary Houston and the Great Republic, having arrived earlier, still lay at the wharf, taking on passengers and freight and due to depart on Saturday.

Three departures were scheduled for this day: the Robert E. Lee, which had advertised that it was bound for Louisville, but which no one believed it was; the Natchez, bound for St. Louis, as everyone knew; and the Grand Era, bound for Greenville, Mississippi. The Natchez’s usual run was between New Orleans and St. Louis. The usual run of the Robert E. Lee was between New Orleans and Louisville. Ordinarily those two boats never left New Orleans on the same day. But on this day, Thursday, June 30, 1870, they were going to do something out of the ordinary.

The customary departure time for steamboats leaving New Orleans was between four and five P.M., and their leaving invariably created a riverfront scene that, having once been witnessed, remained a vivid impression on those who had experienced it. The onetime steamboat pilot Samuel L. Clemens of Hannibal, Missouri, who quit steamboating and became author Mark Twain, long remembered the sights and sounds of the New Orleans waterfront departure scene and described them for the readers of his classic work, Life on the Mississippi:

From three [ P.M.] onward they [the steamboats] would be burning rosin and pitch-pine (the sign of preparation), and so one had the picturesque spectacle of a rank, some two or three miles long, of tall, ascending columns of coal-black smoke; a colonnade which supported a sable roof of the same smoke blended together and spreading abroad over the city.

Every outward-bound boat had its flag flying at the jack-staff, and sometimes a duplicate on the verge-staff astern. Two or three miles of mates were commanding and swearing with more than the usual emphasis; countless processions of freight barrels and boxes were spinning athwart the levee and flying aboard the stage-planks; belated passengers were dodging and skipping among these frantic things, hoping to reach the forecastle companionway alive...; women with reticules and bandboxes were trying to keep up with husbands freighted with carpet sacks and crying babies...; drays and baggage-vans were clattering hither and thither in a wild hurry, every now and then getting blocked and jammed together...; every windlass connected with every fore-hatch, from one end of that long array of steamboats to the other, was keeping up a deafening whizz and whir, lowering freight into the hold, and half-naked crews of perspiring negroes that worked them were roaring such songs as “De Las’ Sack! De Las’ Sack!”... By this time the hurricane and boiler decks of the steamers would be packed black with passengers. The “last bells” would begin to clang, all down the line...; in a moment or two the final warning came — a simultaneous din of Chinese gongs, with the cry, “All dat ain’t goin’, please to git asho’!”... People came swarming ashore, overturning excited stragglers that were trying to swarm aboard. One more moment later a long array of stage-planks was being hauled in....

Now a number of the boats slide backward into the stream, leaving wide gaps in the serried rank of steamers.... Steamer after steamer straightens herself up, gathers all her strength, and presently comes swinging by, under a tremendous head of steam, with flag flying, black smoke rolling, and her entire crew of firemen and deck-hands (usually swarthy negroes) massed together on the forecastle ... all roaring a mighty chorus, while the parting cannons boom and the multitudinous spectators wave their hats and huzza! Steamer after steamer falls into line, and the stately procession goes winging its flight up the river.1

As five o’clock approached, the clamor of departure on this day seemed even more boisterous than what Clemens remembered. Two of the steamboats about to shove off from the wharf were going to commence the most

Steamboats lined up at the New Orleans wharves around 1870. Mark Twain captured the excitement of such New Orleans riverfront scenes in his classic work, Life on the Mississippi (Library of Congress).

promoted, most talked about, most speculated over, most gambled on steamboat race in history.Everyone along the river, in towns, villages and cities and the spaces in between them, had heard about it, as had a great many in cities far from the banks of the Mississippi, across the country and across the seas. The race had captured the attention and imagination of almost everybody. And most of those nestled in the huge crowd of spectators, white and black, employer and employee, rich and poor, man and woman, boy and girl, had a favorite they were pulling for. All were expecting to see the beginning of the race of the century, pitting two of the biggest, speediest and best-known packets against each other, the Natchez versus the Robert E. Lee, running from New Orleans to St. Louis, twelve hundred river miles, as fast as their huge paddle wheels — and their captains — could drive them.

The early-twentieth-century steamboat historians Herbert and Edward Quick, who lived at a time that was close to America’s steamboating era, evinced the feelings of many people of those days:

To those who merely looked on, a steamboat race was a spectacle without an equal. To the people of the lonely plantations on the reaches of the great river, the sight of a race was a fleeting glimpse of the intense life they might never live. To see a well-matched pair of crack steamboats tearing past, foam flying, flames spurting from the tops of blistered stacks, crews and passengers yelling — the man or woman or child of the backwoods who had seen this had a story to tell to grandchildren.2

The people of New Orleans, of course, where the race would start, were especially fascinated, even obsessed. The Picayune declared, “The whole town is given up to the excitement occasioned by the great race.... Enormous sums of money have been staked here on the result, not only in sporting circles but among those who rarely make a wager. Even the ladies have caught the infection, and gloves and bon bons, without limit, have been bet between them.”3 Among the people of New Orleans the Natchez was believed to be the favorite, it being considered a New Orleans boat and its owner being a year-round New Orleans resident.

In other cities along the Mississippi and Ohio interest in the race was almost equally high as in New Orleans. The New York Times reported from Memphis that “the excitement over the race between the R.E. Lee and the Natchez is intense. The betting is heavy, with the odds in favor of the Lee.” In St. Louis, it reported, “The excitement over the steam-boat race is very great here this evening, and large amounts of money are staked....” And in Cincinnati: “The race between the steamers Natchez and R.E. Lee, on the Mississippi River, has created more of a sensation here today than anything of the kind that ever occurred. There has been a great deal of betting. Between $100,000 and $200,000 have doubtless been staked.”4

There is no way of knowing how enormous was the total sum bet on the race, but it easily rose into the millions. Professional gamblers were having a field day. In New Orleans before the race began, they were giving odds on the Robert E. Lee. Seventy-five-dollars bet on the Natchez would return one hundred dollars if it beat the Lee.

More than bets were at stake, though. Winning a head-to-head race, and thereby establishing itself as the fastest steamboat on the river, would be a public relations and marketing windfall, potentially bringing new freight and passenger business to the winner, and increased profits along with it. Losing the race, particularly if by a considerable time, would be a humbling if not humiliating experience for both the boat and its crew, and possibly a costly one in lost future revenue.

Some of the backers of the race, influentials who had helped persuade the Robert E. Lee’s reluctant owner and captain, John W. Cannon, to agree to the contest, had still more in mind. The steamboat business was in a state of

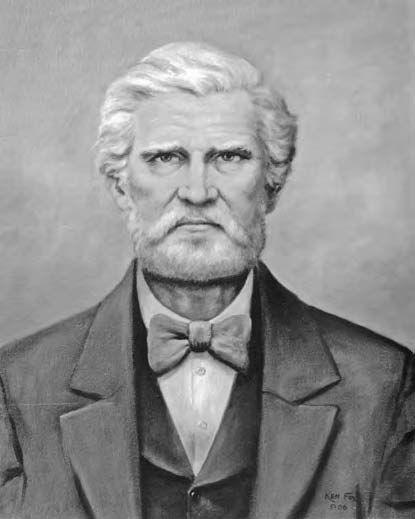

Thomas P. Leathers, owner and captain of the Natchez. Gruff, quick-tempered and physically imposing, Leathers had an intimidating presence and was determined to drive the Robert E. Lee off the Mississippi River (National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium, Captain William D. Bowell Sr. River Library).

decline and had been since the Civil War. The cause was railroads, which over their ever-expanding network of lines could carry passengers and freight faster, cheaper and to and from more destinations than could steamboats. Some steamboat owners who could remember the golden years of the 1840s and 50s thought there was a way to bring back the good times, if only shippers and passengers could have their attention diverted from trains back to the elegant floating palaces that steamboats had been before the war. A race between two of the western rivers’ best and fastest steamers — a gigantic publicity stunt — just might help the steamboat business gain new friends and regain old ones that had been lost to the railroads.

The most critical element of the race, however,

was the heated rivalry between the boats’ owner-captains — tall,

powerfully built, craggy-faced, fiftyfour-year-old Thomas P.

Leathers of the Natchez and intense,

husky, soft-spoken, fifty-year-old John W. Cannon of the

Robert E. Lee. Both men were Kentucky

natives, Leathers having been born in Kenton County, near

Covington, Kentucky, and Cannon near Hawesville in Hancock County,

on the Ohio River. Both had long experience with

steamboats.

At age twenty Leathers

had signed on as mate on a Yazoo River steamer, the Sunflower, captained by his brother John. In 1840, when he was twenty-four, he and his brother built a steamboat of their own, the Princess, which they operated on the Yazoo and later on the Mississippi, running between New Orleans, Natchez and Vicksburg. The brothers soon built two other steamers, Princess No. 2 and Princess No. 3, and prospered with them on the Mississippi. In 1845 Leathers built the first of a series of steamers that he named Natchez, each larger and faster than the previous one.

The third Natchez, large enough to carry four thousand bales of cotton, met with tragedy when a wharf fire engulfed it and destroyed it, taking the life of Leathers’s brother James, who was asleep in his stateroom. The fifth Natchez, capable of carrying five thousand bales of cotton, was the boat that transported Jefferson Davis to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was sworn in as the Confederacy’s president in 1861. It was operated by Leathers until it was pressed into service by the Confederates, first as a troop carrier and then as a cotton-clad gunboat on the Yazoo River, its works shielded by a wall of cotton bales. On March 23, 1863, twenty-five miles above Yazoo City, Mississippi, it was set ablaze and destroyed by its crew to prevent its capture by Union forces.

Following the fall of New Orleans in 1862, Leathers temporarily gave up the steamboat business. After the war, he returned to the river and in 1869 launched from its Cincinnati shipyard a brand-new Natchez, the sixth, of which he was immensely, even overbearingly, proud. He was confident — and boastful — that it could beat anything on the Mississippi.

When in his twenties, he had made his home in Natchez and there he had met Julia Bell, the daughter of a steamboatman, and he married her in 1844, when he was twenty-eight. Julia became a victim of yellow fever, and Leathers had then married Charlotte Celeste Claiborne of New Orleans, member of a prominent Louisiana family that included a former governor, William C.C. Claiborne. Leathers moved from Natchez and made his home in New Orleans, where he and Charlotte began raising a family and where he spent the Civil War years.

Gruff, hard-faced, quick-tempered and physically imposing, Leathers could be intimidating to his workers and to others. Once a steamboat mate, he never got over the use of the profanity-filled language that mates routinely used to drive their crews. Through his years as owner and captain, his mate’s vocabulary never left him, and along the river he became notorious for it.

Somewhere during his career Leathers picked up the nickname of “Ol’ Push,” which according to one account was a shortened form of the name of the heroic, nineteenth-century Natchez Indian chief Pushmataha, whom Leathers and his crew sort of adopted as the symbol and mascot of the Natchez, which they liked to call “the big Injun.” The nickname, however, could just as easily have been inspired by Leathers’s pushy personality. With his fast new Natchez he developed the irksome habit of letting other steamers shove off from the New Orleans wharves ahead of him, then while his excited and cheering passengers watched along the rails, he would make a grand show of speeding up and overtaking whatever lesser vessel had moved out into the river before him.

Leathers pulled that stunt once on John Cannon’s good friend John Tobin, when Tobin was master of the steamer Ed Richardson. Tobin never forgot the incident. He got his chance for revenge when he became captain of the third J.M. White, a big, new boat that had never been tested in a race. On a day that Tobin had been waiting for, the Natchez and the J.M. White were together at the New Orleans waterfront and backed off from the wharf about the same time. The speedy Natchez quickly moved out ahead and gained a lead while an accident aboard the J.M. White forced it to slow down so that repairs could be made. Once the repairs were completed, Tobin ordered the steam up, and the J.M. White, its powerful wheels churning against the current of the muddy Mississippi, glided abreast of the Natchez, then overtook it. Leathers, seeing he was beaten, pretended he needed to make a stop to unload freight and thus had to drop out of the contest. The freight that he unloaded was an empty barrel, which he reportedly kept aboard the Natchez to be used for just such embarrassing occasions.

Leathers’s attitude toward his steamboat business, which he managed with meticulous care, and his position in life were revealed in a story told about him by one of his fellow captains, Billy Jones of Vicksburg. Leathers, Jones claimed, would often refuse to accept the freight for a shipper or a consignee he didn’t like, and the firm of Lamkin and Eggleston, a wholesale grocery company in Vicksburg, was one of the shippers he didn’t like. When he declined to accept their freight, the firm sued him in circuit court and won a judgment against him. The judgment was upheld in the state supreme court, and Leathers had to pay the firm $2,500 in damages, which infuriated him. “What’s the use of being a steamboat captain,” he fumed in frustration, “if you can’t tell people to go to hell?”5

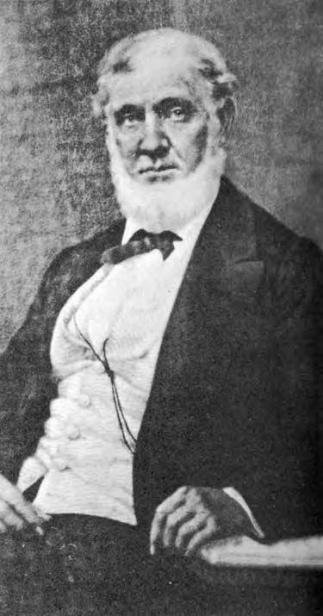

John Cannon, in personality, attitude and some other ways, was completely unlike Tom Leathers. Placid-faced, calm, quiet, he was a careful and far-sighted businessman who seemed more interested in the safety of his boat and passengers than in a showy display or establishing grounds for boasting. But like Leathers, he was a Kentucky farm boy who determined he would make something of himself. As a youngster he paid for his education with money earned by splitting rails. He began his life on the Mississippi aboard a flatboat and deciding the river was where he would pursue his fortune, he became a deckhand on a Red River boat and later a cub pilot on a Ouachita River steamer, the Diana, paying his pilot tutor out of the wages he earned working at a variety of jobs aboard the boat.

In 1840 he completed his training and became a licensed pilot. With money he saved from his pilot’s pay and with the help of several friends he built the steamer Louisiana, which came to a tragic end on November 15, 1849, when its boilers exploded at the Gravier Street wharf in New Orleans, taking eighty-six lives and shattering the two steamers docked on either side of the Louisiana. That experience likely affected his way of thinking about endangering other boats of his. Recovering from that disaster, Cannon went on to build or buy a dozen or more steamers, including the S.W. Downs, Bella Donna, W. W. Farmer, General Quitman, Vicksburg, J.W. Cannon, Ed Richardson and the Robert E. Lee.

The Robert E. Lee was built for Cannon in New Albany, Indiana, in 1866, the year after the end of the Civil War, and it was designed to be the most luxurious and fastest boat on the western rivers. When it came time to paint its name on the boat, an explosive problem arose. The display of the name of the South’s most famous general inflamed many of the people in New Albany and elsewhere, and Cannon had to have the unfinished boat towed across the Ohio River to the Kentucky side to prevent its being burned by enraged Indiana citizens, whose feelings were expressed in an editorial published in the Rising Sun, Indiana, newspaper, the Record, shortly before the race : “The people hereabouts who are interested in the race are friendly to the Natchez for many reasons. A steamer named for any accursed rebel General should scarcely be allowed to float, much less have the honor of making the best time....”

John W. Cannon, owner and captain of the Robert E. Lee. Cannon was goaded into racing the Lee against the Natchez by Tom Leathers, his business rival and personal adversary, with whom he had tangled in a fistfight in a New Orleans saloon.

The Robert E. Lee docked beside the Great Republic. The Lee was built for John Cannon in New Albany, Indiana, in 1866, the year after the Civil War ended. When its name was painted on its wheel housing, the boat had to be towed to the Kentucky side of the Ohio River to prevent its being burned by irate Northerners who objected to its being named for the Confederacy ’s most famous general (Library of Congress).

Actually, Cannon was believed to have been sympathetic to the Union, though after nearly a lifetime in the steamboat business, he, like Leathers, had many friends and business associates in both the North and South. Cannon was reported to be a friend of Union general Grant, and some suspected that he named his boat after the Confederate general to win approval in the South, where most of his customers were, and to compensate for his known Northern sympathies. Leathers, who refused to fly a U.S. flag on the Natchez even though the war had ended and who effected a sort of uniform of Confederate gray while captaining his boat, had at one time been arrested for suspected Union sympathies during the war, only to be pardoned by his friend Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president and former United States senator from Mississippi.

Cannon had managed to make a small fortune out of the war. He took his steamer General Quitman up the Red River and kept it hidden until Union forces had taken complete control over the Mississippi, then came steaming down from Shreveport to the Mississippi and up to St. Louis with a boatload of cotton that he had bought at depressed prices from planters unable to sell it on the usual markets. He then sold it for several times the price he had paid, netting a profit estimated at $250,000. With that bankroll, Cannon had little trouble paying the $230,000 that the Robert E. Lee cost him,6 or being able to afford two homes, one in New Orleans and the other in Frankfort, Kentucky, where he and his wife spent their summers.

The completed Robert E. Lee arrived in New Orleans on its maiden voyage in October 1866 and quickly proved itself as a fast steamer, setting new speed records and winning over flocks of new customers — while at the same time raising the ire and jealousy of Tom Leathers, who for a short time after the war had worked for Cannon as captain of the General Quitman. Cannon was said to have taken pleasure in having his rival work for him. The relationship between the two men remained a stormy one, though, and Leathers had left the General Quitman to command another steamer, the Belle Lee, in 1868.

In November 1868 their hostility toward each other broke out in a quarrel in a New Orleans saloon, while both apparently were under the influence, and a fistfight resulted. “Very little claret was drawn,” a waggish reporter commented while declaring that “Capt. Cannon had the best of the fight.”7 After that scuffle, they refused to speak to each other or even to exchange whistle salutes as their boats passed each other on the river, which was the custom among steamboatmen.

Reserved though he was, Cannon was not one to back away from a fight. In 1858, when he was master of the Vicksburg, he fired a pilot named Allen Pell and when Pell demanded to know the reason, Cannon, apparently in no uncertain terms, told him. The blunt answer drew an angry threat from Pell, and Cannon, thick-bodied and strong-armed, drove a heavy fist into Pell’s face in reaction, staggering him. Pell then pulled a knife from the sleeve of his coat, and Cannon, undaunted, grappled with Pell for the knife and was stabbed just above the groin. Cannon recovered and although his dealings with Pell were forever ended, Cannon had no qualms about hiring one of Pell’s relatives, James Pell, as one of his pilots aboard the Robert E. Lee.

In 1869, determined to best Cannon and boasting that he would drive the Robert E. Lee off the river, Leathers ordered a shipyard in Cincinnati to build him a boat, a new Natchez, that would outrace Cannon’s speedy, elegant Robert E. Lee. Leathers had come out of the war not nearly so well off

The Natchez, the sixth steamer to bear that name. It was built for Tom Leathers in Cincinnati in 1869 at a cost of $200,000 and was designed, by Leathers’ orders, to outrun the swift Robert E. Lee (National Mississippi River Museum and Aquarium, Captain William D. Bowell Sr. River Library).

as Cannon, having lost his boat during the conflict. He found financial backers, however, the chief of whom was Cincinnati businessman Charles Kilgour. The new Natchez, completed at a cost of some $200,000, began its first voyage down the Ohio and into the Mississippi on October 3, 1869. In June 1870 he was said to still owe $90,000 on the boat.

Cannon had repeatedly declined challenges to pit his boat against the Natchez. For a while, ever since the Lee had first been put into service, Cannon had run it between New Orleans and Vicksburg, the same run that the Natchez made. The Lee would leave New Orleans every week on Tuesday and the Natchez on Saturday. Fans of the two boats developed a sense of rivalry between them, each group sure of the superiority of their favorite and urging the two captains to race them and settle the question of which was faster. As if to dampen the enthusiasm for a race, Cannon altered the Robert E. Lee’s run in the spring of 1870. Its new schedule had it run between New Orleans and Louisville, leaving New Orleans every other Thursday. Leathers also dropped out of the New Orleans–Vicksburg trade that spring and he began running the Natchez between New Orleans and St. Louis, leaving New Orleans on Saturdays.

Calls for a race increased despite the change in schedules. Leathers was all for it. Throwing down his gauntlet, Ol’ Push announced that the Natchez, instead of leaving New Orleans on Saturday as usual, would leave on the same day, at the same time, that the Robert E. Lee left, forcing Cannon to run the Lee against him. Cannon still resisted, but on his return trip from Louisville in late June his shippers along the Ohio River repeatedly urged him to race. At last he gave in to the pressures coming from customers, from newspapers in the river towns from New Orleans to Louisville, from planters and merchants and other businessmen, from gambling interests — and from Leathers himself. Still, after he had agreed to the contest, he denied reports that he would engage in the race and had a notice to that effect published in successive editions of the Picayune, including the edition published on the morning of the day the race was to begin:

A CARD

Reports having been circulated that steamer R.E. LEE, leaving for

Louisville on the 30th June, is going out for a race, such reports

are not true, and the travelling community are assured that every

attention will be given to the safety and

The running and management of the Lee will in no manner be affected by the departure of other boats.

John W. Cannon, Master Leathers, likewise apparently fearing repercussions from some passengers and shippers, also had a denial published in the Picayune:

A CARD TO THE PUBLIC

Being satisfied that the steamer NATCHEZ has a reputation of being

fast, I take this method of informing the public that the reports

of the Natchez leaving

All passengers and shippers can rest assured that the Natchez will not race with any boat that will leave here on the same day with her. All business intrusted to my care, either in freight or passengers, will have the best attention.

T.P. Leathers,Master, Steamer Natchez

The Robert E. Lee arrived back in New Orleans from Louisville in the evening of Tuesday, June 28, and Cannon, having by then agreed to the race, having begun elaborate preparations for it and having become determined that his hated rival would not beat him, immediately ordered his magnificent Lee stripped of every possible impediment to speed. To reduce wind resistance, the window sash was removed from the front and back of the pilothouse, and the front double doors and the big aft windows of the main cabin were likewise removed. The decks aft of the paddle wheels had every other plank taken up to allow the spray from the wheels to quickly fall through the decks. The steam-escape pipes, the freight-lifting derricks, the spare anchors and extra mooring chains, everything that could be spared on the main deck and in the hold was taken ashore, along with virtually everything else that was portable, including most of the staterooms’ furniture and decorative accessories, and all freight had been refused. Left in place, however, was the large, handsome portrait of the boat’s namesake, General Lee.

The passenger list had been kept as short as possible. Captain Cannon announced to those passengers who already held tickets that plans had changed and the Lee was headed for St. Louis, not Louisville, and there would be no stops on the way. Passengers who had bought passage to Louisville and other destinations on the Ohio would be transferred to another steamer at Cairo, Illinois.

Even so, Cannon would have to accommodate some seventy passengers, including friends and some fellow captains, business associates and VIPs, all of them presumably eager to be participants in the history-making race. Two who perhaps were not so eager were the twenty-six-year-old carpetbagger governor of Louisiana, Henry Clay Warmoth, and his close friend and political ally, Doctor A.W. Smyth, chief surgeon at Charity Hospital in New Orleans. Smyth was also a close friend of John Cannon, and the two men — Smyth and Warmoth — had just arrived at the New Orleans riverfront on a steamer from Baton Rouge, where Warmoth had presented diplomas to graduates at Louisiana State University’s commencement exercises. What the two men encountered when they reached the wharf was the largest crowd the governor had ever seen in New Orleans. On the spur of the moment, Smyth had suggested they board the Robert E. Lee to greet Captain Cannon and wish him well. Delighted to have them aboard, Cannon insisted they stay for the ride. “Captain Cannon pressed us to go with him,” Warmoth wrote later, the event evidently a memorable one, “and, as we were carried away by the excitement and enthusiasm, we accepted the invitation.”8

Leathers, supremely confident of the Natchez’s prowess, had made no such preparations. The only concession he had made was the removal of the boat’s landing stage that swung from a derrick and which he acknowledged could catch the wind and slow the vessel somewhat. He had booked ninety passengers aboard the Natchez, with destinations requiring stops at Natchez, Vicksburg, Greenville, Memphis and Cairo. Others intending to board the boat would be waiting for it along the levee upriver from New Orleans. Leathers had also taken on a load of freight, evidently considering this run to St. Louis to be business as usual, only made at a greater speed than his rival who, he apparently believed, would also make a more or less normal trip.

The Natchez’s freight and passenger load would add considerable weight to the vessel, but despite it, Leathers’s boat would draw but six and a half feet of water, a foot less than the stripped and lightened Robert E. Lee. The difference in draft could be important in the race, and not only because the shallower-draft vessel would meet less resistance in the water. The Mississippi was reported to be falling, increasing the danger of a deep-draft boat’s running aground on the river bottom.

Other than their draft and a difference in their length and freight capacity, the two steamers, both side-wheelers, were about equal in size and equipment. The Robert E. Lee was 285 feet in length and forty-six feet in the beam; the Natchez was 303 feet long and forty-six feet in the beam. The height of the Robert E. Lee to its pilothouse was thirty and a half feet; the height of the Natchez was thirty-three feet. The Robert E. Lee’s paddle wheels were thirtyeight feet in diameter and seventeen feet wide. The Natchez’s paddle wheels were forty-two feet in diameter and eleven feet wide. Each boat had eight boilers, the Natchez’s being slightly larger (thirty-three feet long ) than the Robert E. Lee’s (twenty-eight feet) and capable of generating higher pressure (160 pounds) than the Robert E. Lee’s boilers (110 pounds). The engines were also similar. The Robert E. Lee’s cylinders were forty inches in diameter with a ten-foot stroke; the Natchez’s cylinders were thirty-six inches in diameter with a ten-foot stroke.9

To make sure, as sure as could be made, that the Lee was complying — and would continue to do so — with steamboat safety regulations, a U.S. steamboat inspector, a man named Whitmore, came aboard the vessel and examined the safety valves on each of the eight boilers. On each valve that could be locked, after locking it, he placed the government’s lead seal. Engineers would not then be tempted to manipulate the safety valves to increase steam pressure.

At fifteen minutes to five P.M., a quarter hour before the announced departure time for both boats, Captain Cannon gave three tugs on the Robert E. Lee’s ship’s bell to signal it was time for visitors to hurry ashore and for passengers to find their staterooms or a place at the rails. Captain Leathers immediately followed with three clangs on the Natchez’s bell. The last of the visitors having hustled ashore, the Lee’s mate shouted the order for the landing stage to be hauled in. As thick, black smoke erupted from the Robert E. Lee’s soaring chimneys, its bell sounded once more, an axe blade fell and severed the bowline that bound the vessel to the wharf, and the axe wielder suddenly raced for the end of the landing stage, grabbed it and held on as it came sliding onto the main deck.

Instantly then, minutes short of five o’clock, the big, grand vessel, its white woodwork gleaming in the afternoon sun, moved stern first into the streaming current of the Mississippi River, its giant paddle wheels churning a froth in the muddy flow.

The slightly early start had been carefully arranged by Cannon. He had gathered his officers together at four o’clock and given them instructions which, according to one of the assistant engineers, John Wiest, went as follows: “I want everybody aboard at five o’clock. The pilot in his house, but not in sight, the engineers at the throttle valves, the mate to have only one stage out and that at a balance so that the weight of one man on the boat end will lift it clear of the wharf. There will be a single line out, fast to a ring bolt, with a man stationed there, axe in hand, to cut and run for the end of the stage the moment he hears a single tap of the bell, and come aboard on the run or get left.”10

Knowing Leathers’s reputation for making sudden fast starts against competitors, Cannon had now out-fast-started him. The Lee had been docked just below the Natchez, and as it backed out from the wharf and made a crescent-shaped turn to head its bow upriver, the Natchez was forced to wait for Cannon to straighten out the Lee, lest the Natchez back across the Lee’s bow, or possibly into it. Once headed upstream, the Robert E. Lee fired its signal cannon as it passed St. Mary’s Market, just above Canal Street, the official starting point for timing all steamboat voyages from New Orleans. The time was a minute and forty-five seconds before five o’clock.11

As soon as the Lee had moved out of its way, the Natchez, distinguishable from a distance by its bright-red chimneys, backed away from the wharf, straightened out and with a surge of power steamed up to St. Mary’s Market, firing its signal cannon as it passed, the gun’s deep boom resounding over the noise of the yelling crowds on both sides of the river. The time then was two minutes after five o’clock.12

The race was on. Twelve hundred miles of river lay ahead.