The Pioneers

By the time he reached his fifties, Robert R. Livingston had assembled an impressive resume. He was a member of the five-man committee named to draft the Declaration of Independence (the four other members being John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Thomas Jefferson, who headed the committee). He was elected to the New York Congress in 1776 as a representative from Dutchess County and he served on the committee that wrote a constitution for the new state of New York. The New York Congress appointed him chancellor of the state, to preside over the state’s Chancery Court, and on April 30, 1789, as chancellor of New York, he administered the oath of office to George Washington when Washington was inaugurated as the new nation’s first president. In 1801 Livingston was appointed by President Thomas Jefferson to be the United States minister to France, the position from which he negotiated the Louisiana Purchase.

Widely considered both brilliant and learned, Livingston was elected the first president of the New York Society for the Promotion of Agriculture, Arts and Manufactures following its organization in 1791. He liked to think of himself as a practical scientist and he devoted two hundred acres of his vast estate on the east side of the Hudson River, Clermont, to agricultural experiments, which included using gypsum in the cultivation of corn, buckwheat and clover. He also conducted experiments to improve the breeds of his cattle and sheep.

In 1797 Livingston’s active mind lighted on the notion that he could build–or, rather, have built — a boat that would be powered by a steam engine. It wasn’t a new idea, Leonardo da Vinci having been possibly the first to imagine one and an obscure inventor named David Ramsay having received a patent for one in 1618 and another in 1630.1 Nothing came of those ideas, though, except their survival as possibilities in the inventive minds of persons who wished to find a way, as it was put in one patent application, of “making of Shipps to saile without the assistance of Wynde or Tyde.”2

49Another early steamboat was proposed by an English physician, John Allen, who described and patented it in 1729. Another was devised in 1736 by an English clock repairman named Hulls, whose creation, it was said, looked more like a clock than a boat. In 1760 a Swiss named Genevois came up with an idea for a boat that would be propelled by a watchlike works that would be wound by the force of steam. Throughout the remainder of the eighteenth century a succession of inventors — or men who hoped to become inventors — proposed a variety of steamboat schemes, most of them coming to nought.

The existence then of workable steam engines was keeping the steamboat dream alive. The Newcomen engine, named for its inventor, English blacksmith Thomas Newcomen, had been developed in the early 1700s, with a boiler positioned directly below a cylinder that contained one large piston. Steam entered the cylinder from the boiler and drove the piston upward, and when the piston reached the top of the cylinder, water was sprayed into the cylinder to dissipate the steam and create a vacuum, causing atmospheric pressure to draw the piston down to the bottom of the cylinder again, and the cycle was then repeated, the piston’s action providing continuous movement that could be applied to a number of uses, especially including pumping water out of mines. The steamboat devised and patented by the clock repairman Hulls in 1736 used a Newcomen engine to drive a paddle wheel. There is no record, however, of the boat’s having been built.

In 1783 a boat powered by a two-cylinder Newcomen engine and built by a French nobleman, Claude-François-Dorothée Jouffroy d’Abbans, actually proved workable in a short run on the River Saone at Lyons, France. It thus became the first boat to go against the current under its own power, unaided by wind or wave or the muscle of man or beast. For fifteen minutes, billowing smoke and sparks from the fire beneath its boiler, the vessel moved upriver at a speed that was as fast as a man could walk, cheered on by crowds gathered along the riverbanks. Then the boat’s bottom planks, taking a terrific beating from the pounding of the pistons, broke loose, opening the hull to a torrent of river water. What was more, the boiler’s seams burst, sending a cloud of steam into the air and killing the engine. But despite it all, Jouffroy managed to guide the stricken vessel to the river bank, where he leaped safely to shore, satisfied that he had achieved success for his invention. The French government, however, to which he was looking for additional financing to try again, refused to accept his account of his boat’s trial run, and when France exploded in revolution in 1789, Jouffroy fled the country, his experiments ended.

In 1769 a Scottish instrument maker and inventor, James Watt (for whom the unit of power, the watt, was named), patented a steam engine that made a significant technological advancement over the Newcomen engine. Watt decided that Newcomen’s engine would be much more efficient if the cylinder could be kept hot, instead of being cooled by the water sprayed into it to dissipate the steam, a process that required time to reheat the cylinder so that a new puff of steam would not immediately condense upon entering the cylinder. And so Watt devised a condenser, a container separate from the cylinder but connected to it by a valve that drew the steam out of the cylinder to provide the vacuum that caused the downward stroke of the piston. He later improved that engine by closing the top of the cylinder and introducing steam into it at both ends to create a reciprocating action that allowed the engine to generate power on both the upward and downward movement of the piston. That two-stroke design made for a more efficient, more cheaply run and much more smoothly operating engine. Its superiority soon made the Watt engine the standard of steam-engine design, even as its inventor continued to improve it and adapt it to a variety of uses.

John Stevens, a New Jersey land developer and inventor who was also Robert Livingston’s brother-in-law, had become deeply interested in the idea of a steamboat. Stevens knew about the steamboat-building efforts of John Fitch, the first man in America to build workable, though faulty, steamboats, which Fitch had been doing since 1785 with limited success. Stevens also knew about the experiments of James Rumsey, another American trying to build a workable steamboat. Stevens shared their passion and their handicap — the lack of sufficient funds to develop a dependable, commercially successful steam-powered boat. Stevens saw his wealthy brother-in-law as just the financial angel he needed to make his dream come true. He talked Livingston into bankrolling the construction of a steamboat in partnership with him.

Once committed to the project, Livingston quickly became an ardent student of steam power, reading every book he could find on the subject. Even so, his knowledge of engineering did not reach the level of Stevens’s, and his haughtiness prevented him from accepting some of Stevens’s suggestions for the construction of a test boat. In late 1797 Livingston entered a partnership with Stevens and machinist Nicholas J. Roosevelt, who operated a foundry on the Passaic River in what is now Belleville, New Jersey. Roosevelt was the man Livingston and Stevens needed to build not only the boat but the steam engine, the British government having prohibited the export of Watt engines built in Britain, forcing the Americans to build their own.

The boat design that Livingston gave Roosevelt called for a horizontal wheel mounted below the keel to provide propulsion, despite Roosevelt’s objection that the horizontal wheel would be inefficient. Vertical paddle wheels mounted on the sides of the hull, Roosevelt argued, would be much better. Livingston replied that his design was based on “perfectly new principles” and as the man who was paying the bills, he demanded that Roosevelt follow the plan.

Details of the venture were finally worked out between the three men — Livingston, Stevens and Roosevelt — and construction of the boat began in April 1798. Livingston participated from a distance, frequently issuing instructions to Roosevelt by mail, repeatedly making changes, but visiting the foundry only rarely while the work went on.

Finally, in August 1798, the building of the boat and the engine was finished and the engine was installed. It was time for a trial run. On the appointed day, however, the boat proved unable to move. Roosevelt blamed Livingston’s horizontal wheel while Livingston blamed Roosevelt’s steam engine. It was back to the drawing board. In October 1798, with adjustments having been made, but the horizontal wheel still in place, a new test run was scheduled. This time the boat managed to move upriver for a short distance at a rate estimated by Roosevelt as “three miles [an hour] in still water” before its heavily pounding engine shook apart both the boat and its machinery.

Livingston prepared to try again, making more changes to his design, more innovations. He tried an engine that used mercury instead of steam in its cylinder, but it, like all the other new ideas he came up with, failed to work. At last he realized he was no engineer and in February 1800 he teamed up again with Stevens in a new agreement that stated they would build a new boat and share the cost of it. With some reluctance, they again included Roosevelt in the arrangement, allowing him to contribute his foundry’s labor in lieu of cash.

Livingston’s attention, however, was then diverted to the task given him by President Jefferson in the fall of 1801, when he was sent to France to secure from Napoleon’s government the right of the United States to use New Orleans as a shipping base.

While in France on that assignment, Livingston

met an ambitious young American who captured his interest. He was

Robert Fulton, the son of an Irish immigrant, also named Robert

Fulton, who with his wife, Mary, had settled on a farm near

Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where young Robert was born on November

14, 1765, the fourth of the family’s five children. Fulton had

grown up in Lancaster, a manufacturing town with shops that

produced tools and farm implements as well as weapons that helped

General George Washington’s revolutionary army wage war against the

British. Fulton became acquainted with the sorts of things that

could be wrought from metal and the processes for doing

so.

Fulton also had a considerable talent for painting and drawing and

in 1785, at age twenty, he had set himself up in a studio in

Philadelphia to make a living as a painter of miniature portraits

suitable for enclosure in lockets and brooches. His portrait

business did well enough that in May 1786 he was able to buy

property for his mother and some of his siblings to live on in

western Pennsylvania. It also allowed him to move to grander

quarters, and he advertised in 1786 that he had “removed from the

northeast corner of Walnut and Second Streets to the west side of

Front Street, one door above Pine Street, Philadelphia.”

That new location placed him within a block of the Delaware River, where in the summer of 1786 John Fitch was experimenting with a forty-fivefoot boat powered by a steam engine with a three-inch cylinder and propelled by two sets of paddles, one mounted on each side of the craft. There is no evidence that Fulton witnessed, much less studied, Fitch’s contraption, but it drew a sizeable crowd to the riverbank, and Fulton, naturally curious, particularly about things mechanical, may well have been one of the most interested observers of Fitch’s experimental steamboat.

That same year, 1786, Fulton, troubled by a persistent cough, took time off to stay at a spa in West Virginia (then Virginia) in hopes of curing his ailment. While there he met some people to whom he showed his paintings and who were so taken with his work that they advised him to go to England and study under some of the prominent artists there, particularly Benjamin West,

Robert Fulton, inventor of the first successful steamboat. The son of an Irish immigrant, he was born near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where while growing up he became familiar with the making of machinery and metal devices (Library of Congress).

an American who had made a name for himself as a portrait painter in England. In the spring of 1787 Fulton, carrying about two hundred dollars and a letter of introduction to Benjamin West, sailed for England, arriving in late spring. Though West and his wife received him cordially, Fulton’s artwork failed to impress West enough for him to take Fulton on as a student, and eventually Fulton despaired of making a living as an artist.

His big, absorbing interest then became things nautical, particularly canals, canal locks and canal boats, all pertinent concerns of that day. He conceived ideas for improving them, but failed to find sufficient financial backing to put his ideas to work. In 1794 he corresponded with the company that James Watt and Matthew Boulton had formed, inquiring about buying from the company a steam engine that could be used to power a boat. He also came up with ideas for building a submarine, as well as designs for torpedoes and mines. In England he was unable to secure the financing he needed to develop his ideas and in June 1797 he boarded a ship at Dover and sailed across the Channel to Calais and from there traveled to Paris.

In Paris he obtained lodgings at a Left Bank pension that attracted wellto-do Americans and it was there that Fulton met Ruth Barlow, the charming Bohemian wife of the odd, affluent and socially prominent poet Joel Barlow, from Connecticut. Ruth was in Paris awaiting her husband’s return from Algiers, where as a representative of the United States government he was attempting to gain the release of American seamen held hostage by Barbary pirates. Ruth, a pretty, witty woman in her early forties, became attracted to the thirty-one-year-old Fulton, tall and handsome, with dark, curly hair and an engaging charm and vigor. Upon Barlow’s return from Algiers, Fulton charmed him as well, and the Barlows invited Fulton to move from the pension into an apartment with them, which he did, forming a fast friendship — and with Ruth, more than friendship, with Joel’s approval — that was to last many years. In late October 1800 Barlow bought a huge, handsome mansion for the three of them, at 50 Rue de Vaugirard, across from the Jardin du Luxembourg, in one of Paris’s poshest neighborhoods.

It is likely that Livingston met Fulton through the Barlows, probably at a dinner party given by them in early 1802 to show off their impressive new home, although there is no known record of the meeting. In any case, while in Paris, Livingston and Fulton became acquainted and in so doing discovered each other’s interest in steam-powered boats. At age fifty-five and impaired by increasing deafness, Livingston quickly developed an admiration for Fulton’s relative youth and vigor, his enthusiasm and his apparent knowledgeability about the mechanics of harnessing steam power to boats. Fulton, Livingston soon began to think, might be just the person he needed to help him create a steamboat that could navigate the Hudson between New York and Albany no matter the wind, weather or current.

Fulton of course saw in Livingston a Daddy Warbucks whose money could make Fulton’s dream of creating a great invention — one that would make him the fortune he sought — come happily true. Before long, the two men reached an agreement to cooperate in the building of an experimental steam-powered boat. They decided it would be best to buy an engine rather than build one, and Livingston, with his diplomatic connections, got the job of seeking permission from the British government to export — to the United States, since Britain and France were at war — one of the engines manufactured by the firm of Watt and his partner, Boulton. Livingston also assumed the burden of footing the bill for the boat’s construction. Fulton’s task was to come up with a workable propulsion system and hull design — the two major problems plaguing others who were trying, or had tried, to build a practicable steamboat.

Fulton’s latest propulsion idea at that time was to create what was very much like a bicycle chain, to which paddle boards would be attached and which would rotate in a long oval, propelling the boat as the paddle boards moved continuously through the water, drawn by the chain. To test the idea he ordered a three-foot-long model built, the propulsion chain for which would be actuated by clock springs. He planned to observe the working of the model, then design a full-size boat based on the proportions of the model. At the time, Fulton, a lover of the good life, was staying — with Ruth Barlow — in the fashionable mountain resort town of Plombières, where the model was to be sent to him and where he would test it in a section of a stream he had prepared for the model’s run. He and Livingston, still in Paris, kept in touch by mail.

The model arrived in Plombières in late May, and Fulton promptly put it to the test. On the basis of the test, he decided that the full-size boat should be ninety feet long and six feet in the beam. Ever quick with a sharp pencil, he calculated that the full-size craft could travel at a speed of eight miles an hour, carry fifty passengers and make the New York-to-Albany voyage in eighteen hours. He figured that the boat would burn a ton and a half of coal and that the cost of the coal plus the salaries of the crew would bring the expenses to no more than twelve dollars per trip, and assuming a capacity load of fifty passengers, the profit per trip would be $198. Days later he revised his figures and projected that he could make the boat two hundred feet in length and twelve feet in the beam, have it carry one hundred and twenty passengers and attain a speed of sixteen miles an hour, shortening the running time to Albany, he estimated, though unsure of the distance, to twelve hours.

He wrote to Livingston to inform him of the progress he had made in developing the proposed boat from his experiments with the model and with small deference to Livingston’s position as sole financier, he demanded a report on Livingston’s progress in his part of the project. “Having now finished my experiments,” Fulton wrote, “I will thank you to let me know how you proceed with yours.” Fulton now could clearly see grand possibilities, all of them owing, as he saw it, to his efforts, and he wrote again to Livingston, this time to propose an agreement that would have the two of them split the profits from the boat’s operation fifty-fifty. He gave Livingston his justification for such a deal. “The leading principle,” he wrote with candor, “...is that I estimate my time (for it is my attentions which must carry it all into effect, and my knowledge of the subject) as an equivalent to your money.”3

Livingston had some doubts about Fulton’s boat design, thinking the slender craft might prove unable to withstand the constant pounding of the engine’s piston, and he balked outright at Fulton’s fifty-fifty-split proposal, telling him that “the demand you make of half the profits” was “much too great a compensation for the labour and time it will cost you.”

Apparently worried that, as Livingston warned, he could not be issued a U.S. patent for his so-called endless-chain propulsion system because such a device was already in use, Fulton abandoned the endless chain and substituted vertical paddle wheels to propel the proposed boat. They of course were not a new idea either. Paddle wheels turned by oxen were used by the Romans to propel boats before the first century A.D., and warships propelled by paddle wheels turned by manpower were used by the Chinese in the seventh century A.D. Roosevelt, too, had proposed vertical paddle wheels. Nevertheless, Fulton felt he could patent his paddle wheel and establish exclusive rights to the device he would design. “Although the wheels are not a new application,” he reasoned, “yet if I combine them in such a way that a large proportion of the power of the engine acts to propel the boat in the same way as if the purchase [of the wheel] was upon the ground the combination will be better than anything that has been done up to the present and it is in fact a new discovery.”4

After some sparring over the details of a partnership arrangement between them, Livingston, evidently seeing Fulton as his best hope for realizing his steamboat dream, at last agreed to the fifty-fifty split on profits. He did so on the condition that Fulton also invest money in the enterprise. On October 10, 1802, the two men signed an agreement to form a company that would seek a U.S. patent for “a new Mechanical combination of a boat to navigate by the power of a Steam Engine” and that would run between New York and Albany at eight miles an hour in still water and carry at least sixty passengers, allowing two hundred pounds per passenger. Livingston and Fulton each subscribed to fifty shares in the company. Fulton would go to England and build a prototype of the same specifications, using an engine to be borrowed from Boulton and Watt.

While Livingston was anteing up the capital over the next couple of months, Fulton tried to persuade Boulton and Watt to let him borrow one of their engines. His request was firmly rejected, and in the spring of 1803 he went to French machinist Jacques Perier to ask him to build the engine. Fulton had worked with Perier four years earlier, in 1799, when his bright idea of the moment was a rope-making machine, an idea that failed a year later when he ran out of money and financial backers. Perier had also collaborated with Fulton on the construction of the submarine Fulton had conceived, another scheme that failed. Perier had not only visited the Boulton and Watt foundry and machine shop in Birmingham and observed its operations but had also acquired a Watt engine and installed it in a Paris waterworks. Now he agreed to build the engine that Fulton — and Livingston — needed for their experimental boat. Etienne Calla, the man who had built the three-foot model, would put together the boiler and some parts of the engine.

This time Fulton would use vertical paddle wheels for propulsion, one mounted on each side of the boat, instead of the rotating chain he had used on the model. As for the hull, he boned up on the studies made by others, including renowned French mathematician Charles Bossut and English researcher Charles Mahon, Earl Stanhope, to determine the most efficient shape, the one likely to effect the least resistance as the craft moved through the water. Fulton further had the advantage of having seen drawings of the steamboat model designed by a French inventor named Desblancs — which had been on exhibit at the Paris Conservatory of Arts and Trades and of which Joel Barlow had made a sketch that he had sent to Fulton at Plombières. Fulton might also have seen the plans for Claude Jouffroy’s boat, which were in Jacques Perier’s possession, and he knew about John Fitch’s experimental boats, plans for which Fitch had left in Paris. And of course he knew about the creations of Livingston, Stevens and Roosevelt, as well as about the attempts of others.

After much contemplation, Fulton, a painstakingly careful worker, finally decided on a flat-bottomed, keelless hull with a tapered bow and stern. The boat would be steered with a rudder and tiller. Its two paddle wheels would each have ten spokes with rectangular boards attached at their farthest ends to serve as paddles. The engine, held in place and supported by a special framework, would be positioned amidships, mounted on the boat’s bottom planks, which would be reinforced beneath the piston and the boiler. The engine and its components would take up about half of the space in the hold.

His intention, he said, was to employ the craft upon America’s long rivers, making of them thoroughfares of transportation where roads were nonexistent and where conditions were such as to make the hauling of boats by men or beasts laborious, hazardous and expensive or, in some places, impossible. He evidently had the Mississippi River in mind — not, as Livingston did, the Hudson.

By May of 1803 the hull, fifty-six and a half feet long and ten and a half feet in the beam and lying tied up in the Seine near Perier’s plant, was ready to receive Perier’s engine, which along with the boat’s other machinery was installed sometime that month. The craft, in public view, made quite a spectacle. One Paris journalist described it as having “two large wheels mounted on an axle, like a cart” and behind the wheels rose “a kind of large stove with a pipe.” The creation born in Fulton’s imaginative mind had at last become a reality, floating as a curiosity on the Seine, nearing completion and the crucial test voyage that would follow.

Then tragedy struck. Fulton was awakened one night to be told that the boat had been damaged and had sunk to the bottom of the river, possibly the work of saboteurs — Seine boatmen bent on destroying what they saw as a threat to their livelihood. Another possible cause, though, was that the heavy machinery had simply broken through a hull inadequate to support it. Fulton quickly roused himself and hurried to the riverfront, enlisting help to recover the machinery from the water. Working through the night and deep into the next day, Fulton and his helpers managed to raise the engine, boiler and condenser and salvage as much else as they could. The boat itself, however, was a ruin, and a new one would have to be built.

By the end of July the new hull was finished, built not with Livingston’s money but with funds Fulton raised on his own, probably from Joel Barlow. This time the boat was seventy-four and a half feet long and approximately eight feet in the beam, substantially slimmer than the one that had been destroyed. When all was in readiness, Fulton issued an invitation for a public demonstration of the boat’s operation, asking France’s prestigious and influential National Institute to send a delegation to witness the demonstration, which was to take place on Tuesday, August 9, 1803, at 6 P.M. The boat was scheduled to make a run in the Seine between the Barriere des Bons Hommes and the Chaillot waterworks, a distance of about a mile.

At the appointed time, a large crowd of curious onlookers gathered on the banks of the river to behold the spectacle to be put on by the strangelooking, fire-breathing, floating contraption that would attempt to navigate the Seine. The event was recorded in the Journal des Debats:

At six o’clock in the evening, helped by only three persons, he [Fulton] put the boat in motion with two other boats in tow behind it, and for an hour and a half he afforded the strange spectacle of a boat moved by wheels like a cart, these wheels being provided with paddles or flat plates, and being moved by a fire engine.

As we followed it along the quay, the speed against the current of the Seine seemed to be about that of a rapid pedestrian, that is about 2,400 toises (2.90 miles) an hour; while going down stream it was more rapid. It ascended and descended four times from Les Bons Hommes as far as the Chaillot engine; it was maneuvered with facility, turned to the right and left, came to anchor, started again, and passed by the swimming school.

One of the [towed] boats took to the quay a number of savants and representatives of the Institute, among whom were Citizens Bossut, Carnot, Prony, Perier, Volney, etc . Doubtless they will make a report that will give this discovery all the celebrity it deserves; for this mechanism applied to our rivers, the Seine, the Loire, and the Rhone, would bring the most advantageous consequences to our internal navigation. The tows of barges which now require four months to come from Nantes to Paris would arrive promptly in from ten to fifteen days. The author of this brilliant invention is M. Fulton, an American and a celebrated engineer.5

The two boats that Fulton’s craft had towed, in which Fulton had provided French government officials and other VIPs a ride to let them participate in the big, historic event, had no doubt slowed his steamboat and had partly accounted for its failure to reach the sixteen-mile-an-hour speed he had predicted. But Fulton was far from being discouraged by the boat’s performance. He would simply have to use a more powerful engine next time — and he would give up the idea of towing other craft.

There was a good reason for Fulton and Livingston to move promptly from their prototype, once it had passed its test, as it had, to the actual steampowered boat that would ply the Hudson on a regular schedule, as Livingston had long envisioned. Livingston had used his and his family’s powerful political influence to obtain from the New York State legislature the right to be sole operators of steamboats on the Hudson — a privilege Livingston and Fulton hoped to also gain on other American rivers. The Hudson monopoly had been first granted to Livingston in March 1798, its primary justification being to protect the Livingston boat from potential competition by imitators who would copy the designs of the craft in which Livingston had invested so much of his time and money.

The legislature granted Livingston a monopoly that would, under the terms specified by the legislation, last twenty years, but did so with conditions that the steamboat Livingston proposed must meet. It must : (1) have a capacity of not less than twenty tons; (2) attain a speed of not less than four miles an hour; and (3) be in operation within a year — that is, by March 1799. The boat that Nicholas Roosevelt had built for Livingston, and Stevens, during its test in October 1798, failed to meet the speed requirement and was eventually abandoned. Livingston managed to have the New York legislature extend its deadline — twice — and the latest deadline was April 1807. He must have a steamboat operating successfully by then in order to keep his monopoly rights.

It was not until April 1804 that Fulton made the move from Paris to pursue the construction of a boat that would meet the New York legislature’s conditions. He informed Livingston that he was leaving for England to oversee the manufacture of the Boulton and Watt steam engine that was intended to power a boat that would be built in the United States. He got Livingston to enlist fellow diplomat James Monroe’s help in obtaining from the British government the export license needed to ship the proposed engine to America. In so doing, Livingston emphasized to Monroe the importance of the engine to commerce on the Mississippi, over which, thanks in part to their efforts, the United States had so recently acquired complete control through the Louisiana Purchase.

Fulton left for London on April 29, 1804. He did not get to the United States till two and a half years later. Evidently unknown to Livingston, Fulton had been asked by British officials, through an American agent, to come to England to build and stage a demonstration of his submarine, or plunging boat, as it was called, and his mines, which were called torpedoes. Since hostilities between England and France had resumed and a French invasion of England had become a new possibility, the British war office had decided to give Fulton’s infernal machines a try in hopes they could be used to combat the menace of the expanding French fleet.

Fulton had leaped at that new chance for fortune and fame. The British government ended up paying him not exactly the fortune he sought but enough to make him richer than he had ever been. His weapons of war, though, failed the test of practicability, and the British government in 1806 at last abandoned its hope of using them to fight France.

Fulton did succeed in obtaining permission for Matthew Boulton (who had taken over the company following Watt’s retirement) to build him the needed machinery to his specifications, including the steam engine, the condenser and an air pump, all for the price of 548 pounds, or about $2,740. He also got a London firm to make him a two-ton copper boiler, for 477 pounds, about $2,385. Everything was completed by March 1805, whereupon Fulton was granted a permit to export the parts to America.

With all necessary business taken care of and with no further gains to be realized from his war weapons in England, Fulton finally made preparations to return to the United States. He bought passage aboard a ship and sailed from Falmouth in October 1806. After seven turbulent weeks at sea he arrived safely in New York on December 13, 1806. He had been gone twenty years and was now forty-one years old. With Livingston’s deadline of April 1807 just four short months away, Fulton wrote to Livingston shortly after his arrival to tell him that he was ready to move ahead with their steamboat. But then he went to Philadelphia to be with the Barlows, who were living there at the time, and from Philadelphia the three of them went to Washington City, as the nation’s capital was then called, and stayed a month, entertaining and being entertained and joining in the celebration that welcomed Meriwether Lewis back from his epic journey across the North American continent.

When he returned to Philadelphia, Fulton dawdled awhile longer, then at last went to New York to get started on the building of the boat. It was the middle of March 1807 when he reported that construction had started at the Charles Browne shipyard at Corlear’s Hook, on the East River in lower Manhattan. Not long after that, he took the steam engine and other machinery parts out of storage in the U.S. Customs warehouse, where they had been since November 1806. Near the end of March he reported, “I have now Ship Builders, Blacksmiths and Carpenters occupied at New York in building and executing the machinery of my Steam Boat.” He said the boat’s construction would take four more months to complete, well past the legislature’s deadline. Livingston responded by having the legislature extend the deadline once again, for another two years.

By the middle of July the hull was far enough along for the two paddle wheels to be mounted on its sides and for Fulton to plan a test for the boat at the end of July. The craft was one hundred and forty-six feet long, thirteen feet in the beam, flat-bottomed and straight-sided, but with a curved bow. Two masts, one fore and one aft, would allow the boat to be rigged with square sails that could be used if the engine failed. The cost of the boat’s construction had risen sharply, doubling to $10,000 the $5,000 that Fulton had originally estimated he and Livingston each would have to contribute.

The boat’s first test was held on Sunday, August 9, 1807, exactly four years since the trial run of Fulton’s experimental craft on the Seine. Following the new test, Fulton gave Livingston a brief written report : “I ran about one mile up the East River against a tide of about one mile an hour ... according to my best observations, I went 3 miles an hour.... Much has been proved by this experiment.” He told Livingston that he would overhaul the engine and make some adjustments to allow the vessel to make more speed. He predicted that it would achieve the required four miles an hour and said that he was planning to take it on its maiden voyage from New York to Albany on Monday, August 17, 1807.

Even while preparing for the voyage up the Hudson, though, Fulton was thinking ahead. “Whatever may be the fate of steamboats on the Hudson,” he told Livingston in the final sentences of his report, “everything is completely proved for the Mississippi.”6 About that same time, he gave an interview to a reporter for the American Citizen, who, further revealing Fulton’s ambitions, commented in print that Fulton’s “Ingenius Steamboat, invented with a view to the navigation of the Mississippi from New Orleans upward ... [would] certainly make an exceedingly valuable acquisition to the commerce of the Western States.”7

To make sure the boat would be ready for the August 17 run, Fulton put it through another trial on Sunday, August 16. He seemed to prefer Sundays for demonstrations, presumably because Sundays provided bigger crowds and he wanted to show off his creation to as many people as possible. He moved the boat, under steam, from the East River, around the Battery, at the lower tip of Manhattan, then steamed up a short distance on the North River, as the lower Hudson used to be called, and tied the boat up at a dock near Greenwich Village. With him on the short voyage were a number of Livingston’s friends and relatives, including United States senator Samuel Latham Mitchell, who when he was a member of the New York legislature had introduced the first bill to grant Livingston a steamboat monopoly on the Hudson.

Monday, August 17, dawned bright and warm, promising a hot summer day, and the tide tables said that high tide, reaching up the river from the lower and upper New York bays, would be at eight o’clock that morning and the tide would flood again just before two that afternoon. With a small crew and about forty passengers, mostly Livingston relatives and friends, aboard with him, and a throng of onlookers lining the docks and riverbank, many of them hooting and jeering the ungainly-looking craft, Fulton shouted orders to his captain, Davis Hunt, and his engineer, George Jackson, and at about one o’clock in the afternoon Fulton’s boat, as yet unnamed, cast off its lines and slipped away from the wharf, its grist-mill-looking wheels churning through the water, moving the boat against the current and the ebbing tide, its white-pine fuel sending up columns of smoke and fiery sparks from the craft’s tall stacks.

After a short distance, with all seeming to go well, the boat’s engine abruptly stopped, setting off a wave of anxiety that swept through the passengers. Fulton described the incident and the reactions to it :

The moment arrived in which the word was to be given for the boat to move. My friends were in groups on the deck. There was anxiety mixed with fear among them. They were silent, sad, and weary. I read in their looks nothing but

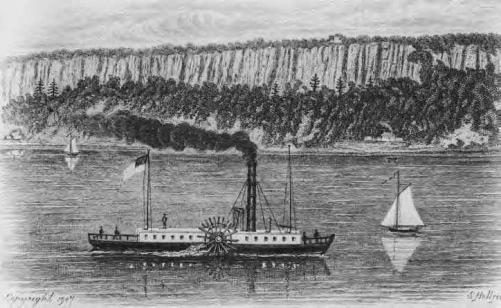

The North River Steam Boat, also known as the Clermont, the pioneering creation of Robert Fulton and his financial backer, Robert Livingston, steams up the Hudson River from Manhattan and after three days reaches Albany about 5 P.M. on August 19, 1807. “She is unquestionably the most pleasant boat I ever went in,” one of its passengers remarked. “In her the mind is free from suspense” (Library of Congress).

disaster, and almost repented of my efforts. The signal was given and the boat moved on a short distance and then stopped and became immovable. To the silence of the preceding moment now succeeded murmurs of discontent, and agitations, and whispers and shrugs. I could hear distinctly repeated —“I told you it was so; it is a foolish scheme; I wish we were well out of it.”

I elevated myself upon a platform and addressed the assembly. I stated that I knew not what was the matter, but if they would be quiet and indulge me for half an hour, I would either go on or abandon the voyage for that time. This short respite was conceded without objection. I went below and examined the machinery, and discovered that the cause was a slight maladjustment of some of the work. In a short time it was obviated. The boat was again put in motion. She continued to move on. All were still incredulous. None seemed willing to trust the evidence of their own senses. We left the fair city of New York.8

From that time on, the voyage — and the steamboat — proceeded flawlessly. Onward the craft chugged and splashed, and as night came on, the women retired to a cabin near the stern. On cots provided them they tried to sleep despite the constant pounding of the engine. The men, most of them, stayed up, keeping themselves occupied by singing, their voices carrying across the water in the night air. They passed through Haverstraw Bay, churned past the Highlands and on beyond West Point. At daybreak the light revealed the many curious onlookers along the riverside. About the middle of the morning of Tuesday, August 18, the boat came round the river’s bend at Kingston, and the passengers could then make out the Catskill Mountains in the hazy distance.

At last, at one o’clock that afternoon, they reached the dock at Livingston’s Clermont estate, the one scheduled stop on the trip to Albany. Its safe arrival signaled a huge success for the boat. It had made the one-hundred-and-tenmile voyage to Clermont in twenty-four hours, achieving an average speed of slightly better than four and a half miles an hour. Waiting at the dock was a jubilant Robert Livingston, happy to see and eager to welcome the pioneer voyagers and the novel craft that had brought them to him.

At a little past nine o’clock the next morning, Wednesday, August 19, having left most of his passengers at Clermont, Fulton steamed off again. This time, Livingston was aboard. The boat, which later would be named simply the North River Steam Boat, but would become popularly, although mistakenly, known as the Clermont, arrived at Albany about five P.M. after an uneventful forty-mile trip. The governor of New York and a host of astonished citizens were at the waterfront to offer an enthusiastic welcome to the participants of the history-making voyage.

One of the passengers, an Anglican clergyman, reporting on the experience, summed up the remarkable success of Fulton’s boat : “She is unquestionably the most pleasant boat I ever went in. In her the mind is free from suspense. Perpetual motion authorises you to calculate on a certain time to land; her works move with all the facility of a clock; and the noise when on board is not greater than that of a vessel sailing with a good breeze.”9

The next morning, Thursday, August 20, 1807, Fulton and his boat were ready to leave for the return trip to New York. This leg of the North River Steam Boat’s round trip, however, would not be a free ride. The boat overnight had become a commercial vessel. Fulton had a sign made and had it hung on the side of the boat. The sign announced that passage to New York was available to the public . The fare : seven dollars, meals included. Two courageous travelers bought tickets to become the North River’s first paying passengers.

America’s steamboat era had begun.