LEVEL TEN

Take the Fear Out of April 15

When I moved from Texas to Los Angeles to pursue a writing career, I saved up a decent sum of money, which I aptly called my “What If I Can’t Find a Job?” fund. The fund would get me through six months of rent, food, and other basic living expenses in the very likely case that I couldn’t find a job. By the time I did find a job, I had exactly $5,000 left in that fund. At that point, it became my emergency fund.

Life wasn’t bad. Sure, I could have (and should have) had more in that emergency fund. Sure, the job could have paid better. And yes, I could have had a better apartment. But for the most part, I was living the dream: working in a big city, collecting a paycheck every two weeks, and eating In-N-Out on the weekends (which is still not better than Whataburger, but I digress). For a while, my financial life was pretty good.

Then, on a Friday evening in April, I decided to do my taxes. Ever since I started working at sixteen, I loved tax season. It always meant I got a big, fat, unexpected refund in April. This time was different, though. As I navigated the tax software program, the little number in the top left side of the screen turned red, not green. Red was bad. Red meant I owed money. Worse, the number kept getting bigger and bigger. I thought there must be an error when I got to the last screen of the software and it told me I owed nearly $5,000.

“I’m doomed,” I actually said out loud. It was a phrase you only ever hear in cartoons and bad movies, but it seemed the perfect way to explain my current state of financial existence. Not only had I never before owed the IRS money on April 15, I could never imagine owing that much money to anyone at once. So what happened?

Turns out, I was technically on the books as a freelancer. Unlike any other job I had, that meant my employer didn’t withhold taxes for me throughout the year: that was supposed to be my responsibility, but I hadn’t been paying attention. In a single night, I completely obliterated the entirety of my savings. Worse, I now realized I needed to pay taxes every three months as a freelancer, but I was barely earning enough to pay rent. I had to both survive and pay taxes, and in my current state, it seemed I could only afford one or the other. I’d worked so hard to get to this place in my life, and, it turned out, I couldn’t afford to stay in that place. I smashed my face into my pillow, tried not to cry, and thought, This is it. I’m broke again.

Taxes can be scary when you don’t know what you’re doing (just ask Lionel Richie, Nicolas Cage, and the Osbournes—celebrities are just like us!). Especially with so many workers switching from full-time to freelance, it’s crucial to understand the basics of how your taxes work.

TAXES 101

Even if you rely on an employer to take care of your taxes for you, it’s in your favor to understand how the process works. Most people, for example, have no idea how they’re even taxed in the first place. You’ve probably heard about tax brackets, but did you know each portion of your income is taxed at a completely different percentage? There’s a difference between tax brackets, your marginal tax rate, and your effective tax rate.

How Tax Brackets Work

Our income tax system is a graduated one, meaning you pay more in taxes as your income increases. And that might not mean what you think it means.

The IRS divides taxable income into different ranges, better known as tax brackets. Each range is taxed at a certain percentage. Here were the brackets for 201746:

Tax Rate: 0%

Single Filers: 0–$9,325

Married Filing Jointly: $0–$18,650

Married Filing Separately: $0–$9,325

Head of Household: $0–$13,350

Tax Rate: 15%

Single Filers: $9,326–$37,950

Married Filing Jointly: $18,651–$75,900

Married Filing Separately: $9,326–$37,950

Head of Household: $13,351–$50,800

Tax Rate: 25%

Single Filers: $37,951–$91,900

Married Filing Jointly: $75,901–$153,100

Married Filing Separately: $37,951–$76,550

Head of Household: $50,801–$131,200

Tax Rate: 28%

Single Filers: $91,901–$191,650

Married Filing Jointly: $153,101–$233,350

Married Filing Separately: $76,551–$116,675

Head of Household: $131,201–$212,500

Tax Rate: 33%

Single Filers: $191,651–$416,700

Married Filing Jointly: $233,351–$416,700

Married Filing Separately: $116,676–$208,350

Head of Household: $212,501–$416,700

Tax Rate: 35%

Single Filers: $416,701–$418,400

Married Filing Jointly: $416,701–$470,700

Married Filing Separately: $208,351–$235,350

Head of Household: $416,701–$444,550

Tax Rate: 39.6%

Single Filers: $418,401 and above

Married Filing Jointly: $470,701 and above

Married Filing Separately: $235,351 and above

Head of Household: $444,551 and above

Upon first glance, you might think that if you’re single and you earn $80,000, that means your entire income is taxed at 25 percent. It’s a common belief, but it’s not how tax brackets work. Of course not. Nothing tax-related is that simple.

“The tax brackets in which the IRS adjusts earning ranges for inflation each year are what most folks think of as our tax rate,” says Kay Bell, a personal finance journalist and tax expert. “You could say you’re in the 25 percent tax bracket, and be correct. But that’s only half of the tax rate story,” Bell says.

Your marginal tax rate is the rate on the “last dollar of income earned.” Your marginal tax rate is 25 percent, which means only the portion of your income above $37,950 is taxed at 25 percent. Here’s how the rest of your income is taxed, assuming you’re a single filer:

Your first $9,325 is taxed at 10

percent.

Your first $9,325 is taxed at 10

percent.

Anything after that, up to $37,950,

is taxed at 15 percent.

Anything after that, up to $37,950,

is taxed at 15 percent.

The rest of your income—$42,050—is

taxed at 25 percent.

The rest of your income—$42,050—is

taxed at 25 percent.

Again, 25 percent is your marginal tax rate, but you can’t just multiply .25 by 80,000 to figure out how much you owe in taxes. That’s what your effective tax rate tells you.

“The percentage of your earnings that we actually eventually pay in taxes to the U.S. Treasury is your effective tax rate,” Bell explains. And that’s a smaller percentage.

“A person’s (or couple’s) effective tax rate is the average rate of tax on all dollars, not just the last one that bumped them into a higher tax bracket,” she says. “This difference comes thanks to the progressive nature of our tax system. And don’t forget that before figuring any tax bill, a filer gets to subtract the exemptions, credits, and deductions for which he or she qualifies. These also will lower taxable income and, in the case of credits, a taxpayer’s actual final tax-due amount, further reducing the filer’s effective tax rate.”

All in all, it can be very confusing to figure out how much you actually owe in taxes, especially considering deductions, credits, and exemptions, which we’ll get to soon. For now, all you really need to know is how your income is actually taxed.

Withholding

If you’re a standard employee (not a freelancer, independent contractor, gig worker, self-employed, etc.), your employer should withhold money from each paycheck. This is called—wait for it—withholding.

Your employer withholds this amount and pays the IRS on your behalf. Come April 15 (or earlier, if you’re not a tax procrastinator), the entire amount you’ve withheld throughout the tax year is applied to the amount due on your taxes. If you didn’t pay enough, you’ll owe the IRS some money. If you paid too much, you should get a refund.

Your company knows how much to withhold from your paycheck based on IRS Form W-4 (Employee’s Withholding Allowance Certificate). You should have filled out this form when you first started working at that employer, and the form itself comes with instructions to help you do that. We’ll get to how this works and how to change your W-4, if you need to, later.

Adjusted Gross Income vs. Taxable Income

To make matters even more confusing, there’s your income, taxable income, and adjusted gross income. Your income is fairly obvious: you sell paper and earn $40,000 a year. Donezo. This doesn’t, however, mean you’re taxed on the full $40,000.

Your adjusted gross income (AGI) is your gross income after certain tax break adjustments. Your AGI is important because it can impact how many other types of deductions you’re eligible for. Your taxable income is the amount of your income on which you’re taxed after exemptions and itemized deductions (aka more sweet tax breaks) have been subtracted from your adjusted gross income.

A BASIC GUIDE TO DOING YOUR TAXES

Once all your tax forms have been handed over and mailed to you, likely at the beginning of the year, you should be ready to do your taxes. Whether you’ve never done them before or you just want to make sure you’re doing them right, you’ll learn how the process works in this section.

Start by organizing all your tax paperwork—1099s, W-2s, and everything else. I put mine in three piles:

Income: Any 1099-MISC forms I’ve received from freelancing clients. (If you’re an employee, this pile would just include your W-2.)

Interest and investments: If you earned money on an investment account or savings account, you should get a 1099-DIV or -INT for this, respectively, and you’ll want to group these together in their own pile.

Deductions: Group all your deductions in a pile, too. This will include receipts for donations, your 1098-E for student loan interest or 1098 for mortgage interest. In other words, all the stuff you should be able to deduct.

Depending on how much paperwork you’re dealing with, filing can be tedious and time-consuming. That said, it basically boils down to a few simple steps: Report all your income; claim any deductions, exemptions, and credits to figure out your taxable income; and calculate how much you owe, based on this income.

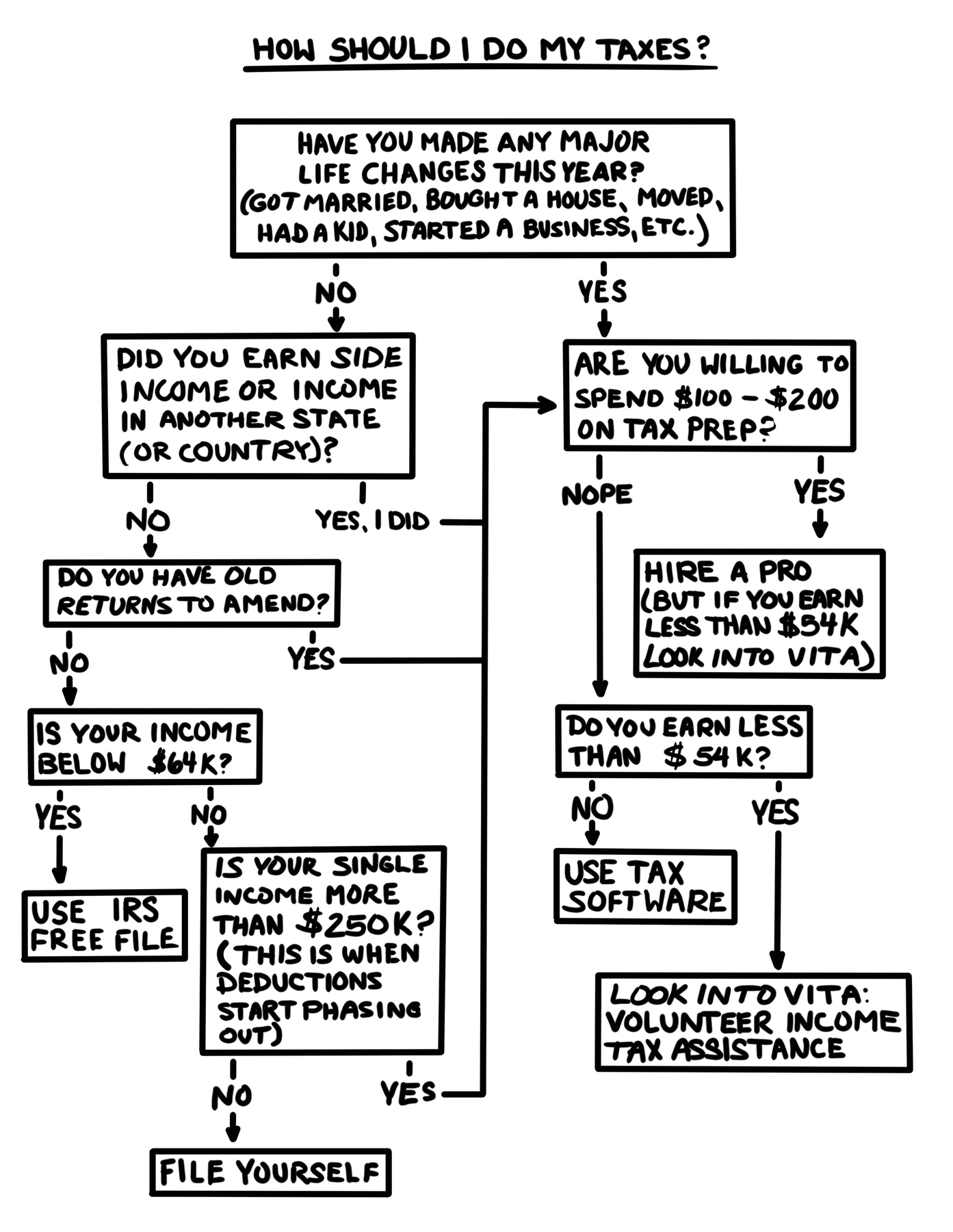

Where to File

Once you have all your forms in order, where and how do you file? You have a few options:

By mail: Fill out IRS forms on your own and mail them in.

Online: Use your phone or computer and file with software from the IRS or a third party.

Tax preparer: Take your forms to a tax preparer and have them do the work for you.

There are pros and cons to each option, of course. The first option is free (and so is the second, if your income is low enough), but if you have quite a few tax forms or a complicated tax situation, it can be a pain. Going to a tax preparer costs money, but it also saves a lot of time. And if you’re going through a major life change, like switching careers, getting married, or buying a house, your tax preparer can help walk you through everything and make sure you’re getting every deduction possible. Online software like TurboTax or TaxAct can be a decent alternative. Some of these online software tools are free if your income falls below a certain amount, and they walk you through each step of the process.

Here’s a brief rundown of each option.

Filing the Old School Way

To file your taxes 100 percent on your own with a calculator and a pencil, you can go to the IRS.gov website to get the forms you need (or just head to your library). You will need one of three forms:

1040EZ: If your tax situation is simple—like if you’re a college student or you’ve recently graduated and you have one job, no kids, and you’re not married—you probably just need a 1040EZ. You qualify to use this form if:

Your filing status is single or

married filing jointly.

Your filing status is single or

married filing jointly.

Your total income is less than

$100,000.

Your total income is less than

$100,000.

Your interest income is less than

$1,500.

Your interest income is less than

$1,500.

You only earn income from wages,

interest, or unemployment compensation.

You only earn income from wages,

interest, or unemployment compensation.

You don’t have any adjustments to

your income.

You don’t have any adjustments to

your income.

You’re only claiming a standard

deduction (not itemizing).

You’re only claiming a standard

deduction (not itemizing).

You are not claiming any other tax

credits, like the premium tax credit (although you’re allowed to

claim the Earned Income Credit [EIC]).

You are not claiming any other tax

credits, like the premium tax credit (although you’re allowed to

claim the Earned Income Credit [EIC]).

1040A: If your tax situation includes a couple of other variables, like you’ve started investing in the stock market or you opened a retirement account, you probably need the 1040A. You qualify to use this form if:

Your total income is less than

$100,000.

Your total income is less than

$100,000.

You earn income from wages,

interest, dividends, capital gain distributions, IRA or pension

distributions, unemployment compensation, or Social Security

benefits.

You earn income from wages,

interest, dividends, capital gain distributions, IRA or pension

distributions, unemployment compensation, or Social Security

benefits.

You are only claiming the standard

deduction (not itemizing).

You are only claiming the standard

deduction (not itemizing).

1040: If you’ve bought a house or you started freelancing on the side, you should probably move on to the standard 1040 Form. You qualify to use this form if:

Your total income is $100,000 or

more.

Your total income is $100,000 or

more.

You’re itemizing your deductions

instead of taking the standard deduction.

You’re itemizing your deductions

instead of taking the standard deduction.

You’ve earned income from a rental,

business, farm, S-corporation, partnership, or trust.

You’ve earned income from a rental,

business, farm, S-corporation, partnership, or trust.

You have

foreign wages or paid foreign taxes, or you’re claiming tax treaty

benefits.

You have

foreign wages or paid foreign taxes, or you’re claiming tax treaty

benefits.

You’ve sold investments like

stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or property.

You’ve sold investments like

stocks, bonds, mutual funds, or property.

You’re claiming adjustments to your

income for educator expenses, tuition and fees, moving expenses, or

health savings accounts.

You’re claiming adjustments to your

income for educator expenses, tuition and fees, moving expenses, or

health savings accounts.

It’s always free to file your taxes on your own and drop them in the mail, no matter your income. You’ll have to crunch the numbers on your own (each form comes with instructions), but you can file without forking over any cash.

On the other hand, when you have a more complicated tax situation that involves using Form 1040A or Form 1040, you probably don’t want to file them on your own because at best, the process can be tedious, and at worst, you might make some mistakes. Filing online is always an option, and it’s also free if you earn less than $64,000.

Filing Your Taxes Online

For federal taxes, the IRS has Free File software for anyone who earns less than $64,000. Only about 3 percent of eligible filers take advantage of this.47 Many states have free online filing options as well, but you’ll have to check your particular state’s tax websites for details. Some have income thresholds to use the service for free, while others will let anyone e-file without paying.

Of course, there are also third-party companies that will walk you through your taxes and then file them on your behalf. TurboTax and TaxAct are probably the most popular options, but H&R Block has an online filing service, too. For simple tax returns like the 1040EZ, these services are generally free. However, if you need help hunting for deductions or you’re self-employed or investing, you’ll have to pay a little extra to have the software walk you through these complicated tax scenarios, and it can cost anywhere from $50 to $115 just to file your federal taxes—a bit more to file your state taxes, too. You’ll have to decide if the convenience is worth it, but if you’re spending upward of $100 to file your taxes online, you might consider going to a professional instead.

Hiring a Professional

If you earn less than $54,000, you might qualify for VITA, the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance service. This is a federal program in which IRS-trained professionals help prepare your taxes. They also offer the service to people with disabilities and to taxpayers who speak limited English. You can look up Publication 3676-B on the IRS website to find a VITA location near you.

If you earn more than $54,000 or you just want to work with someone else, you’ll have to find a tax preparer on your own. You have a few choices:

Certified Public Accountants (CPAs): These are accountants who meet specific state qualifications. If you’re looking for a CPA, make sure they’re comfortable with income taxes, as not all CPAs are income tax experts; some focus on estate planning, for instance.

Enrolled Agents (EAs): Enrolled agents are federally recognized tax professionals who are licensed through the IRS, either by taking an exam or after working for the IRS for five years.

Tax preparation companies: Think franchises like H&R Block. They tend to churn out returns and might not use the most experienced preparers, but the upside is, they’re often cheaper or more accessible than an individual CPA or EA (which might be important if you’ve protaxtinated—yes, I just made up a word—and it’s April 10).

Whatever route you choose, do your research once you’ve narrowed down your choice in preparer. You can check the Better Business Bureau. The IRS recommends asking for a Preparer Tax Identification Number (PTIN) to check the preparer’s credentials and ensure EAs are enrolled with the IRS through the IRS’s Enrolled Agent Program webpage. The IRS also has a searchable tax preparer directory online (irs.treasury.gov/rpo/rpo.jsf). It lists preparers near you who have current, professional credentials recognized by the IRS.

It’s important to make sure you’re working with a quality, qualified preparer because, at the end of the day, you’re still responsible for your taxes. If your preparer screws up, it’s still your problem.

Refunds: Why They’re Not Actually That Great

It feels good to get a nice big check or direct deposit from the IRS, doesn’t it? And as you learned in Level Nine, you can use this money to boost your financial goals, like paying down debt.

It sounds great, but tax refunds aren’t actually that wonderful. When you get a refund from the IRS, they’re just giving you money that you overpaid. It’s not “extra” money—it was your money to begin with! This isn’t a big deal if your refund is a hundred bucks or so, but if you’re getting hundreds or thousands back, you’re overpaying a fair amount throughout the year. A common complaint about this is, “It’s like giving the government a tax-free loan.” The idea is, you can save your hundreds or thousands in your own account and earn interest on that money instead. Let’s be a little realistic, though. How much are you really going to earn on that money? Bank interest rates are painfully low (at most about 1 percent), so the answer is: not much.

However, there is one instance in which overpaying hundreds or thousands throughout the year is a bad idea: when you have debt. Think about it. If you could pay off your debt with that money throughout the year, how much more could you save in interest? Many debts, whether loans or credit card balances, carry an interest rate of at least 10 percent. It doesn’t make much sense to overpay your taxes throughout the year if you’re trying to supercharge your debt payoff.

Keep in mind, though, that if you don’t pay enough taxes at the end of the year, not only will you owe the IRS money, you may also have to pay a penalty for underpaying. So there’s nothing wrong with erring on the side of caution and getting a little bit back in April. However, if you’re overpaying by thousands, it might be time to adjust your W-4, the tax withholding form you filed with your employer when you started your job.

How to Fill Out and Adjust Your W-4

When you start a new job, your new employer should give you a W-4 IRS form. If you’ve been paying attention (which is hard to do with a topic like taxes, so kudos), you know this form tells your employer how much money to withhold from your paycheck for taxes. (See a video tutorial on how to fill this out at www.TheGetMoneyBook.com.) Your W-4 also includes three different worksheets:

The Personal Allowances

Worksheet

The Personal Allowances

Worksheet

The Deductions and Adjustments

Worksheet

The Deductions and Adjustments

Worksheet

The Two-Earners/Multiple Jobs

Worksheet

The Two-Earners/Multiple Jobs

Worksheet

All these worksheets give your employer the information they need to calculate how much needs to be withheld from every paycheck. If you’ve never filled out a W-4 before, the form includes instructions to help you do it, but it involves a few simple steps:

Step One: Decide If You’re Exempt (You’re Probably Not)

If you’re exempt, that basically means you’re not on the hook for income taxes, aside from Medicare and Social Security. You can only claim to be exempt if your income is so low that you expect to have no tax liability for the current year and you weren’t on the hook for taxes last year. Chances are, you’re not exempt, but you can use the IRS Interactive Tax Assistant to figure that out online. If you are exempt, you’ll simply write “Exempt” on Line 7 of your W-4. Don’t do this unless you actually qualify, though, or you’ll be in for a nasty surprise in April.

Step Two: Calculate Your Allowances

The Personal Allowances worksheet tells you how many allowances you can claim, and it should be fairly straightforward. This is also the part of the W-4 form you’ll want to adjust if you want a smaller tax refund. Generally, the fewer allowances you claim, the more money gets withheld from your paycheck. So if you want to pay less throughout the year and avoid a gigantic refund, you’ll probably want to claim more allowances. If you claim too many allowances, though, you might end up underpaying your taxes. This is why it’s probably best to follow the form’s instructions and claim what it suggests until you actually see how much you owe or get back in April; after that, you can adjust your withholding accordingly.

Step Three: Add Your Deductions and Credits

The Deductions and Credits worksheet helps ensure you include any tax benefits that might reduce your overall taxable income. This gives your employer an even better idea of how much you might owe so that you don’t overpay. If you itemize your deductions (we’ll get to that in a bit), make sure you fill out this form. You might have education credits or mortgage interest you’ll want to calculate using this form, too. The more deductions and credits you take, the less your employer will withhold.

Step Four: If You Have Multiple Incomes, Fill Out the “Two Earners” Worksheet

Let’s say you have two jobs or you’re married and your spouse works, too. This worksheet helps you figure out how much more you should withhold from your paycheck considering that second income.

All these worksheets are pretty straightforward and come with line-by-line instructions on how to fill them out. If you need to adjust, though, you’ll have to request the form from your employer and fill out a new one. Remember, the general rule is more allowances mean less money withheld for taxes: more allowances, bigger paycheck, smaller tax refund.

HOW TAXES WORK FOR FREELANCERS

Ah, taxes and freelancing. They go together like nausea and road trips. Or torn-up feet and cute heels. Or hangovers and tequila. In other words, they’re the totally ugly but inevitable side of something that most people don’t consider before embarking upon it.

When you’re a freelancer, you do not fill out a W-4. You fill out a W-9 for each client instead, which tells the client who they’re paying so they can report that payment to the IRS. If your employer gives you a W-9, you are not technically an employee—you are an independent contractor or freelancer. For tax purposes, this means you’re responsible for paying your own income taxes, self-employment taxes, Social Security, and Medicare throughout the year. Your employer will not withhold taxes from your paycheck or pay the IRS on your behalf. Pay attention to what kind of form you sign when you start a job, because this is where estimated quarterly taxes come in.

Estimated Quarterly Taxes

Four times throughout the year, freelancers and independent contractors must pay estimated quarterly taxes. The IRS releases an updated schedule each year (taking things like weekends and holidays into account), but these are typically due on April 15, June 15, September 15, and January 15 (of the following tax year). If you don’t pay enough at the end of the tax year, you’ll owe the IRS money for taxes plus penalties, just like I did when I depleted my emergency fund.

When you start filing your taxes as a self-employed freelancer or independent contractor, the IRS will send you Estimated Tax Payment vouchers that you can treat just like bills. IRS Form 1040-ES also includes a worksheet with instructions (and if you use tax software, most programs can help you do this, too). Write a check for the established amount, then send it off by the due date. You can also make payments online via the IRS Direct Pay tool. But first, how do you make this estimate to begin with?

Well, the IRS has pretty clear rules on how much you have to pay to avoid penalties. That amount is either:

100 percent of the tax you paid

last year (or 110 percent, if you earn more than $150,000 for the

year), or

100 percent of the tax you paid

last year (or 110 percent, if you earn more than $150,000 for the

year), or

90 percent of the tax you will owe

this year (even if you don’t know that number yet).

90 percent of the tax you will owe

this year (even if you don’t know that number yet).

In most cases, it’s probably best to shoot for 100 percent of last year’s taxes, just to be safe and avoid an underpayment penalty. This penalty isn’t huge, but still: who wants to pay money they don’t have to pay?

If You’re Freelancing on the Side

Let’s say you don’t earn much from your freelancing business and/or you’re working full-time and freelancing on the side. Hate to break it to you, but you probably still have to pay taxes on this amount. If you earn over a certain amount for the year, any employer, client, or company is supposed to send you a tax form indicating how much you earned. If you’re a freelancer hired by a company, that form will typically be a 1099-MISC. If you have an Etsy business or you drive for Uber, you should get a 1099-K. For 2017, businesses are supposed to send a 1099-MISC form if the contractor earned over $599. For companies that send 1099-K forms, they’re typically required to send them for earnings over $20,000 or for more than two hundred transactions within the tax year. That said, if you don’t meet these thresholds as a freelancer, that doesn’t mean you don’t have to pay taxes. “Note that all your earnings, regardless of how small, are subject to income tax,” says Kay Bell of Don’tMessWithTaxes.com (best URL ever). “That includes payments you get but for which you never get any documentation, such as a 1099 form.”

The IRS makes it clear that you’re responsible for tracking and reporting everything you earn, regardless of whether you get a tax form. Basically, if you make money, Uncle Sam wants his cut. There’s one exception to this rule in the gig economy, though. If you have an Airbnb property and only rented it out for fourteen days or less, you don’t have to report this. However, you can’t deduct any expenses related to your Airbnb income in this case, either.

If you’re working full-time while you’re freelancing, it’s time to rethink your W-4. Make sure you withhold enough to cover the taxes you owe from your side gig or freelancing business. The “Two Incomes” worksheet can walk you through this, or you might consider reducing your allowances. However, if you typically get a big refund from the IRS, chances are, that will cover the extra amount you owe in taxes. In other words, that refund will likely cover your butt your first year freelancing, and when you actually do your taxes in April, you can get a better idea of how much you should withhold going forward.

Fair warning: this move is hugely dependent on how much you earn and how much you withhold. If you earn a large sum of money on the side, you likely need to withhold more and adjust your W-4 accordingly. Check out the IRS.gov website for a withholding calculator and Form 1040-ES, which helps you figure out your estimated taxes. Both of these resources can give you a better idea of how much you should withhold. Better yet, this is a perfect time to talk to a tax professional or Certified Financial Planner who can help you understand your own unique situation.

PRO TALK: Kay Bell, Journalist and Founder of DontMessWithTaxes.com

HOW DO TAXES WORK WHEN YOU HAVE A SIDE GIG?

Many self-employed individuals, especially early in their entrepreneurial career, start off filing as sole proprietors. Here you report your self-employment income on Schedule C and attach that to your annual Form 1040 filing. If you are making the money as a side gig, Schedule C is also the form for you. And if you have several different freelance enterprises, such as driving for Uber and tutoring high school students and writing articles for a website, then you’ll need to fill out a separate Schedule C for each.

Schedule C and its instructions give you a good idea of what you can claim as a business tax expense. Make sure you take as many as you qualify for. And make sure you keep good records of all your business expenses.

If your side gig work isn’t that complicated, you might be able to file Schedule C-EZ. There’s also an easier version of Schedule SE you might be able to file.

Take your tax filing of your self-employment income as seriously as you do your gigs. Self-employed Schedule C taxpayers are often a prime audit target because in many cases their income is hard to verify.

The IRS trusts you to be honest about your earnings and deductions. But if something looks unusual, you can bet that a tax examiner will ask questions about it.

Don’t, however, let that scare you off working for yourself. Again, the key is keeping good records of your income and expenses. If you have the proper documentation, you can easily answer any IRS auditor questions.

THE BREAKS: DEDUCTIONS, EXEMPTIONS, AND CREDITS

Like most taxpayers, tax breaks are maybe the only reason I ever look forward to doing my taxes these days. These are deductions, exemptions, and credits that can lower your taxable income so you’ll pay less in taxes. So what’s the difference between the three: deductions, exemptions, and credits?

Tax Exemptions

Tax rules allow you to take personal exemptions or dependent exemptions, which allow you to subtract a certain amount from your taxable income. A dependent exemption allows you to deduct a specific amount for each individual you’re responsible for financially, such as a child. The amount of this exemption for 2017 was $4,050.

A personal exemption is available if you’re single, you don’t have dependents, and no one can claim you as a dependent. If you are married, you might be allowed one exemption for your spouse, too. Again, the amount of the exemption was $4,050 for 2017. Your exemption starts phasing out once you earn a high income, though. For 2017, that amount was $259,400 for single filers.

Tax Deductions

The government also lets you deduct some of your own expenses from your taxable income. There are two basic types of deductions. First, there’s the standardized deduction, a fixed amount the government calculates to make it easy (for 2017, that amount was $6,350 for single filers and $12,700 for married couples filing jointly). If you have deductions that total more than the standard amount, you might consider taking an itemized deduction, which is pretty much what it sounds like: a list of all the items, or expenses, that you’re allowed to deduct. These expenses include:

Your home mortgage interest

Your home mortgage interest

Your property taxes

Your property taxes

Charitable donations

Charitable donations

Job search expenses

Job search expenses

Work-related expenses, including

your home office

Work-related expenses, including

your home office

We’ll dig more into these deductions in a bit, because many workers leave money on the table by not maximizing them. There’s also a student loan interest deduction, which you can take no matter which option you choose, standard or itemized. If you’re paying a student loan, you’re probably paying interest, so don’t forget to take this deduction.

Tax Credits

While tax exemptions and deductions reduce your taxable income, tax credits are actually subtracted from the tax you owe, making them even more beneficial. Some of these credits include:

The Child Tax Credit: A credit of up to $1,000 for each qualifying child.

The American Opportunity Tax Credit: A credit for qualified education expenses for an eligible student within the first four years of their higher education. The maximum annual credit is $2,500 per eligible student.

The Lifetime Learning Credit: A credit for qualified tuition and related expenses paid for eligible students who are enrolled in an eligible institution. There’s no limit on the number of years you can claim the credit, and you can claim up to $2,000 per tax return.

There are also credits for low-income taxpayers, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the amount varies depending on income. The Saver’s Credit is for taxpayers who have an adjusted gross income of less than $31,000 (or $46,500 if head of household; $62,000 if married filing jointly for the 2017 tax year) to encourage them to save for retirement.

If you work with a tax preparer or use tax software, it should be easy enough to figure out which tax breaks you can take—they’ll do the work for you. Still, it doesn’t hurt to explore all these options.

Business Deductions You Should Know About

If you’re self-employed as a freelancer or independent contractor, you can also deduct your business expenses using the IRS Schedule C for sole proprietors. These deductions are separate from your personal deductions, and Schedule C is used to report any income or loss from your business. If you’re working with a tax preparer or using a tax software program, they should walk you through the many deductions you can claim as a self-employed worker. No, you can’t deduct lunch with your boyfriend, even if he did ask you about work (unless maybe he’s also your client), but you can deduct plenty of other expenses.

So how do you know what kind of expenses are deductible? According to the IRS, in order to be deductible, a business expenses has to be both “ordinary and necessary.” In other words, it has to be an expense that’s common and acceptable in your line of work and also useful for operating your business. Here are a few examples of expenses you can deduct:

Your home office: The IRS allows self-employed people to deduct a portion of their mortgage or rent payment for a home office. To qualify, though, you have to have a designated area in your home just for work. The IRS has specific ways they calculate this deduction based on the square footage of your home and home office.

Office equipment and supplies: Computers, chairs, printers, and any other business-related equipment or expenses are deductible.

Travel: The IRS allows you to deduct a portion of “ordinary and necessary expenses” of traveling away from home for your business or job. This could include flights, hotels, and transportation costs.

Your website: You can deduct the cost of running a website for your business.

Advertising: If you print business cards, flyers, or anything else to advertise your business or services, these are deductible, too.

These are just a few business-related deductions you can take. As a general rule, if it’s an expense that’s both “ordinary” and “necessary” for your business to turn a profit, you can deduct it. The IRS defines a necessary expense as one “that is helpful and appropriate for your trade or business.” If you work in the gig economy, don’t forget to deduct certain expenses related to your gig, whether it’s using your smartphone to pick up customers or buying cleaning supplies to keep your Airbnb tidy for guests.

Again, a tax preparer and tax software can help ensure you get all the deductions you qualify for. I’m also a fan of 99Deductions.com, an interactive web app that asks about your freelance profession to walk you through common deductions you can take.

WORST-CASE SCENARIO: YOU CAN’T PAY

Remember my terrible tax story from earlier? What if I didn’t have that emergency fund saved? What would I have done?

Not being able to afford your tax bill is a nightmarish scenario. While the IRS does allow credit card payments through a processor, that’s a desperate scenario you want to avoid at all costs. Not only will you pay interest on your credit card, but the IRS charges you a fee to use the third-party credit card processor, too. You have a couple of options to explore before going into full-on desperation mode.

First, you might be able to settle for a smaller amount with the IRS with an “Offer in Compromise.” For a $186 application fee, you can fill out IRS Form 656 and request to settle your tax debt for an amount that’s less than what you owe. But you’ll have to prove financial hardship. In determining this, the IRS considers your: ability to pay, income, expenses, and the value of your assets. If your offer is accepted, it goes on your public record, but it doesn’t affect your credit score. That $186 fee isn’t cheap, so use the IRS Offer in Compromise Pre-Qualifier tool on their website. The tool will tell you how likely you are to qualify and, if you do, how much you should offer to settle.

Alternatively, you could ask for a payment plan. Individuals who owe $50,000 or less in combined individual income tax, penalties, and interest are eligible as long as they’ve filed their returns. You can fill out an online payment plan application via the IRS website. Or you could fill out and mail IRS Form 9465, an Installment Agreement Request, along with Form 433-F, Collection Information Statement. Instructions are included on the forms. Otherwise, you can call the IRS at 800-829-1040 or at the phone number on your tax bill or notice.

HOW TO FILE AN EXTENSION

If you need more time to gather your tax paperwork, you have the option of filing an extension, but don’t get too excited: you still have to pay your taxes on time. “The extension is only for more time—six months, precisely—to file your Form 1040 (or 1040A or 1040EZ),” says Kay Bell. An extension doesn’t give you more time to pay your taxes. “You still must pay any tax you owe by the April deadline or face interest and penalties on the unpaid portion.”

You can file an extension the old-fashioned way, by sending in a paper form, or electronically. To avoid fees and penalties, Bell suggests the following steps:

First estimate the tax you’ll owe for the year’s filing. “To come up with the most accurate amount, look at how much you’ve already paid in taxes (e.g., through withholding and estimated tax payments),” Bell says. “Then determine how much of that you can pay. Making a good estimate and paying as much of that as possible will help reduce any penalty and interest charges that could come from underpayments.”

Then decide how you want to request your filing extension. If you submit by mail with IRS Form 4868, the envelope has to be postmarked by midnight on tax deadline day. If you e-file or e-pay any tax due, you also have a midnight deadline.

“Check out the IRS e-file options web page for ways to make an electronic extension request,” Bell says. “If you’re going to electronically pay the amount of tax you believe you owe, take a look at the IRS e-payment page. There you’ll find the many ways you can pay what you owe.”

If you’re struggling, pay as much as you can. Bell says it’s important to just pay any amount by the deadline to let the IRS know you’re aware you must eventually settle your bill.