She slept for a long time. Life on the plantation continued its pattern: The mules pulled the rattling wagons to the fields and back, the chickens and geese pecked at bugs around the smokehouse. Meals were cooked, chores were begun and completed. Garden spiders wove webs in the crape myrtles. Bees visited the okra and squash blossoms. Viridian hoverflies darted among the rosemary and lavender and lemon balm in the herb garden. The live oaks sent long shadows toward the west, then to the east.

Celeste finally awoke to the sound of shouting voices coming from downstairs. One of them she knew was Joseph’s voice, and she scampered down the attic steps, pausing at the knothole; she feared the cat might be lurking nearby. Light from an oil lamp glowed beneath Joseph’s bedroom doorway. Loud voices mixed with a shrieking, screeching call and the sounds of flapping feathers.

“Tie him, quickly!” shouted a deep voice. She recognized it as Audubon’s. “And tightly! Here!”

After more scuffling sounds the room quieted. Celeste started across the hallway, then hesitated.

“Ah, yes. He’s a beauty!” said Audubon. “Mr. Pirrie isn’t a bad shot after all!”

Then she heard Joseph. “And he’ll heal up fine. He’ll be a great live model for the osprey painting.”

Osprey! Celeste thought in alarm.

Audubon paused. “Yes,” he said. “There is something about this one…. He has spirit.”

Suddenly the bedroom door swung open, and Audubon and Joseph entered the dim hallway. “Once you’ve gotten the supplies we need in New Orleans, return straight back, Joseph,” Audubon was saying. “If you leave tonight, you can be back by Saturday.”

“Yes, sir.”

Leaving? thought Celeste. Going away? She felt panicky inside.

Joseph glanced back into the room, searching for something.

“Where did she wander off to?” he asked.

Audubon arched an eyebrow. “Who?”

“My little helper. Little One. She’s disappeared. I put out some nuts for her, but she’s gone.”

“Perhaps the cat got her.”

“No, she’s much too keen for that to have happened. But I feel a little lost without her, without her in my pocket. She’s my companion, my…friend.”

“Well, I’ll keep an eye out for the little mouse; you get on your way to New Orleans.”

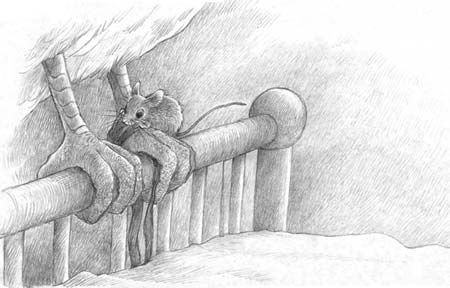

Celeste pressed against the wall, avoiding the heavy shoes as Audubon and Joseph strode down the hall. She wanted to squeal and squeak and run after Joseph; but she hesitated, fearing the giant Dash, who trotted at their heels. They turned the corner, then clomped down the stairs, their voices dimming as they headed out the front door.

Again Celeste heard flapping sounds from the bedroom, then the crash of an object falling and pieces of something scattering on the floor. The flapping stopped.

She peeked around the door.

There, tied to the footboard of the bed, was a large brown-and-white bird. It turned its sunflower yellow eyes toward Celeste.

A familiar voice squawked, “It’s impolite to stare, you know!”

“Lafayette! What happened? What are you doing here?” Celeste raced across the floor and up to the bed rail, and gave the osprey a hug around his leg.

Lafayette grinned. “I’m glad to see you, too, dumplin’.”

“But I heard such a commotion! I had no idea it would be you!”

“You’d make a commotion, too, honey pie, if you were tied up. And look at this.” He gestured to a putrefying catfish head nearby. “They expect me to eat that? That fish has been dead longer than my Great-aunt Mabel, and I’m getting just a little bit tired of the stink!”

Celeste sniffed in agreement.

“You’re wonderin’ how I got myself here, am I right, lamb chop?”

“Oh, yes!”

“Well, there I was, mindin’ my own business after droppin’ you on the windowsill, had barely gotten any distance at all, and the next thing I know, BOOM! Some crazy maniac down in the yard is jumpin’ around and wavin’ his gun and laughin’! My wing is missin’ some feathers, and down I go. I got a good jab at somebody’s hand, though…. You should have seen the blood! Now I’m tied up here…tied up because my good wing is strong enough to get me up in the air…. I’d try to take off right now if it weren’t for these straps.”

“What are they going to do with you?”

“Over there on the table are his sketches. He spends hours studyin’ me and scribblin’ on sheets of paper. Then he gets all flustered and stomps off. Meanwhile, here I sit with Mr. Stinky B. Catfish, and I’m about to go crazy!”

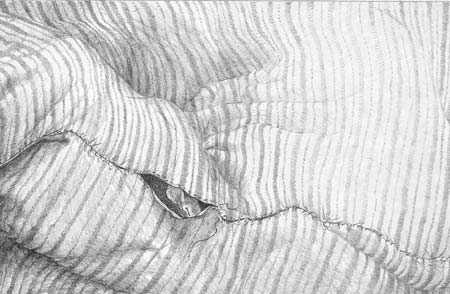

Celeste noticed the thick leather strap that tied Lafayette to the footboard.

“Perhaps I could chew through those,” she said. “The window’s open. You could just fly out.”

“You could do that?”

“Of course!”

“Excellent idea!” Lafayette exclaimed. “Start chewin’, sugar pie!”

Celeste scrambled over and, sitting on Lafayette’s left foot, began to gnaw. It was difficult; the leather strap was hard and tough. In half an hour she was only partway through the strap.

Just then they heard the slam of the screen door downstairs and the heavy sound of boots coming up the stairs.

“He’s back.” The osprey sighed. “The bigger one. I can tell by the footsteps.”

Celeste darted across the bed and leaped over to a nightstand, hiding behind the washbasin.

The tall, imposing figure of Audubon appeared in the doorway. He stood with hands on hips, the thick shank of auburn hair hanging to his shoulders, studying Lafayette in the lamplight.

Lafayette glowered back, sitting hunched and tense. He had had enough of this man who sat watching him for hours and hours, scratching lines on paper.

“We begin again,” Audubon said, grabbing his supplies and sitting on a stool in front of the osprey.

From her hiding place Celeste could see over Audubon’s shoulder. His eyes were fixed on Lafayette. Pencil line after pencil line covered the large piece of paper. Over and over the lines were erased, then begun again.

The room was hot; Audubon’s face glistened with perspiration.

Lafayette’s anger slowly gave way to boredom. He sat on the bed rail half asleep.

Celeste watched Audubon’s hand, fascinated. The way it glided and flowed across the paper reminded her of her own paw as it moved in rhythm when she was weaving.

Suddenly it stopped. The pencil fell to the floor as Audubon dropped his face into his hands and sighed with exasperation, shoulders slumped.

“Mon Dieu,” he moaned. “My drawing is all wrong.” He stood up, sheets of paper spilling off his lap. He paced the room several times, thinking, his chin in his hand.

“Perhaps,” he said, contemplating Lafayette yet again, “I need to pin your wings up, holding them in place…and then your head needs to be wired upright…. I could make a better painting….”

Celeste nearly squeaked in alarm, peeking out from behind the washbasin.

But Audubon picked up his pencils; again there was the sound of graphite scratching on paper, then he suddenly stamped his foot.

“Ça n’est pas possible!” his voice erupted. “There is no life in this portrait! This osprey might as well be dead and stuffed like a Christmas goose! The wings are folded like it is in a casket! And the eyes…dull! The neck…stiff! The feet…how you say it? Crooked! I cannot get it correct. My paintings are as blank and lifeless as the portraits of Monsieur and Madame Pirrie in the dining room downstairs!”

There was a clatter of pencils being thrown across the room as Audubon stormed out. The large piece of paper drifted to the floor, sliding nearly to the door. Celeste ducked a little closer into the shadows, but she could see the lines of a large bird drawn on the paper.

Celeste studied the drawing. She had a plan. It had worked before, and it would work again.