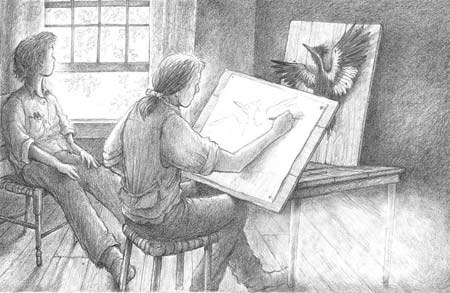

Another afternoon, another lesson. Audubon’s hand glided across a sheet of paper, guiding a stick of charcoal.

“Observe,” he commanded. The charcoal scratches eventually formed the outline of a crested head, a beak, and the posed body and wings of the ivory-billed.

Joseph sighed, trying to muster up interest in the lesson. To him, trying to listen to Audubon’s instructions sometimes felt like pulling nails out of a plank. Instead of watching the charcoal, he stared out the window. He was wishing both he and Celeste were out exploring the woods around the plantation, looking for plant specimens.

Celeste’s nose twitched as she watched from her pocket perch. The odor of putrefying flesh had begun to hang closely in the hot room, and flies hovered constantly around the bird.

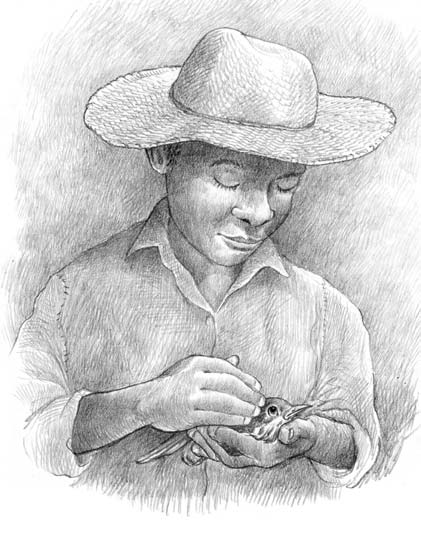

They heard shouts below the bedroom window. Two young boys, the sons of one of the farmhands, were outside in the yard. The older one clutched something carefully to his chest.

“Mr. Joseph! We got something for you!” he cried out. With excitement, he cautiously revealed a tiny portion of a feathered body. “It’s a bird! Everybody says you wants to get birds. Well, we got one for you!”

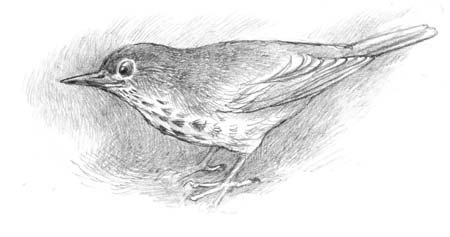

Joseph raced outside and gingerly pulled back more of the old shirt. He saw a yellow bill and soft, creamy white breast feathers spotted with dark brown. “A wood thrush,” he murmured. “Beautiful! Thanks, boys!”

“We found him in the lower barn. He must’ve flown in and couldn’t get back out. It was easy catchin’ him. He was scared.”

“It was easy!” the younger boy agreed.

“Well, nice job, boys. This thrush will make for a beautiful painting.” He gave the boys a coin from his pocket, and they ran off.

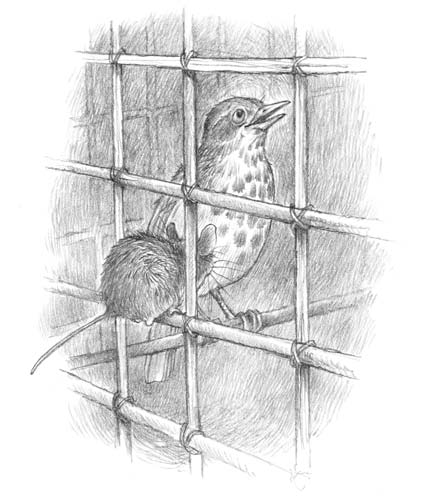

The little wooden cage soon had a new occupant. The panicky thrush, which probably had never been enclosed in anything smaller than the lower barn, now beat its wings against the twig bars, fluttering nervously about the cage. Thankfully, as night fell he became quiet.

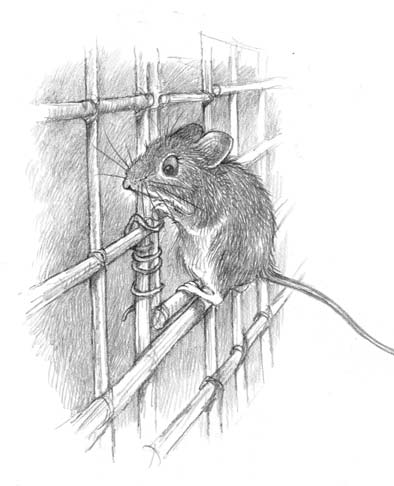

The next morning, after Joseph had gone outside to wash, Celeste scrambled down the shirt to the floor and then carefully clawed her way up the brocaded drape and leaped to the tabletop.

“Hello!” she said to the thrush.

“Hello!” the thrush called back. His voice was low and silvery.

“May I introduce myself,” began Celeste. “My name is Celeste, and I live in this house.”

“I’m pleased to meet you,” replied the thrush. “My friends call me Cornelius…. I’d be honored if you did the same.”

“Thank you! Pleased to meet you, Cornelius.”

“I live…well, I did live in the woods near here. I can’t tell you how horrible it is to be trapped inside this cage after a lifetime of flying free. How good are you with escape plans, Celeste? I’ve worn myself silly trying to fly in between the bars of this cage, and lost some feathers in the process, as you can see.” He looked up. “What about that little door?” Cornelius suggested. “Can you climb up there and unlatch it?”

Celeste squinted up at the cage door. “Hmm…” she said. “Just maybe…” She clawed up one of the bars of the cage to the latch. She tried undoing the wire clasp, but it was tightly twisted. “I might have better luck just chewing through the bars,” Celeste said. “It would take me a few days to make a hole big enough for you to squeeze through, but I’m sure I could do it.”

Cornelius looked at her. “How did you come to live here?” he asked.

Celeste scampered down the side of the cage. No one had ever asked her that; she hadn’t thought about her journey to the house at Oakley Plantation in a long time. She looked at Cornelius; his eyes were clear and thoughtful. Celeste could see that even though trapped in a cage, Cornelius was interested in his new friend.

“Well,” she began, “I guess you could say I was rescued.”

“Rescued? From what?”

Celeste thought back. There were details of her childhood she could barely recall; she remembered a nest made of grasses in a tangle of timothy hay and wildflowers. She remembered three brothers and a sister, and a doting mother and father.

After a moment Celeste spoke. “My very first memory is of my mother. ‘Francis, Silas, Beau, Louisa…’ she would say, nudging my brothers and sister. ‘Let Celeste in.’ And I would wiggle and squirm until I had a spot at my mother’s soft warm tummy to nurse.

“I remember all of us rolling and tumbling around our nest…a cozy dome of grass. There was a forest of grasses and weed stalks all around outside, and we’d explore it together. That’s when I found I could twist and weave blades of grass together; my mother showed me how.

“Then one afternoon I was out gathering grasses. I shouldn’t have been out of the nest, where the rest of my family was napping. It was a hot day. I heard human voices somewhere off in the field; they were singing. The voices got closer, and I heard another, strange, swooshing sound. As I raced back toward the nest, the tall, shady grasses were suddenly cut clean to the ground; there was this horrible glare and the heat of sunlight everywhere…. Our home had been sliced open by a long, curved blade. I saw the blade; it glinted in the sun and then swept back, slicing through the grasses over and over.”

Cornelius hopped closer to the edge of the cage. “What happened then?”

“Well, I don’t remember much after that, just lots of squeals and cries for help and frantic scrambling for safety. But after the humans had passed on, I was the only one left alive. I was wounded; I had been stepped on by one of the humans.”

“But how did you end up here, in this house?”

“Nighttime came; I was still lying there in the drying hay. I remember it smelled so sweet. I was waiting to die, really…. I was so weak. I heard a rustling, and a groundhog lumbered up. I was too hurt and tired to say or do anything; but the groundhog—his name was Ellis—he carried me on his back, and brought me here to the house. He lived in a tunnel under the stone foundation. He gathered fresh grasses and things to nibble on until I got better. I learned how to live in the big house from two rats; they showed me how to find food. Without my family, there didn’t seem to be any reason to live in the fields again, so I decided to stay here for a while. That was many months ago…. I never left.”

“What happened to Ellis?” Cornelius asked.

“I’m not sure; one day I heard shots from outside, and I never saw him again. I don’t know if he was hurt or just chased away. He was a good friend.”

She paused for a moment, thinking. She hadn’t ever permitted herself to bring up memories of that day. It felt good to tell Cornelius.

“Thanks for listening,” she said. “I didn’t mean to go on and on. My plan now is to get you out of this cage…. But in the meantime, can I bring you anything? Something special that you like to eat perhaps?”

Cornelius replied excitedly. “Something like dogwood berries? The dogwood berries are beginning to ripen, and I haven’t had one since last fall. I noticed a dogwood tree in the yard, just next to this house, with red and green berries all over it. Dogwood berries would be lovely!”

“That should be simple enough,” said Celeste.

“You could do that?”

“I’ll see what I can do. I can try finding some once it gets a little darker outside.”

“Wonderful. Being in this cage is a nightmare! You’ve given me…well…a little glimmer of hope.”

The wood thrush then lifted his head and let loose a startlingly clear warble that resonated throughout the room. The beauty of it made Celeste’s chest give a tiny heave; and she felt a pang, and an ache so intense that her heart skipped and trembled. She clutched at it with her paw.

The lilting birdsong ended, and the room was still.

“I don’t know which I like better,” Celeste whispered, “your beautiful song, or just after.”

The thrush smiled.

“Do that for Joseph,” Celeste stated firmly. “Sing just like that. Promise me.”

Cornelius shrugged his wings, then nodded.