The crickets and cicadas were beginning their chorus. Supper was being served downstairs in the dining room.

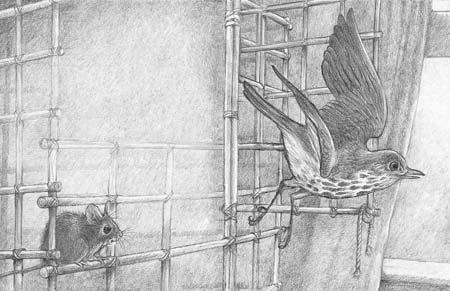

Celeste balanced her way up the dogwood branch, using it like a ladder to reach the cage door latch. The branch was just tall enough. “Hey!” she squeaked in delight. “The wire is gone! What happened?”

The twisted wire that had held the cage door closed had been replaced by a small length of rope, looped and knotted several times around the twigs.

“Good news! The wire snapped when the boy was opening the cage yesterday, so he latched the door with a piece of rope.” Cornelius explained. “Isn’t that better? Can you untie it, or nibble through it?”

“You bet I can!” It took a while, but Celeste bit and yanked, chewed and gnawed until finally the cage door swung open.

“Freedom!” Cornelius trilled. In a flash he was through the cage door and circling the room.

Celeste leaped over to the drawing desk, and Cornelius settled near her on the windowsill.

They looked at the watercolor painting on the desk: a wood thrush was stretching up to eat a dogwood berry. The painting was soft, with cinnamon browns and forest greens.

“It looks just like me,” marveled Cornelius.

“It does, indeed. Now you’ll live forever in a painting.”

“Maybe he’ll paint you next…. When I come back, you can show me your portrait!”

“Come back? Come back from where? Where are you going?”

Cornelius looked earnestly at his friend. “I’m going away, flying south. I go away this time every year. I’m leaving very soon; in fact, that’s why it’s so perfect that I’m out of that cage now.”

Celeste felt panicky. “But why? Why do you have to go?”

“We all go,” Cornelius replied. “All the wood thrushes. We go to where it’s summertime all year round.”

A group of thrushes suddenly flew into the magnolia outside, spilling among the branches and chattering. Celeste and Cornelius looked at each other.

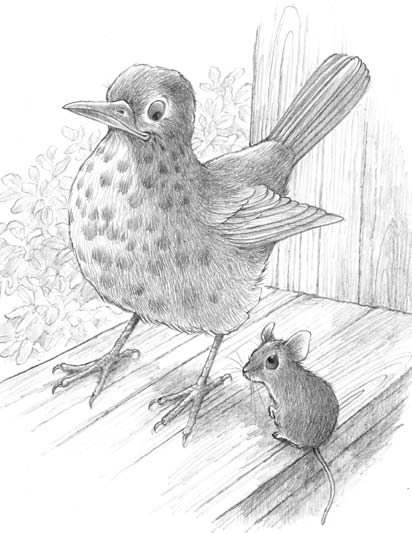

“Well, I guess this is farewell, for now,” Cornelius said.

Celeste hadn’t counted on this. She was nearly overwhelmed with a heaviness of heart; she was going to miss her friend. Her eyes began to burn, and a tiny tear spilled out.

“Yes, I guess so,” she replied. Her throat tightened, and her ears folded back. “When will you be back?”

“In the spring.” But Cornelius seemed distracted and slightly agitated. There was something powerful inside him, a compass in his brain, telling him: Fly south.

Celeste scrambled up the drapes to the sill. She looked at the thrush for a moment and held out her paw to stroke the soft feathers of his cheek.

Cornelius stretched one wing, then the other. His eyes were bright. He spread his tail feathers, testing them. He was ready to go. He needed to go; instinct was telling him so.

“Good-bye,” he said softly. “And thank you. You’re a good friend.”

His wings opened; and he dropped from the sill, arching dizzily in the air below the window, then out and beyond the garden hedges, gathering with the other thrushes. The flock of them circled around, and Cornelius looked back to glance once more at Celeste. He called out, “Good-bye! Good-bye! See you in the spring!” and off he flew, flapping and looking very happy, almost giddy.

Celeste watched the flock of thrushes get smaller and smaller. She tried to follow Cornelius with her eyes, but the birds crisscrossed and wove among one another in the air, and soon she couldn’t tell which of the tiny, disappearing dots was her friend.

Was this a part of friendship, too? The hardship of saying good-bye? Suddenly her eyes blurred…but just as suddenly her skin felt prickly. Her whiskers twitched.

She wasn’t alone.

She looked down.

Something had heard her cries. There was the cat, eyes black and focused, hind legs poised and ready to lunge.