16

THE LAND OF MILK AND HONEY

If I had wings, I would fly.

An elderly woman returning to her home after

decades of being forced to live in the homeland of Bophuthatswana,

to which she had been removed under grand apartheid’s social

engineering.

22 April 1994

On the day of Ken’s funeral, I underwent my fifth

operation in five days. It was difficult to concentrate and even

more so to differentiate between reality and hallucination. My

points of reference were the operations: the surgeon would loom

over me saying that the flesh around the wound had continued to die

off, and that he needed to operate yet again. The nauseating

gurney-ride through the corridors to the operating-theatre would

dissolve and the next lucid moment was one of emerging from the

anaesthetic, pain eating into my chest, until the next blessed

injection of morphine would ease me back to a dissociated, narcotic

world.

Every day, friends would come visit, but the stream

of visitors blurred. I forgot who came to see me, and what they

said, what I said. I was drifting between substance and illusion.

But there was one moment of absolute clarity, when Ken’s mother,

Geri, came in with a bunch of red roses from the funeral, their

buds on the point of opening, and said, ‘Ken would have wanted you

to have these.’ Though I don’t

particularly like roses, I kept them for months.

Alwyn Wolfaardt, a member of the extreme

right-wing Afrikaner movement (the AWB) begs for his life shortly

before being executed by a Bophuthatswana policeman after an

abortive attempt to prop up the tyrannical regime of the homeland

of Bophuthatswana, March 1994. (Kevin Carter/Corbis Sygma)

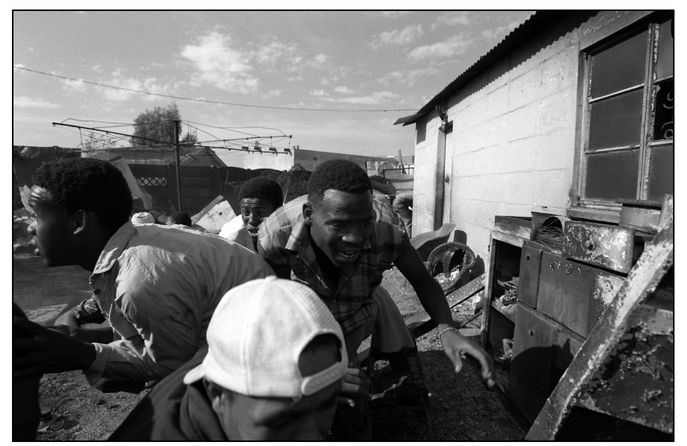

Journalists run from the scene of the execution of

the AWB members, March 1994. (Greg Marinovich)

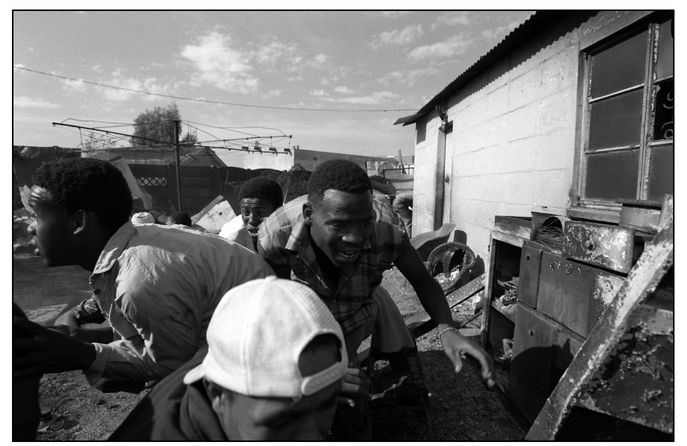

A young boy races past the words ‘No Peace’ in the

dead zone near Thokoza’s Khumalo Street, shortly before South

Africa’s first non-racial election in April 1994. (Joao

Silva)

ANC self-defence-unit members duck gunfire during

a clash with Inkatha militants from the hostels and houses of

‘Ulundi’ in the dead zone near Khumalo Street. (Joao Silva)

ANC fighters carry a wounded comrade, spouting

blood from his side, during an attack on the Inkatha stronghold of

Mshay’zafe Hostel in Thokoza on 19 April, 1994 - the day after Ken

Oosterbroek was killed in the same area. (Joao Silva)

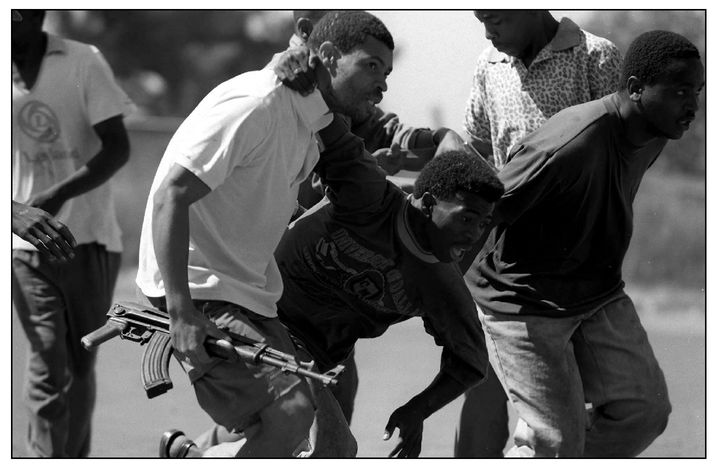

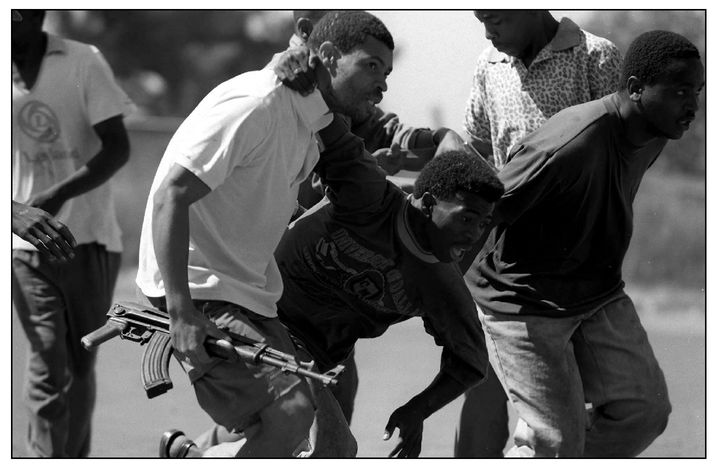

ANC fighters with an AK-47 carry a wounded comrade

during an attack on the Inkatha stronghold of Mshay’zafe Hostel in

Thokoza. (Joao Silva)

A wounded Greg Marinovich is assisted by James

Nachtwey, while Joao Silva takes pictures of Gary Bernard and an

officer from the National Peacekeeping Force as they carry the

fatally wounded Ken Oosterbroek in the background, 18 April 1994,

Thokoza. (Juda Ngwenya / Reuters)

An officer with the National Peacekeeping Force

assists Gary Bernard with a fatally wounded Ken Oosterbroek. (Joao

Silva)

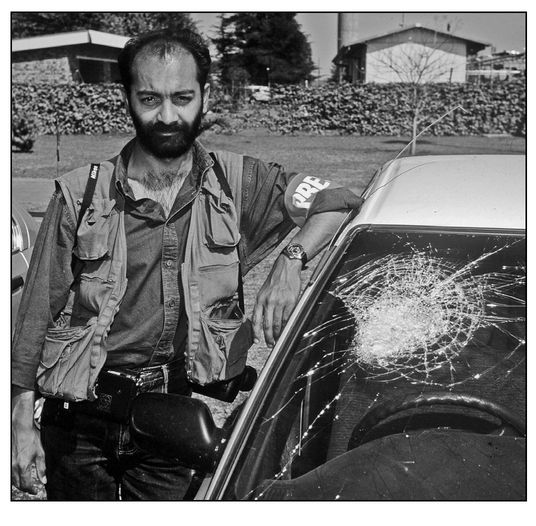

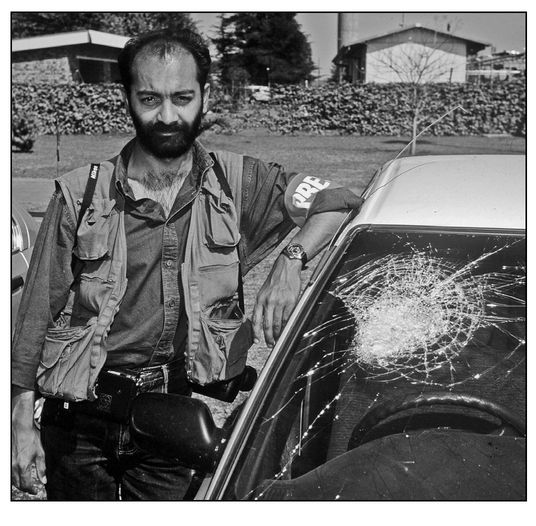

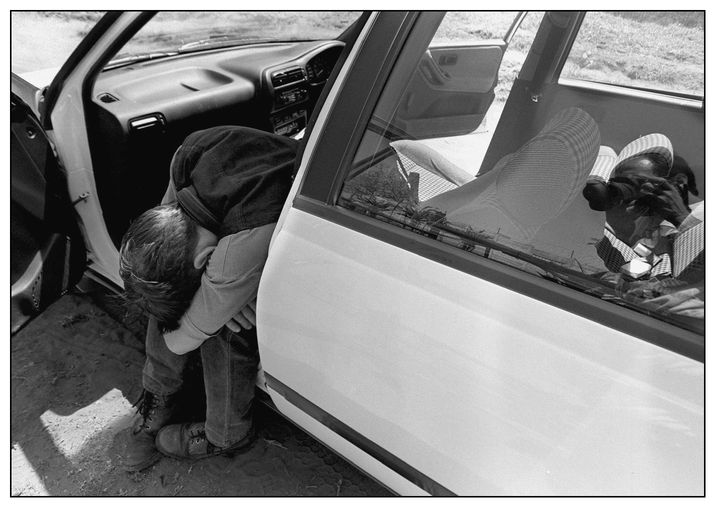

Abdul Shariff, photographed in 1993 next to his

car, which was damaged during township clashes. Abdul was killed in

cross-fire between ANC and Inkatha militants in Kathlehong township

on 9 January, 1994. (Kevin Carter)

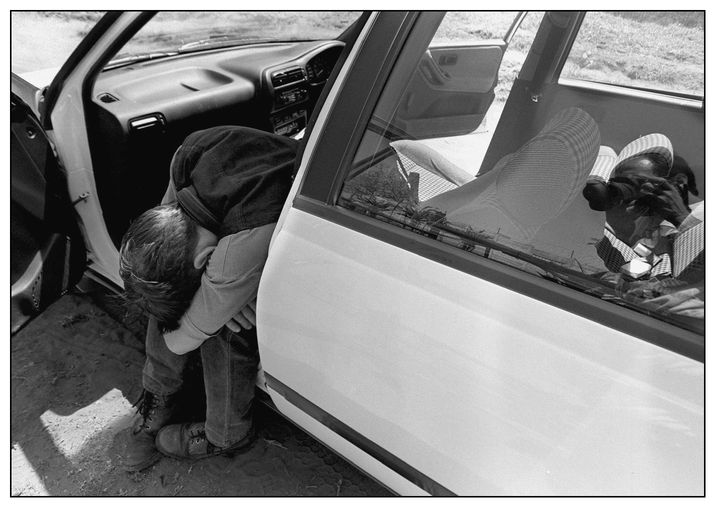

An exhausted Gary Bernard during a break from

covering violence after South Africa’s first democratic election in

1994. (Joao Silva)

Left:

A Serb woman lies dead in the snow just hours

after she was given protection by Croat soldiers during an

offensive on 26 December, 1991 after Croat forces retook parts of

the Papuk mountains - traditionally an ethnically mixed area. Some

Croatian units were trying to protect civilians (as in the case of

this woman) but others were intent on killing them. (Greg

Marinovich)

Below:

An Afghan man carries his fatally wounded son into

the hospital in Kabul after an artillery attack on their

residential neighbourhood, 1994. (Joao Silva)

Right:

A Somali woman weeps as her child dies in her arms

at an NGO centre in the town of Baidoa where thousands died of a

war-induced famine in 1992. (Joao Silva)

Below:

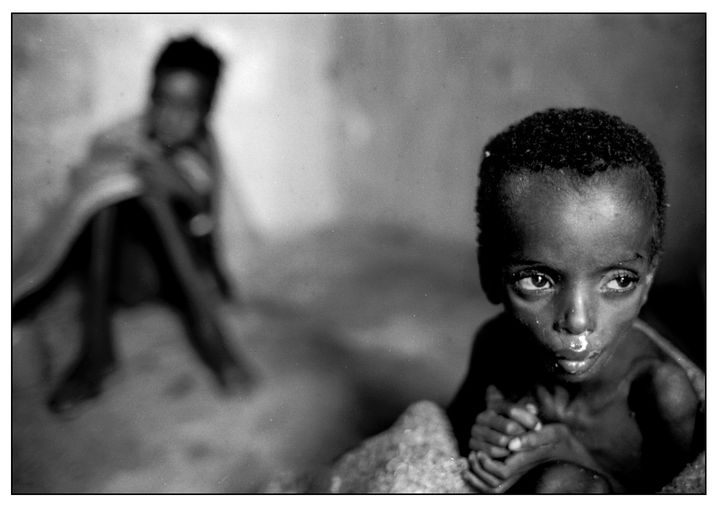

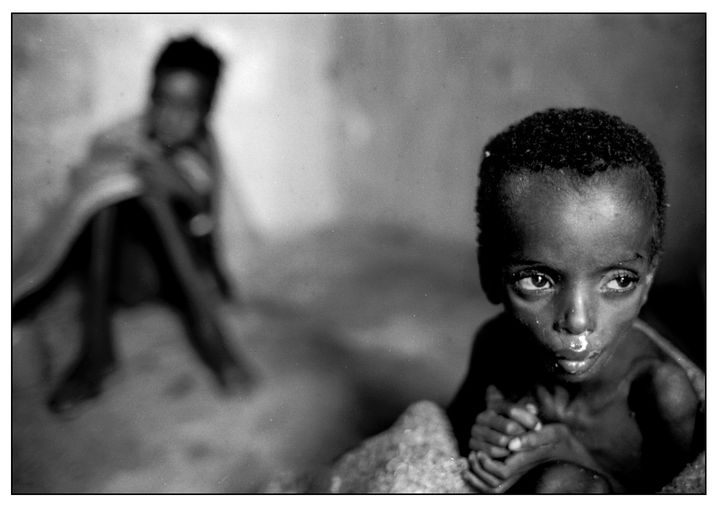

A starving and ill Somali child waits to die in an

NGO centre in Baidoa. This room was for children who were too far

gone for the aid workers to waste precious food and medicines on

them. (Greg Marinovich)

A colleague reaches to assist Greg Marinovich,

wounded by police during confrontations between police and

‘coloured’ residents of Westbury, Johannesburg, who were protesting

alleged discrimination by the newly elected majority black

government, September 1994. (Joao Silva)

Greg Marinovich being assisted to a South African

armoured vehicle after being shot in Lesotho, September 1998, when

the South African forces went in to quell a coup, and met stiff

resistance from BaSotho troops. (Joao Silva)

After two further operations I was finally able to

move out of intensive care. The crisis to survive was over and I

began to fret about missing the most important story of my life:

Inkatha’s final inclusion in the electoral process, which required

the last-minute application of stickers bearing the beaming face of

Inkatha’s leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the Inkatha symbol on to

the bottom of the lengthy ballot papers, a reminder of how close we

had been to civil war. Inkatha’s participation had at length been

secured by means of gerrymandering in their Zulu heartland, which

would ensure them a majority there. It was a small price to pay to

avert disaster, but the deal did not please those right-wing whites

and security force elements who had thought that they could use

Inkatha as part of their strategy to preserve white power. Every

day, explosions reverberated through the Reef cities, a last

attempt by the right-wing to derail the elections.

Every afternoon and evening my ward was a meeting

place for dozens of photographers, journalists and friends. People

started bringing food. When Joao and the others came to visit after

a day in the townships, they would always find a crowd already

there. It was like a subdued party to celebrate that we were still

alive and to forget the sad times which surrounded us, if only for

a while. Late one night I was already asleep when Ingrid Formaneck

and Cynde Strand from CNN crept in, wearing blonde big-hair wigs.

Soon we were giggling and laughing, and the night-sister, having

taken one look at us, retreated without a word to her

station.

One day Kevin visited. His face was mobile and his

eyes would not meet mine for more than an instant. ‘I’ve got your

cameras - I’ve borrowed them.’ I said fine, but I was surprised. I

could not understand why he was acting so strangely - our

friendship was such that he knew that I would have lent him the

equipment without hesitation, as he would have lent me whatever I

needed. Perhaps he had been in a rush when he told me, but he must

have known how upset I was at not being able to shoot the elections

I had waited so many years for - what it meant to me to be stuck in

hospital while everyone else was out

shooting pictures. And here he was, taking the cameras I should

have been using, without even a word of consideration. It was

unusually insensitive of Kevin. I was also puzzled by the fact that

he did not visit me as often as the others. Deep down, I had the

feeling Kevin was avoiding me, but I couldn’t understand why.

In that period Kevin was confused and angry. In the

space of just two weeks, he had been arrested for drunken driving,

kicked out by his girlfriend, lost his job, won a Pulitzer, been

reinstated in his job, only to have his best friend killed. Kevin -

and the rest of us - were convinced that Reuters had only rehired

him because of the Pulitzer. This was not Reuters’ version of

events, but Kevin was deeply angry with them and the relationship

was clearly poisoned. I suggested he try the AP and they readily

agreed to take his pictures, even though his name was at that time

associated with Reuters - the wire constantly needed to be fed

pictures. So, just a few days before the election, Kevin resigned

from Reuters, and did a couple of freelance jobs for the AP, but

then Mikey got him a more regular gig with the French wire service

Agence France Presse, and so it was for AFP that he covered the

election.

But Kevin was struggling with more than just

employment. I heard that he had started saying, ‘It should have

been me instead of Ken who took the bullet,’ though he never said

anything of the kind to me. In front of me, he seemed to be the

least affected by Ken’s death, which was strange, as I knew that

Kevin loved Ken like a twin brother. I knew too that he was a

dramatic person, capable of intense emotion and of showing

it.

I later understood Kevin’s distancing himself from

me as a strange form of envy. To have suffered Ken’s fate would

have been Kevin’s first choice. Apparently, Kevin constantly talked

about getting killed during that time - he did not want to be shot

and wounded; he wanted to be killed. He wanted to take the bullet

that had killed his best friend. He resented me as I had won second

prize. I was there and I took the second bullet, but had survived,

so I had a special bond with Ken that nobody else could

match.

27 April 1994: Election Day

Before the shooting, I had been planning to spend

election day with the Rapoo family. For me, that family was a

symbol of courageous people overcoming what had befallen them. They

had suffered greatly under the oppressive apartheid system and I

wanted to share with them the moment when they voted. But I was in

hospital, missing out on what generations of South Africans had

been waiting, fighting and even dying for - the first non-racial,

fully democratic election. I suggested to Joao that it might be a

good idea if he spent the morning with the Rapoo family - the

pictures could be really good, at least as good as anywhere else.

He immediately understood that I wanted him to be my substitute. I

was not sure if he thought it was a good idea for pictures, or if

he was doing it for me, knowing how much I wanted to be with the

Rapoos. ‘But what if shit goes down?’ he asked, referring to the

possibility of violence, thinking about Thokoza. ‘It could go down

anywhere,’ I replied, rather disingenuously. He and Gary agreed to

go to Soweto for the first day of voting, while Kevin, Jim and the

rest decided to go to Thokoza, where the potential for conflict was

the highest. But, other than the right-wing bombing campaign, which

continued in an attempt to disrupt the election, the level of

violence had dropped right off - it had ceased the day after Ken

was killed, when Buthelezi had cynically announced that Inkatha

would, after all, participate in the election. Responding to the

announcement in a press conference, Mandela had said that he hoped

Ken would be the last person to die.

Joao and Gary arrived in Meadowlands, Soweto, at

dawn, and then joined the Rapoos in their bus as they went to

collect people from old age homes. Tarzan had planned to paint the

vintage bus that they used to transport fellow church members to

services in bright colours for election day, but its notorious

gearbox had kept him busy most of the previous week and so they had

to collect the pensioners with the bus in its drab sand-coloured

paint. These were people who, as youngsters, had experienced the

beginning of apartheid and had lived all their adult lives under

its shadow - but they had now lived long enough to vote for its

demise.

The day had begun hours earlier for the Rapoos. The

old man, Boytjie, had had a restless night and got out of bed at

four to make himself a pot of tea. While the water was boiling, he

heard noises from the street. He went out into the yard and looked

through the iron gates. A group of old men in coats were standing

in the street. ‘What’s wrong?’ he called, worried that something

had happened, that there had again been violence. ‘Nothing’s wrong.

We’ve come to queue,’ they told him. The school in the Rapoos’

street was one of the designated polling-stations.

Boytjie invited them in for tea. For all of the

old-timers, it was the dawn of the restoration of their civil

rights which had been so unequivocally removed by volumes of

discriminatory legislation. Thirtynine years before, the police had

forcibly moved thousands of these urbanites to the empty veld that

would become a part of sprawling Soweto. The matchbox house they

were allocated had at first been the symbol of their loss of

personal freedom, but in that house, at 1096a Bakwena Street, the

cycles of life and death had permeated the very bricks of the

house, making it a home. It was in that tiny kitchen, where his

family had cooked thousands of meals, that Boytjie had been doused

in petrol and awaited a fiery death as he helplessly watched his

son Stanley being taken away for execution by hostel Zulus. It was

in that kitchen that he had heard the news of his grandson

Johannes’s death at the hands of the police. There were many

memories to occupy Boytjie and his friends while they silently

drank tea. As the break of day approached, the old men put on their

heavy woollen coats and joined the lengthening line outside the

primary school. The old folk wanted to vote quickly, just in case

something happened to upset the miracle.

Tarzan was the next to rouse himself that chilly

morning. It was barely five o’clock, but when he went to open the

yard he saw a line of people stretching around the block. He rushed

back in and shook his wife by the shoulder, ‘Maki, wake up, wake

up! You said that since we were next to the school, we’d be first

to vote. Have you seen the queue outside?’

This was the day on which decades of disempowerment

would fall

away as people made their mark on the ballot - they could finally

choose who would govern them. The four years of pain and sacrifice

they had experienced living in one of the dead zones - ever since

the unbanning of the ANC - had made them even more determined to

vote for Nelson Mandela and the ANC. They had watched former State

President F.W. de Klerk tour Soweto as his National Party attempted

to buy black votes in a frantic campaign circus. But few could

forget a half-century of the National Party’s apartheid for a free

T-shirt and a boerewors roll.

The whole family queued to vote together, led by

Boytjie. The identity documents that had for so long been their

burden were now their passport to vote. When it was Maki’s turn to

enter the curtained booth and make her choice, she told me later,

her heart beat faster: ‘It was as if something has been lifted off

my shoulders. I felt as if there was something magical about it; as

if God had made the school holy for everybody who was going in. I

felt happy that at long last we were asked to participate in who

must govern the country.’

Maki and other neighbourhood women had prepared

food and drinks for the voters. The morning had started out cold,

but by ten o’clock the sun was hot and the old folk were feeling

faint from the heat. Maki was concerned that the older people would

collapse from the hours of waiting. But there were so many people

that the neighbourhood women could only give each a plate of mielie

meal porridge, soup made from bones, a bread roll and a glass of

orange juice mixed in a bucket. When the ANC activists saw what the

women were doing, they rushed out and bought barrels of take-away

chicken for everybody in the queue.

Maki continued preparing and handing out food until

dusk and then went with Tarzan to the church for a special service.

There were far fewer people attending than was usual, but for Maki

‘The service was also magical. Everybody felt as if Nelson Mandela

has given us the land of milk and honey, we had that feeling. Even

the sermon spoke of that - the vote had come, we had been led to

the land of milk and honey.’

The vote had come ten days after the shooting in

Thokoza and I had

recovered enough to be able to cast my vote in the polling-booth

at the hospital. As I approached the rather incongruously simple

tin ballotbox, I felt elated. The AP had lent me a point-and-shoot

camera. I shot pictures of my plaster-cast hand pushing the

ballot-paper into the box. I was hoping the AP would put a picture

out on the wire, because like a naughty schoolboy I had written,

‘Fuck the Nats (National Party)’ on the plaster. The AP had better

pictures to move that day and my little dig went unnoticed. They

had given me the camera because they knew how strongly I felt about

missing out on photographing the election. And they were right, the

chance to vote and to shoot some pictures had lifted me out of my

depression, if only for a few hours.

Kevin was at a voting-station in the extremely

affluent northern suburbs where white home-owners voted alongside

their maids and gardeners. Kevin wanted to vote too, but he had

forgotten his identity book. He argued and tried to cajole the

officials into letting him vote anyway, but they refused. Kevin

became angry, abusive, running his hands through his hair in

frustration. I never did find out where Kevin eventually voted, but

he must have done so - for there was still the next day in which to

vote.

The second day of voting was quieter, and Joao,

Gary and Brauchli spent it in Thokoza. They eventually ran out of

fresh scenes to shoot and they just hung out as the lines dwindled

and polling-stations closed. Dusk was approaching and they idly

played Frisbee. Being in Khumalo Street, near the spot where Ken

had died, made them sullen. The excitement of that historic vote

had been much reduced by Ken’s death. Joao could not find the

emotion he wanted to feel while photographing. While they were

idling at the garage, it suddenly struck Brauchli that the South

Africans, Joao and Gary, had photographed hundreds of votes being

cast, but had themselves not yet voted. It was late on the final

day and the first polling-booth they went to in Thokoza was already

shut. They wanted to vote in the township, felt that it was right.

They eventually found one that was still open. It was a school in

the southern part of Kathlehong, where the ANC fighter Distance had

told us that he was glad that Abdul had been killed. That had been

just

three months before, but so much had happened since that it felt

like years. Brauchli thought it a great moment, watching his

friends cast their votes: he clowned with the women and made the

boys laugh for the camera, but when Joao entered the cubicle to

make his mark on the ballot-paper, he stopped smiling. His thoughts

turned to Ken and me. ‘I was in so much pain that I did not savour

the moment when I voted for Nelson Mandela.’

For Joao, the period following Ken’s death was dark

and blurred. He worked like a machine, up at dawn to go into the

townships and shoot pictures, and then come to visit me in

hospital. He would invariably drink heavily before going home to

sleep and start the cycle again the next morning. For Viv, it was a

miserable period: Joao was aggressive and in pain, but he would not

share it with her. It was as if he could only relate that pain to

colleagues who had been in the townships. He felt that Viv should

be shielded from the details. Viv had grown used to being excluded

from what Joao experienced, but now, instead of home being a

refuge, it had become a part of Joao’s hurt-filled world. He didn’t

laugh any more. The weeks dragged on, in what seemed like one long,

cheerless day. For the first time in their seven years together,

she contemplated leaving him.

10 May 1994

Nelson Mandela was sworn in as president behind

bullet-proof glass because a right-wing assassination plot had been

uncovered. But despite that, hundreds of thousands of people

gathered on the lawns of the Union Buildings in Pretoria to cherish

the moment. After decades of apartheid, and several hundred years

of racial discrimination, South Africa finally had a democratically

elected government. Kevin was there somewhere, and the others were

spread out at different celebrations. I was out of hospital, back

home and well enough to feel thwarted at not being able to

participate in the day. My joy at watching Mandela dance his little

jig to the roar of the huge crowd gave way to weeping and

depression. I was worn out, thinking about Ken a lot of the time.

Waves of self-pity swept over me - when would I be able to work

again? The

AP had offered me a desk-job while I recovered. I had refused, but

was touched that they were treating me like family. They had also

offered to pick up my large hospital tab, but Newsweek had

paid for that and the Newsweek photo director had promised

me a contract - unlike doing piecemeal freelance work for them, a

contract is one of the most lucrative and prestigious gigs in the

business. Once I was back on my feet, things were going to be

good.

Joao and Gary came round to visit me after

photographing streetcelebrations. They told me that the townships

were just one big party, everyone having a great time. I insisted

we go to a party and they took me to Soweto. Balloons were strung

low across the section of the street that had been closed off.

People who had television sets had brought them out into their

yards so their neighbours could also watch. Others had gathered

around braais, barbecuing meat, and people were coming up and

forcing drinks on us. Everyone wanted their picture taken. After a

while we left that drunken street bash and went to visit the

Rapoos. I was happy that at least I had experienced a little of the

euphoria.