5

BANG-BANG

I lament with sorrow and cry because the boys

are finished. The boys are finished

Traditional Acholi funeral song

We were all white, middle-class young men, but we

went to those unfamiliar black townships for widely differing

reasons and with contrasting approaches; over the years, we would

find common ground in our shared experiences and develop

friendships.

Ken, unlike the rest of us, was not at ease with

black people, and in the beginning I avoided working with him too

much because of that. Not that I can recall Ken ever saying

anything racist: it was just a difference in response, in empathy.

Perhaps he was as uncomfortable with me and my open support for

blacks in a country where identity was deeply, indelibly based on

the colour of a man’s skin and how tight his hair curled. But Ken’s

experiences as a photographer slowly changed his attitudes and had

rid him of that native, unthinking racism.

While Ken was undergoing that process, Joao and he

became close friends. The hours spent processing and printing

pictures in each other’s company created a lot of time to learn

about each other. They mostly just chatted or gossiped, but the

claustrophobic processing cubbyholes at The Star were ideal

for intimacies and sharing secrets. It was in Ken’s

cubicle that he showed Joao the contents of a photo-paper box he

treasured. Inside were pictures of a little girl: Tabitha, his

daughter from a previous relationship. Ken’s wife, Monica, had

forbidden him to see his daughter and had even made him promise in

writing to not visit the child. For someone who worked so hard to

keep things in hand, there were parts of Ken’s life that were

definitely out of control. Monica’s jealousy was so intense that

Ken would ask Joao and others at the newspaper to lie to her when

he went to see Tabitha. Ken hid those pictures, fearing Monica

would destroy them if she ever found them.

On Joao’s birthday in 1992, he was in his darkroom

cubicle processing film when Ken came in to see how the job had

gone. After some time, grinning broadly, Ken handed him a large

brown envelope. Joao opened it, expecting a card, but instead it

was a black-and-white photograph of a train smash and written on

the bottom of the picture was ‘Happy birthday Joao!!’ Joao wondered

why Ken had given him that picture. ‘That’s what happened the day

you were born!’ Ken explained. He had gone to the newspaper

archives to see what had been on the front page on 9 August 1966,

unearthed the original negative and made an 8’ by 10’ print. ‘A lot

of people die?’ Joao asked. ‘Lots,’ replied Ken, who had been born

on Valentine’s Day. ‘On my birthday, they had some girl with

flowers; on yours there has to be a disaster!’

By 1992, Ken had turned The Star’s photo

department around. That year Joao won the national Press

Photographer’s award, Ken was runner-up and The Star

photographers dominated all the categories. It was through Joao

that I got to know Ken better. There were individual friendships

between the four of us, as well as a growing common bond. Our

girlfriends and wives became friends, and we would get together for

meals and to discuss and edit the pictures when one of us had done

a big story.

When there was a lot of violence, we would team up

for ‘dawn patrols’ - waking before dawn to be in the townships by

first light. It was a ritual that we had each done singly at first

and then later two or three of us would sometimes cruise together.

The companionship meant I did not feel so alone when the alarm

jerked me awake to face

the next day of witnessing the violence. Sometimes when the days

had been really bad I would wake seconds before the alarm and try

to find excuses for staying in that warm bed, but the thought that

the others were waiting somewhere would help me to get up.

A girl leads her younger sister to safety as an

impi, or regiment, of Inkatha-supporting Zulu warriors moves down

Khumalo Street, Thokoza, at the start of the Hostel War, August

1990. Ken would later be killed in this same street, four years

later. (Ken Oosterbroek / The Star)

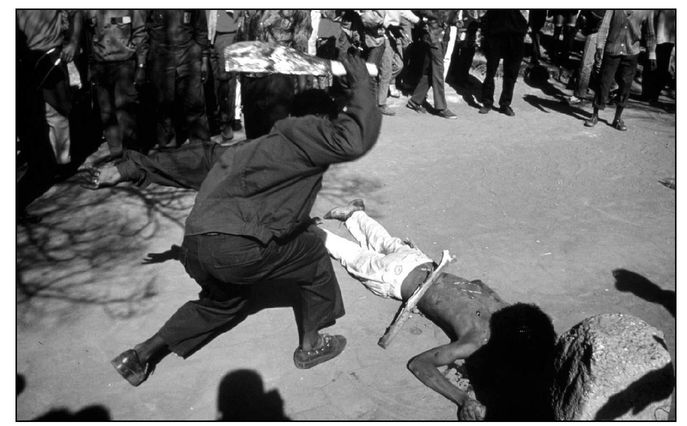

Nancefield Hostel, Soweto, 17 August, 1990. A

group of Inkatha-supporting Zulu hostel dwellers kill a man they

suspect of being a Xhosa - understood by the attackers to be

synonymous with the ANC. It turned out that he was an ethnic Pondo

of undetermined political allegiance. (Greg Marinovich)

Khumalo Street, Thokoza, December 1990. A man

laughs towards the camera as he passes a group of female Inkatha

supporters beating an unidentified woman. The severely injured

woman was later picked up by police, but it is not known if she

survived. (Joao Silva)

ANC-supporting Xhosa warriors receive magic potion

or intelezi from a sangoma at ‘the mountain’ in

Bekkersdal township, west of Johannesburg, 1993. (Kevin

Carter/Corbis Sygma)

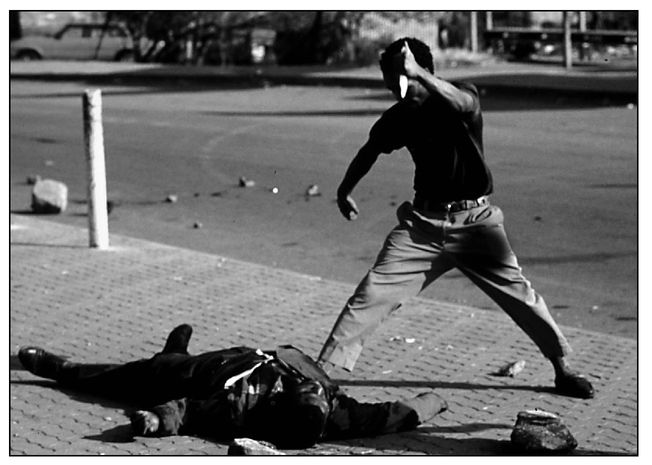

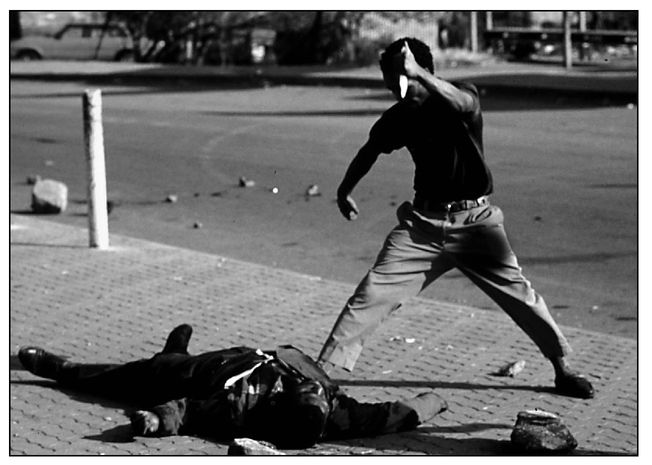

Inhlazane, Soweto, 15 September, 1990. An ANC

supporter prepares to plunge a knife into Lindsaye Tshabalala, a

suspected Inkatha supporter, during clashes at the start of the

Hostel War. (Greg Marinovich)

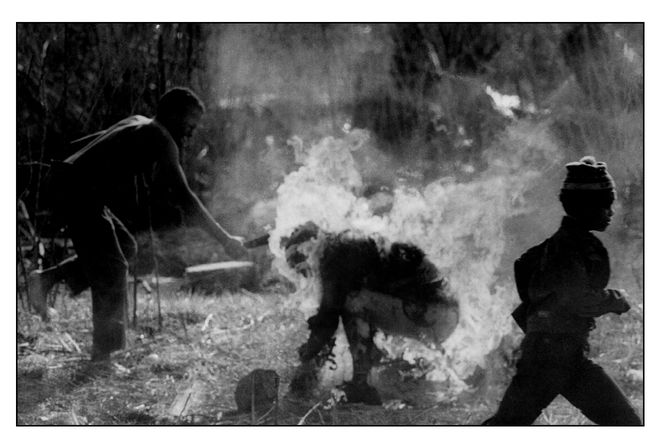

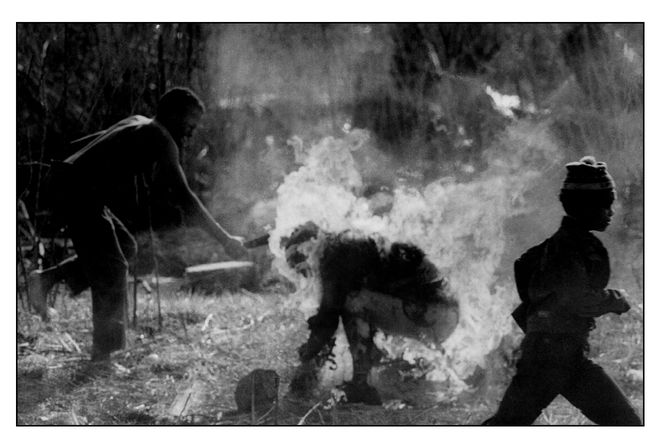

Inhlazane, Soweto, 15 September, 1990. An ANC

supporter hacks at a burning Lindsaye Tshabalala as a young boy

flees. This was one of a series of pictures that won the Pulitzer

Prize for Spot News in 1990. (Greg Marinovich)

Maki and Sandy ‘Tarzan’ Rapoo explain how their

nephew, Johannes, was shot dead by police in their Meadowlands Zone

1 suburb of Soweto, June 1992. They were in the kitchen of the

house on Bakwena Street, where they had previously suffered the

loss of Sandy’s younger brother, Stanley. (Greg Marinovich)

Maki Rapoo leads her brother-in-law, Lucas, out

into the yard of the family home on Bakwena Street to do a

traditional dance during his wedding reception in 1996. (Greg

Marinovich)

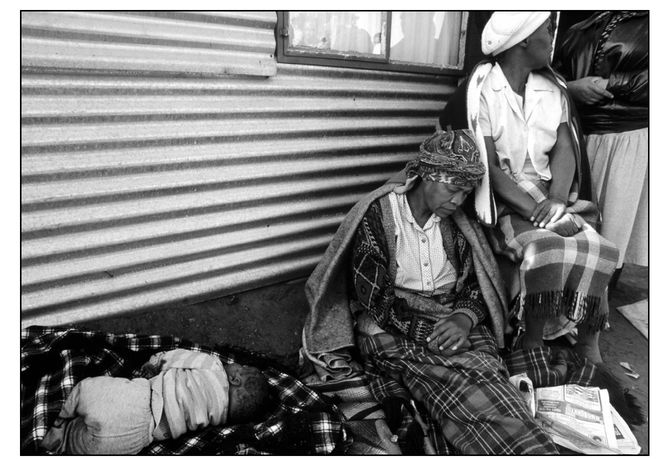

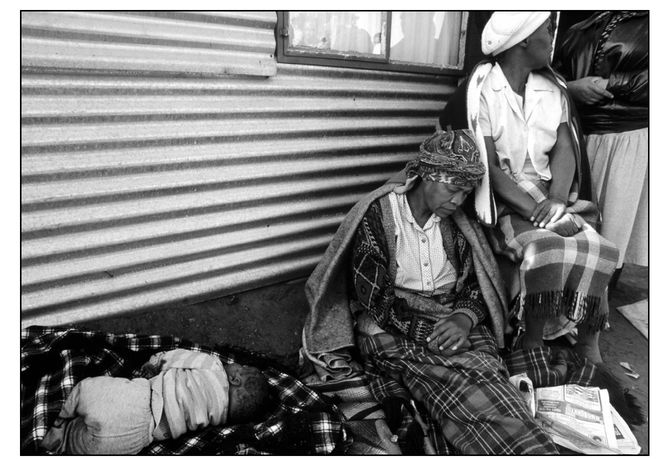

The maternal aunt of Aaron Mathope grieves next to

the nine-month-old infant’s corpse after he was hacked to death by

Inkatha attackers, aided by police, in Boipatong Township, 18 June,

1992. 45 people were killed. One of the Inkatha attackers’ leaders

later explained the killing of Aaron thus: ‘You must remember that

a snake gives birth to a snake.’ (Greg Marinovich)

Policemen open fire on an unarmed crowd of

Boipatong residents who had wanted access to a man shot dead

earlier by police after President FW de Klerk was chased from the

township on 20 June, 1992, days after the massacre. There were

several deaths and injuries. Police and the government denied this

incident occurred, saying residents and journalists had fabricated

the casualties. (Greg Marinovich)

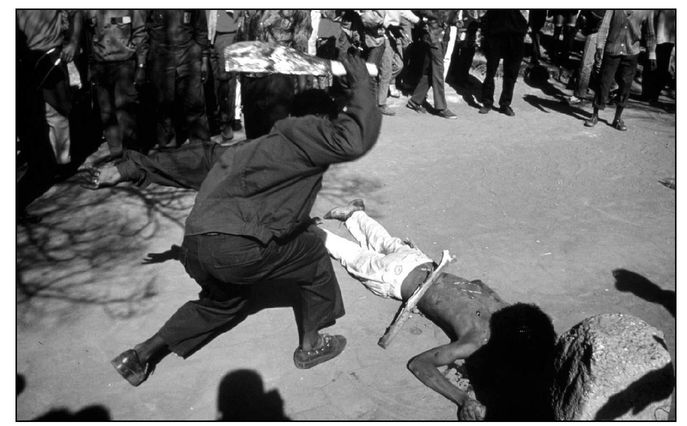

A resident of Boipatong hacks at the body of a

Zulu man suspected of being an Inkatha member who had taken part in

the Boipatong Massacre. He was later burned. (Joao Silva)

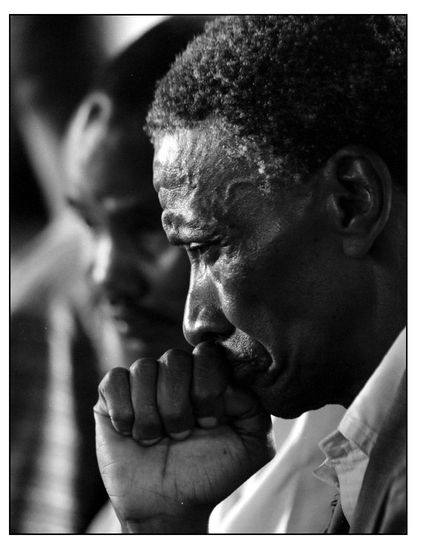

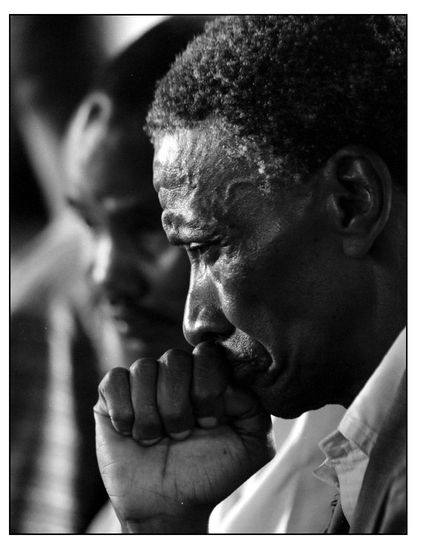

Daniel Sebolai, 64, who lost his wife and son in

the Boipatong Massacre, holds back the tears during a workshop on

issues related to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission in

Sebokeng, 28 October, 1998. Next to him is Boy Samuel Makgome, 48,

who lost his eye during an attack on a train by Inkatha Freedom

Party members in 1992. Hundreds of victims who did not find

sufficient or any redress from the commission are counselled and

advised of their rights by nongovernmental self-help groups made up

of human-rights victims. (Greg Marinovich)

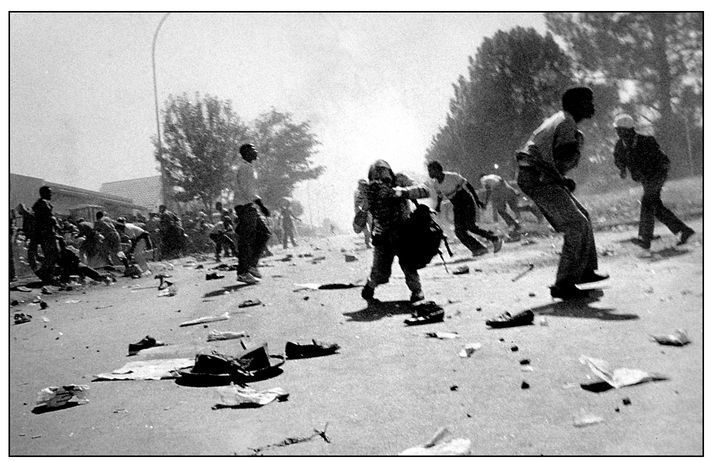

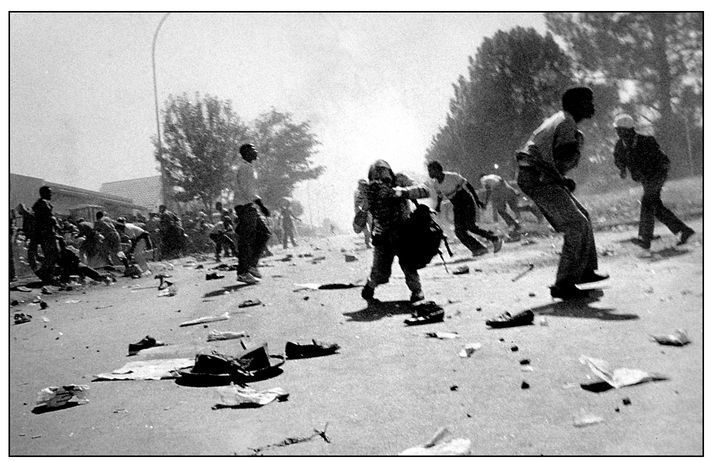

An ANC mourner takes evasive action from police

gunfire during violent clashes at the funeral of Communist Party

and ANC military leader, Chris Hani, 19 April, 1993. Hani was

assassinated by white extremists. An election date for one year

later was set soon afterwards. (Greg Marinovich)

Kevin Carter aims his camera to take a picture of

Ken Oosterbroek as Soweto residents flee police gunfire outside the

Protea police station where they had been protesting after Chris

Hani was assassinated by right-wing whites, April 1993. (Ken

Oosterbroek / The Star)

From 1991 to 1993, South African political players

were embroiled in protracted negotiations towards a transition to

the ‘New South Africa’, and the ongoing violence was being used as

a negotiating tool. It was impossible not to notice how the number

of inexplicable massacres and attacks surged whenever the talks

were at a critical stage. Even though we each in our own way were

deeply motivated by the story, pictures and politics, cash also had

its part in getting us up before the sun. The dawn was the

transition between the chaos of the night and the occasional order

of day - when the police would come in to collect the bodies.

I had become known as a conflict photographer. I

could ask for assignments to almost any place, as long as people

were killing each other. But it had taken me a while to learn how

to make use of that reputation. When I had gone to New York in

August of 1991 to collect the Pulitzer, I had asked if I had to

wear a tux to the ceremony, not knowing that tuxes are not worn to

lunchtime affairs. I also naïvely thought that the award would be a

great opportunity to say something about what was happening back

home. I spent days working on a speech and it was in my jacket

pocket when my name was called and I walked up to the dias at

Columbia University. But all the man did was shake my hand and give

me a little crystal paperweight with Mr Pulitzer’s image engraved

on it before ushering me away.

The other winners received their awards with equal

haste and then there was a luncheon. It was the 75th anniversary of

the prize and all living winners had been invited. It was an

absurdly ideal place to establish contacts with many of the most

important picture editors and the world’s greatest photographers. I

made a wan effort to meet people, but I was in no frame of mind to

do it effectively and left soon afterwards.

Despite my ineptitude in handling the business side

of photography

and in marketing myself, by late September of 1991 I had convinced

the AP to assign me to cover the war in Croatia, and within days I

was in the front-line village of Nustar. It was autumn, cold and

wet, and the roads had been churned into muddy trails by the tanks.

It was my first time in a ‘real war’ with tanks, artillery and

machine-guns. I had no clue of what was reasonably safe and what

was insane, yet somehow I survived those first weeks without

getting myself or anyone else killed. I found that I liked war.

There was a peculiar, liberating excitement in taking cover from an

artillery barrage in a woodshed that offered no protection at all.

Two other journalists shared that particular woodshed with me: one

was a young British photographer called Paul Jenks, who huddled in

a steel wheelbarrow because it made him feel safer as the massive

detonation of nearby shells mingled with the scream of others

passing overhead. He would be killed months later by a Croat

sniper’s bullet: Paul had come too close to discovering the cause

of the death of another journalist who had been strangled by a

member of a motley unit of international volunteers to the Croat

army. My other companion was Heidi Rinke, an Austrian journalist

with long black hair, beautiful green eyes and a wicked sense of

humour. I lent her my flak jacket as she did not have one and so

began a romance that would keep us warm through the long winter

months of covering the Serbo-Croat war.

Because of my Croat parentage, I spoke a passable

pidgin Serbo-Croat and this sometimes gained me good access. So, in

December of 1991, Heidi and I were the only journalists

accompanying a troop of Croatian soldiers as they took village

after village in the Papuk mountains. The Croats met only token

resistance from geriatric villagers firing old hunting rifles at

them, since the Yugoslav army and the Serb militia had already

retreated, having seemingly decided that the area was bound to be

lost sooner or later. It was eerie to see house after house burst

into flames as we advanced on foot. In addition to putting Serb

homes to the torch, many of the Croat soldiers were looting

everything they could find, especially the local plum moonshine,

slivovic. They also murdered many of the old folk who had been left

behind. Deeper in the mountains, a soldier and I helped an old lady

to the safety of her

neighbour’s farmhouse after her house had been torched. The Croat

commander, a decent enough man in charge of a bunch of murderous

drunks, promised that the women would be safe. A few hours later, I

stopped by to check on them, but the barn and house had been burnt

out. My heart was in my mouth as I searched for the two women. I

found only one and she was lying dead in the frozen mud.

In another hamlet, on another day, a

conscience-stricken Croat soldier whispered to me that there was an

old man still alive in one of the partially burnt farmhouses. Heidi

and I tried to be nonchalant as we walked up the drive where blood

spilled on the mud gave urgency to our search. We found nothing in

the house, not even a corpse. I came back down to the road and

surreptitiously asked the soldier where the wounded man was; he was

terrified that his comrades would see him talking to me and

whispered, ‘In the barn.’ I went back up past the blood and to the

wooden barn, but saw only piles of hay. I started pulling at it,

prepared for the worst; but I still got a fright when confronted by

the grey, bloodless and unshaven face of an old man at the bottom

of the pile. He was alive, but in a bad way. He had been shot and

left under the hay to die. I tried to tell him to be calm, that we

would get help. While Heidi was staunching the old peasant’s

bleeding leg, I bent closer to hear what he was saying. I had my

ear next to his mouth before I understood what it was that he kept

repeating: ‘Don’t let the pigs eat my feet, don’t let the pigs eat

my feet!’ It was not a crazy fear - pigs will eat anything, and on

a few occasions I had seen pigs feeding off human corpses.

It was a strange war. One day I discovered a

white-haired Serb lying dead in a ditch with his ears cut off. An

unshaven, grinning Croat soldier with rotten teeth came up to me as

I was taking pictures and he gleefully told me that he had killed

and mutilated the old villager. His commander had a standing offer

that anyone who brought him a pair of Serb ears could go home for

four days. My Croatian surname allowed me to witness one side of

the intimate brutalities of the civil war, but it precluded me from

seeing the even greater toll of Serb atrocities up close.

Despite the horrors and my ancestral links to the

country, the war did not have the same emotional impact on me as

the events I had witnessed in South Africa - it was not my country

and not my struggle. I was definitely there as a foreign

journalist. In February of 1992, I returned to South Africa with

Heidi. We lived together in the house I’d bought shortly after

winning the Pulitzer. I had taken out a mortgage in order to buy

it, as for the first time in my life I felt financially secure,

after years of living hand-to-mouth. I was perpetually amazed by

the turnaround in my circumstances - just one year previously I had

been on the run from the police, but I now reckoned that there

would be an outcry if they arrested South Africa’s only Pulitzer

Prize-winner. I began to use my real name as a by-line. But in

reality, the environment was changing, and ‘crimes’ such as mine

were being ignored, as were draft-dodgers and conscientious

objectors - whereas they had previously been hunted to ensure there

was no ‘moral rot’ among whites. But even the Pulitzer could not

change the effect that witnessing such searing events had had on

me; on my return I found that I was almost immediately emotionally

and politically ensnared by the events in South Africa. Unlike in

the former Yugoslavia, I could not keep a distance from this story,

nor from the people I photographed.

I remember a Sunday morning just weeks after coming

back. In the street outside my house I was cleaning my car. Several

neighbours also had hosepipes and buckets out as they cleaned and

polished their cars - a Sunday ritual in my working-class

neighbourhood. We greeted each other - they recognized me from

interviews on television and in the papers. What they did not know

was that I was not getting the car spruced up for the weekend, but

that I was grimly trying to wash someone’s brains out of the cloth

upholstery of my back seat. The previous afternoon, while most of

South Africa was grilling meat on the braai or watching sport on

television, I had been racing through the streets of Soweto trying

to get to the hospital before the rasping, noisy breathing of the

young man lying on my back seat ceased. The comrade’s girlfriend

cradled his head in her lap and Heidi, sitting alongside, was

telling me not to bother speeding, that it would make no

difference. Brain-matter and fluid bubbled freely out of a gunshot

wound in his head and he was not going to make it. At the hospital

they pronounced him dead.

So, despite the cheery greetings from my

neighbours, I resented them cleaning simple street dirt off their

cars. This was something that I could not explain to them, nor to

anyone else. It was as if they were occupying a different planet to

me. It was precisely this that helped draw Joao, Ken, Kevin and me

close to each other. When we tried to discuss those little telling

details from incidents in the townships with people who had never

experienced them, the usual response was either disgust or

uncomprehending stares. We could only really talk about these

matters to each other. Kevin had once written about his feelings on

photography and covering conflict in an article which expressed

thoughts that we had all, on occasion, shared: ‘I suffer depression

from what I see and experience nightmares. I feel alienated from

“normal” people, including my family. I find myself unable to

relate to or engage in frivolous conversation. The shutters come

down and I recede into a dark place with dark images of blood and

death in godforsaken dusty places.’

It was from this sense of being outsiders from the

society we had grown up in, and of being insiders to an arcane

world, that we developed into a circle of friends prompting a local

lifestyle magazine, Living, to dub some of us ‘the Bang-Bang

Paparazzi’ in a 1992 article. Joao and I were so offended by the

word ‘paparazzi’ that we persuaded the editor of the magazine-a

friend called Chris Marais - to change it to ‘the Bang-Bang Club’

when he wrote a follow-up piece that was about the four of us. We

were a little embarrassed by the name and its implications, but we

did appreciate being acknowledged for what we were doing. No matter

what they called us, we liked the credit.

Articles like the Bang-Bang Club piece made us

minor celebrities in media circles. As a result, several young

South African photographers were motivated to try their hand at

documenting the violence. One of these was a young man called Gary

Bernard, who had always wanted to be a professional

news-photographer. He kept seeing our pictures in the

papers and he eventually signed up at a non-profit photographic

workshop, where he attended classes in the evening while working as

a printer during the day. Gary’s decision to be a news-photographer

coincided with Ken’s becoming The Star’s chief photographer.

From being a notoriously self-absorbed egotist who cared only for

his career and awards, Ken had become a champion of aspiring

photojournalists. Gary was one of a group of interns Ken had taken

on at The Star in a programme to recruit talented young

photographers from the workshop into the newspaper. Gary would go

out with us to learn the ropes and he became a friend. He wanted to

be a bang-bang photographer. Despite his desire to cover conflict,

Gary was far too sensitive to deal with the violence, but he kept

his feelings to himself. On the surface he seemed to handle the

emotional aspect of the violence OK. We had no idea about his

dysfunctional family past and how he blamed himself for not having

been around when his father committed suicide. Sometimes I would

catch myself looking at Gary and wondering what was going on in his

mind, but I was too preoccupied to follow up on any of the small

signs that might have indicated a real problem. It was only later

that we understood the full effect that the accumulated trauma was

having on him.

The stress from what we were seeing and the at

times callous act of taking pictures was making an impact on all of

us. Ken was waking up in the middle of the night sweating and

screaming about things he had seen. Joao had become quiet and

withdrawn, and I sank into a deep depression that I only clawed my

way out of years later. Kevin was the most outwardly affected and

that meant that life as his friend could be demanding. He seemed to

have no borders, no emotional boundaries - everything that happened

to him would penetrate his very being and he let all that was

inside him just pour on out. The highs of boundless energy and

infectious joy would inevitably crash and then we would get the

despondent midnight calls. Joao, Ken and I all had our turns at

spending hours talking to a weeping Kevin until he had been soothed

or grown exhausted enough to sleep. But through it all, Kevin had a

way about him, an openness to pain, a generosity with his time and

affection which meant it was easy to overlook those lapses and

become even closer friends.

Maybe it was because his emotions were always right

up front that Kevin was the most candid of us all about the effect

that covering the violence was having on him. He was having a beer

at a pub opposite The Star one Saturday afternoon when Joao

came in after covering an uneventful political funeral. They

listened to a radio report that three people had died in clashes

following the burial. Joao wanted to go back to the township, but

Kevin said it was getting dark and talked him out of the idea.

After several more beers, Kevin recounted a recurrent nightmare

that was plaguing his sleep. In the dream, he was near death, lying

on the ground, crucified to a wooden beam, unable to move. A

television camera with a massive lens zoomed closer and closer in

on his face, until Kevin would wake up screaming. Kevin thought

that the dream meant it might be time to leave photography.

When Kevin told me about the same nightmare some

time later, he described the feelings of helplessness, the anger,

the fear he lived though in that dream. It was all that he imagined

our subjects must feel towards us in their last moments as we

documented their deaths. The dream had variations: sometimes Kevin

was the photographer, not the victim, and in that version, the

‘dead’ man would roll over and grab him by the ankle, holding him

captive with bloody hands.

Some weeks previously, in a lawless Sowetan shanty

town called Chicken Farm, Kevin and I had been following armed

policemen as they ran through the shacks, plunging downhill along

rough tracks muddy with raw sewage. At a clearing near a stream, we

saw a woman in rural Zulu dress wailing in grief, her hands

clutching her head. In front of her, a middle-aged man was lying on

his back, his arms stretched out on either side of him along a

thick wooden beam. It looked as if he had been crucified. His

earlobes, pierced and enlarged in the traditional Zulu fashion,

were filled with blood from several head wounds. There is no

question that a professional thrill ran through me: it was a scene

that could be an icon of the civil war. Kevin and I descended on

the corpse, but once we started to photograph, I found

myself struggling and failing to capture this image of the

crucifixion properly. I was unnerved, jittery, my hands were

shaking involuntarily. Perhaps it was because of the woman wailing

or memories of childhood religion, of Christ on the cross. I looked

at Kevin; he looked stunned. Suddenly the corpse groaned and rolled

on to its side. We leaped back in terror - we had been so certain

he was dead. I will never forget that moment of horror, but unlike

Kevin, I had no nightmares; at least none that I could recall in my

waking hours.

An American consultant hired in November of 1992 to

revamp the look of The Star was convinced that Joao was

suffering from posttraumatic stress syndrome, similar to what he’d

seen among photographers in Vietnam. Management agreed and, despite

protests from both Ken and Joao, he was told to stop going to the

townships. South Africa’s isolation from the world during the

apartheid years meant that any foreigner was automatically granted

expert status and respect, often beyond their due. Joao was

assigned to cover the effect of pollution on a pond in a wealthy

white suburb of Johannesburg. While walking disconsolately around

the sad pond, he noticed a duck waddling unsteadily towards him.

The duck collapsed and died at his feet. Back at the newspaper, he

printed the series as a montage with the mischievous caption

‘Going, going, gone’ and presented it to the photo desk. The

consultant was appalled and urged the newspaper to get Joao

psychological help.

Late that same night, a ‘press alert’ came across

on the pager. An entire family had been in slain in Sebokeng, a

sprawling black township south of Johannesburg that was plagued by

mysterious killings and massacres and drive-by shootings. Kevin and

Joao exchanged calls with Heidi and me, and despite the heavy rain

and our anxiety about the fact that it was well after dark, we

decided to go. The common wisdom among journalists was to never

enter conflict zones after dark: things were different at night;

people behaved without restraint. And we would have to use our

flashes to get pictures - risky as the bright light going off

spooked people and could attract gunfire.

The rain was bucketing down as we raced south in

Kevin’s little

pick-up. Heidi and I huddled against the cold in the fibreglass

canopy on the back, bracing against each other as the car

aquaplaned unpredictably every time it hit a patch of standing

water on the road. We were uncertain about the wisdom of the foray:

rumours of white agents provocateurs taking part in killings in the

black townships meant that whites were increasingly treated with

hostility. Sebokeng was probably the most dangerous township for

journalists to work in, but we were determined to try to expose

what was going on. When we got there, the dark streets were

deserted. We had no way of finding the house as there were few

street signs and residents had taken to painting over their house

numbers for fear of being targeted for attack. The killings were so

indiscriminate that people had devised convoluted theories as to

who might be the next target-a situation which made wandering

strangers seem to be a potential threat.

Usually we could ask people for directions or

follow our noses to the right place, but the rain and the fear of

being out at night meant that there was no one around to help. We

started to regret our decision: to the armed self-defence unit

members that kept watch, we must have looked like killers

ourselves, cruising around looking for victims. We crept fearfully

along the main streets, hoping to stumble on to the right house,

until we saw a police armoured vehicle lumbering along, the deep

growl of its engine breaking the silence. They were surprised to

see whites there, but agreed to let us follow them to the house.

While we waited for the detectives to finish their investigation,

we found shelter from the wet with the survivors in a back room.

The rain drummed on the tin roof, leaking through holes. Under the

dim glow of a naked light-bulb, 21-year-old Jeremiah Zwane related

how two men had burst through the front door and thrown a tear-gas

canister into the room, then gone from room to room shooting

everyone they found. His father and his brother had been gunned

down in one bedroom. Jeremiah’s sister, Aubrey, just seven years

old, had tried in vain to hide in her parent’ bedroom closet. She

lay on her back in a pool of blood alongside her dead mother. Shot

in the face and chest, her little body was a deeply shocking sight

even after the many gruesome images

we had photographed over the previous two years. A visiting

teenage cousin had been shot dead in the lounge. Another teenage

sister had died on the way to hospital, but her two-day-old baby

had somehow survived the attack unhurt. The house looked like a

scene in a horror movie, but this was real. The smell of blood was

heavy in the damp air.

The four of us were the only journalists out in

Sebokeng that night, despite the fact that every news organization

and most journalists had received the message of the killing on

their pagers as we had. We were convinced that the only way to stop

such killing was to show what those deaths looked like, what those

daily body counts actually meant.

The Star, which had suggested Joao lay off

covering township violence, ran the story he had reported and two

pictures, one on the front page. I transmitted pictures to the AP

and The New York Times. Without our pictures, the only

source of information on the massacre would have been spokesmen for

the police and the political parties. Editors from most domestic

and foreign media organizations still took police reports as

factual even though the police were clearly a part of the problem.

I remember many infuriating discussions with Renfrew, who was then

still the AP bureau chief, about police and military involvement in

the killings - he would patronizingly accuse me of being

politically biased and naïve, but the AP and almost every other

news organization chose to believe the government’s propaganda. The

public would have been given information about yet another massacre

from the people who were actually involved in many of the killings,

as would be proved years later. It seemed that the international

and domestic public were all too ready to believe that people who

sometimes dressed in skins and could not speak English properly

must be barbaric, while the white politicians and officials who

spoke so logically and kept the trains running on time could not

possibly be implicated in the murders. And yet despite our attempts

to tell the truth, through our reporting and in our captions, our

pictures played an unwitting part in the deception - our images

from Sebokeng that night showed horribly dead black people and

white policemen in uniform taking the bodies away, investigating

their deaths. The impression was

of the police helping the victims. Our pictures could not show

that they had arrived hours after the emergency calls for help:

they could not show the absolute certainty of the survivors that

security forces had been involved in the attack.