10

FLIES AND HUNGRY PEOPLE

Vulture stalked white piped lie forever wasted

your life in lack-and-white Kevin Carter

from ‘Kevin Carter’ by the Manic Street

Preachers, Sony Music/Columbia, August 1996

March 1993

Kevin’s eyes could not be misinterpreted when Joao

told him that he was prepared to go to Sudan. Kevin wanted to go

too, it was his chance to escape the web of problems he felt

trapped in.

For Kevin, the war in Sudan - said to be a genocide

of the Christian Dinka and Nuer tribes by the Islamic government -

was a chance to free himself of his crazy infatuation. So one-sided

was the relationship that a desperate love letter he had dropped

off at the woman’s house was read out to the guests at a dinner

party she was giving, leaving them uncomfortably amused. He also

wanted to get off the white pipe. Sudan seemed to present the

possibility of making everything right and revitalizing his career,

which seemed to have come to a dead-end at the cash-strapped

Weekly Mail. The newspaper had not been interested in the

Sudan trip and insisted he take leave if he wanted to go.

Kevin approached various people for whom he had

freelanced in the past. Paul Velasco, then owner of the South

African photo-agency

SouthLight (now renamed as PictureNet Africa), advanced him some

money, as did Denis Farrell at the AP; he also borrowed some from

me. Combined with his salary, this was enough to cover the air

ticket and hotel accommodation while still meeting his commitments

back home.

Kevin was on a high, motivated and enthusiastic

about the trip. He was on the rebound from his spectacularly

unsuccessful relationship when he met Kathy Davidson at a party. A

good-looking, intelligent and pleasant school teacher - the perfect

antidote to his usual choice of hard-edged women. Kathy found him

intriguing and attractive, and let him have her telephone

number.

For Joao, the excursion was a chance to expand his

career. He was still working at The Star when a former

photographer, Rob Hadley, who had taken a job with the United

Nations’ Operation Lifeline Sudan project, had offered him and

Kevin the chance to get into southern Sudan with the rebels. Joao

had jumped at the offer, and began making the arrangements.

Newsweek Magazine had promised money-a guarantee to secure a

first look at the pictures. When Joao approached Ken to get leave

for the trip, Ken instead secured Joao an assignment from The

Star’s foreign news service. If his pictures from Sudan were as

strong as those from his self-funded trip to Somalia the previous

year, it could lead to other assignments with major international

magazines. His dream of being a war-photographer beyond the borders

of South Africa had begun to materialize.

Fax messages from Rob stressed the latest downturn

in Sudan - the major rebel factions had split into tribally based

groupings with the result that entire villages had been massacred

by opposing tribal militia, and the government had seized the

opportunity to launch a massive offensive against the divided

rebels. The part of southern Sudan that Joao and Kevin wanted to

get to was an especially vulnerable area in the remote hinterland

dubbed the ‘the Famine Triangle’ by aid workers.

The Southern tribes of Sudan are Christian or

animist and had been grouped together under the rebel umbrella

group, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). They had been

fighting for

autonomy from the Khartoum government, which had been dominated by

Islamic northerners ever since independence in 1956. The low-key

war had been spurred to new intensity in the 80s by the

government’s adoption of Islamic Sharia Law. The story which Joao

and Kevin hoped to cover was the recent bloody split in the SPLA.

Sudan is a notoriously difficult country to work in, with a

government that refuses journalists entry to the south, and rebels

that are either pressshy or expert at manipulating the prying eyes

of outsiders. The breaking and forging of alliances makes it

difficult to predict the situation from one week to the next, and

aid organizations have great difficulty in getting food aid in with

any regularity.

Kevin and Joao prepared carefully for the trip. The

day before they left for the Kenyan capital of Nairobi - the best

transit point for trips to southern Sudan - they met at Kevin’s

rented house in the Johannesburg suburb of Troyeville. Kevin’s

entire bedroom was covered by numerous packets and bags. Ken had

accompanied Kevin on a shopping trip for everything from mosquito

nets to dehydrated food - they did not know what they might need.

Joao and Kevin sat on the bed, laughing and excited, and shared a

joint. Ken was drawn into their excitement, and took a picture,

then left them to finish their packing.

The next day, after a five-hour flight north, Kevin

and Joao arrived in Nairobi and went to the Parkview Hotel, one of

the cheaper, rather dingy, hotels that cater to backpackers and

other budget travellers. To economize, they shared a room that

enjoyed a view of a muddy alley. The telephone only reached as far

as the lethargic receptionist and there was no television.

It was a Sunday in Nairobi and deathly quiet. They

went for a walk, Kevin hyper-active, striding and talking fast.

They ended up drinking beer on the colonial Oaktree Hotel’s

veranda, watching the tropical sun set over the city. Kevin was

excited and happy to be in Nairobi, and they were both looking

forward to getting to Sudan.

The next day things started going wrong. Kevin

tried to change a 100-dollar bill and the bank rejected it - it was

a counterfeit. They contacted Rob at the Operation Lifeline Sudan

headquarters at Girgiri

on the outskirts of Nairobi, but further disappointment was in

store for them. The plan had been that they would fly in on a food

drop, and spend about a week on the ground before being picked up

on the next food delivery, but an upsurge in fighting meant it was

unsafe for the planes to land, and the aid flights had been

suspended. Their trip was put on hold - indefinitely.

Every day they went out to the UN compound to see

if the situation had changed, but for five days they got the same

negative answer. The disappointment built up in the tiny hotel

room. Joao was furious, unhappy. All his careful planning was going

down the toilet. Time passed slowly and painfully; they spent

sparingly and ate in increasingly cheap restaurants. They did the

rounds of the aid agencies, to see if any of the other

organizations were flying in, despite the fighting. They abandoned

the more expensive personal taxis and began using matatus - the

colourful local minibus taxis which pack in up to 20 passengers.

The drivers seemed to be in competition as to who could fit the

largest disco speakers in their vehicles. When the buses were very

full, the speakers would serve as seats, and on one such crammed

trip Kevin had to sit on a speaker. The reggae that blared out of

the speaker was too loud for anyone to speak and be heard, so Kevin

sat back with an amused look of contentment, and took the

occasional picture through the window with his cherished old Leica

M3.

In spite of their lack of progress, Kevin was

having a good time. All he could talk about was how this trip was

going to work out and how everything was going to be great. He made

plans to resign from the Weekly Mail, go freelance and

pursue a relationship with Kathy - get some stability in his life.

Joao, on the other hand, was uptight. The pressure was getting to

him, he had sold the trip to The Star and Newsweek on

the strength of combat images, and there he was, stuck in Nairobi

with little hope of getting near the fighting any time soon.

Then suddenly there was a UN trip to Juba-a

besieged, government-held town in the south of Sudan. A barge

carrying food aid had been travelling up the Nile and had finally

made it to Juba. It was an ‘in-and-out’, a one-day affair. Since

Kevin had the guarantee from

the AP, the UN put him on the plane flying in. There was no room

for Joao, who had to stay behind. He was livid. Joao had done most

of the preparatory work, set up the main part of the trip, and

Kevin, who had mostly just followed his lead, was getting into

Sudan while he cooled his heels. He assumed the worst: this was it

- there would be no other chance to get to Sudan and he would

return home without having shot a frame.

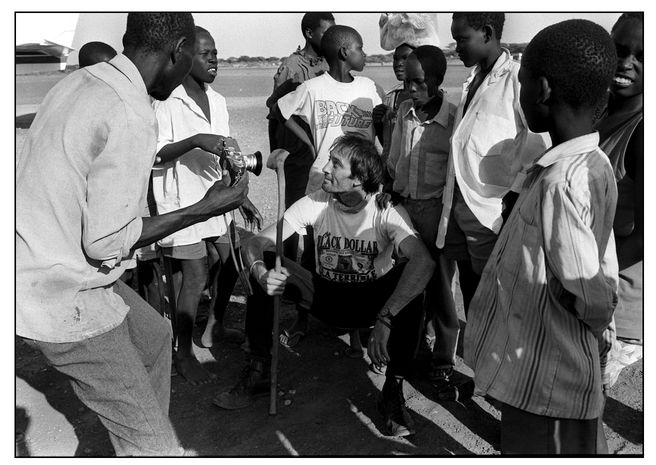

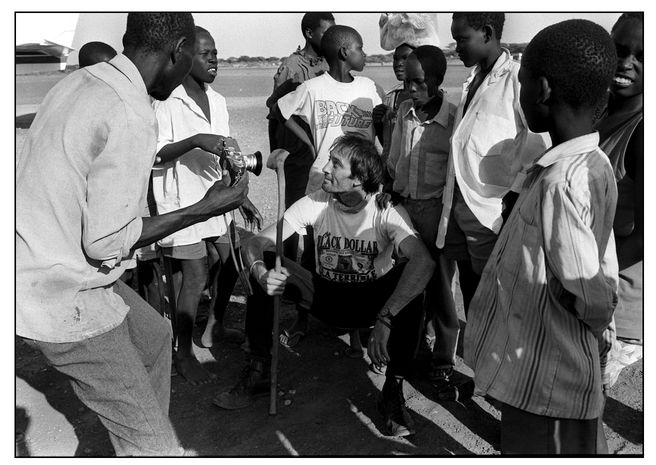

Kevin Carter plays with children as a local

villager looks at his camera in the Kenyan border settlement of

Lokichokio, March 1993. (Joao Silva)

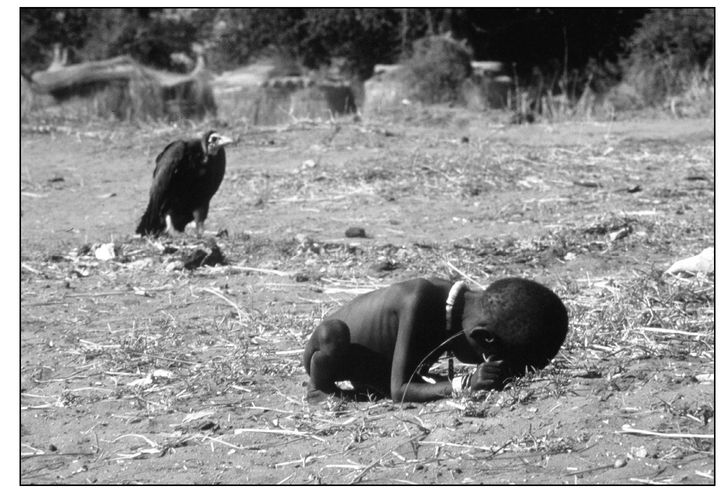

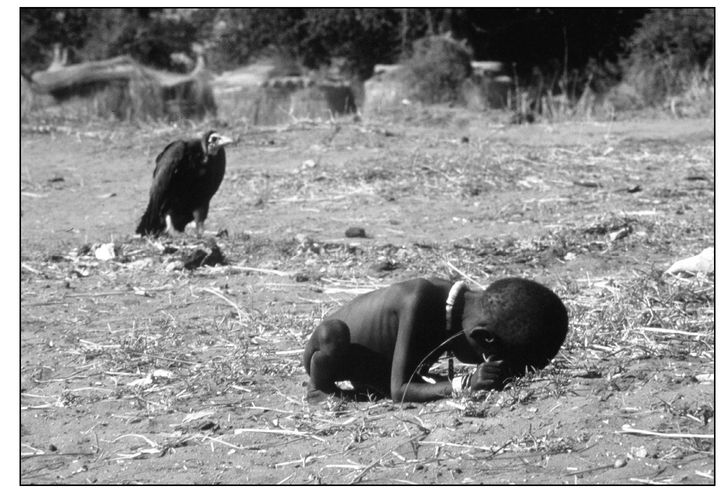

A vulture seems to stalk a starving child in the

southern Sudanese hamlet of Ayod, March 1993. This picture would

win Kevin Carter the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography. (Kevin

Carter/Corbis Sygma)

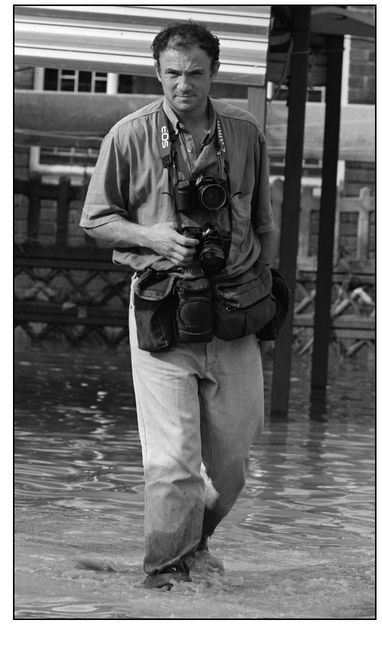

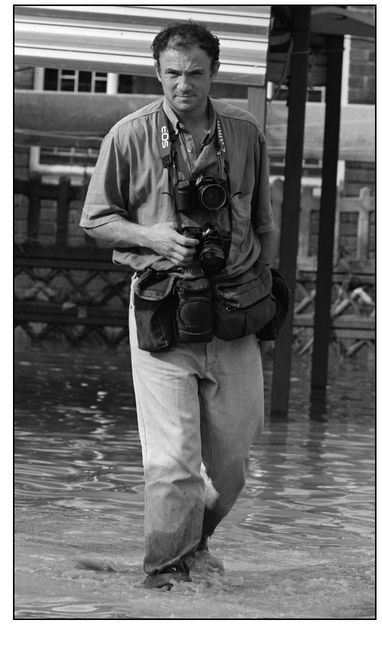

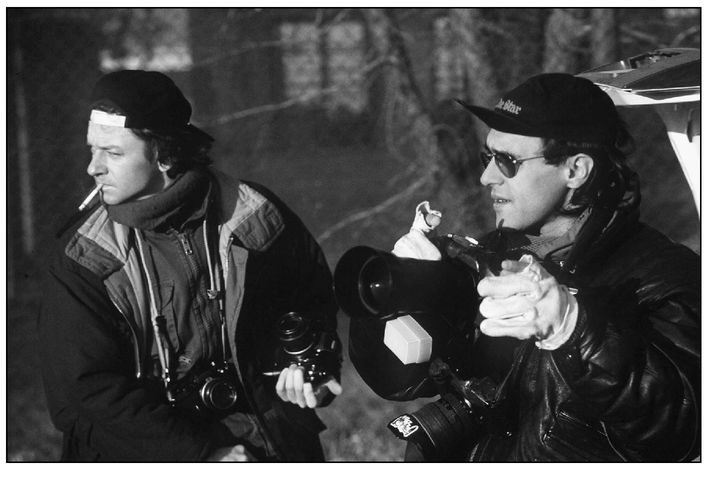

Left:

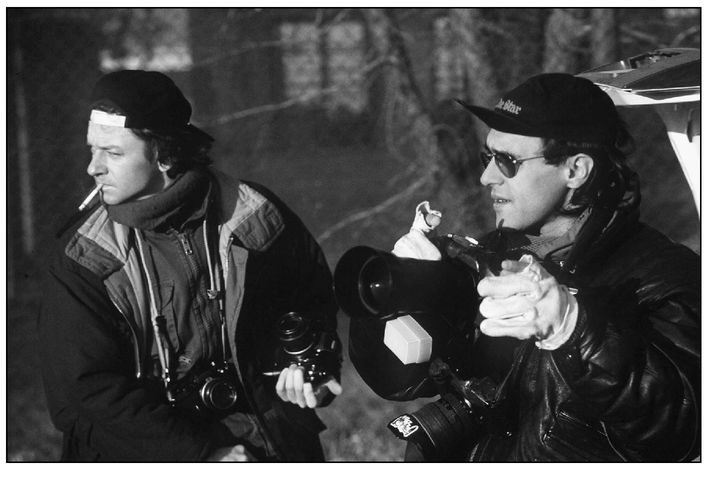

Greg Marinovich covering floods in the Kwa-Zulu

Natal town of Ladysmith, 1996, shortly before he left to take up a

post in Jerusalem for the Associated Press. (Joao Silva)

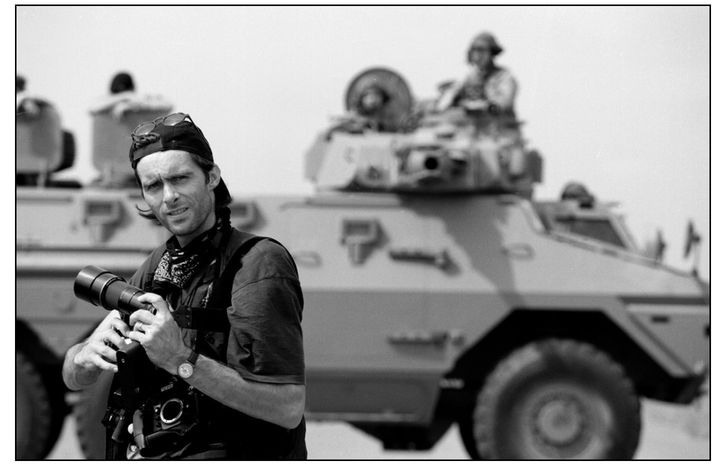

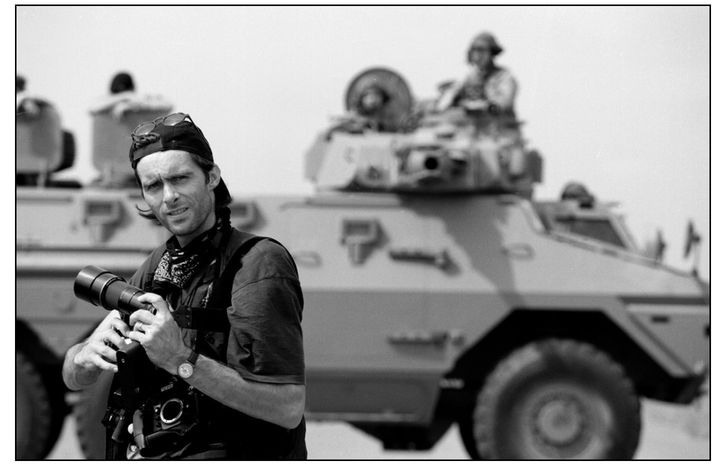

Below:

Ken Oosterbroek, with a South African Defence

Force armoured vehicle behind him, during the fall of the homeland

of Ciskei, February 1994. (Joao Silva)

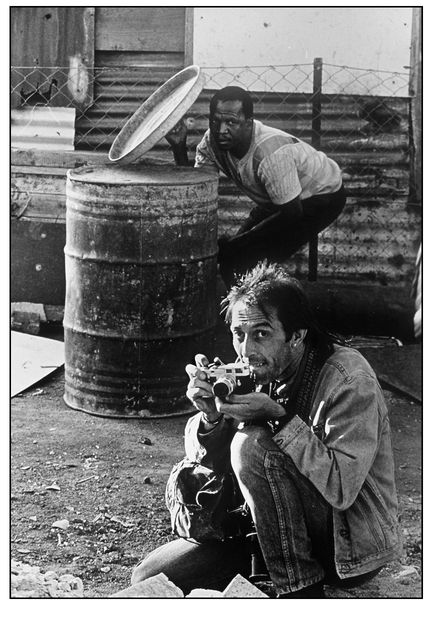

Right:

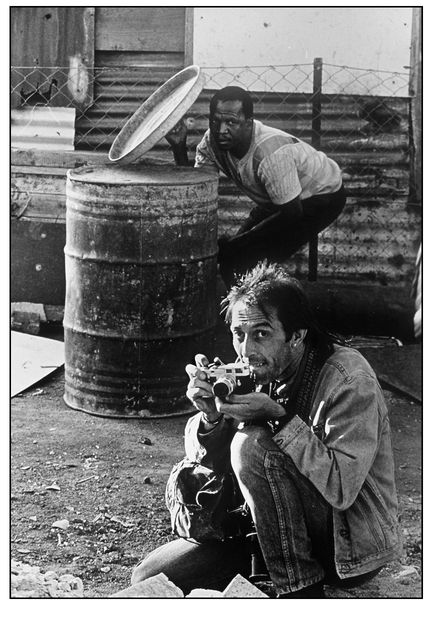

Kevin Carter crouches while covering clashes

between the ANC and Inkatha in Alexandra township, Johannesburg.

(Guy Adams)

Below:

Gary Bernard, left, and Joao Silva on a winter

morning in Soweto township, July 1994. (Greg Marinovich)

Three dead men lie in the street where they were

gunned down during a battle between Inkatha and the ANC in Soweto’s

Dobsonville suburb. The graffiti reads ‘Remember - Life owes you

nothing - you owe everything to

life!!!’ (Joao Silva)

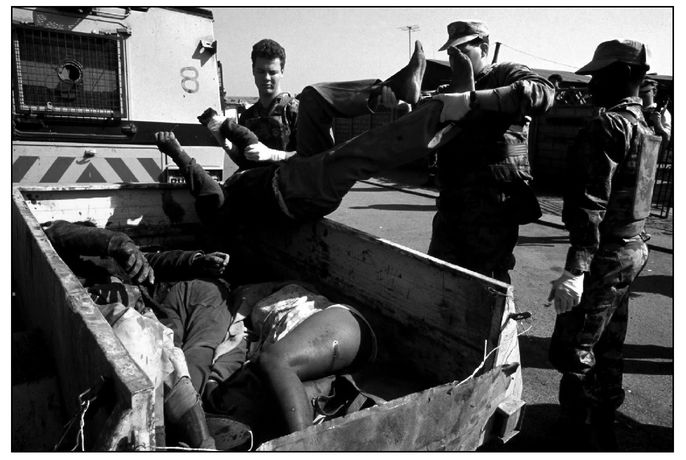

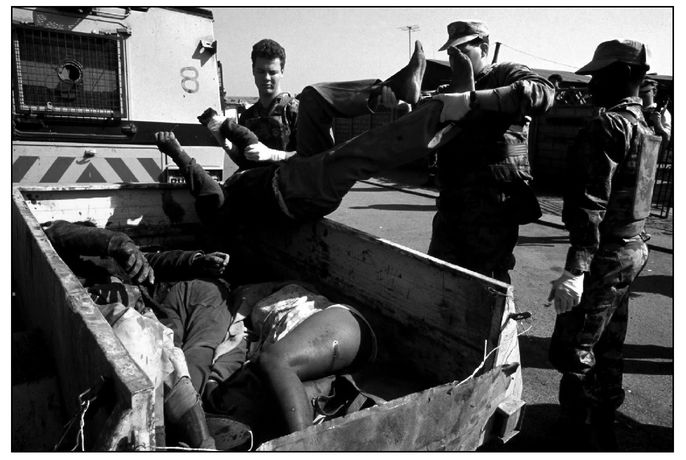

Policemen load corpses into an open trailer after

a night’s violence between ANC and IFP supporters in Thokoza, July

1993. Sixty people were killed in the township that weekend. (Joao

Silva)

An Inkatha supporter lies dead amongst his

traditional Zulu weapons after several hundred warriors tried to

storm the ANC’s headquarters, Shell House, during a march in

downtown Johannesburg, 1994. Several Zulus were killed, and it

became known as the Shell House Massacre. (Greg Marinovich)

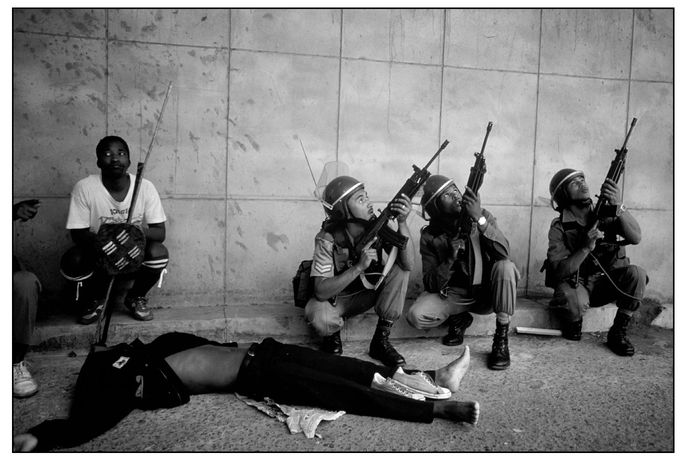

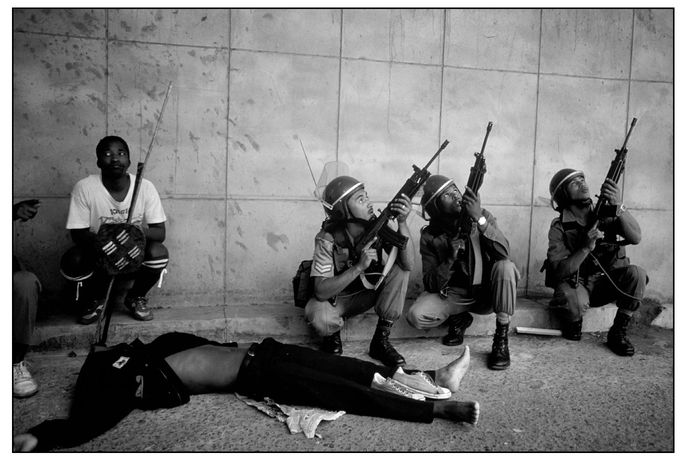

Another Inkatha supporter lies dead, with his

shoes taken off for his journey to the next world, as soldiers look

for the sniper who killed him during the Shell House Massacre.

(Greg Marinovich)

Kevin Carter during a late night shift as disk

jockey at the Johannesburg station, Radio 702. (Joao Silva)

The print-ready artwork from the article entitled

‘Bang-Bang Paparazzi’, which featured in the South African

magazine, Living, that led to a subsequent article called

‘The Bang-Bang Club’, featuring Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken

Oosterbroek and Joao Silva. (Joao Silva)

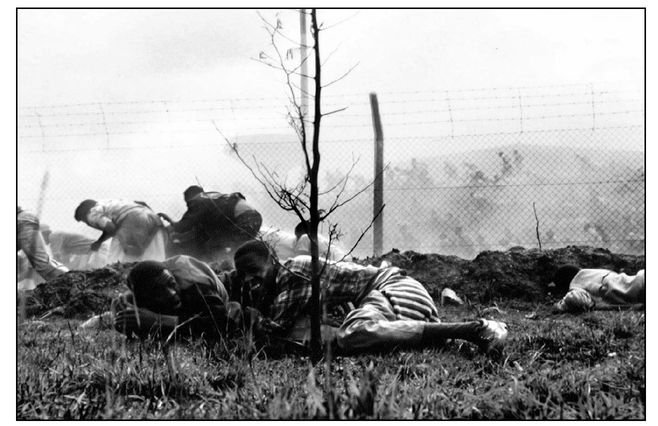

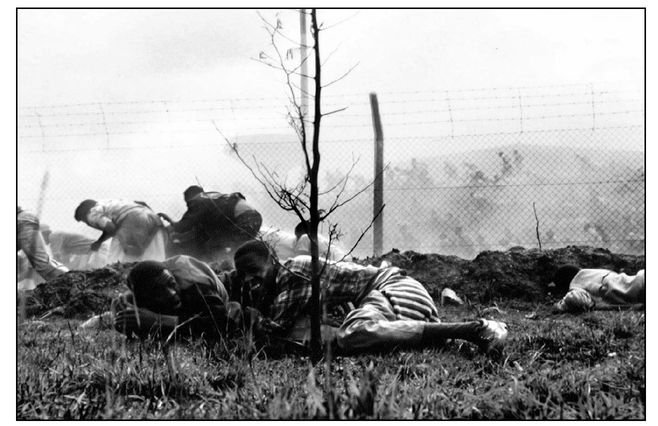

Bisho, 1993. Ciskeien homeland soldiers opened

fire on tens of thousands of ANC supporters who marched across the

South African border to demand the Ciskei disband. Some 26 ANC

marchers were killed. (Greg Marinovich)

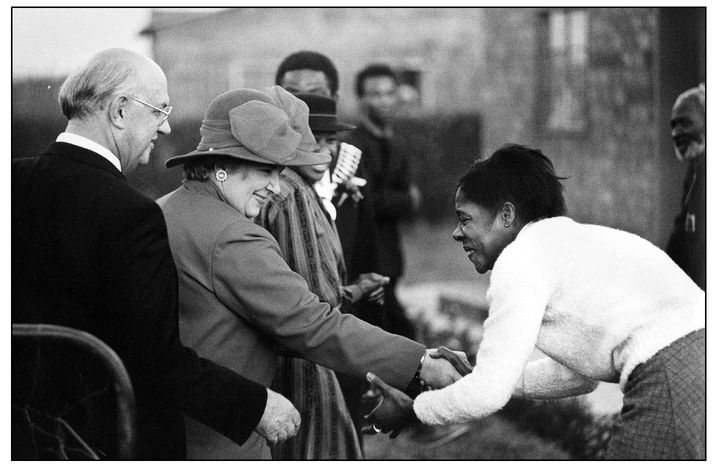

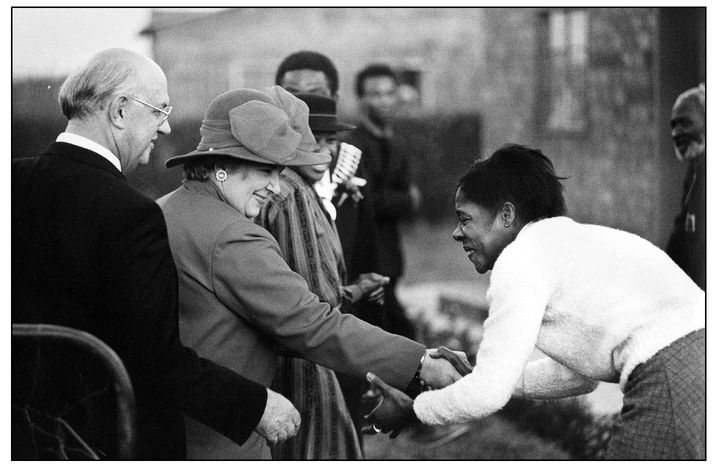

Then State President of South Africa, PW Botha,

and his wife Elize, are greeted by a woman in the black township of

Sebokeng, south of Johannesburg, in the late 1980s. (Ken

Oosterbroek / The Star)

ANC fighters carry a wounded comrade during

clashes with Inkatha supporters in Alexandra township,

Johannesburg. (Kevin Carter/Corbis Sygma)

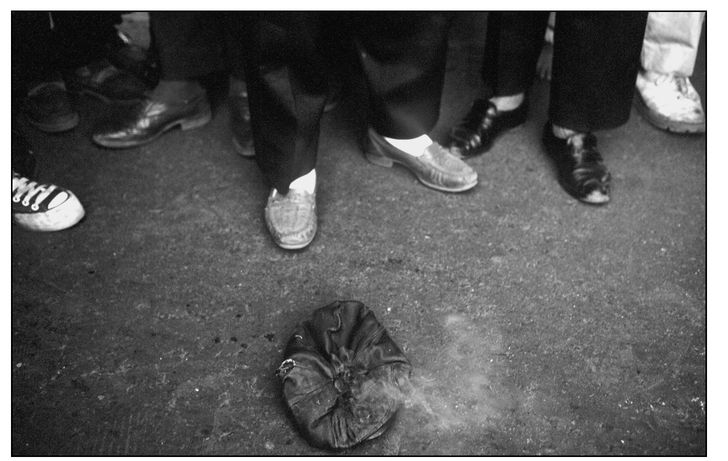

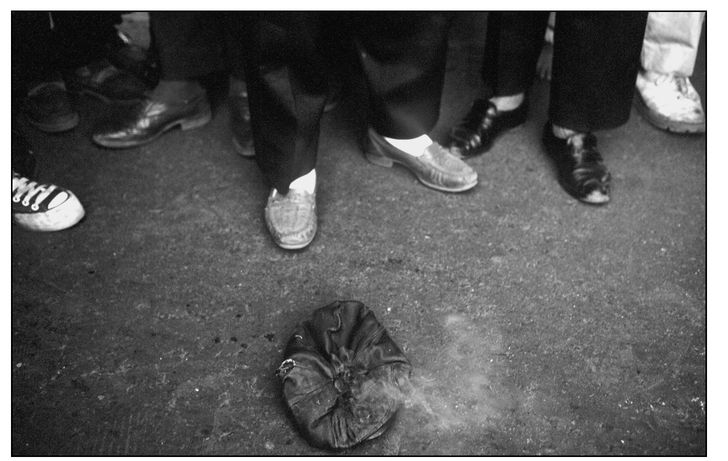

Smoke rises from a cap of an ANC self-defence-unit

member shot in the head at pointblank range after he mistakenly

opened the door to Inkatha gunmen in the dead zone in Thokoza

township, 1995. Four other ANC militants were killed. (Greg

Marinovich)

What Joao and Kevin did not know was that the UN

was having great difficulties in securing funding for Sudan. An

appeal earlier in the year for 190 million dollars had barely

raised a quarter of that. The UN hoped to publicize the famine in

which hundreds of thousands of southern tribesmen faced starvation.

Without publicity to show the need, it was difficult for aid

organizations to sustain funding. There is nothing like a disaster

to boost an aid agency’s profile, and they needed to have the media

cover the existence of the emergency. There are those who insist

the war in Sudan would have ended decades ago if food and other aid

had not been allowed to sustain the fighters; that the aid agencies

and their food were manipulated, used by both government and rebels

as a weapon of blackmail against the civilians in their areas of

control, but Joao and Kevin knew none of this - they just wanted to

get in and shoot pictures.

Kevin flew off to Juba while Joao sat brooding in

the depressing hotel room. It was still daylight when Kevin

returned. The trip had been a waste of time, he told Joao. They had

landed, been taken to a pier on the While Nile, shown a barge with

food being unloaded, suffered through a press briefing - and that

was it. Despite the barge having had to travel for two months up

the great river, during which it had been raided for over half of

its cargo by famine-stricken people on the way, the only half-way

interesting pictures Kevin found were of children scrambling for

some grain that had spilled on to the dock. Kevin tried to

alleviate Joao’s sour mood by showing him the negatives to prove

just how useless the trip had been. Though Joao realized he had

missed nothing, the knowledge did not make him feel any better.

Joao was given to omens and they were looking pretty bad at that

moment.

They decided to give it two more days and if

nothing changed, they would head home. But then they received the

news they had been waiting for: one of the rebel factions had given

permission for the UN to fly in. In addition to the cargo plane

carrying the food, Rob was going in on a light plane to assess the

situation on the ground. Joao and Kevin were welcome to join him,

but there was no guarantee as to when they could be picked up

again. The following afternoon they were in the air, once again

buoyant at the change in their fortunes. Three hours later, they

landed just inside Kenya’s northern border, at the settlement of

Lokichokio, just a few hundred metres from Sudan. Lokichokio was a

tent-city, an UN forward-base for the big Hercules cargo aircraft

that flew food and medical supplies into the famine areas.

Kevin and Joao were allocated a tent, then they had

dinner out in the open, under a crystalline African sky. Dinner was

good and the beer was cold, and they hoped to have more under the

seamless canopy of stars, but the bar closed soon after ten. Back

in their tent they could not sleep - too much excitement, too many

thoughts of what might happen to them tomorrow.

‘What do you think is waiting for us there?’ Kevin

asked, his voice loud in the dark silence that had settled on the

camp. Joao could see Kevin’s profile, lit by the glowing tip of his

cigarette.

‘Flies and hungry people, from what I’ve heard,’

Joao replied.

Their conversation skipped from topic after topic,

but unlike all other similar conversations Joao had persevered

through with Kevin, this time it was all positive. No

self-indulgence, no self-pity. The future looked bright: Kevin was

confident that the trip would be successful, that he would be able

to cover his costs and make some money. This new girl, Kathy, was

going to be just right for him. But mostly they spoke about South

Africa, their work, the violence and where the country was heading

in the coming years and the upcoming vote. The first elections that

all South Africans could finally take part in were just 13 months

away.

The conversation came around to Kevin’s tattoo. He

had a

misshapen map of Africa drawn on his right shoulder, clearly the

work of an amateur. Joao told him he had seen better tattoos on

convicts. Joao also had a tattoo on his right upper arm showing a

winged angel, with the motto ACCEPT NO LIMITS on unfurled scrolls.

It was also less than fantastically well drawn, but it was a work

of art compared to Kevin’s.

After a lengthy discussion of tattoos, they decided

Kevin’s should be re-done, reshaped so that the continent would

look like the real thing, all in black, but with a single red tear

coming out of South Africa and spilling on to his arm. The tear

would somehow signify Kevin’s own pain as well as the pain of those

whom he had photographed. They laughed that it would at least look

better than his current tattoo. The pilot, who was trying to sleep

in the adjoining tent, pleaded with them to keep quiet. They

lowered their voices, noticing that dawn was not far off - they

could hear the sounds of workers preparing breakfast.

Two hours later, their plane touched down in the

tiny southern Sudanese hamlet of Ayod. It taxied to a halt at the

end of the dirt airstrip and the pilot turned the plane in to

position for a quick take-off, should it prove necessary. Half-way

through the turn the front of the little plane lurched to an abrupt

halt. They climbed out and saw that the front wheel had sunk into

thick sand and the plane was stuck. It was nothing serious, the

plane was undamaged, and they had started to push it out of the

beach-like sand when they saw the massive cargo plane approaching.

The cargo plane was making its approach for descent. Fortunately,

dozens of Sudanese had come to greet the plane, the sound of

aircraft meant food, and they quickly helped to wheel the little

plane off the runway, averting what could have become a complicated

situation.

As the cargo plane landed, its giant propellers

raised a storm of sand and pebbles. The Sudanese crouched low

alongside the runway, braving the hot, stinging blasts to be nearer

the food. There is never enough food in these circumstances to feed

everyone and the hungry villagers rushed the plane to try to ensure

that they got their share of nutritious biscuits and maize meal.

Those too weak to get to the runway

had to rely on the aid workers for food. Some 200 metres from the

runway, a low brick building from which the food aid was

distributed stood out among the surrounding conical huts made of

long thatching grass. That was Ayod. The first food consignment

after months without aid attracted a pushing crowd of hungry

Sudanese. They wore patched rags or walked around naked. Mothers

who had joined the throng waiting for food left their children on

the sandy ground nearby. The small food aid building also served as

a clinic and was full of ill and starving people. There were those

who needed special care if they were to survive, and others that

could only be comforted before they died. Kevin and Joao separated.

There were pictures everywhere. Once in a while, Kevin would seek

out Joao to tell him about something shocking he had just

photographed. In one of those foul-smelling rooms, Joao saw a

skinny child lying spread-eagled on the dirt floor. It was dark and

he struggled with the light, trying to get a frame. Kevin joined

him and went down on to his knees to shoot the picture; he then

looked up at Joao, wide-eyed. Despite all the happy anticipation of

the night before, all the excitement had disappeared now that he

was witnessing the effects of the war-induced famine.

Joao left the room. He wanted to find rebel

soldiers who could take him to someone in authority. Their plane

would take off in an hour and they needed to secure rebel

permission to stay on. Joao found a group of fighters. They were

dressed in rags, the only indication that they were indeed soldiers

were the AK-47 assault rifles hanging limply from their shoulders.

Kevin joined Joao and they tried talking to a rebel with deep

traditional scars etched vertically on his cheeks, but the fighter

spoke no English and communication rapidly broke down. They kept

frozen grins on their faces as they tried to mime their way through

the conversation. The only thing that was apparent was that the

rebel had developed an interest in Kevin’s wristwatch. Somehow,

Kevin gave the rebel his watch. Joao was surprised, but understood

Kevin to be giving the soldier the cheap watch in an effort to ease

his conscience about all those hungry people he could not help - or

to secure goodwill to help them get across to the fighting.

They separated again. Joao photographed a

half-naked man walking past him, completely oblivious to the white

stranger. He went back inside the clinic complex, where he was told

that permission to stay had to be obtained from the rebel

commander, Riek Mashar, who could most probably be found at Kongor.

This was good news; their little UN plane was heading there

next.

Joao left the cool of the clinic and returned to

the harsh sun and headed in the general direction of the runway, to

where he had last seen Kevin. He came across a child lying on its

face under the hot sun - he took a picture. Joao assumed the child

had been left there by its mother while she went for food. He moved

on to where he could see a man on all fours, digging at the arid

soil with a hand tool of some sort, trying to plant seeds in the

desiccated ground, hoping that the rains would ultimately arrive.

Kevin had seen Joao and was coming towards him, moving fast,

frantic. ‘Man,’ he put one hand on Joao’s shoulder, the other

covered his eyes. ‘You won’t believe what I’ve just shot!’ He was

wiping his eyes, but there were no tears, it was as if he was

trying to obliterate the memory of what he had photographed, of

what was burnt on to his retina.

Joao gave him a look. He didn’t like this

‘I-shot-shit’ at the best of times, much less when he had not seen

any outstanding picture opportunities, but Kevin continued, not

even noticing his friend’s sceptical look. ‘I was shooting this kid

on her knees, and then changed my angle, and suddenly there was

this vulture right behind her!’ Kevin was excited now, and talking

fast. ‘And I just kept shooting - shots lots of film!’ His arms

were all over the place, as they usually were when he was

recounting something exciting.

Joao perked up, ‘Where?’ looking around, hoping to

catch up on this amazing-sounding scene. If it were still there, he

needed to shoot it. ‘Right here!’ Kevin said, pointing frantically

fifty metres in front of them. Joao could see a child lying face

down on the dry, grey-brown soil. The child looked similar to the

one Joao had photographed a little earlier, but there had been no

vulture near it then, and there was none now. ‘I’ve just finished

chasing the vulture away!’ Kevin’s eyes were

wild, he was speaking too fast, and losing words. He kept wiping

at his eyes with the green bandanna he wore around his neck. ‘I see

all this, and all I can think of is Megan.’ He lit a cigarette and

dragged hard, getting more emotional by the second, the thin grey

smoke disappearing into the air. ‘I can’t wait to hug her when I

get home.’

Joao sensed immediately that he had missed out on a

big moment, and, imagining what the picture would look like from

Kevin’s description, knew his own take was going to look bad. Joao

consoled himself with the thought that Kevin always got overly

excited. He, on the other hand, had nothing to get excited about at

all. But he was prepared to wait and see the pictures, being used

to watching Kevin get electrified about images that sometimes

turned out to be very average. Minutes later, they were back in the

plane and leaving Ayod behind.

Kevin was telling Rob and the pilot all about the

moment he had just experienced and how it made him feel, and that

all he could think of was his own fortunate young daughter back

home. He repeated how much he looked forward to seeing her, to

hugging and kissing her. ‘Just five minutes in Sudan and he is

blabbering about how terrible it is and how he’d never seen

anything like it, all because of war,’ Joao thought. Up in the air,

away from the realities, Kevin’s mood improved and he seemed a

little happier. The realization of what he had shot was seeping in,

for both Kevin and Joao. Joao sat quietly in his seat, withdrawn,

disappointed and wishing he were elsewhere. The flies that had

persistently followed them at the camp took off with them, making

themselves at home in the plane. ‘So far my prediction is right,’

muttered Joao miserably to himself; he felt he had nothing but

pictures of some hungry kids and half-naked men with guns. ‘Flies

and skinny people.’

In New York, four years later, Nancy Lee, then

The New York Times picture editor, bought me lunch and told

me about how the vulture picture came to be published in the

Times.

‘It all started when we were trying to illustrate a

story out of the Sudan and it was really hard. Very few people got

in. Nancy Buirski

called around. She called you and you said Kevin had

pictures.’

That phone call from The New York Times’s

foreign picture editor Nancy Buirski had come late at night, waking

me with its insistent ringing. There are few things I hate more

than those late-night calls - people seem to ignore time

differences, and I am partial to my sleep. Nancy Buirski wanted to

know if, by any chance, I had recent pictures from Sudan. They were

doing a story and needed to illustrate it. Their Nairobi

correspondent had been in Juba when a food aid barge had arrived

after 59 days of arduous and dangerous travel up the Nile. (It was

the same barge Kevin had flown in to photograph, before he and Joao

had both finally flown in to Ayod for those few, fateful

hours.)

I told her that I had never been there, but that a

friend of mine had returned from Sudan just a few days earlier with

a great picture: an image of a vulture stalking a starving child

who had collapsed in the sand. Was that the kind of thing they were

interested in? From what had been a long-shot phone call, suddenly

Nancy got excited. I gave her Kevin’s phone number. I had a strange

feeling, a kind of jealousy, an envy, about introducing that

picture to people. I, like many others, knew that it was going to

be a massive picture and had been telling Kevin that, encouraging

him to make the most of it, but when Nancy Buirski called me, I had

a moment when I thought about not telling her of it. It was silly,

and just a fleeting thought, maybe because he had shot it with a

lens borrowed from me, maybe because I liked being the only South

African Pulitzer-winner. In reality, I did not hesitate in telling

her about Kevin’s vulture picture, but the selfishness of that

short-lived, regretful thought has stayed with me, bothering

me.

When that picture and a selection of others were

finally transmitted to the Times, Nancy Buirski was waiting

at the machine for it to roll off. Nancy Lee says she cannot forget

the moment when she first saw the vulture picture - the

Times, at that time, still had the old-style wire machine

which would suddenly spit out prints, one at a time. Once she saw

the picture, she instructed Buirski to make sure that Kevin not

sell it to anyone else before they had published it.

Nancy Lee recalls that after the picture ran,

people started calling.

There was a lot of interest in what had happened to the girl. So

she called Kevin and asked him. He said she had continued on to the

feeding station. ‘Did you help her?’ ‘No, she got up and walked to

the feeding centre, we were very close, within sight of it.’ ‘So

you didn’t do anything, you didn’t help her?’ ‘No, but I know she

made it, I saw her.’

The Times then ran an Editors’ Note saying

that the girl had made it to the feeding station. But Nancy Lee was

still unsatisfied, ‘I remember Nancy Buirski and I both felt

uncomfortable. If he was that close to the feeding station and the

child was on the ground, then, having taken the picture - which

was, I think, important to do - why had he not gone there and got

help? What do you do in cases like this? What is the obligation of

any news professional in the face of tragedy in front of them? I

don’t know; I have a humanistic feeling about it and a journalistic

feeling about it. If something terrible is about to happen and you

can stop it, if you can do something to help once you’ve done your

job, why wouldn’t you? It bothered me, as a person. He could have

done it, it would have cost him nothing. She would have weighed

something like ten pounds. He could have picked her up and carried

her there, could have gone there and got someone to come back and

help her, whatever.

‘I don’t like to judge people, I was not there, I

do not know what the situation was, I don’t know. But I would have

helped the girl, me, as a person.’

Copyright 1993 The New York Times Company

The New York Times

March 30, 1993, Tuesday, Late Edition - Final

SECTION: Section A; Page 2; Column 6; Metropolitan Desk

The New York Times

March 30, 1993, Tuesday, Late Edition - Final

SECTION: Section A; Page 2; Column 6; Metropolitan Desk

Editors’ Note

A picture last Friday with an article about the

Sudan showed a little Sudanese girl who had collapsed from hunger

on the

trail to a feeding center in Ayod. A vulture lurked behind

her.

Many readers have asked about the fate of the girl.

The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her

trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she

reached the center.