CHAPTER 41

OUTSIDE, MRS. JENNINGS and the Dashwood sisters encountered a world transformed.

As their terrified retinue of remaining servants paddled Mrs. Jennings’s elegant gondola furiously towards the Ascension Station, Marianne and Elinor clutched the handles of their luggage, staring upwards at the curved ceiling of the Sub-Station Dome; it was clear now that what had appeared to be a couple of rogue swordfish, perhaps a handful, engaged in a quixotic effort to crack the glass where it abutted Mrs. Jennings’s docking, was in fact the smallest expression of an assault of unimaginable proportions. A thick blanket of fish coated every inch of the Station’s exterior, ramming again and again, in ragged rows, against the ceiling of the world. The Dome was cracked in a million places; it trembled under the weight of the fish ceaselessly battering themselves against it.

Men and women looked at each other with chilled expressions— or stared numbly ahead as they streamed through the canals in a mad dash for the Ascension Station. The waterways were crowded with people on rafts and gondolas and tugs and kayaks and skiffs; with people riding sea horses, sea cows, tortoises, sea lions; all imaginable means of conveyance had been pressed into use; one servant swam a desperate Australian crawl with a woman and two frightened infants strapped upon his back.

No longer were servants seen swimming outside the glass, trying with gutting knives or air-rifles to do battle against the swordfish, narwhals, humpbacks, silverfish, skates, dugongs, bass, and the other legions of fish that were massed against them—the enemy by now was too numerous. To reach the Ascension Station, and escape to safety before . . . the unspeakable occurred, was the goal of every mind.

Except for the one lone swimmer—either mad or courageous or both—who was suddenly seen paddling determinedly outside the glass.

“By God!” cried Marianne. “It’s Sir John!”

And nor was that intrepid luminary wearing a Ex-Domic Float-Suit, Sir John was stripped stark naked, but for a diving helmet and air-pack; in his right hand he clutched a glinting, foot-long silver cutlass, as with his left hand he propelled himself mightily forward, like a giant single-flippered fish, his bald head cutting through the water like a bullet, his beard tucked inside the helmet. He swam unerringly towards a gigantic green-grey walrus, which by its size and regal purple-orange crest seemed to be as the leader of the fish army.

As the thousands of terrified residents of Sub-Station Beta watched wide-eyed, Sir John raised the cutlass with a wild expression and descended furiously upon the bull walrus. Sir John cut a deep, angry gash in the thick flank of the bull, which reared back angrily and turned its tusks upon the old adventurer. They exchanged blows—One! Two! Three!—as inside the cracked Dome the citizens of the Station ooh’ed and ahh’ed, and outside it the fish legions stared at their leader with glassy eyes.

Thrust! Thrust! Parry! Sir John danced backwards in the water from the thrusting tusks of the beast. And then, with a surge of maniacal energy, he plunged his cutlass deep into the front lobe of the walrus’s skull. Thick black blood gushed from the hole, like ocean-spray spurting from the devil’s own blowhole.

The remaining fish seemed to hesitate—unwilling, perhaps, to resume their assault upon the Sub-Station if their champion was dead. Elinor allowed herself a sigh of relief. “Can it be?” she murmured to Marianne. “Are we saved?” Unconsciously, her eyes swept the crowds for some sign of Edward; to see confidence in his eyes would be her surest, her most encouraging sign.

But then, with one last furious, dying burst of energy, the bull walrus launched his shaggy head and protruding tusks back again towards Sir John. The beast missed him by the slimmest of margins, and his huge, thick head instead crashed into the Dome—causing a horrible, impossibly loud crack that echoed through the Sub-Station.

Then there was silence. In that queer long stretch of silence—which could not, in truth, have lasted more than a split second—the many thousands of people crowded in the central canals of Sub-Marine Station Beta, staring wide-eyed up at their now-crumbling protective shell, understood what was about to occur; and could at last, and too late, fully comprehend what it meant that they had made their home four miles below the surface of the ocean.

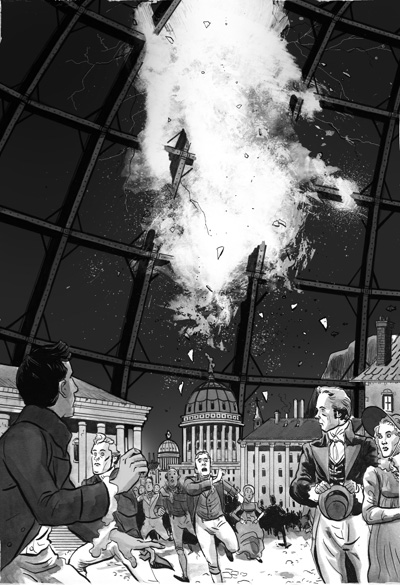

And then the silence ended, and glass tumbled in great jagged chunks from the roof of the Dome, and the water rushed in.

Once it began, the Dome gave way quickly, with sheets of glass heaving end over end to the ground, followed by waves of water rushing in from all directions; by walls of water pouring in from above; by great torrents of water crashing down like the wrath of God.

“Activate!” cried Elinor to Marianne, who looked about helplessly as the water buffeted them angrily about and bore them upwards. “Activate your Float-Suit!” With the same desperate motion, the girls tugged on the cords tucked up within their sleeves, and felt their twin armbands inflate and the nasal reeds begin to pump oxygen; and not a moment too soon, for in a matter of seconds the great glass Dome was in ruins, and they were underwater. The girls kicked their legs furiously and propelled themselves upwards as swiftly as they could, as all around them the world was subsumed.

* * *

“Ten . . . ten minutes to departure . . .”

The voice was that of a servant, walking the long echoing corridors of the Ascension Station, where Marianne, Elinor, and Mrs. Jennings sat, huddled in towels, awaiting the departure of Emergency Ferry No. 12.

THE DOME GAVE WAY QUICKLY, WITH SHEETS OF GLASS TUMBLING AND SLICING TO THE GROUND, FOLLOWED BY WAVES OF WATER RUSHING IN FROM ALL DIRECTIONS.

Sub-Station Beta had been reclaimed by the ocean. All that remained was the Ascension Station, the gigantic plain white waiting room, at the base of the long stovepipe that had once jutted proudly from the lip of the Dome; and soon the Ascension Station, too, would be abandoned, once all surviving residents were boarded onto emergency ferries and evacuated to safety. All around Elinor, hundreds of people sat in miserable small crowds, shivering and waterlogged, wondering whether friends and loved ones had survived, largely presuming they had not. Many had been drowned as the great waves crashed in, many had been eaten by the fish who swarmed giddily in, and many had been drowned and then eaten, or vice versa.

Elinor stared out the glass window of the Ascension Station and watched as the crew of gigantic monster lobsters, whom she had seen wreak such havoc that night at Hydra-Z, swam happily by; they were joined in their flotilla by a flight of swordfish, and Elinor swore she saw among the group the one with a gleaming patch of silver iridescence under its horn—the very fish that had led the tapping pack on Mrs. Jennings’s docking station.

This unsettling reverie was interrupted by the sudden appearance of Lucy Steele, who, alone among the miserable survivors awaiting emergency Ascension, seemed perfectly content—the destruction of the Station, after all, did not affect her newly decided prospects. Her own happiness, and her own spirits, were at least very certain; and she joined Mrs. Jennings most heartily in her expectation of their being all comfortably together in Delaford before long. She openly declared that no exertion for their good on Miss Dashwood’s part, either present or future, would ever surprise her, for she believed her capable of doing anything in the world for those she really valued.

“Yes, yes,” replied Elinor; this was the last topic of conversation she felt interested in discussing at such a moment.

“Nine . . . nine minutes to departure . . .”

As for Colonel Brandon, Lucy was not only ready to worship him as a saint, but was moreover truly anxious that he should be treated as one in all worldly concerns; anxious that his tithes should be raised to the utmost; and scarcely resolved to avail herself, at Delaford, as far as she possibly could, of his servants, his carriage, his cows, and his poultry.

“Yes, yes,” said Mrs. Jennings, “Understood.”

Lucy, finding the others less enthusiastic about pondering her happy future than she was, left to find her sister, who she had last seen desperately struggling to engage her Float-Suit. Elinor’s gladness at her departure lasted until the arrival of John Dashwood, whose recent experiences in the service of the Sub-Station laboratories had served him in good stead in the catastrophe, particular the prodigious swimming ability lent to him by his webbed toes and begilled lungs.

“Eight . . . eight minutes . . .”

“I am not sorry to see you alone,” he said to Elinor, “for I have a good deal to say to you.”

“Do not fear, brother—I have survived the wreck of the Sub-Station, as has Marianne. Margaret and our mother, as you know, are safe at home on Pestilent Island and so were spared this ungodly calamity.” Even as she said the words, Elinor recalled the distressing news of Margaret she had had in her mother’s last missive, and she silently fingered the torn patch of thin paper, with its grim Biblical quotation, still tucked inside her bodice and miraculously (or was it ominously?) preserved in the flood.

“Oh, yes, yes, that,” said Mr. Dashwood dismissively. As always, financial matters, for him, trumped all considerations, even the destruction of the foremost British city by an army of all-destroying fish. “This lighthouse provided by Colonel Brandon’s—can it be true? Has he really given it to Edward? I was coming to you on purpose to enquire further about it when all of this began.”

“It is perfectly true. Colonel Brandon has given the lighthouse at Delaford to Edward.”

“Really! Well, this is very astonishing! No relationship! No connection between them! And now that lighthouse posts fetch such a price! What was the value of this?”

“It is truly astonishing!” he cried, after hearing what she said. “What could be the colonel’s motive?”

“A very simple one—to be of use to Mr. Ferrars.”

“Well, well; whatever Colonel Brandon may be, Edward is a very lucky man. You will not mention the matter to Fanny, however, for though I have broke it to her, and she bears it vastly well, she will not like to hear it much talked of. If she survived all this, of course,” he added, a shadow of distress passing over his face. “You haven’t seen her, have you? No? Ah, well.”

“Seven. . . . Gather your belongings, if any you may still possess.”

“Mrs. Ferrars,” added Mr. Dashwood, lowering his voice so as not to be heard by the white-coated ferry servant counting down the minutes to the emergency ferry’s Ascension, “knows nothing about it at present, and I believe it will be best to keep it entirely concealed from her as long as may be. When the marriage takes place, I fear she must hear of it all.

“My God!” Elinor replied. “Can such an elderly personage have survived this calamity?”

“Indeed,” he answered. “I saw her with my own eyes; her Float-Suit engaged and she kicked with a strength quite startling in someone of her advanced age.” Elinor reflected that someone who took such evident displeasure in all aspects of life should fight so stubbornly against death.

“It is doubtless, Elinor,” John continued, “that when Edward’s unhappy match takes place, depend upon it, his mother will feel as much as if she had never discarded him; and, therefore, every circumstance that may accelerate that dreadful event, must be concealed from her as much as possible. Mrs. Ferrars can never forget that Edward is her son.”

“You surprise me. I should think it must nearly have escaped her memory by this time.”

“Six . . .”

“You wrong her exceedingly. Mrs. Ferrars is one of the most affectionate mothers in the world.”

Elinor was silent.

“We think now,” said Mr. Dashwood, after a short pause, “of Robert’s marrying Miss Morton. If, that is, Robert has survived, and Miss Morton has survived.” For a moment, John and Elinor hung their heads in silence, as the overwhelming nature of this great tragedy struck them like a blow. So much death—so much destruction.

Elinor at last summoned the fortitude to calmly reply, “The lady, I suppose, has no choice in the affair.”

“Choice!—how do you mean?”

“Five minutes,” called the servant, “All aboard . . . all aboard for emergency Ascension . . .”

They continued their conversation as they climbed aboard the Emergency Ferry, a one-hundred-foot iron-hulled submarine with a vast interior cabin, wide as a cow-pasture, lined with uncomfortable, utilitarian wooden benches.

“I only mean that I suppose,” Eleanor continued as they squeezed into spots, “from your manner of speaking, it must be the same to Miss Morton whether she marry Edward or Robert.”

“Certainly, there can be no difference; for Robert will now to all intents and purposes be considered as the eldest son; and as to anything else, they are both very agreeable young men: I do not know that one is superior to the other.”

Elinor said no more, and John was also for a short time silent; they felt the powerful engines of the submarine engage, and Elinor breathed an interior sigh of relief that the vessel hadn’t been sabotaged by sea monsters, or simply waterlogged in the catastrophe.

“Of one thing, my dear sister,” John said, kindly taking her hand, and speaking in an awful whisper, “I have good reason to think—indeed I have it from the best authority, or I should not repeat it, for otherwise it would be very wrong to say anything about it—”

“Four minutes!”

“You best summon the ability to reveal it, dear brother.”

“I have it from the very best authority—not that I ever precisely heard Mrs. Ferrars say it herself—but her daughter did, and I have it from her—that in short, whatever objections there might be against a certain— a certain connection—you understand me—it would have been far preferable to her, it would not have given her half the vexation that this does. But however, all that is quite out of the question—not to be thought of or mentioned—as to any attachment you know—it never could be— all that is gone by. But I thought I would just tell you of this, because I knew how much it must please you. Not that you have any reason to regret, my dear Elinor. There is no doubt of your doing exceedingly well. Has Colonel Brandon been with you lately?”

Elinor had heard enough to agitate her nerves and fill her mind, and she was glad to be distracted by the powerful sensation of the submarine’s thruster-propellers whirring to life beneath the vast hull. She was spared from the necessity of saying much in reply herself, and from the danger of hearing anything more from her brother, by the entrance of Mr. Robert Ferrars, panting and out of breath, lugging an oversized wooden trunk on his back like a mule.

“I made it!” he cheered gaily. “By God I made it, and barely nicked the good china along the way!”

“Three . . .” came the voice of the servant, and it was instantly echoed by the voice of the captain, hollering along the long cabin of the submarine. “Three minutes to Ascension.”

“Three! My God!” hollered John Dashwood, and hastened away to make a last-minute search for Fanny and their child. Elinor was left to improve her acquaintance with Robert, who, by the happy self-complacency of his manner on this most desperate of occasions, was confirming her most unfavourable opinion of his head and heart.

As he buckled himself in to an adjoining ferry bench, Robert promptly began to speak of Edward; for he, too, had heard of the posting at the Delaford lighthouse, and was very inquisitive on the subject. Elinor repeated the particulars of it, as she had given them to John; and their affect on Robert, though very different, was not less striking than it had been on him. He laughed most immoderately. The idea of Edward’s being a mere lighthouse keeper, and tracking the movements of some second-rate Loch Ness Monster, diverted him beyond measure; he could conceive nothing more ridiculous.

“Two minutes!”

Elinor, even as she gritted her teeth and prepared for the lurching motion of the great submarine’s departure, could not restrain her eyes from being fixed on Robert with a look that spoke all the contempt it excited.

“We may treat it as a joke,” said he, at last, recovering from the affected laugh which had considerably lengthened out the genuine gaiety of the moment—”but, upon my soul, it is a most serious business. Poor Edward! He is ruined forever. I am extremely sorry for it—for I know him to be a very good-hearted creature. You must not judge of him, Miss Dashwood, from your slight acquaintance. Poor Edward! His manners are certainly not the happiest in nature. But we are not all born, you know, with the same powers. Poor fellow!—to see him in a circle of strangers!— among lake people! But upon my soul, I believe he has as good a heart as any in the kingdom; and I declare and protest to you I never was so shocked in my life, as when it all burst forth. My mother was the first person who told me of it; and I, feeling myself called on to act with resolution, immediately said to her, ‘My dear madam, I do not know what you may intend to do on the occasion, but as for myself, I must say, that if Edward does marry this young woman, I never will see him again.’ Poor Edward! He has done for himself completely, shut himself out for ever from all decent society! But, as I directly said to my mother, I am not in the least surprised at it; from his style of education, it was always to be expected. My poor mother was half frantic.”

Unmoved by this appeal to empathy for Mrs. Ferrars, and indeed weary of the whole line of conversation, Elinor happened to look outside the window of the Ferry, where a universe of fish now swam and darted happily through the ruins of the elaborate civilization that had been built on their turf. She happened to spy, as she looked disconsolately at the wreck of the Sub-Station, a small, cigar-shaped one-person submarine of an old-fashioned design, whooshing rapidly by in a spray of bubbles. Behind the wheel was Lady Middleton, who—for the first time since she had made that worthy’s acquaintance—was smiling; indeed, grinning from ear to ear, and, or so Elinor thought, whooping loudly with pleasure.

Recovering herself from this remarkable sight, Elinor rejoined her conversation with Robert Ferrars. “Have you ever seen Edward’s intended?” she asked.

“Yes; once, while she was staying in our house, I happened to drop in for ten minutes; and I saw quite enough of her. The merest awkward country girl, without style, or elegance, and almost without beauty. Just the kind of girl I should suppose likely to captivate poor Edward. I offered immediately, as soon as my mother related the affair to me, to talk to him myself, and dissuade him from the match; but it was too late then, I found, to do anything. But had I been informed of it a few hours earlier—I think it is most probable—that something might have been hit on. I certainly should have represented it to Edward in a very strong light. ‘My dear fellow, you are making a most disgraceful connection, and such a one as your family are unanimous in disapproving.’ But now it is all too late. He must be starved, you know—that is certain; absolutely starved. He would have been better off, if he lived through what has just occurred, to have drowned instead.”

Elinor thought she could bear no more of this, when the grave voice of the public address reached its conclusion.

“ONE . . . be braced . . .”

And the turbines revved up to their full capacity, and the propellers whirred faster, and the seat rumbled beneath her as the Ascension Station discharged the emergency ferry, with all its passengers aboard; Elinor looked around, and saw that, two benches over, Marianne was looking out the window of the ferry with the same sentimental regard she looked upon all places, at all times, on leaving them—no matter what level of affection she may have bore during her time there. On this occasion, however, Elinor shared in her moist-eyed regard.

Sub-Marine Station Beta was no more.