CHAPTER 19

EDWARD REMAINED ONLY A WEEK at the rickety shanty perched high above Barton Cove; as if he were bent only on self-mortification, he seemed resolved to be gone when his enjoyment among his friends was at the height. His spirits, during the last two or three days, were greatly improved—he grew more and more partial to the house and environs—never spoke of going away without a sigh—declared his time to be wholly disengaged—spoke of his fear of climbing back aboard a sailing ship and trusting his fate to the tides—but still, go he must. Never had any week passed so quickly—he could hardly believe it to be gone. He said so repeatedly; other things he said too, which marked the turn of his feelings and gave the lie to his actions. He had no pleasure at Norland; he detested being in-Station; but either to Norland or Sub-Marine Station Beta, he must go. He valued their kindness beyond anything, and his greatest happiness was in being with them. Yet, he must leave them at the end of a week, in spite of their wishes and his own, and without any restraint on his time.

Elinor placed all that was astonishing in this way of acting to his mother’s account; she rejected all suggestion from her mother that a pirate-ghost was again responsible for the ambiguities in their guest’s behaviour. His want of spirits, openness, and consistency, were attributed to his want of independence, and his better knowledge of Mrs. Ferrars’s disposition and designs. The shortness of his visit, the steadiness of his purpose in leaving them, originated in the same fettered inclination, the same inevitable necessity of temporizing with his mother. The old well-established grievance of duty against will, parent against child, was the cause of all.

“I think, Edward,” said Mrs. Dashwood, as they stood upon the rickety dock the last morning, where she, desirous of an opportunity for intimate conversation, had enticed him to join her in her habitual morning quarter-hour of spear fishing. “You would be a happier man if you had any profession to engage your time. Some inconvenience to your friends might result from it—you would not be able to give them so much of your time. But you would know where to go when you left them.”

“I do assure you,” he replied, heaving his pike into the water and— since it was attached to his wrist by a long length of cable—bracing himself so he was not tugged in after it, “that I have long thought on this point, as you think now. It has been, and probably will always be a heavy misfortune to me, that I have no necessary business to engage me or afford me anything like independence. But unfortunately my own nicety, and the nicety of my friends, have made me what I am: an idle, helpless being; isolated with my scholarly tomes and my theory of the Alteration. We never could agree in our choice of a profession. I always imagined myself a lighthouse keeper, as I still do. A quiet room atop an observation post, shining my beacon light when required, otherwise satisfied in the company of my books and my thoughts. But that was not smart enough for my family.” With a sigh he reeled back in his spear with no pierced specimen caught upon it, and a wry chuckle escaped him. “I suppose we may add fish-slayer to the list of professions to which I am unsuited.”

“Come, come; this is all an effusion of immediate want of spirits, Edward. You are in a melancholy humour, and fancy that anyone unlike yourself must be happy. Oof!” With a grunt, Mrs. Dashwood retrieved her own pike, upon which was impaled a perfect specimen of tuna. “But remember that the pain of parting from friends will be felt by everybody at times, whatever be their education or state. Know your own happiness. You want nothing but patience. Your mother will secure to you, in time, that independence you are so anxious for. How much may not a few months do?”

“I think,” replied Edward, “that I may defy many months to produce any good to me.” He tossed his spear idly from hand to hand, as if considering whether to plunge it into his breast rather than back into the blue-black depths where it could not hope to find its target.

But before any such drastic measure could be undertaken, a tuna the size of a man slammed its broadside against the leg of the dock. The waterlogged wood gave way with a muffled splintering crack, plunging both Mrs. Dashwood and Edward into the churning water.

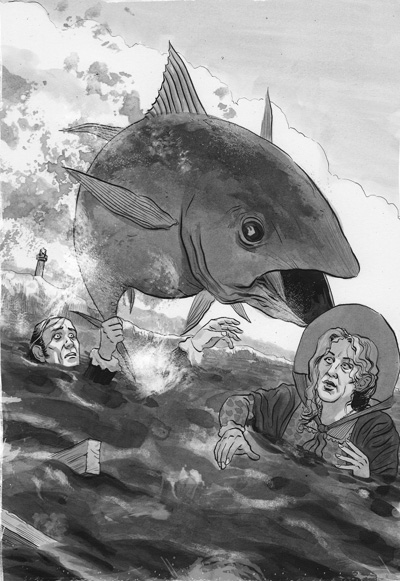

Gasping, Edward gallantly sought to interpose himself between his hostess and the six-foot-long, broad-flanked tuna, but to no avail; it nosed Edward aside with a mighty shove, and bore down on Mrs. Dashwood, who was finding it hard to stay afloat in her empire dress and girdle. Apart from its sheer girth, their foe bore an unmistakable glimmer in its eyes, impossible to mistake for mere fish-hunger—Mrs. Dashwood had murdered his companion, and this tuna was intent upon revenge. Edward sought to grapple with the rear quarters of the great fish but its tail slipped from his grasp, whilst it opened his massive wet maw around Mrs. Dashwood’s head, hoping, it seemed, to dispense with biting and swallow her whole.

Mrs. Dashwood, not ready to join her husband in Heaven, nor in the stomach of an ocean-dwelling monstrosity, managed to recover from her décolletage a long sewing needle, razor sharp, which she had secreted there after sewing a replacement stitch in Marianne’s party gown that morning. Just as the tuna’s sickening mouth was about to close around her forehead, she withdrew the needle and drove it into the palate of the beast.

With surprise and indignation the tuna thrashed, trying to untwist itself from the sewing needle, while Mrs. Dashwood let go and doggy-paddled her way towards the dock-pillar that remained standing. Edward, seeing his chance to aid in the overcoming of their attacker, took a deep breath and swam under the body of the beast; emerging suddenly above the water line directly in front of it. In a paroxysm of fury and pain from the sewing needle impaled in its mouth, the tuna now drove its giant head crashing into Edward’s chest, knocking him backwards and sending the breath sputtering from his body. Disappearing beneath the surface, his mouth filling with salty water, Edward was suddenly faced with the prospect that his melancholy, death-embracing spirits might find their consummation sooner than he had wished.

EDWARD SOUGHT TO GRAPPLE WITH THE REAR QUARTERS OF THE GREAT FISH WHILST IT OPENED ITS MASSIVE WET MAW AROUND MRS. DASHWOOD’S HEAD.

As Edward sank, the tuna slammed the broad side of its long, flat head against his skull; he spun in the water, noting with the numb, half-seeing eyes of a drowning man where the piles were submerged in the sea floor. The fish battered away at him, intent (or so it seemed) on beating him to death before consuming him. Edward thought of Elinor. He had no hope left, no means of counter-attack—no weapon but his own hands.

With a burst of vigor, Edward kicked his feet and sent himself hurtling upwards at the tuna; he knew from his conversations with the wise Elinor that there was but one perfect place to assault a sea-breathing creature from below: the gills. Grasping the surprised fish on either side of its broad face, Edward tore at its fleshy slitted openings, clawing and scraping, plunging in his fingers mercilessly and gouging out great oozing hunks of fish flesh. He pulled himself face to face with the beast, his eyes bulging from oxygen loss, staring into the cold eyes of the fish— which also bulged from the shock and pain of Edward’s assault. He dug deeper, his fingernails crawling inside the face of the tuna, until its wild thrashing suddenly ceased; its eyes turned from cruel and cold to glassy and dead.

A moment later Edward emerged, gasping, and slowly swam to shore.

Meanwhile, Elinor was in her room on the second floor of Barton Cottage, midway through getting dressed, bent over double and clutching her temples; it was again the five-pointed figure which had engendered her agony. What she did not know—nor how could she?—was that the moment it appeared again in her mind, crowding out all thought and filling her body with the most exquisite, searing pain, was the very instant of Edward’s most extreme peril.

Shortly after delivering a wet and discomfited Mrs. Dashwood back to the house, Edward departed, still very much in a desponding turn of mind. This despondence gave additional pain to all in the parting and left an uncomfortable impression on Elinor’s feelings especially, which required some trouble and time to subdue. But as it was her determination to prevent herself from appearing to suffer more than the rest of her family on his going away, she did not adopt the method of embracing solitude so judiciously employed by Marianne, on a similar occasion. She did not shut herself in her room with tales of hunger-maddened sailors, nor moan the verses of ancient shanties and shake and sigh. Their means of despondence were as different as their objects, and equally suited to the advancement of each.

Elinor sat down to her driftwood-whittling table as soon as he was out of the house and busily employed herself the whole day, steadily transforming a fresh bucket of wood into a parade of winged cherubs. She neither sought nor avoided the mention of his name and appeared to interest herself almost as much as ever in the general concerns of the family. Inside, her mind was alive with questions—as to Edward’s conduct, as to her own affection, and as to the curious and discomfiting hallucination, if such it was, that continued to plague her. But such considerations were alive only in her own mind, and never in conversation; if, by this conduct, she did not lessen her own grief, it was at least prevented from unnecessary increase, and her mother and sisters were spared much solicitude on her account.

Without shutting herself up from her family, or leaving the house in determined solitude to avoid them, or lying awake the whole night to indulge meditation, Elinor found every day afforded her leisure enough to think of Edward, and of Edward’s behaviour, in a variety of lights—with tenderness, pity, approbation, censure, and doubt.

When she was roused one morning, by the arrival of company, Elinor happened to be quite alone. The creak of the rickety wooden staircase drew her eyes to the window, and she saw a large party walking up to the door. Amongst them were Sir John and Lady Middleton and Mrs. Jennings, but there were two others, a gentleman and lady, who were quite unknown to her. She was sitting near the window, and as soon as Sir John perceived her, he left the rest of the party to the ceremony of knocking at the door and, vaulting over his cane in a fluid motion onto the porch, obliged her to speak to him.

“Well,” said he, “we have brought you some strangers. How do you like them?”

“Hush! They will hear you.”

“Never mind if they do. It is only the Palmers. Charlotte is very pretty, I can tell you. You may see her if you look this way.”

As Elinor was certain of seeing her in a couple of minutes, without taking that liberty, she begged to be excused.

“Where is Marianne? Has she run away because we are come?”

“She is walking the beach, I believe.”

“I do hope she is careful. I noticed a distinct trail of slime along the cove as we rowed in; very likely further evidence of the Fang-Beast.”

“Pardon me?”

But they were now joined by Mrs. Jennings, who had not patience enough to wait till the door was opened before she told her story. She came hallooing to the window, “How do you do, my dear? How does Mrs. Dashwood do? And where are your sisters? What! All alone! You will be glad of a little company to sit with you. I have brought my daughter and her husband to see you. Only think of their coming so suddenly! I thought I heard a canoe or a clipper ship last night, while we were drinking our tea, but it never entered my head that it could be them. I thought of nothing but whether it might not be Colonel Brandon come back again; so I said to Sir John, I do think I hear a canoe being tied up against the dock. Perhaps it is Colonel Brandon come back again—”

Elinor was obliged to turn from her, in the middle of her prattling, to receive the rest of the party; Lady Middleton introduced the two strangers; Mrs. Dashwood and Margaret came down stairs at the same time, and they all sat down to look at one another.

Mrs. Palmer was Lady Middleton’s younger sister; she, too, been abducted at machete-point by Sir John and his hunting party; short and plump, she had gone as prize to Mr. Palmer, Sir John’s right-hand man on that particular expedition. Several years younger than Lady Middleton, she was totally unlike her in every respect; she had a very pretty face, and the finest expression of good humour. Her attitude had none of the simmering resentment of her sister’s, and one never received the impression from her, as one did on occasion from Lady Middleton, that given the right opportunity she would slit the throats of all present and decamp to her native country. She came in with a smile, and smiled all the time of her visit, except when she laughed. Her husband was grave-looking, with an air of more fashion and sense than his wife, but of less willingness to please or be pleased. Clad in the hunting boots and battered hunting cap of the ex-adventurer he was, he entered the room with a look of self-consequence, slightly bowed to the ladies, without speaking a word, and, after briefly surveying them and their apartments, took up a newspaper from the table, and continued to read it as long as he stayed.

“Mr. Palmer,” said Sir John quietly to Elinor, by way of explanation, “has a certain unwholesome frame of mind. There are men, such as myself, who set off to see the world and return with an animated spirit, pleased with the things they have known and seen. Others—there are others who return with the darkness upon them.”

Mrs. Palmer, on the contrary, was strongly endowed by nature with a turn for being uniformly civil and happy. “Well! What a delightful room this is! I never saw anything so charming! How I should like such a place for myself! Should not you, Mr. Palmer?”

Mr. Palmer made her no answer, and did not even raise his eyes from the newspaper.

“Mr. Palmer does not hear me,” said she, laughing. “He never does sometimes. It is so ridiculous!”

This was quite a new idea to Mrs. Dashwood; she had never found wit in the inattention of anyone, and could not help looking with surprise at them both.

Mrs. Jennings, in the meantime, talked on as loud as she could and continued her account of their surprise the evening before on seeing their family, without ceasing till everything was told. Mrs. Palmer laughed heartily at the recollection of their astonishment, and everybody agreed, two or three times over, that it had been quite an agreeable surprise.

“You may believe how glad we all were to see them,” added Mrs. Jennings, leaning forward towards Elinor, and speaking in a low voice as if she meant to be heard by no one else, though they were seated on different sides of the room; “but I can’t help wishing they had not travelled quite so fast, nor made such a long journey of it, for they came all round by Sub-Marine Station Beta upon account of some business, for you know (nodding significantly and pointing to her daughter) it was wrong in her situation. I wanted her to stay at home and rest this morning, but she would come with us; she longed so much to see you all!”

Mrs. Palmer laughed, and said it would not do her any harm.

“She expects to be confined in February,” continued Mrs. Jennings.

Lady Middleton could no longer endure such a conversation, and therefore exerted herself to ask Mr. Palmer if there was any news in the paper.

“Whaler eaten by whale. Crew all dead,” he replied curtly, and read on.

“Here comes Marianne,” cried Sir John. “Now, Palmer, you shall see a monstrous pretty girl.” Mr. Palmer did not look up, but rather turned the page of his newspaper slowly, communicating thereby that the very idea of prettiness in a girl was trivial in the extreme, when set against the great masses of un-prettiness of which the world was in essence comprised.

Sir John grabbed his cane and went into the passage, opened the front door, and ushered her in himself. Mrs. Jennings asked her, as soon as she appeared, if she had not been to Allenham Isle; and Mrs. Palmer laughed so heartily at the question, as to show she understood it. Mrs. Palmer’s eye was now caught by the driftwood sculpture of Buckingham Palace which decorated the sideboard. She got up to examine it.

“Oh! How well carved that is! Do but look, Mama, how sweet! I declare it is quite charming; I could look at it for ever.” And then sitting down again, she very soon forgot that there was any such thing in the room, even though the driftwood palace smelled unpleasantly of the algae that still clung to it.

When Lady Middleton rose to go away, Mr. Palmer rose also, laid down the newspaper, stretched himself and looked at them all around.

“My love, have you been asleep?” said his wife, laughing.

He made her no answer; and only observed, after again examining the room, that it was very low pitched, and that the ceiling was crooked. He then made his bow, sighed heavily, and departed with the rest.

Sir John had been very urgent with them all to spend the next day on Deadwind Island. Mrs. Dashwood, who did not choose to dine with them oftener than they dined at the cottage, absolutely refused on her own account; her daughters might do as they pleased. But they had no curiosity to see how Mr. and Mrs. Palmer ate their dinner, and no expectation of pleasure from them in any other way. They attempted therefore to excuse themselves also; the weather was uncertain, the fog so thick as to be virtually impassable. But Sir John would not be satisfied—his yacht, with fog-cutters attached, should be sent for them and they must come. Mrs. Jennings and Mrs. Palmer joined their entreaties, and the young ladies were obliged to yield.

“Why should they ask us?” said Marianne, as soon as they were gone. “The rent of this shanty is low; but we have it on very hard terms, if we are to dine on Deadwind Island whenever anyone is staying either with them, or with us.”

“They mean no less to be civil and kind to us now,” said Elinor, hands busy once more with a new hunk of driftwood, which she intended to shape into Henry VIII. “The difference is not in them, if their parties are grown tedious and dull. We must look for the change elsewhere.”