DE ROQUEFORT SAT IN THE PASSENGER SEAT AND CONCENTRATED on the GPS screen. The transponder attached to Malone’s rental car was working perfectly, the tracking signal transmitting strongly. One brother drove while Claridon and another brother occupied the rear seat. De Roquefort was still irritated with Claridon’s interference back in Rennes. He had no intention of dying and would have eventually leaped out of the way, but he’d truly wanted to see if Cotton Malone possessed the resolve to drive through him.

The brother who’d fallen down the rocky incline had died, shot in the chest before he fell. A Kevlar vest had prevented the bullet from doing any damage, but the fall had broken the man’s neck. Thankfully, none of them carried identification, but the vest was a problem. Equipment like that signaled sophistication, but nothing linked the dead man to the abbey. All the brothers knew Rule. If any of them were killed outside the abbey, their bodies would go unidentified. Like the brother who’d leaped from the Round Tower, Renne’s casualty would end up in a regional morgue, his remains eventually consigned to a pauper’s grave. But before that happened, procedure called for the master to dispatch a clergyman, who would claim the remains in the name of the Church, offering to provide a Christian burial at no cost to the state. Never had that offer been refused. And while arousing no suspicion, the gesture ensured that a brother received his proper internment.

He’d not rushed leaving Rennes, first searching Lars Nelle’s and Ernst Scoville’s houses and finding nothing. His men had reported that Geoffrey had carried a rucksack, which was handed over to Mark Nelle in the car park. Surely it contained the two stolen books.

“Any idea where they went?” Claridon asked from the backseat.

He pointed to the screen. “We’ll know shortly.”

After questioning the injured brother who’d eavesdropped on Claridon’s conversation inside Lars Nelle’s house, he’d learned that Geoffrey had said precious little, obviously suspicious of Claridon’s motivations. Sending Claridon in there had been a mistake. “You assured me you could find those books.”

“Why do we need them? We have the journal. We should be concentrating on deciphering what we have.”

Maybe, but it bothered him that Mark Nelle had chosen those two volumes from the thousands in the archives. “What if they contain information different from the journal?”

“Do you know how many versions of the same information I’ve come across? The entire Rennes story is a series of contradictions stacked atop one another. Let me explore your archives. Tell me what you know and let’s see what, together, we have.”

A good idea, but unfortunately—contrary to what he’d led the Order to believe—he knew precious little. He’d been counting on the master leaving the requisite message for his successor, in which the most coveted information was always passed from leader to leader, as had been done from the time of de Molay. “You’ll get that opportunity. But first we must take care of this.”

He thought again of the two dead brothers. Their deaths would be seen by the collective as an omen. For a religious society heaped in discipline, the Order was astoundingly superstitious. And violent death was not common—yet two had occurred in a matter of days. His leadership could now well be questioned. Too much, too fast would be the cry. And he’d be forced to listen to all objections since he’d openly challenged the last master’s legacy, in part because that man had ignored the brothers’ wishes.

He asked the driver for an interpretation of the GPS readout. “How far to their vehicle?”

“Twelve kilometers.”

He gazed out beyond the car windows at the French countryside. Once, no stretch of sky had been true to the eye unless a tower rose on the horizon. By the twelfth century Templars had populated this land with well over a third of their total estates. The entire Languedoc should have become a Templar state. He’d read of plans in the Chronicles. How fortresses, outposts, supply depots, farms, and monasteries had all been strategically established, each connected by a series of maintained roads. For two hundred years the brotherhood’s strength had been carefully preserved, and when the Order failed to establish a fiefdom in the Holy Land, eventually surrendering Jerusalem back to the Muslims, the aim had been to succeed in the Languedoc. All was well under way when Philip IV struck his death blow. Interestingly, Rennes-le-Château was never mentioned in the Chronicles. The town, in all of its previous incarnations, played no role in Templar history. There’d been Templar fortifications in other parts of the Aude Valley, but nothing at Rhedae, as the occupied summit was then called. Yet now the tiny village seemed an epicenter, and all because of an ambitious priest and an inquisitive American academician.

“We’re approaching the car,” the driver said.

He’d already instructed caution. The other three brothers he’d brought to Rennes were returning to the abbey, one with a flesh wound to his thigh after Geoffrey shot at him. That made three wounded men, along with two dead. He’d sent word that he wanted a council with his officers when he returned to the abbey, which should quell any discontent, but first he needed to know where his quarry had gone.

“Up ahead,” the driver said. “Fifty meters.”

He stared out the window and wondered about Malone and company’s choice of refuge. Odd that they would come here.

The driver stopped the car, and they climbed out.

Parked cars surrounded them.

“Bring the handheld unit.”

They walked and, twenty meters later, the man holding the portable receiver stopped. “Here.”

De Roquefort stared at the vehicle. “That’s not the car they left Rennes in.”

“The signal is strong.”

He motioned. The other brother searched beneath and found the magnetic transponder.

He shook his head and stared at the walls of Carcassonne, which stretched skyward ten meters away. The grassy area before him had once formed the town moat. Now it served as a car park for the thousands of visitors who came each day to see one of the last existing walled cities from the Middle Ages. The time-tanned stones had stood when Templars roamed the surrounding land. They’d borne witness to the Albigensian Crusade and the many wars thereafter. And never once were they breached—truly a monument to strength.

But they said something about cleverness, too.

He knew the local myth, from when Muslims controlled the town for a short time in the eighth century. Eventually, Franks came from the north to reclaim the site and, true to their way, laid a long siege. During a sally the Moorish king was killed, which left the task of defending the walls to his daughter. She was the clever one, creating an illusion of greater numbers by sending the few troops she possessed running from tower to tower and stuffing the clothing of the dead with straw. Food and water eventually ran out for both sides. Finally, the daughter ordered the last sow be caught and fed the final bushel of corn. She then hurled the pig out over the walls. The animal smashed into the earth and its belly burst forth with grain. The Franks were shocked. After such a long siege, apparently the infidels still possessed enough food to feed their pigs. So they withdrew.

A myth, he was sure, but an interesting tale of ingenuity.

And Cotton Malone had shown ingenuity, too, transferring the electronic tag to another vehicle.

“What is it?” Claridon asked.

“We’ve been led astray.”

“This is not their car?”

“No, monsieur.” He turned and started back for their vehicle. Where had they gone? Then a thought occurred to him. He stopped. “Would Mark Nelle know of Cassiopeia Vitt?”

“Oui,” Claridon said. “He and his father discussed her.”

Is it possible that was where they’d gone? Vitt had interfered three times of late, and always on Malone’s side. Maybe he sensed an ally there.

“Come.” And he started for the car again.

“What do we do now?” Claridon wanted to know.

“We pray.”

Claridon still had not moved. “For what?”

“That my instincts are accurate.”

MALONE WAS FURIOUS. HENRIK THORVALDSEN HAD KNOWN FAR more about everything and had said absolutely nothing. He pointed at Cassiopeia. “She one of your friends?”

“I’ve known her a long time.”

“When Lars Nelle was alive. You know her then?”

Thorvaldsen nodded.

“And did Lars know of your relationship?”

“No.”

“So you played him for a fool, too.” Anger punctuated his voice.

The Dane seemed forced to submerge his defensiveness. After all, he was cornered. “Cotton, I understand your irritation. But one can’t always be forthcoming. Multiple angles have to be explored. I’m sure that when you worked for the U.S. government you did the same thing.”

He did not rise to the bait.

“Cassiopeia kept watch on Lars. He knew of her, and in his eyes, she was a nuisance. But her real chore was to protect him.”

“Why not just tell him?”

“Lars was a stubborn man. It was simpler for Cassiopeia to watch him quietly. Unfortunately, she could not protect him from himself.”

Stephanie stepped forward, her face set for combat. “This is what his profile warned about. Questionable motives, shifting allegiances, deceit.”

“I resent that.” Thorvaldsen glared at her. “Especially since Cassiopeia looked after you two, as well.”

On that point Malone could not argue. “You should have told us.”

“To what end? As I recall, you both were intent on coming to France—especially you, Stephanie. So what would have been gained? Instead, I made sure Cassiopeia was there, in case you needed her.”

Malone wasn’t going to accept that hollow explanation. “For one thing, Henrik, you could have provided us with background on Raymond de Roquefort, whom you both obviously know. Instead, we went in blind.”

“There’s little to tell,” Cassiopeia said. “When Lars was alive all the brothers did was watch him, too. I never made actual contact with de Roquefort. That’s only happened during the past couple of days. I know as much about him as you do.”

“Then how did you anticipate his moves in Copenhagen?”

“I didn’t. I simply followed you.”

“I never sensed you there.”

“I’m good at what I do.”

“You weren’t so good in Avignon. I spotted you at the café.”

“And your trick with the napkin, dropping it so you could see if I was following? I wanted you to know I was there. Once I saw Claridon, I knew de Roquefort would not be far behind. He’s watched Royce for years.”

“Claridon told us about you,” Malone said, “but he didn’t recognize you in Avignon.”

“He’s never seen me. What he knows is only what Lars Nelle told him.”

“Claridon never mentioned that fact,” Stephanie said.

“There’s a lot I’m sure Royce failed to mention. Lars never realized, but Claridon was far more of a problem for him than I ever was.”

“My father hated you,” Mark said, disdain in his tone.

Cassiopeia appraised him with a cool countenance. “Your father was a brilliant man, but he was not schooled in human nature. His was a simplistic view of the world. The conspiracies he sought, the ones you explored after he died, are far more complicated than either of you could imagine. This is a quest for knowledge that men have died seeking.”

“Mark,” Thorvaldsen said, “what Cassiopeia says about your father is true, as I’m sure you realize.”

“He was a good man who believed in what he did.”

“He was, indeed. But he likewise kept many things to himself. You never knew he and I were close friends, and I regret you and I never came to know one another. But your father wanted our contacts confidential, and I respected his desire even after his death.”

“You could have told me,” Stephanie said.

“No, I couldn’t.”

“Then why are you talking to us now?”

“When you and Cotton left Copenhagen, I came straight here. I realized you would eventually find Cassiopeia. That’s precisely why she was in Rennes two nights ago—to draw you in her direction. Originally, I was to stay in the background and you were not to know of our connection, but I changed my mind. This has gone too far. You need to know the truth, so I’m here to tell it to you.”

“So good of you,” Stephanie said.

Malone stared at the older man’s hooded eyes. Thorvaldsen was right. He’d played both ends against the middle many times. Stephanie had, too. “Henrik, I haven’t been a player in this kind of game in more than a year. I got out because I didn’t want to play anymore. Lousy rules, bad odds. But at the moment I’m hungry and, I have to say, curious. So let’s eat, and you tell us all about that truth we need to know.”

Lunch was a roasted rabbit seasoned with parsley, thyme, and marjoram, along with fresh asparagus, a salad, and a currant dessert topped with vanilla cream. While he ate, Malone tried to assess the situation. Their hostess seemed the most at ease, but he was unimpressed with her cordiality.

“You specifically challenged de Roquefort last night in the palace,” he said to her. “Where’d you learn your craft?”

“Self-taught. My father passed to me his boldness, and my mother blessed me with an insight into the male mind.”

Malone smiled. “One day you may guess wrong.”

“I’m glad you care about my future. Did you ever guess wrong as an American agent?”

“Many times, and folks died from it occasionally.”

“Henrik’s son on that list?”

He resented the jab, particularly considering she knew nothing of what happened. “Like here, people were given bad information. Bad information leads to bad decisions.”

“The young man died.”

“Cai Thorvaldsen was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Stephanie made clear.

“Cotton is right,” Henrik said as he stopped eating. “My son died because he was not alerted to the danger around him. Cotton was there and did what he could.”

“I didn’t mean to imply that he was to blame,” Cassiopeia said. “It was only that he seemed anxious to tell me how to run my business. I simply wondered if he could run his own. After all, he did quit.”

Thorvaldsen sighed. “You have to forgive her, Cotton. She’s brilliant, artistic, a cognoscenta in music, a collector of antiques. But she inherited her father’s lack of manners. Her mother, God rest her precious soul, was more refined.”

“Henrik fancies himself my surrogate father.”

“You’re lucky,” Malone said, scrutinizing her carefully, “that I didn’t shoot you off that motorcycle in Rennes.”

“I didn’t expect you to escape the Tour Magdala so quickly. I’m sure the domain operators are quite upset about the loss of that casement window. It was an original, I believe.”

“I’m waiting to hear that truth you spoke about,” Stephanie said to Thorvaldsen. “You asked me in Denmark to keep an open mind about you and what Lars thought important. Now we see that your involvement is far more than any of us realized. Surely, you can understand how we’d be suspicious.”

Thorvaldsen laid down his fork. “All right. What’s the extent of your knowledge about the New Testament?”

An odd question, Malone thought. But he knew Stephanie was a practicing Catholic.

“Among other things, it contains the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—which tell us about Jesus Christ.”

Thorvaldsen nodded. “History is clear that the New Testament, as we know it, was formulated during the first four centuries after Christ as a way to universalize the emerging Christian message. After all, that’s what catholic means—‘universal.’ Remember, unlike today, in the ancient world politics and religion were one and the same. As paganism declined, and Judaism retreated within itself, people began searching for something new. The followers of Jesus, who were merely Jews embracing a different perspective, formed their own version of the Word, but so did the Carpocratians, the Essenes, the Naassenes, the Gnostics, and a hundred other emerging sects. The main reason the Catholic version survived, while others faltered, was its ability to impose its belief universally. They grafted onto the Scriptures so much authority that eventually no one could question their validity without being deemed a heretic. But there are many problems with the New Testament.”

The Bible was a favorite of Malone’s. He’d read it and much historical analysis and knew all about its inconsistencies. Each Gospel was a murky mixture of fact, rumor, legend, and myth that had been subjected to countless translations, edits, and redactions.

“Remember, the emerging Christian Church existed in the Roman world,” Cassiopeia was saying. “In order to attract followers, the Church fathers had to compete not only with a variety of pagan beliefs, but also their own Jewish beliefs. They also needed to set themselves apart. Jesus had to be more than a mere prophet.”

Malone was becoming impatient. “What does this have to do with what’s happening here?”

“Think what finding the bones of Christ would mean for Christianity,” Cassiopeia said. “That religion revolves around Christ dying on the cross, resurrecting, and ascending into heaven.”

“That belief is a matter of faith,” Geoffrey quietly said.

“He’s right,” Stephanie said. “Faith, not fact, defines it.”

Thorvaldsen shook his head. “Let’s remove that element from the equation for a moment, since faith also eliminates logic. Think about this. If a man named Jesus existed, how would the chroniclers of the New Testament know anything about His life? Just consider the language dilemma. The Old Testament was written in Hebrew. The New was penned in Greek, and any source materials, if they even existed, would have been in Aramaic. Then there’s the issue of the sources themselves.

“Matthew and Luke tell of Christ’s temptation in the wilderness, but Jesus was alone when that occurred. And Jesus’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane. Luke says He uttered it after leaving Peter, James, and John a stone’s throw away. When Jesus returned He found the disciples asleep and was immediately arrested, then crucified. There’s absolutely no mention of Jesus ever saying a word about the prayer in the garden or the temptation in the wilderness. Yet we know its every detail. How?

“All of the Gospels speak of the disciples fleeing at Jesus’s arrest—so none of them was there—yet detailed accounts of the crucifixion are recorded in all four. Where did these details come from? What the Roman soldiers did, what Pilate and Simon did. How would the Gospel writers know any of that? The faithful would say the information came from God’s inspiration. But the four Gospels, these so-called Words of God, conflict with each other far more than they agree. Why would God offer only confusion?”

“Maybe that’s not for us to question,” Stephanie said.

“Come now,” Thorvaldsen said. “There are too many examples of contradictions for us to simply dismiss them as intentional. Let’s look at it in generalities. John’s Gospel mentions much that the other three—the so-called synoptic Gospels—completely ignore. The tone in John is also different, the message more refined. John’s is like an entirely different testimony. But some of the more precise inconsistencies start with Matthew and Luke. Those are the only two that say anything of Jesus’s birth and ancestry, and even they conflict. Matthew says Jesus was an aristocrat, descended from David, in line to be king. Luke agrees with the David connection, but points to a lesser class. Mark went an entirely different direction and spawned the image of a poor carpenter.

“Jesus’s birth is likewise told from differing perspectives. Luke says shepherds visited. Matthew called them wise men. Luke said the holy family lived in Nazareth and journeyed to Bethlehem for a birth in a manger. Matthew says the family was well off and lived in Bethlehem, where Jesus was born—not in a manger, but in a house.

“But the crucifixion is where the greatest inconsistencies exist. The Gospels don’t even agree on the date. John says the day before Passover, the other three say the day after. Luke described Jesus as meek. A lamb. Matthew goes the other way—for him Jesus brings not peace, but the sword. Even the Savior’s final words varied. Matthew and Mark say it was, My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Luke says, Father, into your hands I commit my spirit. John is even simpler. It is finished.”

Thorvaldsen paused and sipped his wine.

“And the tale of the resurrection itself is completely riddled with contradictions. Each Gospel has a different version of who went to the tomb, what was found there—even the days of the week are unclear. And as to Jesus’s appearances after the resurrection—none of the accounts agree on any point. Would you not think that God would have at least been reasonably consistent with His Word?”

“Gospel variations have been the subject of thousands of books,” Malone made clear.

“True,” Thorvaldsen said. “And the inconsistencies have been there from the beginning—largely ignored in ancient times, since rarely did the four Gospels appear together. Instead, they were disseminated individually throughout Christendom—one tale working better in some places than in others. Which, in and of itself, goes a long way toward explaining the differences. Remember, the idea behind the Gospels was to demonstrate that Jesus was the Messiah predicted in the Old Testament—not to be an irrefutable biography.”

“Weren’t the Gospels just a recording of what had been passed down orally?” Stephanie asked. “Wouldn’t errors be expected?”

“No question,” Cassiopeia said. “The early Christians believed Jesus would return soon and the world would end, so they saw no need to write anything down. But after fifty years, with the Savior still not having returned, it became important to memorialize Jesus’s life. That’s when the earliest Gospel, Mark’s, was written. Matthew and Luke came next, around 80 C.E. John came much later, near the end of the first century, which is why his is so different from the other three.”

“If the Gospels were entirely consistent, wouldn’t they be even more suspect?” Malone asked.

“These books are more than simply inconsistent,” Thorvaldsen said. “They are, quite literally, four different versions of the Word.”

“It’s a matter of faith,” Stephanie repeated.

“There’s that word again,” Cassiopeia said. “Whenever a problem exists with biblical texts, the solution is easy. It’s faith. Mr. Malone, you’re a lawyer. If the testimony of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were offered in a court as proof Jesus existed, would any jury so find?”

“Sure, all of them mention Jesus.”

“Now, if that same court was required to state which one of the four books is correct, how would it rule?”

He knew the right answer. “They’re all correct.”

“So how would you resolve the differences among the testimonies?”

He didn’t answer, because he didn’t know what to say.

“Ernst Scoville did a study once,” Thorvaldsen said. “Lars told me about it. He determined that there was a ten to forty percent variation among the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke on any passage you cared to compare. Any passage. And with John, which is not one of the synoptics, the percentage was much higher. So Cassiopeia’s question is fair, Cotton. Would these four testimonies have any probative value, beyond establishing that a man named Jesus may have lived?”

He felt compelled to say, “Could all of the inconsistencies be explained by the writers simply taking liberties with an oral tradition?”

Thorvaldsen nodded. “That explanation makes sense. But what compounds its acceptance is that nasty word faith. You see, to millions, the Gospels are not the oral traditions of radical Jews establishing a new religion, trying to secure converts, recounting their tale with additions and subtractions necessary for their particular time. No. The Gospels are the Word of God, and the resurrection is its keystone. For their Lord to have sent His son to die for them, and for Him to be physically resurrected and ascend into heaven—that set them far apart from all other emerging religions.”

Malone faced Mark. “Did the Templars believe this?”

“There’s an element of Gnosticism to the Templar creed. Knowledge is passed to the brothers in stages, and only the highest in the Order know all. But no one has known that knowledge since the loss of the Great Devise during the 1307 Purge. All of the masters who came after that time were denied the Order’s archive.”

He wanted to know, “What do they think of Jesus Christ today?”

“The Templars look equally to both the Old and New Testaments. In their eyes, the Jewish prophets in the Old Testament predicted the Messiah, and the writers of the New Testament fulfilled those predictions.”

“It is like the Jews,” Thorvaldsen said, “of whom I may speak since I am one. Christians for centuries have said that Jews failed to recognize the Messiah when He came, which was why God created a new Israel in the form of the Christian Church—to take the place of the Jewish Israel.”

“His blood be upon us and upon our children,” Malone muttered, quoting what Matthew had said about the Jews’ willingness to accept that blame.

Thorvaldsen nodded. “That phrase has been used for two millennia as a reason for killing Jews. What could a people expect from God when they’d rejected His own son as their Messiah? Words that some unknown Gospel writer penned, for whatever reason, became the rally cry of murderers.”

“So what Christians finally did,” Cassiopeia said, “was separate themselves from that past. They named half the Bible the Old Testament, the other the New. One was for Jews, the other for Christians. The twelve tribes of Israel in the Old were replaced by the twelve apostles in the New. Pagan and Jewish beliefs were assimilated and modified. Jesus, through the writings of the New Testament, fulfilled the prophecies of the Old Testament, thereby proving His messianic claim. A perfectly assembled package—the right message, tailored to the right audience—all of which allowed Christianity to utterly dominate the Western world.”

Attendants appeared, and Cassiopeia signaled for them to clear away the lunch dishes. Wineglasses were refilled and coffee was passed around. As the last attendant withdrew, Malone asked Mark, “Do the Templars believe in the actual resurrection of Christ?”

“Which ones?”

A strange question. Malone shrugged.

“Those today—of course. With few exceptions, the Order follows traditional Catholic doctrine. Some adjustments are made to conform to Rule, as all monastic societies must. But in 1307? I have no idea what they believed. The Chronicles from that time are cryptic. Like I said, only the highest officers within the Order could have spoken on that subject. Most Templars were illiterate. Even Jacques de Molay could not read or write. So only a few within the Order controlled what the many thought. Of course, the Great Devise existed then, so I assume seeing was believing.”

“What is this Great Devise?”

“I wish I knew. That information has been lost. The Chronicles speak little of it. I assume it’s evidence of what the Order believed.”

“Is that why they search for it?” Stephanie asked.

“Until recently, they haven’t really searched. There’s been little information relating to its whereabouts. But the master told Geoffrey that he believed Dad was on the right track.”

“Why does de Roquefort want it so bad?” Malone asked Mark.

“Finding the Great Devise, depending on what’s there, could well fuel the reemergence of the Order onto the world scene. That knowledge could also fundamentally change Christendom. De Roquefort wants retribution for what happened to the Order. He wants the Catholic Church exposed as hypocritical, the Order’s name cleared.”

Malone was puzzled. “What do you mean?”

“One of the charges leveled against the Templars in 1307 was idol worshiping. Some sort of bearded head the Order supposedly venerated, none of which was ever proven. Yet even now Catholics pray to images routinely, the Shroud of Turin being one of those.”

Malone recalled what one of the Gospels said about Christ’s death—after they had taken him down they wrapped him in a sheet—symbolism so sacred that a later pope decreed that mass should always be said upon a linen tablecloth. The Shroud of Turin, which Mark mentioned, was a cloth of herringbone weave on which was displayed a man—six feet tall, sharp nose, shoulder-length hair parted down the center, full beard, with crucifixion wounds to his hands, feet, and scalp, and scourge marks ravaging his back.

“The image on the shroud,” Mark said, “is not of Christ. It’s Jacques de Molay. He was arrested in October 1307 and in January 1308 he was nailed to a door in the Paris Temple in a manner similar to that of Christ. They were mocking him for his lack of belief in Jesus as Savior. France’s grand inquisitor, Guíllaume Imbert, orchestrated that torture. Afterward, de Molay was wrapped in a linen shroud the Order kept in the Paris Temple for use during induction ceremonies. We now know lactic acid and blood from de Molay’s traumatized body mixed with the frankincense in the cloth and etched the image. There’s even a modern equivalent. In 1981 a cancer patient in England left a similar trace of his limbs on bedsheets.”

Malone recalled the late 1980s when the Church finally broke with tradition and allowed microscopic examination and carbon dating on the Shroud of Turin. The results indicated that there were no outlines or brushstrokes. The coloration lay upon the linen. Dating showed that the cloth came not from the first century, but from the late thirteenth to the mid-fourteenth century. But many contested those findings, saying the sample had been tainted, or was from a later repair to the original cloth.

“The image on the shroud fits de Molay physically,” Mark said. “There are descriptions of him in the Chronicles. By the time he was tortured his hair had grown long, his beard was unkempt. The cloth that wrapped de Molay’s body was removed from the Paris Temple by one of Geoffrey de Charney’s relatives. De Charney burned at the stake in 1314 with de Molay. The family kept the cloth as a relic and later noticed that an image had settled upon it. The shroud initially appeared on a religious medallion that dated to 1338 and was first displayed in 1357. When it was shown, people immediately associated the image with Christ, and the de Charney family did nothing to dissuade that belief. That went on until the late sixteenth century when the Church took possession of the shroud, declaring it acheropita—not made by human hand—deeming it a holy relic. De Roquefort wants to take the shroud back. It’s the Order’s, not the Church’s.”

Thorvaldsen shook his head. “That’s foolishness.”

“It’s how he thinks.”

Malone noticed the annoyed look on Stephanie’s face. “The Bible lesson was fascinating, Henrik. But I’m still waiting for the truth about what’s happening here.”

The Dane smiled. “You’re such a joy.”

“Chalk it up to my bubbly personality.” She displayed her phone. “Let me make myself real clear. If I don’t get some answers in the next few minutes, I’m calling Atlanta. I’ve had my fill of Raymond de Roquefort, so we’re going public with this little treasure hunt and ending this nonsense.”

MALONE WINCED AT STEPHANIE’S DECLARATION. HE’D BEEN WONDERING when her patience would run out.

“You can’t do that,” Mark said to his mother. “The last thing we need is for the government to be involved.”

“Why not?” Stephanie asked. “That abbey should be raided. Whatever they’re doing is certainly not religious.”

“On the contrary,” Geoffrey said in a tremulous voice. “Great piety exists there. The brothers are devoted to the Lord. Their lives are consumed with His worship.”

“And in between you learn about explosives, hand-to-hand combat, and how to shoot a weapon like a marksman. A bit of a contradiction, wouldn’t you say?”

“Not at all,” Thorvaldsen declared. “The original Templars were devoted to God and were a formidable fighting force.”

Stephanie was clearly not impressed. “This is not the thirteenth century. De Roquefort has both an agenda and the might to press that agenda onto others. Today we call him a terrorist.”

“You haven’t changed a bit,” Mark spat out.

“No, I haven’t. I still believe that covert organizations with money, weapons, and chips on their shoulders are problems. My job is to deal with them.”

“This doesn’t concern you.”

“Then why did your master involve me?”

Good question, Malone thought.

“You didn’t understand when Dad was alive, and you don’t now.”

“Then why don’t you clear up my confusion?”

“Mr. Malone,” Cassiopeia said in pleasant tone. “How would you like to see the castle restoration project?”

Apparently their hostess wanted to speak with him alone. Which was fine—he had some questions for her, too. “I’d love that.”

Cassiopeia pushed back her chair and stood from the table. “Then let me show you. That’ll give everyone else here time to talk—which, clearly, needs to happen. Please, make yourselves at home. Mr. Malone and I will return in a short while.”

He followed Cassiopeia outside into the bright afternoon. They strolled back down the shaded lane, toward the car park and the construction site.

“When finished,” Cassiopeia told him, “a thirteenth-century castle will stand exactly as it did seven hundred years ago.”

“Quite an endeavor.”

“I thrive on grand endeavors.”

They entered the construction site through a broad wooden gate and strolled into what appeared to be a barn with sandstone walls that housed a modern reception center. Beyond loomed the smell of dust, horses, and debris, where a hundred or so people milled about.

“The entire foundation for the perimeter has been laid and the west curtain wall is coming along,” Cassiopeia said, pointing. “We’re about to start the corner towers and central buildings. But it takes time. We have to fashion the bricks, stone, wood, and mortar precisely as was done seven hundred years ago, using the same methods and tools, even wearing the same clothes.”

“Do they eat the same food?”

She smiled. “We do make some modern accommodation.”

She led him through the construction area and up the slope of a steep hill to a modest promontory, where everything could be clearly seen.

“I come here often. One hundred and twenty men and women are employed down there full time.”

“Quite a payroll.”

“A small price to pay for history to be seen.”

“Your nickname, Ingénieur. Is that what they call you? Engineer?”

“The staff gave me that name. I’m trained in medieval building techniques. I’ve designed this entire project.”

“You know, on the one hand, you’re an arrogant bitch. On the other, you can be rather interesting.”

“I realize my comment at lunch, about what happened with Henrik’s son, was inappropriate. Why didn’t you strike back?”

“For what? You didn’t know what the hell you were talking about.”

“I’ll try not to make any more judgments.”

He chuckled. “I doubt that, and I’m not that sensitive. I long ago developed a lizard skin. You have to in order to survive in this business.”

“But you’re retired.”

“You never really quit. You just stay out of the line of fire more often than not.”

“So you’re helping Stephanie Nelle simply as a friend?”

“Shocking, isn’t it?”

“Not at all. In fact, it’s entirely consistent with your personality.”

Now he was curious. “How do you know about my personality?”

“Once Henrik asked me to be involved, I learned a great deal about you. I have friends in your former profession. They all spoke highly of you.”

“Glad to know folks remember.”

“Do you know much about me?” she asked.

“Just a thumbnail sketch.”

“I have many peculiarities.”

“Then you and Henrik should get along well.”

She smiled. “I see you know him well.”

“How long have you known him?”

“Since childhood. He knew my parents. Many years ago, he told me of Lars Nelle. What Lars was working on fascinated me. So I became Lars’s guardian angel, though he thought of me as the devil. Unfortunately, I couldn’t help him on the last day of his life.”

“Were you there?”

She shook her head. “He’d traveled south to the mountains. I was here when Henrik called and told me the body had been found.”

“Did he kill himself?”

“Lars was a sad man, that was plain. He was also frustrated. All those amateurs who’d seized on his work and twisted it beyond recognition. The puzzle he tried to solve has remained a mystery a long time. So, yes, it’s possible.”

“What were you protecting him from?”

“Many tried to encroach on his research. Most of them were ambitious treasure hunters, some opportunists, but eventually Raymond de Roquefort’s men appeared. Luckily, I was always able to conceal my presence from them.”

“De Roquefort is now master.”

She crinkled her brow. “Which explains his renewed search efforts. He now commands all the Templar resources.”

She apparently knew nothing about Mark Nelle and where he’d been living the past five years, so he told her, then said, “Mark lost to de Roquefort in the selection of a new master.”

“So this is personal between them?”

“That’s certainly part of it.” But not all, he thought, as he stared down and watched a horse-drawn cart work its way across the dry earth toward one of the partial walls.

“The work being done today is for the tourists,” she said, noticing his interest. “Part of the show. We’ll return to serious building tomorrow.”

“The sign out front said it’ll take thirty years to finish.”

“Easily.”

She was right. She did possess many peculiarities.

“I intentionally left Lars’s notebook for de Roquefort to find in Avignon.”

That revelation shocked him. “Why?”

“Henrik wanted to talk to the Nelles privately. It’s why we’re here. He also said that you’re a man of honor. I trust precious few people in this world, but Henrik is one I do. So I’m going to take him at his word and tell you some things no one else knows.”

MARK LISTENED AS HENRIK THORVALDSEN EXPLAINED. HIS mother appeared interested, too, but Geoffrey simply stared at the table, hardly blinking, seemingly in a trance.

“It’s time you fully understand what Lars believed,” Henrik said to Stephanie. “Contrary to what you may have thought, he was not some crackpot chasing after treasure. A serious purpose lay behind his inquiries.”

“I’ll ignore your insult, since I want to hear what you have to say.”

A look of irritation crept into Thorvaldsen’s eyes. “Lars’s theory was simple, though it really was not his. Ernst Scoville formulated most of it, which involved a novel look at the Gospels of the New Testament, especially with how they dealt with the resurrection. Cassiopeia hinted at some of this earlier.

“Let’s start with Mark’s. His was the first Gospel, written around AD 70, perhaps the only Gospel the early Christians possessed after Christ died. It contains six hundred sixty-five verses, yet only eight are devoted to the resurrection. This most remarkable of events only rated a brief mention. Why? The answer is simple. When Mark’s Gospel was written, the story of the resurrection had yet to develop, and the Gospel ends without mention of the fact that the disciples believed Jesus had been raised from the dead. Instead, it tells us that the disciples fled. Only women appear in Mark’s version of what happened, and they ignore a command to tell the disciples to go to Galilee so the risen Christ could meet them there. Rather, the women, too, are confused and flee, telling no one what they saw. There are no angels, only a young man dressed in white who calmly announces that He has risen. No guards, no burial clothes, and no risen Lord.”

Mark knew everything Thorvaldsen had just said was true. He’d studied that Gospel in great detail.

“Matthew’s testimony came a decade later. The Romans had by then sacked Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple. Many Jews had fled into the Greek-speaking world. The Orthodox Jews who stayed in the Holy Land viewed the new Jewish Christians as a problem—as much of one as the Romans were. Hostility existed between the Orthodox Jews and the emerging Jewish Christians. Matthew’s Gospel was probably written by one of those unknown Jewish Christian scribes. Mark’s Gospel had left many unanswered questions, so Matthew changed the story to suit his troubled time.

“Now the messenger who announces the resurrection becomes an angel. He descends in an earthquake, with a face like lightning. Guards are struck down. The stone has been removed from the tomb, and an angel perches upon it. The women are still gripped with fear, but it is rapidly replaced with joy. Contrary to the women in Mark’s account, the women here rush out to tell the disciples what’s happened and actually confront the risen Christ. Here, for the first time, the risen Lord is actually described. And what did the women do?”

“They took hold of His feet and worshiped Him,” Mark softly said. “Later, Jesus appeared to His disciples and proclaimed that ‘all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me.’ He tells them he’ll always be with them.”

“What a change,” Thorvaldsen said. “The Jewish Messiah named Jesus has now become Christ to the world. In Matthew, everything is more vivid. Miraculous, too. Then comes Luke, sometime around AD 90. By then the Jewish Christians had moved further away from Judaism, so Luke radically modified the resurrection story to accommodate this change. The women are at the tomb again, but this time they find it empty and go tell the disciples. Peter returns and sees only the discarded burial clothes. Then Luke tells a story that appears nowhere else in the Bible. It involves Jesus traveling in disguise, encountering certain disciples, sharing a meal, then, when recognized, vanishing. There is also a later encounter with all of the disciples where they doubt His flesh, so He eats with them, then vanishes. And only in Luke do we find the story of Jesus’s ascension into heaven. What’s happened? A sense of rapture has now been grafted onto the risen Christ.”

Mark had read similar Scripture analyses in the Templar archives. Learned brothers had for centuries studied the Word, noting errors, evaluating contradictions, and hypothesizing on the many conflicts in names, dates, places, and events.

“Then there’s John,” Thorvaldsen said. “The Gospel written the furthest away from Jesus’s life, around AD 100. There are so many changes in this Gospel, it’s almost as if John talks of a totally different Christ. No Bethlehem birth—Nazareth is Jesus’s birthplace here. The other three talk of a three-year ministry. John says only one. The Last Supper in John occurred on the day before the Passover—the crucifixion on the day the Passover lamb was slaughtered. This is different from the other Gospels. John also moved the cleansing of the Temple from the day after Palm Sunday to a time early in Christ’s ministry.

“In John, Mary Magdalene alone goes to the tomb and finds it empty. She never even considers a resurrection, but instead thinks the body has been stolen. Only when she returns with Peter and the other disciple does she see two angels. Then the angels are transformed into Jesus Himself.

“Look how this one detail, about who was in the tomb, changed. Mark’s young man dressed in white became Matthew’s dazzling angel, which Luke expanded to two angels, which John modified to two angels who become Christ. And was the risen Lord seen in the garden on the first day of the week, as Christians are always told? Mark and Luke said no. Matthew, yes. John said not at first, but Mary Magdalene did see Him later. What happened is clear. Over time, the resurrection was made more and more miraculous to accommodate a changing world.”

“I assume,” Stephanie said, “you don’t adhere to the principle of biblical inerrancy?”

“There’s nothing whatsoever literal within the Bible. It’s a tale riddled with inconsistencies, and the only way they can be explained is through the use of faith. That may have worked a thousand years ago, or even five hundred years ago, but that explanation is no longer acceptable. The human mind today questions. Your husband questioned.”

“So what was it Lars meant to do?”

“The impossible,” Mark muttered.

His mother looked at him with strangely understanding eyes. “But that never stopped him.” The voice was low and melodious, as if she’d just realized a truth that had long lain hidden. “If nothing else, he was a wonderful dreamer.”

“But his dreams had a basis,” Mark said. “The Templars once knew what Dad wanted to know. Even today, they read and study Scripture that’s not a part of the New Testament. The Gospel of Philip, the Letter of Barnabas, the Acts of Peter, the Epistle of the Apostles, the Secret Book of John, the Gospel of Mary, the Didache. And the Gospel of Thomas, which is to them perhaps the closest we have to what Jesus may have actually said, since it has not been subjected to countless translations. Many of these so-called heretical texts are eye opening. And that was what made the Templars special. The true source of their power. Not wealth or might, but knowledge.”

MALONE STOOD UNDER THE SHADE OF TALL POPLARS THAT DOTTED the promontory. A cool breeze eased past and dulled the sun’s rays, reminding him of a fall afternoon at the beach. He was waiting for Cassiopeia to tell him what nobody else knew. “Why did you allow de Roquefort to have Lars Nelle’s notebook?”

“Because it’s useless.” A crinkle of amusement slipped into her dark eyes.

“I thought it contained Lars’s private thoughts. Information he never published. The key to everything.”

“Some of that is true, but it’s not the key to anything. Lars created it just for the Templars.”

“Would Claridon have known that?”

“Probably not. Lars was a secretive man. He told no one everything. He said once that only the paranoid survived in his line of work.”

“How do you know this?”

“Henrik was aware. Lars never spoke of the details, but he told Henrik of his encounters with the Templars. On occasion, he actually believed he was speaking to the Order’s master. They talked several times, but eventually de Roquefort entered the picture. And he was altogether different. More aggressive, less tolerant. So Lars created the notebook for de Roquefort to focus on—not unlike the misdirection Saunière himself used.”

“Would the Templar master have known this? When Mark was taken to the abbey, he had the notebook with him. The master kept it hidden until a month ago, when he sent it to Stephanie.”

“Hard to say. But if he sent the notebook to Stephanie, it’s possible the master calculated that de Roquefort would again chase after it. He apparently wanted Stephanie involved, so what better way than to bait her with something irresistible?”

Smart, he had to admit. And it worked.

“The master surely felt Stephanie would use the considerable resources at her disposal to aid the quest,” she said.

“He didn’t know Stephanie. Too stubborn. She’d try it on her own first.”

“But you were there to help.”

“Lucky me.”

“Oh, it’s not that bad. We never would have met otherwise.”

“Like I said, lucky me.”

“I’ll take that as a compliment. Otherwise my feelings might be hurt.”

“I doubt you bruise so easily.”

“You handled yourself well in Copenhagen,” she said. “Then again in Roskilde.”

“You were in the cathedral?”

“For a while, but I left when the shooting started. It would have been impossible for me to help without revealing my presence, and Henrik wanted that kept secret.”

“And what if I had been unable to stop those men inside?”

“Oh, come now. You?” She threw him a smile. “Tell me something. How shocked were you when the brother leaped from the Round Tower?”

“Not something you see every day.”

“He fulfilled his oath. Trapped, he chose death rather than risk the Order’s exposure.”

“I assume you were there because of my mention to Henrik that Stephanie was coming for a visit.”

“Partly. When I heard of Ernst Scoville’s sudden demise, I learned from some of the older men in Rennes that he’d spoken with Stephanie and that she was coming to France. They’re all Rennes enthusiasts, spending their days playing chess and fantasizing about Saunière. Each one of them lives in a conspiratorialist dream. Scoville bragged that he meant to get Lars’s notebook. He didn’t care for Stephanie, though he’d led her to believe otherwise. Obviously he, too, was unaware that the journal was by and large meaningless. His death aroused my suspicions, so I contacted Henrik and learned of Stephanie’s impending Danish visit. We decided that I should go to Denmark.”

“And Avignon?”

“I had a source at the asylum. No one believed Claridon was crazy. Deceitful, untrustworthy, an opportunist—certainly. But not insane. So I watched until you returned to claim Claridon. Henrik and I knew there was something in the palace archives, just not what. As Henrik said at lunch, Mark never met Henrik. Mark was much tougher to deal with than his father. He only occasionally searched. Something, perhaps, to keep his father’s memory alive. Whatever he may have found, he kept totally to himself. He and Claridon connected for a while, but it was a loose association. Then, when Mark disappeared in the avalanche and Claridon retreated to the asylum, Henrik and I gave up.”

“Until now.”

“The quest is back on, and this time there may well be somewhere to go.”

He waited for her to explain.

“We have the book with the gravestone and we also have Reading the Rules of the Caridad. Together, we might actually be able to determine what Saunière found, since we’re the first to have so many pieces of the puzzle.”

“And what do we do if we find anything?”

“As a Muslim? I’d like to tell the world. As a realist? I don’t know. The historical arrogance of Christianity is nauseating. To it, every other religion is an imitation. Amazing, really. All of Western history is shaped by its narrow precepts. Art, architecture, music, writing—even society itself became Christianity’s servants. That simple movement ultimately formed the mold from which Western civilization was crafted, and it could all be predicated on a lie. Wouldn’t you like to know?”

“I’m not a religious person.”

Her thin lips creased into another smile. “But you’re a curious man. Henrik speaks of your courage and intellect in reverent terms. A bibliophile, with an eidetic memory. Quite a combination.”

“And I can cook, too.”

She chuckled. “You don’t fool me. Finding the Great Devise would mean something to you.”

“Let’s just say that it would be a most unusual find.”

“Fair enough. We’ll leave it at that. But if we’re successful, I look forward to seeing your reaction.”

“You’re that confident there’s something to find?”

She swept her arms toward the distant outline of the Pyrénées. “It’s out there, no question. Saunière found it. We can, too.”

STEPHANIE AGAIN CONSIDERED WHAT THORVALDSEN HAD SAID about the New Testament, and made clear, “The Bible is not a literal document.”

Thorvaldsen shook his head. “A great many Christian faiths would take issue with that statement. For them, the Bible is the Word of God.”

She looked at Mark. “Did your father believe the Bible was not the Word of God?”

“We debated the point many times. I was, at first, a believer, and I’d argue with him. But I came to think like he did. It’s a book of stories. Glorious stories, designed to point people toward a good life. There’s even greatness in those stories—if one practices their moral. I don’t think it’s necessary that it’s the Word of God. It’s enough that the words are a timeless truth.”

“Elevating Christ to deity status was simply a way of elevating the importance of the message,” Thorvaldsen said. “After organized religion took over in the third and fourth centuries, so much was added to the tale that it’s impossible any longer to know its core. Lars wanted to change all that. He wanted to find what the Templars once possessed. When he first learned of Rennes-le-Château years ago, he immediately believed the Templar’s Great Devise was what Saunière had located. So he devoted his life to solving the Rennes puzzle.”

Stephanie was still not convinced. “What makes you think the Templars secreted anything away? Weren’t they arrested quickly? How was there time to hide anything?”

“They were prepared,” Mark said. “The Chronicles make that clear. What Philip IV did wasn’t without precedent. A hundred years earlier there was an incident with Frederick II, the king of Germany and Sicily. In 1228 he arrived in the Holy Land as an excommunicate, which meant he could not command a crusade. The Templars and Hospitallers stayed loyal to the pope and refused to follow him. Only his German Teutonic knights stood by his side. Ultimately, he negotiated a peace treaty with the Saracens that created a divided Jerusalem. The Temple Mount, which was where the Templars were headquartered, was given by that treaty to the Muslims. So you can imagine what the Templars thought of him. He was as amoral as Nero and universally hated. He even tried to kidnap the Order’s master. Finally he left the Holy Land in 1229, and as he made his way to the port at Acre, the locals threw excrement on him. He hated the Templars for their disloyalty, and when he returned to Sicily, he seized Templar property and made arrests. All of which was recorded in the Chronicles.”

“So the Order was ready?” Thorvaldsen asked.

“The Order had already seen, firsthand, what a hostile ruler could do to it. Philip IV was similar. As a young man he’d applied for Templar membership and had been refused, so he harbored a lifelong resentment toward the brotherhood. Early in his reign, the Templars actually saved Philip when he tried to devalue the French currency and the people revolted. He fled to the Paris Temple for refuge. Afterward, he felt beholden to the Templars. And monarchs never want to owe anyone. So, yes, by October 1307 the Order was ready. Unfortunately, nothing is recorded that tells us the details of what was done.” Mark’s gaze bored into Stephanie. “Dad gave his life to try to solve that mystery.”

“He did love looking, didn’t he?” Thorvaldsen said.

Though answering the Dane, Mark continued to face her. “It was one of the few things that actually brought him joy. He wanted to please his wife and himself and, unfortunately, he could do neither. So he opted out. Decided to leave us all.”

“I never wanted to believe he killed himself,” she said to her son.

“But we’ll never know, will we?”

“Perhaps you may,” Geoffrey said. And for the first time the young man lifted his gaze from the table. “The master said you might learn the truth of his death.”

“What do you know?” she asked.

“I know only what the master told me.”

“What did he tell you about my father?” Anger gripped Mark’s face. Stephanie could never recall seeing him vent that emotion on anyone but her.

“That will have to be learned, by you. I don’t know.” The voice was strange, hollow, and conciliatory. “The master told me to be tolerant of your emotion. He made clear you’re my senior, and I should offer you nothing but respect.”

“But you seem to be the only one with answers,” Stephanie said.

“No, madame. I know but markers. The answers, the master said, must come from all of you.”

MALONE FOLLOWED CASSIOPEIA INTO A LOFTY CHAMBER WITH A raftered ceiling and paneled walls hung with tapestries that depicted cuirasses, swords, lances, casques, and shields. A black marble fireplace dominated the long room, which was lit by a glittering chandelier. The others joined them from the dining room and he noticed serious expressions on all of their faces. A mahogany table sat beneath a set of mullioned windows, across which were spread books, papers, and photographs.

“Time we see if there are any conclusions we can reach,” Cassiopeia said. “On the table is everything I have on this subject.”

Malone told the others about Lars’s notebook and how some of the information contained within it was false.

“Does that include what he said about himself?” Stephanie asked. “This young man here—” She pointed at Geoffrey. “—sent me pages from the journal—pages his master cut out. They talked about me.”

“Only you know if what he said was true or more misdirection,” Cassiopeia said.

“She’s right,” Thorvaldsen said. “The notebook is, by and large, not genuine. Lars created it as Templar bait.”

“Another point you conveniently failed to mention back in Copenhagen.” Stephanie’s tone signaled she was once again annoyed.

Thorvaldsen was undaunted. “The important thing was that de Roquefort thought the journal genuine.”

Stephanie’s back straightened. “You son of a bitch, we could have been killed trying to get it back.”

“But you weren’t. Cassiopeia kept an eye on you both.”

“And that makes what you did right?”

“Stephanie, you’ve never withheld information from one of your agents?” Thorvaldsen asked.

She held her tongue.

“He’s right,” Malone said.

She whirled and faced him.

“How many times did you tell me only part of the story?” “And how many times did I complain later that it could have gotten me killed? And what did you say? Get used to it. Same here, Stephanie. I don’t like it any better than you do, but I got used to it.”

“Why don’t we stop arguing and see if we can come to some consensus as to what Saunière may have found,” Cassiopeia said.

“And where would you suggest we start?” Mark asked.

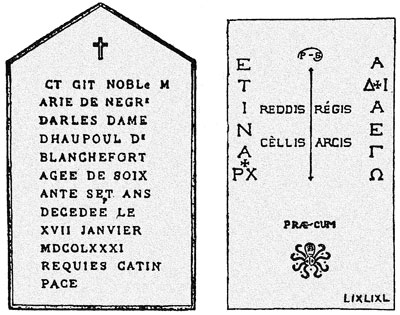

“I’d say Marie d’Hautpoul de Blanchefort’s gravestone would be an excellent spot, since we have Stüblein’s book that Henrik purchased at the auction.” She motioned to the table. “Opened to the drawing.”

They all stepped close and gazed at the sketch.

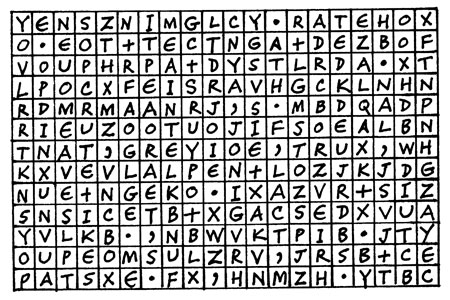

“Claridon explained about this in Avignon,” Malone said, and he told them about the wrong date of death—1681 as opposed to 1781—the Roman numerals—MDCOLXXXI—containing a zero, and the remaining set of Roman numerals—LIXLIXL—etched into the lower right corner.

Mark grabbed a pencil off the table and wrote 1681 and 59, 59, 50 on a pad. “That’s the conversion of those numbers. I’m ignoring the zero in the 1681. Claridon’s right, no zero in Roman numerals.”

Malone pointed at the Greek letters on the left stone. “Claridon said they were Latin words written in the Greek alphabet. He converted the lettering and came up with Et in arcadia ego. And in Arcadia I. He thought it might be an anagram, since the phrase makes little sense.”

Mark studied the words with intensity, then asked Geoffrey for the rucksack, from which he removed a tightly folded towel. He gently unwrapped the bundle and revealed a small codex. Its leafs were folded, then sewn together and bound—vellum, if Malone wasn’t mistaken. He’d never seen one he could actually touch.

“This came from the Templar archives. I found it a few years ago, right after I became seneschal. It was written in 1542 by one of the abbey’s scribes. It’s an excellent reproduction of a fourteenth-century manuscript and recounts how the Templars re-formed after the Purge. It also deals with the time from December 1306 until May 1307, when Jacques de Molay was in France and little is known of his whereabouts.”

Mark gently opened the ancient volume and carefully paged through until he found what he was looking for. Malone saw the Latin script was a series of loops and fioriture, the letters joined together from the pen not being lifted from the page.

“Listen to this.”

Our master, the most reverend and devoted Jacques de Molay, received the pope’s envoy on 6 June 1306 with the pomp and courtesy reserved for those of high rank. The message stated that His Holiness Pope Clement V hath summoned Master de Molay to France. Our master intended to comply with that order, making all preparations, but prior to leaving the island of Cyprus, where the Order hath established its headquarters, our master learned that the leader of the Hospitallers had also been summoned, but hath refused the command, citing the need to remain with his Order in time of conflict. This aroused great suspicion in our master and he consulted with his officers. His Holiness had likewise instructed our master to travel unrecognized and with a small retinue. This raised more questions since why would His Holiness care how our master moved through the lands. Then a curious document was brought to our master titled De Recuperatione Terrae Sanctae. Concerning the Recovery of the Holy Land. The manuscript was written by one of Philip IV’s lawyers and it outlined a grand new crusade to be headed by a Warrior King designed to retake the Holy Land from the infidels. This proposal was a direct affront to the plans of our Order and caused our master to question his summons to the King’s court. Our master made it known that he greatly distrusted the French monarch, though it would be both foolish and inappropriate for him to voice that mistrust beyond the walls of our Temple. In a mood of caution, being not a careless man and remembering the treachery from long ago of Frederick II, our master laid plans that our wealth and knowledge must be safeguarded. He prayed that he might be in error but saw no reason to be unprepared. Brother Gilbert de Blanchefort was summoned and ordered to take away the treasure of the Temple in advance. Our master then told de Blanchefort, “We of the Order’s leadership could be at risk. So none of us are to know what you know and you must assure that what you know is passed to others in an appropriate manner.” Brother de Blanchefort, being a learned man, set about to accomplish his mission and quietly secreted all that the Order had acquired. Four brothers were his allies and they used four words, one for each of them, as their signal.ET IN ARCADIA EGO. But the letters are but a jumble for the true message. A rearrangement tells precisely what their task entailed.I TEGO ARCANA DEI.

“I conceal the secrets of God,” Mark said, translating the last line. “Anagrams were common in the fourteenth century, too.”

“So de Molay was ready?” Malone asked.

Mark nodded. “He came to France with sixty knights, a hundred fifty thousand gold florins, and twelve pack horses hauling unminted silver. He knew there was going to be trouble. That money was to be used to buy his way out. But there’s something contained within this treatise that is little known. The commander of the Templar contingent in the Languedoc was Seigneur de Goth. Pope Clement V, the man who summoned de Molay, was named Bertrand de Goth. The pope’s mother was Ida de Blanchefort, who was related to Gilbert de Blanchefort. So de Molay possessed good inside information.”

“Always helps,” Malone said.

“De Molay also knew something on Clement V. Prior to his election as pope, Clement met with Philip IV. The king had the power to deliver the papacy to whomever he wanted. Before he gave it to Clement, he imposed six conditions. Most had to do with Philip getting to do whatever he wanted, but the sixth concerned the Templars. Philip wanted the Order dissolved, and Clement agreed.”

“Interesting stuff,” Stephanie said, “but what seems more important at the moment is what the abbé Bigou knew. He’s the man who actually commissioned Marie’s gravestone. Would he have known of a connection between the de Blanchefort family secret and the Templars?”

“Without a doubt,” Thorvaldsen said. “Bigou was told the family secret by Marie d’Hautpoul de Blanchefort herself. Her husband was a direct descendant of Gilbert de Blanchefort. Once the Order was suppressed, and Templars started burning at the stake, Gilbert de Blanchefort would have told no one the location of the Great Devise. So that family secret has to be Templar-related. What else could it be?”

Mark nodded. “The Chronicles speak of carts topped with hay moving through the French countryside, each headed south toward the Pyrénées, escorted by armed men disguised as peasants. All but three made the journey safely. Unfortunately, there’s no mention of their final destination. Only one clue in all the Chronicles. Where is it best to hide a pebble?”

“In the middle of a rock pile,” Malone said.

“That’s what the master said, too,” Mark said. “To the fourteenth-century mind, the most obvious location would be the safest.”

Malone gazed again at the gravestone drawing. “So Bigou had this gravestone carved that, in code, says that he conceals the secrets of God, and he went to the trouble of publicly placing it. What was the point? What are we missing?”

Mark reached into the rucksack and extracted another volume. “This is a report by the Order’s marshal written in 1897. The man was investigating Saunière and came across another priest, the abbé Gélis, in a nearby village, who found a cryptogram in his church.”

“As Saunière did,” Stephanie said.

“That’s right. Gélis deciphered the cryptogram and wanted the bishop to know what he learned. The marshal posed as the bishop’s representative and copied the puzzle, but he kept the solution to himself.”

Mark showed them the cryptogram and Malone studied the lines of letters and symbols. “Some sort of numeric key unscrambles it?”

Mark nodded. “It’s impossible to break without the key. There are billions of possible combinations.”

“There was one of these in your father’s journal, too,” he said.

“I know. Dad found it in Noël Corbu’s unpublished manuscript.”

“Claridon told us about that.”

“Which means de Roquefort has it,” Stephanie said. “But is it part of the fiction of Lars’s journal?”

“Anything Corbu touched has to be suspect,” Thorvaldsen made clear. “He embellished Saunière’s story to promote his damn hotel.”

“But the manuscript he wrote,” Mark said. “Dad always believed it contained truth. Corbu was close with Saunière’s mistress up until she died in 1953. Many believed she told him things. That’s why Corbu never published the manuscript. It contradicted his fictionalized version of the story.”

“But surely the cryptogram in the journal is false?” Thorvaldsen said. “That would have been the very thing de Roquefort would have wanted from the journal.”

“We can only hope,” Malone said, as he noticed an image of Reading the Rules of the Caridad on the table. He lifted the letter-sized reproduction and studied the writing beneath the little man, in a monk’s robe, perched on a stool with a finger to his lips, signaling quiet.

ACABOCE Aº

DE 1681

Something was wrong, and he instantly compared the image with the lithograph.

The dates were different.

“I spent this morning learning about that painting,” Cassiopeia said. “I found that image on the Internet. The painting was destroyed by fire in the late 1950s, but prior to that the canvas had been cleaned and readied for display. During the restoration process it was discovered that 1687 was actually 1681. But of course, the lithograph was drawn at a time when the date was obscured.”

Stephanie shook her head. “This is a puzzle with no answer. Everything changes by the minute.”

“You’re doing precisely what the master wanted,” Geoffrey said.

They all looked at him.

“He said that once you combined, all would be revealed.”

Malone was confused. “But your master specifically warned us to Beware the engineer.”

Geoffrey motioned to Cassiopeia. “Perhaps you should beware of her.”

“What does that mean?” Thorvaldsen asked.

“Her race fought the Templars for two centuries.”

“Actually, the Muslims trounced the brothers and sent them packing from the Holy Land,” Cassiopeia declared. “And Spanish Muslims kept the Order in check here in the Languedoc when the Templars tried to expand their sphere south, beyond the Pyrénées. So your master was right. Beware the engineer.”

“What would you do if you found the Great Devise?” Geoffrey asked her.

“Depends on what there is to find.”

“Why does that matter? The Devise is not yours, regardless.”

“You’re quite forward for a mere brother of the Order.”

“Much is at stake here, the least of which is your ambition to prove Christianity a lie.”

“I don’t recall saying that was my ambition.”

“The master knew.”

Cassiopeia’s face screwed tight—the first time Malone had seen agitation in her expression. “Your master knew nothing of my motives.”

“And by keeping them hidden,” Geoffrey said, “you do nothing but confirm his suspicion.”

Cassiopeia faced Henrik. “This young man could be a problem.”

“He was sent by the master,” Thorvaldsen said. “We shouldn’t question.”

“He’s trouble,” Cassiopeia declared.

“Maybe so,” Mark said. “But he’s part of this, so get used to him.”

She stayed calm and unruffled. “Do you trust him?”

“Doesn’t matter,” Mark said. “Henrik’s right. The master trusted him and that’s what matters. Even if the good brother can be irritating.”

Cassiopeia did not push the point, but on her brow was written the shadow of mutiny. And Malone did not necessarily disagree with her impulse.

He turned his attention back to the table and stared at the color images taken at the Church of Mary Magdalene. He noticed the garden with the statue of the Virgin and the words MISSION 1891 and PENITENCE, PENITENCE carved into the face of the upside-down Visigoth pillar. He shuffled through close-up shots of the stations of the cross, pausing for a moment on station 10, where a Roman soldier was gambling for Christ’s cloak, the numbers three, four, and five visible on the dice faces. Then he paused on station 14, which showed Christ’s body being carried under cover of darkness by two men.

He remembered what Mark had said in the church, and he couldn’t help wondering. Was their route into the tomb or out?

He shook his head.

What in the world was happening?

5:30 PM

DE ROQUEFORT FOUND THE GIVORS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE, WHICH was clearly denoted on the Michelin map, and approached with a measure of caution. He did not want to announce his presence. Even if Malone and company were not there, Cassiopeia Vitt knew him. So on arriving, he ordered the driver to slowly cruise through a grassy meadow that served as a car park until he found the Peugeot matching the make and color he remembered, with a rental sticker on the windshield.

“They’re here,” he said. “Park.”

The driver did as instructed.

“I’ll explore,” he told the other two brothers and Claridon. “Wait here, and remain out of sight.”

He climbed out into the late afternoon, a blood ball of summer sun already fading over the surrounding walls of limestone. He sucked in a deep breath and savored cool, thin air that reminded him of the abbey. They’d clearly risen in altitude.

A quick visual survey and he spotted a tree-shaded lane cast in long shadows and decided that direction seemed best, but he stayed off the defined path, making his way through the tall trees, a tapestry of flowers and heather carpeting the violet ground. The surrounding land had all once been a Templar domain. One of the largest commanderies in the Pyrénées had crowned a nearby promontory. It had been a factory, one of several locations where brothers labored night and day crafting the Order’s weapons. He knew that great skill had gone into compacting wood, leather, and metal into shields that could not be easily split. But the sword had been the brother knight’s true friend. Barons often loved their swords more than their wives, and tried to retain the same one all of their lives. Brothers cradled a similar passion, which Rule encouraged. If a man was expected to lay down his life, the least that could be done was allow him the weapon of his choice. Templar swords, however, were not like those of barons. No hilts adorned with gilt or set with pearls. No end knobs capped in crystal containing relics. Brother knights required no such talismans, as their strength came from a devotion to God and obedience to Rule. Their companion had been their horse, always one with quickness and intelligence. Each knight was allocated three animals, which were fed, combed, and tricked out each day. Horses were one of the means whereby the Order flourished, and the coursers, the palfreys, and especially the destriers responded to the brother knights’ affection with an unmatched loyalty. He’d read of one brother who returned home from the Crusades and was not embraced by his father, but was instantly recognized by his faithful stallion.

And they were always stallions.

To ride a mare was unthinkable. What had one knight said? The woman to the woman.

He kept walking. The musty scent of twigs and boughs stirred his imagination, and he could almost hear the heavy hooves that had once crushed the tender mosses and flowers. He tried to listen for some sound, but the clicking of grasshoppers interfered. He was mindful of electronic surveillance but had, so far, sensed none. He continued to thread a path through the tall pines, moving farther away from the lane, deeper into the woods. His skin heated, and sweat beaded on his brow. High above him, rock crannies groaned from a wind.

Warrior monks, that’s what the brothers became.

He liked that term.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux himself justified the Templars’ entire existence by glorifying the killing of non-Christians. Neither dealing out death nor dying, when for Christ’s sake, contains anything criminal but rather merits glorious reward. The soldier of Christ kills safely and dies the more safely. Not without cause does he bear the sword. He is the instrument of God for the punishment of evildoers and for the defense of the just. When he kills evildoers it is not homicide, but malicide, and he is considered Christ’s legal executioner.

He knew those words well. They were taught to every inductee. He’d repeated them in his mind as he’d watched Lars Nelle, Ernst Scoville, and Peter Hansen die. All were heretics. Men who’d stood in the Order’s way. Malice doers. Now there were a few more names to be added to that list. Those of the men and women who occupied the château that was coming into view, beyond the trees, in a sheltered hollow among a succession of rock ridges.

He’d learned something of the château from the background information he’d ordered earlier, before leaving the abbey. Once a sixteenth-century royal residence, one of Catherine de Médicis’ many homes, it had been spared destruction in the Revolution due to its isolation. So it remained a monument to the Renaissance—a picturesque mass of turrets, spires, and perpendicular roofs. Cassiopeia Vitt was clearly a woman of means. Houses such as this required great sums of money to buy and maintain, and he doubted she conducted tours as a way to supplement the income. No, this was the private residence of an aloof soul, one that had three times interfered in his business. One that must be tended to.

But he also needed the two books Mark Nelle possessed.

So rash acts were out of the question.

The day was fast falling, deep shadows already starting to engulf the château. His mind whirled with possibilities.

He had to be sure they were all inside. His current vantage point was too close. But he spied a thick stand of beech trees two hundred meters away that would provide an unobstructed view of the front entrance.

He had to assume that they expected him to come. After what happened in Lars Nelle’s house, they surely realized Claridon was working for him. But they might not expect him here this soon. Which was fine. He needed to return to the abbey. His officers were awaiting him. A council had been called that demanded his presence.

He decided to leave the two brothers in the car here to watch. That would be enough for now.

But he’d be back.

8:00 PM

STEPHANIE COULD NOT RECALL THE LAST TIME SHE AND MARK had sat and talked. Perhaps not since he was a teenager. That was how deep the chasm between them ran.

Now they had retreated to a room atop one of the château’s towers. Before sitting, Mark had swung open four oriel windows, allowing the keen evening air to wash over them.

“You may or may not believe this, but I think about you and your father every day. I loved your father. But once he came across the Rennes story, he changed his focus. That whole thing took him over. And at the time, I resented that.”

“Which I can understand. Really, I can. What I don’t understand is why you made him choose between you and what he thought was important.”

His sharp tone bristled through her, and she forced herself to remain calm. “The day we buried him, I knew how wrong I’d been. But I couldn’t bring him back.”

“I hated you that day.”

“I know.”

“Yet you just flew home and left me in France.”

“I thought that was what you wanted.”

“It was. But for the past five years I’ve had a lot of time to reflect. The master championed you, though I’m only now realizing what he meant by a lot of his comments. In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus says, Whoever does not hate their father and mother as I do cannot be my disciple. Then He says, Whoever does not love their father and mother as I do cannot be my disciple. I’m beginning to understand those contradictory statements. I hated you, Mother.”

“But do you love me, too?”

Silence loomed between them, and it tore at her heart.

Finally, he said, “You’re my mother.”

“That’s not an answer.”

“It’s all you’re going to get.”

His face, so much like Lars’s, was a study in conflicting emotions. She didn’t press. Her chance to demand anything had long passed.

“Are you still head of the Magellan Billet?” he asked.

She appreciated the change in subject. “As far as I know, but I’ve probably pushed my luck the past few days. Cotton and I haven’t been inconspicuous.”

“He seems like a good man.”

“The best. I didn’t want to involve him, but he insisted. He worked for me a long time.”

“It’s good to have friends like that.”

“You have one, too.”

“Geoffrey? He’s more my oracle than a friend. The master swore him to me. Why? I don’t know.”

“He would defend you with his life. That much is clear.”

“I’m not accustomed to people laying down their lives for me.”