By The River

Seregil leaned over the riverbank and examined the welt swelling across his left cheekbone. Angry eyes glared back up at him through the red and yellow leaves drifting past on the current: You’ve failed again. Failed at court. Failed at wizardry. Failed at the assassin’s craft, failed in your own birthright...Blood on your hands, but you can’t even make a dishonest living.

He dipped his left hand in the water, blotting out that accusing stare, and held it to his sore cheek. The old saying was right: hunger was a harsh master and a poor guide. It had been stupid, trying to pick the purse of a merchant in a rat hole river town full of thieves, worse even than trying to cheat those sailors at Isil two days earlier. They’d proven a good deal more clever than they’d looked, and taken everything he had—horse, sword, money, cloak, boots—before beating him senseless and dumping him on a garbage heap outside the town walls.

The merchant in Straightford had been clever, too. He must have paid some wandering drysian to charm his purse; the strings had tightened around Seregil’s wrist the minute he touched silver. The man had friends on the street, too, who’d been quick to come to his aid. Seregil had barely avoided another beating, and escaped by throwing himself off a bridge into the raging river that swept through the center of the town.

He looked down at the tattered remains of the purse still clinging around his right wrist. The silken bag had torn as he fought his way to shore, and what coins it had held were lost. The charmed purse strings still bit into his flesh, too tight to pull off, and he had no knife to cut them. If he hadn’t failed at all Nysander’s lessons, he reflected sourly, he might have had the wit to break the charm.

Then again, if I’d had any knack for magic, I wouldn’t be here, alone, barefoot and starving, in the woods at ass end of nowhere among stupid, ugly, flint-hearted Tírfaie, would I?

He sat back on his heels and gazed around, hating this foreign landscape almost more than he hated himself at the moment. The river, the road, the thick forest on every side, it wasn’t so different from the lands of his father’s fai’thast, yet it was.

He could go back to Rhíminee, of course; never mind all his tearful parting vows. Nysander had wept, too, when he’d left that last time, and begged him to stay, but Seregil had earned no place among wizards, only derision for his bungling.

He probably could have a place at court again, if he was willing to humble himself; he was still Queen’s kin, despite the disgrace that dogged him. They’d find him some new menial office to fill. The debacles of his failed scribeship and Orëska apprenticeship would fade in time, and rumors about him and the prince. People wouldn’t always laugh behind their hands when he passed.

Yes, they will.

The autumn sun was sinking fast now and he was too exhausted to go any further. And why bother? He’d been running away for months now, not going toward anything. He couldn’t recall the last time he’d actually had a destination.

“Piss on that!” he growled aloud. He drank some water to calm his empty belly, then looked around for shelter. Nothing in particular presented itself, so he hobbled up the hillside to a copse and hunkered down against the sunny side of a fir tree, trying to find a comfortable angle between the roots. The sun was almost touching the distant mountain tops. The gentle breeze was going cold and finding the rents in his ragged coat and breeches. Shivering, he pulled a foot up on his thigh and gingerly picked at a sharp stone lodged in his heel. The bottoms of his feet were filthy and covered in small scratches and cuts. As a child he wandered the forests of Bôkthersa on bare feet well callused and tough, but those days were long gone.

Better for you to have taken that boatman’s offer in Isil, the mocking voice in his head went on. At least you’d be under a roof. He’d probably even have stood you a tavern meal after, if you’d played him right ...

A wave of despair washed over him. Not for the first time, he wondered why he hadn’t done as the others had years ago: filled his pockets with ballast stones and thrown himself overboard that first day of exile, when his homeland slipped away under the horizon behind the ship.

The glint of sun on water winked at him through the trees below. There was nothing to stop him from doing it now, except that he was too cold, too tired, and too miserable to muster the energy it would take to walk back down to the bank and throw himself in.

***

He must have nodded off. Otherwise a Tírfaie would never have gotten as close as this one had. As it was, he just had time to throw himself into a nearby clump of caneberry bushes before the man stepped from the trees less than twenty feet from where he’d been sitting. Scratched and shaken, Seregil peered out through the thorny stalks, watching the intruder stroll up the hill.

The last glow of sunset was at the man’s back, casting long shadows in front of him. All Seregil could make out at first was a tall, broad-shouldered figure, with a long scabbard swinging heavily against its left hip.

The man halted near the tree, then looked around. “Hullo?” A young, deep voice, colored by an accent Seregil couldn’t place. “Don’t be scared, girl. I won’t hurt you.”

Girl? Seregil allowed himself a sour smile. Stupid, blind fool of a Tírfaie, just like all the others. By the Light, he was sick of the whole lot.

All the same, this one had gotten dangerously close, and Seregil couldn’t move now without being heard. Looking quickly around, he found a fist-sized rock in reach and gripped it.

The fellow turned slightly and the light struck his face. He was man-grown but still young by Tír reckoning. His face was strongly boned, and freckled as a trout’s sides. Coarse auburn hair hung in an unkempt mass over his shoulders. A sparse, coppery moustache drooped over the corners of his mouth and his cheeks and chin were thatched with stubble. His battered corselet and worn boots marked him as a wanderer of some sort, at best a caravan guard; at worst, a bandit.

Harsh experience had taught Seregil something of reading faces; this man was not stupid, not at all. All the time he was gazing about, he seemed to have an ear cocked in Seregil’s direction. He knows I’m here. Seregil gripped the rock, bracing for an attack. If he could surprise the man, stun him with a well-placed blow, then he could escape, perhaps even with the sword and that bundle the man had over his shoulder. He didn’t look the sort to travel without food or flints.

But the man just stood there a moment longer, then shrugged. “Suit yourself, girl.” With that, he dropped his bundle and set about gathering sticks and tinder for a fire.

Sprawled on the damp ground, Seregil watched with growing suspicion as the fellow struck a spark with his knife and a flint and kindled a good blaze under the tree. When it was burning well, he rummaged in his bundle and brought out a small iron pot and a few cloth-wrapped parcels. Leaving his supplies by the fire, he headed down to the river with the pot.

It was tempting to make a dash for the supplies, but it was obviously a ruse to draw him out. Seregil stayed where he was, and presently the man came back with his pot and some green ash sticks he’d cut at the riverbank. He rigged up a fire hook with some of them and set the pot of water over the flames. Then he sharpened another stick with his knife, unwrapped the parcels, and fixed a large chunk of yellow cheese and some sausages on the stick to toast.

Soon a mouth-watering aroma spread over the little clearing. Seregil’s stomach, empty these past two days except for river water and what little he could forage, let out a long growl.

As if he’d heard, the man called out, “More than enough for two here, girl. From the glimpse I got of you, I’d say you could use something solid under your ribs. And a blanket, too. I won’t ask to share it with you. I swear by the Flame and the Four.”

Seregil remained where he was, hating the man even more.

“Come now, I know you’re there. That raspberry patch won’t make much of a bower for you when the dew falls.” After a long moment, the fellow let out an exasperated sigh. “No? Well, I won’t force you out, but I don’t fancy sleeping with you lurking there like that, so we’re both in for a weary night.”

Seregil lay still, mouth watering, as the dew settled through his scant clothing, chilling him from the back as the damp ground chilled him from the front. The sausages sizzled on their stick, redolent of rosemary, mutton, and garlic. He hadn’t smelled anything so good since the market stalls at Cirna. By the Light, how long ago? Two years? Three? The aroma reminded him suddenly of Nysander, too. His old master had always had good sausage like that at breakfast, and toasted cheese. And soft white bread with honey and jam.

He ached with hunger now, and something else, too. Something that made his throat tighten and his eyes sting.

It was almost certainly a trick, he thought, blinking away the smoke that had blurred his vision for a moment. He flexed the fingers that had gone stiff around the rock. This was no bandit. This man knew how to wait, how to bait his prey. That was warning enough.

All the same, he could just as easily have come after him. The man knew where he was, and assumed he was dealing with a defenseless girl. Why all the calling and courting?

Seregil wrestled with his doubts a little longer, but the smell of hot food weighted the argument against caution. At last he called out, “What do you want with me?”

His voice came out hoarse as a rook’s; he hadn’t spoken to anyone in days.

“Nothing,” the man replied, lifting the meat and cheese from the fire and examining them closely. “This is about ready.”

Still not looking in Seregil’s direction, he reached into his bundle again and threw something into the steaming pot. A moment later Seregil smelled the sharp, rich tang of tea. Real tea from Zengat by the smell, not the stinking mess of boiled leaves and roots they brewed up here in the wilderness.

“I’ve an extra mug here somewhere, girl. You’re welcome to it.”

That decided it. Either this was a civilized fellow, or he knew enough to steal from such. Seregil stood up slowly, braced to run if the man proved treacherous after all. “I’m not a girl,” he croaked.

The man looked over at him and his moustache twitched in what might have been a grin. “So you’re not. My apologies, lad. You ran off so fast I didn’t have time to make a proper study of you. You won’t be needing that, though you’re welcome to hang onto it if it makes you feel any safer.”

Seregil glanced down and saw that he was still clutching the rock. No doubt he looked ridiculous to the big swordsman, but he kept it anyway.

“Come on if you’re hungry,” the man urged. “I’m not getting up to serve you.”

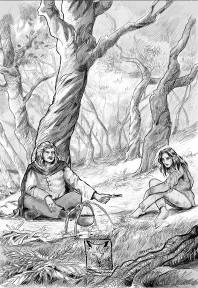

Seregil pulled himself free of the thorny canes and limped to the fire, giving the stranger a wide berth and keeping the fire between them. The man stayed where he was, but leaned over to hand Seregil the toasting stick.

He took it, and watched warily as the man found a cup and tossed it over to him. He caught it easily and set it down beside him.

“Welcome. My name’s Micum,” his host said, resting his large hands on his knees where Seregil could see them, clearly a calculated move to show he meant no harm. Seregil ignored the expectant pause that followed. He gave his name to no Tír.

“I don’t have a knife,” he said at last. In fact, it was all he could do not to gnaw the meat and cheese straight off the toasting stick, but that would have been common, and poor thanks for the hospitality offered.

The stranger drew the knife from his belt and held it out, handle foremost.

Seregil tensed again. If he reached for it, distracted with food and one hand busy with the stick, it would be a simple matter for the other man to grab for his wrist.

He’d hardly finished the thought when Micum placed the knife on the ground between them and sat back. “You’re a cautious one, aren’t you? Though from the looks of you, maybe you have good cause to be.”

It was nearly dark now, but the firelight shone full on his face and for the first time Seregil was able to look him in the eye at close range. Light eyes, he had, bright at the moment with friendly amusement. Seregil snatched up the knife and cut the purse string from his wrist, then carved himself a portion.

“You’ll want this, too.” Micum tossed a chunk of stale brown bread neatly over the fire and into Seregil’s lap.

Seregil took a second look at him, guessing that this move had been a sign, too. This man knew how to fight and wanted him to know it; the scabbard hanging overhead was scarred with use and he had a few scars on the backs of his hands. He was big, nearly a head taller than Seregil, and well muscled, but he moved with a natural, fluid grace. Fine swordsman that Seregil was when he had a sword, he already suspected that this Micum fellow was someone he’d rather fight beside than against. He’d made no move to harm Seregil yet, either, but the evening was still young.

***

“I’ll have the knife back, if you’re done with it,” Micum said, watching the stranger closely without making a show of it. He was beginning to regret his kindly impulse.

Not only was this no lost girl, as he’d first supposed when he’d glimpsing the huddled figure from the road; this ragged, wild-haired fellow wasn’t as young as he’d first guessed, either. No, he was ‘faie—true pure Aurënfaie, too, judging by his build, his high-tone manner of speech, and the southern cut of his rags. What a ‘faie was doing here on the banks of the Keela River, only Illior knew. No gear. No horse. No food. Thin and dirty as a young tom in spring, and just as battered. Someone had given him a proper drubbing recently, and perhaps he’d deserved it. There was a toughness about him that balanced that fine, pretty face, and a hard glint in those cold grey eyes that Micum didn’t like one bit; it was the look of a kicked dog that was ready to bite. He hadn’t given his name like an honest man, either.

And, Micum noted with no particular alarm, he still had the knife. He held out his hand for it, and the bottom nearly dropped out of his belly as the stranger handily flipped it up in the air, caught it by the blade, and shied it at him.

Either the man’s aim was very good or a little bad, for the blade thudded to earth a few inches from Micum’s left knee, the quivering blade sunk a good three inches in the ground. Judging by the fellow’s smirk, this was a message to him, and Micum added arrogance to the rapidly growing list of reasons why he didn’t like this nameless stray.

All the same, he had given the knife back. Micum pulled it free and wiped the blade clean on his trouser leg before cutting his own portion. “You’re an Aurënfaie, aren’t you?” he asked, to see if he could take him down a peg. “Up from Skala, I’d say, by your accent and those rags. You’re a long way from home.”

This earned him a startled look. His guest didn’t look quite so smug now. “I am. I don’t recognize your accent.”

“I don’t suppose you would,” Micum replied, fighting back a grin. “I’m from a little town in the free holdings beyond the Folcwine. Cavish, it’s called.”

“Never heard of it. Is that in Mycena?”

“North and east beyond it. I’ve been working the Gold Road as a guard for the caravaneers. I liked what I’ve heard of the southern lands, and I liked the men I worked for. The caravaneers were full of tales of Skala and her fine cities, so when we got to Nanta, I decided to keep on going and have a look for myself.”

“Just like that?”

“Just like that.”

Suddenly the stranger surprised him again, this time with a smile . “So you’re a long way from home, too.”

Micum blinked. It was as if a completely different person was looking at him from under all the dirt and tangled hair. The hard, guarded look had slipped like a mask, showing Micum someone almost as young as he’d first supposed. He was shivering, too, Micum saw; the hand holding the bread was shaking so badly that the cheese was sliding off.

Micum untied his cloak and gave it to him, still careful not to move too suddenly and startle him. “You’d best wrap up.”

“Thank you.” The stranger accepted it with a rather chagrinned look.

Balancing his supper on one knee, he bundled himself up to the chin as if it was winter, rather than a warm autumn night. With his rags covered, he had a more refined look about him, even with the dirty face. Micum hadn’t had a lot of contact with folk of quality, but he knew one when he met one and this boy was gentle born, whatever his circumstances might be now. He chewed his food slowly, rather than wolfing it, then dipped his cup in the pot and held it to his nose, eyes half closed as he inhaled the fragrant steam.

“It’s been a long while since I’ve had this,” he murmured.

“Got a taste for it from those Skalans,” Micum told him, studying his guest with growing interest. “I’d rather have good ale, myself, but this carries easier and refreshes the spirits.”

The stranger saluted him with the cup, poured out a few drops on the ground for whatever gods he owned, and then sipped delicately at the brew. Micum filled his own cup and they sat in silence for awhile as the stars came out overhead.

***

As the tea spread its comforting warmth through him, Seregil let out a contented sigh. Micum’s cloak was warm and smelled good. The man had given freely of his food and offered him no violence. As the comfortable silence stretched out between them, he allowed himself a second look at his companion. Micum wasn’t handsome, certainly, but he had a good smile and a steady, easy manner that put Seregil at his ease. It was tempting, so very tempting, to like him.

More fool, you, the inner voice taunted.

Ignoring it, he arched a wry eyebrow at Micum. “So you don’t mean to rob or rape me, after all?”

“Is that what you thought?” Micum asked, insulted. “And rob you of what, pray tell?”

“I’m sorry,” Seregil said hastily. “I ask your pardon. I haven’t had much cause to trust anyone for a long while. But tell me, why did you come up here after me?”

The man looked as if he’d asked why the sky was blue. “I saw you from the road. You looked like someone who needed help.”

“A girl who needed help,” Seregil reminded him.

Micum shrugged. “It makes no difference.”

Seregil looked into that earnest face and felt his resolve slipping again. Stop it! He’s a Tír. Nothing but a Tír ...

“You don’t believe me?” Micum bristled again.

“Oh, I do,” Seregil assured him, looking down into the fire to avoid that earnest gaze. “I do.”

“Then I don’t suppose I might know who I’m talking to?”

Fool! the voice shrieked as Seregil leaned over and offered his hand to the man. “Forgive my rudeness. I’m…” He faltered as Micum’s big, rough hand closed around his. The man’s grip was warm, firm, reassuring, and came in the company of a ready smile. Seregil had to swallow hard before he could finish. “I’m Rolan. Rolan Silverleaf.”