heart that deviseth wickedness, that’s Wulf Christopher.” “But you forgot lying,” said Bruce. ‘The order is eyes, lying tongue, then hands, then heart.’aBl ... “So he skipped lying,’ she said. “So he doesn’t mind breaking the order.”

117

“Why make it easy?” Bruce mused, tilting his head. “Funny thing is lying is here twice—the lying tongue and then the false witness that uttereth lies.”

“Right,” said Betty. “If I had to guess I’d say that’s why you have the odd ‘six or seven’ confusion at the beginning. Lying is two-in-one. Maybe a private lie, versus a witness, a public lie.”

“Hm. Then what?” Bruce mused. “Feet that are swift in running to mischief. Just like you guessed, feet.” “Feet.” They stared at one another, waiting for lightening to strike.

“Not a thing,” said Bruce.

“Search me,” Betty shrugged.

“Great,” Bruce chewed his lip. “And there’s no guarantee it’ll be just one person. People get hurt around his targets. Think. Feet that are swift in running to mischief.” “Someone Emil has a reason to hate.’®

“Connected to him personally, in some way. Like the cops, and Christopher by extension.”

“Who else? What next?”

My eyes on the stars...

Bruce turned around and looked past Betty. The kitchen in the condo had a bar over the counter, and above the bar was a space in the wall so one could serve guests in the living room. And in the living room, he could see the television. “My eyes on the stars,” muttered Bruce. “Feet... running ... to mischief..■_ _

Betty looked at him. “Hey, partner. Whatcha got?” My eyes on. the stars...

“Up a... Hill..The Hulk bounded into the living room and hit the mute button, busting the remote in the process. “Like a politician, running, like a crooked— ”

“What?’*

“Something I read about Christopher, God, I forgot his connections with—”

Senator Hill was still talking to Mario, and they were running another clip, and there it was, and Hulk turned the volume up high. “Look!” gjjSMy eyes on the stars, my feet on the ground!” And the flag was waving and people were cheering. Emil, you’re a bad, bad poet.

“The senator,” said Betty.

“Terence Hill made his Fortune, before becoming a senator, as a secret partner with Wulf Christopher. Rick wanted to talk about that on his show but they wouldn’t let him. Is this show live?”

Betty stared. “Usually. Oh, no, Rick and Mario!” The Hulk grabbed the phone, clicked it on, and punched eleven digits. After a moment somebody answered. “Rick Jones, please, it’s an emergency.”

“I’m sony,” came the female voice on the other end. “But he’s already left.”

The Hulk stared at the television. “But the show’s on the air.”

“Yeah!” came the chirping answer. “We all get off early today because we filmed it on delay. The senator had to make a flight.”

Bruce felt his chest tighten. “Delay by how long?” “One hour. Can I get you anyone else?”

Swhat airport?”

“What?”

The Hulk yelled. “What airport Kennedy, LaGuardia, or Newark?”

“Did you say emergency?”

“Yes. Please ”

There was a pause and a smack of gum. “Limo went to Kennedy. Plane takes off at seven.”

The Hulk clicked off the phone.

There was a sound, an electronic chhp from the study.

The Hulk walked into the study with the handset, already dialing another sleven-digit number.

A familiar, female voice answered. “Jo Carlin.” “Jo?” Bruce looked at his computer screen. He had e-mail. Anonymous e-mail. “Jo, I’m headed for the airport. Senator Hill is gonna have trouble.’a He clicked on the message beacon and the message opened up. He stared:

TOO LATE.

K^yJo?” Bruce called. “Jo, are you there?”

The line was dead. Bruce clicked the phone off and dropped it. Within seconds he was out the door and in the air.

3 am not resigned, Sean Morgan thought, to the shutting away of loving hearts in the cold, cold ground.

The fair-haired colonel stood still next to Margaret. Morgan, his coat flapping in the chill wind. The priest was reading from his Bible, speaking softly. A large black box that held his only son was being lowered into a hole. Morgan heard nothing, and stared ahead into the distance.

Give me this, God. Give me this. Take this away from him and give it to me. Replace us. Please. It was a crazy thought, a stupid prayer, answered by only the wind and the soft murmuring of the priest. The Edna St. Vincent Millay poem continued in the back of his head: So it is, so ii shall be, so it has been, time out of mind.

Morgan glanced at Margaret. She seemed to sense it and looked back with what could only be received as an icy stare. They had not been this close in years. Margaret's hair had begun to go a bit gray at the temples, he noticed, but she was still lovely, her red hair pulled back and set off by the black hat and veil. She whispered, and as she did her face softened into a sullen frown, glad you could make it, Sean.’ ’

He could not tell if that sounded bitter or not. He tried not to care. “Thank you.” He could think of nothing else to say.

‘ ‘I want this to be over,’ ’ she said flatly, and then he saw tears well up, and she sniffed. He blinked severa’1 times.

“Me, too.” Morgan felt awkward, his limbs heavy and stupid, as he reached out his hand and took hers. He was shaking. For a brief second it felt as if she was going to swat him away but then her hand clasped his in return. “Me, too.”

■“I want it to be over and gone,” she whispered. “Over and not even real.”

“I know,1’ he said. “I didn’t, uti,” the words were coming on their own, meaningless, “I didn’t see him at Christinas, I was—” Why did he say that? Why was he starting her side of an old argument?

“Please. Sean,” she sniffed. “Not now.” And she could have said, You didn’t see him a lot of Christmases. You didn’t see him a lot, period.

His voice cracked and he whispered, “I’m sorry, Margaret,” and now she was in his arms, crying into his chest, and it was the first time he had held her in ten years, easily. “I’m so sorry.” He looked... so much like'you. So much like both of us. So much is gone, Margaret.

And she was crying into his coat and he was holding her, smelling her hair, that smell he hadn’t smelled in years, and he was holding back tears for some reason, some awful, evil reason. The world was gone around them, and they floated in cold space, alone, terribly alone. Even in one another’s arms, alone.

There was a strange sifting sound, dirt falling off the edges of the grave and onto the metal coffin. And over the end of the priest’s speech, a humming sound, alien to the cold cemetery.

But not alien to Morgan. The Green Beret looked up from Margaret’s shoulder and saw a hovercraft topping the hill, moving slowly over the graveyard. Oh, no, say it isn’t so...

Margaret looked up. “Sean?”

He let go of her and stepped back, and for a brief moment wanted to say something, anything that could possibly explain. But he saw her eyes, that cold stare again, that stare he remembered now and that burned into him like a hot brand. Sean Morgan looked away, at the hovercraft that now hung a few yards off the interment site, and hung his head in shame.

‘‘I have to—’

‘Go,” she mouthed. She wasn’t crying anymore. Morgan bit his lip and turned and began to walk towards the hovercraft, certain that he had just seen something gone for years come to life, and die forever.

“Talk to me,” Morgan said, once the hovercraft was in the air. He felt the cool veneer of professionalism slide over him like a garment.

An agent named Russel Banks sat across from Morgan. “Terribly sorry for the timing, sir.”

“Just tell me what the problem is,” Morgan held up a hand. They wouldn’t do this to him if it wasn’t neces sary. He hoped.

“We have a situation at JFK, Colonel.”

^jWhat?”

“Jo Carlin radioed Gamma Team that the Hulk suddenly went crazy. He said he’s headed for the airport, and he’s going to attack a plane carrying a United States senator.”

“What?” The hovercraft had already made it to the docking bay of the helicarrier.

“You can listen to the traffic if you—’

“Right.” Morgan grabbed the headset off of one of the other agents. He fastened the mike and spoke as he rode the lift. “This is Morgan, what the hell is going on out there?” He turned to Banks, who was following, but barely able to keep up: “Where’s Carlin?”

“Like I said, she and Gamma Team headed for the airport.”

What seemed to be a thousand voices were speaking at once in Morgan’s ear.

“... got rignt past me, Jo, Jesus, he’s fast...”

“... police and media choppers, please disperse ...” “... nearly knocked that reporter out of the sky, I’m surprised that...”

'‘t .. get those choppers out of here before they hit one another?”

Police? Media?

“I can’t leave you people alone for a second,” Morgan liissed. The two men burst into Morgan’s office and switched on a television screen on the wall across from his desk. Sure enough, there was a news report. All hell was breaking loose.

On the screen he could see reporters and police cars swarming the field. A cheery woman was announcing how exciting it was that the Hulk had announced his intention to down a plane.

“How’d the media get this?” Morgan turned and looked at Tom Hampton, who ran in the room. He waited a half-second for a response, then signed the question.

“Something went wrong,” Tom signed back. “Someone below was monitoring Jo’s call, and it was tapped by the media.’’

. ■ “What are you saying, they heard what Jo heard?” Tom kept signing but switched on his voice modulator as he brought up a second screen and pulled up the GammaTrac. ‘ ‘They heard what Jo heard, and heard her call out Gamma Team.” The screen zoomed down to the airfield, and there was the blob of green labelled hulk, moving towards a white unit that seemed to be taxiiing.

The phone rang on Morgan’s desk and Banks snapped it up.''-“Betty Banner on line one.”

Intercom,” snapped Morgan. “Mrs. Banner, we—” “Mr. Morgan this is a mistake. Bruce is trying to save him! The Abomination is out to—”

Morgan looked at the GammaTrac and at Tom. “Is Blonsky anywhere near the field?’ ’

Tom shook his head.

“Wonderful,” Morgan spoke into the mike: “Jo, this is Morgan, talk to me!”

The mike crackled and Jo came in. He could hear the hum of the hovercraft she was riding. Shots were being fired behind her. ‘‘Colonel! God, it’s a mess out here.” “What’s happening?”

Jo, the woman on the television, and Tom Hampton’s voice modulator all answered at once: “He’s going for the plane.”

When the Hulk sprang from his condo towards John F. Kennedy Airport he was still trying to figure out how he was going to guess which plane would be Senator FLJ’s. Beyond that, who cut my phone line? There was someone in SAFE who didn’t belong there. There was someone pulling a few too many strings.

The gamma giant rocketed through the air and landed on a freeway, and leapt into the air again. Cold wind whipped through his green hair and stung his eyes. He could cover at least a mile with each leap, more if he really put his legs into it. The Hulk used to drive the army crazy leaping all over the Arizona desert, and more recently did the same thing to his SAFE tails. Before everyone found out where he lived.

Land. Smash. Another leap. Hopefully, he would spot Emil on the field before he had to find the plane. Seven

o ’clock. It should be almost seven now. He berated himself with each leap that he might be going off half-cocked, that the field might not be the answer. Emil might decide to crush the limo, instead, or attack the senator at the airport. But something told him the drama of a downed plane would be just too attractive. Too attractive not to check, at least. (Too late.)

After a few more leaps he saw the sprawling airport, and past the buildings, the field itself, barriered by tall fences and topped by barbed wire. As he leapt into the air again he looked around for Emil. Where are you?

Only then did he notice the vans. At least twenty of them: cable, radio, broadcast television station vans, all corralled around the fence like a wagon train waiting for an attack.

Waiting for an attack..

Police lights caught his eye and he saw the squad cars swarming onto the field, headed for the east-most runway. What the hell are they doing?

There were three planes taxiing, all runways lined up. Two of the taxiing planes he dismissed; those were jumbo jets. The third was private.

Bingo.

Something leaden and heavy struck the Hulk in the back. He was being shot at. His trajectory was finished; he dropped to the ground and prepared to leap.again. The small plane was just beginning to take off.

“Hulk!” A hovercraft zipped from behind. “Turn around and go back!” On the hovercraft, a female agent held a megaphone and the agents behind her held several large guns.

Bruce tried to yell. “Jo! Look for Emil! He’s got to be here!” He leapt into the air and barely held his direction as several large-calibre bullets slammed him in the side. He growled in pain but kept himself aimed in the direction of the jet, which now had lifted about thirty feet off the ground and was still climbing. ‘Radio them!” he yelled to Gamma Team. ‘Warn them!iT“

They couldn' t hear him, because they were shooting at him. The Hulk twisted and flipped, heading downward, when he nearly collided with a media chopper.

The Hulk looked up and saw the plane in the air, heading out, and two more hovercrafts zipped around him and opened fire. Bruce took to the air, flying past Jo’s hovercraft. He aimed straight for the cockpit of the jet

Within seconds he was alongside it, flying fast, and the pilot looked out and saw him and was shouting some thing into his headset. Bruce pointed at the ground. He pointed at the ground again. “Put downl” he shouted, pointing. “Down!”

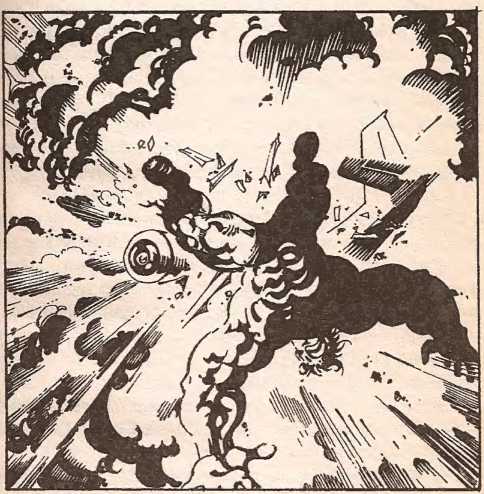

The pilot looked at the Hulk and was still yelling into h headset when Bruce felt himself propelled violently backwards, as the plane exploded in one great, fiery blast.

Not far away, exposed for all the world to see if they bothered to look, under a tiny tree by the fence on the other side of the field from the circus of vans and helicopters and hovercraft, the Abomination put away the detonator and listened to the radio. And as he listened to the reports (“Oh my God he blew up the plane...”), he laughed. The feet were through running, the false witness had begun. Two down in one fell swoop.

He couldn’t stop laughing.

After a moment the Hulk hit the ground, digging a fifteen-foot trench. When he crawled out he heard the laughter, not a hundred yards off.

j"i et’s talk power.

L Power is a steam train seen for the first time when all you’ve ever witnessed is a horse and carriage. Power is a lever when all you’ve ever used is your knees. Power is an arrow flying through the air at someone who has, up to that point, thought you had to stand before a creature to strike it down.

Power is anger, real anger, when up to then you haven’t really had the angry man’s full attention.

Power was the Hulk, a green rage flying through the air at the beast.

And the Abomination was thrilled, absolutely thrilled, to have finally gotten the Hulk’s attention. The Hulk could tell, because the demon was laughing at him.

All right, Emil. You’ve pretty much ruined it for me now. The Hulk saw the Abomination smiling at him that long, alligator mouth curling like a Greek mask as F.mil put something away in his coat and got up, almost casually. Emil moved casually and fluidly, shaking his finned, red-eyed, demon head. He held his hat and his coat was flapping. He was beginning to laugh, and as the Hulk rocketed towards Emil, Emil almost imperceptibly began to speed up. He stepped into the satellite parking area, moving between a pair of matching Lincolns.

All those people back there. A plane equipped with one senator and a host of staffers, down, and the whole world thinks I did it. You must really be proud of yourself.

The Hulk was a missile, arms outstretched, hands locked like claws, ready to grab onto whatever ended up in his grasp, and as we zeroed in he saw Emil leap into the air.

The Hulk hit the ground on the other side of the fence that surrounded the field. The Abomination was leaping

and removing the long, brown coat he wore, the hat falling to the side. In the distance Bruce could hear the helicopters and sirens. He looked over his shoulder and saw the hovercars zipping across the field, intent on catching up to him.

Something slammed into a car with the ripping force of an ICBM and the Hulk looked back to see a Mercedes explode. He saw the roof of the vehicle pulled downward, windows busting out, the entire vehicle collapsing like a tent into the hole in the asphalt left by the Abomination as he dove through it. The Hulk bound into the air, flipping, pointing his feet downward, and followed. The crumpled Mercedes disappeared from around him and he fell in darkness, underground once more.

The hole burrowed by the plummeting Abomination ended and Bruce landed, sinking his feet into the wet concrete of another sewer tunnel. He looked ahead of him, then in the opposite direction. In the distant gloom, he saw the Abomination standing, shrouded in shadow and half-hidden by the comer, waiting for him, “Emil!”

The figure disappeared, and something like laughter, gurgling and raspy, echoed through the tunnel.

The Hulk stood still and breathed. Overhead, in the distance, helicopters and hovercars circled. He closed his eyes for a tenth of a second and let the vehicle sounds disappear from his mind. Deep within his breast a savage beast was growling. This entire fiasco with Emil was too complex for the savage to understand. The savage never would have been in this situation.

Not complex. Simple Get him.

Bruce felt a wave pass over him, a tingling arc charging through gamma-irradiated muscles, and he heard the laugh of the Abomination. The beast told him to move. But it was Bruce who did so.

It would be so much simpler if I were still that mindless, savage Hulk. Hulk would smash, and smash, until nothing was left. Hulk would not be fooled by ploys or computer messages or idiotic poetry or attacks on his sense of guilt and honor.

The giant began to move again; less than a second gone, and his legs and arms began to sweep in long green arcs.

But it is not simple. It will never be simple again.

Long, green arcs, hands reaching out to clutch pipes as the Hulk burst down the tunnel. Slithery creatures stood up on hind legs and swiveled their heads, watching the green blur moving through the dimness, feet slamming against wet slimy concrete, cymbal crashes in the symphony of drips and drops in the murky shadows.

Around a comer, the Hulk sped, spinning as he turned, realigning himself, and now in the distance he saw Emil again, stopped momentarily. About fifty yards away stood the demon, feet balanced on a ledge, and the tunnel seemed to open out. The Hulk saw the shimmer of artificial light coming into the tunnel from the space beyond. Emil looked back and saw the Hulk, and both men leapt at once.

The Hulk sailed into the air, past the mouth of the tunnel through which Emil had just flown, falling. Emil had gone farther out and now sailed downward. The Hulk saw the creature’s legs and grabbed on in the flickering red light. The two gamma giants travelled twenty feet, falling, the Hulk wrapped around the legs of the Abomination.

Emil looked down at his feet and kicked.) ‘-Finally we have it out.”

The Hulk cursed as the scaly foot collided with his jaw. He looked down just in time to see a network of metal platforms and walkways, before the tumbling pah-collided with the first one.

Metal shrieked and gave way, the gamma giants tearing through girders and steel tubes. The Hulk felt the rail-ng of a walkway below flatten out on either side as he came to a slamming stop crosswise on the metal, and he

winced again as Emil’s weight came down on top of him.

Bruce looked around quickly at the red-lit room. They ;eemed to be inside a great, concrete barrel, lit here and there by a shimmering light, metal walkways travelling from tunnel opening to tunnel opening, here and there the monotonous rust and slime interrupted by a metal wheel or meter. They were in some part of the water treatment system, a gateway of sorts.

Emil stood up on the walkway and picked up Bruce by the hair. Bruce felt the Abomination’s kick in his ribs and he shot out his fist, felt it connect with razor teeth. He fell backwards with the force of Emil’s kick, taking out more metal as he went, grabbing onto another walkway. Bruce slammed into a walkway and the air rushed out of his lungs as the metal pressed into his chest, but it did not break. Now he looked down for a brief moment, saw the pool, thirty or so feet below, swirling and murky. This is treatment? The Hulk heard the metal groan as he flipped over, throwing himself back up, finding the railway next to Emil and flipping again, landing both feet in Emil’s chest. Emil tumbled backwards, but managed to get a spring off the metal girder as he passed, and he shot out to the concrete edge of the barrel. Emil caught onto the lip of another tunnel and looked back, hanging there, and shouted across the chasm.

“Dr. Banner, this is so much fun. ’ ’

The Hulk sprang, landing on the wall, nands digging into the concrete and catching metal underneath, and he held himself in place, pounding his fist into Emil’s solar plexus. “You killed them back there, Emil. You killed them to make a point. You’re insane!”

Emil grunted with Bruce’s blow and laughed, let go of the edge of the tunnel and let himself slip beneath the Hulk on the wall. Bruce looked down and saw the Abomination slide along the dirty concrete, grab a ladder, twist, and spring,, and the demon was sailing again. A clawed fist caught nim in the jaw as the figure passed, and Bruce twisted around. He brought his free hand up to his mouth and felt the flow of blood, so rare. F.mil landed with a crunch at the lip of another sewer tunnel, on the other side of the barrel.

“Heh,” growled the demon. Bruce hung there, bleeding, watching Emil clinging to the twisted metal, the red lights bouncing off deep green, scaly skin, and he saw the insanity. It was evident even in the curious twisted way Emil hung there, like a gargoyle, or a gamma-irradiated ape, enjoying the show Bruce was putting on. “You idiot,” said Emil, hanging there, breath rasping. “More fun than a barrel of gamma giants, no? You and I could keep this up for hours.”

Bruce shook his head. "Emil—”

“We can be gods, in our own way, bashing one another’s head into walls and feeling almost nothing. Doesn’t it get you going, Hulk? Doesn’t it make you thirst for more? To know that only someone like myself can give you this kind of workout?”

“You’re wrong,” said the Hulk. “There’s always the Thing.”

“Cheesecake,” said the Abomination, and the Hulk was in the air again, fists outstretched, a green missile. Emil threw up a hand and deflected Bruce’s fists upwards. Bruce’s body rolled, but before Emil could deliver a blow the Hulk brought his knees square into Emil’s chin. The concrete barrel shook as Emil’s head busted the concrete behind him and he lost his grip on the wall. They began to fall again.

Twisting and spinning in the air, this time the metal girders they hit barely squealed as the gamma twins tore through them. The Hulk saw his sparring partner smiling and laughing, and suddenly the air turned to liquid as they hit the pool below.

Two tons of dense green flesh hit the murky water and plunged, and the Hulk opened his eyes under the water and saw only blackness, the slightest hint of red light ?nimmering through, as he and Emil sank another fifteen feet.

The Hulk’s feet hit concrete and he slipped and settled onto the slimy ground, limbs flailing through the stagnant morass. He saw the shadow of Emil, settling to the bottom with him.

Emil scuttled backwards for a moment, like a crab, and the Hulk looked around him. Why Emil, you take me to the nicest places.

They were at the bottom of the barrel, a Lwenty-foot circle surrounded by curving concrete walls, laced with a hundred pipes of unknown origin or use. Something slick and primitive brushed by Bruce’s leg. He looked down, then back at the shadow where Emil had been. In the water swam shimmering silver things, snapping and slithering, as if someone had created a dark reflection of a dime-store snow globe and shaken it.

The shadow had moved. Bruce cursed and looked around, and then Emil had him, coming from above, claws grabbing his throat, clawing at his eyes. The Hulk clamped his eyes closed and grabbed onto Emil’s arms, trying to slam the demon back against the rusted metal wall, but he was moving through molasses, and the two merely floated back.

The Hulk had run into this problem before. There were benefits to weighing a ton and having extremely dense, thick, quickly-regenerating skin. He could count those benefits on a hand, and Doc Samson advised him to do so just about every session. Buoyancy was not among them.

Bruce began to use his elbows, slamming back against the Abomination, one side after another. The slithering thing below moved past his feet as he danced, causing the thick water to shimmer, the slithering silver creatures flying in all directions. Suddenly Emil was slipping, and had to use h s arms to right himself. The Hulk pushed away, let his tremendous weight settle to the bottom, and spread his legs, spreading his toes out to cover as much area as possible. He felt mud, alive with tubular, squirming life, squish between his toes, as he forced his toes down and ground them into the concrete. He lowered himself slowly, thick water flowing around him, and then let go. The dense body began to move, the Hulk’s leg muscles springing up, stretching out, and he let go of the concrete and felt the water sailing past him.

Sure would hate to end up on the bottom of the ocean, thought Bruce. I’d end up having to walk to shore.

The Hulk burst through the black surface and the red light filled his eyes. He breast-stroked to the edge and grabbed a large pipe where it was fused to the wall and began to pull himself up, then yanked hard, lifting himself fully out of the water. In the end, he was nimble. Big and dense, but nimble. The Hulk found his place at the mouth of a lower tunnel and looked back down at the pool of sludge.

The black water was trembling in the red light, betraying movement below. Bruce stared, waiting for the Abomination to resurface. Briefly, Bruce considered jumping back down there, but decided scuffling in that goo was not worth it. He would wait.

Black water burbled and waved and something burst from the surface, a dark green set of head and shoulders. Emil held back his head and roared, holding up his arm, and in the red light Bruce saw that he was not alone. Something bone white and thick, a snake of some sort, ten inches wide easily, had wrapped around Emil’s chest and Emil had it by the throat, a long, fanged mouth hissing and snapping at him. The albino snake snapped again at Emil’s face and Emil began to pull. Bruce saw the thing slowly stretching with Emil’s arm, uncoiling from around the Abomination’s scaly chest. Then the Hulk heard another sound, as the snake uncoiled completely, held below the jaw by one green claw.

Emil was laughing. The Abomination’s red eyes stared into the pink eyes of the albino serpent and his laughter howled, profane and deadly. The creature writhed in the red light, the white, scaly body dancing on the water like a pressurized hose, black water dancing all around the two, and Emil looked up at Bruce.

“I am as one gone down to the pit,’ said Emil. “You can never catch me here.”

Suddenly black water flew and the Hulk saw a white-scaled body flying towards him, a fanged mouth spitting and tumbling as Emil flung the creature up at Bruce’s face. Bruce held up a hand and felt the creature clamp down on his wrist, causing just enough of an indentation to hold on and begin to wrap itself about him. Bruce cried out in surprise and blinked at the black water in his eyes. The creature was huge, and now it wrapped around his ankles. The slime on the bottom of the tunnel’s mouth gave below his feet and he fell backwards.

The Abomination was still laughing. The Hulk looked across the barrel and saw Emil at another tunnel mouth. “You never cease to amuse me, Hulk! I play the mne and you dance. That is what you are, Hulk! A house slave, a performer. You were better off stupid, because now you amuse the world and you have to know how useless you are.'”

Stop wasting time, Bruce thought, and he squeezed the serpent and slammed it against the wall. The thing snapped at him and he felt bones snap and saw the pink eyes roll. “Emil, I’m tired of—” .

Emil’s laughter echoed from the tunnel entry and Bruce shook his head, sliding the serpent off of his body. His cotton pants were practically black with muck. Enough. The Hulk sprang across the barrel and into the tunnel. He saw the shadow of the Abomination, moving faster now, laughing all the way. Bruce began to run.

Rats and snakes running for their lives, spider webs tangling in his hair. The tunnel proceeded nearly a mile before a turn, no possible exits, and Bruce doggedly pursued, hearing the cement thunder as he passed by. Putting me through paces, amusing himself with my perfonnance. What is this, Emil? What is your game?

The tunnel ended a few hundred yards ahead. Bruce saw a ladder lit by a red light. He slowed as he got closer, looking around. A trench of muck, an indentation in the tunnel, began a few yards before the end, and Bruce hopped over to one side and continued running along the seven inches of semidry floor. He reached the ladder and looked up.

There was a portal, shut and cobwebbed. Bruce reached up and touched it and realized that no one had gone through there for years.

The water in the trench moved, and Bruce looked down. A scaly, demonic giant began to sit up, black water and silver worms flowing off his scales. He sat there at Bruce’s feet, and the water ran away from his glowing red eyes.

“Hm,” he said. “Dead end.”

“What is this, Emil?” You could have escaped at any time. “What are you doing?”*

“Bruce,” Emil said, a serpent in the pool. The red eyes blinked away the water and he sniffed. ‘I’m really going to miss you.”

“Let’s go, Emil,” Bruce sneered. “That’s enough.” He moved towards the trench where Emil sat and the Abomination looked up.

“Go? Oh, absolutely. The only difference between us,” he said, “is you have no idea of the extent to which I’m willing to go.”

Emil sprang again, catching Bruce in tne chin as he smashed into the roof and sailed. The Hulk staggered back and looked up past the falling chunks of concrete and rusted metal and saw light and air, heard running water. Emil had led him to the surface. Bruce sprang quickly through the hole Emil had left. I’m not losing you this time.

Bruce went twenty feet in the air and began to fall, back and saw Emil on the-—tiles’! The Hulk set down on slick tile and shuddered. There was white tile and metal Furniture everywhere. Someone began to scream. Not the surface. Not quite. Just a much more inhabited part of the underground. They were in a large, circular room about an eighth of a mile in diameter. Scattered throughout the area were people, young, old, families, all admiring one another and various brightly-colored purchases. All around the perimeter were the familiar corporate logos of a dozen different fast-food eateries. He heard high heels clacking on stone and saw a man and a woman scrambling Up a wide stone staircase. Above the staircase was a sign: WELCOME TO THE MOLE COURT.

Great. There had to be a hundred people here, scarfing food in a safe, air-conditioned underground environment. And the Abomination had just burst among them.

Something rumbled and ripped. Emil roared and the Hulk looked back in time to see a table flying at him, a massive, white, formica-topped table, chunks of concrete and mesh dangling from the legs where Emil had tom it free. The table smashed into the Hulk and he batted it aside with his hand, sending it flying, then he gasped, followed it with his eye.

The table sailed, spinning toward the far comer. Bruce yelled in terror as a sandy-haired kid looked up from a plate of kung pao chicken and a comic book and opened his mouth. The kid hit the deck as the table sailed past him, the dangling mesh swiping a piece of white concrete lined with tom linoleum across the tabletop, sending chicken flying. The table slammed into the granite wall on the other side with a massive harangue, right next to the Insta-Wok, and the neon sign identifying that particular establishment sputtered in electronic torment. The Hulk watched the kid scramble towards the staircase, turn back, grab the comic, then hightail it out of there, fanboy dedication at its best.

Got to get him out of here, the Hulk thought. He saw the Abomination tearing across the food court. People were beginning to run, some for the exits, some in the wrong direction. Madness in pinstripe.

The Hulk bounded towards the Abomination, looking down. God, so many people to be avoided. Someone howled in pain and Bruce saw the claws on Emil’s feet dig into a man’s leg as Emil trampled him and the man rolled out of the way.

“Never," cried the Abomination, grabbing onto another table. “You will never know the extent to which I am willing to go!” People got out of the way and scrambled as Emil grunted and began to tear another table out of the floor.

The Hulk snarled as he hit the Abomination with both fists, flying into him, both of them toppling and slamming against a counter. “To do what?" he cried. “You want to have it out, you want to destroy me, let’s do it, but not here." He had Emil pinned beneath his legs and was pounding his fists into Emil’s face, and Emil was swiping his claws at him. A couple connected and Bruce felt green blood fly from his cheek. -

“Here is perfect!" Emil growled. “I don’t wantjow.” Emil rolled to the left, bringing the Hulk with him, then rolled to the right forcefully, and they tumbled over. Emil was on top, clawing at the Hulk. “I have no intention of killing you. We could run across the city duking it out, and I might have to hurl you into a volcano before we actually die. Don’t you understand, you fool? I want to crush you by crushing everything around you.” A claiw swiped Bruce’s lip and tore slivers of green flesh away. “I want you to know how useless you are, how meaningless.”

“And wnat," Bruce growled, bringing up his knees, “pray tell, are you?” He kicked, hard, and Emil sailed backwards across the court, slamming into one of the reinforced, tiled columns that littered the place.

Emil was on the ground, chunks of tile and plaster falling on his head. The column buckled a bit and then something in the roof began to sag. Emil stood up slowly as Bruce moved toward him, and all of the sudden he was a performer, wiping plaster off himself in a dramatic gesture. He curtsied and spoke slowly. “Haven’t you learned yet?” The Abomination stepped to the side, looking around. ‘I am an Abomination.”

The Hulk saw what Emil was about to do and shouted, !No!” at the same time that Emil reared his arm, stepping back further, and howled. Bruce watched the dark green arm drive through the column, taking out a four-foot chunk of girded concrete and tile. He threw the chunk at the Hulk and Bruce felt it collide with his face as he flipped backwards with the force, flying through one of the fast-food counters. He blinked and found himself buried in the ruins of a shiny metal kitchen, steel counters and trays and grills wrapped around him.

The Hulk heard a new sound, a terrible whine, and he looked up and saw plaster falling. Oh no. He roared and threw the stove to the other side, desperately hoping the proprietors were nowhere near, much less healthily insured. He felt something like rain, concrete and plaster rain, and he stood up and saw pieces of the roof falling, playing the tabletops like a xylophone.

Bruce looked over the ruined counter and saw Emil at another column. He was tearing it loose, and already the roof was sagging. “No!” Bruce jumped over the counter and felt the wind of the next meter-long piece of column fly past him. “Please, it won’t hold, these people...” They were falling all over themselves at the staircase, a bunch of them pushing into a doorway next to the restrooms where a sign blazed hre exit. Too many. They were jammed in. The lights began to fail, blinking like an oddly-timed strobe.

Emil brushed his hands, wiping off the plaster. He went over to one of the tables and looked under it to see a man in a suit cowering there. The man had brown hair and was wearing the remnants of his salad. The Hulk stopped moving when Emil grabbed the man by the arm and hauled him out, picking him up and holding him aloft by the collar.

“Emil!” Bruce looked around, running to one of the columns. The space where the chunk had been tom out was getting smaller. There had to be a lobby, an entire office building above them. This place was going to flatten. “Please!”.'

Emil held the man aloft and took the man’s arm, and the man howled in desperation. “Hush,1' Emil spat. Then, he looked at the man’s watch. And dropped him F.mil looked at the Hulk. “I have to go.”

“The roof!” All the people. The people above.

“Handle it,” said Emil. “You can do that, can’t you?” The suited man surveyed his arm presumably to assure himself it was still attached, and joined the pack at the exit. The group was moving, but slowly.

Emil leapt into the air, a green streak, and he tore through the ceiling and was gone. Chunks of plaster and more concrete flew as he passed through.

The Hulk grunted, holding the column, staring at the other one Emil had destroyed. “People! This roof won’t hold!” The lights blinked off and on again, more rapidly, and some of them gave, sparks flying. “Take the main' exit! Go!” In the distance he heard the sound of sirens. He waited, holding the column. Tons of material pressed down on the incredible Hulk as he wrapped his hands underneath the column and stood, watching the people scrambling out.

The lights went olack and a system of red lights sparkled and whined into prominence. The roof groaned again, and the Hulk saw with horror that the two parts of the other broken column were just beginning to touch now under the weight. Go ahead and admit it, this one’s coming down, too.

No more screams. The people were gone. Sirens howled far out of the tunnel and the court was empty and. he hoped, so was the lobby above. He looked around, preparing to let go, to burst out, try to find the way that would do the least damage. He breathed once, plaster fog filling his lungs, and began to relax his fingers. Then he heard the cry.

The Hulk felt his neck muscles straining, felt as if green blood vessels were about to burst through his skin. He blinked the sweat and plaster from his eyes and looked in the direction of the human sound.

There was a child, a boy, about nine. He was lying at the bottom of the stairs, one blue-jeaned leg horridly twisted and swelled. He was grasping at the stairs, trying to haul himself to the next step.

Something above Bruce cracked and howled. The boy yelped as a piece of plaster smacked him on the shoulder and he shook his head, determined, fighting, and crying all at once.

You and me, then, the Hulk realized. You and me.

He leapt. The column gave. The Hulk landed over the boy, a human tent, and curled, his back stiff and high like a cat. He brought his head and knees close and felt the boy curled within him, felt the small heart beating against his knee. He opened his eyes and saw the child, silent, staring into his eyes.

And in one cacophonous howl, the roof collapsed.

Morgan leaned-against his desk and sighed. This was turning into the worst week of his life. ‘What the hell went on out there, Jo?’ ’

“He downed a plane,” said Jo. She shook her head as if she couldn’t believe it.

“Mhm,” he nodded. He looked up at the screen across from the desk, which showed the Hulk jumping into the air. ‘ ‘He gets past Gamma Team, without, I might add, too much difficulty. He jumps for the plane. It’s fuzzy there. ’ Morgan noted. The video was grainy, but Morgan could see Banner leaping up, arm outstretched. The angle of the shot was such that he disappeared behind the nose of the plane. Then the explosion.

“That’s not right, ’ said Morgan, shaking his head.

“Sir. S’ " ~

“I can’t tell if he even touched it,” Morgan snapped.

“What else can we believe?”

Morgan turned around and circled his desk, and sat down. He picked uj his coffee cup and studied it. “Jo, you’ve been trained lo follow gamma threats and study them and catch them. If the Hulk were going to down a plane, is this what it would look like?”

She stared at him, then back at the video. Jo picked up a remote and ran the video back and froze it at the blast. The plane sat in midair, the >iose flying apart. “An explosive?”

“That’s what I’m asking, shouldn’t we be seeing the Hulk tearing through the fuselage or an engine or something?”

“Maybe he’s not that predictable.”

Morgan stared at his desk. “No, he’s not. Becausc an hour later he crawls out of an evacuated building with a nine-year-old in his arms and hands him over to the po-

lice. And the Abomination was there. Witnesses say Blonsky tore the place down and the Hulk was there to help stop him.”

“Others are saying it was the other way around.” pii'And how much sense does that make?” Morgan snarled. “He’s supposed to be working with us. This is a mess.”

Jo cleared her throat. “What are you going to tell the President?’ ’

Don’t even ask.” He studied her for a moment, running through the events in his mind. She was watching him. She looked wary, afraid he was going to demote her, most likely. He just might. SAFE hadn’t been around very long, but they’d accomplished the few missions they’d had so far. They couldn’t afford this kind of screwup this early in their operational life. “I think Gamma Team needs an overhaul.”

Jo shriveled a bit. “I understand,” she said. “I can move to—”

“Not you,” he said. “I want your peopie to go over everything we know and go over it again. Learn to use those weapons. Friend or foe, the Hulk should have been stopped. ’

“With all due respect, sir, that’s a tall order.’’

He nodded. After a moment he said, “What happened with the call, Jo?”

“The call?”

“Banner called you,” Morgan said. ‘And Tom said half the world heard the conversation. Tell me about that.”

She shrugged. “I received a phone call from Dr. Banner. He made a reference to Senator Hill’s plane and then clicked off.”

“Clicked off.” He glared at her.

“Yes, sir.”

‘And you perceived that as a direat?” He stood up,

came around beside her in a fluid motion, hovering over her shoulder.

“Sir,” she said, “if you get a call from a one-ton gamma-augmented creature who’s a known security threat and he tells you to go tcf the airport because a plane is about to have trouble, you go.”

' He folded his arms. “All right. But what about the media, monitoring the call?”

She looked at him, her dark eyes searching for an answer that would satisfy him. ‘-:A security breach of enormous proportions.”

He rubbed his. eyes and breathed into his hands. He felt as bad as he was sure he looked. “I want the communications system gone over with a fine-tooth comb. I want every log-in checked. Someone’s taking us for a ride, and I want that ride to end. Now.”

“I was thinking the same thing, she said.

The screen behind the desk crackled and Morgan turned around. I fizzed white for a few moments before coming alive. There, over the desk, in a nice mahogany frame where Morgan alternated a series of favorite works of art, was the face of the President of the United States. And the saints come marching in. “Mr. President.” “Sean.” The man in the screen was sitting behind his desk. He was wearing a polo shirt and appeared just this side of livid. “So we’re working with assassins, now, is that it?”

I don’t have a confirm on that yet, sir.”

“Looks pretty confirmed on the ten o’clock news,” said the President, scowling. “Do I need to remind you that SAFE is still a fairly unwelcome pet project in some circles? Your budget is as expendable as it is limited, and this Hulk thing ..The man paused, swiping his hand across his desk. “This really looks bad. ’

“Mr. President,” said Sean, “I’m not sure he did it.” “Come again?” The chief executive officer looked

bewildered, “I’ve seen the films myself. He jumped up there and—”

“And it blew up.” Morgan closed his eyes. “And I myself have been aware of similar public occurrences that were complete ruses. ’ Planned a few, too.

['■‘Yeah, I’ll bet.” .

“Sir—”

“I want the Hulk and SAFE as far apart as possible.” Morgan was ready for that. Jo had her arms folded, head straight, but she was watching Morgan as if she had been personally wounded. “We need him for this one,”

‘ ‘The Abomination thing?’ ’

“Yes, sir, the Abomination thing.” Blonsky is slaughtering people and the President calls it a “thing.’’ Everything always came down to perspective.

“I just got off the horn with S.H.I.E.L.D., and they think—”

• “This is a SAFE operation, sir. Domestic. It’s off S.H.LE.L.D.’s turf.”

The President went on as if Morgan hadn’t spoken. “They don’t trust the Hulk, for obvious reasons.”

“Sir, the public hardly knows SAFE exists.”

“And this is a terrible way to introduce yourselves.” “I think something big is happening. And I think the Hulk is important to us in solving it. He tore through us like papier-mache, sir. The Abomination can do the same. But I think Banner is still on our side, the same way he was during that mess with Spiaer-Man, Hydra, and A.I.M., and I want his help.” .

The President nodded, but not in agreement. “Sean, the public perception at this hour is that the Hulk just killed a national figure for no reason.”

“And I think it’s wrong. ’

“And I’m telling you,” said the man behind the desk, “that on my side of the fence perception is not just reality, it’s everything.”

Morgan looked at Jo. Amazing. All those stiletto-wielding years and his true talents were being tested in a game of politics. ‘Mr. President.” Morgan waited a second. “The Abomination is our main concern right now. I’ve got weird things happening and the Abomination doing increasingly dangerous things. I think, somehow, he may have been involved in the assassination. And if I need the Hulk—’ ’

“Use him,’ the President interrupted.

“Sorry?"

“I said use him. But it’s your head.” The man looked down at his desk and looked at his watch. He reached toward an intercom and said, ‘This conversation never happened.”

The screen blinked off abruptly. Morgan shook his head.

He turned to Jo, stabbing at her with a finger. “Let’s get on the ball,” said Morgan. "“I want all systems go.'!

“He’s completely insane,’ Betty said. She ran a towel through Bruce’s hair, and he leaned his head back against her chest as she did so. Bruce’s study was dark, lit only by the constant glow from the screen. Betty brought the white towel away and inspected it. “Finally,” she said. “I think the third wash finally got all the gunk out.”

“Sorry,” he mumbled. He scratched his chin and jerked his head sideways while she knuckled at his ear with the towel. Bruce sat facing the computer, like Betty, still dripping wet, wearing only a towel. (Actually, it was a terrydoth blanket, formerly a robe. Life with the Banners was a constant juryrig.)

Betty had been shocked when Bruce had finally made it home in the dead of night. She had seen him on television, the death of the senator so near. Some reports said that he appealed to meet with or pursue another greenskinned creature off the field. She saw the film of her husband emerging from the rubble of the building, the front falling and spewing dense clouds of particles and building materials and glass. And there was Bruce, up from the rubble, his arms wrapped as if in prayer around a child so small he nestled in the groove between Bruce’s iirms. She saw the people back away. She saw her husband set the child down as the people flinched back, and he flinched himself. And then the police started to move and Bruce leapt. Two hours later he was home.

“I saw a mention on the eleven o’clock report about the kid in the cave-in,” Betty said helpfully. He just looked up at her. It was not enough. The plane was bigger news, the strange incident with the collapsing building more like an aberration, hard to reconcile with conventional wisdom and thus bound to be publicly ignored. “I guess we’re lucky we haven’t been raided yet, huh?”

He nodded, looking back at the computer. “I think so,” he said. He looked at her again. “I think we have a guardian angel. Someone is protecting us.” -./'‘Morgan?” Betty asked. When Bruce nodded she said, “Then I guess we gotta catch Emil, huh? Earn our keep.?'-’

The Hulk nodded, taking her by the arm, gently and bringing her around before him. Bruce scrolled down the Proverb as Betty climbed into place on Bruce’s massive right leg, nestled against his torso. “That’s true,” he said. “But more than that, you’re right. Emil is completely insane.” Bruce studied her eyes, then the verse. “He’s just so—so disparate. At one minute he’s sitting in the dark reciting poetry, then he’s blowing up planes by remote control. He’ll be sensitive and even seem almost—” Bruce struggled for a word “—sorrowful, and then he’s throwing columns at me, deliberately endangering the lives of the people in the area.”

“Is this still revenge?” Betty asked.

“I’m not sure,” Bruce mused. “Morgan suggested that maybe Emil is working with someone, someone who could provide him with technology to get a few of his own grudges out of the way. But what next?’ ’

Betty leaned back against him, folding her arms over her chest, above the edge of her towel. The fold slipped and she busied herself loosely refolding it. “So where are we on the list?”

:= E‘He made some progress,” said Bruce. “Eyes, hands, heart, and feet are down. ’

■■All the body parts,” she mused. “Hm. Except the lying tongue.”'r,

“That’s different, though. That’s interior, the others are all extremities. He took care of extremities first. Personal,” Bruce whispered. “Personal! Body parts!” -“I think I understand,” she said, “but go ahead and enlighten me anyway.”

“I think Emil’s played all the personal cards,’ said Bruce. ‘ And if this is the formula he’s working from, then it’s possible the next moves might not involve him personally at all. Whatever his deal is, it might fit into the next dominoes to fall.”

“Maybe not, though,” said Betty. “Too early to say. He got another one, too. The false witness that uttereth (ies. He created that ‘Abomination’ himself.”

“By setting me up,’ Bruce sighed angrily. “Concentrate on what it means, hon,’ she said. “It means he’s not above making an Abomination if there’s not one around to punish.”

“Maybe,” he said. ‘Or maybe the press was already an Abomination and he just gave them a part to play. And he punished me, not them.”

“So what’s left?”

“Only two. The tongue—”

‘ ‘And the person, ’ she said. The last Abomination is a whole person: ‘He that soweth discord among brethren.’ ”

“God, I wish he’d be consistent,” Bruce sighed. “We can’t know if that’s a sower of discord he’ll punish, or if—”

“Or if Emil will be the sower of discord himself. But

remember what he said. ‘I will be what I am. ”

“And what he is, is an Abomination.” Bruce pulled her back against him, gently, and whispered into her hair. ‘“And what / am is a fool. That’s what he’s helping me

see.”

“No.”

“Yes.” he whispered. “Emil has played me like a violin. You can’t deny that.’-H ‘:‘You do what you have to,” she said, turning around slightly in his lap to look in his eyes, the towels sliding around on damp skin. “Bruce, listen: you’re doing the best you can with Emil. He lures you into situations and he ties your hands behind your back because he knows. He knows that the biggest difference between you two is that he doesn’t care who gets hurt. Emil has divorced himself from the whole world, he may not even consider himself human anymore.”

Bruce turned his head away, looking at the black curtains, the giant green jaw clenched. “And what should I consider myself?”

“You,” she said, turning his chin back and kissing it, fc'are Bruce. A giant green Bruce, but a human Bruce nevertheless.”

“I know,’ he nodded, “I know But there are times when I’m down there underground and Emil is waiting in the darkness and I realize something. Something frightening.”

“What?”

“The savage Hulk would never get in these situations. In the back of my head there’s a creature that wants to lash out, that doesn’t follow clues and has no interesi. in science, that would know exactly how to stop this monster. Exactly how. And the horrible truth is, it’s not by stopping to hold roofs up.” He looked into her eyes. “Do you understand? That’s the fool he’s shown me to be— or that he’s trying to show me. That I’m the only one who can stop him and I won’t because I’m a fool, because—

because I refuse to be shown what I really am.”

Betty trembled a bit. ‘And what is that?”

“A savage,” he said. '‘A beast. An avenger for him.” Betty’s mind filled with images from years of her life she tried to forget. All those years that Bruce had no control, when he lashed out in rage and anger and had no desire to control his strength. And deep inside she knew that she had been in danger so many times, that it was only the last vestiges of the humaa within the savage Hulk that had recognized her, time and time again, when he could just as easily have exploded, have taken her and squashed her like a bug.

^ “But that’s not what you are,” she said, sitting up a litde, clamping her fingers around his giant jaw, looking Bruce in the eye. “Even when you were the savage Hulk you were never.... Bruce, you never hurt me. And you could have. I’ve seen violent men. And you had physical, brute strength like no one had ever seen, the same strength you now have. But even then, there was something good in you.”

“But I did hurt people,’^he said, far away.

“You just—’ she started, closing her eyes, breathing on his cheek. She could play the stories he had told her in her head like home movies: Bruce’s father the monster, the tyrant, the destroyer: Bruce the child, the victim, the anger boiling inside him and finally unleashed, after all those years of control, in one blinding flash in the sandy desert. She thought about that child, the fists pounding into tiny shoulder blades and ears, the screams of hatred from the father, and she reached out in her mind, grasping at the image. So much could have been avoided. “You just wanted to be left alone. I know there are demons inside you, Bruce. I know you sit in the dark and brood because you worry that you’re going to lose control. But I know in my very bones that you won’t.”

‘‘How?” the Hulk whispered.

"Because you beat those demons, day after day. And

I know that if they were held in check while you really were the savage, then you will always hold them in check now that you aren’t.”

“Betty,” the Hulk said, half smiling, his giant hands wrapped around either side of her slender waist. “How did you ever get to have so much faith in me?”

She bent forward, wrapping her arms around his neck, the towel falling away. “You have to ask?”

Sarah Josef of URSA, late of the KGB, walked quickly up the stairs to her Greenwich Village apartment. The exercise did her good, legs pumping steadily up the ten flights, her breath barely registering the exertion. Besides, it fit the part she played here, that of an art student at CUNY with a penchant for the hardbody thing. The doorman and she exchanged pleasantries, but he would be one of the few people who would see her—taking the stairs rather than the elevator kept her from spending too much time in small rooms with strangers who might want to talk with an attractive young student, might memorize too many features. Soon, she would be gone.

Sarah reached her door and silently extracted her key as she ran a finger softly down the edge of the door. Her fingertip brushed the tiny hair she had deftly wedged between the door and the frame—a ridiculously outdated trick, but generally effective. She twisted her lip, reasonably satisfied, then placed the key in the lock, turned it, and let the door fall open with a slight shove. The hair fell, black and ghostly, disappearing into the old carpet.

The URSA operative stepped into the entry hall. The television was still playing as she had left it, displaying one of a thousand talk shows that infested American daytime television, she was given to understand, since the programmers had discovered that such nonsense was far cheaper than reruns of old programs. In fact, she was somewhat nostalgic about that, she observed as she set her handbag down on the table in the drab kitchenette.

Sarah had been raised most of her life in what she had been told was a perfect model of an American town, save its placement in the outskirts of Moscow. Television was a major part of their training—she had to learn how Americans watched it, deferred to it, prayed to it.

In fact, Sarah was speaking English with her fellow trainees, her “cousins,” and watching The Andy Griffith Show when she had been called out of the living room, all those years ago. Told her father had been killed by an American operative. Told to mourn.

Sarah stared at the table and saw her reflection in the glass tabletop, haloed by a chintzy chandelier behind her head, in what was optimistically referred to as a den. The chandelier was a tasteless ode to extravagance such as might be found throughout the United States, from its ugly glass clumps and bulbs to the ugly rusted gold base from which it hung.

Her eyes travelled back to her own reflection. She had received the news of her father’s death with a dull, aching tranquility. She had wandered back to the living room and sat down beside her cousins, the ache ripping through her, tearing apart every cell and rebuilding it as she stared intently at the pixellated images of Andy and Barney. At the feet of the laughing pair lay the body of her father, a big man who loved her and provided for her and served his country honestly and loyally. Who held her on his knee every third Wednesday when she could have visitors, who was proud of her intelligence and her placement in the home of the cousins.

She had wished she were out on the obstacle course, tearing the throat out of a dummy with a straight razor, but one had a schedule, and there she sat, the razor in her mind only, her eyes on Andy. And Andy didn’t trust Barney and he only let him have one bullet, ha ha. And there was a man out there like Andy who had met her father on a foot bridge and shot him to death and disappeared. She watched the American lawman on television, sitting on the porch vyith a freckle-faced boy eating the pie offered by the corpulent aunt he kept as a servant. And in his pleasant smiles and laughs she saw a bum of evil and a sound of malevolence, in her dreams the sheriff patted Opie on the head and walked down the street with his gun to the footbridge and shot her father. For years, as Sarah trained, fists pounding into straw men and razors slicing through latex necks and real necks alike, every face was Andy.

Until one day, at the same time the Berlin Wall was falling and the cousins were seeing less and less of one another and some were wondering if there could ever be a place for them, Sarah was given a dossier that finally busted Andy’s face, sent the shards of apple-pie warmth and Aunt-Bea slavery spinning into the abyss. And as Mayberry shattered into shards of glass and apple pie, Sean Morgan’s face settled onto the wiry frame of the sheriff. And that was the day she grew up.

Sarah stared into the glass tabletop at the reflection of her own head and the ridiculous chandelier halo, the shards clumping back together here, in New York, where it would finally happen. She saw Sean Morgan, her razor finding its mark, blood flying like liquid shards, and she thought she saw the blood blend into the spots of rust on the gold-painted metal base of the chandelier, the whole mess reflected in the tabletop, the room warped and reflected in the gold, a reflection in a reflection. There was a shape on the couch. She heard a metallic creak.

There was a shape in the gold base. A reflection— someone on the couch, how did I not see—

Sarah spun around, dropping, gun appearing from her sleeve. Then she sighed.

F.mil Blonsky, in all his scaly glory, sat still, one long, clawed hand stretched over the back of the couch, mouth curled in what might have been, save for the monstrous gamma disfigurement, a smile. “Sarah.”

Sarah bolstered her sidearm and brightened. “You slipped through my defenses, Uncle.”

hair across the window sill? You read too many Fleming novels,” said Emil. “I trust using your apartment is acceptable.”

She nodded. “Absolutely. Your underground lair is being crawled over by SAFE agents far too often for you to stay there. And you needn’t worry, you won’t be found here.’’

“What about the satellite?”

“The GammaTrac?” Sarah cocked an eyebrow and smiled. “Our person on the inside has taken care of that. The Abomination has been quietly and reliably deselected. You won’t even show up onscreen.”

“Not until I am there,” said Emil.

■. “Until we are both there,” Sarah replied. She looked at his claw where it lay on the couch and saw that Emil held a small box, wrapped in gold paper. Sarah went to the couch and sat next to Emil. He was hideous, it was true. And dangerous. But somewhere in there was the man she had called uncle, who came to visit with her father, all those years ago, before Father’s death and Emil’s disappearance. Emil had not recognized her when she had first come to visit, but she had certainly recognized him, the tall, strong man underneath, the one who sniffed the air and could find the chewing gum hidden in the secret compartment underneath her desk. Who could do magic. Utterly different, but there underneath the scaly skin of this Abominable thing. She sat on the couch looking at the Abomination and seeing Uncle, and indicated the package. “What’s this?’*

‘Ah,” said Emil. He lifted the small box. “Today is the. eighth of March, of course,” .

She shook her head. “The eighth of March?”

The red eyes glimmered. “You know nothing of this— International Women’s Day?’j*=j

Her cheeks flushed. “The truth is, Uncle, the cousins

didn’t observe the holidays everyone else did.”

“Hm,” Emil said, looking at the floor. “It is a pity you missed them. When I was a child we lived for the state holidays—all of them in celebration of the citizens and the people. Well.” He handed the package to her, and she took it in both hands. “International Women’s Day is the day when all the boys bring small gifts for the girls with whom they share desks in school.”

Underneath the gold paper was a thin cardboard box, and this she opened. Poking though a layer of styrofoam packing kernels she saw a porcelain head, painted yellow. Sarah extracted the statuette and set it on the coffee table. “Who is it?”

“Why,” said Emil, “this is Princess Vasilissa and the Horse of Power.”

Sitting on a small black base was a mound of porcelain painted to resemble a grassy field. Standing upon the mound were two figures—one a golden-haired woman, undoubtedly a princess by the crown and robe. Next to her was a horse, gray and strong, nuzzling the princess’s cheek. “The Horse of Power.”

“Do you know the tale?”

She felt embarrassed again. Her childhood was filled with training and reruns. “No, Uncle.”

“The Horse of Power was a magical creature, wise and powerful. He led his master the archer to the Princess Vasilissa. Vasilissa won the kingdom for the archer, and helped vanquish the evil Tzar. Even the fairy tale said that there were no such horses today—but that they sleep.” Sarah stared at the figures, running a slender hand along the back of the horse. She looked back at Emil. “They sleep?”

“The horses of old sleep underground with the bo-gatirs who rode them,’ ' Emil rasped, red eyes sparkling. “And someday the horn will sound, and the bogatirs will rise with the horses of power, the snow will crack and steam and the hooves will break through, and the bogatirs and the horses of power will reclaim the land, and vanquish the foes of God and the Tzar.” Emil looked at her, eyes narrowing, and Sarah held her breath. His voice was hypnotic, when he wanted it to be, when he cared about the subject. “That is the legend, anyway.”

She shook her head. ‘Thank you.”

“It is a small thing, a child’s gift,” Emil chuckled. “It saddens me that you know so little of the culture. Especially when you work for an organization that holds the restoration of Soviet culture as one of its primary goals.”

“My reasons for belonging to, for working for URSA, are my own,” she said.

“And do all of them center on revenge for the death of your father?” Emil asked.

“My father believed in something that Russia does not. He served the Soviet Union. I was raised for that same purpose,” she said. “The country doesn’t even know itself anymore.”

“That may be,” Emil scratched his scaled chin. “But the country you knew, the Soviet Union I knew as a child, were far different from the Russia of Nicky and Alexandra’s Russia^ Identities of states change, I may be terribly romantic about the past, but all states evolve.”

“Do you think the move away from Communism was an evolution?”

He sighed. “I don’t know. Sometimes I think perhaps the move away from old-fashioned feudalism was a mistake. But it’s hard to be fair. I miss the Soviet Union because I knew it as a child. Do I think about bread lines? No. Wretched food? No. I think about Sputnik and parades and public performances of Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky. I miss the pseudohistory that tied Kruschev’s Russia to the Horse of Power. So many falsehoods and truths, and what do I miss most? International Women’s Day.” Sarah looked down at the statuette and somehow saw

Andy Griffith shooting it to smithereens. “Tell me about my father.”

“Karl Josef,” Emil rtodded. “Karl was a good man, and I mean that sincerely. I met Karl in grade school. He was an excellent marksman, and when he was twelve your grandfather gave him a competition-style rifle, a beautiful piece. I remember he used it forever. There was a time in Istanbul when I wasn’t sure he was alive, and we had another Ihree days before our intended next meeting. I was afraid I’d have to go home without him, tell your mother the awful news. And I heard that rifle of his, across the city, while I sat in a cafe. It was a good rifle—distinctive.”

“Yes,” she said. “I know.”

“Ah. Of course.” He sighed. “As it happened, your mother passed on before Karl did. And I was not the one to break the news to you, because I was sent almost immediately to the United States again. By that time I dare say I would not have recognized you anyway. Those were heady times. I don’t think Karl and I had had the chance to see you for five years. When you showed up underground, I had almost forgotten that there was a Sarah Josef.”

“You’re a hero, Uncle, do you know that?”

“A hero, ’ Emil replied, setting the glass down.

‘They have a fine way of showing it/’

“What do you mean?”

‘Sarah, the government you are trying to revive hung me out to dry the moment I became this,” Emil spat, holding out his claws. “They wanted nothing more to do with me. All lines were closed. I couldn’t even get in touch with my wife. Would you believe they told Nadia I was deadT ’

ft “I know,” Sarah said. “But there are those who talk about you, Emil. Who know that there was an operative called Blonsky who came to the U.S. and fought their champion—however a misunderstanding that might be— the Hulk, and was turned into a monster. URSA knows about that. You’re a model of dedication. It’s not the foul bureaucrats who betrayed you that URSA wants to restore to power. They want to give it a better try, to do Communism right. No backstabbing, no interdepartmental intrigue. You are a model for that kind of dedication.” She heard nerseif talking and saw him watching her and she stopped. She sounded like a fool, but she continued. “Our plan is the perfect end to the standing government. So much will be accomplished when the Russian Embassy is destroyed by the United States government before the eyes of the nation. The Cold War will be dug up and reheated within hours. The new government at home will be in place, guaranteed, by the time you get there, Uncle. And I’m sure you can find a pi—”

“No,” Emil said. “When this is over, do what you will. The Abomination will be no more. You can make the world over in whatever image you like. I have my own plans.”

“And I mine, ’ said_ Sarah. “And they start with the death of Sean Morgan.”

“Oh, yes,’; said Emil, and he smiled. ‘No safety net for him, I’m afraid.”

“I’m very pleased that she agreed to see me.” Betty walked with her hands on hei handbag, pressed against her belly, as if in supplication. They were walking along a brightly lit hallway that shone of gold and marble. At the end of the hall was a large, glass, double-door, exit which looked out onto a sun deck and a lovely garden, perfect for entertaining. As daughter to General Thaddeus “Thunderbolt” Ross she had spent time in consulates before, at Christmas parties and the like. As a girl, places like this had made her nervous—all the crystal and china, the prefect rugs. As an adult, she felt the paranoia coming back, the sense that at any moment she would stumble and knock something priceless onto the floor and into a thousand pieces.

“She didn’t agree, came a voice. A tall, athletic-looking man in a dark suit appeared from an office and joined Betty and Krupke.

he hasn’t taken a lot of visitors,” said the ambassador’s assistant, whose name was Krupke.

Betty looked up The man was perfectly framed by the office door behind him, a large rectangle of dark wood behind a perfectly triangular torso. “I’m sorry?”

“Greg Vranjesevic,” the man said, extending a firm hand, which Betty grasped and shook.

“Oh! Mr. Ambassador,” she said. “I’m Betty Gay-nor, Richards College.”

“I know,” he said, smiling. He had a disarming smile. Betty bit her lip. “Should I call you Mr. Vran— ’ “Vranjesevic?” He grinned, saying the name quickly. Betty processed the sound for about the fortieth time and still couldn’t decide if it sounded like Fran-chez-eh-vick or Vrahn-yez-eeh-veesh. Greg saw her trying to mouth it and said, “The problem is that you’re trying to imagine

it written in Arabic letters. Call me Greg, everyone does.” “Thank you,” she said, staring at the tall man. “You said that Nadia didn’t want to see me?”

“It’s not that,” said Greg. His English was almost perfect, with the slightest accent, a hint of Bela Lugosi to drive the locals wild. “It’s just that she hasn’t much felt like seeing anyone since the incident at the Langley. But I thought perhaps it’s time she came out of her shell a little bit.”

Betty nodded. Bruce had wanted to talk to Nadia Dor-nova, to see what else might be learned from her. And since Bruce was big, green, and a fugitive, Betty was the only choice for the job.

Betty nodded. “She’s something of an idol of mine,” she lied cheerfully. “And my class has been studying Antigone, and the relation of religion and piety to the state. I thought perhaps I could talk to her. But perhaps—” “That’s fine,” said Greg, nodding equally cheerfully. He seemed to come just short of winking at her. Betty looked past him into Greg’s office. There was a man by the window muttering into a cellular phone, in an equally severe suit. She heard a Midwestern accent and saw the man look away from the lovely curtains and throw her a glance, nodding. A SAFE agent.

Greg tapped her on the arm and led her down the hall to the door onto the deck. “At any rate,” he said, “if she won’t come out of her shell—perhaps you should go in?” Betty opened the door and stepped onto the deck which buttressed the garden and heard the door click shut behind her.

Greg eiuered his office again and said, “Who is she?” Julius Timm clicked his phone shut and stuck it in his pocket. He shrugged. “Upstairs said let her in. She’s safe, that’s all I can say.”

‘ ‘Really? Safe or SAFE?” Greg frowned, sitting at his desk. “That’s all you can say? I have an American agent in my office and another one waltzing down the hall and even the KGB tells me to be nice to her, and even they aren’t sure why.^jH

“Cooperation,M. smiled Timm, “is a wonderful tiling.”

“All I can say,” Greg mused, putting his hands behind his head, “is that I hate being out of the loop. So the KGB is cooperating with SAFE, is it? And Nadia knows something?”

Timm shrugged.'‘'Can’t hurt to have a visitor.”

..-;£‘Is she really a professor?” he said.

^“Oh, yes.”

Greg frowned again. “Fine. But remember—you assured me that this woman had been checked out by both governments, and that at the very least she’s not an assassin.”

“She’s not an assassin.”

“So who is she?”

“Betty Gaynor.”

Greg resisted an urge to pummel Timm into the ground. “Who is she really?’j™

“A very helpful angle, hopefully.”

Sunlight dappled the garden and lit the water in the fountain. Betty looked around her, stepping out on the stone deck. Here and there statues danced and played instruments, moss grew out of stone navels and mouths. Betty held up a hand to shield her eyes and looked back, to the stone wall on the other end of the garden. Ivy covered the wall, and she caught the blue glint of a peacock wandering by. Then she sav- rhe garden chair and the blonde woman on it. She wore a silk kimono, a cup of coffee by her side.

“Ms. Domova?’ Betty stepped off the deck and onto the beautifully manicured lawn. Nadia was staring at the peacock and looked up.

“Yes?” Nadia frowned, but it was an almost sweet frown, as if she didn’t want to be rude.

“Hello, I’m terribly sorry to bother you.”

“Are you a reporter?” Nadia threw a quick glance up and down Betty’s blazer and skirt.

“No, I’m a teacher.”

Nadia sat up a bit as Betty stood by another lawn chair, fingering the iron lip of the chair back. “What can I do for you, Ms.-—?”

“Gaynor,” Betty said. ‘Betty Gaynor.” She held out a hand and Nadia took it. Her grasp was timid, as if she were floating and afraid to touch anything lest she gain weight and fall. Nadia had been here, at the consulate, ever since the incident at the Langley. She was not giving interviews. The show did not go on. Betty continued, “I read about what happened, what happened to you—’ ’ “Not to me,” Nadia shook her head. “Everyone but me.”

“If I may,” said Betty, gently “everyone and you. You were the target. He did this to hurt you. And it worked.”

■ “Ah, you’re a psychiatrist.”

“No,” Betty said, smiling. “I was almost a nun, once. And I’ve been a counselor, but, as the saying goes, I’m not a licensed therapist.”

“I don’t know why that comforts me.”

“I teach a religion class at Richards College. Ostensibly I’m here to ask you your thoughts about Antigone. Since you play her every night, perhaps you had some insight.”

Nadia leaned forward and picked up her glass of tea. She lowered her sunglasses, smiling. “Please,” she said, “sit down. I can’t believe how rude I can be. Would you like some iced tea?”

Betty thought about that as she sat down on the ornate iron lawn chair. “Iced tea? Where does a Russian girl develop an affinity for iced tea?”"

“On tour in Texas, that’s where,1’ laughed Nadia. “I know what you mean, though.” Nadia pushed a buzzer on the small table and shortly thereafter, a servant appeared in the garden. Nadia spoke a quick Russian word and the servant disappeared again.

Nadia leaned back. “Ostensibly.”

“Hm?” Betty’s tea appeared and she thanked the waiter graciously as he dissolved through the stone and moss and back into the consulate.

“You said that Antigone was what you were here about, ‘ostensibly.’.'-

Betty smiled. “Very good. Very good.” She sipped her tea.

“I don’t know why I feel like talking to you, Ms. Gaynor. Perhaps it’s your disdain for a straight answer. Or maybe it’s just the hint of fallen nun about you.” “Betty,” the fallen nun said. “Call me Betty.1’

“Not easy to get into the consulate. They let me in because I’m the ambassador’s girlfriend.”

Betty looked at the peacock. “Do you ever want to go home, Ms. Domova?”

“Nadia. Sometimes.”

“Why don’t you?” Betty asked, and then she felt the harshness of the question.

Nadia didn’t seem to consider it harsh, or ignored that. “Things change. People are gone. It’s a cliche to say you can’t go home, out it’s not any less true.”

Betty shifted her weight and sipped her iced tea. ‘You were married once.: ’

‘‘Yes,” Nadia nodded, “For about six yearsfi^^ “What was his name?”

‘Emil,” she said. “Emil Blonsky. My—what’s that other cliche?—my high school sweetheart? We shared desks when we were young.”

“Really?” Betty .aughed. She wasn’t sure why that was funny, except that she was trying to picture the Abomination behind a child’s desk. The moment she caught the image the green monster shrank in her mind, and all the lost mass became a wave of sadness fhat washed over her and killed the laughter.

“Yes,’" Nadia said. “And on March 8th, Women’s Day, at the end of our last class together, he gave me an engagement ring.” Nadia rested her chin on her palm, a dainty pose, elbow on the arm or her chair. “He was going in the Army, he said, and had bought the ring with his savings. Hard to save money, then.”

“Is that what your husband did?”