NEW YORK

BOULEVARD BOOKS, NEW YORK

If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

Special thanks to Ginjer Buchanan, Steve Roman, stacy Gittelman, Mike Thomas, Steve Belding John Conroy, Brad Foltz, and Carol D. Page.

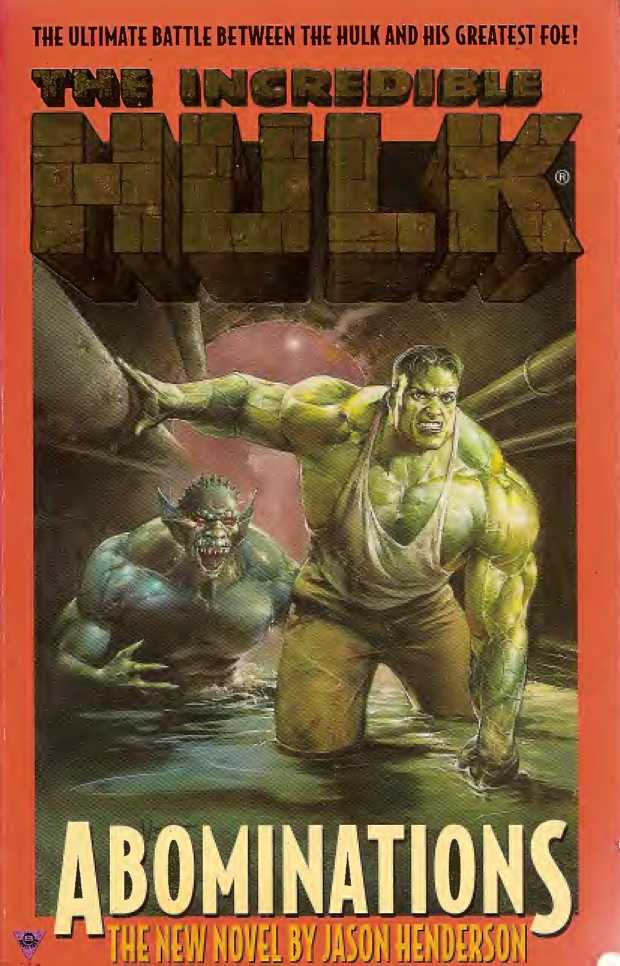

THE INCREDIBLE HULK: ABOMINATIONS

A Boulevard Book A Byron Preiss Multimedia Company, Inc. Book

PRINTING HISTORY Boulevard paperback edition July 1997

All rights reserved.

Copyright Q 199? Marvel Characters, Inc.

Edited by Keith R.A. DeCandido.

Cover design by Claude Goodwin.

Cover art by Vince Evans.

Interior design by Michael Mendelsohn.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: Byron Preiss Multimedia Company, Inc.,

24 West 25th Street, New York, New York 10010.

ISBN 1-57297-273-4

BOULEVARD

Boulevard Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016. BOULEVARD and its logo are trademarks belonging to Berkley Publishing Corporation.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 987 654321

—For Earnest Bell, my Hero and my Grandpa.

For heip with Russian customs and holidays, my thanks go out to Marina Frants, who was dratted to the cause by virtue of her marriage to Keith R.A. DeCanaido, my editor, and who at least kept me from making a complete fool of myself. Whatever I still managed to get wrong is my own fault, of course. Thanks to Keith for his help and patience and more thanks for all the comics to get me up to speed.

Thanks to Pierre Askegren for co-creating Sean Morgan and letting me put him through hell.

Oh, and for inspiration, thanks to Toy Biz for the really cool Doctor Banner and Abomination figures. My wife is sick of me making fighting noises and throwing them around the home office, but I call it work.

There is grief.

Thank God there are heroes.

CHAfTilR 1

Sometimes I wake up and time is moving backward.

It is just after the gamma blast. I am on my back, writhing, pinned to a sheet of green glass the size of a skating rink that a few moments before was hot New Mexico sand. My hand is still in front of my face, and I can see the bones underneath my flesh glowing green and fiery. The gamma wave is flying fast and backward, though, backward with time. Now the sudden-born rage snuffs out again; time is flying past the moment’s birth.

Backward screams fly into my mouth and strips of clothing slap across my body as I fly off the green glass that turns brown and grainy. My feet go back into my shoes and hit the sand and my hand is still infront of my eyes as the wave rips past me and back to the opening flash.

Time careens backward and the flash is visible through my hand but now my hand is dropping. I see the beginning of the flash shrink down into the sand of the horizon, the gamma heat soaring back with the flash and leaving me standing in the New Mexico sand, beautifid, clouds moving backward.

Sometimes I wake up and it is before the gamma flash.

I am a man, my flesh is pink and always will be, my body is weak and always will be, my rage is human and_ controlled, like everyone else's. Eveiyone.

Sometimes I wake up and time moves backward and I am not tall, or angry, or strong, except in the ways I know and have seen a million times. My rage is safely hidden, it trudges through my mind unknown and unobtrusive. Sometimes I wake up and it is before the gamma flash and my life is small and I love it and hate it and am a normal man.

Sometimes I wake - up and lime moves backward and I am not green.

Damage foilowed the Hulk. The Hulk walked on the concrete road and killed it slowly, even as gingerly as he stepped. Despite his efforts, the concrete cracked, in tiny, inscrutable cracks taking years off the life of the thoroughfare. Step out at night, try to do some thinking, and what happens? Damage.

The Hulk walked the roads at m^ht wondering why he was being watched when he heard the sound. Just after he heard the sound of the crash, that godawful wailing metal sound, the Hulk reached the top of a hill and looked down bn a highway of licking f!ames™scattering and worming through bubbling jelly and cracked glass, cooling into a frozen purple lake of fire.

But that was after.

Fact #1. The freeways are built for trucks. There is no secret about this. Save for some heavily travelled parts of densely populated towns, the freeway system that laces through North America is chiefly a thoroughfare for the tractor-irailer. Certainly, cars are allowed. In the daytime, the trucks share the roads and let everybody else drive, too, but none of them are happy about it. At night, the trucks rule the roads.

Fact #2. Songs about car wrecks jangle arid careen across the airwaves like debris. There are a lot of them, and most o: them are awful n varieties of awful that changc with the decades, from the sublimely morbid “Warm Leatherette of the 1980s back to the mercilessly smarmy *sen AngeF of the 1950s. Car wrecks are the stuff of songs that people really like to sing and dance to. No one can say exactly why.

Fact #3. The car radio plays the same songs as the radio at home.

There is an interchange just north"6f W1 ire Plains, New York, where Route 4, moving westward, swoops up and around to meet Interstate 365, and the exit from 1-365 does the same in the opposite direction to get onto Route 4. Opposing vehicles pass one another on the curving ramp at the legal maximum speed of forty miles per hour. At forty, tons of metal careening into each other are already lethal, but forty is merely a bon geste on the part of the state of New York. Most cars make the interchange at fifty-five or sixty, sailing past their counterparts, usually separated by about ten feet of air and the perceived safety net of a sheet metal guardrail and, almost jokingly, a mesh of chain-link fcncing.

At eleven p.m. on February 20th, Alex Deere travelled north on 1-365 and prepared to exit onto Route 4. Deere drove an eighteen-wheel tractor-trailer, the kind that, as noted, rule the road. To say that he was preparing to make the interchange is not entirely correct. He was falling asleep, and looldng for the interchange whenever he managed to wake up. Alex blinked and tried to focus on the oad, thudded awake by the turtlelike bumps built for exactly that purpose. His eyes travelled from his knuckles on the steering wheel to the trip report suction-cupped to the dashboard. He shook his head. He had been driving for eighteen hours.

Alex took a deep breath and rolled down the window, allowing the slicing cold air to fly in. He blinked. The hell with them. The hell with them and their Jumbo’s Jelly and their deadlines. The hell with their pressure and their “Welcome to the Jumbo’s Jelly family!” speechesZl don’t need this. (“Sorry, no, we need it by Thursday.”)

Deere grabbed Ms radio and keyed the mike. “Breaker one-nine,” he mumbled. “This is Jumbo Dog. Breaker one-nine for a radio checks He took off his cap and let tne air blow his hair around. Sleep rumbled like a distant wave in the background, an animal frightened away from camp for a moment, but still there, lurking. Deere watched the road fly underneath his hood and thanked God the roads were clear. Three days, ago this route was covered in snow. Now the ice and snow had been pushed onto the side of the road so the trucks could get through, so people everywhere could get their peanuts and popcorn and Jumbo’s Jelly.

The radio crackled. A voice popped out of the night and rasped through the wires.ft'Loud raid clear, Jumbo Dogjg came the answer. “This is Backpack. What's your twenty?”

Deere looked out. God. Someone to talk to. Even for a second. The animal sleep growled and slunk back a, bit more. “Three-sixty-five North. Backpack. About three miles to Route 4.”

“Hell,” came the response. “We’re neighbors. I’m on 3^5 too, passed 4 a while back, mus. have passed you just a few minutes ago.”

Welcome, said Alex. The disembodied voice was moving in the opposite direction. For a moment Deere considered that he and the party on the other end had been about twenty feet from one another a few minutes ago, [ravelling in opposite directions. It didn’t mean much, but just struck him funny.

‘Right,” said the radio. “You sound beat, Jumbo. Whassamatter, you been- eatin’ too much o’ that jelly? Need a nap?”

Deere laughed. “Hell. Just a little tired. S Then he yawned, despite himself, as he keyed off the mike.

Backpack came back. “How long ya been out, Jumbo

Dog?” _

“Light—iii^hiaen hours.”

There was a pause, and Deere watched the road, which had gotten shiny. A few wet specks struck the windshield and he grimaced. It was starting to rain. After a few sec-

onds Backpack came on again and said, ‘That’s a iitde long, Jumbo. Not right you should be out that long.”

“I know.”

’ “There’s rules.”

“Yeah. But the company, you know.”

Pause. Somewhere out there, Deere knew, Backpack was shaking his head, blinking awake, looking at his own trip report, watching the road. “Yeah,” said Backpack. “I knowSejp

1_:-:“Yeah,” Deere repeated. The animal growled near the camp, hanging back. Deere turned on the wipers and watched the water roll across the windshield, and for a second it all went dark. Now and again the animal swallowed him, just jumped up and grabbed him, sucked him down, and then he’d blink out, and the animal sleep would wander away, watching.

1 ‘‘Take care, Jumbo. My daughter, man, she does love that jelly.”

“Heh. Mine too,” said Deere. He put the mike back and realized his face was getting wet. and rolled up the window. He turned on die radio.

(Teen Angel, can you hear me?)

“Hey, man, don’t fall asleep on me.” David Morgan turned up the radii) and shifted his foot. Ted Chamberlain moved a bit in his sleep and looked up at the driver of the small Ford Eseoit from underneath a mess of black hair that had fallen over his face. David was getting tired of depressing the gas pedal, but the Escort was not legendary for its accelerating prowess, and he had to stay pretty heavy on the gas to maintain a good speed. They were travelling east on Route 4.

Ted blinked a few times and rubbed his eyes. “It’s raining.”

“Yeah,” said David. “Cut me some slack and talk to me.”

Bj'What are we listening to?”

“Oldies,” David said with a grimace. He felt filthy. They had been driving for hours since the last stop. Not eng now. He ran his fingers through his red haii and felt like washing his hand afterwards. He was drenched in the kind of dry sweat that comes from sitting all day.

Ted reached down to the floorboard and rummaged through the mess of candy wrappers and crumpled fast food boxes to find the portable stereo. He lifted it to his knee arid popped the cassette drive open. “What do you want to hear?”

“Anything,’ David said, as he indignantly flipped the car stereo off.

'Eureka. ’ Ted said coolly. He held a tape under David’s nose. ‘Aerosmith.”

“Fair enough.” David watched the white lines disappearing under the hood as he listened to Ted popping the tape in and punching the play button. After a moment Steve Tyler’s wailing voice pierced the air with “Walk this Way”—briefly, because Tyler was immediately struck by an electronic seizure that warped his voice and dwindled it iowri to something that might have come from the mouth of Mr. Ed.

David shook his head “What did I say? Hm?”

“I don’t have the faintest—”

“What did I-say? Alkaline. Buy alkaline. House brand batteries, ‘no, those are just as good, David, they’ll last us ’til we get there.’ Hm? And I said—”

“They were cheaper.”

“Just so long,?’ said David, “as you know I was right”

‘ Right you were, oh wise one,” said Ted, putting the stereo out of its misery. The long-haired student looked out the window and back at his red-haired friend. “So. How long ’til we get there?”

“Oh,” said David, “about an hour. Maybe an hour and a half.”

“Think your Mom’ll be up?”

“She’ll get up. You know her. Soon as we hit the house, she’ll have a full-fledged barbecue ready ;n a quarter of an hour.”

“Think she’ll be ticked that we took a three-day weekend?”

“As long as I get the grades, I can do what I want You’ll see.”

“Cool.”

F^She is cool. Not the slightest bit like my dad.”

“I’ll take your word for it. What does he do?”

, ‘-‘You don’t want to know,” said David, which was what he usually said, and it tended to suffice as an answer. Fact was, he wasn’t completely sure what his dad did, and he didn’t much care. Dad was a distant person who tried really hard and sent money and just wasn’t around that much. And he could live with that.

They were driving to the Kamptons on a sort of musical whim. David had decided on Wednesday during Romantic & Victorian Poetry that Friday’s class wasn’t so important, after all. He had decided this because his mom had sent him a letter, the usual care-package-and-a-check, and she had included a clipping from the local paper advertising a two-day Horror Fest-o-Rama at the art theater down the street from a community college where Mom took art classes. Mario Bava, the Italian horror-meister of the 1960s, was to be showcased. “Fm not sure why,” the woman had scrawled, “but I thought you might be interested.”

“You bet I’m interested,” David had said, almost screaming it aloud while Professor Gregory chanted on about the neurotic Percy Shelley. “Hell, yeah,” he had answered to Ted’s incredulous questions. “Mario Bava! Babes in black and smoky crypts! Billowing smoke and vampires! And you should see the women at these things, man. Slender, dressed in slinky black, like refugees from Black Sunday. Suicidal-looking, but distinctly cool.

That was pood enough tor Ted. So here they were. They had gotten off late on Thursday and hadn't left Davis College until late afternoon, despite all intentions. But now they were nearly there.

“Not a problem*’5 David said again. ‘We crash, we eat well tomorrow, we hit the Fest-o-Rama tomorrow night, and we ogle the suicidal babes.” That was three minutes before they hit the jelly truck.

Three minutes is a long time. Alex Deere was still awake. Three minutes later on the curve, the animal sleep had pounced and devoured.

Alex Deere heard the hollow crunch of the guardrail ripping at the bumper and the snapping of the posts on which the railing stood. Above the grating of the chainlink fence grinding against the radiator grille he made out two sounds, like shotgun blasts: the tires blowing. He realized he had been sleeping and was already fighting the wheel.

In a highway accident, time becomes syrup. It is thin in parts and melted, and then the cooler parts grab you and stick to you. Deere saw his hiinds streaking like arcs of light on the wheei, saw a glint of metal from die front of a Ford Escort, saw two white hands down there, way down there in the Escort, a world away, fighting a steering wheel. He saw two eyes, the driver’s eyes, looking out from under shoulder-length red hair. Alex watched and for a thousandth of a second felt like he was in the Escort, the dorky little zero-to-sixty-in-three-minutes Escort and he was a long-haired kid trying to steer out of the way of a tractor-U-ailer coming Tike a locomotive over a flimsy sheet-metai guardrail, the fence twisting and rolling underneath.

(And yoonouuuu went running baaaack. . . )

Crunch and munch. Like candy, like foil on the candy bar and Alex was eating it without taking the foil off, foil grinding into the chocolate and scraping Alex’s teeth and making his nerves sing with agony. Crunch and grind, and Alex tore the truck back in the direction of the highway toward his side of the guardrail even as the Escort was coming under the bumper. The flat wheels snagged the twisted guardrail. Time snapped thin and thick. The passenger side of the Escort slammed against the edge of the tractor, the shredded tractor wheels glancing off the ruined guardrail and getting wrapped up in the chain-link mesh.

Alex felt a great thrust from behind and realized the trailer had taken on a life of its own, bucking like a bronco, trying to throw him, trying to come through the back of the tractor and giving up and going around instead. The trailer twisted on its gigantic hitch and headed over the guardrail as Alex watched the windshield.

(Slip the juice to me, Bruce!)

The Escort wrapped around and wedged itself into the open seam between tractor and trailer and the two vehicles crunched on the slick concrete, tumbling in a long somersault off the ramp.

Freeze it. A moment in time like any other. Alex Deere is staring out the wet windshield looking up at the stars. The view out of the busted Escort windshield is of a narrow V between tractor and trailer. Two vehicles have become one, and they are frozen as they tumble through the air. Someone on a hill nearby is watching, and the concrete is exploding beneath his feet as he begins to run.

David Morgan thought: Streamers. He saw streamers in a dream once, after a pileup he narrowly escaped way off on Gulf Freeway coming out of Galveston, and he dreamt of it for months. In the dream, there were hundreds of cars crunching into one another like a soul train, and there were people hanging out of the cars, waving their arms, standing by the side of the freeway baking in the Texas sun, and off their arms and heads flew red streamers, long red ribbons whipping in the wind, trailing off the arms and heads and feet and out of mouths and off the jagged teeth of gaping windshields, streamers! And now he saw sireamers and heard distant popping and felt mass and bone and metal and plastic moving together.

(Warm... leatherette. Warm... leatherette.)

And again something else, not the exploding concrete under the feet of the giant man who hadn’t made it there yet, something else, a new sound, a screaming that meshed and chewed in with the screaming people, a sizzle of lire and gas lines bursting and pouring down.

And something else again: the thin metal of the trailer tearing open like a cookie box, and out of it begin to pour a million jars of grape jelly.

Crunch and sizzle, and now a whoosh, air and gasoline and fire, ripping through the gas tank of the tractor. A million jars of jelly raining down on and around the wreckage onto the asphalt. Glass jars busting and grape jelly flying through the air with bits of glass, streaming across the asphalt and mixing with gasoline.

Nothing you could write down, not a krak like a mortar or a blam like a firecracker, nothing you could describe unless you were there, pinned under the wreckage, nothing could put a word to the sudden, sharp, lacerating explosive sound of compressed tanks and gasoline making themselves known to the world at large.

Robert Bruce Banner’s feet hit the highway as a wave of flame seared past him and the sweat on his chest erupted in steam. He felt something hot and sticky against his bare feet.

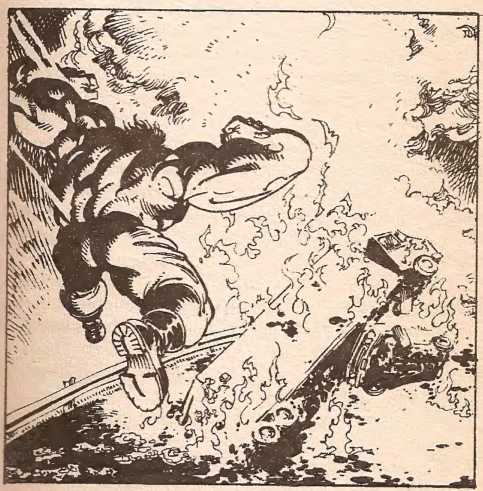

The highway was aflame, gloriously garish. Grape and glass burned and exploded from the jars. As soon as it hit the ground, the wave of glass cooled to the touch of the wet asphalt and hardened into a giant sheet of purple, flaming jelly. The Hulk felt himself slip on the lake of jelly and go sliding for an instant He righted himself and kept moving toward the massive flaming wreckage. The night sounded like a war zone, jelly jars popping ever} second.

Through a curtain of fire and popping glass the Hulk could see a little car, streaming with something dark and on fire and someone was in there screaming.

(Won’t come back from Dead Man’s Cuuuurve, , .. )

The Hulk reached the week and was putting his hands on the hot metal of the underside of the trailer when he stopped. Flipping everything over wouldn’t solve anything—he looked over at the crumpled Escort and realized any more twisting would finally crush whatever was left intact inside. He heard a honking and the screeching sound of rubber and looked over his shoulder to see a Mercedes just reaching the lake of jelly glass. The Mercedes valiantly fought the spin but succumbed, careening over gas and glass towards the wreckage. The Hulk watched the German box spinning towards him and thought, Airbags. He slammed his heels into the still-hot glass and felt traction where the sheet cracked.

As the Mercedes reached arm’s length the Hulk bent down and grabbed the front bumper, slinging the car side ways toward the side of the road, as gingerly as one could reasonably sling an out-of-control Mercedes.

Screams.

In the distance, ne could hear the sound of sirens. Someone had reported the crash. The Hulk looked up at the wedged-in Escort and hopped over the wreck to the other side, getting a clearer view of the windshield.

Two people. One of them was moving, beating at the dashboard, pinned, the other slumped over the wheel.

Robert Bruce Banner owned several doctorates, none of them medical, but he knew that moving people before the paramedics arrived was, in the abstract, a bad idea. Then a rumble and sizzle reported from the tractor, a tank still full and beginning to shake. The Hulk cursed loudly. The hell with the abstract, he had to move them.

The Hulk reached up his giant green arms and grabbed either side of the V in which the Escort lay wedged between the tractor and trailer. He began to push the edges apart, careful not to move too fast.

Moving giant objects for the Hulk could be like surgery for a normal human. Anyone can take a knife and rip a torso in half—the trick is to deny your strength, hone it and wield it carefully. The Hulk pushed the entwined meta! apart as a surgeon would separate tissue and winced when the Escort began to move inside the V. Gas trickled faster, and as the Hulk pushed the V open wider he let the car move gently iown, tumbling almost softly upon his knees. The Hulk grabbed the metal of the car door with one hand and pushed the tractor-trailer back, then began to step away.

The truck began to come with them. The two vehicles had joined one another, were determined to die together, and they had taken their iast few moments to wrap as many little arms of metal around one another as they could. Flames began to snap and rise, and the last tank began to change color. The Hulk grimaced as he found he had to tug and twist the car a bit to dislodge it, until finally there was only some resistance, and then, when what the Hulk thought was the rear axle of the Escort finally tore away, the Escort jerked towards him. A scream shot out of the Escort and the Hulk saw the kid inside, staring at this giant mass of green muscle carrying the car away.

Through the flames and grape jelly, not leaping but stepping very fast and very carefully, so as not to slip on the hot glass, the Hulk moved off to the far edge of the .shoulder and prepared to pry the Escort open. An eighth of a mile away, die fire trucks had begun to arrive. The ^mbulances were back there loo, and they were not getting n.

There is an apparatus called the jaws of life. It is a large machine, basically a big wrench used to rip a car open to extract whatever soft bodies might be inside. The jaws are a favorite tool of firefighters and emergency medical teams. The Hulk, who had travelled to distant planets and beaten up sundry weird aliens and world-devouring cosmic beings, found himself momentarily horrified at the thought that for this Escort, he was the jaws of life. He looked over his shoulder and saw the V where the Escort had lain, disappear behind a curtain of fire in the middle of the jelly lake.

The Hulk peered through the driver’s side window and tried to ignore the blood and screams. The Escort resembled not so much a car as a deformed taco shell, the front and back twisted up, the hood crumpled. Mercifully, it was the underside of the Escort that had been in the vise grip of the V, and the roof, while damaged, had not been crushed. The real damage, the Hulk shuddered to think, would have come from the seats themselves, and the dashboard and floorboards.

Overhead the Hulk heard the sound of a helicopter. LifeFlight. Thank God.

Banner grabbed the roof of the car with one hand and pressed down on the bottom of the driver’s side window with the other. The metal protested. As if peeling the top off a sardine can, he tore the metal back, until he pressed the roof down behind the car. He leaned over and put one hand on the driver’s side window and the other on the far window. This meant his arm barely brushed against the dark-haired kid in the passenger seat. The kid wasn’t screaming anymore, and if he was in pain, he didn’t show it. The Hulk could not tel) how badly damaged the kid’s legs were.

An awful, terrible noise came with the widening of the car as the Hulk gingerly pressed the two sides apart, just a bit. Just enough to see the kid’s legs. If they were too badly trapped he would do no more; he would wait like a good little physicist for the real doctors to get here and do their thing.

The Hulk almost cried out in joy, considering. When he pushed the car door away he saw a wonderful sight: the legs were indeed broken, but they were not trapped or impaled or imbedded. The Hulk reached down and picked up what appeared to be a wallet and stuck it in his pocket, and in an instant lifted the dark-haired, bloodied kid into his arms and began to carry him.

“StopI” came an amplified voice from overhead as a searchlight struck the Hulk’s eyes. The helicopter came around and dropped to a height just about equal to the Hulk’s eyes, not twenty feet in front of him. “Stop what you are doing.”

The Hulk stood still, ignoring the bright light. He knew what was going on. He knew what he looked like, a giant, green monster holding a bloody kid in his arms. He knew they were scared to death. After a moment the HuLc nodded to the pilot and waited for the searchlight to dim, and he could see the pilot’s eyes. He held his gaze for a long time, not shouting, because no one would hear, and he would appear to be roaring. He held his emerald gaze and hoped that he could convey enough to say, This boy is in trouble. Come get him. The Hulk gestured with his head for the helicopter to set down. The pilot stared at him from beneath a shiny helmet and then, slowly, did as the Hulk suggested.

In less than six seconds two paramedics jumped from die grounded helicopter and ran to the green giant and lay a stretcher on the ground. In his arms, the kid moved, tumbled something. “David ..

The paramedics stopped a few feet short. One of them was a young kid, not more than twenty-two, and he pointed at the stretcher. They don’t know I can talk Mought the Hulk. “I don’t mean any harm,” he heard ionise if say, and he winced at the sound of it because he - sunded like Michael Rennie in The Day the Earth Stood Still. They shot Michael Rennie.

There’s no time,” said the paramedic, shaking his head. "Help us get him on the stretcher.”

As the Hulk lay the kid on the stretcher the paramedic began to strap him in. “Any others?”

The Hulk shrugged. ‘ ‘Driver of the truck is dead. No question.”

The paramedic frowned, looked back at the freeway where the smoking truck lay, then at the Escort. “He keeps asking for someone. Was there someone else in the car?”

“Yeah,” the Hulk nodded. “Yeah.”

The paramedic nodded again and his partner signaled to the helicopter, which lit and began to move toward the chopper. When it was overhead the paramedics ran the lines from the stretcher to the chopper's underbelly. The other paramedic scrambled up a ladder and the younger one turned to go, then looked at the Hulk. “You did good, mister.” In a moment the paramedic was in the cockpit and signalling with his thumb to the pilot.

The freeway was a nightmare of lights and sound, fire trucks and ambulances and a gathering crowd of onlookers. The Hulk stepped toward the shadows, toward the feeder road, and stepping under the underpass he fished the wallet out of his pocket. He opened the wallet and found a license.

David Morgan. The Hulk sat in the shadows under the overpass, staring at the wallet. He read the address several times. When he was sure he was not mistaken, he shook his head in shame. After a long moment he looked up, peered out from under the overpass, across the freeway to the hill on the other side. There, a man stood, with a pair of binoculars. Watching him. The Hulk was not surprised.

Worse and worse. Worse and worse by day and night.

Inal

.................... 111 mm i "liniinii1 w

phrase and smiled to herself as she made her way to her dressing room behind the Langley Theater. It was one of those phrases that starts on some clever critic’s lips and ends up in a column, and then, because it was short and clever, starred getting said everywhere. The Americans, especially the “educated” types that frequented Broadway, were as captivated by the appearance of cleverness as they were with art, and so anything clever became conventional wisdom (conventional cleverness?) and got repeated. It didn’t even matter that Nadia wasn’t playing Electra but Antigone—in a revival of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, no less—the phrase stuck because it was terribly clever, or seemed to be. (Nadia reminded herself that the Americans were captivated with saying “Where’s the beef?” for years.) She knew without doubt that her producer laughed every time he heard the E'lectra phrase, and in his head, if she could listen, would be that distinct ka-ching sound that cash registers used to make.

Nadia Domova, the actress walking through the cavernous hallways behind the Langley, the blonde Russian with the voice and eyes of Dame Judith and the legs of Brigitte Bardot, was on the rise. She stepped through the corridors with more authority than she had in years, watching with a hint of concealed amusement as people looping cables backstage got out of her way as if she were on fire. Antigone was into its fourth straight sold-out month and going strong. People could just keep on being clever.

ouming, the people were saying, became the hell

out of Nadia Domova. Nadia thought about the

Nadia turned a comer and felt her face flush. Her dressing room door was open, and standing in the hall, lit by the yellow lights from the room, were three men. They were speaking in hushed tones and looking up and down the 2orridor as they talked She knew two of them. One Was her director* Richard March, ^nd he was nervous, because he kept rubbing his back at the lumbar region, a reminder tc all that he had aches he wouldn’t talk about. (Everyone in the theater was chronically dramatic.) The ne t man wore a charcoal gray suit that seemed to encase him like a. coffin, and he had a face of stone. Though some of the murmurs came from his mouth, his face barely moved when he spoke. That, Nadia felt sure, was

11 C°P’ ^ if she were at home, she would have called him KGB.

The third man was a breath of fresh air.^Greg?” Nadia tilted her head as she walked and tried to make°the name ask all the questions. Greg Vranjesevic was nodding and had his hand on the shoulder of the cop when he looked up and caught her eye. He smiled, and she felt her stomach twist despite herself, professional that she was.

Greg was not the quintessential Russian politician, the simple gray suit that he wore betrayed a lean, muscular frame, the frame of a man whc had been handpicked to grow up to be a medal-earning Soviet gymnast before a nasty car accident put his career on hold. The story went that he had been studying all along, anything he could get his hands un, just in case he went down for the count. Wijian the time came, he petitioned for removal to the state department. It was a demotion, a terrible shame. His fam-% was horrified at their loss and practically mourned him. By the time he made Ambassador to the United States, Ire was thirty-three, and the gymnast thing was nearly forgotten—except that try as he might, he would never iook the part of a Russian politician, having forsaken the role of a walking testament to vodka and cigarettes for the look of a new breed. He also had a great smile.

Gn took Nadia’s hands in his and kissed her cheek, still smiling, but she could see the concern in his brown eyes. She had seen that look before. Her late husband

Emil used to have that look. He would kiss her and smile charmingly and then go out and someone would nearly kill him. Then he would come back and kiss her and smile again, repeated until, finally, he didn’t come back. Men lied with their mouths but their eyes were oracles.

He said, “Nadia! How is my favorite defector?” iH-“Something 1 should know?” Nadia asked, tilting her head to make the question sound almost casual.

Greg’s smile lingered for'a moment and then exited stage left. “I’ve been talking' to Richard... :”‘‘

called him, y said March. “He said to call him if there was another.”

“Another?” Nadia frowned. “Another message.^."

“Ms. Dorncva,” said the coffin man, “do you know if there might be someone upset with you? I mean, someone who might want to—frighten you?”

Nadia felt her eyes flash. “I don’t frighten easily, Mr.—?’"

“Timm.”

Nadia breathed and said cooly, .“1 don’t know you; Mr. Timm.”

Greg chuclded. “They’re the same in every country, aren’t they? Mr. Timm doesn’t like to talk much, he prefers to ask questions. He doesn’t like to talk about who he’s with. But he’s been very helpful.’* His voice was cool, his English perfect, with a useful trace of Russian accent about it, which Nadia suspected he left there intentionally.

Nadia raised an eyebrow and smiled wryly. ;“None I can think of,” she said, in answer to the question.

SE‘Well, you know,” said March, “I’ve seen this before, someone becomes a star and there’s bound to be a few fans who’ve gone ’round the bend.'’

.--.‘■■‘What was it?” Nadia asked.

Greg softly grasped her shoulder. “Why don’t we gc for a walk?’ ’

I think she should see it,’ ’ said Timm, as if this were a topic already long running.

See what ? Nadia turned to go in the dressing room door, but Greg stopped her.

“I wanted to erase it, tell you about it later.”

“I agree. ’’ said March,

Nadia nodded again and stepped inside, heels clacking on the linoleum. She looked around for an instant at the cheap chairs, the mountain of expensive flowers and" gpfe After a moment the mirror caught her eye and she almost gasped. Almost.

“But I thought you should see it,” came the voice of Mr. Timm.

There was green putly or makeup, on the mirror. Scrawled in huge, block letters was one word: haughty. ‘‘Haughty?”'

: ‘Does that mean anything to you, Ms. Dornova?”

‘ vh, come on,” said March, “that’s like asking if proud means anything to her.”

Nadia continued to stare at the word and felt for the chair behind her and sat down, never taking her eyes off of the smudgy letters. For the longest time she kept reading it, as if it were some terribly significant name to which she had forgotten ihe face. “I don’t know,’'’ : she said, finally.

ureg said, “I guess it’s not much. ' He was behind her, hands on her shoulders.

x imm stood in front of the mirror, the word haughty hanging over his shoulder like a caption. “It could mean anything.”

“Anything it means, anyway,” said Nadia. “So people think I’m haughty now?”

Greg said, “No one could think that.”

“Very helpful, Greg,” she laughed, putting her hands to her prehead. It was a nervous laugh. After a moment she said, “I think you men are scaring me more than this.”

“It’s not the first message,’-’ said Timm.

This was true. There had been a few notes before, small things that at first Nadia had almost completely ignored. Little notes left in places where she would find them, on her marks on the stage. She had pointed them out to Greg when one appeared in her mailbox at home. Sometimes they went on for paragraphs, in long strings of impossible-to-understand symbols and disconnected words. Sometimes they were short.

“People fixate on Ms. Dornova,” said March. “Fixation becomes Ms. Dornova’s audience, I guess.”

Nadia felt her composure slipping, a distant early warning blinking on the horizon, telling her her hand was shaking, and she calmly bit the edge of her finger. She had been fixated upon, indeed. She had been kidnapped, even, a few years ago. A mad mistake of nature known as the Abomination had scooped her up and taken her below ground and then, as quickly had released her.

As if reading her mind, Greg asked, “Could it be the Abomination?”

“You’re asking me?” Nadia shrugged. “That monster wanted—” she stopped, staring at the mirror. “He wanted my company. He was like a child that watches television and wants the people on the programs to come live with him. I called him a monster, but he was never angry. He let me go.” She heard a scratching sound and looked up to see Mr. Timm scratching notes with a plastic wand on a handheld computer. It was long, like a notepad, with a hinged black cover that hung down from the top.

“Just the same,??, said Greg, v‘we can’t be too careful.”

“WhatT want to know is how did he get in my dressing room, whoever he was?”

“I don’t know,” said March, shaking his head and staring at the floor, hand working the lumbar region. “The security—”

“Your security,’^interrupted Mr. Timm, “leaves a lot to be desired, if i may say so. He could have broken in in the middle of the night, even slipped by with a press pass in the daytime. There are hundreds of people working on this show, Mr, March. People can slip by; security can slip up.”

March nodded sourly. “I agree. We’ll double it. Anything for the star, eh?”

“Wouldn’t hurt,’" said Timm.

Greg nibbed his chin. “Mr. Timm, I appreciate your concern. I m aware that you would not be so concerned if not for Ms. Dornova’s—connection with me. Is there anything you can recommend?”

Timm’s mouth barely moved, but there was a shrug in the voice, at least: “Honestly? Right now I’d say Ms. Dornova should keep acting, and keep thinking, and call if she thinks of anything, or if anything else happens.”

‘ ‘Call me?’ ’ Greg asked.

A card appeared in Timm’s hand, outstretched toward Nadia in a motion that was almost impossible to follow with the eye. “Call me.”

Nadia took the card almost warily and glanced at it before putting it away. It said: julius timm. special AGENT. STRATEGIC ACTION FOR EMERGENCIES. Under it was printed a simple logo bearing the acronym safe, and under that was a locai phone number. She nodded and put the ca±J in her breast pocket. She sighed, ana smiled, looking to each of the three men. “Well.”

That s the ‘Get-the-hell-out-of-my-dressing-room’ weii, folks.’

‘ Fine,” said Timm, slapping the computer closed. It vas an almost comical movement, as if someone had put the hinge on there to make the agents feel like they still had old spiral notepads instead of liquid crystal displays. “I hope all goes well, Ms. Dornova. I’m sure it will.:.’ IL “I’m sure,” she responded. “But I do have a performance to prepare for. Thank you very kindly for your time.”

When they were gone she realized that no one had yet scraped the word off. And all through her makeup session, she stared at the word. Haughty.

Eyes, thought the Abomination. Haughty eyes. In the darkness above the theater, in the rafters, the keyboard clacked beneath long, green nails. If anyone had chanced to look up above the chandelier, the person might possibly have seen the odd creature sitting there cross-legged, back against a post, scaly hands lit by the glowing LCD. The unlucky spectator might have seen the face lit up there; a face more like an amphibious reptile than that of a man, a face with hard, green, thick skin and fins that puckered and splayed with every breath.

The Abomination flexed his fins and looked around the heights of the Langley. No one was watching. No one heard the clacking keys.

Every eye in the theater was on Nadia Dornova far below, and he could hear that voice rising through the air, commanding and defiant. The performance was going well. Antigone was having it out with Creon, the king and her uncle, who swore to execute anyone who gave a proper burial to Antigone's dead brother. The defiant Antigone had stolen into the night to scatter dust on the baking, rotting flesh, a ceremonial burial to appease the gods. And now Creon knew of her defiance, and the house was enrapt as he announced that she was going to die.

“It’s tine,” says Creon, “we are not a very loving family.”

And Oh! Nadia was brilliant. More brilliant than she had ever been before. She was on fire, and the Abomination’s nostrils and fins flared as he thought of those eyes of hers, and the fire he had once felt in her arms, all those years ago. Those eyes, those haughty eyes.

Yes, haughty indeed! Full of pride that she had become this angel of the theater to these snivelling masses, reflecting the haughtiness of all those who stared at her.

The audience, the Abomination knew, stared at her with pride, because they felt they owned her. They paid their money and they got to watch her, got to hear that voice that should have been his alone and watch that body that should have been his alone.

Breath rasped and bubbled within the Abomination’s mouth, which bung open slightly as he concentrated on entering the memorized codes. He squinted his demonic eyes and cursed at the bulk of his claws, which required him to be extra careful not to crush the keyboard, much less enter the wrong code. One slip and his claw would punch right through the liquid crystal display, and the: Abomination watched the image for a moment in his mind, the glowing crystal oozing from the sliced fabric. Later. That would amuse him later.

He tapped the keyboard again, and something about ten feet away clicked twice and hummed. The Abomination listened as he tapped a few more times. Klik-klik-humm, from various parts of the rafters throughout the building. His allies had done good work. It pleased him that they were willing to help him as much as he helped them. With each click and hum, a small jet dislodged from its cradle and lowered itself a couple of feet, titling downward. The sound multiplied itself a hundred times, throughout the theater, like a rainstorm of barely audible clicks, until at last each jet lay in its proper position.

Haughty indeed! They would learn haughtiness. The Abomination tapped another entry code into the keyboard and heard a new humming sound, saw the rubber hoses snaking through the rafters whip as the gas came online and travelled to the jets, ready.

The Abomination’s vision shifted in focus and he peered down to look on Nadia once more. Something in his gills hissed angrily as he looked at her, not anger at her, not at himself, but at whatever demon forced him into this. There she was, supple and tall, slender like a gymnast, like that gymnast bureaucrat Vranjesevic she was carrying on with. He changed his mind—he was angry with her after all. Angry that because she was beautiful and soft he could not see her, could not talk to her, because for every soft curve of her body he had scales, and rocklike green flesh, and where her eyes were soft and radiant, his radiated hatred and glowed like rubies. What had she called him? Like a child? A child?

All of them would pay, every last haughty one of them, laughing at Anouilh’s clever witticisms and laughing at their good fortune to be the Beautiful People, the happy people, the worst of the whole lot of these Americans who rape and pillage the entire Earth because they feel entitled to it. They looked at Nadia and heard her velvet voice and their eyes travelled over her body. They laughed and smiled because they owned her and she owned them, and when one owns something beautiful one surely became beautiful. That was what they thought, the Abomination was sure, and they would all learn; they were abominations just as he was the Abomination, and by the living Lord he would surely teach them.

The computer beeped twice and a timer flashed on the LCD. Fifteen seconds, it said, counting down. The Abom-lation smiled as best his warped mouth could manage, and he felt the slime stretch between his lips, bubbling as he breathed. He watched the seconds tick away, as he stared down at the theater, at all those heads, all those haughty eyes, and finally at Nadia.

And Nadia was looking at him. For a moment he froze, felt the gamma-irradiated blood chill in his hardened veins. It was an illusion, of course, just a freezing of time, a snapshot of her looking up at him by chance, not seeing him at all. Nadia was deep in her part, and he watched that faraway look and dove into her eyes, and rode them back to their youth.

God, my God, Nadia, you were so beautiful. God, my God, Nadia, how I loved you.

And they were young again and disgustingly happy, as he recalled, and she sat by the fire as he brought in more wood. She laughed at the furry cap he wore, because it was his father’s and must have been a hundred years old and should have been taken out and buried, she said, and she would take off his cap and she would kiss him. The Abomination watched those eyes, felt those eyes looking on him with love, with simple love, and he felt his throat gurgling. Somewhere in the back oFhis mind the timer beeped away, and he held the vision a moment longer, almost reaching out a scaly claw as if to tonch her.

Beep. The Abomination looked at the keyboard and at the vision and thought, No. He reached through the vision arid tapped a code quickly, and one, specially aimed jet went offline, clicking and bumming back into its cradle.

Haughty were her eyes, it was true. She was an abomination. But it would be enough, he decided, for her to watch.

Beep. A hundred rubber hoses pumped and whipped in the rafters, and sometliing began to spray . In a moment, the Abomination heard screams, and he sat still, listening, clawing the liquid crystal, and letting the glowing greenish-blue fluid run down his fingers.

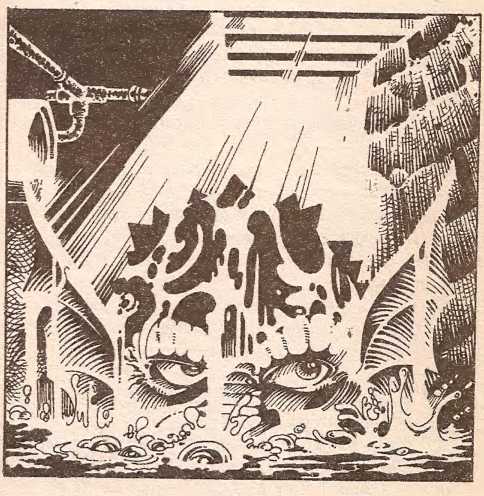

Nadia heard the first scream as she was delivering a line that always gave her trouble, and she found she had to step out of character for a microsecond in order to remember how the line went. And then the line disappeared entirely from her mind, and she struggled to grasp it, chasing the white rabbit of a lost line, trying to ignore the sound of screaming"? The line, the play, vanished- She stared out into the audience and heard a rumble of voices, questions being hurriedly whispered, and the spotlight was so bright that the audicnce looked as if it were on the other side of a cloud. After a moment the lights seemed to dim, or else Nadia’s vision adjusted, and she heard a scream again and looked out and saw a woman, in about the tenth row. She was middle-aged and wore a smashing evening gown, and she was rubbing, no, clawing at her eyes. A man next to her stood, to help her, Nadia thought, but no* he too was tearing at his eyes, rocking on his legs with his fists in his hands.

Nadia gasped now, not because of the woman, exactly, but because she saw the green cloud for the first time, and marvelled that she had not seen it before, A green mist hung in the air, floating down, and the air glowed with iridescent sparkles as the lights pierced through a billion droplets of green liquid. More murmurs, still just that one woman, screaming, and then another scream lit the air, and another. Nadia looked around in horror and saw more people howling in pain and tearing at their eyes, rubbing violendy, and someone was screaming from the back, ^‘‘Please, get it out!”

Nadia backed away, numb, tripped over a prop lamp and fell to the floorboards, and she looked over at the man playing Creon. He was backing off the stage. Nadia propped herself up too hurriedly, and saw a man running towards the stage, a stranger to her, running blind with his face in his hands. The man hit the stage and feU over. She watched his hands reach the stage as he clawed to get up on to it. Time froze for a second as she saw the man’s bald head top the edge,-and slowly lift, and then she saw his eyes.

Fused, hideously fused eyes glowing green and bub-Jbly, and the man was screaming in terror and running bund and she could not take it and scrcamed herself. Ha scream mixed with those of the man and the thousand in the theater and she looked out and saw them ah, the whole of the audicnce, on the floor and in the balcony, crawling over one another, blind, eyes fused, hands learing at one anothei and at their own faces. They resembled a large mound of worms, people without minds, squirming, irrational masses of green-glowing terror. Nadia saw the man get closer to her and she found her feet and ran.

Across the stage, off and into the corridors she ran. She felt the edge of a desk tear at her leg, heard cloth rip away, and the sound of howling terror eased as she ran, but it was still hack there. She saw her dressing room door and ran for it, thinking all the while that she should turn, head out onto the street. Someone said her name and touched her shoulder. She shook furiously and ran on, and heard again, “Nadia!”- She found her dressing room door and whipped it open.

She was just running inside when something caught her, hands on her shoulders, turning her around. She cried and screamed and looked in lus eyes, and saw Greg Vran-jesevic. Greg shook his head and held her as she shook violently and wept onto his chest. After what seemed like an eternity the shaking dwindled to a tremble, she opened her eyes and blinked as Greg asked again and again if she were all right. She knew that she was. And then she looked in the dressing room and saw the mirror and began to shake and scream again, because the message there had been lengthened by one word

It Said, HAUGHTY EYES.

Michael Cross watched the Hulk through a pair of field glasses. The glasses recorded everything he saw, feeding into the SAFE databank miles overhead in the agency’s Helicamer. Cross stood about fifty yards from where he had parked his car. He had considered himself lucky— this was the first night the Hulk had stirred from his nest in White Plains, and Cross had followed at a safe distance, watching everything. So Cross had been in perfect position to see the fugitive gamma giant desperately try to rescue the parties to one of the grisliest accidents Cross had ever seen. Cross’s eali to EMS brought the trucks and helicopters by the time the Hulk was doing his jaws of life act. Now Cross stood, his jacket flapping in the wind, binoculars pressing a crease into his face, and below him the highway still smoked aud burned with wreckage and jelly.

Cross spoke softly* the binoculars picking up the sound of his voice. “Look at that. Look at that. This is the Hulk, ladies and gents. This is the guy who rips tanks apart, that’s him, handing an injured kid over to the paramedics like he’s the Green Samaritan.”

Cross watched the Hulk walk away from the paramedics for a while and look around him. For a moment, as the Hulk stepped under a shadowy overpass, the green giant gazed around, and Cross sucked in air as the gamma creature seemed to focus up on the hill, directly toward Cross himself. But after a moment, Cross saw the Hulk look away, and slink into the shadows.

The SAFE agent watched the shadowy patch of the underpass for a long while. After a quarter of an hour had passed he saw no more movement and cursed softly. The Hulk must have disappeared out the other side. Cross decided to go hack to his car; he could chase the rabbit a bit before parking again.

God, what an assignment. SAFE didn’t pay well enough for this. Half the time Cross’s quarry hung out at home, the other half, he could suddenly leap way the hell off into the southwest, leaving Cross at the mercy of other authorities to tip him off. Sometimes it was hopeless and he could do nothing but wait for the Hulk to reappear at his home base. Sometimes he didn’t reappear; that was whenever he and Mrs. Banner moved, and then it could be weeks before intel got caught up. SAFE was very good at its job. But the Hulk was a hard man to follow.

Cross looked up in the sky. [f all went well, it would all be a lot easier very soon. They’d never have to lose the Hulk again.

Cross sighed and turned as he clicked the binoculars onto his belt and walked toward his car. He shook his head, thinking of the accident—how remarkable, that this was what it took to get a little action out of the reclusive

Hulk. How lucky that the Hulk had decided to go for a walk. Life was funny

Cross sighed as he got closer to the black sedan parked by a shadowy walnut tree at the side of the road. It was just so—identifiable. There was something bright neon obnoxious about the black suits and black cars that agency men and women utilized. Cross suspected there might be something deliberate there, in fact. Sean Morgan, SAFE’s less-than-jovial boss, was a clever man, and he knew a little intimidation, even a little encouraged paranoia, could go a long way. So they followed people in big black sedans and wore black raincoats and Elvis Costello sunglasses, just like in the movies. It all worked to the right effect.

Of course, Cross thought, perhaps the heroes were different, and perhaps they should be dealt with differently. The Hulk was not some crooked numbers runner you want to notice the black car parked a block up. With the Hulk, it really was a better idea to keep pretty clear.

Cross opened his car door, sliding into die front seat. He was about to put the key in the ignition when he remembered he hadn’t noted his itinerary in at least an hour. If the Hulk was out of sight now, another twenty seconds wouldn’t matter. Hell, with the Hulk, he could almost pack it in for the next week once the gamma giant was out of sight. Cross retrieved his notepad and pen device from his coat pocket, flipped the cover of the pad back, and began to scribble a few notes on the LCD. Typical stuff. Here, going there. Big crash, Hulk heroics. Can’t wait for GamiruiTrac to render me obsolete, yadda yadda yadda.

The SAFE agent flipped the pad closed and dropped it and the pen device back in his coat pocket. He placed the key in the ignition and heard the eight-cylinder engine turn over and begin to purr—Morgan insisted that all machinery be kept in top condition, from pocket pads to the engines in the cars. “We’re on a budget heregj Morgan kept saying,§‘and there’s no way we’re letting what we have go to waste.”

Cross was about to put the car in reverse when he reached up to adjust the rear-view mirror and saw a hand-scrawled note stuck to the glass: behind you.

Cross dropped three inches in his seat and drew his gun as he fell sideways and twisted to peer between the seats and see:

Nothing. Cross breathed for a second, rising in the seat to peer over. No one was there. He allowed his eyes to adjust and he saw what he was looking for: there was a hole in the rear passenger-side aoor, where something large lacl ripped out the lock. Something not unaccustomed to acting like a jaws of—^

Crunch. Something that sounded like a freight train landed on the hood of the sedan and; Cross whipped around again staring forward. In the darkness he saw light from the highway reflected off dark green skin, sweat glistening over green veins and muscles. -AS Cross drew his gun, he saw two giant, green arms reach down, saw ten green fingers clutch the windshield itself and tear it II away in one chunk, which the creature let fly. The windshield sailed into the distance and Cross stared at the disappearing glass. Then he felt the jaws, of life grab him by the lapels and drag him through the front of the sedan. “Drop the gun, came a deep voice.

Cross didn’t move. He held onto the gun, just as he felt knuckles the size of plums bruising his breastbone. He looked down to see his feet dangling over the hood, and a few feet below that, the Hulk’s own legs, impressed in the hood of the car as if it were a papasao chair.

£i-“You don’t seem to grasp,” said the Hulk, pulling Cross close, “that resistance is beyond futile.”

There was a human in there, thought Cross. He .vas eye to eye with the Hulk and he could see it, the red-veined eyes, the lack of sleep so evident. He knew all aiong that he was dealing with a mutated Robert Bruce

Banner, brilliant guy, but it could be so easy to-forget. But the eyes locking with his now were scary, not because they were those of a beast, but because they were those of a very smart, very dangerous man.

Cross dropped the gun.

“I’m not going to ask you why you’re following me,” said the Hulk. “You’ve followed me everywhere since New York. I’m sick of it. I want it to stop. Do you understand?’ ’

Cross opened his mouth and closed it. He nodded, slowly.

“Did you see the accident?”

“What?” Cross shook his head. Was the Hulk interrogating him?

The Hulk shook his head and stepped off the hood of the sedan, setting;Cross, down on the front of the hood. Cross winced as his coccyx collided with thi crumpled metal. “Did you see the accident?”

“How could I miss it?” Cross stared. He could tp, maybe. Yeah: Right.

The Hulk scratched ins chin, looking over the hill where Cross could still see the dancing lights from the emergency vehicles. “It’s just so .. J Have you heard of Galactus?”

'“Who?”

“Galactus. Big guy. Huge, cats planets.”

“Galactus. Yes,” Cross spoke slowly, having no idea where this was going.

“I mean planets. The whole thin? A.nd there was the Beyonder: a guy the size of the cosmos, no real limits at all. I’ve been whisked to the other side of the worl because he "wanted me to be. He could destroy the world. Like that!” The Hulk brought up a mammoth green arm; and curled his hngers, about to snap them. Cross ducked. He had heard that being too close to one of those finger-snaps could be deadly. The Hulk seemed to remember this and stopped his hand before the thumb and finger collided. “You get the idea.”

“I’m sorry, but.

‘‘You’re supposed to watch me, right?”

?-J‘Ah ... yes.®

“Right, then. Shut up.”

“Okay.’jM

[|Sj‘So here’s the clincher. The Fantastic Four, they beat Galactus with the regularity of the Super Bowl. The FF save the universe all the time. I helped beat the Beyonder. And we all rejoiced, because we used these amazing powers to stop these mega-beings. Do you begin to follow me?”

Cross opened his mouth. Tom told me to shut up. This was turning weird.

' ‘The point is, Galactus makes sense to mel Isn’t that rich? I’m accustomed to that. The Beyonder wanted to erase the world, or whatever. I can deal with that” The Hulk turned towards the flashing lights in the distance, placed his fists on his hips.Ir‘This I can’t—I can’t figure it.”

/ ¥.‘It was an accident.”

“Wait a minute. Did you call EMS Cross said, “Yes.”

The Hulk nodded, his mouth turned downward. “Good. Good.”

Good? You wrecked my car!

“Listen,” said the Hulk, turning back to look at Cross. He fished in the front pocket of his giant black Dockers and pulled out what appeared in the darkness to be a wallet. It was dark leather, but Cross was pretty sure there were blood stains on it. “Morgan’s the same way. There are things that make sense .to him. Budgets make sense to him, so do national security threats. This isn’t gonna make any sense to him. ^The Hulk flipped the wallet to Cross, who caught it and opened it up. There

was a driver’s license inside, and it belonged to a redheaded kid called David Morgan.

“Oh, no.”

“Did you know Morgan had a son?”"

“No.” Why would he? The boss of SAFE was a very businesslike man, to put it kindly.

“I knew because I knew. No big deal. But that’s him. That... was him/’ The Hulk brushed at his eyes, his voice rumbling. “He didn’t make it.”

“You ... I saw you get one ...”

“The passenger. He was lucky. He wasn’t impaled on the handle brake.”

“You pulled him out.”

Right.” The Hulk stared at the horizon. “Who cares . Just one of those things. Galactus makes sense to me, here I’m just a wrench.” The Hulk put his giant g; een hands in his pockets and slumped for a moment. “So you go, Agent Cross. I gave you that wallet for a reason, so that someone other than the police can get the news to Morgan first. Do you understand? Does that make sense to someone like you or me? No national security threat here, just a really, really bad thing. And all we get to do is open doors and carry messages. Can you handle that?o Cross folded the wallet and put it in his pocket. “I can handle that.”

The Hulk sniffed. His face was mottled with soot. “And stop following me. If Morgan wants to talk, tell him to give me a ring. But I’m sick of being shadowed. Tell SAFE you’ll just waste more vehicles and someone could get hurt.” The Hulk was already walking away, leaving Cross on the crushed hood of his car. Cross pulled out his cell phone and distinctly heard the Hulk grumble as he leapt into the air, “I want to be left alone.”

The voice rambled through the dank tunnel, reverberating through the sludgy walls and dripping pipes:

“O Lord God of my salvation, I have cried night and

day before thee___”

The creature that was once called Emil Blonsky knelt on a scarlet rug in his inner sanctum, pouring the eighty-eighth Psalm out of his heart and his wretched, Abominable mouth.

“Let my prayer come before thee, incline thine ear unto my cry,”

Once he had been a man, a man of Georgia and the Soviet Union, a soldier and a spy. And now he was this. The singer of the Psalm, cut off from the world above by his new shape and his new voice.

‘ ‘For my soul is full of troubles, and my life draweth nigh unto the grave.”

In his mind flashed images, one after the other, and he rocked on his scaly knees and tried to send the demon images away, singing out the Psalm, becoming one with the Psalmist:

“I am counted with them that go down into the pit; as a man that hath no strength.”.

Flashing images in the gamma-irradiated mind, scattering salamanders and crickets chirping, echoing the Psalm, and there oefore him, Nadia, and Georgian fields, and the Western beast called the Hulk. And all around him, beyond the sanctum, stagnant pools and smells of death and decay.

“Free among the dead, like the slain that he in the tomb, whom thou rememberest no more, and I am cut off from thy hand.”

It was true, all true, and the creature rocked on his

knees and wailed out the words, hearing them gurgle in the dripping sludge. Forgotten.

“Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit! In darkness! In the deeps!”

Forgotten by Nadia, forgotten by humanity, forgotten by his country, forgotten by God himself!

“Thy wrath lies hard upon me, and thou hast afflicted me with thy waves!”

The Hulk, that beast, and those weapons, all of them, and the one gamma gun, and he had stepped before it as his superiors told him, seeking power for them, seeking revenge for them, and what had he become? Forgotten! Forsaken!

“Thou hast put my acquaintance far from me .. ’£■

Nadia! Mother! Father! Russia! And what was he now, what did they call him, far above, where the world did not stink and salamanders did not root and he had no place?

“Thou hast made me an Abomination unto them!

‘ An Abomination!”

The word roared from the Abomination’s mouth, tearing through the caverns below the city and bouncing off the bricks and pipes, frightening secret unmentionable crawiing things into the cracks, and lie rocked violently on his knees, claws before his chest. The creature threw out his hands to his sides, and cried out, gurgling and cacophonous:

?/‘An Abomination I shall bel"

For what seemed like an eternity, the Abomination sat, claws dangling at his sides, leaning back where he knelt. He listened to his breath slowing and the delicate timing of the drips from the pipes. As his own subsided he heard breath from elsewhere in the sanctum and opened his glimmering red eyes. ‘?Who is there?’ ’

A figure stepped from the shadows, and in the dimness the Abomination could see the trim figure of a woman, black ha'r pulled back to reveal a gaunt, serious face. She answered, “Sarah Josef, comrade.”

His words came slowly. “You have been watching me.” It was neither a question nor an accusation, merely an observation.

“The eighty-eighth Psalm, yes?” The woman stepped closer and dropped down, sitting on her haunches. “The Psalm of the forsaken Abomination?7 ’ She tilted her head and he rose in his place, and even though she stood up he still towered over her by at least a meter.

“Yes.”

“Good news. We have not forsaken you.”

The Abomination made an expression approximating a sneer and nodded, and walked over to a large console built into a grungy wall. The console seemed to be an organic part of the underground itself, a dark tumorous piece of technology. The Abomination sat on the stool that seemed to grow from a dark, metallic arm jutting from the dripping wall. He tapped the keyboard and the monitor came to life. “No, you have not, my friend.” Sarah ran a finger along the edge of the console and regarded the dripping walls. “Your—sanctum—is to your lilting?”

“Yes.”

“So lonely,” she said, with u strong note of care in her voice.

“Not always,” said the Abomination. “Once there was a city here, in the tunnels. A city of the lost and forgotten, the huddled refuse of the world above. And I was their comrade and their protector. I told them stories and they accepted me as a man and a brother.” More images flashed in his head, the unmistakable sound of gunfire echoing in the tunnels, bodies slapping against the wet concrete, screams of innoccnts. ‘ ‘I was used by enemies above as an excuse to clean the tunnels out. Even the Hulk had a hand in it, an act I would likely have thought below Bruce Banner, who never had the stomach for slaughter. All of them,”J he whispered, “young and old, women and men. My family Tom by bullets from crooked police in riot gear. No, it was not lonely then. But now it is a tomb.”

“All of them?”

He looked up. ‘ Some of them survived. Scattered deeper in the tunnels. I do not think we will ever be together again. People learn lessons when they feel pain. The lesson my underground family learned was not to trust. Not to feel safe.” The green lip curled. “But I will have my revenge.”

She shook her head, and the barest hint of a smile appeared. “I think you need a little light.” .“My time for light, my dear,” said the Abomination, as he read the files that scrolled past his eyes, “is past “At URSA we believe the past can come around again.”

“Who knows? You may be right,” said the Abomination. Who knew, indeed? It had beer Sarah who had approached the Abomination. When she found him below the streets and spoke to him in Russian, he took one look at her and her standard-issue sidearms and nearly squashed her like the tadpoles he expected to feed her to. But she identified herself, not as KGB, but URSA. URSA was a new group, made up of KGB refugees and political discontents hellbent on a familiar ideal: a return to the strong-military, Communist, West-hating Soviet Union of old.

“Bah,! the Abomination had said to her then. “The Soviets hung me out to dry, What do I want with a return to that regime?”

“Not that regime,” Sarah had replied after she found her breath and began to explain herself. She had recovered from nearly being strangled. The Abomination found her refreshing, and that is why he let her talk. ‘ ‘A new regime, a purer Communism.”

“7 am not interested.”

“Listen to me and tell me again when I’m finished, she responded. “It is at great expense that URSA has located you and I will not return until we have talked.’’ The Abomination looked around, as if he had other things to be doing. “Talk.'’

The agent composed herself before beginning. She wore a gray jumpsuit and she stood with her hands on her hins, an authoritative stance. “Bad deals happen, |2j she said, “when only one side benefits. The other side feels used, cheated, and finally refuses to cooperate.”

“Yes.”

“Good deals happen when both sides benefit, multiple party deals when all sides are satisfied. URSA understands this and wishes to make a deal with you. As a gesture, shall we say, for the.old regime’s mistreatment of such an agent as Emil Blonsky.”

The Abomination tilted his nead and stared at her. “What you may have heard ii some seminar could not possibly even hint at the trutnSB®

She stared at him, and the Abomination detected the slightest tremble in her voice. “I think you are wrong about that ’ ’

“Go on, little girl/'

“It is our understanding that you bear something of a grudge against the United States and especially against the Hulk.”

“You are underinformed. I bear a grudge against almost everybody. I find it easier that way to keep them all straight.”

“All right, then,” she said. ‘Then at least we’ll share a common enemy or two. URSA would like to see a little chaos here. You enjoy chaos, I understand. Something you said a while back about bringing it all down around their ears.”

“I did say that.’fi

“We can help you. Whatever you want. I’m in charge of the American theater and you, Emil Blonsky, promise to be my most powerful ally.”

“You’ve got to be joking.”

There it was again. A tremble, faint, hidden back there, a personal stake hiding behind the austere mask, eveiy agent’s Achilles’ heel. “Why do you say that?” The Abomination strode over to stand before her and he crouched so that he could look her in the eyes.. She barely flinched when she was struck by the rank breath that flew across her face. “You want me to be an agent? For you? You and this URSA of yours? I am through with serving masters, and I do not see anything here that is about to change my mind.”

“We can help you, ’ she said, suddenly more vulnerable. “Helping one another, we both benefit.”

‘ ‘Yes, yes, you said that. Very nice speech, little sister, but what is it, why are you here? What is going on? You’re not afraid of me, I can tell that.” He studied her carefully. “You think highly enough of yourself to feel confident you could escape me if I tried to kill you again and I don’t think you frighten easily, so what is it? So I answer no, and you ask again, and still I say no, and you go away and that’s that. Yet here you are, trembling.”

It was true. She was. She averted her eyes like a junior officer being dressed down.

“You want me to join you—why? Why me,” the breath blasted in her face, ‘really?”

“Because you and I—”

“What? You and I whatT’ The Abomination waited for a second and looked at her. He had had enough torturing of this girl for one day. “Go home, little girl. Go tell your masters that a resurrected Soviet state would do me as much good as the old one did, and I am not interested.’ T-

She slumped only slightly and turned, and maneuvered out from the space between the Abomination and the wall. Sarah moved away, towards the ladder leading

up to the world of light. The Abomination turned and sat on a pipe, contemplating the dank water.

Her hand was on the first rung and she was swinging herself up to the ladder when he muttered. “Sarah....” She stopped and hung there looking back at him.

' ]‘iSarah Josef did you say?” >

She hung there still, staring at him, only the white knuckles showing her edginess.^j‘Yes;”

“Come back, Sarah.” She dropped to the ground and the dank water splatted out around her feet..

“I set,” he said. So long, so: very long, but if he-reached back, yes, there was still pain there, too. So many other pains abounded, but yes, it did still ache a bit, didn’t it? “We do share a bond. It is revenge you wan!;”

“Yes/’ she said, looking up at him. It seemed to him she was looking at him like an uncle. ‘iRevenge I think we both would like very much. Every side, benefits.”

The Abomination nodded his massive, scaly demon’s head. “Very well, Sarah Josef,” said the gamma creature. “Tell me more about this URSA. And tell me about yourself.’^

And that was the beginning of their curious relationship. Indeed, URSA had taken good care of Sarah Josef’s new charge—-they had set up his sanctum below New York exactly as he had requested, had even helped him set his own plans to work, beginning with the assault on the Langley Theater.

Hgjsrhe Langley assault proceeded to your liking?” j.f “Perfectly,;1^ said the Abomination. “The equipment was marvelous.”

Sarah looked at him and reached into a' zippered pocket and retrieved a disk, and laid it on the console.

‘ ‘My employers want me to reiterate that we hope you will have as much success holding up your end of the bargain with us* ’

The red eyes flashed as the Abomination slid the disk info a drive and began to tap at the keys. “Tell them you

have nothing to worry about, Sarah. I am grateful for your help, and find it serendipitous that so many of our goals coincide.-’’ He looked at her carefully. She was young, really, as young as Nadia had been when they had gotten married, as young as he had been, all those years ago, in Istanbul, when his career had begun its downward trajectory. “We both have something personal in this.”

‘‘You will have a new home, EmiL You can come home when the new order is set up, and—’ ’

“Let me tell you,” he hissed, as a series of names and addresses began to flash across the screen. “Let me tell you what kind of home I would like to return to. I would like to see a Georgia that recalls its rich past. I would like to see a Russia that remembers Alexander Nevsky as much as it does the Prague Spring. A Russia that looks and sounds more like the land of the firebird than it does like the land that lost millions of troops for nothing in the sands of Afghanistan. Perhaps the dream of URSA, perhaps this renewed enmity with the United States will help your dream, but that dream is not mine. I will not return until my home is what it was.

“But—”

“Yes. You know what that means, i will not return. I will help you and you will help me, but I am this now, just as Russia is this now. Stop talking to me about dreams of a new Soviet system. I am the Abomination. 1 have my own destinv.” He hissed again and tapped the keyboard and it went dark, and the sanctum plunged into dimness again. “Go. I have heard your message and you have nothing to worry about.

After a moment, Sarah nodded. Her eyes, he felt sure, spoke paragraphs of almost unbecoming warmth: No, uncle, there is new hope. “Very well.”

As she left he said, “Your father was a good man, Sarah Josef.”

The creature that had once been Emil Blonsky turned back to his console and began to draft a scries of letters.

He had URSA to thank for the complete list of proper recipients.

Betty Gaynor tapped on her lectern as she looked at her notes for a brief moment and looked up again. ‘ ‘So what do we, know about the end of the world?” She stepped away from the lectern, sweeping her gaze over the students. About half of them were daydreaming or scribbling on paper; perhaps some of those were taking notes. She was pleased to see the other half actually seemed interested.

“Hm?” she continued. “Genesis 6:6. ‘The Lord was grieved that he had made man, and his heart was filled with pain.’ Grieved. The almighty makes the earth in five days and likes it. He makes man on the sixth, rests on the seventh, and out of all the things He creates, He comes to regret man. He looks down on us and grieves. Think of that. What does it mean to grieve? Generally, we feel a great loss. We grieve our lost loved ones because they are no longer there, we’re missing the past—” she looked around ‘—and we miss the future that might have been. But for God to feel grief? His heart is filled with pain, why?” She paused, flicking her wrists to indicate she’d like a response.

None came. Betty put her finger to her lips and scanned the selection of students who were paying attention, half-enjoying the deer-caught-in-the-headlights look that came over an entire class in fear of being called upon. She considered calling on a Victim, one of the unfortunate students who had not been paying attention and only now were looidng up, out of sheer nervousness about the sudden silence. But truth be known, that wasn’t really all that fun. Well, maybe the first couple of times, but after she had gotten that out of her system, she preferred a decent discussion.

She decided to pick one of the Mouthers. That was her word for students who sat there, mouths slightly open, words waiting to come out, but kept back by—what? The same force, obviously, that caused a lot of the Mouthers’ hands to lift iust centimeters off their desks, but denied them the ability to lift their arms any further. One like ... “Clara?”

Clara Luici coughed and a flutter of mild laughter swept the room. She looked back at Betty, half relieved at being called and half imploring God to make it not so. Betty waited a moment, watching Clara and her librari-anesque blouse and large glasses. Amazing, she thought. I’m looking at myself. Strip off a few years and a whole universe of trouble, and it’s me.

“Ma’am?”

“I’ll rephrase,” said Betty. “The chronicler says that the Hebrew God was grieved about making man. Not regretful, but grieved. How does that make sense?’ ’

“Um.’ Clara stared, and Betty-could see the wheels turning. “He can grieve if He wants to, right?” Laughter. A flash of personal grief rolled over the student’s face, fear that the professor might not appreciate a bit of wit. “I mean, you can grieve someone who’s not gone/’ Good. Betty tiked her head. ' ‘What do you mean?” “Like you said. We grieve people who are lost—but the real pain, or maybe a lot of it, is the loss of opportunity, God is grieving over what humanity could have been.’