INTRODUCTION

“A Deep Scar on Our Hearts”

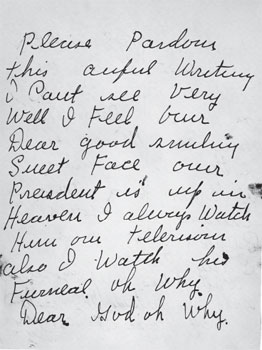

Gertrude McMurty to Mrs. John F. Kennedy, November 28, 1963, Adult Letters, box 11, folder 88, Condolence Mail, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, Massachusetts (hereafter John F. Kennedy Library).

On November 23, 1963, a day after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Katherine Dowd Jackson sat down in her home in rural North Carolina and took out her “letter box”—a cardboard suitcase where she kept white-lined paper and a pen for important occasions. Mrs. Jackson had a third-grade education, but she enjoyed writing. She was moved especially at this moment to express her deeply felt sentiments. “Dear beloved one,” she began her letter to Jacqueline Kennedy.

She wanted Mrs. Kennedy to know in the “sad[d]ist moment of your Life you have my great symphy.” “I know you are suprized to know,” Mrs. Jackson added, “I am a Negro woman.” An intensely religious person, Mrs. Jackson had drawn in the past twenty-four hours on her faith to make sense of the President’s death. “This marning God spoke to me,” she confided. He had told her that the President had done “for his Country what God did for his World[.] They killed our Lord an Father. an now they have killed our Presentend an Father. We loved him but God loved him best.”

As Katherine Jackson carefully crafted her message to Mrs. Kennedy, thousands of Americans across the country were writing similar letters. “What can anyone say at a time like this?” asked one correspondent. Few had any answers but many felt an urge to sort out on paper the storm of emotion unleashed by the President’s assassination. “As no other First Family has done, you all have come into our homes and touched our personal lives, across the breadth of America. Your voices, your faces, your thoughts, your daily activities…were personalized for us,” one woman reflected.

Almost a half century later, the events of November 22, 1963, remain a vivid, searing memory for millions of Americans who still recall precisely where they were when they learned of the President’s death. Kennedy served as President of the United States for little more than a thousand days. Yet his brief term in office and his shocking assassination deeply touched people of all walks of life, and of every social class, economic station, political sensibility, region, religion, and race. Whether they adored, were indifferent to, or frankly disliked JFK, countless Americans shared the feeling that their own lives would never be the same after their young President died so violently.

The nation has changed profoundly in the decades since President Kennedy’s death, as have the lives of all who remember those fateful days. Many of the schoolchildren who raced home on that Friday to discover grieving parents are grandparents today. The “new generation” of World War II veterans that Kennedy’s election brought to power has now reached old age. The President’s two younger brothers, Senator Robert F. Kennedy—himself a victim of assassination in 1968—and Senator Edward M. Kennedy, are both buried near their brother in Arlington National Cemetery. Wars have been fought. The scourge of legalized segregation has been repudiated. Access to fundamental political and civil rights has widened immeasurably. Fashions and mores of all kinds have changed. And yet for many Americans a filament of recollection easily brings back the incandescence of the early 1960s, when the nation appeared in some ways as bright and as full of promise as its handsome President. Millions still recall how in the passage of a single moment, much of the confidence, energy, and hopeful idealism that Kennedy appeared to exemplify were suddenly swept away. As one young mother predicted shortly after the assassination, “Surely this generation has a deep scar on our hearts which we will carry to our graves.”

That scar has inevitably faded in the nearly half century since the assassination. Time has dimmed once vivid memories of the nation’s first “television President”—a man whose verve, intelligence, humor, and grace captivated the public. The personal and political mythology burnished in the first years after the assassination have rightly given way in the ensuing decades to a much more complex view of President Kennedy and his administration. Indeed, the pendulum has swung so far in the direction of a more sober, more stark assessment of Kennedy that it is difficult to evoke today the soaring idealism, fresh hope, and sense of possibility that many Americans saw in him. Still, whatever history’s judgments about the merits and consequences of those expectations, there can be little doubt that millions of Americans who lived through the Kennedy assassination felt that they had experienced a calamity that they would not forget.

A largely unexamined, and never before published, collection of letters to Jacqueline Kennedy stored in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library vividly brings to life what the President and his death meant to thousands of Americans in the days and months following the assassination. “How does a nobody write to the wife of our late President?” asked one woman as she began a letter to Mrs. Kennedy four days after the death of JFK. In overcoming her hesitation, this letter writer resembled more than a million and a half other individuals who wrote messages of condolence to the former First Lady. The President died on a Friday afternoon at 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time. The following Monday, mail delivery to the White House brought a mountain of letters—45,000 on one day—from bereaved citizens, many of whom had sat down within minutes or hours of the assassination to share their grief, shock, and sense of outrage. Piled into cardboard boxes, and then stacked, these containers soon stretched from floor to ceiling, taking up space beyond the offices where “social correspondence” was normally handled and spilling out into the White House corridors. The volume of mail quickly overwhelmed Jacqueline Kennedy’s small White House staff, which was nonetheless instructed by the Pentagon to open every single item for “security reasons.” On one occasion, loud ticking from a package raised anxieties, until the box was found to contain a wind-up toy sent from Germany to three-year-old John F. Kennedy Jr.

Within seven weeks of the President’s death, Jacqueline Kennedy had already received over 800,000 condolence letters. In a population of nearly 190 million, those who took the time to pen a letter to Mrs. Kennedy were clearly exceptional. But the sheer volume of mail, the rapidity with which their messages appeared, the extraordinary diversity of the letter writers, and the parallel manifestations of national grief and mourning evident in the country make the letters a notable element of the public response to the assassination. These individual expressions of grief offer in vivid detail aspects of the widespread reaction to President Kennedy’s death.

For millions of Americans, television provided a focal point for the shock, disbelief, grief, and even fears precipitated by the Kennedy assassination. From the moment CBS interrupted its regular television programming at 1:40 Eastern Standard Time on November 22 to report that shots had been fired at the Presidential motorcade in Dallas, the three major networks provided unprecedented news coverage of the assassination’s aftermath. For four days they suspended their normal broadcasting and advertising in favor of nonstop coverage of the President’s death, lying in state, funeral, and burial. Hungry for stories to fill airtime, the networks ran footage of Kennedy’s life and career in an endless loop along with live coverage of breaking events. Nothing comparable in the history of television had ever taken place. And then, on Sunday morning, millions of viewers witnessed in real time Jack Ruby’s murder of the President’s assassin, as live television covered Lee Harvey Oswald’s transfer from one Dallas jail to another. It was, the New York Times reported, “the first time in 15 years of television around the globe that a real life homicide had occurred in front of live cameras…. The Dallas shooting, easily the most extraordinary moments of TV that a set-owner ever watched, came with such breath-taking suddenness as to beggar description.”

Television captured, as well, the crowds that thronged the Capitol. On November 24, some 300,000 lined the streets to watch as a horse-drawn caisson moved the President’s casket from the White House to the Capitol Rotunda. For the next eighteen hours, hundreds of thousands filed through the Rotunda—some waiting in line in bitter cold for as long as ten hours. On the Monday of Kennedy’s funeral, Tom Wicker would report in the New York Times, “a million people stood in the streets to watch Mr. Kennedy’s last passage. Across the land, millions more—almost the entire population of the country at one time or another—saw the solemn ceremonies on television.” In towns and cities across the nation, and indeed around the world, memorial services, eulogies of all kinds, exhibits, and ceremonies remembering the slain American President continued for months afterward.

Nancy Tuckerman

(standing nearest the window), staff, and

volunteers sort condolence mail in December 1963.

Volunteers opening mail, photograph by Robert Knudsen, John F.

Kennedy Library.

So too did the outpouring of condolence messages. Mrs. Kennedy’s secretaries recruited volunteers to assist in opening, sorting, and acknowledging the correspondence that deluged first the White House and then the Harriman residence in Georgetown where Mrs. Kennedy and her children moved eleven days after the assassination. Some addressed their letters to Hyannis Port where the Kennedys maintained a summer home; the postmaster there estimated on November 30, 1963, that a quarter of a million letters had arrived in the week following the assassination. A few rooms set aside in the Executive Office Building adjacent to the White House soon became the locus of activity, but that space also proved inadequate; additional room was located nearby at the Brookings Institution. The volume of correspondence ultimately exceeded 1.5 million letters. In May 1965, a House Appropriations Committee report noted that Mrs. Kennedy still received 1,500 to 2,000 letters a week, according to the New York Times, “more mail than either former President Harry S. Truman or former President Dwight D. Eisenhower.”

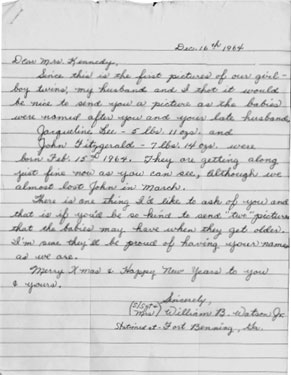

Mrs. William B. Watson Jr. to Mrs. John F. Kennedy, January 16, 1964, Adult Letters, box 18, folder 144, Condolence Mail, John F. Kennedy Library.

Americans also sent artwork, poems, eulogies, Mass cards, newspaper clippings, cartoons, gifts, family Bibles, and military dog tags, among other items, to express their sympathy. Some included snapshots of themselves, their pets, and their children, including the many newborns who had been named after the President or Mrs. Kennedy.

Jaqueline Lee and John

Fitzgerald Watson, twins named after the Kennedys

Photograph of John Fitzgerald Watson and Jacqueline Lee Watson,

reprinted with permission of Mrs. William B. Watson Jr.

A news report that Caroline Kennedy had broken her wrist prompted a letter to the President’s daughter with a picture of the writer’s pet dachshund, sporting a cast on his leg. Some sent to Mrs. Kennedy photographs of the President, which they had taken at campaign rallies and other public appearances. Texan John Titmas enclosed in his condolence letter the two poignant photographs of President and Mrs. Kennedy on this book’s jacket, which he took at Love Field less than an hour before the assassination.

As letters continued to pour in, Jacqueline Kennedy made a brief television appearance seven weeks after the President’s death, in which she thanked the American people for their expressions of sympathy. Mrs. Kennedy’s remarks on January 14, 1964, gave the public their first glimpse of the President’s widow since the state funeral on November 25. Flanked by her brothers-in-law Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Senator Edward Kennedy, and wearing a simple black wool suit, Jacqueline Kennedy spoke for only two minutes and fifteen seconds. She thanked the nation for the “hundreds of thousands of messages…which my children and I have received over the past few weeks.” “The knowledge of the affection in which my husband was held by all of you has sustained me,” she continued, “and the warmth of these tributes is something I shall never forget. Whenever I can bear to, I read them. All his bright light gone from the world.” Noting that “each and every message is to be treasured not only for my children but so that future generations will know how much our country and people of other nations thought of him,” she promised the public that “your letters will be placed with his papers” in the Kennedy Library, then already in the planning stages. Her touching remarks, as well as her assurance that each message would be acknowledged, prompted a new avalanche of condolence letters, with many writers apologizing for their tardiness.

Condolence card, John F. Kennedy Library.

In the ensuing months, Nancy Tuckerman and Pam Turnure, Mrs. Kennedy’s secretaries, oversaw the monumental project of handling the condolence mail. They supervised a cadre of volunteers who responded not only to each letter but also to requests from the writers for Mass cards or photographs of the President, Mrs. Kennedy, or the former First Family. Most correspondents received in reply a black bordered note card with President Kennedy’s coat of arms centered on it, with the simple message: “Mrs. Kennedy is deeply appreciative of your sympathy and grateful for your thoughtfulness.”

Photograph of John F. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Library.

Sorting the mail itself proved to be a task of gargantuan proportions. A consultant hired to advise about a system for handling the letters admitted he was flummoxed. Early in the process famed anthropologist Margaret Mead sent word to Nancy Tuckerman, through a cousin of Tuckerman’s, that an effort should be made to sort letters into categories, given the value the collection would have for future generations of scholars. Despite the additional workload this entailed, Tuckerman complied. Volunteers separated adult letters from children’s, labeled certain items “especially touching,” and created various other subsets such as special “requests.” Two men from Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s staff helped Tuckerman and Turnure create a method of sorting the letters. As late as May 1966, Mrs. Kennedy’s staff was still sifting through and cataloging the condolence letters. “Mrs. Kennedy is reluctant to throw things away,” Pam Turnure reported to the New York Times. “She feels it all came from the heart and who is to know in the future how much any letter or poem or painting will show about how people felt.” Of the task involved in handling the condolence mail, Turnure said: “We are doing all we can so that it will be available for work by scholars.” And yet, for forty-six years, the letters have sat in the Kennedy Library with little sustained scholarly attention.

When the condolence mail was officially deeded over to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston in 1965, it comprised some 1,570 linear feet (that is, the boxes would have extended more than a quarter of a mile if laid end to end). The size of the collection and issues in storage and management posed formidable problems. Eventually these difficulties led the National Archives to pulp all but a representative sample of the condolence mail. The remaining documents represent some 170 linear feet—over 200,000 pages. The team of archivists who sorted through the 830 cartons of general condolence mail saved letters from each major category and created new subsets as they saw fit. All letters offering personal recollections of JFK were retained, as were messages from VIPs, noteworthy mostly for the famous name attached. The enormous volume of foreign mail, some in English but much in the letter writers’ own language, was preserved in large measure, organized by country. “Touching,” “good,” and “representative” letters were also kept—many of them labeled as such by the volunteers who had helped answer the letters. Luckily, the archivists also set aside a random sample of 3 linear feet (approximately 3,000 letters) of the general condolence mail from Americans “as an example of the original inflow of messages to Mrs. Kennedy.”

Photograph of Jacqueline Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Library.

Mrs. Kennedy received very few negative letters. The archivists processing the collection noted an almost “total absence of any letter or comment critical of the president,” although several letter writers objected to the President’s advocacy of civil rights for African Americans and a very few others viewed him as weak in his attempts to combat the spread of Communism. Presumably those who despised the President found venues other than a condolence letter to express their sentiments. It is in the nature of the genre, of course, that praise, warm memories, and generosity toward the deceased predominate in sympathy messages. The assassination itself, to be sure, contributed to a growing hagiography of JFK that began to take shape from the moment of his death. Still, it is well to remember that during his lifetime Kennedy remained among the most consistently popular of Presidents. Only during the final three months of his life, when a growing number of Americans objected especially to his initiation of civil rights legislation, did his approval rating ever slip below 60 percent—and then only to 56 percent. His average approval rating during his Presidency exceeded 70 percent—higher than that of any other modern President.

The political culture then extant in America surely contributed to Kennedy’s idealization. In the early 1960s, the office of the Presidency and the man who held it enjoyed from most Americans a kind of deference that would soon appear a relic of a bygone era. Such fundamental respect and, for some, adulation could flourish, in part, because of a relationship between the President and the press far different from that in contemporary America. An unwritten code of conduct among journalists largely protected John F. Kennedy, as it had previous Presidents, from close scrutiny and publicity about his personal life and, therefore, from scandal. Among the press corps rumors and salacious gossip about Kennedy’s private life abounded, but very little of it ever found its way into mainstream news outlets. Kennedy, of course, had his outspoken critics, and the press aggressively covered the ups and downs of the President, his policies, and his administration. JFK never confronted, however, a press likely to expose details of his private life, medical history, or personal relationships that might have undermined the image he projected. Nor did Kennedy face the twenty-four-hour cable news cycle, with its relentless blend of inquiry, opinion, and commentary, much of it giving free voice to highly partisan critics, which would become a reality for later Presidents.

The deep skepticism, with which both press and public often now view government itself, and political office holders of every level, also was far less apparent in Kennedy’s era. The infamous “credibility gap” that widened through the long, torturous, and costly engagement in Vietnam, bequeathed to and then inexorably widened by President Lyndon Johnson, badly eroded confidence in the Presidency. Determined and repeated efforts to put the best face on the progress of the American engagement in Southeast Asia, despite mounting casualties and growing public concern that the war was unwinnable, in time damaged the faith many placed in the nation’s Chief Executive. That basic trust, buffeted though it often was, reached its nadir in the Watergate scandal during Richard Nixon’s term of office. Brilliant and dogged investigative journalism eventually brought down the Nixon White House and with it, at least for a time, public confidence in the Presidency.

The public’s sense of personal engagement with President Kennedy was also enhanced by extensive press coverage of the youthful, vivacious First Family. Kennedy’s political fortunes soared during the campaign of 1960 in part through his mastery of television. Throughout his time in office, JFK used his facility with this relatively new medium to great advantage. Many letter writers mentioned the utter delight they took in his weekly news conferences—the first to be carried live on radio and television. Kennedy’s self-deprecating humor, dry wit, and ability to spar adroitly and easily with the press captivated many viewers. One such citizen recollected, “my husband & I use to get such a kick out of President Kenedy when the News Reporters used to surround him with questions all he had to do is just open his mouth the Answers just flowed out. He never had to study for a minute.”

Kennedy’s frequent televised appearances clearly entertained some viewers. But he also used the press conferences to explain directly to the American people his policies and intentions, bypassing the interpretive layer imposed by administration officials and political commentators. “Mr. Kennedy taught my children many things on television,” an African American mother from Oakland explained, “because they were interested in him and always wanted to listen to his speeches and my youngest son, Rudolph loved his press conferences and tried to imitate him in many ways.” It’s been estimated that by the second year of Kennedy’s presidency, three out of four adults had seen or heard a Presidential news conference. In 1962, over 90 percent approved of Kennedy’s performance. Jacqueline Kennedy, whose sense of fashion, glamour, and interest in the arts enlivened the Kennedy White House, also attracted much public attention. Her February 1962 televised tour of the White House, showcasing her efforts to restore and preserve the historic mansion, drew three out of four television viewers.

With a newborn and a three-year-old, the Kennedys brought the youngest children to the White House of any Presidential family in the twentieth century. The press covered both Caroline and John F. Kennedy Jr.’s activities as extensively as their parents would permit. Many young parents of the World War II generation, who were busy in the early 1960s raising their own children—the baby boomers—strongly identified with the young White House couple.

New media, the culture of celebrity that they enhanced, and the Kennedys’ considerable personal appeal converged in the early 1960s to make them the most familiar and closely watched of First Families, all of which enhanced the President’s appeal to the American public. Still, JFK’s personal qualities surely created some of the magic. Those letter writers who describe even momentary encounters with President Kennedy—a handshake, a wave, a brief conversation—remembered a warm and engaging man whose enjoyment of politics was palpable, who seemed sincere in his convictions, and who appeared to take delight in meeting them. These realities, of course, deepened the personal anguish many Americans felt after Kennedy’s assassination. There was much, of course, the public did not know until many years after, but those revelations lay in the distant future.

No historian should construct a biography from condolence letters. As Jacqueline Kennedy herself noted shortly after his death, Kennedy was a complex man who would, she predicted, always elude complete understanding. His strengths and weaknesses as a President and as a person will likely remain a subject of study and debate for many years to come. But part of what draws people to that debate is the faith and hope so many Americans of such diverse backgrounds placed in the man, and the loss they felt with his terrible, untimely death. In truth, the condolence letters to Jacqueline Kennedy are less about her husband than they are about those whose hearts he captured and their dreams for their country. As one young man wrote to his sister after the assassination: “His death is disquieting to me beyond reason, perhaps, but the death of an ideal is profoundly worse…. I am incapable of forgetting his words: ‘We must do this not because our laws require it, but BECAUSE IT IS RIGHT.’”

Despite the painstaking care taken to preserve the letters written to Mrs. Kennedy, no academic historian heretofore has systematically read through the entire collection of condolence mail, making it a central focus of sustained study. (The foreign mail constitutes a vast canvas for another historian.) Yet to read this material is to grasp viscerally the enormous impact of Kennedy’s assassination on many Americans. In this book, readers will find roughly 250 letters, most of them written by “ordinary” Americans, all of them selected because they help illuminate how some thoughtful citizens, who took the time to record their thoughts, responded to President Kennedy’s death. These messages, by their very nature, often begin and end similarly with the writer’s wish to offer his or her regret and sympathy.

But through the prism of everyday citizens, the letters included here recount in a very direct and moving way what President Kennedy and his death meant to writers as diverse as the nation. Coal miners, dairy farmers, suburban Republicans, urban blue-collar Democratic Party loyalists, housewives, inmates, schoolchildren, Catholics and Jews, World War II veterans and concentration camp survivors, whites and blacks with powerful responses to Kennedy’s civil rights’ initiatives, were among the letter writers. Their messages constitute a remarkable record, full of personal anguish and revelation as well as profound meditations on grief, loss, and the human condition. They likewise reveal political passions, prejudices, and perspectives on the nation and the Presidency that predate the chaos and disillusionment ushered in by the Vietnam era and Watergate.

The way in which the correspondence reflects the nation’s racial history is alone noteworthy. The early 1960s still belonged to the age of segregation, and there are many letters from African Americans as well as white Southerners that reveal the weight of, as well as the struggle to confront, racial inequality. “We loved your husband because he thought negroes was Gods love and made us like white people and did not make us as dogs,” an African American North Carolinian wrote. “I am colored and poor but clean,” another woman reassured Mrs. Kennedy in extending an invitation to the former First Lady to visit her at her home in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Most of all, the letters tell the story of Americans united across all their many differences in their shock and abhorrence at an event they could scarcely comprehend. “I am a Florida Dairy Farmer who has been a lifelong Republican. I am Protestant and have been anti-Kennedy since 1960,” one man wrote. “However, I feel a desperate urge to extend my deepest sympathy to your children and to you. As an American I am deeply ashamed at the manner in which the President met his end.” Many believed they had lived through an event that would alter history’s trajectory. Noting that “in two seconds history’s course was changed,” a young man observed: “The irrationality of life will never be more clearly set down for us. I grieve for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.”

My own personal recollection of the Kennedy assassination echoes these sentiments. In the fall of 1963, when I was eleven years old, President Kennedy came to my hometown to dedicate the Robert Frost Library at Amherst College. As every local schoolchild knew, Frost had once lived in Amherst, and it was easy to imagine that he had our small town in mind when he wrote about the New England landscape. One such poem was “The Gift Outright,” which Frost had read at President Kennedy’s inauguration. “This land was ours before we were the land’s,” the eighty-six-year-old Frost recited from memory on that bitterly cold January morning that began the administration of the forty-three-year-old President.

John F. Kennedy at Amherst

College, October 26, 1963

John F. Kennedy at Amherst College, photograph by Dick Fish,

Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, by permission of

the Trustees of Amherst College and Dick Fish.

Frost died in January of 1963, and Kennedy’s visit to the groundbreaking ceremony was meant to honor the poet and repay a favor. I vividly recall waking up with a jolt of anticipation on that sunny October day. As I walked the short distance from our home to the college with my best friend, the smell of wood smoke hung in the air. Before long we heard the President’s helicopter whirring overhead. After it made a slow landing on Memorial Field, a motorcade formed, and a pale yellow Lincoln Continental took the President along streets that wound back to the center of the Amherst campus. Kennedy delivered a formal speech inside the “cage,” the college’s outsize athletic building with its dirt floor and hanging nets, but that event required tickets and was reserved for Amherst alumni, dignitaries, and adults—a group I had not a prayer of joining.

Following the formal ceremonies in the cage, Kennedy was to deliver brief remarks outdoors to the large crowd of town residents who thronged the Amherst campus. The college had planned for a turnout of 5,000 but over 10,000 citizens swarmed the grassy hillside. We pushed our way as close to the front as we could, and then saw a shock of his chestnut hair, heard his distinctive voice, and glimpsed the American President.

Less than one month later, Kennedy was dead. Our sixth-grade class was being given a tour of the school library on November 22 when I heard some staff members saying that there had been a shooting in Dallas and that the President had been wounded. Just that morning my parents had discussed over the newspapers the climate of right-wing extremism that was expected to greet Kennedy during his visit to Texas. I didn’t understand the issues, of course, but grasped enough that when I heard the President had been shot, I instantly believed it. I came home after an early dismissal to find my parents staring at the television set as they would until late Monday evening.

My father, especially, was deeply distraught. Born, like Kennedy, in 1917, an Irish Catholic native of Massachusetts, and a naval officer during the Second World War who had served in both the European and Pacific theaters, he much admired Kennedy. On November 22, he told my mother that he felt as if he had lost his own brother. Certainly, the expression of gravity, worry, even devastation on my father’s face was one I had never before seen. I understood that something of tremendous moment had occurred. And with this rapid convergence of events—the Presidential visit, the assassination, and my father’s evident distress—came for me an acute understanding of how quickly a lived present could recede into the past. These events, without question, shaped my decision to become a historian.

What follows,

then, provides an illuminating snapshot of the United States as it

existed in 1963 and a rare opportunity to discern how some

Americans made sense of a cataclysmic historical

event that lingers in our national memory. The political conflict

and social ferment that many writers address mirrors persistent

tensions in contemporary American society. There was, to be sure,

nothing ordinary about the events that inspired Americans to take

stock of their own life experience, the fate of their country, and

the tragic death of their “beloved President” in November of 1963.

“The coffin was very small,” as one sixteen-year-old girl observed,

“to contain so much of so many Americans.” In reflecting on their

sense of loss, their fears, and their striving, the authors of

these letters wrote an American elegy as poignant and compelling as

their shattered and cherished dreams.