THE DOORBELL RANG, AND Mrs. George Darling sighed. She had just sat down for her first relaxing moment after a long and busy day. She put down the newspaper—another awful story about somebody disappearing in the Underground—and rose from her chair.

“Who is it?” shouted a high-pitched voice from upstairs, followed by a clatter of descending footsteps, followed by the appearance of her two sons, John and Michael.

“Who is it?” repeated Michael, who was three and, as always, was holding his stuffed bear.

“How would she know?” said John, who was seven and therefore knew a great deal more than Michael about everything. “She hasn’t opened the door yet, you ninny.”

“Mum!” cried Michael. “John called me a—”

“I heard what he called you,” said Mrs. Darling, glaring at John as she reached the front door, “and I will discuss it with him later. But right now you will both behave.” She opened the door, and her frown turned instantly to a smile at the sight of the tall figure standing there.

“James!” she said. “What a wonderful surprise! Do come in!”

“Are you sure?” James said. “I know it’s late, but…”

“Nonsense!” she said, taking his arm and pulling him into the foyer. “John, Michael,” she said. “This is Mr. Smith.”

Michael eyed James warily. “Who are you?” he said.

“Michael Darling, that is a rude question,” said Mrs. Darling. “Mr. Smith is a very dear friend to your father and me. And we are delighted to see him at any hour, especially after…James, how long has it been?”

“Years, I’m afraid, Molly,” said James.

“Molly?” said John. He giggled.

She turned to her son. “It’s the name I went by when I was a girl.”

James blushed. “I’m sorry!” he said. “I didn’t realize …”

“There’s no need to apologize,” said Molly. “It’s just that George considers Molly a childish nickname. These days he prefers to call me by my given name, Mary. But that would sound odd coming from you. Please, call me Molly.”

“Molly!” said John, giggling again.

“Are you a barrister?” asked Michael. “Our father is a barrister. He wears a wig. But he’s not a lady.”

“Michael!” said Molly.

“Well, are you a barrister?” repeated Michael.

“No,” said James, with a glance toward Molly. “I work for Scotland Yard.” He saluted the boys. “Inspector Smith, at your service.”

“An inspector from Scotland Yard!” said John, delighted. He peered up at James through his round eyeglasses. “Are you looking for a murderer?” he said.

James grinned. “Not at the moment, no. But I am on a top secret assignment.”

“Really!” said John.

“Yes. I’m looking for children who skip their baths.”

“Oh,” said John, disappointed.

“I’ve had my bath!” said Michael. “Yesterday, I think.”

James was about to say something more when a third child descended the stairs—a girl of eleven, with long brown hair and a face that might be called delicate, except for the boldness in her startlingly green eyes.

“My goodness,” said James. “Is that…”

“Yes,” said Molly. “That’s Wendy. I imagine she was just a baby when you saw her last. Wendy, this is Mr. Smith.”

“How do you do?” said Wendy, offering a curtsy.

“Please forgive my staring,” said James. “But you look so much like your mother when I first met her.”

“What was she like?” said Wendy, with a disarmingly frank look that James had seen many times on her mother’s face. “Was she an obedient child?”

“Obedient?” said James, barely stifling a laugh.

“Wendy!” said Molly. “Mr. Smith did not come here to discuss my childhood behavior. Now, you three go upstairs. Wendy, please put your brothers to bed, and then yourself. I’ll be up to tuck everyone in after Mr. Smith and I have talked.”

Reluctantly, the children obeyed. James, watching them climb the stairs, said, “They’re fine children, Molly. I can see you in Wendy, and George in the boys.”

“And mischief in all three,” sighed Molly.

“And how is George?” said James.

“He’s doing well,” said Molly. “Very busy with his career. He’s at some sort of dreadful law banquet tonight, as he often is.” She paused. “But you didn’t come to ask about George, did you, James?”

“No,” admitted James, giving Molly a somber look. “Something’s come up.”

“I’ll make tea,” said Molly.

A few minutes later they were in the sitting room, cups in hand. James took a sip, swallowed, and began.

“Are you familiar with Baron von Schatten?”

Molly frowned. “The German? Yes. George and I saw him briefly at an embassy dinner. Odd man. Wearing darkened glasses, indoors? And at night?”

“The glasses are far from the only odd thing about him,” said James.

“What do you mean?”

“Molly, this is a man who, only a few years ago, had no connection whatsoever with the royal family. He appeared as if from nowhere, and somehow managed to ingratiate himself with Prince Albert Edward. The prince’s staff and advisers were wary of von Schatten, of course, but the prince seemed oddly tolerant of him. Almost deferential.”

James took another sip of tea.

“Then, one by one,” he continued, “those same staff and advisers suffered misfortunes—illnesses, injuries, even two deaths. All of these incidents appeared to be either natural or purely accidental. But each one removed another barrier between von Schatten and the prince, so that when the prince became king, von Schatten was his most trusted—in fact his only—adviser. It is now almost impossible for anyone else, including his family, to get close to him. For all intents and purposes, von Schatten is, next to the king, the most powerful man in England.”

“I had no idea,” said Molly.

“Very few people do,” said James.

“How do you know all this?” said Molly.

“Six months ago,” said James, “I was given an unusual assignment: to take a menial position on the palace staff, without revealing my identity as an inspector. My instructions were to find out as much as I could about von Schatten and his relationship to the king.”

“Spying on the king?” said Molly.

“I questioned it myself,” said James. “But Chief Superintendent Blake told me that the orders came from the highest levels of government. They’re worried about von Schatten’s influence, Molly. Very worried. And they have good reason to be.”

“What do you mean?”

James, leaning forward, lowered his voice. “Molly,” he said, “do you know what von Schatten’s profession was, before he came to England?”

Molly shook her head.

“He was an archaeologist,” said James. “Quite a well-known one, in fact. But his career ended suddenly ten years ago, when he had a serious accident. It’s the reason he must always wear those dark glasses. Or so he says.”

“What sort of accident?”

“Von Schatten is vague about the details,” said James. “But it happened at an archaeological site in the North African desert. Von Schatten was exploring the ruins of a temple—a temple that had stood for thousands of years, only to collapse twenty-three years ago in a mysterious explosion.”

Molly went pale. “Rundoon,” she whispered.

“Yes,” said James. “Rundoon. Von Schatten was exploring the Jackal.”

“But it was destroyed!” said Molly. “The rocket…”

“The temple was severely damaged, yes,” said James. “Obliterated, in fact, aboveground. But there was a crater, and at the bottom of that crater a hole, a sort of cave in the sand. Von Schatten went down there. He went alone—the guides would not go within a mile of that cursed place. He was gone for several days. When he finally came out, he claimed to have fallen and hit his head and lost consciousness for a time. He had no visible injuries. But he was…changed.”

“How so?” said Molly.

“For one thing, he could no longer stand sunlight. That can happen temporarily, of course, after days in total darkness. But the affliction stayed with von Schatten. He is never seen outside, and his eyes are always hidden behind those impenetrably dark glasses. But there was more: his personality had changed. Before, he had been outgoing; now he was reserved, sullen—an utterly different person. His family, his colleagues, said it was as if”—James lowered his voice—“as if someone else were inhabiting his body.”

For a moment, the two just stared at each other. Then Molly shook her head.

“It can’t be,” she said, her own voice a whisper. “After all this time…It just can’t be.”

“I wish you were right,” said James. “But after what I learned at the palace …”

He leaned forward, his eyes boring into Molly’s.

“Molly,” he said. “I think it’s him.”

“And that,” said Wendy, “is why the moon changes its shape.”

“Because an elephant is eating it?” scoffed John. “That’s silly!”

“I’m sorry, but that’s your bedtime story,” said Wendy, rising from the rocking chair at the end of the boys’ beds.

“That’s the worst bedtime story ever,” said John.

“Well, it’s the one you get tonight,” said Wendy. It was true; she usually told a much longer story. But tonight she was more interested in what was going on downstairs.

“How does the moon come back?” said Michael.

“I don’t know, said Wendy impatiently. “Perhaps the elephant spits it back out.”

“But then it wouldn’t be round!” said John. “There would be just pieces of moon, covered with elephant spit.”

“Good night,” said Wendy, going to the bedroom door.

“But what does the elephant stand on?” said Michael.

“I said good night,” said Wendy, closing the door behind her, leaving the two boys to complain to each other about the declining quality of bedtime stories.

Wendy walked to her own bedroom, paused, then continued down the hallway to the top of the stairs. She listened for a moment, then descended on quiet bare feet to the staircase landing. Now she could hear her mother and Mr. Smith talking. She couldn’t make out the words, but her mother’s tone was clear: she was upset about something.

Wendy frowned. Her mother was not easily upset. What was this mysterious Mr. Smith telling her? What had brought him here at this hour?

On tiptoe, Wendy started down the stairs.

Molly was shaking her head. “I thought this was over,” she said.

“We all did,” said James.

“After Rundoon,” said Molly, “when years and years passed, and there were no more starstuff falls…Father was convinced—all the Starcatchers were—that the Others had finally been defeated, along with that awful creature …” She stopped, not wanting to say the name.

“Ombra,” said James.

Molly flinched, remembering the dark, shifting shape that caused her and her family so much torment and terror. “Yes,” she whispered. “Ombra.”

“But what if he survived?” said James.

“No,” said Molly. “He was on the rocket. It was destroyed in the explosion.”

“Yes. But remember that Peter escaped that rocket. And so did his shadow. Perhaps Ombra did, too, somehow.”

“And you think he now controls von Schatten? That he has taken his shadow?”

“No,” said James. “That’s the curious thing. Von Schatten casts a shadow.”

“But wasn’t that how Ombra controlled people? By taking their shadows?”

“It was,” said James. “He did it to me, once.” James shuddered at the memory. “But this is something different. I think something happened to Ombra in the explosion, something that weakened him, left him unable to function on his own. I think he stayed down there, deep in the hole in the sand, in the dark, waiting. And when von Schatten came along, Ombra somehow…inhabited him, and now controls him.”

“But how can you know that?”

“I watched him in the palace, Molly. I got close to him only once; he keeps the palace staff at a distance, dealing with them through his assistant, an unpleasant man named Simon Revile. But I was able to observe von Schatten from a distance a number of times. He is always close to the king, and makes physical contact with him often.”

“He touches the king?”

“It’s very subtle—an elbow brushing an elbow, a hand resting for a moment on a shoulder. But once you know to look for it, you see it often. And each time, the king responds. Again, it’s subtle—a flutter of the eyelids, a slight twitch of the head. But it’s there, Molly; it’s definitely there. I think this contact is how Ombra, through von Schatten, is controlling the king.”

Molly shook her head. “I’m sorry, James,” she said. “But this is simply too far-fetched. Perhaps something did happen to von Schatten in Rundoon. Perhaps he has a strange relationship with the king. But to say that he’s being inhabited by that creature—how can you possibly know that?”

James leaned toward Molly, and when he spoke, his tone was urgent.

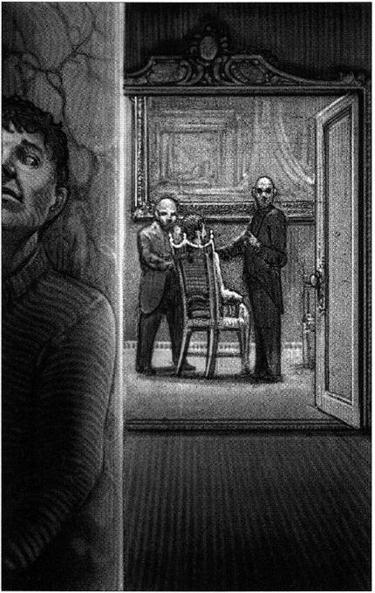

“I told you that on one occasion I managed to get close. I won’t go into the details of how I did it, save to say I’m fairly skilled at picking locks. And late one night, through some luck and some lying, I managed to get to the hallway outside the king’s bedchamber. The door was open and the hallway was dim; if I stood in the right place, I was able, without being seen myself, to observe the king, von Schatten, and Revile, and to overhear some of their conversation. Von Schatten did most of the talking, and he seemed to be talking to Revile—almost as if the king weren’t there.”

“Talking about what?”

“The king’s coronation,” said James. “Von Schatten was very concerned about the date. He stressed several times that they needed to have something ready for the coronation. Then he talked about something else, and I didn’t follow most of it, but it had something to do with Belgium, and the missing piece.”

“The missing piece of what?”

“I don’t know—only that von Schatten wants it found soon. He was speaking softly, and I was missing some of the words, so I decided to try to move a little closer. And that was when it happened.”

“What happened?”

“He felt me, Molly.”

“What?”

“He felt my presence. And…and I felt his. It was Ombra.”

“But how can you be certain?”

“Molly, Ombra took my shadow once; he controlled me. I shall never, as long as I live, forget that horrible feeling, the cold filling my body, and this…this unspeakable evil filling my mind. This was the same sensation, Molly. And the worst of it was that as I sensed him, he sensed me. He knew exactly who I was. I’m sure of it. He stopped talking immediately and walked quickly toward the doorway.”

“What did you do?”

“I ran. I admit it, Molly: I was terrified. I ran down the hallway and kept running until I was out of the palace. I felt such a coward. But I couldn’t help myself.…It was as if I were a boy again, a frightened little boy.”

“I don’t blame you at all,” said Molly, remembering her own experiences fleeing from the dark shape. “But what did you do then?”

“I went back to the Yard, first thing the next day,” said James. “My intention was to report to my superiors.” He smiled ruefully. “That did not go at all well.”

“What happened?”

“Molly, think about it. They’re police officers; they live in the world of crime and criminals. Of fact, and evidence. They know nothing about starstuff, or the Starcatchers, or the Others, or Ombra. When I tried to suggest to them that von Schatten was no ordinary man, that he was influenced by something evil, something inhuman, they looked at me as if I were a madman, or a child telling ghost stories. They don’t believe me, Molly. They would never believe me. I’m facing disciplinary action simply for having brought this up.”

“Oh dear,” said Molly. “How awful.”

James waved his hand. “My career at Scotland Yard doesn’t matter. This is far more important than that. Whatever von Schatten—or Ombra—intends to do, he must be stopped, Molly. And only the Starcatchers can stop him.”

“James, the few Starcatchers who are left are old and feeble.”

“But your father …”

“My father is very ill, James. He is in no condition, mentally or physically, to cope with something like this.”

“But there must be somebody,” said James.

Molly shook her head. “When the starstuff falls stopped, the group you knew as the Starcatchers gradually ceased to exist. Essentially there are no Starcatchers anymore, James.”

James studied her for a moment, then softly said, “There’s you, Molly.”

Molly shook her head. “I’m not a Starcatcher anymore, James. I’m a mother of three and the wife of a prominent barrister who does not approve of talk of starstuff and evil creatures and the like. Childhood fantasies, he calls them.”

“But they were real, Molly. Surely George knows that. He was there, at Stonehenge, in Rundoon. …”

“Yes,” said Molly. “He was there. But he is determined that we put that part of our lives behind us.”

“We can’t, Molly. It has come back. We must confront it.”

Again, Molly shook her head.

“I don’t think so, James,” she said. “I know you believe you felt something in the palace, but what if you were mistaken? I can’t just give up the life I’ve been leading all these years to chase after something you might have imagined.”

“I didn’t imagine it, Molly.”

Molly looked down. “I’m sorry, James,” she said. “I can’t.”

James stared at her for a moment, then said, “I can’t believe that Molly Aster would say such a thing.”

Molly looked up and met James’s gaze. “I’m not Molly Aster anymore,” she said. “I’m Mrs. George Darling.”

James looked at her for a few moments, then nodded.

“All right,” he said. “Then I’ll ask a favor of you.”

“Of course.”

“Just think about what I’ve told you tonight. Perhaps something will occur to you—someone else I could go to, someone who might be able to help.”

“But I don’t—”

“Please, Molly. I’ve nobody else to turn to. The coronation date is approaching. And I fear that von Schatten, now that he knows who I am, will use his position against me. Just give it one day of thought, Molly.”

“All right,” said Molly reluctantly. “I promise I’ll think about it.”

“Thank you,” said James, rising. “I’ll come back tomorrow evening for your answer, if that would be all right.”

“All right,” said Molly, remembering that her husband had yet another social function the next evening. As she walked James to the door, she said, “Do you need a taxicab?”

“No,” said James, “I’ll take the Underground.”

“Do be careful, then,” she said. “Those awful disappearances …”

“Oh, I’ll be fine,” said James.

He turned and gave her hand a squeeze. “It’s good to see you again, Molly.”

“And you, James. Do you ever see the others? Prentiss? Thomas? Ted?”

“We get together from time to time,” said James.

“They’re all doing quite well. Ted, if you can believe it, is a fellow at Cambridge. Dr. Theodore Pratt.”

“Good for Ted,” she said. “Give them all my best.”

“I will,” said James. He hesitated, then said, “Do you ever think about…Peter?”

Molly blushed. “Sometimes,” she said. “And you?”

“Quite often,” he said. “I find myself wondering if I’ll ever see him again.”

“I don’t know,” said Molly slowly, “if that would be such a good thing, after all these years.”

James looked at her for a moment, then said, “Well, good night, then, Molly. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Yes,” said Molly. “Tomorrow.”

James opened the door and stepped out into the fog-darkened London night; in a moment he was gone. Molly closed the door and stood looking at it, her mind swirling with troubled thoughts. She jumped at the sound of a footstep behind her.

“Wendy!” she said, turning to see her daughter at the base of the stairs. “What are you doing down here? Why aren’t you in bed?”

Wendy responded with questions of her own.

“Mother,” she said, “what is a Starcatcher?” She stepped forward, her green-eyed gaze fixed on her mother’s face.

“And who is Peter?”