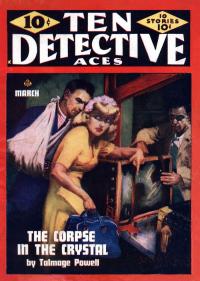

Talmage Powell

The Corpse in the Crystal

Chapter I

By the time Abner Murder and I got on the death wagon, the kill fest was going strong and showing no sign of stopping. Every one of the deaths indicated that the grim reaper had gone on a whimsical spree — except that death is never whimsical.

Murder and I had no idea we would become involved in the affair. Subsequent investigation showed those initial deaths happened something like this:

We’ll take Frank Snow first, though no one is sure even now which victim received the first note. Snow was in the same business as the chief and I; he was a private detective.

We weren’t proud of that fact and didn’t regard him as an ethical member of the profession. Snow was the sort of slim, sleek man who didn’t care particularly how he made his dimes. A little blackmail in the course of regular business he regarded as a natural by-product of the operation of a private detective agency.

His secretary was at the courthouse that morning, looking up a trial in the court records that Snow was interested in. He was alone in his fifteenth floor office as he began opening his morning mail. He was tranquil, with a deep sense of well-being at the moment he opened the thin white envelope. He read the contents, and a slow frown furrowed his brow. He crushed out his cigarette abruptly, read the note again:

Mr. Snow.

I am the owner of the only truly authentic crystal, blessed by the lamas of Tibet, on the face of the earth. Though I am an utter stranger to you, I feel it my duty to warn you that I have seen your death in the crystal. You will die of drowning, Mr. Snow, before noon today. Nothing can stop it; no power can save you. The crystal never lies!

Frank Snow muttered, “The damndest crackpot note I’ve ever seen! Die by drowning before noon today!”

His laugh was hard, sure. He’d never heard of anything more ridiculous. He was alone, fifteen sheer stories above the street. The only water near him was in the decanter in the outer office. With an abrupt movement, his face mirroring a sense of high comedy, Frank Snow rose from his desk, crossed the office, and locked the door. No one, he was positive, could come through that door. He was quite alone, and he did not intend to leave this office until lunchtime, at one-thirty.

He laughed, crushed the note from the crackpot, Nostra, in his hands and threw it in the trash basket.

His blonde secretary finished her errand and returned to the office at eleven forty-five. Without removing her hat and coat, she hurried across the outer office to deliver the transcription of the court record to Frank Snow. She found his private office locked. She called his name. There was no answer. She waited, called his name again. She deliberated a few minutes, then called the superintendent of the building. The old janitor came up five minutes later.

“Mr. Snow is in his private office, locked in,” she told him. “He doesn’t answer. I want you to use your passkey on the door.”

“But, Miss, he might be—”

“I’ll accept responsibility if he blesses us out,” she said. She added emphatically, “He wanted this court record. A man is either sick or drunk when he wants something and doesn’t answer to his name!”

So the janitor unlocked the door. Frank Snow was neither sick nor drunk. He was lying in the middle of his office, dead. An hour later the medical examiner hesitantly rendered his astounding verdict. Death by drowning — with the victim sealed in the fifteenth floor office of a modern building with not a drop of water near him...

Loren “The Lion” Cole strode his swank office on the twentieth floor of the same building in which Frank Snow ran a detective agency. However, Loren Cole knew nothing of Frank Snow. Had never heard of him, in fact. Had he been told of Snow’s existence, he would have considered the imparting of the knowledge as so much wasted breath by the teller. It mattered not in the least that Frank Snow was dying five floors beneath him at that very moment. The Lion was upset. Some fool had written him a note, signing it, Nostra, Possessor of the Crystal.

The Lion stared at the paper again as he paced the inner sanctum that was his private office, from which grew a thousand tentacles of power belonging to an oil king worth eleven million dollars. The Lion roared a curse, read the note again:

Mr. Cole:

The only true crystal on the face of the earth tells me that you will die from an accident with an automobile, resulting in a broken neck, before noon today. Though you and I were total strangers until the crystal revealed your name, I know it is my duty to tell you that the crystal never lies!

“A pack of rats,” three of Cole’s battery of secretaries in the huge outer office reported him as roaring. “A pack of rats, sending a note like this, trying to get a man so upset they can best him in business!”

That’s the way he translated the note. A prank from a business rival who was dabbling in the application of a queer, negative psychology.

The Lion jerked open the teakwood door he’d imported when he first set up this suite of offices ten years ago. “I’m seeing no one,” he roared. Two secretaries swallowed their gum quite involuntarily.

The whole office force of a dozen people later swore that no one had entered that sanctified office. All twelve couIdn’t have been lying. The Lion was alone in that twentieth floor office until one of the secretaries tapped timidly on the teakwood door, a sheaf of letters in her hand that just had to be signed.

The usual roar did not greet her. Frowning, she took her courage in hand and eased the door open a crack. Her scream silenced every clattering typewriter. Twelve people were suddenly jammed in the door, staring at Loren “The Lion” Cole.

He was sprawled in the middle of his office, his neck twisted at a gruesome, grotesque angle. Clearly it was broken, and the Lion had died without a roar. The hands of the clock on his desk moved to twelve o’clock, noon. On the floor near the Lion’s foot was a little, red plastic toy automobile. It belonged to his son, who must have left it after a visit with his mother, forgotten. Such a ridiculous little thing for a man to trip on and break his neck...

Across the city Gregory Sloan gazed at the top of his desk. It was a magnificent desk, oval in shape, made of the finest walnut. But Gregory Sloan was not interested in magnificence at the moment. He was short, heavy, bald, with a greasy look about him, and a nose that looked as if it had been pushed up into his face from its base, making the nostrils prominent. He knew he resembled a fat pig more than any other creature, but even that did not bother him at present. The devil’s own share of worries was on his shoulders.

He had sunk every dime he owned in this place, his Forty Nine Club. Everything had been set for Gregory Sloan; then the fool voters of the city had changed things at the last election. Gregory Sloan’s man had been voted out. All his carefully laid plans had gone to the well-known pot.

The gambling rooms cm the floor below were closed. Gregory Sloan had, in fact, narrowly missed having the Forty Nine Club dice in the office of the D. A. at this very moment. Then that fool girl who’d got drunk and committed suicide. Bad publicity, cops hounding him.

Every dime he owned tied up in the spacious, luxurious club that, in its entirety, occupied the two floors below him. A club that would not pay its own way without the gambling rooms and the sucker traps. He was going broke. There was nothing he could do to stop it. The City knew he was going broke, watching him and laughing. It was hell to come up the ladder from small-time punk and gunman to the crest, then lose it all.

With a grunting, heavy sigh, he turned his mind from his money problems to the maddening, crank note before him; the note that had arrived in his morning mail three hours ago.

Gregory Sloan had neither Frank Snow’s cold brutality nor Loren Cole’s blustering courage. Gregory Sloan found that the implications of that note had been growing in his mind since he’d first read it and tried to shrug it off. He found the note crowding everything else from his mind.

Mr. Sloan:

Though I have never had the pleasure of meeting you, I feel that I should warn you that my crystal, blessed by the lamas of Tibet, has foretold your death. You will die of poisoning before two o’clock this afternoon. Whether or not you eat or drink, it will make no difference. The crystal never lies!

Gregory Sloan grunted a curse. Poison — before another thirty minutes had passed, for it was now one-thirty. The devil take this fool Nostra! It was impossible, for Gregory Sloan had not been out of his office since he’d received that note. He did not intend to go out of it. Furthermore neither did he intend to touch anything that might conceivably contain poison. Death was one way out of his financial dilemma, but Gregory Sloan did not welcome that avenue of escape.

He crushed the note in his thick fingers. Few people, those few only the most trusted, even knew of the exact location of this office. Gregory Sloan was well hidden, quite alone, and he’d touched nothing that might poison him.

Yet even as the thought was going through his mind, he felt his stomach begin to burn. Eyes staring, he clutched the edge of his desk, hauled himself erect. It was exactly one-thirty. Even a slow-acting poison might do its work in the space of half an hour.

Gregory Sloan tried to cry out against the impossibility of it. It couldn’t happen — yet he fell to the floor, his body twisting, jerking in the sort of convulsion that came from the administration of strychnine...

So that’s the way things stood be-fore Abner Murder and I got our feet to the mess. We read the scare headlines, of course. As far as we could see the case would never concern us. Until the little pocket arrived from Frank Snow in the afternoon mail.

I was going through some old records while the chief sat at his battered desk, his baby-pink, Santa Glaus face lighted while he devoured cream puffs and read a magazine.

The lanky mailman came in, screwed up his eyes at Murder. The mailman had never quite reconciled himself to the fact that the dimpled, dumpy, mild, blue-eyed, little guy at the battered desk had a monicker like Murder. The mailman deposited a bundle of. mail on my desk. The first thing I noticed was the manila envelope with Frank Snow’s return address. The mailman closed the door behind him, and I picked up the envelope.

I was on the point of opening it, when the door opened again and two men came in. I knew them both by sight and police record. It only took one glance for me to reach around where my shoulder rig and thirty-eight were hanging on the back of my chair. They were that kind of lads. The short one was Rick Duvarti. The tall yegg was a bloody hophead named Burt Krile.

I didn’t get my gun. Krile had a flat automatic in his own fist. He slammed it across the back of my hand. Duvarti stood in the middle of the office, covering his pal with a wicked looking thirty-eight on a forty-five frame.

I sat very easy-like and the chief laid aside his magazine. “What is this, boys?”

“Just a sociable little call,” Duvarti said. “We been watching the mailman. He just came out of this office. We want something left here.”

Burt Krile’s eyes lighted as his gaze swept my desk. He matched the envelope with Frank Snow’s return address. “I got it, Duvarti,” Krile said with a nasty laugh that came from the bottom of his beanpole frame. Krile crammed the envelope in his coat pocket.

I knew Abner Murder would suddenly trade his eye teeth for a look at the contents of that envelope. He said, “That’s a Federal offense, Krile.”

Duvarti, short, squat, chuckled. “You wouldn’t go yelling for the Feds, would you, Murder? Later on, it might go hard with you and this Luke Jordan ape.”

I don’t like being called an ape. But there was nothing I could do about it. With another short laugh, Krile struck with his automatic like a viper. I tried to duck, but he was fast. Duvarti, I saw out of the corner of my eye, looked awful unsteady on the trigger.

My head exploded against the fiat of Krile’s gun. I felt myself falling, saw in a haze the chief trying to get to the gun in his desk drawer. Duvarti said something in a nasty tone. Krile moved fast. His automatic lashed again, right on the crown of Murder’s sandy head. Then I quietly went to sleep.

I blinked my eyes open with the chief slapping my cheeks. I sat up; the chief said, “As the strongarm half of this detective agency, Jordan, you’re a bust.”

“Nuts,” I said. “I didn’t notice you thinking your way out.” I got to my feet, nursed my head with my hand. “What did our playmates take?”

“Nothing,” Murder said, “but the letter. They conked as to give them plenty of time to make a getaway, not to have time to search the office. Finish the mail, Luke, something tells me this climate is unhealthy for two boys named Duvarti and Krile.”

He checked his gun while I ripped through a few letters. Then I handed him a square sheet of paper. I watched his face while he read:

Mr. Murder,

I have seen death in the crystal. Your death. Though it is the middle of August and the thermometer at the moment stands at ninety-nine degrees, the crystal states that you will freeze to death before noon tomorrow! The crystal never lies!

Nostra, Possessor of the Crystal

Murder folded the paper very neatly in his pudgy fingers. “It looks,” he said, “like we’re into something!”

Chapter II

Tim Brogardus was a headquarters dick with more brawn and vociferous lung power than brains. He motioned us to chairs when Murder and I entered his office. Tim had a harried expression on his face, a pile of filing folders on his desk, along with an afternoon paper. He was speaking into the interoffice phone with obvious control.

“Sure, Chief. Of course I’m doing everything I can! You’ve had a call from the mayor, and scared citizens are flooding the switchboard? Yes, sir! Of course — just give me a little time!” He slammed the phone down and passed hi# hand over his brow.

“I see,” Murder said, “that the crystal-gazing Nostra has upset our fair city.”

“That ain’t the word for it,” Brogardus said. “The whole damn town is afraid to go to sleep or sit down in an empty room. Those reporters—” He gritted his teeth audibly, looking at the headlines on the desk before him.

Tim’s jaw dropped as Murder shoved the little square of paper he’d received from Nostra on Tim’s desk. Tim read the note three times. “So you’re going to freeze to death in the middle of August!”

“That’s what the man says,” Murder said. “So if you’ve learned anything about this Nostra, or located him—”

“Located him!” Brogardus howled. “Listen. The guy is back in a cell right now! He walked up to a cop last night and said he wanted to be arrested. The cop laughed it off, told the guy to be on his way. Then this Nostra hauls off and slugs the cop and we tow him in.”

“So he’s been in jail since last night?”

“That’s right,” Tim nodded. “You know what I think? I think he’s trying to alibi himself.”

I expected a cutting bit of sarcasm from Murder at this obvious revelation to which Tim had struggled. But the chief had left his humor back in the office. He said, “Can I see this Nostra?”

Tim looked at the note Murder had received. He shoved bade bis chair. “Come on.”

They’d taken Nostra out of his cell to a little windowless room downstairs. The room was full of smoke when we entered, dark in the corners, with a dozen shadowy men moving like phantoms through the ocean of smoke. They were grouped about the man who sat beneath the glaring, green-shaded light in the middle of the room.

He didn’t look like I’d thought he would. He wasn’t greasy or sinister. Nostra was elderly, grey tinting his hair, with a thin face and a thinner smile. Brogardus, the chief, and I slipped inside the room, listened for a moment to the questions the dozen headquarters men were hammering at the crystal-gazer.

“Who told you to send those notes?”

“No one. I saw it in the crystal.”

“Don’t give us that This crystal business is a phony, a fake.”

Nostra shrugged the remark off.

“How long have you known Loren Cole, Frank Snow, and Gregory Sloan?”

“I’ve told you dozens of times, gentlemen, that I don’t know any of them. Can I have a drink of water?” He half rose; a strong hand pushed him back.

“Listen, you crystal-gazing rat this is murder! You think we’re going to let you go around killing people and get away with it?”

Nostra’s smile was thin. “How could f kill anyone? I was in jail. How could anyone kill those men? From what you have told me, they were all is sealed rooms. It was impossible for them to die.”

“But you said they were going to die!”

Nostra made a weary gesture with his hand. “Precisely. I knew, gentlemen, that I would be branded a fake. I knew I would be under suspicion. I foretold the deaths, and from the generosity of my heart warned the victims. A lesser man, to protect his own skin, would have remained silent. But I knew the risk I was running from the hands of the police when death was an established fact. I accepted it.”

“Bah!” That was Tim. He strode forward, Murder’s note in his hand.

“Did you write this?” Tim bellowed.

Nostra looked at the note. “I wrote it and dropped it in a comer mailbox late last night before I — er — punched the policeman.”

Murder stepped forward. “And you think I’m going to freeze to death in the middle of August?”

You could have heard a pin drop. Very slowly, Nostra looked from the chief’s face down to his feet. Then he raised his eyes once more; his gaze locked with Murder’s. Nostra looked cool and distant even under that hot light, but you could smell sweat in the tight room.

“You’re Abner Murder?”

“I am.”

“Then you will die. Exactly as the note said.”

Somebody shifted his feet. Everybody here, except Nostra, knew the chief, had seen him in action. Murder forced a ghost of a smile. “But suppose I don’t care to die. Suppose I have them lock me in jail until after the time limit tomorrow?”

“You would die anyway,” whispered Nostra. There was a note of finality hanging in his words. There was nothing more to be said.

Back in Brogardus’s office, Tim said, “Murder, we’ve fought and scratched, you and me, and we’ve even worked together on a few cases. Don’t let this get you down. I’ll break Nostra if it’s the last thing I do.”

“I’m afraid you won’t,” Murder said. “He’s got a simple story and he’s the sort of man to stick to it. He was in jail. That’s his alibi and you’re stuck with it. I think you’ve got as much out of him as you’ll get, Tim.”

Brogardus sat down with the air of a man who couldn’t think of anything else to do. He chewed his nails. The chief said, “You might as well give me the low-down, Tim. If I’m going to freeze to death by noon tomorrow...” His smile was wry as he left the sentence unfinished.

“All right,” Tim said, “here it is. Like the paper said, Frank Snow was discovered in his office, drowned. The door was locked, and no water was near him. Ergo, an impossible death.”

Brogardus made a steeple of his fingers. “It may be that somebody had it in for Snow. You Know yourself, Ab, how he was putting his nose in blackmail corners. But if anyone hated him enough to kill him. or feared him that much, it would have been impossible to kill him in the manner that he was.”

“And Loren Cole?”

“About the same,” Brogardus shrugged. “From all appearances, he tripped on a toy automobile on the floor of his office and broke his neck. We’ve talked to his wife and a few business associates. Cole has shown intense worry in the last few days but his wife states that he often had those moods. Several people he had bested in business one way or another hated him. But again, no one was in that office except Cole.”

“That leaves Gregory Sloan, the nightclub owner,” I said. “The paper didn’t have much to say about him.”

“We didn’t give out much,” Tim countered. “Gregory Sloan was a little luckier than the others. His secretary went in his office, found him in a convulsion. She saw the note from Nostra on his desk, mentioning poison.

“She was a quick-thinking gal. She grabbed a glass of lukewarm water and some baking soda from Sloan’s desk, poured it down him. She got an ambulance in a hurry, and they went to work with a stomach pump. Sloan’s in City Hospital now, but we are keeping it under cover that he’s okay. We don’t want another crack taken at Sloan.”

The chief edged forward in his chair. “Then you’ve talked to Sloan!”

Tim cocked an eye at him. “Sure, and that’s the most impossible part of the whole thing. If either Snow or Cole had lived to talk, they might have told us something. Like you, Ab, I was on pins and needles, thinking that in Sloan’s case a slip had been made and we’d get a lead. But he swears that he was absolutely alone from the moment he received the note until his secretary walked in and found him. He touched nothing that might poison him.

“Living, Sloan’s made the puzzle of the administration of the poison bigger than ever. He swears there was no way anyone could have poisoned him — unless he was slipped a capsule late yesterday or early this morning. At breakfast, say. But he’d have noticed a capsule, so that’s out.”

Tim flung up his arms in the attitude of a man much beset. Murder and I got to our feet. The chief asked Tim for the address of Nostra, got it, and we left the office. The old black ball we were behind looked bigger than ever.

Night was pitch black, not a star showing nor a breath of air stirring. As I walked down the grimy sidewalk in a seedy section of town beside the chief, I had the feeling the whole earth was gathered in a hush, watching us, waiting for the next impossible death to happen.

The unpainted cottage that was Nostra’s was directly ahead. We’d come down and scouted the place. Then we had dinner, Murder acting unhurriedly for a man slated to freeze to death sometime during this hot, hushed night. We’d waited for darkness, for the chief wanted to give that place a thorough going over.

We paused a hundred feet up the sidewalk. Except for the bar down on the corner with the lonely sounding, tinny jukebox, the street was deserted. We went on toward the cottage, clinging to shadows. We were at the edge of the yard, when Murder laid his hand on my arm. We dropped behind an unkempt shrub.

A moment later footsteps, quick, nervous, came across the sagging porch, down the walk. The shadowy figure reached the sidewalk, paused a moment. Yellow tongues from the street light touched a face, a neat figure. She was blonde and trim. Dim as it was, the street light told us she was young and lovely. She’d been inside Nostra’s shack, without any lights burning. Prowling, hunting maybe.

She turned left on the sidewalk. When she was fifty feet away, the chief touched my arm. We fell in behind her. She was hurrying along without a backward glance. It wouldn’t be too hard to keep her in sight.

The blonde got a cab at the first hackstand. She wasn’t half a block away when we’d grabbed a taxi and surged into traffic behind her. She went across town, to Cedarwood Forest, the swankiest development in town, a section of wide boulevards lined with stately cedars. We watched the tail light of her cab. It slowed, turned in the white driveway of a hedge-bordered estate.

Murder gave our driver orders to drive on past. Half a block away, the chief paid the cab, and we got out and walked back. As we cut into the edge of the wide, terraced lawn, Murder said:

“This, Luke, is one of the Wendel Hobbs’ houses. His summer place, I believe. Think it over.”

As we moved like deeper shadows against the night across the lawn, I thought it over. Before, this case had been impossible. Now it was also gigantic.

Wendel Hobbs was the controlling hand behind half a dozen huge companies, a chain of paper factories, a chemical works, a major stockholde in a steel mill. He was retired from active business, eighty years old, becoming a bit doddering in his senile years, according to a couple of newspaper columnists who’d spotted him at one or two racy night spots. He had so many millions that he and his heirs couldn’t count his money in their lifetimes.

The chief found a — French door at the side of the house that opened quite easily. He hissed to me, and I inched my way through the dense shrub_I moved up beside him. We were in the Hobbs mansion.

We stood a moment, getting our bearings. This was evidently the library. Faint light filtered in from the hallway. Books, hundreds of them bound in the finest morocco, lined the walk. Here and there was a rather silly bit of bric-a-brac Hobbs had probably paid a fortune for just for amusement in his waning years.

From somewhere we could hear the subdued murmur of voices. The lawnlike carpet deadened our footsteps. We heard a woman’s voice rise and say, “I tell you, Wendel, I did the best I could!”

I was willing to bet it was the blonde talking. It was her kind of voice. Velvet, even with the strained note in it.

Near the library door, Murder drew his flashlight, shaded it, played it over a scroll-legged desk. He whistled softly between his teeth. I looked over his shoulder. He had raised the blotter on the desk. Beneath it was a packet of carbon copies. He thumbed through them. There was a carbon copy of every warning Nostra had sent out. Frank Snow. Loren Cole. Gregory Sloan. Abner Murder.

Quietly, the chief let the blotter fall back on the desk. “Hobbs,” he said. “I suddenly want to talk to old Wendel Hobbs very much.”

The hall was lighted by a brilliant chandelier. Murder inched his head out the library door, scouted the hallway with his gaze. He tugged my sleeve, and we ventured out into the glaring light.

The sound of voices was coming from a room up the hall to our left. We started toward it. At that moment footsteps sounded in the back of the hall. It was probably a servant, but we didn’t want to find out at the expense of being caught in the middle of the hallway.

We lunged silently toward a door at our right, grabbed a knob, eased inside before we were spotted. Murder’s insatiable curiosity caused him to turn on his light to see the sort of room we had ducked into.

It was a den of sorts, a big lounge, some leather easy chairs. A rack on the wall held a few loving cups and guns. There was a huge fireplace. Before the fireplace lay two men clad in the garments of workers. It didn’t take a second stab of Murder’s wan, yellow light to show that both men were dead.

I stood back while Murder bent over the two dead men. I didn’t like their staring eyes or the neat bullet holes in their temples. The chief straightened, snapped his light off. I felt his presence move over near me.

I said, “Who are they?”

“How should I know?” he sounded irked. “Their pockets are as empty as the Jordan brain. However, one little slip was made.”

“Which is?”

“On the inside of the bib of their overalls. A little cloth label. No one would think of looking for it there, except a laundry. The overalls belong to the Apex Window Washing Service.”

“Does that make sense?” I asked, after thinking it over.

“Not yet,” he said. “But it will — if I freeze in the attempt.” I sensed the strain in his voice. I had a hunch he was thinking of his blonde wife, Jo-Ann, and the Murder children. His family was never far from his thoughts when he was working on a case, especially a case as coldly and deliberately executed as this one was. The chief could never quite forget that somebody, someday, might take a grudge out on his family.

We listened for long, thick minutes. The footsteps in the hallway had died. There was no movement, no sound, until we opened the door and again heard the murmur of voices up the hall.

This time we made it to the door which concealed the owners of the voices. Murder palmed the knob. A woman talking; the cracked tones of an old man. The chief opened the door.

There was an enormous fireplace in this room too. Before it, his hands clasped behind him, stood an aged, thin man, slightly stooped, his hair a white mane. I’d seen his picture in the papers, Wendel Hobbs.

A woman sat in a high-backed deep chair near him. At the sound of our entry she jumped to her feet. It was the blonde we’d seen coming from Nostra’s house, all right. Getting a good look at her, I saw that my first assumption had been right. She was a blood-pressure raiser, definitely. A Miami beauty contest would have been a snap for her blonde, green-eyed perfection. But now her face was like chalk.

Wendel Hobbs said, “What’s the meaning of this? I’ll have you—”

“We just want palaver,” the chief said. “Don’t get apoplexy.”

The blonde said, “Who are you?”

“A civil question,” the chief said laconically, “demands a civil answer. We are private detectives. I’m Abner Murder, this is Luke Jordan.”

Wendel Hobbs made a sound that sounded almost like a groan. He drooped loosely in a chair, his faded blue eyes seeming to sink in his head.

The chief said, “I gather from your reaction, Mr. Hobbs, that you don’t exactly welcome a detective on the premises.”

Hobbs gripped the arms of his chair to still the trembling of his hands. He forced harshness into his voice. “I don’t welcome you. Either leave, or I’ll call the police.” His eyes drank in the hard, knowing smile on the chief’s lips, the light in the chief’s eyes, which were still blue but no longer baby-looking.

“It depends entirely on you, Mr. Hobbs,” Murder said. “If you want to call the police, there’s a very expensive ivory telephone on that table.” Hobbs slumped in his chair.

The blonde was still standing. “Introductions haven’t been completed,” Murder said.

“I... I’m Linda.”

“Linda?”

“Yes... just... just Linda.”

“I see,” Murder mused. “Your last name is your own. Keep it quiet if you want to. But I’d like to ask you what you were doing in the house of a crystal-gazer named Nostra tonight.”

She tried to laugh. “I? In what house? I don’t believe—”

“We saw you come out of the place,” Murder said coldly. “We know you were there.”

She took a turn about the chair, her long, red-nailed fingers gripping the back of it. “It’s none of your business, Mr. Murder.”

The chief regarded her for a long moment The fire crackled; the only sound save the rising murmur of the wind outside. “All right,” Murder said, “we’ll play it that way.”

He turned to Hobbs. “Maybe you’ll be more communicative, Mr. Hobbs, and tell us who the two dead men are in the room across the hall.”

The blonde Linda almost fainted, reeled against the chair. Hobbs rose, doddering, slumped. He looked from Murder to me, back to the chief, a very old man. He shuffled to a high secretary beside a huge window, seemed to be gazing out at the night. Then he turned from the secretary, and there was a gun in his hand. He wasn’t trembling now, either. He was cool with a coolness born of desperation. He would use that gun, I knew.

“I don’t know anything about those men, Mr. Murder. I came home tonight and there they were. I was waiting for a chance to get them out of the house. I’m sorry you came along.”

“What do you intend doing now?” I asked.

“Whatever I can do,” he said huskily. “Whatever I have to do. The last few days have been extremely trying ones, gentlemen. May I plead with you not to push me further.” He motioned with the gun, took a step toward us. The chief and I moved under the gun’s bidding.

“Through that door,” Hobbs said. We backed out into the hall, down the hallway to another door, and Hobbs added, “In there.”

I fumbled the door open. It was a large linen closet. “Keep moving, please,” Hobbs requested. Murder and I backed into the closet. The old man slammed the door, shutting us in darkness. There was the faint sound of Hobbs’ footsteps retreating down the hall.

I lunged against the door. Murder caught my arm, pulled me back. “Just take it easy, Luke. Give the old boy a few minutes to get away. We won’t force him to start shooting at us, and get him in any more hot water than he is already.”

“So he’s innocent, huh?” I said sourly. “With two dead men in his den, he’s innocent?”

I felt the chief’s shrug. “He’s making too many mistakes to be guilty, Luke. He’s so scared he isn’t thinking straight, all in a muddle. He intends now to get rid of the pair of dead men, thinking vaguely he’ll tie the police up with the lack of a corpus delicti. But he didn’t take our guns, did he? He’s in such a dither he can’t see the loopholes, such as us getting out of here and going straight to the police.”

“So we wait, huh?”

“Might as well. Anyway, a frightened innocent man is a dangerous thing. You poke your head out of that door, you’ll get a noggin full of lead — which would at least put something in the empty apace.”

I was framing a retort to that one when the faint sound of a car motor, racing, somewhere outside drifted to us.

“Hobbs is on his way,” Murder said. “Let’s get a move on.”

We pounded on the door for perhaps thirty seconds; then a key grated, the door swung wide. A goggle-eyed servant took one look at us stranger: in his linen closet and let out a yell. Murder shoved him to one side and we got out of that hallway, slamming the massive front door behind us, like convicts with hungry bloodhounds on our heels.

Chapter III

The hospital corridor was white, bright with light, clean with the odor of anesthetic and germicides. The door to Gregory Sloan’s private room was just ahead of us, down the corridor. He was evidently much improved. His door was standing open.

As we neared, we heard his voice, “I appreciate your coming to visit me, Miss Smith. You are a good secretary, but when I tell you to come in my office at one thirty, you shouldn’t come at one thirty-five, just as you shouldn’t have brought the flowers tonight. They’re lovely, but my hay fever, you know.”

A girl stammered something. As We moved into the doorway she bade her boss, Gregory Sloan, good-by and speedy recovery, saying she would take care of the office while he was in the hospital. He assured her that he was going home in an hour or so, breaking off as he saw us.

His pale brows lifted. The chief said, “I’m Abner Murder, Mr. Sloan. This is Luke Jordan, my assistant. We’re—”

“I know. Detectives of the private variety. I’ve heard of you, Mr. Murder. Sit down.”

The chief took the chair at the side of the bed. I stood at the foot of the white iron bed.

Murder started to say something, but quick footsteps sounded in the corridor, turned in the room. She saw the chief and me too late to turn back. It was a blonde goddess named Lind... Her face became as lifeless as the color of cotton batting when she saw Murder and me. She stood just inside the doorway, frozen.

Gregory Sloan missed her reaction. “Gentlemen,” he said, “my wife.”

Murder had risen. He made a mocking, faint bow to the girl. “We’re happy to know you, Mrs. Sloan. I would almost swear that I’ve met yon some place before.”

I watched the pulse pound is her throat. Gregory Sloan laughed. “I doubt that you’ve met Linda, Mr. Murder. She’s a very quiet, homey little woman.”

“Oh, I’m sure of it,” the chief said. “Very quiet, homey.” His eyes were drilling into her. Her own lovely green orbs were stricken, begging him to keep silent about trailing her from Nostra’s shack and finding her in the house of a rich man who had two very real corpses in his den.

“I... I really don’t get around much, Mr. Murder,” she stammered. “Another girl, perhaps? Someone who looked like me?”

Murder let her hang for an agonizing moment. Then he said, “Naturally. Another girl.”

She almost slumped with relief. She fumbled in her bag, found a cigarette and lighted it. She stood over by the window as Murder took the chair by the bed again, and explained to Gregory Sloan that we were interested in the deaths foretold by Nostra and would appreciate a few answers. Sloan told him to fire away. He and the chief talked.

As far as I could see, Murder got exactly nowhere. We learned nothing we hadn’t known before. Gregory Sloan had received the note from Nostra, had been alone, had touched nothing that might poison him. He was unable to explain the impossible, he said. Neither could he advance a theory as to how Frank Snow had drowned with no water present, or how a man might be killed in an accident with a toy plastic automobile.

So for my money the visit was a flat pan, but when we left the hospital, there was a smile on Murder’s chubby face. “I know how the whole thing was done, Luke,” he said in the darkness outside. “I can explain the things that happened ho Frank Snow, Loren Cole and Gregory SIoan. I can also explain the two dead men in Wendel Hobbs’ den. I think I can even lay my finger on the killer!”

“But how—”

“You can’t see It?” he said in mock surprise. “Gracious, Luke, you’ve seen every angle of the case that I’ve seen. Every fact known to me is Tight under your nose.”

“Okay, crow awhile,” I said sarcastically. “But in the meantime, why don’t we nab this killer?”

“Because,” he said slowly, “the most important element is still missing. We’ve got to find a motive.”

“So what do we do?”

“We go to the key to the puzzle — Wendel Hobbs. We wait. We hope that we don’t have to wait too long. That we don’t have to wait until I freeze to death here in the middle of August!”

Night had deepened. Despite the sweat gathered in the small of my back, the ground was cold, especially if you were lying full length on it. Dew had risen, seeping into my coat, and the night wind had grown.

I was hunkered behind one of the shrubs dotting Wendel Hobbs’ spacious, terraced lawn. Murder was on the other side of tho flagstone walk, hunkered behind a shrub that was a twin to this one. We had a full view of the front and either side of the house.

I kept watching the light burning in the corner of the house, the shadow pacing back and forth across the face of the light, a silhouette against the window. Murder had assured me that the pacing shadow was old Wendel Hobbs, that eventually he would stop his pacing, turn out the light and go somewhere. Personally, I guessed the old geezer would go to bed. That’s where I wanted to be.

I knew the chief would bawl me out if I dared strike a light to smoke. So I crouched there in misery, cursing the day I’d hired myself out to the dumpy little man with the dimples and baby-blue eyes.

Then my thoughts broke off. The light had gone out, just as Murder had said it would. A door slammed. A long minute of silence, during which even the wind paused. Then the sound of footsteps coming down the path, the steps of an old man made sprightly by nervous reserve energy.

The shadow passed down the walk. As the chief had assured, it was Hobbs and he was going somewhere. A light topcoat with the collar turned up and a hat brim pulled low almost obscured his face. He didn’t want anyone to know where he was going, not even his chauffeur.

He turned right at the sidewalk. Murder and I gave him a moment, then cut across the lawn and fell in behind him.

It wasn’t an easy job, this task of shadowing. Hobbs was leery, cautious. His head kept jerking around, the movement freezing Murder end me in shadows.

Hobbs walked a block, turned. He approached a small park, stopped, looked around. He stood at the edge of the sidewalk for what seemed to be five dragging minutes. The chief and I inched closer to him until we could have whispered to him from the shelter of twin willow trees just off the sidewalk behind him.

Then up the street twin lights flashed. Automobile headlights. The ear was parked a block away at an intersection. Even I didn’t miss that carefully planned detail. The car could have gone in any of four directions should anything go wrong.

Those headlights snapped on and off again, then on once more and stayed lighted. Old Wendel Hobbs reached beneath his coat, pulled out a long, flat package and tossed it on the edge of the street. The car’s motor was roaring and the headlights raced closer. Hobbs turned quickly and started walking back in the direction he had come.

Murder bawled some kind of order to me. Things happened so fast that, even though I didn’t catch his command, I fell in step behind him as he came hurtling from the shelter of the willow tree. His body was bent, his feet pounding. He was headed directly toward the street.

It was a hop and jump; it was nip and tuck. Murder reached it without breaking stride and scooped up the package Wendel Hobbs had tossed in the street. Those headlights were glaring, right on top of us it seemed. My heart was trying to tear its way out of my throat

I heard Hobbs yell. The roar of the car’s motor as the quick-thinking driver gave it the gun.

He twisted the wheel, slashed across the street toward us. If we had paused to turn and take the short way out of the street, he would have got us. Instead, we just kept right on going like the devil was lashing our heels, into the broad, vacant lot directly across the street.

The looming headlights missed us by inches. I heard Hobbs yell again as the chief and I plunged into undergrowth. Murder clutched that long, flat package in his hand. I hoped it was worth all this.

Tires shrilled behind us as brakes were slammed. Car doors opened and shut. The quiet, widely separates estates of elegant Cedarwood Forest had never seen tire like of this.

Half a dozen rough voices rose in the night. Footsteps charged into the undergrowth behind us. Somebody back there ran into a tangle of brambles and cursed.

Somebody else was too much on edge. He fired three quick shots. The man is the brambles cursed some more. “Cut it you fool! Wait’ll we get our hands on them, then we’ll slit their eyes out!”

The chief and I reached a clearing. He drew up short. We’d be spotted in the dim moonlight in the cleared space. And we couldn’t turn back. Personally I valued my eyes too much.

I stood panting during a second that seemed like an eternity. Then Murder shoved me, grabbed a low branch on a tree, swung himself up. I followed suit, easting up on the limb beside him. We pressed against the trunk of the tree, trying to make ourselves a part of it, and waited.

The half dozen men back there would have been tops in their trade in a dark alley with knives in their hands, but they weren’t woodsmen. They made too much noise as they beat the underbrush, coming steadily toward tho clearing. Then they were silent. I knew they had drawn up, ringing that side of the clearing not a dozen feet from our tree.

They were more cautious now. Seconds ticked away and the chief and I saw dim blobs moving out into the clearing. One shadow passed beneath our tree. I could have spit in his eye if he had looked up.

But he didn’t. They worked their way to the other side of the clearing. Somebody said, “There’s another street over here. They musta got away that way.”

“Nice going, nice going, ain’t the boss gonna like this?” somebody else said bitterly.

A third voice added, “We better scram outta here. They got away. Some of the dudes living around here might have heard Duvarti shooting and called the bulls.”

So Duvarti was in that group of men. That meant Krile probably would be, too.

The dim shadows below turned and came back across the clearing. Moments later the motor of the car started. We listened to the sound die away. Our playmates were gone.

Murder and I dropped out of the trees. “Scooped their prize right from under their noses, eh, Luke? I guess old man Hobbs is back home by this time, quivering in his slippers.”

“And what did we scoop?” I asked.

In answer, Murder shielded his light, flicked it on. He handed me the package. I ripped open the end. It was more money than I’d ever dreamed I would see in one time in my whole life. It was a package of thousand dollar bills. There must have been at least a hundred of them.

We didn’t get to enjoy it. A voice in the darkness behind us said, “One move, gentlemen, and I can promise you that you’ll never move again!”

The light of a flashlight spread over us. We turned slowly. “Drop the package.” Murder dropped it.

I’d heard the voice before. It was the voice of Nostra, the guy who owned the crystal.

He chuckled over the gun in his hand. “Did you really think we would give up so easily, Mr. Murder? I guessed you would be hiding somewhere close around. You really didn’t have time to make a getaway. So I stayed behind with a couple of the boys. Two friends of yours. Rick Duvarti and Burt Krile.”

Duvarti and Krile moved up out of the darkness to stand beside Nostra.

“I thought you were in jail,” the chief said.

“It was easy enough to get out,” Nostra said. “I’d committed no real crime. I paid my bond and will have to appear in police court next Tuesday because I slapped the cop. You know as well as I that they had nothing to hold me on.”

Duvarti gave his short, nasty chuckle, came forward and warily picked up the package of money at Murder’s feet.

“You have some admirable traits, Mr. Murder,” Nostra said. “Few men would have thought of trailing Wendel Hobbs and snatching the package from under oar noses. Few men will be so honored in their manner of dying. We will retire to the street. I’ll signal with my light. The car, which is now parked down the street, will turn, come back, and pick us up. If you want to die suddenly, make a break. If you want a few hours more of life, remember that the crystal never lies.”

“You mean—” I gulped.

“I mean,” Nostra explained coldly, “that I have a friend who owns a slaughter House. You ape aware of the refrigerating systems in slaughter houses, of course? Refrigerators that can hold a ton of pork or beef and freeze it solid. We will strip you, gentlemen, and do our best to keep you from being cozy inside the refrigerator. When you have finally expired, about dawn, we’ll smuggle you to a hotel room. A post mortem will prove definitely that you froze to death in August in a hotel room you apparently spent the night in. Quite cunning, don’t you think?”

He laughed, and I was feeling that refrigerator already.

Chapter IV

It was crowded in that heavy seven-passenger sedan. But there was no chance to make a break. These lads had been recruited, because they were fast on the trigger, knew their business, and would shoot their own brothers for a grand note.

I sat beside Murder, listening to his jerky breathing. The sedan wound its way through back streets, where the one short yell we might be able to give would do no good. Streamers of fog began to slither across the headlight beams. The particular smell of grimy water lapping piers bit my nostrils. We were down in the waterfront section of warehouses, docks, slums — and slaughter houses.

The sedan drew to a stop before a huge, weather-browned building. One of the men got out of the car, opened a broad, creaking door. The sedan moved forward, tipped down, went down a wooden incline.

Nostra said, “Last stop. You will keep your hands over your heads, gentlemen.”

The chief and I got out. In the beams of the headlights we saw that we were in a huge, boxlike room. A row of hand trucks stood to one side. Empty boxes were stacked along one wall. Overhead tan a series of steel rails, huge, gleaming meat hooks hanging from pulleys here and there, on which huge slabs of meat were shunted toward the refrigerators at the far end. The slaughtering pens were not here, but were in the rear section of the building; yet the odor of the pens hung over everything.

Krile carried a flashlight, walking directly behind us as the chief and I moved forward with our hands above our heads. I knew Nostra had been lying about one thing. Whoever owned this packing house was not a friend of his. It was a legitimate place. The owner would never suspect it had been broken into and two men cooled in its refrigerators.

The lights of the car snapped off. We moved forward in single file, footsteps echoing, Krile’s light a dim, lost finger in the vastness of the place.

It was a mistake all the way through on the part of Nostra. He shouldn’t have told us to keep our hands up. We shouldn’t have been walking single file with only one flashlight behind us. Nostra shouldn’t have been leading the procession with Murder directly behind him.

If Nostra had done none of those things, Abner Murder never would have grabbed the next meat hook we passed.

Murder’s arm snapped like a small load of dynamite behind the hook. The pulley wheels supporting the heavy, three-pronged hook on the gleaming rail zinged an angry cry as the hook left Murder’s hand.

Krile yelled and Nostra turned. The crystal-gazer jerked up his arm, his face contorted. He was only five feet away. He never had a chance. The sharp tip of the hook was on a neat level with his chin...

Then I was piling into Krile. I couldn’t wring the light from his hand, but I smashed it to the floor by throwing him. The light winked out. Krile thrashed, yelled. Everything was happening between heartbeats. Men were cursing and milling about in the Stygian darkness.

Murder’s hands found Krile’s face. Still Krile hung on to me. So the chief draw back bit toe and kicked. Hit aim was good. I beard Krile lose teeth, and he relaxed in unconsciousness.

Somebody tripped over me. I cursed in a reasonable facsimile of Krile’s voice. I got his gun, located the chief by feeling around for him. I fired the gun three times. I wasn’t aiming at anything, simply away from Murder and myself.

We dropped fiat on our faces before the last shot had died. Everybody started shooting, which is the spark I’d wanted to set off. They were still banging away in the dark, insane with panic, when the chief and I inched out of one of the packing house windows.

Four blocks away we found a drug store. Murder dropped a nickel in the phone and dialed headquarters. He got Tim Brogardus on the wire and told Tim about the little party in the packing house. “But never mind that, Tim,” he said, “send some of your minions to pick up the pieces. If any of them are still alive, we’ll want them for questioning. We especially want Duvarti and Krile to spill their brains. Krile at least will be alive, I think. You’ll find him on the floor unconscious.”

Murder paused. At the other end, Brogardus evidently had picked up another phone and was yelling orders to be dispatched to squad cars.

Then Murder said, “Here’s what I want you to do, Tim. Pick up Wendel Hobbs, Linda Sloan, and her piggish husband. Take them to my office. If you get there before we do, use one of your passkeys and wait. By the way, Tim,” he added, “you might have told your squad car lads that Nostra will be hanging around when they get to the packing house.”

Tim worked fast. The chief and I had to hoof several blocks to find a cab. We trudged up to the office and saw that the light was on. We opened the door, and they were there. Tim. Gregory Sloan. Linda Sloan. Wendel Hobbs.

Murder surveyed them, closed the door, took a turn around the room like a lecturer preparing to start his talk. The chief really lived at moments like these.

He addressed Wendel Hobbs, “I asked you here, Mr. Hobbs, in order that you might enjoy knowing the identity of the person who was wringing money from you.” Murder fastened his gaze on the lovely Linda Sloan.

She half rose from her chair. “No!”

“Yes!” the chief mimicked sardonically. “You want details? Here they are. The whole business was a combine to extort money from wealthy men. Scare them half to death, stage a lot of spectacular stuff, and demand money as the price of their staying alive. That’s the motive. Simple enough?

“Except for Frank Snow. He was killed because he was getting wise to the setup and trying to muscle in. Just as Luke and I were slated to be killed because you weren’t sure Snow hadn’t talked to us. You knew he’d sent us a packet containing evidence with an envelope inside the manila envelope sealed and inscribed with something like ‘Not to be opened except in case of my death.’ He was doing that to hold you in line.

“But you found out he’d sent the packet to me. You had Krile and Duvarti ready to lift it, but you didn’t know whether or not I was wised up to a certain extent already. So I was supposed to be removed in the usual spectacular way. For every one of the deaths served two purposes — they created confusion, thereby covering the identity of the murderer; and they created fear in men like Wendel Hobbs who were going to pay off in millions.

“Loren Cole was one such man. But he didn’t pay, so he was made an example to others who might get ideas of balking.”

“But how, Ab?” Tim Brogardus demanded.

“Frank Snow and Loren Cole were murdered by window washers,” the chief said. “Nostra was just a puppet in the game, contacted and hired to write these notes, all of which built the bizarre in the minds of future extortion victims.

“It was a simple matter to remove two workers from the Apex Window Washing Service this morning with bullets in their temples. Then a couple of huskies don the uniforms, drop the lines and platforms and start washing windows — until they get to the office of Loren Cole and Frank Snow. They take those offices one at a time, working as a pair. They open the window — or if it’s locked they tap on it — and tell Cole and Snow to please excuse them, that they want to wash the inside of the windows.

“So Cole and Snow, possibly even experiencing a momentary first instant of fright, think nothing more of it. Cole turns his back and they break his neck, place his body on the floor along with a toy automobile they’ve stolen from his home or bought in a dime-store toy department.

“Snow turns his back, and the two of them cram his head in a pail of their water. They dry his head and face, and he’s apparently drowned with no water near. Just who the two ‘window washers’ were is a minor detail that we’ll And out when your boys really get rolling to tie up the loose ends, Tim.”

“No!” Linda Sloan sobbed. “I wasn’t behind it! I didn’t do it!”

“But you will talk!” Murder said. “Not on the stand of course, for a woman can’t testify against her husband. But you’ll tell us enough off the record to make a confession come easy and lighten the grief you’re going to carry. You were an accomplice, working from inside, putting pressure on the rich guys and building the idea of Nostra and death! Not to mention the way you worked on Hobbs with the bodies planted in his den!”

Gregory Sloan bounded to his feet. “I won’t take your insinuations, Murder! I’m a sick man. I’ve just been out of the hospital a few hours. I was in bed when I graciously consented to come here when Brogardus phoned me.”

“Sit down,” Murder said coldly. “You’re a killer and you’re going to take all the insinuations I can hand out. You were the man behind it all. It’s no secret around town that the last election upset your apple cart. So you picked this way of getting rich quick.

“Sure, you were poisoned. You included yourself right in your list of victims. You even sent the carbon of the note you’d supposedly received from Nostra along with the other carbons that went to Wendel Hobbs. Carbons that were one more tiny example of the dozens of ways your pressure mounted on your victims. You knew that if you were among the victims, there was a good chance you might get caught. One of your hoods might have talked a little too much. There might have been a slip somewhere.

“I suspected you of giving yourself a slight dose of poison — not too much of course — this morning when Tim told me your secretary had rushed in your office and given you luke warm water and baking soda, a good emetic. The water and soda were both on your desk where you’d put them in advance!

“I was positive it was you, Sloan, when I came up to your hospital room and heard you blessing out your secretary for coming into your office at one thirty-five when you had told her in advance to come in at one thirty sharp. That five minutes could have been fatal had the poison been stronger.

“We’ve got Krile. He’ll talk. Linda here is in a jam. She’ll talk. How long do you think you’ll last, Sloan?”

Gregory Sloan whimpered, bolted for the door. I hit him, and he staggered back across my desk, his hand to his cut lips. He slouched there and held out his other hand to Wendel Hobbs.

“Help me! You’ve got money. You can hire lawyers! I’m sorry I did what I did to you. Your money is in my safe at home. Help me.”

Wendel Hobbs looked at Sloan, and Sloan’s words died. His piggish gaze dropped before that of the old man. I looked at Sloan, his pleading words to the man he had victimized echoing in my ears. I knew that not even Abner Murder would ever fully understand the criminal mind. Tim mumbled a thanks, pulled his gun, and herded Linda and her broken, sobbing husband out. The door closed behind them. The chief turned to Hobbs and cleared his throat.

“Mr. Hobbs, I feel I should tell you that my price for recovering lost or stolen property is a mere ten per cent. Now since your money is now known to be neatly tucked away in Gregory Sloan’s safe.”

Old man Hobbs laughed, pulled a checkbook from his pocket. Without hesitation he wrote a nifty. Ten grand, with the notation in the corner of the check, For services rendered — in more ways than one.

“I’ll watch the company I keep, Mr. Murder. I met Linda Sloan at a rather wild party one night. She was the first contact.”

He shook the chief’s hand and walked out. Murder sat down, blowing tenderly on the check. “Luke, call my wife and tell her to put on the coffee and break out the cream puffs. We’re doing to have a celebration!”

Celebration? With ten grand who — besides Abner Murder — would care anything about cream puffs!