Television, the movies, and computer games fill the minds of their viewers with a daily staple of fantasy, from tales of UFO landings, haunted houses, and communication with the dead to claims of miraculous cures by gifted healers or breakthrough treatments by means of fringe medicine. The paranormal is so ubiquitous in one form of entertainment or another that many people easily lose sight of the distinction between the real and the imaginary, or they never learn to make the distinction in the first place. In this thorough review of pseudoscience and the paranormal in contemporary life, psychologist Terence Hines shows readers how to carefully evaluate all such claims in terms of scientific evidence.

Hines devotes separate chapters to psychics; life after death; parapsychology; astrology; UFOs; ancient astronauts, cosmic collisions, and the Bermuda Triangle; faith healing; and more. New to this second edition are extended sections on psychoanalysis and pseudopsychologies, especially recovered memory therapy, satanic ritual abuse, facilitated communication, and other questionable psychotherapies. There are also new chapters on alternative medicine and on environmental pseudoscience, such as the connection between cancer and certain technologies like cell phones and power lines.

Finally, Hines discusses the psychological causes for belief in the paranormal despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. This valuable, highly interesting, and completely accessible analysis critiques the whole range of current paranormal claims.

Terence Hines

PSEUDOSCIENCE AND THE PARANORMAL

Second Edition

This book is dedicated with love to

my daughter

Clare Rose Hines,

who brings me more joy than I could ever have imagined;

her mother,

Mary Ruth Dolson;

and her grandparents,

Jessie Rose Stevens Dolson (1935-1997)

and

Roger J. Dolson Sr. (1932-2003)

PREFACE

The first edition of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal appeared in 1988. Much has changed in the area of paranormal claims and beliefs since then, but much has also remained the same. To reflect this, two new chapters have been added to the present book. One chapter covers “alternative” medicine and replaces that on health and nutrition quackery from the 1988 book. Chapter 12 covers the actual science of several of the various hysterical responses that have broken out over alleged environmental health hazards such as power lines, PCBs and cell phone radiation. The chapter previously titled “Psychoanalysis” has been renamed “Pseudopsychology” to reflect the fact that psychoanalysis is far from the only quack psychotherapy out there. The other chapters have been updated and expanded as needed. As in the 1988 book, I have heavily referenced the text so that readers who would like to read more on a particular topic will be able to find the relevant primary sources with ease.

As with any book, this was not a project I completed alone. I would like to thank numerous friends and colleagues who helped in many ways, among them by answering questions and tracking down obscure publications. The Interlibrary Loan staff at the Mortola Library on Pace University’s Pleasantville, New York, campus was especially helpful in tracking down often obscure articles. Of course, any errors are mine alone.

Chapter 1

THE NATURE OF PSEUDOSCIENCE

What is pseudoscience? It’s difficult to come up with a strict definition. In the real world things are not clearly delineated but surrounded by gray areas that doom any hard definition. As the term implies, a pseudoscience is a doctrine or belief system that pretends to be a science. What distinguishes pseudoscience from real science? Radner and Radner (1982) and MacRobert (1986) have discussed criteria for separating real science from pseudoscience and for helping to decide whether a new claim is pseudoscientific.

The most common characteristic of a pseudoscience is the nonfalsifiable or irrefutable hypothesis. This is a hypothesis against which there can be no evidence—that is, no evidence can show the hypothesis to be wrong. It might at first seem that such a hypothesis must be true, but a bit of reflection and several examples will demonstrate just the opposite. Consider the following hypothesis: “I, Terence Michael Hines, am God incarnate, and I created the universe thirty seconds ago.” Now, you probably don’t believe this hypothesis, but how would you go about disproving it? You could argue, “You say you created the universe thirty seconds ago, but I have memories from years ago. So, you’re not God.” But I reply, “When I created the universe, I created everyone complete with memories.” We could go on like this for some time and you would never be able to prove that I’m not God. Nonetheless, this hypothesis is clearly absurd!

Creationists, who believe that the biblical story of creation is literal truth, often adopt a similar irrefutable hypothesis. They claim that the world was created less than ten thousand years ago. As will be seen in chapter 13, vast amounts of physical evidence clearly refute this claim. All one has to do is point to something older than ten thousand years. Backed into a corner by such evidence, creationists often rephrase the creationist hypothesis in an irrefutable form. They explain the clear geological and fossil evidence that dates back millions of years by claiming that God put that evidence there to test our faith. An alternative version is that the evidence was manufactured by Satan to tempt us from the true path of redemption. No evidence can refute either of these versions of the hypothesis, since any new piece of geological or fossil evidence can be dismissed as having been placed there by God or Satan. This does not make the hypothesis true—it just makes it nonfalsifiable. Such a hypothesis contributes nothing to our understanding of the physical world.

Another example of an irrefutable hypothesis comes from a doctrine not usually considered a pseudoscience (but which meets the criteria, as will be seen in chapter 5)—psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud believed that all males had latent homosexual tendencies, but that in most males these tendencies were repressed. Clearly, homosexual males have homosexual tendencies. But what about heterosexual males? To determine whether the hypothesis that all males have repressed homosexual tendencies is false, you could give some sort of test for homosexual tendencies. What if you failed to find such tendencies? The standard Freudian reply is that the tendencies have been so completely repressed that they don’t show up on the test. Given this irrefutable hypothesis, no test could show that heterosexual males don’t have latent homosexual urges. No matter how sensitive the test, the reply can always be made that the urges are so deeply repressed that they don’t show up on the test.

Those who are skeptical about pseudoscientific and paranormal claims are frequently accused of being closed-minded in demanding adequate evidence and proof before accepting such a claim. But who is really being closed-minded? As a scientist, I can specify exactly the type of evidence that would be required to make me change my mind and accept the reality of astrology, UFOs as extraterrestrial spacecraft, or any other topic considered in this book. But the believer, who likes to paint him or herself as open-minded and accepting of new possibilities, is actually extremely closed-minded. After all, the irrefutable hypothesis is really saying “There is no conceivable piece of evidence that will cause me to change my mind!” This is true closed-mindedness.

One more point should be made about irrefutable hypotheses: Although they are nonfalsifiable, they are not nonverifiable. That is, they could be shown to be true. The Freudian hypothesis about males’ latent homosexual urges could be verified if all males did show such urges on some sensitive test of sexual preferences. So, irrefutable hypotheses are only that—irrefutable. They could be verified, if the evidence to support the hypothesis existed. Of course, the promoters of irrefutable hypotheses have been forced to fall back on them precisely because no evidence exists to support them. Thus, an irrefutable hypothesis is a surefire sign of a pseudoscience.

A second characteristic of pseudoscience is the proponents’ unwillingness to look closely at the phenomenon they claim exists. In other words, careful, controlled experiments that would demonstrate the existence of the phenomenon—if it were real—are not conducted. The reality of the phenomenon is uncritically accepted, and the need for hard data and facts is belittled. MacRobert (1982) gives an excellent example in the work of George Leonard (1976), who believes that official photographs from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) show that “somebody else is on the moon.” Leonard contends that he has discovered this secret and is trying to inform the public about it in spite of a massive conspiracy of silence. Leonard’s evidence consists of low-resolution NASA photographs, many of them poor reproductions rather than crisp originals. The objects Leonard sees, such as huge bridges and construction equipment of various types, are all just at the limit of resolution of the photos he uses. MacRobert points out that “when he had a chance to get better photos and see the terrain more clearly, he didn’t. One of his pictures is supposed to show miles-long bridges. The photo is a very distant shot, and the bridges are the vaguest smudges. Equally good close-ups have been taken of the bridge areas, and if the bridges were there, they would reach from one side of the photos to the other like a wall poster of the Golden Gate. For some reason Leonard did not get those particular close-ups, readily available from NASA. He was unwilling to look carefully” (p. 47) Oberg (1982) has discussed Leonard’s errors in detail.

It will be seen throughout this book that there is a general unwillingness on the part of promoters of pseudoscientific claims to look carefully at the evidence they put forth to support their claims. This contrasts, of course, with the behavior of scientists, who try to be extremely careful in examining evidence.

What Radner and Radner (1982) term “looking for mysteries” is another common feature of pseudoscientific claims. Here the proponent searches for allegedly unexplained phenomena and says, in effect, “There, Science, explain that.” If science can’t fully explain the phenomena, reasonable explanations are ignored or dismissed and the proponent concludes that his pseudoscientific theory is supported. This type of accumulation of stray events is best illustrated by UFOlogists, who claim that unidentified flying objects (UFOs) are extraterrestrial spacecraft. Proponents of such claims compile long files of UFO sightings and other UFO-related phenomena. The skeptic is then told that unless he can explain away every single report, the theory that UFOs are extraterrestrial craft must be true. In other words, the burden of proof is placed on the skeptic to disprove the claim.

In reality, the burden of proof should rest squarely on the one who is making the extraordinary claim. This is because, as we have seen, it is often impossible to disprove even a clearly ridiculous claim. Consider the claim that Santa Claus is a real, living person: What evidence might one offer for such a claim? The proponent might point to the hundreds of children who say every year that they have seen Santa Claus. They can’t all be lying, can they? Surely there is some grain of truth in all these reports. And didn’t the astronauts on Apollo 8 report sighting Santa Claus from space when they were between the earth and the moon? Skeptics will say that was just a Christmas joke, but NASA could be hiding evidence from the public. And how about packages that appear under the Christmas tree on Christmas morning inscribed something like “To Susan from Santa”? Where did they come from? The skeptic will point out that the vast majority of such inscriptions are written by parents to maintain their children’s belief in Santa, but what about the small number of cases that cannot be explained away so simply? They really do exist, of course, and are due mainly to packages getting mixed up in the mail. But the skeptic will never be able to explain away every single piece of evidence that the proponent puts forth as evidence of the physical existence of Santa Claus. This inability to explain away every bit of evidence should not, of course, convince one of the truth of the “Santa Claus is real” hypothesis. The burden of proof must rest on the proponent. He or she must bring forth clear, acceptable evidence that Santa Claus is real and not simply demand that skeptics explain away miscellaneous reports to prove that Santa doesn’t exist.

This may seem like a silly example, but the type of “evidence” listed above for the existence of Santa Claus would be more than sufficient to convince many proponents of pseudoscience that a real phenomenon exists. In fact, it was just such evidence—the testimony of two little girls and some photographs that they faked—that convinced none other than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes, that fairies really existed in the English countryside. The story is important because it illustrates how reversal of the burden of proof can lead to the uncritical acceptance of the most absurd claims.

The story starts in Cottingley, England, in 1917. Two girls—Elsie Wright, thirteen, and a cousin, Frances Griffiths, ten—claimed to have taken two photographs of fairies who played with them. Three more photos were apparently taken in the summer of 1920 (Sheaffer 1977–78). It was Doyle who brought the photos to the public’s awareness, and he later wrote a book arguing for the real existence of fairies, based largely on these photos (Doyle 1921). The photographs, one of which is shown in figure 1, have always looked fake. But neither this nor the inherent absurdity of the claim has stopped many people, including Doyle, from taking the existence of fairies seriously. As Sheaffer (1978) points out, UFOlogists have been interested in fairy sightings, believing they may be related to the UFO phenomenon and extraterrestrials. Various reports of fairies, leprechauns, and the like are all brought together to argue that maybe there really is some substance to the reports. And, again, the skeptic is challenged to explain away each and every report. Just as in the case of the Santa reports, however, it’s impossible to explain every case. For example, we can never expect each child who has reported seeing fairies to admit lying. But the Cottingley photos can be explained. They were—and this should come as no great surprise to the reader—a hoax. The “fairies” were cutouts from a children’s book, and many years later Frances and Elsie admitted the hoax (Cooper 1982). Crawley (2000) has described the creation of the photos and the hoax in detail. Finally, Sheaffer (1978) has subjected the photographs to computer enhancement and found evidence of a string that was used to hang the cutouts from shrubs while the photos were taken. So what began as a hoax and concerned a clearly absurd hypothesis—that fairies really exist—turned into pseudoscientific belief that required sixty years and much effort to put to rest. And none of this would have happened if the burden of proof had been on the proponents in the first place to provide adequate evidence of their claim—such as a fairy or a leprechaun in a cage. Instead, the burden was shifted to the skeptics who were told, “If you can’t explain away every photo and every report, then fairies must exist.”

Proponents of pseudoscience often complain that skeptics are unfair in demanding more proof for pseudoscientific claims than for the claims of “establishment” sciences. This is both true and reasonable, under the circumstances: Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary proof. For example, consider the following two claims about transcendental meditation (TM): (1) TM can make you feel better; (2) TM can teach you how to defy the law of gravity and float in the air at will. Most people would accept the validity of the first claim based simply on the testimony of several people who say that they felt better after they learned how to meditate. Clearly, one would demand more proof for the second claim. Most people wouldn’t accept statements from several people that they knew how to levitate at will. Additional evidence would be needed. Pictures wouldn’t do, because the TM movement has been known to fake photos of people levitating (Randi 1980). You’d probably demand that someone actually levitate right in front of you. And you’d want a professional magician present as an observer to ensure that no trickery was involved.

In short, you would demand more rigorous confirmation of the second claim than of the first. So not only is the burden of proof on the proponents of pseudoscience to prove their claims, but the burden on them is greater than on someone making a claim that does not challenge the bulk of known facts.

Proponents of pseudoscience often use myth and legend as support for their claims. After all, they reason, myths and legends have been around for a long time, so they must contain a kernel of hard truth. In fact, myths are primitive attempts to explain natural phenomena in a way that the culture using the myth could understand (Barnard 1966; Vitaliano 1973). Myths should never be taken literally. Thus, one can trace the modem Santa Claus myths back through Christian thought to Saint Nicholas, and the customs surrounding the giving of gifts at Christmastime (Revzin 1986). Nowhere, of course, is it ever suggested that the current image of Santa Claus, complete with sleigh and reindeer, is or ever was a real being. But anyone who took the modern myth literally would be fooled into believing that such was the case. Many proponents of pseudoscience have been similarly fooled.

Another characteristic of many pseudosciences is the failure of the proponents to change or update their theories in the light of new evidence. For example, in 1950 Immanuel Velikovsky put forward his theory of “worlds in collision” (see chapter 9). Knowledge of the solar system in particular and astronomy in general changed vastly in the thirty-two years between 1950 and Velikovsky’s death in 1982. Yet not once during that period did Velikovsky change his theories to reflect this new knowledge. Like many proponents of pseudoscience, he felt the theory was written in stone. It was, so to speak, revealed truth not to be changed by mere facts. If the facts don’t fit, the proponents of pseudoscience prefer to ignore the facts. The theory must be preserved at all costs.

This is rather ironic, as I suspect the general public’s impression is that scientists are conservative, closed-minded, stodgy folk who rarely change their minds. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. In the last thirty years all areas of scientific investigation have undergone radical changes. New theories have appeared, been useful for a time, then given way to even newer theories as new data and facts have demonstrated that the old theories were inadequate. Science changes so rapidly, it is frequently difficult to keep up with the changes even in one’s own field. This is in contrast, of course, to the pseudoscientists, whose theories almost never change. Again, if one looks at the actual behavior of scientists and pseudoscientists, it is clear which is really the more open-minded of the two groups.

The characteristics of pseudoscience discussed in this chapter may not permit one to determine with precision whether a specific claim or belief system is a pseudoscience. But they do offer some useful guidelines. As applied in the following chapters, which examine various areas of pseudoscience, these criteria should help readers determine whether specific claims and arguments are pseudoscientific or not.

THE PARANORMAL

The paranormal can best be thought of as a subset of pseudoscience. What sets the paranormal apart from other pseudosciences is a reliance on explanations for alleged phenomena that are well outside the bounds of established science. Thus, paranormal phenomena include extrasensory perception (ESP), telekinesis, ghosts, poltergeists, life after death, reincarnation, faith healing, human auras, and so forth. The explanations for these allied phenomena are phrased in vague terms of “psychic forces,” “human energy fields,” and so on. This is in contrast to many pseudoscientific explanations for other nonparanormal phenomena, which, although very bad science, are still couched in acceptable scientific terms. Thus chelation therapy, a popular bit of medical quackery, is said to remove calcium from clogged arteries when the chemical ethylenediamine tetraacetate (EDTA) is given. The specific claim is that EDTA binds to calcium, thus destroying material blocking arteries. Binding of one substance to another is a real and very important biochemical process. However, the claims of the chelation therapists are simply wrong (Bennett 1985; Richmond 1985–86; Yetiv 1986; Green and Sampson 2002), and the therapy is not effective. So the claims for chelation therapy are pseudoscientific, but not paranormal.

However, the boundary between paranormal and nonparanormal pseudosciences is often fuzzy. Different individuals may give different types of explanations for the same alleged phenomena. Thus, the claims that UFOs are extraterrestrial spacecraft is generally a pseudoscientific one (see chapters 7 and 8). But some UFOlogists, such as Vallee (1975), now argue that UFOs are really some sort of psychic projection. This transforms the phenomenon into a paranormal one. Similarly, Mack (1999) argues that we live in a universe of many dimensions and that UFO aliens are spirits (or some such) from these other dimensions

Another example concerns biorhythms (discussed in chapter 6). The pseudoscientific explanation of these alleged effects is that the rhythms are set at the moment of birth in the individual’s brain (Mallardi 1978). Attempts are then made to tie the claims for biorhythms in with what is now known about biological rhythms in humans and animals (Gittleson 1982). On the other hand, a “biorhythmist” in Oregon explained that the concept of biorhythms works because “it concerns itself with rhythmic flows of energy, relating to the conscious levels of our being, to the subconscious levels of creativity and intuition, and to superconscious levels that relate to the spiritual tendencies of the human condition” (Holden 1977, p. 5). I would classify this as a paranormal explanation.

SCIENTIFIC MISTAKES: N RAYS, POLYWATER, AND COLD FUSION

The stories of N rays, polywater, and cold fusion are classic examples of scientific mistakes. In all cases, initial claims for the existence of a new phenomenon seemed to garner impressive experimental support. Much interest was thereby generated until it became clear, on further experimentation, that the phenomena had never really existed. Once this was clear, scientists expended no further effort investigating the phenomena and these scientific dead ends were abandoned.

These stories are important for a discussion of pseudoscience and the paranormal for several reasons. First, they demonstrate once again, this time in a scientific context, that attempting to shift the burden of proof to the skeptic is not a legitimate means of defending otherwise untenable hypotheses. Second, when contrasted with claims about ESP (discussed in chapter 4), these cases show how most incorrect ideas in science are handled. Finally, they show that, under some circumstances, scientists who become strongly attached to a particular claim will resort to some of the same techniques used by proponents of pseudoscientific claims, such as nonfalsifiable hypotheses. The following discussion of N rays is based on the excellent articles by Klotz (1980) and Nye (1980). The discussion of polywater is based on the book by Franks (1981). The reader should refer to these sources for much more detail on these fascinating episodes in the history of science.

Rene Blondlot (1849–1930) bears the dubious distinction of being the “discoverer” of N rays. Blondlot was an outstanding physicist at the University of Nancy in France. He made many important contributions to physics in the late 1800s. The late 1800s and early 1900s were an exciting time in physics. In 1895 X rays had been discovered and in the next few years other types of radiation were found: alpha, beta, and gamma rays. Thus, as Klotz (1980, p. 168) points out, when Blondlot made known his discovery of N rays (named after the University of Nancy) in 1903, physics was “psychologically prepared” for the discovery of another new type of radiation. Such a discovery had, at the time, ample precedent, a precedent that it would have lacked even ten years previously.

One of the properties of N rays that Blondlot reported in his 1903 paper was that they increased the brightness of an electric spark. Blondlot used subjective judgments of spark brightness as a measure of the presence of N rays in his experiments. No instruments were used that could have given objective measures of brightness. Blondlot’s reputation in physics was such that, once he had reported N rays, other physicists rushed to study this new phenomenon. In the next few years a stream of papers appeared, largely from other French laboratories, confirming that N rays did, in fact, exist and detailing additional properties. Blondlot’s own laboratory, as might be expected, led the research effort. By this time, Blondlot had adopted a new method for determining the presence of N rays. A screen was painted with a chemical that became more luminous when N rays were projected onto it. Again, the judgments of luminosity were purely subjective; Blondlot even specified that observers should “not look directly at the screen” (Nye 1980, p. 132), but observe it out of the corner of their eye.

In the course of further investigation, it was found that the sun, flames, and incandescent objects were all sources of N rays. Another French investigator, Auguste Charpentier, found that the human nervous system emitted N rays, and this finding was soon “confirmed” in Blondlot’s laboratory. Further, when a portion of the nervous system was active, that portion was said to emit more N rays. Blondlot also discovered “secondary” sources of N rays. These were sources that absorbed N rays and then reemitted them. The fluids of the human eye were alleged to be such secondary sources and, amazingly, when the eye was exposed to N rays, it became more sensitive to dim illumination. Text that could not ordinarily be read in dim light could be read after the eye was exposed to N rays.

Here, then, was an important new phenomenon, confirmed by dozens of independent studies in many different laboratories, many of the studies conducted by well-known and highly respected scientists.

But other physicists, especially those working outside France, were skeptical about the existence of N rays. They objected to the conclusions of Blondlot and others who based their results on subjective judgments of brightness. Such judgments, which are liable to be influenced by the observer’s beliefs, are poor sources of data. One experiment allegedly showing that N rays increased visual sensitivity was faulted as being due to nothing more than dark adaptation—the phenomenon that accounts for the increase in ability to see in a dark room the longer one spends in such a room. More devastating to the claims about N rays was the failure of other physicists outside France to repeat Blondlot’s results. These failures were most striking when objective as opposed to subjective measures of brightness were used. Nye (1980) chronicles the numerous failures to replicate Blondlot’s results in the few years following his initial report.

One of the most telling pieces of evidence against the existence of N rays came in 1904, when American physicist Robert W. Wood decided to visit Blondlot’s laboratory to see for himself whether Blondlot’s experiments were valid. Wood was an extraordinary man, with many interests outside physics (Seabrook 1941). One of his interests was exposing fraudulent spiritualist mediums; Wood’s experiences in this endeavor must have helped him when he came to evaluate Blondlot’s N-ray experiments.

Blondlot had found that N rays were blocked by lead. Wood observed demonstrations of N-ray effects in Blondlot’s laboratory and concluded, as had other critics, that the reported changes in brightness that Blondlot used to argue for the reality of N rays were figments of Blondlot’s imagination and a result of his desire to validate the existence of N rays. N-ray experiments had to be carried out in a darkened laboratory so the changes in brightness due to the rays’ presence could be observed. This gave Wood an opportunity to make several observations that proved Blondlot’s judgments of brightness changes were a function of his beliefs, and not of the presence or absence of N rays. In one experiment, Wood was to block an N-ray source by inserting a sheet of lead between the source and a card with luminous paint on it. Blondlot, acting as observer, made judgments about the paint’s brightness and, therefore, about the presence or absence of N rays. Without telling Blondlot, Wood changed the experiment in one slight but vitally important way. He would indicate to Blondlot that the lead sheet was blocking the N-ray source when it really wasn’t, and vice versa. If N rays really existed, Blondlot’s judgments of the brightness of the luminous paint should be a function of whether the lead screen really was between the card and the N-ray source and should have had no relationship to whether or not he believed the sheet was blocking the source. In fact, Wood found that Blondlot’s judgments depended on whether he believed the screen to be present or not. For example, if he believed the screen was present (blocking N rays), but it wasn’t, he reported the paint to be less luminous. If he was told the screen was not present (allowing N rays to pass), but it really was, he reported the paint to be more luminous.

Similarly, in two other situations, Wood showed Blondlot’s subjective brightness judgments to be a function of his belief. Blondlot had claimed that an aluminum prism would produce a spectrum of N rays of different wavelengths, just as a glass prism produces a spectrum of visible light of different wavelengths. Wood found he could remove the aluminum prism from the path of the N rays without interfering with Blondlot’s ability to see the N-ray spectrum. Later, when Blondlot’s laboratory assistant became suspicious of Wood, Wood pretended to move the prism, while leaving it in place. This caused the assistant to report that the N-ray spectrum was not present. Finally, Wood performed a similar substitution in an experiment designed to show that N rays increased visual sensitivity in dim light. An N-ray source was placed near a subject’s eyes. The “subject of the experiment assured Wood that the hands of a clock, which were normally not clearly visible to him, became brighter and much more distinct” (Klotz 1980, p. 174) when the N-ray source was held near. Wood then replaced the N-ray source with a similarly shaped piece of wood, a substance that was not an N-ray source. Nonetheless, as long as the subject was unaware of the switch, he continued to report that objects were brighter and more distinct when the piece of wood, which he believed to be an N-ray source, was close to his eyes.

Wood’s report, published in the British journal Nature in 1904 (reprinted with a short commentary by Hines 1996), along with the failures of other laboratories to verify the existence of N rays, led to the conclusion that N rays do not exist. No further papers appeared on the topic after about 1907. Only Blondlot, convinced until the end that N rays were real, pursued his research on the topic until he died in 1930.

At the height of the debate over the existence of N rays, proponents adopted a nonfalsifiable hypothesis to account for critics’ inability to observe the rays: The critics’ eyes weren’t sensitive enough. When Wood initially told Blondlot that he couldn’t see any brightness difference on a screen when the rays were or were not present, he was told “that was because my eyes were not sensitive enough, so that proved nothing” (Seabrook 1941, p. 238). Years later, one of the early proponents of N-rays made a similar point: “If an observer (who is not convinced) sees nothing, you conclude that he does not have sensitive eyes” (Becquerel 1934, cited in Nye 1980, p. 153).

It is vital to note that Blondlot and the other proponents of N rays were not lying when they reported that they saw a brighter spark or luminous screen when they believed that N rays were present. Sparks and luminous screens vary in brightness from moment to moment for several reasons. Random changes in brightness that confirm an observer’s belief are much more likely to be noted than those that go against the belief. Numerous similar instances where a belief can profoundly change the way in which someone perceives a stimulus will be noted throughout this book.

The case of N rays also illustrates how science handles the burden of proof. (Compare this to the discussion of academic studies of ESP in chapter 4.) Assume that someone wished to argue, today, that N rays really do exist. To bolster the case, he goes back to the physics journals of 1903–1907 and assembles all the papers that argued that N rays are real. The proponent then challenges the skeptic to explain in detail what was wrong in each of the published papers favorable to the existence of N rays. Could the skeptic meet this challenge? Certainly not—there is simply not sufficient detail in the papers to pinpoint precisely what led the author to mistakenly conclude that N rays existed.

Does the fact that the skeptic cannot pinpoint the methodological errors in each and every experiment supporting the existence of N rays mean that the existence of the rays should be accepted? Of course not. The general explanation for the favorable results—such as reliance on subjective measures—along with the failure of well-designed studies to validate the existence of N rays is more than enough to justify the conclusion that N rays do not exist. Unlike proponents of pseudoscientific claims, science places the burden of proof on the individuals who make extraordinary claims. Blondlot and his colleagues failed to provide valid evidence for the existence of N rays.

Polywater, initially known as anomalous water, was “discovered” in the early 1960s by a Russian scientist named Nikdlai Fedyakin, working at a laboratory about one hundred miles from Moscow. This form of water had several extremely strange qualities. It boiled at a temperature well above water’s normal boiling point and froze at a point well below water’s normal freezing point. Further, polywater was said to be a more stable form of the H2O molecule. This led to at least one scientist making the dire prediction that, if even the smallest amount of polywater was allowed to contaminate natural water supplies, natural water molecules would spontaneously change into the more stable polywater form, thus ending all life on earth due to the radically different characteristics of polywater. (Readers familiar with the work of Kurt Vonnegut Jr. will recognize at once the similarity between polywater and the mythical substance “ice nine” created in Vonnegut’s story “Cat’s Cradle.”)

Russian research on polywater quickly moved from the provinces to a prestigious laboratory in Moscow. At first polywater attracted little attention in Western scientific circles. When it did, however, there was an explosion of papers on the topic in numerous scientific journals. Between 1962 and 1975 several hundred papers on polywater appeared.

For various technical reasons, polywater could be produced only in minute quantities inside sealed glass tubes with equally minute diameters. The debate over the existence of polywater turned on one crucial point—whether the water produced in these tubes was pure H2O, or whether it was impure, the impurities leaching out of the glass and changing the properties of the pure water. Proponents of polywater claimed they had produced pure polywater, with no impurities. That is, the substance was pure H2O in a new and different molecular configuration. Skeptics who tried to produce polywater in their laboratories consistently ended up with nothing more than impure water of the normal molecular configuration. The proponents responded that the reason the skeptics couldn’t produce true polywater was that they hadn’t learned how to do it just right. While such a rejoinder was appropriate at first, it quickly became little more than a nonfalsifiable hypothesis that proponents used to explain away every failure by the skeptics to produce “true” polywater.

As the 1960s faded into the 1970s, it became clear that polywater did not exist and claims for its reality were, in fact, based on impure water, as the skeptics had argued from the first. By the mid-1970s polywater was a dead issue.

The similarities between the N-ray and polywater episodes are instructive. One striking similarity was the use by proponents of both phenomena of nonfalsifiable hypotheses in the defense of their claims. Thus, such techniques for defending untenable claims are not limited to pseudosciences and the paranormal. They appear in legitimate science in those—happily rather rare—situations where commitment to the reality of a certain phenomenon is stronger than the data on which that commitment is based. The much more common use of nonfalsifiable hypotheses in pseudosciences and the paranormal is due simply to the near-total lack of real phenomena in these areas to begin with.

As was the case with N rays, it would probably be impossible to pinpoint the exact procedural errors made in every experiment that seemed to produce evidence of polywater. We know, of course, the general nature of the errors made, but that is different from an exact explanation for every case on record. However, as in the case of N rays (and as will be noted again in the chapters on UFOs and ESP), it is not necessary for the skeptic to explain away every seemingly positive instance of a claimed phenomenon before rejecting the phenomenon. In the polywater case, as well as in the case of N rays, the total failure of careful experimentation to turn up evidence for the reality of the phenomenon, combined with a general explanation for what went wrong, was more than sufficient for scientists to reject the existence of the phenomenon.

The same principle of rejecting a finding even if no scientific flaw can be found in the experiment, on the ground that the result cannot be replicated, is universal in science. Science is littered with experiments reporting some particular result that, upon later attempts, fails to replicate.

A personal example makes the point. My master’s thesis (Hines 1976) examined a particular question in the field of hemispheric asymmetries in the human brain. In one of the experiments, I obtained the results that I predicted. I was quite excited by this. Then I went back and tried to replicate the findings. Two replications failed. To this day I have no idea why the initial experiment succeeded in providing the anticipated results. However, the two failures to replicate, along with similar failures that were later reported in the literature, convinced me that the initial positive result was incorrect.

In the cases of N Rays and polywater, one can not specify the exact date on which these aberrations came to the attention of the scientific community, much less the public at large. Such is not the case with cold fusion, the final scientific mistake to be considered here. On Thursday, March 23, 1989, chemists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann held a news conference at the University of Utah that was widely covered on the national news programs that evening. They announced that they had discovered a method for producing nuclear fusion using simple equipment at room temperature. The term “cold fusion” was immediately coined to describe this phenomenon. Over the next few years great controversy raged over whether or not cold fusion was real or illusory. The history of the controversy has been examined in detail in three books (Close 1991; Huizenga 1992; Taubes 1993). Of the three, that by Gary Taubes’s is probably the most comprehensive. Rothman (1989–90) has published an article-length summary.

Nuclear fusion occurs when atomic nuclei are brought so close together that they stick to each other. The mass of the stuck-together nuclei is less than that of the separate individual nuclei. The “extra” mass is converted into energy, with the amount of energy determined by Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2, where E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light. Since c2 is a huge number, even a very small mass, such as that of atomic nuclei, will result in the release of a great amount of energy.

If this was all there was to it, fusion would be easy. However, in order to get atomic nuclei close enough to actually fuse, the natural repulsive force that exists between nuclei when they are brought close together must be overcome. This takes a huge amount of energy. The conventional method of achieving fusion is to use heat on the order of hundreds of millions of degrees to sufficiently speed up the nuclei so that the repulsive forces will be overcome. Needless to say, this is both difficult and expensive. Still, since fusion would be a relatively clean source of energy (it produces little of the radioactive waste that nuclear fission does), it has been the object of considerable research funds. Given the clean nature of fusion energy and the great expense of obtaining it using the conventional superheated methods, one can understand how attractive a method would be for obtaining this sort energy using cheap apparatus at room temperature. This is exactly what Pons and Fleischmann claimed to have done at their news conference.

The news conference immediately raised suspicions on the part of many scientists. The absolutely standard way to announce a new scientific result is to first publish it in a professional scientific journal in the relevant field. Before a paper can be published in such a journal, it is usually carefully reviewed by other scientists who are experts in the area of research the paper concerns. These experts point out any flaws in the paper in terms of methodology, statistical analysis, citation of the relevant scientific literature, and the like. Only after a paper has passed this type of scrutiny, called peer review, will it be accepted for publication and finally published. Peer review is one major, but certainly not foolproof, guard against the publication of the results of scientific mistakes and faulty experiment. The time to hold the news conference is after the paper has actually been published and it is generally considered unethical to “go public” with one’s results before publication, let alone before even submitting a paper to a journal, which Pons and Fleischmann had done.

What did Pons and Fleischmann point to at their news conference that led them to argue that they had actually achieved cold fusion? There were two measures that led them to the conclusion that fusion was taking place in their small fusion “cells,” which were really little more than large jars that held electrodes of palladium or platinum in a bath of heavy water (D2O). One was heat. It was claimed that the cells produced more heat than would be expected if no fusion was occurring. The other measure was gamma rays. Fusion produces gamma rays and Pons and Fleischmann claimed to have found gamma rays, coming from their fusion cells. One might think that it is an easy matter to measure these two variables, especially heat. One would be wrong. Both variables require very sensitive measurement requiring much experience. Scientists with real experience in the measurement of these two variables in the conditions under which Pons and Fleischmann were operating were nuclear physicists. Pons and Fleischmann, as chemists, had relatively little experience with such measurements. Working outside one’s area of specialization can be dangerous, because one will probably be less aware of the subtleties and pitfalls of experimentation and measurement in a field in which one is not an expert. The history of parapsychology, for example, is littered with scientists respected in their own fields who embarrassed themselves by making blunders when they assumed, incorrectly, that they were also experts in other areas of experimentation.

Pons and Fleischmann’s unfamiliarity with measurement of gamma rays is one striking example of how they went wrong. Fusion should result in gamma rays with an energy of 2,224 KeV (thousand electron volts). Pons and Fleischmann did claim to measure gamma rays being emitted by their cold fusion cells, but in the media and at scientific talks they gave, they reported the gamma rays to have an energy of about 2,500 KeV. This is a major discrepancy—but Pons and Fleischmann were not aware of it. In general, chemists didn’t spot the problem, but physicists did. The initial reports of gamma rays at 2,500 KeV were made before Pons and Fleischmann (1989) published their first report of their findings. The problem had certainly been pointed out to them before their paper was published. When their paper actually appeared in print, an amazing thing had happened. The paper reported gamma rays at 2,224 KeV, and there was no indication in that paper that gamma rays at 2,500 KeV had ever been detected. Other changes in the data took place between the verbal and the media presentations and the published paper. The reasons for these changes are still not clear, but it is difficult to interpret them charitably.

A second factor that caused scientists to be suspicious of Pons and Fleischmann’s claims at the news conference was the fact that if the claims of cold fusion were true, several basic laws of physics would have been in jeopardy. Recalling that extraordinary claims demand extraordinary proof, it was obviously going to take more than claims unsubstantiated by published results to convince scientists that cold fusion had been demonstrated. However, since the apparatus used was relatively straightforward and was visible in the background in a videotape shown at the news conference, and since Pons and Fleischmann did give a general description of their basic method, for the next several months numerous laboratories around the world tried to replicate the results.

When groups of researchers attempt to replicate an exciting new finding, even if that finding is artifactual, some will “succeed” in the replication, while some will correctly fail to replicate. The seeming successes may be due to various types of errors of experimentation. In the heated atmosphere of the first few months following Pons and Fleischmann’s news conference, it was the allegedly successful replications that got the lion’s share of attention, both from the popular media and from Pons and Fleischmann, who tended to dismiss failures as being due to “not doing it right.” Alas, they failed to be explicit about what “doing it right” consisted of in terms of exact methodology. As time passed, it was established that the seemingly successful replications were due to various sources of errors, some quite subtle. When these sources of error were eliminated, so, too, was evidence for cold fusion. Close (1991) discusses many of these replications and shows what went wrong to mislead the researchers into thinking that they had obtained fusion.

One laboratory in particular seemed to be especially able to replicate Pons and Fleischmann’s findings of excess heat in their fusion cells—and to find tritium as well. Standard physical theory requires that tritium be produced as a result of fusion. Pons and Fleischmann had never reported finding any tritium, but tritium, as well as heat, was reported in cold fusion cells in the laboratory of John Bockris at Texas A & M University. The combined finding of tritium and heat was taken as strong support for the reality of cold fusion. Alas, the tritium appeared only sporadically and, like other cold fusion findings, could not be reproduced. The actual pattern of the appearance of tritium suggested the possibility that it was fraudulently being added to some cold fusion cells (Taubes 1993).

The finding of excess heat in the fusion cells in Bockris’s lab has a particularly interesting explanation. It is a perfect example of how disregard for the basic rules of scientific evidence kept the cold fusion debate going. Even in the total absence of cold fusion, sometimes a cold fusion cell would run a little hotter than expected, while others would run slightly cooler. That is, not each and every cell would be at exactly the same temperature. The temperature of the cells taken as a group would vary around some average. Cells running cooler than expected were negative results, and Bockris wasn’t interested in negative results, which he said “can be obtained without skill and experience” (quoted in Taubes 1993, p. 322). Such negative results were simply tossed in a drawer and not considered. When a cell ran slightly warmer than expected, this was taken as evidence for cold fusion.

N rays and polywater died fairly quiet deaths once the scientific community realized the nature of the flaws in the experiments said to support these phenomena. And neither had any following among the general public. Such is not the case with cold fusion. Disgraced in the eyes of the scientific community (Fig. 2), Pons left the academic world and in 1992 to work for a private industrial concern still looking for evidence of cold fusion. The Japanese Ministry of Trade and Industry continued to support cold fusion work for a few years in the mid-1990s. But the attention the media gave cold fusion ensures that it will live on forever, supported by a small group of true believers who will always insist that the ultimate proof of cold fusion is just around the corner, with that one more crucial experiment that has to be done.

CONSPIRACY THEORIES

While conspiracy theories are not necessarily pseudoscientific or paranormal in nature, they do pop up in the belief systems of many proponents of these claims. The best known example, which will be discussed in chapter 8, is the belief that a vast government conspiracy exists that has kept the real evidence for the extraterrestrial nature of UFOs hidden from the public for the past fifty years or so. In the alternative medicine movement, it is sometimes believed that another conspiracy exists, this time between the government and the drug companies, to keep news of effective treatments for cancer and other dreaded diseases from the public. In general, whether they concern pseudoscientific or paranormal topics or not, the conspiracy theory belief systems do share a major component with the belief systems of other pseudoscientific proponents: their inherent nonfalsiflability. When the alleged evidence for a particular conspiracy has been refuted, the proponent will often point to the very lack of evidence for the theory as evidence for the theory! That is, it is argued that the lack of evidence is not because the theory is false, but instead is due to the supreme effectiveness of the conspiracy itself in seeing to it that no convincing evidence for the conspiracy can be found. In this sort of cloudcuckooland, any belief, no matter how absurd, can be sustained for a very long time indeed.

Since the topic of this book is specifically pseudoscientific and paranormal claims, it would not be appropriate to devote much space to conspiracy theories outside of these areas. However, let me simply make brief note of several excellent works critically examining two of the most well known nonparanormal conspiracy theories, those holding that the Holocaust never happened and that President Kennedy was not killed by a single gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald. Lipstadt (1993) has written a chilling book on the Holocaust denial movement and Shermer (1994) has discussed the factual errors in the claims of the deniers. Posner (1993), in an extremely detailed treatment, discusses the problems with the various claims of a vast conspiracy to kill Kennedy. As is the case with any conspiracy theory, the Kennedy theory requires that a huge number of people be part of the conspiracy and that none of them come forward. Our experience with real conspiracies, such as those underlying Watergate, the Pentagon Papers, and the bombing of Cambodia, show that it is essentially impossible for operations involving very many people to stay secret for long. Gerlich (1998) has written an article discussing some of the specific issues raised by the JFK “conspiracists.” Finally, Pipes (1997) has written a fascinating history of conspiracy theories. I found his discussion of the Freemasons and the Illuminati, two groups conspiracy theorists have loved to hate for centuries, especially interesting. He also provides an excellent history of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an antisemitic fraud produced by the Czar’s secret police and first published in 1903.

WHY STUDY PSEUDOSCIENTIFIC CLAIMS?

The serious examination of pseudoscientific and paranormal claims by scientists and scholars who are skeptical about the existence of such phenomena is not a recent development. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the claims of spiritualists were carefully scrutinized by several scientists (see chapter 2). A new interest in evaluating pseudoscientific claims arose during the early 1970s as scientists and educators became concerned with the publics’s uncritical acceptance of almost every type of pseudoscientific claim. This resulted in the formation in 1976 of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP). The members of CSICOP, including scientists, writers, educators, journalists, and philosophers, founded the organization because of the concern about the “uncritical acceptance by wide sections of the public of many claims of ‘paranormal’ phenomena as true, even without testing” (Kurtz 1976–77, p. 6). The objectives of CSICOP include critical, unbiased, objective research into pseudoscientific claims; the publication of the results of these studies; and a commitment not “to reject on a priori grounds, antecedent to inquiry, any or all [paranormal] claims, but rather to examine them openly, completely, objectively, and carefully” (Kurtz 1976–77, p. 6).

This is very different from the usual approach of scientists and scholars, whose typical response to pseudoscientific claims is simply to dismiss them as nonsense. This latter is a most unfortunate attitude. It is important to examine these claims objectively for at least four reasons. First, the claim may, in fact, be true. Failure to examine it would then delay the acquisition of new, perhaps important, knowledge. Second, if the claim is false, the scientific community, which is heavily supported by the public through taxes, has a responsibility to inform the public. Ignoring a claim and not testing it leaves the field to the promoters of such claims and deprives the public of the information needed to make informed choices. Third, several important psychological issues relate to the study of pseudoscience and the paranormal. Why, for example, do people so strongly believe in theories that not only have no evidence to support them but also have been shown time and again to be flat wrong? Fourth, and finally, the unthinking acceptance of pseudoscientific claims poses real dangers. Believers may act on their beliefs and cause physical harm, even death, to themselves and others. In addition, as our society becomes more dependent on science and technology, we are all threatened by an increase in the uncritical acceptance of clearly incorrect, nonscientific superstitions and related beliefs. The rest of this section will consider in detail these reasons for the study of pseudoscientific claims.

The Claims Might Be True

There are several examples in the history of science of phenomena that were once considered to be pseudoscientific or paranormal in nature but were eventually shown to be real, verifiable phenomena of considerable theoretical and practical interest and importance. Perhaps the best example is hypnotism. Hypnotism was first called “mesmerism” after the Viennese physician Franz Anton Mesmer who popularized it in the 1700s. Mesmerism, with its talk of animal magnetism, was clearly a sham (see pp. 374–75), but it did lead to the development of hypnosis, which gained some respectability in the late nineteenth century through its use in psychotherapy. In the twentieth century, especially in the recent decades, the scientific study of hypnosis has expanded greatly. There are now several journals and many books devoted to the topic. As is frequently the case when a pseudoscientific phenomenon is studied carefully and shown to represent a real phenomenon, some initial claims for the phenomenon are found to have been overstated. This is certainly the case with hypnosis, as will be seen in chapter 8. The point here, however, is that there is a true hypnotic phenomenon that is well deserving of study (Nash 2001).

A second example of a phenomenon once scorned but then studied and confirmed scientifically is the case of meteorites. “Stones falling from the skies? Absurd! Ridiculous!” was the common attitude well into the eighteenth century. Hall (1972) has pointed out that reports of stones falling from the skies were once treated by the scientific community with much the same contempt that is now reserved for reports of UFOs. Yet meteorites are clearly real. Might UFOs be real, too? To find out, one has to study the phenomenon, not just dogmatically insist that it is “impossible.”

A final example is acupuncture, the ancient Chinese technique for reducing pain that gained considerable Western attention after then—President Nixon renewed relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China in the early 1970s. The first reports of this technique certainly sounded unlikely—after all, how could sticking needles in someone reduce his perception of pain? However, experimental work since the early 1970s has suggested that acupuncture for the relief of pain may be a real phenomenon, (pp. 377–78) although again, initial reports of its effectiveness were rather exaggerated.

In all of these examples, phenomena that were initially considered to be pseudoscientific and unworthy of study have been shown to have some basis. These cases alone would justify the study of other pseudoscientific and paranormal phenomena, although it must be realized that the “hit rate” in this type of endeavor is very low. Of the numerous paranormal claims considered in the remainder of this book, the vast majority will be found to have no scientific support.

Responsibility to Inform the Public about the Truth of Paranormal Claims

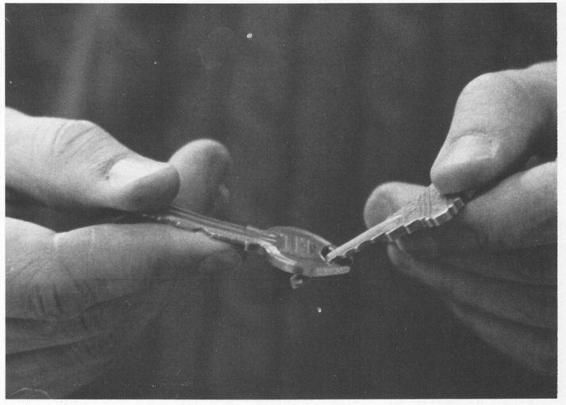

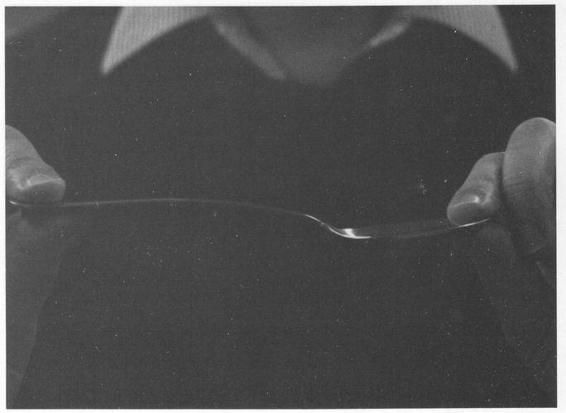

A glance at the occult books section in any moderately large bookstore is all that is needed to convince one of the huge market for pseudoscientific and paranormal claims in this country. A 1997 poll (Nisbet 1998) found that 45 percent of Americans believe in faith healing, 30 percent in UFOs, 37 percent in astrology, and 25 percent in reincarnation, to give a few results. John Mack’s (1997) book Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens was a best-seller when it was published. Every kind of pseudoscientific claim finds eager buyers. Psychics, palm readers, tarot card readers, mediums, and the like rarely lack for victims willing to shell out fifteen, twenty-five, or even one thousand dollars for a reading. Those who claim that Earth was visited in historical times by ancient astronauts, or that there is a mysterious area off Florida’s east coast where ships and planes have disappeared, or that they can bend keys with sheer mind power can make millions from books, films, and the lecture circuit. In short, the public spends a lot of time and money supporting the proponents of pseudoscience and the paranormal. As will be seen in the following chapters, there is not one bit of evidence to support these pseudoscientific claims, and much evidence exists that flatly contradicts them. This being the case, the continued claims by proponents of pseudoscience constitute nothing short of consumer fraud. And it is a massive fraud that costs the American public billions of dollars each year. In this situation, scientists have a strong responsibility to investigate pseudoscientific claims and to speak out vigorously when those claims are shown to be false. Unfortunately, communication of the real data on the truth of pseudoscientific claims is often hampered by the media. Television and radio programs and newspapers are frequently more interested in presenting sensational claims than in carefully evaluating the truth of such claims. The media, both print and electronic, have often acted with extreme irresponsibility in covering pseudoscience and the paranormal. In the case of uncritical coverage of faith healers and psychic surgeons, this lack of responsibility on the part of the media has resulted in injury and death.

The case for speaking out is even clearer in the case of modern health and nutrition quackery, now known as “alternative medicine,” which in the early 1980s was a $10-billion-a-year problem in the United States (Pepper 1984). The figure must be much higher now. The quacks’ and charlatans’ victims are most likely to be those least able to defend themselves—the desperate, the elderly, and the poor.

Only through careful evaluation of pseudoscientific claims and seeing that the results of those evaluations are reported by the popular media can the public be fully informed. The proponents of pseudoscience and the paranormal, who make vast sums of money selling their wares, are unlikely to provide the public with accurate information. Scientists, then, have a responsibility to inform the public.

Psychological Issues

Ethical issues aside, several important psychological issues are raised by the study of pseudoscience and the paranormal and people’s belief in them. The major issue is why people come to believe in such claims in the first place. What is it that convinces them, for example, that astrology is a valid method to guide their lives? Or that biorhythms really predict when they are most likely to do well or poorly on an exam? Second, why do these beliefs persist so strongly in the face of clearly contradictory evidence?

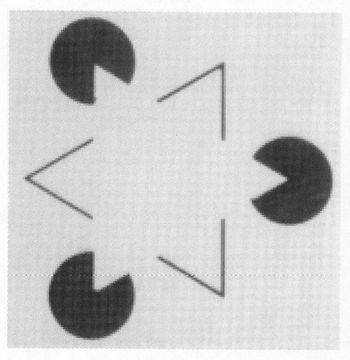

The answers to these questions will be discussed throughout the remainder of this book. Suffice it to say here that research on perception, and especially memory, has demonstrated the importance of cognitive illusions that are in many ways analogous to visual illusions. These cognitive illusions provide the basis for both initial and continued belief in pseudoscientific and paranormal claims, although other factors to be discussed are also important. Dawes (2001), Shermer (1997), and Vyse (1997) have all written book-length treatments of the psychology of belief that go into much greater detail than I am able to here. Lastly, the widespread acceptance of paranormal and pseudoscientific belief raises important sociological questions. Although these are beyond the scope of this book, Goode (2000) has discussed them in detail.

Dangers of Paranormal Beliefs

Skeptics are often asked, “Who cares if there really isn’t anything to astrology? What does it hurt if someone believes in it?” I’ve found that this question is frequently asked by proponents of pseudoscientific claims when they have been backed into a corner by the evidence. The answer can be made at three levels. At a philosophical level, most people would agree that it is harmful to hold invalid beliefs and that, generally speaking, one should base one’s life on a correct view of how the world operates. To do otherwise is to be deluded.

On a more practical and personal level, one can consider pseudoscientific and paranormal claims in the context of consumer fraud. People are being induced through false claims to spend their money—often large sums—on paranormal claims that do not deliver what they promise. Presumably no one would ask, “What’s the harm if the label says the cereal box contains sixteen ounces but it really only contains thirteen ounces?” The situation is the same for paranormal claims, except that the box is empty. The personal damage done by uncritical acceptance of paranormal claims can be most clearly seen in faith healing and psychic surgery (see chapter 10), and alternative medicine (see chapter 11). People go to these fraudulent healers and often are convinced, incorrectly, that they have been cured. Thus, they may not seek legitimate medical help. By the time they realize that they have not, in fact, been cured, they may be beyond even medical help. Nolen (1974) has documented such cases. Of all the proponents of pseudoscience, faith healers and psychic surgeons are the most dangerous—they kill people.

Finally, from the point of view of society at large, uncritical acceptance of paranormal belief systems can be extremely damaging. The classic example is the witchcraft craze that swept Europe between approximately the middle of the fourteenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries. During that period, well over two hundred thousand people were burned, tortured, or hanged as witches (Robbins 1959). The belief in the reality of witches is a classic example of a paranormal belief. It shares many characteristics with modern-day paranormal belief systems. We will see, for example, in chapters 7 and 8 that proponents of the reality of UFOs as extraterrestrial spacecraft argue that some of the strongest evidence for the reality of UFOs is the many reports of UFOs that have been seen and reported by reliable, trained, sane observers. Yet even a short perusal of the literature on witchcraft will reveal hundreds of similar reports of witches turned in by reliable, trustworthy witnesses. Of course, not one of these reports was true.

Another similarity between the belief in witchcraft and the belief in numerous modern pseudoscientific claims is the presence of an irrefutable hypothesis as a cornerstone of the belief system. For the poor individual accused of being a witch, the irrefutable hypothesis spelled a slow and lingering death. There was no possible piece of evidence that could show that the accused was not a witch. Once an accusation was made, no matter how flimsy the grounds for it, the accused was arrested. At this point, the accused was asked to confess to the charges. If the confession was not made, the accused was tortured. If a confession was still not made, the torture continued. Johannes Junius, the burgomaster of Bamberg, made this point in his last letter to his daughter before he was executed as a witch in August 1628. He described the several days of torture he endured without confessing and then says, “When at last the executioner led me back into the cell, he said to me, ‘Sir, I beg you, confess something, whether it be true or not. Invent something, for you cannot endure the torture which you will be put to; and even if you bear it all, yet you will not escape, not even if you were an earl, but one torture will follow another until you say you are a witch’” (Robbins 1959, pp. 292–93). There was no way out. If one confessed without torture to being a witch, one was executed. If one did not confess at once, one was tortured until one did—and was then executed. If one confessed and later recanted the confession, the torture started anew. To make matters worse for the accused, who might be willing to confess at once simply to escape torture, one was asked to name acquaintances who had engaged in witchcraft. If names were not forthcoming, they were extracted, again, under torture. These other individuals were then rounded up and tortured into confessing and naming, still more “witches,” and so the horrible cycle went on.

It should not be thought that in our modern and “enlightened” age, witch-hunts are a thing of the past. In the 1980s and 1990s, hysteria over bizarre claims of mass abuse and killings, usually of children, by a well-organized and highly secret group of Satan worshipers swept the United States. Innocent parents and teachers were accused and many went to jail. As in the medieval witch trials, there was no physical evidence. The victims of this modern witch-hunt were not convicted on the basis of testimony extracted under torture, but by something eerily similar: the testimony of children who had been subjected to interrogation techniques such that they came to truly believe the fantastic accusations they were making (chapter 12).

The medieval witch delusion also provides what is presumably one of the first reported cases of “special pleading” for a pseudoscientific claim. Proponents of pseudoscience often claim that the usual rules of science are too strict (tacitly admitting that their evidence is scientifically inadequate to prove their claims) and that less-stringent criteria of proof should be allowed for this or that pseudoscientific claim. In this vein, Robbins (1959) notes a “distinguished professor of law at the University of Toulouse [who] advocates the suspension of rules in witch trials, because ‘not one out of a million witches would be accused or punished, if regular legal procedure were followed’” (p. 34).

An even more terrible pseudoscience, the phony racial theories of the Nazis in the twentieth century, resulted in loss of life on a scale vastly greater than that caused by the witchcraft delusion. Although the role of the occult per se in the rise of Nazism has been overestimated, it is clear that the racial theories upon which Hitler built the Holocaust were pure pseudoscience.

Another commonly heard defense of paranormal claims goes like this: “Reality is relative. If I decide to believe in astrology, then it becomes real in my own reality and works for me.” In other words, belief determines the structure of reality. An extreme version of this rather silly position is held by many parapsychologists who try to explain their critics’ repeated failures to find any evidence confirming the existence of ESP by saying that the critics don’t believe the phenomenon to be real and, therefore, for the critics, it isn’t. We’ll see in chapter 4 that a much better explanation is that the critics conduct better, more tightly controlled experiments than do the believers. In any event, this position that belief determines reality puts its proponents in a rather unpleasant position. In Nazi Germany millions of people really believed that Jews were subhuman. If belief determines reality, then this belief must really have been true. This is an absurd position, and those who hold that belief determines reality have never bothered to think their notion through to the repellent consequences of its logical conclusions. The point is that truth is independent of belief. When the proponents of a pseudoscientific claim maintain that belief determines reality, it’s a safe bet that they can’t prove their point using legitimate rules of evidence.

The examples of the witch delusion and the Nazi horrors show the great damage done by the uncritical acceptance of pseudoscientific claims. Others will be encountered throughout this book. All might well have been avoided if the public had been educated in critical scientific thinking and had simply asked: “What evidence is there that what you are telling me is really true?”

Of course, not all pseudosciences have the vast potential for damage of the witch mania and the Nazi racial theories. However, if one accepts faulty evidence, intellectual shoddiness and fraud, and twisted logic in the case of relatively benign pseudosciences, it becomes much easier to accept the same type of evidence when it is presented in support of much more damaging pseudosciences.

Chapter 2

PSYCHICS AND PSYCHIC PHENOMENA

The term “psychic phenomena” conjures up an image of Jeane Dixon foretelling the future with great accuracy, of a psychic crime fighter leading police straight to where a body has been hidden, of a spiritualistic medium like John Edward contacting the dead and relaying to the living information only the dead could have known, or of an ordinary individual having a dream that later turns out to have correctly predicted an important event. This chapter will discuss the origins of spiritualism and examine contemporary claims for such phenomena. The somewhat more scientifically respectable study of ESP, clairvoyance, and psychokinesis in parapsychological laboratories will be discussed in chapter 4, which will also discuss the well-known psychic Uri Geller, as his alleged abilities have been extensively tested in parapsychological laboratories. That Geller could equally well have been discussed in the present chapter points up the often fuzzy distinction between spectacular psychic claims and laboratory parapsychology.

SPIRITUALISM

Scientific investigation of alleged psychic phenomena began in the mid-1800s as a result of the worldwide interest in spiritualism. Spiritualism was born in 1848 in the small New York town of Hydesville, about twenty-five miles southeast of Rochester. Two sisters, Kate and Margaret Fox (eleven and thirteen years old, respectively), produced strange knocks and rapping in their home, which were interpreted as messages from the dead. The effects were produced by various simple tricks, as the sisters later admitted (Kurtz 1985b; Brandon 1983). An older sister took the young girls on tour, and a nationwide interest in spiritualism and communication with the dead sprang up in their wake. This interest quickly spread overseas. As interest in spiritualism grew, so did the number of spiritualistic mediums, individuals who claimed to be able to contact the spirit world and communicate with the dead. Mediums could be found in every city.

Communication with the dead took place at a seance, in which the medium and “sitters” would hold hands while seated around a table in the dark. Various phenomena occurred during the seance, varying from rather mundane rappings and knockings, through table tipping (in which the table seemed to move of its own accord), up to the most spectacular seances where “ectoplasm” would flow from the medium’s body, “actual spirits” would appear, and objects would materialize out of thin air, presumably “apported” from the spirit world. Photographs of disembodied spirits floating near mediums were also produced in some quantity. It was these sorts of phenomena that convinced so many people of the truth of spiritualists’ claims and of the reality of communication with the dead.

The rage for spiritualism attracted the attention of some of the period’s leading scientists. Most were highly skeptical and critical of spiritualism, but several attended seances and came away convinced of the reality of spiritualistic phenomena. A few then instituted often impressive studies of individual spiritualists which, they claimed, gave solid scientific support to the claims of spiritualism. This type of research and interest led to the founding in England in 1882 of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). The goal of the SPR was scientific investigation of spiritualistic and other “psychic” phenomena. As such, it represented an alliance between the spiritualists and the small portion of the scientific community that accepted their claims. As time passed, however, the alliance weakened and finally split. The split came about not because of doubt on the part of the scientists who belonged to the SPR, but because of a fundamental difference with spiritualists over the correct interpretation of the phenomena that took place at seances (Cerello 1982).

The spiritualists felt that these phenomena proved the existence of an afterlife and the reality of the individual soul, and demonstrated that they were in communication with the dead. For the spiritualists, these claims did not have any particular religious implications and hence spiritualists were attacked as vehemently by organized religion as by organized science, perhaps more so. Their claims, however, were still too non-materialistic for many of the scientists in the SPR. As Cerello (1982) points out in his excellent history of the development of psychical research in Britain during this period, the SPR came more and more to interpret spiritualistic phenomena in terms of telepathy (what would now be termed ESP) and psychokinesis (PK). Thus, if a medium told someone at a seance something that medium could not have known through normal channels, she (most mediums were female) was not getting the information from the spirits of the dead, but rather through her own power of ESP. Similarly, when an object was apported during a seance, it was not being transported from the “other side” by spirits, but was being moved by the medium through PK. This latter explanation for spiritualistic phenomena prevailed in the SPR, and is still accepted in parapsychological research to this day. Thus, these phenomena constitute the first pieces of evidence for the reality of paranormal claims. It is the nature of this evidence that will be considered here.

The debate over the validity of spiritualistic phenomena, however they were interpreted, raged well into the early twentieth century. Some of the most famous names in science, literature, and the arts were involved, including Michael Faraday, the discoverer of electromagnetism; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; and magician Harry Houdini. Brandon (1983) has written an excellent account of the history of spiritualism and the debate surrounding it. (Modern spiritualists, who still exist and who still claim to be in communication with the dead, will be considered later in this book.) Much of the material in the following sections is drawn from Ray Hyman’s (1985a) “A Critical Historical Overview of Parapsychology.”