Tristan Bancks

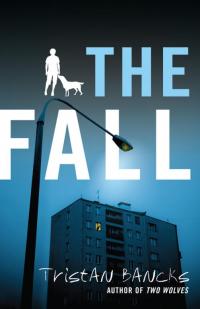

THE FALL

For Hux

ONE

THE FALL

I woke to the sound of a voice pleading, high-pitched and urgent. I listened with my whole body. The man’s voice was coming from the apartment above. Or was it below? I couldn’t be sure. In the six days I’d been staying with my father I hadn’t heard much noise from the other apartments.

The microwave in the kitchenette read 2.08 am. My father had left the heaters on too warm again so my head was fuzzy and my throat was dead dry.

I sat up and the springs on the sofa bed squeaked. There were footsteps across the floor above now, and another man’s voice, low and threatening. I rolled off the couch, grabbed my crutches and stumbled to the wide window. I wiped the foggy glass with the palm of my hand, my bruised armpits resting painfully on the hard rubber crutch-tops. I looked out through the branches of a tall, leafless tree and across a yard to a wire fence and a mess of railway tracks beyond.

It was raining lightly. People said that winter had come early to the city this year but in the Mountains, where I lived with Mum, it was much colder than this already. I twisted the old latch and squawked the window open a little, pulling it in towards me. I put my ear to the narrow opening and was struck in the face by a rectangle of cold.

I listened.

The men’s voices sounded louder now but I still couldn’t make out what they were saying. I opened the window a little more, stuck my head out and looked up and to my left. I could see someone’s fingers curled over a balcony railing. All of the apartments had balconies but they didn’t hang out over the edge. They were set into the building next to the rear windows. That’s where the voices were coming from. The man who was pleading sounded small and thin, like a jockey. Another man was rough and phlegmy like he had crunchy gravel caught in his throat. He sounded stubborn, bullish, like Mr Mawson, my science teacher.

Something bumped my leg. I pulled my head back inside and looked down to see Magic, my father’s dog. My parents split up before I was born so Mum got me and my dad got Magic. Some days Mum acted like she got a raw deal. That’s why she called my father ‘The Magic Thief’. And for other reasons, I suspected.

Magic shook her head from side to side, her long ears slapping loudly against the top and sides of her head.

‘Shhhhh, girl,’ I whispered, rubbing one of those silky, soft ears for comfort. Magic was the oldest, fattest, brownest dog in the world. Also, the funniest. I had spent more time with her this week than I had with my dad.

On the balcony upstairs, the men’s argument intensified. I listened hard but the wind and rain seemed to dampen their voices. I thought about waking my father but I wasn’t sure Harry would appreciate it. That’s what he liked to be called – ‘Harry’. Never ‘Dad’.

The bigger-sounding guy coughed hard then spat over the balcony. The little guy raised his voice. One of them must have slammed against the railing or a door or wall. I could feel the impact through the window frame. I squeezed Magic’s ear hard with my free hand and she yelped quietly.

‘Sorry,’ I whispered.

I wanted to drink in every detail, like my father would when he was out covering a story. I turned to the microwave. It was 2.11 am. The small man screamed but the voice was quickly stifled, maybe by a hand. I turned back just in time to see a flash of black as something fell past my window.

Someone.

He flapped his arms and clawed at the air, trying desperately to hold onto something. He let out a strangled yawp as he fell.

Pushed was my immediate thought. He didn’t just fall. He was pushed.

I heard the impact and stared down through the gnarled tree branches at the body lying facedown in the mud beside the bin shed.

The body.

I was almost thirteen years old and I had never seen a dead human being before. At least, I figured the man must be dead. It’s further than you think, six storeys. He lay there, his body buckled, a crumpled mess of limbs, lit by a single railway security light on a pole at the edge of the train tracks. I wished that I hadn’t seen it. Now I couldn’t ‘unsee’ it. I felt like this image would be scorched into my brain forever. I wished I hadn’t begged to come to my father’s in the first place, and that I hadn’t behaved so badly that my mother had finally agreed.

A siren cut through the constant hum of traffic noise. Next came footsteps on the floor above, then the distant squeal of an apartment door. I turned and crutched across the seagrass matting to the bedroom, swinging my legs forward then reaching ahead with the crutches, not even feeling the pain in my armpits now.

‘Harry,’ I whispered.

No response.

‘Harry!’

I went to his bedside and shook the rumpled quilt but it gave way. I pulled the quilt back. My panic deepened. I fumbled for the lamp switch and flicked it on.

There was no one in the room but me.

TWO

ALONE

I heard the rattle of the old lift climbing upwards, past our apartment, then the low thunk of it arriving on the sixth floor. I listened intently as the doors opened, closed and the lift clattered down again. I could imagine the scene in one of my comics: the large, dark shape of the man seen through the crisscross wire mesh window of the lift door.

I twisted awkwardly and crutched out of the bedroom to the bathroom door, which was open just a crack.

‘Harry?’

I shoved the door with the bottom of my crutch. Every nerve in my body lit up. The room was empty and dead dark, no windows. I flicked the dull light on, revealing old blue tiles, mouldy shower curtain, cracked mirror and the rust stain on the bath from the tap that would not stop dripping. But no Harry. I switched off the light.

It was a small, shabby one-bedroom apartment – a lounge room, sparsely furnished, with a crusty old kitchenette and noisy fridge on one wall, then the bedroom, bathroom and a small balcony. I slept in the lounge room. The front door led to the lift and stairs. There was nowhere else that my father could have been.

I headed back across the lounge room towards the window, whacking my right knee on the edge of the sofa bed and sending 50,000 volts of pain surging through my body. I swallowed a scream and squeezed the bandage on my knee, just above where they’d cut me open and inserted six large metal staples ten days ago. I dug my fingers in hard and stayed there, hunched over my pain in the darkness, thinking about my dad and trying not to cry.

Once the electric agony had softened to a dull throb, I stood and struggled back to the window, edging an eye out over the ledge. I looked down through the crooked, leafless branches and saw the shape there – a man twisted up like a pretzel, rain falling on his body. He did not move. I wanted to call out to the other people in the building. I wanted to scream loud enough to wake the people in the skyscrapers studded with lights on the far side of the railway tracks and beyond the old railway sheds, but something told me not to.

The man who fell was not my father. I repeated it again and again, making it true.

Text Mum, I thought.

I had no call credit till the start of the new month but I still had unlimited texts. I ran out of call credit and data my first day at Harry’s. There was no landline in the apartment. Only Harry’s mobile. It was locked with a code, which I had unsuccessfully tried to crack. No wi-fi either. There were forty-seven different wi-fi signals available from other apartments and shops but every single one of them was locked.

Harry had only lived here for about a month. He said he didn’t plan on being here long, that it wasn’t worth getting the web connected and that I could do better things with my time than stare at a screen. He said he was a Luddite, which meant he was allergic to technology. He used it only when necessary. But I don’t think he understood the seriousness of the situation. Kids can die from wi-fi starvation.

Mum said Harry only ever lived anywhere for a few weeks or months before he moved on. She called him ‘itinerant’. I was pretty sure it wasn’t a compliment. Texting her now would only confirm her belief that my dad was a hopeless, irresponsible little man.

I’ll just pop out and grab some milk. I’ll only be a minute. You go off to sleep. It’s late.

That’s what he’d said. Milk. And now he was gone. But he couldn’t be gone. Fathers don’t just disappear. Especially fathers who you barely knew, had barely had a chance to know.

I tried not to see newspaper headlines with his name in them. I went to the sofa bed and pulled my backpack out from underneath. I took my phone from the front zip pocket and texted my dad. I knew it wasn’t worth it but I tried anyway.

WHERE R U?

I heard a bing from Harry’s bedroom. He only sometimes took his phone with him. He said it was too easy to track, that phone tower records could be used in court and crime reporters like him were being sprung for meeting with criminals and forced to dob in their best contacts.

I wanted to turn on a lamp for comfort but I stopped myself. I didn’t want anyone to know that someone was awake in this apartment. There was enough city light pouring in through the window for me to get around. Night-time in the Mountains was pitch-black with millions of stars but the city sky on a cloudy night seemed almost as bright as day.

I moved slowly, quietly to the window again and pushed it open a little more. When I saw what was down there, my breath froze in my throat. There was a large black umbrella. Someone was standing over the body. I flicked my phone to camera. Gather details. That’s what Harry Garner would do when he was out on a story. I wondered if he was a crime reporter because he loved details, or if he loved details because he was a crime reporter.

As I reached out the window, in my excitement I knocked the phone hard against the timber window frame, making a loud clunk. The umbrella shifted to the side and the shape beneath it looked up, directly at me. He was larger than I had thought. Even from up here he looked big. An elephant of a man. His face was white and round as the moon. His hair was silver and his eyes were lit up by the security lamp. I stepped back from the window onto my bad leg, pressing my hand hard against my mouth.

What have I done? Why did I look? I had seen everything and the man knew it.

I’d never met a murderer but I figured they probably didn’t like it much when they realised that someone had seen them committing their crime and then tried to take photos of them standing over the body.

He would come up here. I had to go.

The stairs. Harry had told me to always use the stairs. And the man had used the lift. I could go to the police station. I had seen one on the street when I arrived. Or I could go to the convenience store across the road. It would be open.

I pulled a pair of shorts on over my boxers. As I threw my phone into my backpack, I saw Harry’s laptop sitting on the dining table. He worked on it constantly when he was home. He would want me to take it with me. I put it in my bag too. As I shouldered the backpack an electricity bill fluttered from the table to the floor. I left it, crutching quickly towards the front door.

Clink-screek. A sound from the ground below. The man escaping? Or coming upstairs?

‘Magic, come,’ I whispered.

She lumbered across the seagrass matting, thrilled to be going for a walk.

THREE

DOWN

I eased my way, barefoot, down the creaky timber staircase. The cold wood bit the sole of my left foot each time it made contact with the stairs. I hadn’t crutched downstairs much. Tina, my favourite nurse at the hospital, had taught me on the fire exit just outside the ward. I tried to remember what she had said. Crutches first, then left foot, always keeping my right foot raised and out of harm’s way. If you swung your feet out first you could pole-vault down five or six stairs. Believe me. I knew.

I held tight to the crutch and Magic’s lead with my left hand to stop the 42-kilogram dog from losing her footing and shooting down the stairs like a furry torpedo and taking me with her. The collar pressing on Magic’s throat turned her noisy breathing into something like a bowsaw cutting down a thick gum tree.

The staircase smelt like mould and was lit by a cold, fluorescent strip light on each landing. There were two flights of stairs between each floor. Magic and I slowly weaved our way down.

‘Shhhhhh,’ I whispered to the noisy breather. I doubted that Magic had ever been walked in the thirteen years since my parents broke up. She didn’t even go outside to wee and poo, which, in my opinion, must be humiliating for a dog. She had a small doggy litter box in the bathroom and she didn’t like me watching her while she used it. In the time that I had been staying at Harry’s apartment, I had seen him feed Magic chocolate-chip biscuits, a whole banana, spaghetti bolognaise and half an extra-spicy Thai chicken pizza. So Magic’s weight and breathing problems weren’t a total mystery.

As we passed the two apartment doors on the third-floor landing I paused to listen, to make sure the man who had been standing over the body wasn’t using the staircase. I stared at 3A and 3B, wondering if either of them was unlocked. I thought about knocking and asking for help but my father had told me I wasn’t allowed to speak to anyone in the building. Harry was gone now, though, so why should I care about his stupid rules? The thought that he had left me alone in the apartment in the middle of the night made me angry. He had been upset with me before he left just after 10 pm – he hadn’t yelled or anything but I knew. I waited up for a bit but must have fallen asleep.

I’ll only be a minute. You go off to sleep. It’s late.

I could feel the wire coil of rage in my chest start to heat. That coil made me do stupid things. That coil was why I was here at Harry’s, why my mother had finally given up and sent me here after years of me badgering her. I tried to breathe, to stop it from glowing red.

Harry didn’t mean to stay out. He’s a good person. There must be a good reason.

‘You can’t be seen going in or out of the apartment. In fact I’d rather you didn’t go out on your own at all.’ That’s what he had said on the first morning.

‘Why?’ I’d asked.

‘A story I’m working on, something I’m involved with. I can’t go into it right now, but it’s important that you listen to me, okay?’

I had nodded.

‘Only the stairs, Sam. You promise me?’

At first I thought it was a bit harsh, him not letting me use the lift when I was on crutches. But then I realised that he was trusting me with his secret. I had no idea what that secret was but it still felt good to know that I had a role to play. I didn’t like the idea of crutching down all those stairs so I had spent the past six days inside: watching TV, playing my Xbox, writing a new comic book, trying to avoid the schoolwork Mum had made me bring and, at night, monitoring my father, trying to find out about the story he was working on.

A month ago I overheard Mum on the phone in her bedroom. She sounded kind of weird so I went to the door and listened. I realised that she was speaking to Harry, asking if I could come stay for a week after my operation. I sat in the hallway, back against the wall outside Mum’s room, and listened to their conversation. She only spoke to Harry every couple of years as far as I knew, usually about money. He was a little bit late in his child support payments. Nine years.

The last time Harry was in my life I was still in my mother’s belly so I don’t remember him too well. Mum never mentioned him and he wasn’t exactly trying to kidnap me to get custody. I think Mum thought I’d be better off without him. But this time, she was stuck. She couldn’t afford to take time off while I was home after the operation and she wasn’t leaving me alone to get into more trouble. She kept saying that she was ‘over it’. Over me.

When she was on the phone to Harry she said, ‘This past year he’s been behaving so out of character. He’s been just like you. Impulsive. Never thinking of anyone else but himself, like the universe revolves around him. You need to get involved in his life. Speak to him. At least show him what happens to selfish, inconsiderate people when they get old.’

Harry had said something then. It may have been ‘thanks’ or something more aggressive.

‘He needs a father,’ Mum told him. ‘A male role model.’

Harry argued – I could hear him raise his voice – and Mum told him to step up and be a man. ‘Grow a pair,’ were the words she used. Then she hung up.

It was nice to feel loved.

Magic and I made it to the second-floor landing and I stopped to rest my skinny arms. I pushed the dog’s overgrown backside to the floor and gingerly touched my armpits, which were rubbed raw from the crutches.

As I pushed her down, Magic’s feet slipped and her entire body flattened to the wood. I wondered if I should have left Magic in the apartment. But if the man came back up in the lift, what would he do to her? I thought of the black umbrella shifting to the side and the man’s eyes looking up at me through the crooked tree branches. That thought drove me down the last two flights of stairs.

I stopped in the small foyer at the entrance to the building. The room was dimly lit and had the same dark timber on the walls as my father’s place. The front door was straight ahead. I could exit onto the street and go to the police station a hundred or so metres from here. But I needed to know what happened to the man who fell. What if he was still alive now but by the time I got back from the cops he wasn’t?

I turned right and moved quickly down a narrow corridor towards a door that had a green ‘EXIT’ sign above it. I figured it opened onto the backyard of the building. I pressed my ear to the door. It felt cold on my skin. I heard nothing from outside.

I would just take a peek, then I’d go to the police. I eased the door open, the bottom of it scraping loudly on concrete. I pushed my eye to the gap and peered into the backyard. The bin shed was pressed up against the building, sulking in the gentle rain. It was covered in dead brown vines and smelt bad even from a few metres away. It stood between me and where the man had landed beneath the leafless tree. Above it was an expanse of pink-lit cloud, no stars.

There was no sign of anyone in the yard. Police hadn’t arrived. Was it possible that no one else had heard the strangled noise of the man falling? Or the sickening thump of him hitting the ground? Or had they? Maybe, in a city, when you heard something like that, you closed the blinds and ignored it, tried not to get involved. Maybe you learnt not to care.

Close the door and go to the police. Or go back upstairs.

But the apartment didn’t feel safe now either. The man had looked right at me. He knew what I had seen. Maybe he went up in the lift. He was probably outside Harry’s door at this very moment.

I needed to know if the other man was alive. People could survive big falls. I had seen it in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not book in the school library – a Ukrainian woman who survived a seventeen-storey fall because she was asleep. It helped if your body was very relaxed. But the guy who fell from the sixth floor had sounded tense and nervy, not relaxed at all.

I pressed my ear to the crack of the open door. Moan of garbage truck, squeal of brakes, noisy clashing of bins being collected. That noise seemed to go on all night in the city. There was a siren, but in the distance. No sounds from within the small yard. I took a deep breath, pushed the door open some more and squeezed out into the rain. Magic followed. I let the door rest gently against the lock, making sure it didn’t click shut. I scanned the courtyard. The only movement was from one enormous moth dive-bombing the security lamp. A moth should not be out here in the rain and cold.

There was a broken toy gun on the ground a couple of metres away. I thought about taking it with me for protection but it didn’t look very realistic. I wedged it in the door to make sure it didn’t close.

I stayed near the brick wall of the apartment building and crutched slowly, silently towards the dead-black shape of the bin shed.

FOUR

THE BODY

I dodged around a bike chained to a clothes line and a crushed pot plant that must have fallen from a windowsill or a balcony. Kicked by one of the men? My crutches sloshed in small puddles and cold rain trickled down my neck and back. Magic strained at her collar, excited to be outside in the rain and breeze. I moved quickly to the door of the bin shed and peeked inside, alert for human shapes. The shed was about three metres wide and four metres long. It was empty. The wheelie bins must have been out in front of the building, lined up on the kerb.

I crutch-crept across the cracked pavers on the floor of the shadowy shed. Wind flurried outside, rustling the dead vines above and blowing a shiver right through me. Magic made a strange, high-pitched whine and I stopped for a moment, loosening my grip on her lead.

This is the dumbest thing I have ever done, I thought. And, according to Mum, I had done some pretty dumb stuff recently.

This is so typical of you, Sam. Even when she wasn’t with me, her voice was there. Can you please, just once, try to do the right thing? Make. Good. Choices!

I made it to the doorway on the other side of the shed. I had a clear view of the ground beneath the tree where the man had fallen. The patchy grass was painted with the knobbly shadows of tree branches, but the body was gone. The man had either crawled away or someone had taken him. It seemed to me that his crawling days were over, so that left only one possibility.

I spied a narrow driveway at the side of the building – just wide enough for a vehicle and blocked by a tall double gate. I had seen the caretaker’s dirty ute enter the yard through there earlier in the week.

I prayed that Magic would bark and bite rather than lick and sniff if we came upon the large man under the black umbrella. I eased my way out into the starless night, moving slowly towards the place where the smaller man had landed. I looked behind me and left and right but there was no sign of life.

I stopped and leaned heavily on my crutches. I pushed Magic’s bottom down again and the dog fell, spread-eagled in the mud, like a bearskin rug.

I thought about how my father might investigate a crime scene like this. I was pretty sure that’s what it was. Someone had pushed that man and then taken the body in the time it took me to get downstairs. I had never been at a crime scene before.

God is in the details. That was number one in ‘Harry Garner’s Ten Commandments of Crime Reporting’, an article that had been published about my father in the Herald a couple of years ago. I had the clipping folded up in my wallet and I read it all the time.

God is in the details. Don’t miss a thing, I heard my dad whisper to me. I had been probing him about his work all week. He’d told me that there are a couple of key things he focuses on at a crime scene in order to describe it clearly for his readers: Photograph and document the scene without contaminating it. Take note of any obvious physical evidence, like weapons or footprints; and biological evidence, like blood, hair and other tissues.

I noticed small, dark spatters on the grass – either mud or blood. I took a shot on my phone. It made a loud ch-kshhh sound as it snapped and I flicked it to mute. There was a shallow depression in the dirt where the man had landed, the weight of his life etched into the earth. I felt tears prick my eyelids. I swallowed hard, leaned down as far as my leg would allow and took a couple of shots of the hollow in the ground.

I touched the earth and wondered who the man was: if he’d had kids, if he left any mark on the world other than this one in the backyard of a shabby apartment building in a pretty bad part of the city.

I picked up a small piece of paper from the ground. A receipt, wet through from the rain and impossible to read. Magic yawned excitedly and looked as though she wanted to eat it.

Maybe it was evidence or just something that blew out of a bin. I took a photo and pocketed the receipt carefully, so as not to tear it. As I straightened up, there was a dull thud somewhere nearby.

I probably should have run but instead I froze, not breathing. I waited for a shadow or a voice. Seconds ticked by. No other sounds. I looked up at Harry’s apartment, the window still ajar. I half-expected to see someone looking down at me. I scanned the other windows and bal conies. All of them were closed against the cold and rain. I turned my attention to the ground once more.

I wondered if I had compromised the crime scene. Maybe the hoof-prints of my crutches had destroyed vital evidence.

Something glinted in the lamplight a couple of metres away. I moved closer, careful not to tread on the man’s indent. It was the arm from a pair of glasses. I picked the evidence up by the very tip, trying not to contaminate it with my fingerprints, and slipped it into my pocket.

There was a sound and I looked up to see one of the large gates at the side of the building begin to open. I panicked. ‘Magic, come,’ I whispered, pulling the dog to her feet by her lead. I crutched awkwardly towards the door to the apartment building.

What if it’s help? I wondered. What if it’s Harry? That’s what would happen in Harry Garner: Crime Reporter, my comic book series. I had been making the books for three years and I was up to issue seven. I wasn’t that good at drawing at first but I was getting better. In the books, Harry always saved the day. Or the night.

But I was not in a comic book and I wasn’t taking any chances. I imagined Death shadowing me as I lunged with my crutches, reaching ahead and swinging my legs forward. Magic waddled double-time to keep up. A couple of metres before I reached the door to the building I launched my crutches forward, smelling safety, and they slipped in the mud, sending me sliding onto the ground. I broke my fall with the palms of my hands and my bandaged right knee. Pain surged through me and I lost my grip on Magic’s lead but fear picked me up and sent me hopping to the door. I opened it and the plastic gun fell out onto the mud.

‘Come, girl!’ I pleaded with Magic. ‘Come!’

She ambled over, squeezed through the gap and I eased the door shut behind me, the bottom of it grating against concrete. I crutched down the narrow corridor to the foyer. I should have gone through the double doors and directly to the police station. But I didn’t want to be out on the streets of an unknown city, hobbling on crutches at 2.30 in the morning. What if the man had an accomplice who was waiting out front?

I eyeballed the lift that my father had strictly forbidden me to travel in. It was waiting there, calling me. My arms were tingly and numb, the top of my crutches cutting the blood flow, and I was wet and cold. I didn’t know if I could make it all the way upstairs and I was 94 per cent sure that Magic couldn’t.

I thought of the person coming through the gate in the backyard. I was pretty sure it was the creepy man with the umbrella, so I swung my leg forward and pulled the heavy old-fashioned lift door open. Magic shuffled in and I crutched after her into the tiny space, the smallest lift I had ever been in. I hit the ‘5’ button and prayed that I was doing the right thing.

The lift didn’t move so I tapped the button ten times in quick succession like it was my Xbox controller when the game wouldn’t load. Finally, it reeled upwards. I watched through the wire mesh window as the floors slowly, painfully drifted by. I wondered if I’d have been faster crutching up the stairs, if the man would walk up and be waiting for me at the top.

Why didn’t you go to the police? I thought over and over, the question rattling and squeaking through my brain like the lift through the shaft.

After what felt like an hour we arrived at level five and the lift made a soft, out-of-tune ding. I peered through the narrow window in the door, looking left and right. I couldn’t see anyone. Only the doors to 5A and 5B and, in between, the fire hose reel cupboard. I wondered if he had already called the lift from the foyer. Just in case, I pressed the button for every floor so that it would take forever to get down. I shoved open the door and Magic waddled out. I crutched across to Harry’s apartment, inserted the key and twisted. Magic pushed the door open with her nose, barrelled past me and slurped water noisily from her four-litre ice-cream container on the kitchenette floor.

I clicked the door quietly closed, my chest burning, feet freezing, listening for dear life. Magic collapsed to the floor. Her breathing sawed through the air, making it difficult to listen for the lift or for noises on the staircase.

‘Shhhh,’ I told her, but the chubby brown dog kept wheezing.

I called out ‘Harry?’ and checked the bedroom and bathroom again. Then I stood, watching the door for a couple of minutes, listening. I checked my phone.

Nothing.

Harry will be back soon, I thought.

I’ll just pop out and grab some milk. That’s what he’d said. I shouldn’t have asked him all those personal questions. I’d sent him away. It was my fault.

I heard the distant sound of a timber door grating on concrete five floors down.

FIVE

THE CUPBOARD UNDER THE STAIRS

I clicked the cupboard door closed and sank into the darkness. The space was narrow, deep and reeked of cleaning products. The mouldy smell of wet mop cut through the chemicals. My nose twitched. I squeezed it to stop myself from sneezing and felt the sting across my cheeks and forehead. Magic panted, her heaving breaths filling the cupboard. The building’s heating system moaned all around. It was the most obvious hiding spot in the world, I knew that – right opposite our apartment, beneath the stairs next to the lift.

The pain just above my knee was apocalyptic and my hands and armpits ached. I started to complain to myself about my broken body but I stopped. I had learnt to do that. It was easy to whinge all the time but it didn’t change anything. Kids don’t let you forget that you walk funny. My spine was bent and my left leg was 5.5 centimetres shorter than my right. That’s why Dr Cheung had inserted the staples into my right leg last week, to slow the growth of the thigh bone. He reckoned it would allow my left leg to catch up, correct the dogleg in my spine and make me normal. I was scared of the surgery but scared of what might happen to my body if I didn’t have the surgery. Knowing that I was coming to Harry’s for the week after the operation had helped me push through the fear.

I heard the lift clanking up through the shaft and soon it arrived on our floor. The door screeched open. There were fast footsteps and a thump. I pressed my ear to the thin cupboard door. Another thump, louder this time. And one more, then something clattering to the ground. It sounded like he had forced Harry’s apartment door.

I imagined him moving across the lounge room, past my sofa bed and into Harry’s room, and I felt sick and angry.

Just soften, Mum would say. You don’t always have to be on the attack. What’s got into you? You’re acting like a teenager.

Well, guess what? I am one. Almost.

I would turn thirteen tomorrow.

Something fell to the floor in the apartment. A book or ornament. Harry didn’t have many. Cupboards were opened and closed. Maybe someone else would hear it, too. Maybe one of the neighbours would come. Or Harry. Maybe he would come home.

After a minute or two the muted thuds and bangs eased. I clamped Magic’s snout shut to quiet the panting. She tried to shake her head from my grip but I wouldn’t let go.

The floorboards on the landing squeaked again as the man moved out of the apartment. He stopped. I could imagine his eyes resting on the cupboard door under the stairs. Magic’s breathing would give us away. Saliva dribbled out of her soft, warm mouth onto my hands but I held on.

I had a flash in my mind of the man looking up at me from five storeys below. I balanced on my chopstick of a left leg and silently shifted my grip on the crutch. I held it low and tight so that if the man opened the door I could deliver a hard, fast blow right up under his nose. I had never done anything like that before but my characters did that stuff all the time. It was easier to be violent with a pencil than it was with a crutch. I wondered if a blow like that could be deadly. I hoped not. I didn’t want to hurt anyone but I was pretty sure that the man did not have my best interests at heart.

Shhhhh-shhhhh-shhhh-shhhhh, said Magic’s nose, then I heard the grind and pop of floorboards as the man walked, slow and cautious. I felt the board beneath my foot rise gently. Maybe he was standing on the other end, pushing my end up like a seesaw. Could he feel my weight? The resistance? He coughed a big, meaty cough, and I felt the vibration of it along the board and up through my bare foot. I was all fear. No flesh or bones or breath. Pure fear. He knows I’m here. He knows.

I heard what sounded like two sprays of an asthma puffer. The floorboard lowered. The man moved off, suppressing another cough. I heard a door open nearby. A neighbour? No. Maybe the fire hose reel cupboard opposite the lift. He was checking in there. That meant he would check in my cupboard, too. He would be silly not to. I clutched that crutch handle like my life depended on it, because it did.

There were footsteps. The lift door screeched open, closed, and then it started moving off, down through the building and away.

SIX

THE APARTMENT

Before I opened my eyes I heard the roar of city traffic below. I waited for the sound of my father pouring hot water into his big Herald mug, jiggling three tea bags, stirring in four heaped teaspoons of sugar, plopping in a splash of milk and dropping the spoon noisily into the sink.

The sounds did not come. In their place was the huffing of Magic sleep-breathing, and the diabolical stench of her breath. I opened my eyes on almost complete darkness. My bottom felt as hard and cold as the timber floor beneath me. My leg was twisted. I tried to straighten it and felt bone grind against bone or metal beneath my skin.

Is Harry home? Maybe that’s what woke me.

Details of our last conversation washed over me. ‘Why do you think you and Mum broke up?’ That’s what I’d asked. Like an idiot. He had been at the dining table, laptop open, keeping an eye on the screen as he paged through a notebook, scribbling. I was tucked into the sofa bed, watching him. It must have been about 10 pm when I asked the question. He muttered an answer about ‘two people who love each other very much but sometimes…’ and so on. Mum had given me this one many times, but I wanted the truth. So I asked if he had thought about me much over the years and he ummed and aahed and got up to make tea. ‘Course I have,’ he said. ‘All the time.’

I asked why he had never been in touch and if he got the letter I sent. I was sitting up now. I really wanted to know. He stayed over in the kitchenette, not looking at me, as the jug boiled and roared. ‘Do you think I’ll see you again after this week?’ I asked.

He grabbed his coat off the back of a dining chair and said, ‘I’ll just pop out and grab some milk. I’ll only be a minute. You go off to sleep. It’s late. We’ll talk about all this tomorrow.’

And that was it. He hadn’t come back. If I hadn’t pressed him maybe I wouldn’t be in this predicament.

I pushed up with my good leg and eased my back up the cupboard wall. Magic struggled to her feet, too, yawning eagerly into the darkness. There was a weak crack of daylight beneath the door. I checked my phone: 6.06 am.

I eased the door open. Magic tap-danced around my feet. My stomach lurched and acid scratched at my throat as I peered out. The front door to my father’s apartment was open about a third of the way but I couldn’t see inside.

Someone ran downstairs from the floor above, making old timber groan right above my head. I panicked and closed the cupboard door again. Was it someone from the apartment directly above my father’s? 6A? The footsteps moved quickly across the landing and down the next flight of stairs. Not heavy footsteps. Light. A jogger. A lady or a kid. The girl I had seen through the peephole in Harry’s front door on Monday, maybe? Probably her. She was the only person I had heard or seen using the stairs. Was she from the apartment where the man fell? Had she been asleep? Was the big, asthmatic man her father? I couldn’t rule it out. Never assume anything. Number six in Harry’s Ten Commandments.

I carefully pushed the cupboard door open again. Magic scurried past me, sniffing the fire hose reel cupboard, then sniffing around the door of apartment 5B, the one next to ours.

The stairwell smelt like breakfast and sounded like morning TV.

I moved slowly towards Harry’s apartment, my mud-spattered feet so cold they no longer seemed to exist. My bandage was wet and filthy from my fall in the yard. I didn’t remember the doctor suggesting mud and lots of exercise to heal my leg.

‘Harry?’ I whispered.

I listened for movement.

‘Harry?’

I willed my father to appear – black shoes, smart grey pants, crisp white shirt, trench coat, collar up, neat black hair. Just like in Harry Garner: Crime Reporter. I imagined him just as I drew him and for some reason, in that moment, I couldn’t think what the real Harry looked like. I needed to hear him speak, to say to me, ‘How’d you sleep, fella?’ like he had every morning this week, to make him real again.

Magic sniffed at our door, nudging it wider. I grabbed her collar and saw the mess inside the apartment. The furniture was all in place and Harry didn’t have many possessions, but what had been on shelves or in drawers was now strewn on the floor – paper, books, food, a few ornaments, cushions.

Magic strained at her collar, trying desperately to run off into the apartment. In the end, I couldn’t hold her. The dog darted inside, feet sliding on the matting, her tail stiff. She sniffed everything that had fallen.

I flicked on the light, checked behind the door, then went to the kitchenette. I slid open a drawer and wrapped my icy fingers around a large knife. I gripped it tight and crutched across to the bathroom, knife pointed forward like a bayonet.

I listened through the ruckus of Magic’s doggy detective-work. I stopped a couple of metres back from the bathroom, took a breath and listened to the bath tap drip onto that rusty stain. I tried to think of my dad looking in the mirror each morning, plucking grey hairs from the side of his head as though it would somehow stop more from growing. He would stand back and look at himself, pleased, like he didn’t even see the other 25,000 grey hairs.

I edged forward and peered around the doorframe, a white-knuckle grip on the knife. But Harry was not at the basin. I approached the mouldy shower curtain that was pulled around the bath. I couldn’t remember whether the curtain had been pulled across when I’d checked the bathroom during the night. A lot had happened since then. My hand shook with the knife in it. I wasn’t sure if I had the guts to use it. My teeth chattered quietly.

I reached my left crutch out towards the curtain and my mind flicked through every scary comic I had ever read. I waited for an explosion of human body through curtain or a single deadly shot. Thwack. Pow. Kaboom.

SEVEN

THE VISITOR

There was nothing. Just that rusty-red stain. Drip… drip… drip. I reached into the bath and squeaked the tap hard clockwise, but the drip would not stop.

I moved out of the bathroom and into the bedroom, twisting and turning to look behind the door and flick open the wardrobe. I dropped awkwardly to the floor to see under the bed.

Nobody.

I had checked the entire apartment. I laid the knife on the floor. In a horror comic like Weird Terror or Tales from the Crypt, this was the part where the killer rolled out from nowhere, grabbed the knife and plunged it deep into the victim’s chest.

I picked up the knife and rested it in my lap. As I did, I heard someone bounding up the stairs. I crawled to the bedroom door, dragging my crutches and leg behind me. I peeked out, saw the front door still open and stood awkwardly, leaning against the bedroom doorframe. I crutched across the lounge room, the footsteps still winding their way upwards. I pressed myself against the wall as a shadow appeared on the front door. I took a chance and peered out to see the girl from upstairs – dyed red hair, black sweat pants, black hoodie, white earbuds and an earring up high on her left ear. She looked a year or two older than me.

She saw me and looked startled. I withdrew into the apartment and waited till she had gone by. I peered out again and she looked back at me as she climbed the next flight of stairs. Then she was gone, up the final flight to the sixth floor.

I pushed the door closed. It banged on the jamb and swung open again. The deadlock was lying on the dirty lino of the kitchen floor with splinters of wood still attached to it. I closed it again and rested my forehead against the murky-grey-painted timber.

Why didn’t I ask her if she heard anything? I wondered.

My phone vibrated in my pocket. I took it out and stared at the screen.

Mum. My heart rose and sank simultaneously. What would I say? She would expect a message back right away. Otherwise she would call and I couldn’t have that. I was tired and confused and scared, and I would tell her everything. I didn’t want to. I didn’t want her to have to save me.

My mother had honed the fine art of over-parenting me from a distance. When I was little she only worked three days a week at the hospital, but when I was in second grade she said that we needed more money. So she started doing five, sometimes six days, mostly in Emergency, which meant that they asked her to stay back if there was a car accident or some other big event. She couldn’t afford to say no. I used to like going to my cousins’ house while she was at work but, lately, it felt like she was hardly ever at home or awake when I was. Sometimes early shifts, sometimes late. But, even though she wasn’t physically at home, she always seemed to be there looking over my shoulder – texting and calling, checking in, knowing what I was doing before I knew. I clicked on the message.

Morning Sammy. Did you

sleep well?

Sammy. I had told her about using that name. I wondered how I could answer honestly without telling her that I had witnessed a possible murder, that the perpetrator was after me and that my father was missing. Sometimes mothers needed to be protected from small pieces of disturbing information.

Morning Lisa.

Bit restless

Not exactly a lie, I figured.

Don’t call me Lisa.

Don’t call me Sammy

You’ll be home tomorrow.

I’ve missed you. I’m sorry

I let you go.

I know. You told me that.

It’s okay

I didn’t think I had any

choice.

It’s okay

I’m a terrible mother.

No you’re not

Well he’s a terrible father

and I’m a terrible mother for

letting you stay

with him.

I know Mum. You’ve told me that

before too

Many times, I wanted to add, but I didn’t.

ok

‘ok’ was Mum-speak for ‘I’m sad that you seem to be enjoying yourself so much and sorry I said anything’. The short, lower-case answer came with an invisible sad-face emoji. I felt bad. My mum was an emotional wreck. Probably because of me. She was a good person. She did everything for me. Why did I have to upset her all the time? And the truth was that I really hadn’t been enjoying myself so much. Even before Harry went out for milk. I hadn’t told her about him working every day, being late every night, about how impatient he’d been with all my questions, and about him being old and distant and smelling slightly weird.

Take your magnesium.

She thought magnesium would solve everything – my jumpy legs, stomach pains, anxiety, inexplicable rage and ‘very poor decision-making’. So far, only the jumpy legs had been cured. I went over to the bed, my leg howling in pain now that the tide of adrenaline had gone out. I flopped down, reached into my backpack, grabbed a small brown glass bottle of magnesium, shook a couple of tablets out into my hand and chewed them.

Just took some

Good boy.

‘Good boy’ was another thing I had banned her from saying, especially in front of my friends. Mum wanted me to be four years old forever. She had, so far, chosen to ignore the hairs poking from my chin. There were only three of them but I was letting them grow out. There was no way she hadn’t seen them. If I pressed my chin to my chest in the bath they were really spiky.

Are you looking forward to

your party? Lachie’s mum

messaged me to say he

could come.

I had forgotten about my party. It wasn’t really a party. Just friends coming over to play video games and watch movies.

Yep. Great

Bye teenager.

Bye little old lady

Watch it.

I squeezed my phone into my pocket and spent a few minutes wrestling a heavy armchair up against the front door, hopping on my good leg. I shoved the coffee table behind the armchair for extra protection and stood back, assessing my work.

Magic looked up at me, smiling. I opened the fridge and took out a pizza box. There were two pieces of two-day-old Meatlovers. We had eaten pizza five of the six nights I’d been staying with Harry. He would nibble one piece and I’d devour about seven. He couldn’t believe how much I ate. Every night he’d watch me, shake his head and say, ‘You must have holes in the bottoms of your feet.’ Which I took as a challenge to eat more.

I’d told Harry that pizza was my favourite food on my first night but now I wasn’t so sure. I could feel a soccer ball of mozzarella cheese pocked with ham and pineapple sitting in my gut. On Tuesday night, the only non-pizza night, I had tried to surprise him by making pasta with red sauce, a recipe we’d made in Food Tech at school – but it was cold by the time he got home at 7.30.

I grabbed the two pieces of pizza, left the box in the fridge, dropped one piece on the floor for Magic and took a bite out of the other. It was like eating the sole of a sneaker. Magic inhaled hers then looked up at me with a twinkly ‘give-me-that-pizza-or-I-may-bite-you’ eye. I dropped my slice on the floor and gave her a pat as she vacuumed it up.

I crutched over to the sofa bed, dog-bone tired and sore all over. The dressing on my leg was caked with mud and a bit of blood. I took a clean dressing from my backpack and peeled off the old bandage. It was pretty messy under there with fresh blood and a clear, yellowy liquid seeping from between the stitches. I prayed that the fall in the yard and all the knocks to my knee hadn’t displaced my staples. Mum had spent thousands on the operation, even after Medicare. She had told me this at least twelve times in the lead-up. I cleaned the knee with a sharp-smelling medical wipe, wrapped my leg the way Tina had taught me in the hospital and stretched the little elastic catch across to secure the bandage.

I put on some fresh shorts and a t-shirt and called Magic, who was still desperately licking and sniffing the floor for pizza crumbs. She toddled towards me. I reached down, put my arm beneath her ample backside, hauled her up onto the bed with a groan and, within seconds, I was tumbling down into sleep.

EIGHT

HOW I WONDER WHO YOU ARE

I had thought about my father every day of my life for as long as I could remember. Sometimes more than once. I wondered where he was. I wondered who he was. I wondered who I was. I knew that I was a Scottish-French-Aboriginal Australian. Whatever that meant. My mum’s side was Scottish and she’d told me that Dad’s was French and Aboriginal a couple of generations back. And I was me. But I felt like my dad held some vital piece of the puzzle and if I could just get to know him, then I could unlock who I was and I’d have all the answers. Or some of them.

I asked Mum about him a lot. He wasn’t a popular topic of conversation, but I couldn’t help myself. If your dad lived two hours away from you and you had never met him, wouldn’t you be curious? At least once a day – when I was in maths or walking home from school – I thought, ‘I wonder what he’s doing now?’

Sometimes, when people have body parts removed, they feel as though the part is still attached. They call it a ‘phantom limb’. Well, my dad had never been part of my family but I still sensed him like a missing body part. It was as though I was born without a left leg and yet, every day, I was surprised that I didn’t have a left leg. The space in my life where he should have been seemed to tingle and itch and sometimes burn.

Reading his articles helped. From fourth grade on, I made sure I got to the bus stop in the mornings with fifteen minutes to spare so that I could cross the road to the newsagency and scour the pages for one of his stories. I would flick and flick through the paper, praying to see the words in bold print at the top of a story: By Harry Garner. Sometimes there was nothing but, when there was, it made my stomach drop. It was cool to see my own name in a newspaper: Garner. I liked that. But it was mostly about seeing my father’s name. It made him real. I loved hearing his voice in the stories, the way he strung words together, the way he looked at the world. I built him up so much in my head that he became magical and mythical.

I wanted to tell Mrs Li, the newsagent, but she was usually glaring at me in a ‘this is not a library’ kind of way. Sometimes the bus would arrive when I was in the middle of a really juicy story and I’d have to finish reading it online at school, but I preferred to read it in print. After I had started one of his articles I would hardly talk to anyone on the bus. I’d stare out the window imagining what was going to happen at the end. He had this way of unravelling a crime like it was fiction – not in a boring way like a normal newspaper story about the Prime Minister or the economy, but in a way that made you need to know what happened next.

Harry covered murders, robbery sprees, prison escapes. His life seemed so much more interesting than mine. Nothing ever happened to me. I lived in the most boring town since the invention of towns, while I imagined my father was living an amazing life in the city: reporting crime, earning lots of money and living in a big house with no one to tell him what to do.

That’s why I started making my comic. I wanted to get down what I thought it must be like for him, and imagine my own future life as a second-generation crime reporter.

I once tried calling him at home on a number I found in my mum’s phone but it rang out ten times. Another time, my mum let me try to call him at work at the Herald. I was so nervous, but I actually got to speak to him. The only time in my life until this week. The call was only short. He was just about to go away and he said he couldn’t meet up with me, but that he’d call when he got back. He didn’t know exactly when he would be back. Probably an overseas assignment, I figured. He couldn’t tell me so it must have been a really big story. When I got off the phone I didn’t want to look at my mother’s face, didn’t want to see her pity or outrage or anything. I just wanted to be alone and to stop the hot sacks of tears beneath my eyes from spilling over.

My dad was busy. I understood. He had an important job. I’d meet him one day. I knew I would. Maybe I’d even live with him sometime. I didn’t mention that plan to Mum. But I knew. One day. And it would be perfect.

NINE

TRUST ME

I heard a loud bang. And another.

I didn’t know where it was coming from at first. I wasn’t deep enough asleep to be dreaming. I was still diving into the well of it. Bang. Hearing the noise, I tried to slow my fall and, for a moment, I didn’t know which way was up or down. I heard Magic bark for the first time since I’d arrived and I fought my way to the surface. Not such a bad guard dog after all, I thought as my eyes flicked open. I sat up.

Bang. The armchair and coffee table shunted back. I stood, grabbed my crutches and started towards the bathroom to hide as quickly and quietly as I could.

I heard a man grunt as the door was rammed again. It opened a crack and the tip of a hat appeared. The armchair and coffee table inched back across the floor. A head and body squeezed through the narrow gap. I stopped, the tips of my fingers resting on the bathroom doorhandle.

He stood, panting. Short, lopsided – one shoulder lower than the other. Dirty grey hat. Shirt untucked. Scuffed black shoes.

‘What happened?’ he asked.

Tears spat from my eyes. I tried to stop them but couldn’t. I felt so thankful and angry he was home. I crutched across to the door and hugged him, something we had never done before. His body was stiff and I didn’t know if he wanted me to hug him or not but I didn’t care. At the same time, I kind of wanted to scream at him for leaving me alone. But he must have had a good reason or he wouldn’t have left me. Surely. If it was Mum I’d have yelled at her without a second thought, but it’s easier to be angry at people you know.

He smelt like alcohol, which was strange because he said he hadn’t had anything to drink in nearly a year.

Magic ran over to us, skidding on the kitchen lino. Harry broke the hug and scruffed her neck, checking out the wreckage in the apartment. ‘What happened?’ he repeated.

‘Where were you?’ I asked, wiping tears away. ‘You said you were going for milk.’

He shuffled inside, shoved the door closed and looked around at the chair and table rammed up against the door, the deadlock lying on the floor. I noticed him sway a little and he rested a hand on the bench to steady himself. He was Captain Haddock in Tintin after too many whiskies.

‘Somebody broke in,’ I told him.

‘What?’ He squinted as though I was speaking another language. He looked crumpled and grey and old. He was older than any other kid’s father in my class. Old enough to be my grandfather, really. Mum had warned me but I had still been surprised when I first saw him in the flesh. The little square photo they used for his feature articles in the Herald must have been taken in about 1992.

‘And a man died,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘Out there,’ I said. ‘He was pushed.’

Harry’s face fell straight and serious. ‘What do you mean?’

‘A man was pushed from up there.’ I pointed towards the sixth-floor balcony.

‘When? Tell me what happened,’ he said.

I relayed everything I had seen and heard. I acted out parts of it. I pointed to where the man had landed. I showed him the receipt and the arm of the glasses. He drank a steaming, three-bag, four-sugar tea, black, as there was still no milk, and listened carefully. I showed him my photos – the blurry one taken when I bumped the window, and the close-ups of the indent in the earth and other evidence at the crime scene. I watched his reactions carefully. I wanted him to say I’d done well, but he didn’t. He did not take notes. My comic-book Harry wasn’t a note-taker either.

He went to the small, round dining table. ‘Where’s my laptop?’

I grabbed my backpack and gave it to him. ‘I was trying to look after it.’

Harry opened the laptop, turned the screen away from me and sat down. ‘And the other man?’

‘I didn’t really see him that well. He had a sort of high-pitched voice and he sounded small. I think he was small, but I couldn’t really tell from up here.’

He tapped some keys and stared at the screen.

‘What are you looking up?’ I asked.

He ignored me, tapped some more, stared at the screen again for another minute or two.

I was desperate to know.

‘Oh, god,’ he said, still watching.

‘What?’ I asked, trying to see.

He closed the lid and looked at me, wide-eyed, as though he was staring right through me.

‘I’m sorry I went out.’

‘It’s okay,’ I said, even though I didn’t really think it was okay.

‘Do you think anyone else saw what happened?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think so. It was just me. Is it something to do with your story? Should we go to the police?’

He gazed out the window, his eyes bleary and hair a mess, unshaven, unwell.

‘Are you okay?’ I asked.

‘Not really.’

‘Did you have something to drink?’ I asked. ‘I thought you didn’t–’

‘I slipped up,’ he said. ‘I’ve had a lot to think about this week. And before you ask your next question, can you just give me a moment?’ He hobbled over to the armchair that had been wedged against the door and flopped into it. Magic rested her head in his lap. Harry took off his shoes and socks. His feet were road-mapped with thick blue veins. The skin on top of his feet was thin, the soles hard and yellow and crusty. I would never draw the Harry Garner in my comics like this. He looked way too real.

My Harry, superhero crime reporter, was an expert in jujitsu and boxing. He was a polyglot, which meant that he knew lots of languages – nineteen, in fact, including Swahili, just in case I decided to set a story in Kenya or Mozambique. He was rich and he travelled the world without even taking a suitcase. He could ride a motorbike, scuba-dive, fly a helicopter and captain a submarine in a pinch. He was a computer hacker and arms expert. He skied in Switzerland and climbed live volcanoes in Hawaii for exercise. Women loved him and men wanted to be him.

But sitting here, drunk and old, in this tiny apartment with peeling blue paint on the walls, was the real HG. My dad. Maybe the next issue of Harry Garner: Crime Reporter would be called ‘The Real Harry Garner’ and he’d have sore knees and a fat brown dog. At least I didn’t have to worry about people cancelling their subscriptions. That was the one advantage of me being my only reader.

‘Do you think we need to go to the police?’ I asked again.

‘No,’ he snapped. I think he realised how sharp his voice sounded and he softened. ‘Not right now. Listen, how would you feel about going home a day early?’

‘Home? Why?’

‘I have to go to work today.’

The thought of him leaving me again sent adrenaline racing through my veins.

‘It’s not safe for you here,’ he said. ‘I appreciate your telling me all these details but I think you’d be better off at home. I’ll give your mum a call. Maybe I can put you on a train this morning rather than tomorrow.’

He hoisted himself out of the armchair and limped towards the bedroom. He had a short leg and crooked spine like mine, but worse. He was what Dr Cheung had said I would become if I didn’t have the operation. And he seemed even more crooked after being out all night.

‘Please,’ I said to him. ‘I don’t want to go home yet. Can I stay?’ Even as I said the words, part of me regretted them. What if the man came back?

Harry took a fresh shirt from the wardrobe, turned and looked at me from under his thick, grey brows.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Please.’ I crutched towards him. ‘I can come to work with you. I won’t bother you.’

‘I don’t do the kind of work where I can–’

‘I’ll stay out of your way.’

‘You can’t come with me, all right?’ he said firmly, shrugging on the shirt.

‘Well, can I stay here?’

He motioned towards the mess at the front door, the lock lying on the floor. He pulled a fresh pair of pants from the wardrobe and pushed the bedroom door closed.

‘He won’t come back,’ I said, raising my voice so Harry could hear me. ‘We can put another lock on the door. I want Mum to think this went well. She won’t want me to come back here if you send me home early. Please, it’s only one night. I won’t be any trouble. I’ll go home tomorrow like we planned.’

I waited. He said nothing for a minute or two and I knew that he was going to say no. Eventually the bedroom door swung open and he stared at me.

‘Why would you want to be here with me?’ he asked.

I wondered if it was a trick question. ‘Because you’re my dad,’ I said.

He stared at me for a moment. ‘Please don’t hold me up as any kind of hero. Your mum deserves all the credit for the way you’ve turned out. You make sure you’re good to her.’

I nodded. ‘I will.’

‘You promise me?’

I nodded again.

‘If you see or hear anything even slightly suspicious you’ll call me or send me a message right away?’

‘Yeah.’

He rubbed his face with his hands.

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘You can stay till tomorrow morning.’

TEN

SOLVE IT

Harry drove the final screw into the deadlock and mopped sweat from his forehead with a dirty tea towel. He had been to the mini Mitre 10 on the corner the minute it opened, bought two locks and a screwdriver and spent forty minutes fixing the locks to the door. They looked a little bit crooked to me, maybe because he had been drinking, but judging by the number of times he swore, it seemed like Harry didn’t do a lot of DIY. But it was done. I would stay till tomorrow morning.

‘I’ll be back by six,’ he said. ‘Hopefully before. Don’t open the door for anyone. Do you understand?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘And are you sure you can be back by six because–’

‘I’ll be back by six. You have my word. And are you sure you can send me a message if you need to? You’ve got enough credit or whatever?’

‘Enough for messages.’

‘Well, I’m only a few blocks away. If you hear or see anything…’

I nodded. I wanted to suggest again that we go to the police. He must have read my mind.

‘Give me today,’ he said. ‘I’ll be back as soon as I finish work and I’ll tell you more then. I just need some time to check some things. You’ve played hard, done good, telling me this information and now you have to trust me, Sam. Can you do that? Can you trust me?’

I wanted to. I really did.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I can trust you.’

He unlocked the two new deadlocks, opened the door and said, ‘See you tonight.’

I wanted more than anything to go with him. I felt tired and like I might start bawling again so I just said, ‘Okay.’

Harry slipped out the door. ‘Lock it up,’ he said in a low voice.

I pushed the door closed and twisted the brass knobs. He tested the door and then said, ‘I love you.’

‘Huh?’ I asked.

I heard his quiet footsteps fade down the staircase.

Then it was just me and Magic again.

I love you? I thought. He had never said that before. Sure, he had said it through a door and then scurried away, but he had still said it. Hadn’t he?

I kneeled on Harry’s unmade bed and peered through the dirty window and down Victoria Street. I waited for him to appear, hobbling along in his coat and hat.

The young homeless lady in the purple puffer jacket was on the corner of the street diagonally opposite, breathing clouds of steam through cold air, shaking her paper coffee cup, asking for donations. I’d seen her on a couple of other days when I’d watched Harry leave. The lady was outside Pan, the bakery that Harry had gone to more than once during the week. The last few orange leaves fluttered down from the almost-bare tunnel of trees over the street.

Harry crossed the road towards Pan. I desperately wanted to go down in the lift and follow him. I did not want to be here alone. Watching him from above, I saw how bad his limp was, how bad mine might have become if Mum hadn’t forced me to have the operation. He heaved open the heavy door of the bakery and, a moment later, a woman – chocolate-brown hair, knee-length black coat – exited, coffee and brown paper bag in hand. Harry followed her out. His girlfriend? I wondered. That made me angry. I don’t know why. Why shouldn’t he have a girlfriend? Still, the uncomfortable feeling stayed with me.

‘Watch the bad feeling but don’t engage with it.’ That’s what Margo would say. She was a therapist Mum had been sending me to. I called her my coach. Her voice was annoyingly soothing but I kind of liked her anyway. She read comics, especially The Phantom, and she talked with me about them. Not in a fake adult way where she pretended to be interested just to make me have a conversation with her, but in a real way where she actually knew stuff.

‘Don’t push the anger away or act it out,’ she would say. ‘Just let it sit there. What’s behind it? Moods are like clouds passing the sun. Let them pass.’

In that moment, watching this lady coming out of the bakery with my dad, I felt really annoyed. He said he had to go to work and that he couldn’t stay with me or take me with him but he seemed to have time for her. As soon as I noticed that I felt annoyed, though, and I named it, the feeling kind of drifted away, like a cloud. It was one of the first times that I’d been able to do what Margo suggested and it actually worked.

I pulled out my phone, switched to camera, zoomed in and took a bunch of pictures. The woman looked much younger than Harry. Was she another journalist or maybe a cop? She could have been either. A criminal? Maybe. Probably not. She didn’t look like a criminal. But what was a criminal supposed to look like? A scar on her face? Shifty eyes and rubbing her hands together, like a bad guy in an old movie?

Commandment number six: Never assume anything. And don’t convict people. That’s the job of the courts. Just report the facts. Be as objective as you can. Innocent until proven guilty.

Harry and the woman walked off up Victoria Street, turning right at a little laneway with a backpackers’ hostel on the corner and disappearing from view. I wanted so badly to follow them. Where are they going? What is he going to do till 6 pm? Had he planned to meet her? Is he telling her about the crime I witnessed? Or is it totally unrelated?

I looked back through the pixelly, zoomed-in photos on my phone, then turned and looked around Harry’s dimly lit bedroom.

Solve it, said a voice in my head.

I didn’t feel sleepy at all now. I felt jumpy and alive.

Solve it.

7.57 am.

Harry was due to put me on the 8.01 train back to the Mountains tomorrow morning. I only had today to find out more. When Harry came home at six I would show him the fresh evidence I had found. He would be pleased. I could be useful to him, like a researcher or an assistant. He would love me for it. Maybe we could find the perpetrator of the crime and the man who fell. I had always wanted to be a crime reporter. Maybe this was my chance.

ELEVEN

HARRY GARNER’S TOP TEN COMMANDMENTS OF CRIME REPORTING

1. God is in the details. Gather as many details as you can about the crime. Observe colours, sounds, textures, smells, even tastes.

2. Make contacts. You have to know crime fighters as well as criminals. You need sources of good information on underworld dealings.

3. Watch what you say about people. Build trust.

4. Sometimes criminals will try to make you see things their way. These are dangerous and often charismatic characters. You need to be clear with people which side of the law you sit on.

5. Don’t keep everything on a phone. It can be hacked for content and the digital trail you leave can be used as evidence in court by both police and criminals. Phone towers know where you are.

6. Never assume anything. And don’t convict people. That’s the job of the courts. Just report the facts. Be as objective as you can. Innocent until proven guilty.

7. Always be authentic. Don’t make things up or sensationalise the story.

8. Is the crime part of something bigger? Does it reflect changes happening in society? What does it say about us as humans?

9. Curiosity killed the cat. Be careful of becoming too obsessed. Sometimes a story can eat you up and take you to dangerous places, physically and mentally.

10. Show determination, patience, mindfulness. Evaluate all evidence.

TWELVE

SNOOP

I sat on the windowsill and stared down through the bare tree branches. Fragments of what I had seen and heard last night flickered through my mind. That flash of black. His voice. The slunching sound of impact. The bang of my phone on the window. The round, white moon of the man’s face emerging from beneath the black umbrella.

The yard didn’t look as scary during the day. Trains snaked by, in and out of the city. Rain still fell. I could see where he had landed but not the shape of him, not from up here. But I could imagine it.

I felt a gut impulse to go back down there. I knew it was stupid but I wanted more than anything to find more evidence to show Harry.

I had promised to stay inside. He made me promise.

I turned away from the window, pushed the temptation aside.

I looked around the apartment. Harry had cleaned up a bit but there were still bits of broken bowl swept into the corner and open books spread across the floor like dead birds.

How can I help Harry? I wondered. Maybe the man had left DNA evidence in the apartment. I couldn’t test it but I could gather it. I had read stories about a single hair being used to convict a criminal even forty years after the crime had been committed.

And if this crime had something to do with the story Harry was working on, maybe there were notes or photos hidden somewhere in the apartment – if the man hadn’t already found them in the night. I could use them to help my own investigations.

I was pretty much addicted to snooping. At home, I knew where Mum kept chocolate (on top of the pantry in a plastic tub with the medical supplies), Christmas presents (window seat, under the spare pillows) and my Xbox controllers (bottom cupboard, behind the rice cooker).

I grabbed the back of a dining chair and awkwardly dragged it across the floor into the bedroom, in front of the old timber wardrobe. The chair wobbled as I swung my good leg onto it. I took a deep breath and pushed up, grabbing the top of the wardrobe for balance. Magic licked my toes.

‘Stop!’ I whispered sharply but she didn’t listen.

I felt around the top of the wardrobe. I was close to the ceiling, which meant I was close to the floor of 6A. Is anyone up there right now? I wondered. Magic continued to lick between my toes.

I couldn’t see what was on top of the wardrobe but I ran my fingertips through inch-thick dust, searching for anything Harry may have hidden.

My thumb scraped something flat and metallic. My heart skipped as I pried the object off the timber. A key. A very dusty key. Not from Harry, though. This key had been here a long, long time and my father had only lived here a month or so. I sneezed, wiped the dust on my shorts and lowered myself off the chair. I felt the sting of my stitches pulling and the deep throb of the staples grinding against my bones. I sat on the floor and pressed myself flat to the timber so that I could look under the bed.

Nothing. Just more dust bunnies. Not as thick as on the wardrobe. They were more like dust rabbits up there.

I sat up and looked at the brassy-brown key. It had a serial number carved into it. It was a regular key, not an old one. I twisted around, placed my hands on the edge of the bed frame and pushed myself up. My arms were so sore. I kept my leg straight, grabbed my crutches and hobbled out to the kitchen bench, where the busted lock was sitting with a hunk of splintered timber still attached. I picked it up and tried the key but it wouldn’t fit.

I went to the windows, trying to protect my red-raw armpits from the tops of the crutches. The windows didn’t have locks. I couldn’t think of anything else in the apartment that did. The key was no good to me for now.

I wondered if any of my evidence or photos had anything to do with the crime that had been committed. Maybe none of it was useful.

I continued to search the apartment – through every drawer, inside every book, under every cushion and pillow and mattress. The only thing that seemed to be gone was the electricity bill that had fluttered to the floor when I grabbed Harry’s laptop off the dining table. This played on my mind. Maybe Harry had picked it up, taken it with him. Possibly. But what if the man had picked it up? He would have Harry Garner’s name linked to this address. I thought about messaging Harry but decided not to bother him. I didn’t want him getting annoyed with me. I would tell him after work.

I searched the medicine cabinet, the fridge and oven. The walls were lined with timber from floor to chest height, then there was a small ledge and plasterboard up to the ceiling. I tapped the timber part of the wall, hunting for some kind of secret cavity. The fire hose reel cupboard was set into the other side of this wall but it mustn’t have taken up the whole space because, over by Harry’s front door, the wall sounded hollow. I tried to get my fingertips in between the boards but they were all nailed in tightly – there was no way to check what was behind them.

I decided to make a note on my phone of all my father’s personal items:

• 1 toothbrush, green and white, cheap, bristles chewed and splayed

• 1 tube Macleans toothpaste, almost empty

• 1/2 packet of Quick-Eze indigestion tablets. Use-by date: 2/2/13

• Fridge: rotten pear; empty pizza box; jar of chopped chilli

• Cupboard: packet of Uncle Ben’s Instant Rice; tin of Heinz baked beans; tin of Edgell red kidney beans; Saxa picnic salt; an onion with a green stalk growing out of it

• Wardrobe: 2 pairs of grey trousers; 2 white, long-sleeved button-up shirts (one with a pink stain on front); 6 pairs of underpants, all white-ish, two with holes near waistband at back; 1 pair of shoes

• 1 laptop and charger

• 1 hunting knife

I had to admit that the last one worried me. I found it in a very thin drawer at the bottom of the wardrobe between two larger drawers. Why does my father need a knife? He owned barely anything but he had this long, jagged knife with a black handle. Reporters in comics had guns. But my dad had a hunting knife. What was he hunting? Criminals?

What if he was involved in this crime? Is that how he knew something? Is that why he ignored me when I suggested going to the police?

I pushed the thought aside. It was stupid.

But was it? I hardly knew Harry, only a made-up, comic-book version of him. I met him six days ago and, before that, he was a fantasy to me. I had pictured calling him ‘Dad’ but instead he made me call him ‘Harry’. I imagined we’d have all these really big talks but, a lot of the time, he wasn’t even home. He had promised Mum that he would take the week off but he just kept working. ‘I haven’t had a day off in forty years,’ he told me. I believed him but I also thought that meeting his almost-thirteen-year-old son might be a good enough reason to have one. Sometimes it felt like he was avoiding me on purpose, like he didn’t know what to say or do when he was around me. That’s why he went out last night.

‘Crime reporter’ would be the perfect job for a criminal. He could know what the cops were thinking and he could feed that information into the underworld. His fourth commandment of crime reporting was:

Sometimes criminals will try to make you see things their way. These are dangerous and often charismatic characters. You need to be clear with people which side of the law you sit on.

But what if Harry hadn’t been clear? He had been reporting crime for forty years. That’s a long time to interact with these ‘charismatic characters’ and stay clean. Maybe he started out on the right side but at some stage he slipped. But that sounded suspiciously like a crazy plotline for one of my comics. It was ridiculous. My father was a crime reporter, not a criminal.

A sound popped out from the general background hum of traffic: the rev of an engine close by. I crutched over to the window and looked into the yard. There was an old guy down there with long silver hair but a bald patch on top. The caretaker of the building. He was climbing out of a rusty white ute parked right next to the bin shed, near where the man had fallen. The caretaker was wearing grey overalls, the kind that cover your arms and legs. I’d watched him come and go a couple of times during the week. When you’re stuck in an apartment by yourself every day you get to know the rhythm of the place. His shoulders were rounded, neck bent forward. He reminded me of a tortoise, especially on the day, earlier in the week, when he had worn the backpack for weed-spraying.

He clicked the door of the ute shut then walked back out of the gate and hauled all the bins in, two at a time, parking them in the bin shed. When he was done he poked his head out of the shed, looked around the yard, then up at the building. I pulled back from the window. I left it a few seconds, then I looked down again.

The man went into the shed and was out of view for maybe half a minute. I watched and waited. He emerged carrying a couple of black plastic bags. I wondered if they had been in there when I went through the shed last night or if they had been put there since. I slid my phone out of my pocket and took three quick shots of him as he threw the bags into the tray of his ute. He looked around and up again, then walked towards the building. I had to press my face right against the glass to keep him in view. I tried taking another shot but it was all reflection and windowsill. I wanted to open the window but was worried the noise would alert him.

He opened a door or a gate at the base of the building. I had seen him put a lawnmower in there earlier in the week. On Tuesday, I thought. The gate made a clink-screek sound as it opened.

I had heard that sound several times during the week. The clink of a metal latch, then the screek of rusty hinges as the gate opened. It was the sound I had heard last night after I saw the man standing over the body, after he looked up at me and I pulled back from the window.

Clink-screek.

Had he hidden something in that cupboard? And what if the thing was still there?

I leaned out the window to get a better look but the caretaker just closed the gate with a screek-clink and threw a shovel and a piece of folded black plastic into the back of his ute.

I needed to go down there. This guy had to be involved in some way.