Nate Heller is a cop trying to stay straight in one of the most corrupt places imaginable: Prohibition-era Chicago. When he won’t sell out, he’s forced to quit the force and become a private investigator.

His first client is Al Capone. His best friend is Eliot Ness.

His most important order of business is staying alive.

Max Allan Collins

True Detective

To Barb with love

He felt like somebody had taken the lid off his life and let him look at the works.

1

The Blind Pig

December 19 — December 22, 1932

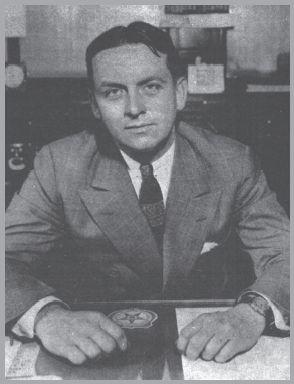

Frank Nitti

1

I was off-duty at the time, sitting in a speak on South Clark Street drinking rum out of a coffee cup.

When two guys in topcoats and snap-brim hats came in and walked over without crawling out of ’em, I started to reach for the automatic under my jacket. But as they neared the table, I recognized them: Lang and Miller. The mayor’s bagmen.

I didn’t know them exactly, but everybody knew them: the two Harrys — Harry Lang and Harry Miller, the detectives handpicked by Mayor Cermak to handle the dirty linen. Lang I’d spoken to before; he was a guy about ten years my senior, thirty-seven or eight maybe, and a couple of inches under my six feet, a couple pounds over my 180. He had five-o’clock shadow and coal black hair and cold black eyes and the sort of shaggy eyebrows you don’t trust; even the impression of hair was a lie: under the hat his forehead kept going. Miller was forty and fat and five eight, with a blank face and blanker eyes — the kind you can take for stupidity if you aren’t careful. He was cleaning off the lenses of his wire-frames with a hanky, the glasses having got fogged up in the cold. His ears stuck out; when he put his glasses on, they stuck out more. The Coke-bottle lenses magnified the blank eyes, and it struck me he looked like an owl — an owl that could kick the crap out of an eagle, that is.

Before he was a cop, Miller was a bootlegger — one of the Miller Gang, who were West Side Boys. That made it Old Home Week: we were all West Side Boys. Maxwell Street, where my father’s stall had been, was where I knew Lang from.

But I didn’t know Lang well enough to merit the old-drinking-pals camaraderie he suggested in his words if not his tone: “Hiya, Red. Heard you hung out here.”

Red wasn’t my name. Heller was. Nathan Heller. Nate. Never Red, despite my mother’s reddish-brown hair I was carrying around.

“The joint’s halfway between Dearborn and LaSalle Street stations,” I shrugged. “It’s handy for me.”

It was around three in the afternoon, and we had the place pretty much to ourselves: just me, the mayor’s front-office dicks, the guy at the door, the guy behind the bar. But it was a cramped, boxlike joint with lots of dark wood and a mirror behind the bar and framed photos everywhere: celebrities and near-celebrities, signatures on their faces, were staring at me.

So were Lang and Miller.

“Buy you a cup of coffee?” I said, rising a little. I was a plainclothes officer, working the pickpocket detail, bucking for detective status. These guys were the best-paid detectives in town, sergeants yet, and they maybe didn’t deserve respect, exactly, but I knew enough to give them some.

They made no move to sit down. Lang just stood there, hands in his topcoat pockets, snow brushing his shoulders like dandruff, and rocked on his heels, like a hobbyhorse; but whether it was from nerves, or from boredom, I couldn’t say: I could just sense there was something I wasn’t being let in on. Miller stood planted there like one of the lions in front of the Art Institute, only meaner-looking. Also, the lions were bronze and he was tarnished copper.

Then Miller spoke.

“We need a third,” he said. He had a voice like somebody trying to sound tough in a talkie: monotone and slightly off-pitch. It should’ve been funny. It wasn’t.

“A third what?” I said.

“A third man,” Lang chimed in. “A third player.”

“What’s the game?”

“We’ll tell you in the car.”

They both turned toward the door. I was supposed to follow them, apparently. I grabbed my topcoat and hat.

The speak was on the corner of Clark and Polk. Out on the street the wind was whipping at package-clutching pedestrians heading for Dearborn Station, which was around the corner and a block down, where I should be getting back to, to protect these shoppers from losing whatever dough they had left after Marshall Field’s got through with them. Skirts and overcoats flapped, and everybody walked with heads lowered, watching the pavement, ignoring the occasional panhandler; dry, wind-scattered snow was like confetti being tossed out of the windows during a particularly uninspiring parade. Across the way the R.E.A. Station was busy, trucks pulling in and out, others being loaded up. Four women, pretty, in their late twenties, early thirties, bundled with packages, went giggling into the speak we’d just exited. It was a week to Christmas, and business was picking up for everybody. Except for Saint Peter’s Church, maybe, which was cattycorner from where we stood; business there looked slow.

There was no parking in and near the Loop (which was loosely defined as the area within the El tracks), but Lang and Miller had left their black Buick by the curb anyway, half a block down, across the street; it was the model people called the Pregnant Guppy, because the sides bulged out over the running boards. The running board next to the curb had a foot on it: a uniformed cop was writing a ticket. Miller walked up and reached over and tore it off the cop’s pad and wadded it up and tossed it to the snow-flecked breeze. He didn’t have to show the cop his detective’s shield. Every copper in town knew the two Harrys.

But I liked the way the uniformed man handled it, a Paddy of about fifty who’d been pounding the beat longer than these two had been picking up the mayor’s graft, that was for sure. And clean, as Chicago cops went, or he wouldn’t still be pounding it. He put his book and pencil away slowly and gave Miller a look that was part condescension, part contempt, said, “My mistake, lad,” and cleared his throat and shot phlegm toward Lang’s feet. And turned on his heel and left, swinging his nightstick.

Lang, who’d had to hop back, and Miller, his face hanging like a loose rubber mask, stood watching him walk away, wondering what they should do about such unbridled arrogance, when I tapped Lang on the shoulder and said, “I’m freezing my nuts off, gentlemen. What exactly is the party?”

Miller smiled. It was wide but it didn’t turn up at the corners and the teeth were big and yellow, like enormous kernels of corn. It was the worst goddamn smile I ever saw.

“Frank Nitti’s tossing it,” he said.

“Only he don’t know it,” Lang added, and opened the door on the Buick. “Get in back.”

I climbed in. The Pregnant Guppy wasn’t a popular model, but it was a nice car. Brown mohair seats, varnished wood trim around the windows. Comfortable, too, considering the situation.

Miller got behind the wheel. The Buick turned over right away, despite the cold, though it shuddered a bit as we pulled out into light traffic. Lang turned and leaned over the seat and smiled. “You got a gun with you?”

I nodded.

He passed a small .38, a snubnose, back to me.

“Now you got two,” he said.

We were heading north on Dearborn. We drove through Printer’s Row, its imposing ornate facades rising to either side of me, aloof to my situation. One of them, tall, gray, half-a-block long, was the Transportation Building, where my friend Eliot Ness was working even now; he seemed a more likely candidate to be calling on Al Capone’s heir than yours truly.

“How’d you finally nail Nitti?” I asked after a while.

Lang turned and looked at me, surprised, like he’d forgotten I was there.

“What do you mean?”

“What’s the charge? Who’d he kill?”

Lang and Miller exchanged glances, and Lang made a sound that was vaguely a laugh, though you could mistake it for a cough.

Miller, in his monotone, said, “That’s a good one.”

For a second, just a second, despite the gun I’d been handed, I had the feeling I was being taken for a ride. That somehow I’d stepped on somebody’s toes and whoever it was was big enough and hurt bad enough to take it on up to the mayor, who Christ knows owed plenty of people favors, and now His Honor’s prize flunkies were driving me God knows where — Lake Michigan maybe, where a lot of people went swimming, only some of them had been holding their breath underwater for years now.

But they didn’t turn right, toward the lake; they turned left at the Federal Building — which meant the Chicago River was still a possibility and the Union League Club ignored us as we passed. We turned again, right this time, at the Board of Trade. We were in the concrete canyons of the financial district now — and by concrete canyons, I mean just that: in the thick of Chicago’s loop, you can see towering buildings at left and right and front and back. Chicago invented the skyscraper and never lets you forget it.

The dustlike snow wasn’t coming down hard enough to collect, so the city remained gray, though touched with Christmas red and green: most office windows bore poinsettias, and every utility pole had sprigs of holly or balsam; and now and then an ex-broker in what used to be a nice suit sold bright red apples at a nickel per. Just a few blocks over, on State Street, it would’ve looked a little more like Christmas, albeit a drunken one: the big stores with their fancy window displays were high on drinking paraphernalia this year, cocktail shakers, hip flasks, hollow canes, home-brew apparatus. All of it legal, but a violation of the law’s spirit, as if hookahs were being publicly sold and displayed, just because public opinion suddenly sanctioned smoking dope.

We passed the Bismarck Hotel, where the mayor often lunched; it hadn’t been so long ago that the famous old hotel had changed its name to the Randolph, after its location on the southeast corner of Randolph and Wells, to assuage anti-German sentiments during the Great War, though nobody had ever called it the Randolph, and a couple years back the name went back to Bismarck, officially. We were on the Palace Theater side, where Ben Bernie and his Lads had top billing (“Free Gifts for the Kids!”) and the picture was Sports Parade with William Gargan; across the street was City Hall, its Corinthian columns and classical airs making an ironic facade for the goings-on within. Then we crossed under the El, a train rumbling overhead, and I decided they were kidding about Frank Nitti, because the Detective Bureau was on our left and we’d obviously been heading there all along — only we went past.

In the 200 block of North LaSalle, City Hall just a block back, the Detective Bureau less than that, Miller pulled over to the curb again, no parking be damned, and he and Lang got out slowly and I followed them. They drifted casually toward the Wacker-LaSalle Building, a whitestone skyscraper on the corner, the Chicago River across the street from it. A barge was making impatient noises at the nearby example of the massive drawbridges Big Bill Thompson gave the city, but its iron shoulders didn’t even shrug.

Inside the Wacker-LaSalle, a gray-speckled marble floor stretched out across a large, mostly empty lobby, turning our footsteps into radio sound effects. On the ceiling high above, cupids flew halfheartedly. There was a newsstand over at the left; a row of phone booths at the right; a bank of elevators straight ahead.

Halfway to the elevators, more or less, in the midst of the big lobby, a couple of guys in derbies and brown baggy suits were sitting in cane-back chairs with a card table set up between them, playing gin. They were a Laurel and Hardy pair, only Italian, and Laurel had the mustache; both had cigars, as well as bulges under one arm. We were a stone’s throw from the financial district, but these guys weren’t brokers.

Hardy glanced up at the two Harrys, recognizing them, nodding; Laurel looked at his cards. I looked ahead at the building registry, in the midst of the elevators with their polished brass cage doors: white letters on black, coming into focus as we neared. Import/export, other assorted small businesses, a few lawyers.

We paused at the elevators while Miller cleaned his thick wire-frames again. When they were back on his head, he nodded and Lang hit the elevator button.

“I’ll take Campagna,” Miller said. It sounded like he was ordering drinks.

“What?” I said.

They didn’t say anything; they just looked at the elevators, waiting.

“‘Little New York’ Campagna?” I said. “The torpedo?”

An elevator came; a guy in another brown suit with matching underarm bulge was running it.

Lang put a finger on his lips to shush me. We got on the elevator and the guy told us to stand back. We did, and not just because he was armed: in those days when you were told to stand back on an elevator, you listened — there were no safety doors inside, and if you stood too near the front and took a shove, you could lose an arm.

He brought us up to the fifth floor: nobody was posted up here; no comedians with guns playing cards. Nobody at all with a bulge under his arm. Just gray walls and offices with pebbled glass in the doors with numbers and, sometimes, names. We were standing on a field of tiny black-and-white tiles — looking down the hallway at the receding mosaic of them made me dizzy momentarily. The air had an antiseptic smell, like a dentist’s office, or a toilet.

Lang looked at Miller and pointed back to himself. “Nitti,” he said.

“Hey,” I said. “What the hell’s going on?”

They looked at me like I was an intruder; like they didn’t remember asking me along.

“Get a gun out, Red,” Lang said to me impatiently.

“It’s Heller, if you don’t mind,” I said, but did what he said, as he did likewise. As did Miller.

“We got a warrant?” I said.

“Shut up,” Miller said, without looking at me.

“What the hell am I supposed to do?” I said.

“I just told you,” Miller said, and this time he did look at me. “Shut up.”

The blank eyes behind the Coke-bottle glasses were round black balls; funny how eyes so inexpressive could say so much.

Lang interceded. “Back us up, Heller. There may be some shooting.”

They walked. Their footsteps — and mine, following — echoed down the hall like hollow words.

They stopped at a door that had no name on its pebbled glass — just a number, 554.

It wasn’t locked.

Miller went in first, a.45 revolver in his fist; Lang followed, with a .38 with a four-inch barrel. I brought up the rear, thoroughly confused, but leaving the snubnose Lang gave me in my topcoat pocket: I carried a nine-millimeter automatic, a Browning — unusual for a cop, since automatics can jam on you, but I liked automatics. As much as I could like any gun, that is.

It was an outer office; a desk faced us as we entered, but there was no secretary or receptionist behind it. There were, however, two guys in two of half a dozen chairs lining the left wall — two more brown suits, topcoats in their laps, sitting there like some more furniture in the room.

Both were in their late twenties, dark hair, pale blank faces, average builds. One of them, with an oft-broken nose, was reading a pulp magazine, Black Mask; the other, with pockmarks you could hide dimes in, was sitting smoking, a deck of Phillip Morris and a much-used ashtray on the seat of the chair next to him.

Neither went for a gun or otherwise made any move. They just sat there surprised — not at seeing cops, but at seeing cops with guns in their hands.

In the corner to the left of the door we’d just come in was a coatrack with four topcoats and three hats; the right wall had another half dozen chairs, empty. Just behind and to the left of the desk was a water cooler and, in the midst of the pebbled-glass-and-wood wall, a closed door.

Then it opened.

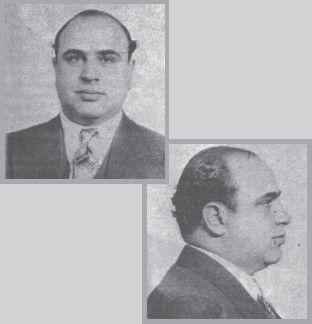

Standing in the doorway, leaning against the jamb, was a man who was unmistakably Frank Nitti. I’d never met him, though he’d been pointed out to me a few times; but once having seen him, you couldn’t miss him: handsome, in a battered way, fighter’s nose, thin inverted-V mustache, faint scar on his lower lip; impeccably groomed, former barber that he was, slick black hair parted neatly at the left; impeccably dressed, in a gray pinstripe suit with vest, and wide black tie with a gray-and-white pattern. He was smaller than Frank Nitti was supposed to be, but he was an imposing figure just the same.

He closed the door behind him.

There was a look on his face, upon seeing the two Harrys, that reminded me of the look on that uniformed cop’s face. He seemed irritated and bored with them, and the fact that guns were in their hands didn’t seem to concern him in the least.

A raid was an annoyance; it meant getting booked, making bail, then business as usual. But a few token raids now and then were necessary for public relations. Only for Nitti to be involved was an indignity. He’d only been out of Leavenworth a few months, since serving a tax rap; and now he was acting as his cousin Capone’s proxy, the Big Fellow having left for the Atlanta big house in May.

“Where’s Campagna?” Lang said. He was standing with Miller in front of him, partially blocked by him. Like Miller was a rock he was hiding behind.

“Is he in town?” Nitti said. Flatly.

“We heard you were siccing him on Tony,” Miller said.

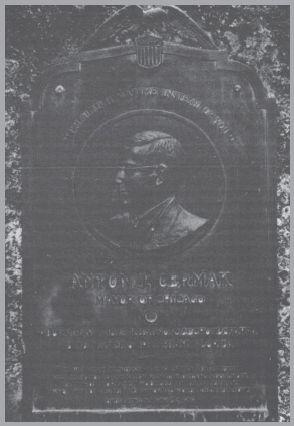

Tony was the mayor: Anton J. Cermak, alias “Ten Percent Tony.”

Nitti shrugged. “I heard your bohunk boss is sleeping with Newberry,” he said.

Ted Newberry was a Capone competitor on the North Side, running what was left of the old “Bugs” Moran operation.

Silence hung in the room like the smell of wet paint.

Then Lang said to me, “Frisk the help.”

The two hoods stood; I patted them down with one hand. They were unarmed. If this was a handbook and wire-room setup, as I suspected, their being unarmed made sense; they were serving as runners, not guns. Lang and Miller taking their time about getting into the next room also made sense: most raids were conducted only for show, and this was giving the boys inside time to destroy the evidence.

“Let’s see if Campagna’s in there,” Lang said finally, nodding toward the closed door.

“Who?” Nitti said, with a faint smile.

Then he opened the door and went in, followed by his runners, then by Miller, Lang, and me.

The inner room was larger, but nothing elaborate: just a room with a table running from left to right, taking up a lot of the space. At right, against the wall, was a cage, and a guy in shirt sleeves wearing a green accountant’s shade was sitting in there with a bunch of money on the counter; he hadn’t bothered putting it away. Perhaps it wouldn’t all fit in the drawer. At left a young guy stood at a wire machine with a ticker tape in his hand, only this wasn’t the Board of Trade by a long shot. Two more sat at the table: another one in shirt sleeves, his back to us, suitcoat slung over the chair behind him, four phones on the table in front of him; and across from him, a hook-nosed hood wearing a pearl hat with a black band at a Capone tilt. There were no pads or paper of any kind on the table, though there were a few scattered pens and pencils. This was a wireroom, all right. The smoking wastebasket next to the table agreed with me.

The guy in shirt sleeves at the table was the only one I recognized: Joe Palumbo. He was a heavyset man with bulging eyes and a vein-shot nose; at about forty-five, the oldest man in the room with the exception of Nitti, who was pushing fifty gracefully. The hood in the Capone hat was about thirty-five, small, swarthy, smoking — and probably Little New York Campagna. The accountant in the cage was in his thirties, too; and the kid at the ticker tape, with curly dark hair and a mustache, couldn’t have been twenty-five. Lang ordered the accountant out of the cage; he was a little man with round shoulders and he took a seat at the table, across from Palumbo, next to the man I assumed (rightly) to be Campagna, who looked at the two Harrys and me with cold dark eyes that might have been glass. Miller told the runners to take seats at the table; they did. Then he had the others stand and take a frisk, Campagna first. Clean.

“What’s this about?” Nitti asked. He was standing near the head of the table.

Lang and Miller exchanged glances; it seemed to mean something.

My hand was sweating around the automatic’s grip. The men at the table weren’t doing anything suspicious; their hands were on the table, near the phones. Everyone had been properly searched. Everyone except Nitti, that is, though the coat and vest hung on him in such a way that a shoulder holster seemed out of the question.

He was just standing there, staring at Lang and Miller, and I could feel it starting to work on them. Campagna’s gaze was no picnic, either. The room seemed warm, suddenly; a radiator was hissing — or was that Nitti?

Finally Lang said, “Heller?”

“Yes?” I said. My voice broke, like a kid’s.

“Frisk Nitti. Do it out in the other room.”

I stepped forward and, gun in hand but not threateningly, asked Nitti to come with me.

He shrugged again and came along; he seemed to be having trouble deciding just how irritated to be.

In the outer office he held his coat open as if showing off the lining — it was jade-green silk — and I patted him down. No gun.

The cuffs were in my topcoat. Nitti turned his back to me and held his wrists behind him while I fished for the cuffs. He glanced back and said, “Do you know what this is about, kid?”

I said, “Not really,” getting the cuffs out, and noticed he was chewing something.

“Hey,” I said. “What the hell are you doing? Spit that out!”

He kept chewing and, Frank Nitti or not, I slapped him on the back and he spit it out: a piece of paper; a wad of paper, now. He must’ve had a bet written down and palmed it when we came in; hadn’t had a chance to burn it like the boys inside did theirs.

“Nice try, Frank,” I said, grasping his wrists, cuffs ready, feeling tough, and Lang came in from the bigger room, shut the door, came up beside me and shot Nitti in the back. The sound of it shook the pebbled glass around us; the bullet went through Nitti and snicked into some woodwork.

I pulled away, saying, “Jesus!”

Nitti turned as he fell, and Lang pumped two more slugs into him: one in his chest, one in the neck. The .38 blasts sounded like a cannon going off in the small room; a derby dropped off the coatrack. Worst of all was the sound the bullets made going in: a soft sound, like shooting into mud.

I grabbed Lang by the wrist before he could shoot again.

“What the hell are you—”

He jerked away from me. “Easy, Red. You got that snubnose?”

I could hear the men yelling in the adjacent room; Miller was keeping them back, presumably.

“Yes,” I said.

Nitti was on the floor; so was a lot of his blood.

“Give it here,” Lang said.

I handed it to him.

“Now go in and help Harry,” he said.

I went back in the wire room. Miller had his gun on the men, all of whom were standing now, though still grouped around the table.

“Nitti’s been shot,” I said. I don’t know who I was saying it to, exactly.

Campagna spat something in Sicilian.

Palumbo, eyes bulging even more than usual, furious, his face red, said, “Is he dead?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think he’s going to be alive long, though.” I looked at Miller; his face was impassive. “Call an ambulance.”

He just looked at me.

I looked at Palumbo. “Call an ambulance.”

He sat back down and reached for one of the many phones before him.

Then there was another shot.

I rushed back out there and Lang was holding his wrist; his right hand was bleeding — a fairly deep graze alongside the knuckle of his forefinger.

On the floor, by the open fingers of Nitti’s right hand, the snubnose .38 was smoking.

“Do you really think that’s going to fool anybody?” I asked.

Lang said, “I’m shot. Call an ambulance.”

“One’s on the way,” I said.

Miller came in, gun still in hand. He bent over Nitti.

“He’s not dead,” Miller said.

Lang shrugged. “He will be.” He turned toward me, wrapping a handkerchief around his wound. “Get in there and watch the grease balls.”

I went back in the larger office. One of the men, the young, nervous one with the mustache, was opening the window, climbing out onto the ledge.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” I asked.

The other men were seated at the table; the young guy who was half out the window froze.

Then somebody at the table tossed him a gun.

Where it came from, who tossed it, I didn’t know. Maybe Campagna.

But the guy had a gun now, and he shot at me, and I got the automatic out and shot back.

And then he wasn’t in the window anymore.

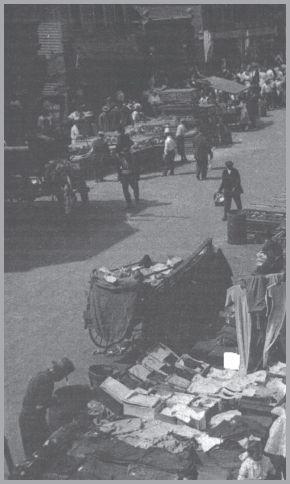

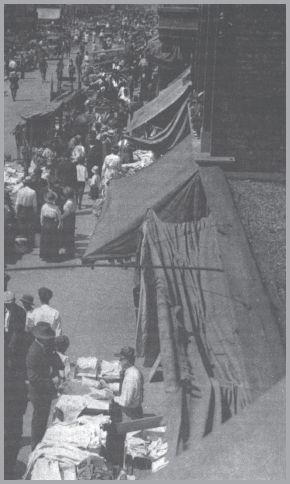

Maxwell Street

Maxwell Street

2

My father never wanted me to be a cop. Particularly not a Chicago cop, the definition of which (my father frequently said) was a guy with change for a five. He’d been a union man, my father, and had been jailed and beaten by police; and he’d always had disdain for Chicago politics, from the butcher down the block who was assistant precinct captain to “Big Bill” Thompson, the mayor who wanted to be known as the “Builder” when “Boozer” was more like it.

Pa would’ve liked nothing more than for me to quit the force. It had been a major stumbling block between us, those last few years of his life. It may have led to his death. I don’t know for sure. He didn’t leave a note that night he shot himself. With my gun.

The Hellers came from Halle, in eastern Germany, orginally, and so did their name: Jews in Germany in the early 1800s were forced to abandon their traditional lack of surname and take on the name of either their occupation or home area. If my name hadn’t been Heller it probably would’ve been Taylor, because a tailor is what my great-grandfather, Jacob Heller, was, in Halle, in the late 1840s.

Which were hard times. The economy was doing handstands due to developing railroads and industry; technology was making jobs obsolete for everybody from the guy who weaved the cloth to the oxcart driver who shipped it. Unemployment flourished, while crops failed and food prices doubled. A lot of people headed for America. My great-grandfather hung on. His business was suffering, yes, but he had contacts with the richer Jews in Halle — moneylenders, bankers, businessmen — and when the region was rocked by political unrest in 1848, great-grandfather watched from the sidelines. He couldn’t afford getting involved: his business depended on an upper-class patronage, after all.

Then the letter arrived. From Vienna, where great-grandfather’s younger brother Albert had lived; had lived: he’d been killed in the March 13, 1848, revolt against Metternich. His brother left an inheritance, which had been placed in the hands of Rabbi Kohn, the rabbi of Vienna’s Reform synagogue. Great-grandfather didn’t trust the mails during such troubled times, and he went to Vienna to pick up the money. He stayed for a few days with Rabbi Kohn, and enjoyed the company of this kind, intelligent man and his gracious family. He was still there when the rabbi and his family were poisoned by Orthodox fanatics.

My great-grandfather was apparently hit hard by all this: political unrest had taken his brother from him; and in Vienna, he’d seen Jew kill Jew. He’d always been a very pragmatic businessman, preferring to be apolitical; and where religion was concerned, he practiced Reform Judaism rather than strict Orthodoxy. But now he renounced his faith altogether, and became apostate. Judaism hasn’t been seen in my family since.

Leaving Halle couldn’t have been easy, but staying would’ve been hard. The secret police that grew up in the wake of the revolution of 1848 were making things tough. So were the Orthodox Jews who attacked my great-grandfather verbally for his apostasy, and who spread the word to his wealthy clients that their tailor’s late brother had been a radical. The latter didn’t help business, certainly, nor did the general economic climate, and my great-grandfather decided, all in all, that America had to be a safer place to raise his family of four (the youngest, Hiram, having been born in 1850, just three years before the family immigrated to New York City).

As a youth, Hiram, my grandfather, worked in the family tailor shop, which was proving a moderately successful business, though Hiram never went into it. He went instead into the Union army at age seventeen. Like a lot of young Jews at that time, he wanted to prove his patriotism: Jewish war profiteers had been giving their fellows a bad name, and my grandfather helped make up for that by getting shot in both legs at Gettysburg.

He returned to New York, where his father had died in his absence, after a long hospitalization. His mother had died ten years before, and now his two brothers and his sister were squabbling over the business/inheritance, the upshot being that sister Anna left the city with a good chunk of the family savings, not to be heard of again for some years. His brothers, Jacob and Benjamin, stayed in New York but never spoke to each other again; they rarely saw Hiram, either, a nearly crippled, isolated man who was lucky to get his job in a sweatshop in the garment district.

In 1871 my grandfather married Naomi Levitz, a fellow sweatshop worker. My father, Mahlon, was born in 1875, my uncle Louis in 1877. In 1884 my grandfather collapsed while working and from then on was totally bedridden, left at home to look after the two boys as best he could, while grandmother continued working. In 1886 the crowded tenement building the family lived in caught fire. Many died in the blaze. My grandmother got my father and uncle out safely, then went back in after grandfather. Neither came out.

My father’s aunt — who had left town with her estimated share of the inheritance — had got back in touch with the rest of the family, letting them know she was “successful.” It was to her the two boys were sent. To Chicago. From the train to the streetcar, the wide-eyed boys were shuttled not to the Jewish section of the near West Side but to the section of the city known as the Levee. The First Ward — home of “Bathhouse” John and “Hinky Dink,” the corrupt ward bosses; site of the most famous whorehouse in the country, the Everleigh Club, run by sisters Ada and Minna, and scores of lesser houses of ill repute. Their “successful” Aunt Anna was a madam in one of the latter.

Not that Aunt Anna was at the bottom rung; not when there were tenements housing row upon row of crib upon crib of streetwalkers taking a load off. Vile establishments, one of which was owned by the police superintendent at one time; several others by Carter Harrison, Sr., five-time mayor of Chicago. And then there were the panel houses, providing rooms furnished only with a bed and a chair, the former occupied by a girl and her client, the latter by the client’s pants; and from a sliding panel in a wall or door, a third party would enter at an opportune moment and make a withdrawal, often at the very moment a deposit was being made.

At the other end of the spectrum were the Everleigh sisters and, before them, Carrie Watson, into whose parlor one could go at least five ways, as there were five parlors in her three-story brownstone mansion. There were also twenty bedrooms, a billiard room, and, in the basement, a bowling alley. Damask upholstery, silk gowns, linen sheets; wine served in silver buckets, sipped from gold goblets.

Then there was Anna Heller’s house. Wine was served there, too; the dozen girls residing there had it for breakfast. This was around 1:00 p.m., and the third liquid meal of their (so far) short day: at noon a colored girl woke these “withered roses of society” for cocktails in bed; they dressed themselves with the assistance of absinthe, and headed down for breakfast. Soon the girls, in pairs, would sit at windows and attract the attention of male passersby. This would be done by rapping on the window and providing a glimpse of what a girl was wearing, if you could call it that: costumes ranging from Mother Hubbards made of mosquito netting to jockey uniforms to gowns without sleeves to gowns without bosoms (or rather, with bosoms out) to nothing. Business was brisk. And by four or five in the morning, the girls would find a novel use for a bed: sleep. Or drunken stupor.

It helped a girl to stay drunk at Anna Heller’s. Anna was known to boast that no act was too disgusting or perverse for her girls — Circus Night was held three or four times a month — and heaven help the girl who made a liar out of Anna. It was said — though this one aspect of his aunt’s business my father never witnessed — that Anna had in her employ six colored gentlemen who resided at a separate dwelling of hers; and that she would take business trips to other cities and return with girls from age thirteen to seventeen, having promised them jobs as actresses. The act Anna had in mind was a predictable one, though her variation wasn’t. A girl would be locked in a room without clothing and raped by the colored gentlemen. In this way a girl became accustomed to “the life” and soon was having wine for breakfast. So it was said, at any rate.

My father didn’t like his aunt; he didn’t like her house or the way she slapped the drunken “chippies” (as she constantly called them) or the way she hoarded the money her girls made her. And she didn’t like the way my father looked at her, a look of silent unveiled contempt (which my father was good at), and so my father got slapped a lot, too.

Anna and my uncle Louis got along fine. The parlor wasn’t a fancy one, but it was upper-grade enough to occasionally attract a clientele that included ward politicans and successful businessmen, bankers and the like, and Louis must have liked the life these men led, or seemed to lead, and got a taste for capitalism. Of course Aunt Anna was a hell of a capitalist herself, so maybe that was where he picked it up. He probably learned to kiss ass watching Anna deal with the politicos and the posher types who occasionally showed up, and he put the skill to good effect by using it back on Anna, playing upon her pockmarked vanity. While Anna made my father stop school after the third grade, making him the bordello’s janitor, Louis was attending a boarding school out east.

My father didn’t like Louis much either, by this point. Louis didn’t seem to notice, or care. When he was home from school out east, that is. If you called that house a home. Anna and my father did have one thing in common, though: a hatred of cops. Pa hated the sight of the patrolmen arriving for their weekly two dollars and fifty cents each, plus booze and food and girls anytime they were in the mood, which was every time. And Anna hated paying the two-fifty, and providing the booze, food, and girls. The beat cops weren’t the only free-loaders: inspectors and captains from the Harrison Street police station held out a helping-themselves hand, as did the ward politicians, for whom my father also built a dislike. These were the same politicians, of course, who were among those my uncle Louis looked up to.

After eastern prep school, Louis returned to Chicago, and Aunt Anna sent him promptly off to Northwestern. And it was about then that she started taking her favorite nephew to the annual First Ward Ball, where Louis would not only see those admired politicians, but rub shoulders with them, and more important ones than just the First Ward ward heelers: Hinky Dink and Bathhouse John themselves, and most every other alderman in town, and bankers and lawyers and railroad executives and prominent businessmen, and police captains and inspectors and maybe even the commissioner; and pimps, madams, streetwalkers, pickpockets, burglars, and dope fiends. Everyone in costume, the men running to knights, gladiators, and circus strongmen, the ladies (most of whom were of the evening) to Indian maidens, Little Egypts, and geisha girls (costumes the newspapers understatedly described as “abbreviated”). The ball filled the Chicago Coliseum every year, a few days before Christmas, and added twenty-five to fifty thousand dollars to the Hinky Dink-Bathhouse John campaign fund.

“Bathhouse” John Coughlin, former rubber in a bathhouse, Democratic alderman from the First Ward, was the showman: he recited (his own) lousy poetry, wore outlandish clothes (lavender cravat and a red sash), and blew a fortune or two on the horses. “Hinky Dink” (Michael) Kenna was the brains, a little man who chewed on his cigars and accumulated a fortune or two while running the Working-men’s Exchange, a landmark Levee saloon; among his contributions to Chicago was establishing the standard rate for a vote: fifty cents. Their First Ward Balls were described by the Illinois Crime Survey as the “annual underworld orgy.” Hinky Dink didn’t care. “Chicago,” he said, “ain’t no sissy town.”

But at the time Uncle Louis was being impressed by the balls of the First Ward, my father was long gone. In 1893, during the Columbian Exhibition — Chicago’s first world’s fair — business at Anna Heller’s had boomed, and extra girls were taken on, and Anna’s iron hand had taken its toll: on the girls and on my father. The syphilis was probably starting to eat Anna’s brain and possibly explained her erratic behavior. When my father exploded at her, his silent contempt finally erupting after his aunt slapped a young woman sense-less, she came at him with a kitchen knife. The scar on his shoulder was five inches long. Pa stayed around long enough for the doctor Anna had on call to come sew up the wound, then hopped a freight south.

He got thrown off the train near 115th Street. The Pullman plant nearby was where he ended up working; a year later he found himself in the midst of a strike, and was one of the militant strikers who got laid off when the strike finally ended.

And so began Pa’s union work: with the Hebrew Worker’s Congress on the near West Side; with the Wobblies on the near North Side; as a union organizer; a worker at various plants, and involved with union actions and strikes...

Uncle Louis took a different path. By now he was a trust officer with the major Chicago bank, Central Trust Company of Illinois, the famous “Dawes Bank,” founded by General Charles Gates Dawes, who went on to be Calvin Coolidge’s vice-president. Aunt Anna died in an insane asylum the year Louis graduated from Northwestern, so he was able to start out with a degree — and an inheritance, which is to say the money off the sale of the brothel and its hookers — and leave his sordid past behind him.

So the occasional meetings thereafter between my father and uncle were strained, to say the least — a polished young financier on his way up, and a radical worker into union organizing — and usually ended with my father shouting slogans and my uncle remaining quiet, expressing his contempt by not condescending to reply, which is funny because that was my father’s favorite tactic. My father, despite his union activities, was not a man prone to losing his temper; his rage he swallowed, like an unchewable piece of meat that couldn’t be spit out because times were too hard. But at my uncle, he would shout; at my uncle, he would vent his rage. So by century’s turn, the two men weren’t speaking; it made for no awkward moments: they didn’t exactly travel in the same circles.

Also, by century’s turn, my father was in love. Having been denied the education Louis got, he’d taken to reading, even before his union interests led him into books on history and economy. Perhaps that was where my father’s capacity for smugness and contempt came from: he had the insecurity-based arrogance of all self-educated men. At any rate, it was at a cultural study program at Newberry Library that he met another (if less arrogant) self-educated soul: Jeanette Nolan, a beautiful redheaded young woman who was a bit on the frail, sickly side. In fact, it was repeated bouts of illness keeping her out of school that led her into reading and self-study (I never found out exactly what her health problems were, though I’ve come to think it may have been her heart). But this only made her all the more appealing to Pa. After all, his two favorite authors were Dumas and Dickens (although he once admitted to me his disappointment when he discovered that the same Dumas wasn’t responsible for both Camille and The Three Musketeers; he had gone through many a year wondering at the versatility of the author Alexandre Dumas, till he found out that pere and fils were different people).

Not long after she and my father started to court, Pa landed in court, then in jail; his work with unions was repeatedly bringing him into conflict with cops, and his arrest came during a textile plant strike, landing him a month in Bridewell Prison.

Which was a hellhole, of course. A sandstone hellhole with no heat, no toilet facilities other than a five-gallon bucket in the corner of a rusty, paint-peeling cell with two wall-suspended bunks with straw mattresses and wafer-thin blankets, and a stench you could almost see. No water in the cells, though each morning at six, prisoners were given a few moments at a trough with cold running water before one of the two cell-mates got his turn at joining the parade of slop cans, which were carried from the cells and dumped outside in huge cesspools and then scrubbed clean with chemicals. And once a week, a gang shower. The shower came in handy after a week in a clay hole, which is where Pa was assigned: a stone quarry; a deep pit where big pieces of limestone got turned into little ones.

Pa was used to hardship; Aunt Anna had seen to that. And he was pretty healthy: he had the same framework as me, roughly six feet with one-eighty or one-seventy attached to it. But one month in Bridewell took its toll even on a healthy man, and he came out twenty pounds lighter — meals ran to a breakfast of bread and dry oatmeal, lunch of bread and thin soup, supper of bread and a concoction that was peas and fragments of corned beef swimming in something unidentifiable, all servings negligible, with the three pieces of bread the only thing that got him and the other prisoners through the day (one odd thing: Pa often said it was the best fresh-baked bread he ever ate), and he had a cough from breathing quarry dust, and was of course very proud of himself for the moral victory of going to jail over a union matter, and loved his martyr’s role.

But Jeanette was not impressed, not with the glory aspects of it, anyway. She was horrified at the condition Pa was in after Bridewell, just as she’d been horrified the times she’d cleaned and bandaged him after strike-related beatings. Before he went to Bridewell, he’d proposed marriage; he’d asked her permission to ask her parents for her hand. She had said she’d think about it. And now she said she’d marry him on one condition...

So Pa left union work.

Pa was no stranger to Maxwell Street; he’d been there, from time to time, passing out political and union literature. He didn’t want to work for a “capitalist” institution, like a bank (he’d leave that to his brother Louis); and he couldn’t work in a factory — he’d been black-listed from most Chicago plants, and the ones where he wasn’t black-listed would only present the temptation of future union work. So he opened a stall on Maxwell Street selling books, used and new, with an emphasis on dime novels, which, with school supplies — pencils, pens and ink, notebooks — attracted kids, who were his best customers. Occasionally, a parent frowned upon the union and anarchist literature that rubbed shoulders with Buffalo Bill and Nick Carter on Pa’s stall; even the similarly politically conscious Jeanette was critical of this, but nothing could sway Pa. And Maxwell Street was a place where you could get away with selling just about anything.

About a mile southwest of the Loop, Maxwell Street was at the center of a Jewish ghetto a mile square, give or take, and on Maxwell Street it was mostly the latter. The Great Fire of 1871, thanks to Mrs. O’Leary’s less-than-contented cow purportedly kicking a lantern over, left Maxwell Street, which was just south of the O’Leary barn, untouched. The Maxwell Street area had a big influx of new residents from the burned-out areas of Chicago, and the now densely populated area attracted merchants — most of them Jewish peddlers with two-wheeled pushcarts. Soon the street was teeming with bearded patriarchs, their caftans brushing the dusty wooden sidewalks, their black derbies faded gray from days in the sun, selling. Selling shoes, fruit, garlic, pots, pans, spices...

By the time Pa opened a stall there, Maxwell Street was a Chicago institution, the marketplace where the rich and the poor would go for a bargain; where awnings hung from storefronts to the very edge of the wooden stalls crowding the curb, the walkway between so dark a tunnellike effect was created, and lamps were strung up so bargain hunters could see what they were getting but not too many lamps, and not overly bright, because it wasn’t to the seller’s advantage to let the buyer get too close a look at the toeless socks, used toothbrushes, factory-second shirts, and other wonders that were the soul of the street. Whether the street had a heart or not, I couldn’t say, but it did have a smell: the smell of onions frying; even the smell of garbage burning in open trash drums couldn’t drown that out. Accompanying the oniony air were the clouds of steam rising from the hot dogs; and when the onions met the hot dogs in a fresh bun, that was as close to heaven as Maxwell Street got.

Pa and his bride moved into a one-room tenement flat at Twelfth and Jefferson, in a typical Maxwell Street-area building: a three-story clapboard with a pitched roof and exterior staircase. There were nine flats in the building and about eighty people; one three-room flat was home for an even dozen. The Hellers, alone in their one room, sharing an outhouse with twenty or thirty of their fellow residents (one outhouse per floor), had room to spare, and maybe that’s what led to me.

I would imagine Pa was living your typical quiet life of desperation: his union work, which meant so much to him, was in the past; taking its place was his stall, in an atmosphere more openly capitalistic than the banks he loathed (and Pa was a well-read, intellectual type, remember; irony didn’t get past him). So all he had in life was his beloved Jeanette, and the promise of a family.

But mother was still frail, and having me (in 1905) damn near killed her. A midwife/nurse from the Maxwell Street Dispensary, pulled her — and me — through; and, later, diplomatically suggested to them, separately and together, that Nathan Samuel Heller be an only child.

Big families were the rule then, however, and a few years later, my mother died during a miscarriage; the midwife didn’t even make it to the house before my mother died in my father’s bloody arms. I think I remember standing nearby and seeing this. Or maybe my father’s quiet, understated but photographically vivid retelling (and he told me this only once) made me think I remembered, made me think it came back to me from over the years. I would’ve been about three, I guess. She died in 1908.

Pa didn’t show his feelings; it wasn’t his way. I don’t remember ever seeing him weep. But losing mother hit him hard. Had there been relatives on either side of the family that Pa was close to, I might’ve ended up being raised by an aunt or something; there were overtures from Uncle Louis, I later learned, and from mother’s sisters and a brother, but Pa resisted them all. I was all he had left, all that remained of her. That doesn’t mean we were close, though, despite the fact that I was helping at the stall by age six; he and I didn’t seem to have much in common, except perhaps an interest in reading, and mine was a casual one, hardly matching his. But I was reading Nick Carter by age ten and used hardbacks of Sherlock Holmes soon after. I wanted to be a detective when I grew up.

Conditions in the neighborhood got worse and worse; shopping in the Maxwell Street Market could be an adventure, but living there was a disaster. It was a slum: there were 130 people crowded in our building now, and the father and son who shared one room were looked upon with envy by their neighbors. There were sweatshops which of course got my union-in-his-blood father’s ire up — and diseases (mother had had influenza when the miscarriage took her, and Pa used to blame the flu for her death, perhaps because in some way it absolved him); and there was the stink of garbage and outhouses and stables. I attended Walsh school, and while I managed not to get involved directly, there were gang wars aplenty, bloody fights in which kids would slash each other with knives and fire pistols at one another. And that was the six- and seven-year olds; the older kids were really tough. I managed to live through two years of Walsh before Pa announced we were moving out. When? I wanted to know. He said he didn’t know, but we would move.

Even at age seven (which is what I was at the time) I knew Pa wasn’t much of a businessman; school supplies and dime novels and such made for a steady, day-to-day sort of income, but nothing more. And while he was a hard worker, Pa had begun to have headaches — what years later might have been called migraines — and there were days when his stall did not open for business. The headaches began, of course, after Mother died.

It couldn’t have been easy for him, but Pa went to Uncle Louis. He went, one Sunday afternoon, to Uncle Louis’ Lake Shore high-rise apartment in Lincoln Park. Uncle Louis was an assistant vice-president with the Dawes Bank now; a rich, successful businessman; in short, everything Pa was not. And when Pa asked for a loan, his brother asked, why not go to my bank for that? Why come to my home? And why, after all these years, should I help you?

And Pa answered him. As a courtesy to you, he said, I did not come to your bank; I would not want to embarrass my successful brother. And an embarrassment is what I would be, Pa said, a Maxwell Street merchant in ragged clothes, coming to beg from his banker brother; it would be unseemly. Of course, Pa said, if you want me to come around, I can do that; and I can do that again and again, until you finally give me my loan. Perhaps, Pa said, you do not embarrass easily; perhaps your business associates, your fancy clients, do not mind that your brother is a raggedy merchant — an anarchist — a union man; perhaps they do not mind that we both were raised by a whorehouse madam; perhaps they understand that your fortune was built upon misery and suffering, like their fortunes.

With the loan, my father was able to start a small bookstore in the part of North Lawndale we knew as Douglas Park, a storefront on South Homan with three rooms in the rear: kitchen, bedroom, sitting room, the latter doubling as my bedroom; best of all was indoor plumbing, and we had it all to ourselves. I went to Lawson school, which was practically across the street from Heller’s Books. And the school supplies Pa sold, in addition to the dime novels he continued to stock, kept his store afloat. In twelve years he’d paid Uncle Louis back; that would’ve been about 1923.

I didn’t know it then, because Pa never showed it, but I was the center of his life. I can see that now. I can see that he was proud of the good grades I got; and I can see that the move we made from Maxwell Street to Douglas Park had mostly to do with getting me in better, safer schools and very little to do with improving Pa’s business — he still wasn’t much of a businessman, stocking more political and economic literature than popular novels (Pa’s idea of a popular novel was Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle), refusing to add the penny candy and junk toys that would’ve been the perfect commercial adjunct to the school supplies he sold, that would’ve brought the Lawson kids in, because the school supplies and dime novels were the only concession he’d make to commerce, the only room he’d sacrifice to his precious books. And he didn’t stock the religious books that would’ve sold well in this predominantly Jewish area, either; a taste for kosher food was about as Jewish as Pa got, and I guess the same has proved true for me. We’re that much alike.

He wanted me to go to college; it was his overriding dream. The dream was no more specific than that: no goal of a son as a doctor, or a lawyer; I could be anything I wanted. A teacher would’ve pleased him, I think, but I’m just guessing. The only thing he made clear was his hope that business — either on Uncle Louis’ high scale or his own low one — would be something I’d avoid; and I always assured him that he needn’t worry about my following either of those courses of action. The only thing I had tried to make clear, since I was about ten years old, was my desire to be a detective when I grew up. Pa took that as seriously as most fathers would; but some kids do grow up to be firemen, you know. And when I kept talking about it on into my early twenties, he should’ve paid attention. But that’s something parents rarely do. They demand attention; they don’t give it. But then the same is true of children, isn’t it?

To his credit, when he gave me the five hundred dollars he’d been saving for God knows how long, he said that it was a graduation gift, no strings, though he admitted to hoping I would use it for college. To my credit, I did; I went to Crane Junior College for two years, during which time Pa’s business seemed to be less than prospering, with him alone in the shop, closing down occasionally because of headaches. When I went back to help him there, he assumed I was working to save up and go on for another two years of college. I assumed he realized I’d decided two years was enough. Typically, we didn’t speak about this and went our merry private ways, assuming the hell out of things.

We had our first argument the day I told him I was applying for a job with the Chicago P.D. It was the first time Pa ever really shouted at me (and one of the last: he reverted to sarcasm and contempt thereafter, the arguments continuing but staying low-key if intense) and it shocked me; and I think I shocked him by standing up to him. He hadn’t noticed I wasn’t a kid, despite my being twenty-four at the time. When he finished shouting, he laughed at me. You’ll never get a job with the cops, he said. You got no clout, you got no money, you got no prayer. And the argument was over.

I never told my father that my Uncle Louis had arranged my getting on the force; but it was obvious. Like Pa said, you needed patronage, or money to buy in, to get a city job. So I went to the only person I knew in Chicago who was really somebody, which was Uncle Louis (never Lou), who was by now a full VP with the Dawes Bank. I went to him for advice.

And he said, “You’ve never asked anything of me, Nate. And you’re not asking now. But I’m going to give you a present. Don’t expect anything else from me, ever. But this present I will arrange.” I asked him how. He said, “I’ll speak to A.J.” A.J. was Cermak, not yet mayor, but a powerful man in the city.

And I made the force. And it was never the same between Pa and me, though I continued to live at home. My role in “cracking” the Lingle case got me promoted to plainclothes after two years on traffic detail; and it was shortly after that that my father put my gun to his head.

The same gun I had used today, to kill some damn kid in Frank Nitti’s office.

3

“So I quit,” I told Barney.

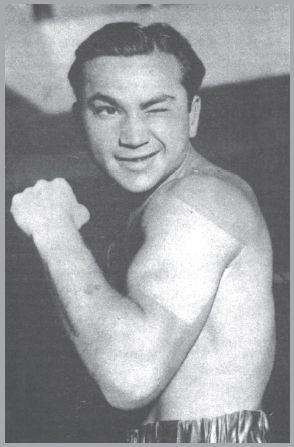

Barney was Barney Ross, who as you may remember was one of the great professional boxers of his time, and that time was now; he was the top lightweight contender in the country, knocking on champion Tony Canzoneri’s door. He was a West Side kid, too, another Maxwell Street expatriate. Actually, Barney still was a kid: twenty-three or twenty-four, a handsome bulldog with a smile that split his face whenever he chose to use it, which was often.

I knew Barney since he was baby Barney Rasofsky. His family was strictly Orthodox, and come Friday sundown could do no work till after Saturday. Barney’s pa was so strict they even ripped toilet paper into strips so the family wouldn’t be tearing paper on the Shabbes. For about a year, when I was seven or eight, right before we moved out of Maxwell Street, I turned on the gas and did other errands for the Rasofskys, as their Shabbes goy, since I was as un-Orthodox as my pa. Later, when I was a teenager in Douglas Park, I’d come back to Maxwell Street on Sundays, to work with Barney as a “puller” a puller being a barker working in front of the door of a store, shouting out bargains supposedly to be found within, often grabbing a passerby and forcing the potential customer into the store. We worked as a team, Barney and me, and Barney was a real trombenik by this time, a young roughneck; so I let him do the pulling, and I handled the sales pitch. Barney had turned into a dead-end kid after his pa was shot to death by thieves in the little hole-in-the-wall Rasofsky’s Dairy. That’s what turned him into a street fighter, and the need to provide for the family his pa had left behind eventually turned him into Barney Ross, the prizefighter.

Barney was smarter than a lot of fighters, but just as lousy with money as the worst of ’em. He’d been pulling in big purses for almost a year now; fortunately, his managers, Winch and Pian, were straight, and got him to make a couple of investments that weren’t at the track. One of them was a jewelry store on Clark; another was a building at Van Buren and Plymouth with a downstairs corner deli next to a “blind pig” — that is, a bar that looked closed down from the street, but was really anything but (lots of things in Chicago looked like one thing outside and something else from inside). Barney planned to call the place the Barney Ross Cocktail Lounge someday, after Prohibition, and probably after he retired from the ring. His managers had a fit when he decided to keep the speak going, because Barney was a public figure in Chicago, with a wholesome image, despite a background that included being a runner for Capone and hustling crap games.

“So you quit,” Barney said. He had a soft, quiet tenor voice, incongruous coming out of that flat, mildly battered puss of his, and puppy-dog brown eyes you could study for days and not see killer instinct — unless you swung at him.

“That’s what I said,” I said. “I quit.”

“The cops, you mean.”

“The opera company. Of course the cops.”

He sipped the one beer he was allowing himself. We were in a corner booth. It was midevening, but slow; the night was just cold enough, the snow coming down just hard enough, to keep most sane folk inside. I only lived a few blocks from here, so was only moderately nuts. None of the other booths were taken and only a handful of stools at the bar were filled.

You went in through a door in the deli and found yourself facing the bar in a dark, smoky room three times as long as it was wide. The only tables were on the small dance floor at the far end, chairs stacked on the little open stage nearby — the nightclub aspect of the joint was on hold till Repeal. Boxing photos hung everywhere, shots of Barney and other fighters, in and out of the ring, with an emphasis on other West Side kids like King Levinsky, the heavyweight, and Jackie Fields, the welterweight Barney used to spar with; and, of course, the great lightweight Benny Leonard, who last year suffered a humiliating defeat attempting a comeback — Jimmy McLarnin put him down in six, giving him a bloody beating (the photos of Leonard on Barney’s wall were from the 1917 championship victory over Freddie Welsh).

“Your pa woulda liked you quitting,” he said.

“I know.”

“But Janey ain’t gonna.”

“That I also know,” I said.

Janey was Jane Dougherty; we were engaged. So far.

“You want another beer?”

“What do you think?”

“Buddy!” he said. He was talking to Buddy Gold, the retired heavyweight who ran the place for him and bartended. Then he looked at me with a wry little grin and said, “You’re throwing money away, you know.”

I nodded. “Being a cop in the Loop is good money in hard times.”

Buddy brought the beer.

“It’s good money in good times,” Barney said.

“True.”

“This Nitti thing.”

“Yeah?”

“It happened yesterday afternoon?”

“Yeah. You saw the papers, I take it?”

“I saw the papers. I heard the city talking, too.”

“No kidding. You serve lousy beer.”

“No kidding. Manhattan Beer, what you expect?” Manhattan Beer was Capone’s brand name; his Fort Dearborn brand liquors weren’t so hot, either. “When did you decide to quit, exactly?”

“This morning.”

“When did you turn your badge in?”

“This morning.”

“It was that easy, then.”

“No. It took me all day to quit.”

Barney laughed. One short laugh. “I’m not surprised,” he said.

The papers had made me out a hero. Me and Miller and Lang. But I came in for special commendation because I was already the youngest plainclothes officer in the city. That’s what having an uncle who knows A. J. Cermak can do for you; that and if you help “crack” the Lingle case.

The mayor was big on publicity. He had a daily press conference; made weekly broadcasts he called “intimate chats,” inviting listeners to write in and comment on his administration; and kept an “open door” at City Hall, where he could be seen sitting in shirt sleeves, possibly eating a sandwich and having a glass of milk, just like real people, any old time — or till recently, that is. Word had it open-door hours had been cut back, so he could better “transact the business of the mayor’s office.”

Today the papers had been full of the mayor declaring war on “the underworld.” Frank “The Enforcer” Nitti was the first major victim in the current war on crime; the raid on Nitti’s office was the opening volley in that war, Cermak said (in his daily news conference); and the three “brave detectives who made the bold attack” were “the mayor’s special hoodlum squad.” Well, that was news to me.

All I knew was when I went to the station after the shooting, I wrote out my report and gave it to the lieutenant, who read it over and said, “This won’t be necessary,” and wadded it up and tossed it in the wastebasket. And said, “Miller’s doing the talking to the press. You just keep your mouth shut.” I didn’t say anything, but my expression amounted to a question, and the lieutenant said, “This comes from way upstairs. If I were you, I’d keep my trap shut till you find out what the story’s going to be.”

Well, I’d seen Miller’s story by now — it was in the papers, too — and it was a pretty good story, as stories went; it didn’t have anything to do with what happened in Nitti’s office, but it’d look swell in the true detective magazines, and if they made a movie out of it with Jack Holt as Miller and Chester Morris as Lang and Boris Karloff as Nitti, it’d be a corker. It had Nitti stuffing the piece of paper in his mouth, and Lang trying to stop him, and Nitti drawing a gun from a shoulder holster and firing; and I was supposed to have fired a shot into Nitti, too. And of course one of the gangsters made a break for it out the window, and I plugged him. Frank Hurt, the guy’s name was — nice to know, if anybody ever wanted the names of people I killed. I was a regular six-gun kid; maybe Tom Mix should’ve played me.

It was a real publicity triumph, made to order for His Honor.

Only I was gumming it up. Today I told the lieutenant I was quitting; I tried to give him my badge, but he wouldn’t take it. He had me talk to the chief of detectives, who wouldn’t take my badge, either. He sent me over to City Hall where the chief himself talked to me; he, also, didn’t want my badge. Neither did the deputy commissioner. He told me if I wanted to turn my badge in, I’d have to give it to the commissioner himself.

The commissioner’s office was adjacent to Mayor Cermak’s, whose door was not open this afternoon. It was about three-thirty; I’d been trying to give my badge away since nine.

The large reception room, where a male secretary sat behind a desk, was filled with ordinary citizens with legitimate gripes, and none of them had a prayer at getting in to see the commissioner. A ward heeler from the North Side went in right ahead of me and, without a glance at the poor peons seated and standing around him went to the male secretary with a stack of traffic tickets that needed fixing, which the secretary took with a wordless, mild smile, stuffing them in a manila envelope that was already overflowing, which he then filed in a pigeonhole behind the desk.

The male secretary, seeing me, motioned toward a wall where all the chairs were already taken.

I said, “I’m Heller.”

The secretary looked up from his paper work as if goosed, then pointed to a door to his right; I went in.

It was an anteroom, smaller than the previous one, but filled with aldermen, ward heelers, bail bondsmen, even a few ranking cops including my lieutenant, who when he saw me motioned and whispered, “Get in there.”

I went in. There were four reporters in chairs in front of the commissioner’s desk; the room was gray, trimmed in dark wood; the commissioner was gray. Hair, eyes, complexion, suit; his tie was blue, however.

He was referring to daily reports on his desk, and some Teletype tape, but what the subject was I couldn’t say, because when he saw me, the commissioner stopped in midsentence.

“Gentlemen,” he said to the reporters, their backs to me, none yet noticing my presence. “I’m going to have to cut this short... My Board of Strategy is about to convene.”

The Board of Strategy was a “kitchen cabinet” made up of police personnel who gathered in advisory session. I wasn’t it, though I had a feeling the commissioner and I were about to convene.

Shrugging, the reporters got up. The first one who turned toward me was Davis, with the News, who’d talked to me more than once on the Lingle case.

“Well,” he grinned, “it’s the hero.” He was a short guy with a head too big for his body. He wore a brown suit and a gray hat that didn’t go together and he didn’t give a shit. “When you going to brag to the press, Heller?”

“I’m waiting for Ben Hecht to come back to Chicago,” I said. “It’s been downhill for local journalism ever since he left.”

Davis smirked; the others didn’t know me by sight, but Davis saying my name had clued them in. But then when Davis wandered out without pursuing it, they followed. I had a feeling they’d be waiting for me when I left, though; Davis, anyway.

I stood in front of the commissioner’s desk. He didn’t rise. He did smile, though, and gestured toward one of the four vacated chairs; his smile was like plaster cracking.

“We’re proud of you, Officer Heller,” he said. “His Honor and I. The department. The city.”

“Swell.” I put my badge on his desk.

He ignored it. “You will receive an official commendation; there will be a ceremony at His Honor’s office tomorrow morning. Can you attend?”

“I got nothing planned.”

He smiled some more; it was a smile that had nothing to do with pleasure or happiness or even courtesy. He folded his hands on the desk and it was like he was praying and strangling something simultaneously.

“Now,” he said slowly, carefully, looking at the badge on his desk out of the corner of an eye. “What’s this nonsense about you... leaving us.”

“I’m not leaving,” I said. “I’m quitting.”

“That is quite ridiculous. You’re a hero, Officer Heller. The department is granting you and Sergeants Lang and Miller extra compensation for meritorious service. The city council, today, voted you three the city’s thanks as heroes. The mayor has hailed you publicly for helping score a major victory in the war on crime.”

“Yeah, it was a great show, all right. But two things fucked it up.”

He squirmed visibly at having the word “fuck” said in his office, and by a subordinate; this was 1932 and school children weren’t using the word at the dinner table yet, so it still had mild shock value.

“Which are?” he said, struggling for dignity.

“First, I killed somebody, and I wasn’t planning to kill anybody yesterday afternoon. Let alone a kid. Nobody seems too concerned about him, though. Nitti’s boys say he has no relatives in the city. Claim he’s from the old country, an orphan. But that’s all they claim; they aren’t claiming the body. That goes into potter’s field. Just another punk. Only I put him there. And I don’t like it.”

The smile was gone now; a straight line took its place, a pursed straight line. “I understand,” the commissioner said, “you weren’t so self-righteous one other time.”

“That’s right. I helped cover something up, and it got me some money and a promotion. I’m from Chicago, all right. But awhile back I decided there’s a line I don’t go over anymore. And Miller and Lang forced me over that line yesterday.”

“You said two things.”

“What?”

“You said two things got... gummed up. What’s the second?”

“Oh.” I smiled. “Nitti. We went up there to kill him yesterday. I didn’t know that, but that’s what we were up there for. And he fooled all of us. He didn’t die. He’s in the hospital right now, and it’s beginning to look like he’s going to pull through.”

Nitti had been taken to the hospital at Bridewell Prison, but his father-in-law, Dr. Gaetano Ronga, had him transferred to Jefferson Park Hospital, where Ronga was a staff physician. Ronga had already issued statements to the effect that Nitti would live, barring unforeseen complications.

The commissioner stood; he wasn’t very tall. “Your allegations are unfounded. The address at the Wacker-LaSalle Building was believed to be the headquarters for the old Capone gang, now under Frank Nitti’s leadership.”

“It was a handbook and wire room.”

“An illegal gambling den, yes, and in the course of your raid, Frank Nitti pulled a gun.”

I shrugged. Got myself up. “That’s the story,” I said.

“Keep that in mind,” the commissioner said. There was a tremor in his voice; anger? Fear.

“I will,” I said.

I turned and headed out.

“You’ve forgotten something.”

I glanced back; the commissioner was pointing to my badge, where I’d laid it on his desk.

“No I didn’t,” I said, and left.

“So what’s bothering you?” Barney said. “Killing some innocent kid?”

I sipped at my third beer. “Who’s to say he was innocent? That isn’t the point. Look. I held on to this goddamn thing” — I patted under my arm, where the automatic was — “because my father blew his brains out with it. Anytime I take it out of its harness, somewhere in my brain I keep the thought of that. So that I won’t take using it lightly. Only I did use it, didn’t I?”

“Yeah.” He patted my drinking arm. “But you ain’t takin’ it lightly.”

I found a smile. “I guess not.”

“So where do you go from here?”

“To all one rooms of my apartment. Where else?”

“No, I mean, what kind of trade you gonna take up?”

“I only got one trade. Cop. For what it’s worth.”

We’d talked about it plenty of times, Barney and me. That one day I’d quit the department and open my own agency. I’d talked about it with my friend Eliot, too; he’d encouraged me to do it, said he’d help line some business up. But it had always been a pipe dream.

Barney stood up and got a funny little smile going, a little kid smile, and motioned with a curling forefinger. “Come with me,” he said.

I just sat there with half a beer in my hand, giving him a “what the—” look.

He grabbed me by the coat sleeve and tugged till I got up and followed him, back through the deli and out onto the street, where the snow had stopped and the city had got quiet, for a change. There was a door between the blind pig and the pawnshop next door. Barney searched for keys, found some, and unlocked the door. I followed him up a flight of narrow stairs to a landing, and then did that two more times, and we were on the fourth floor of his building, which ran mostly to small businesses, import/export, a few low-rent doctors and lawyers and one dentist. Nothing fancy, certainly. Wood floors, glass-and-wood office walls, pebbled glass doors.

At the end of the hall the floor dead-ended in an office that bore no name. Barney fished for keys again and opened the door.

I followed him in.

It was a good-size office, cream-color plaster walls with some wood trim, sparsely furnished: a scarred oak desk with its back to the wall that had windows, a brown leather couch with some tears repaired by brown tape, a few straight-back chairs, one in front of the desk, a slightly more comfortable, partially padded one behind it. The El was right outside the windows. It was a Chicago view, all right.

I ran a finger idly across the desk top. Dusty.

“You can find a dustcloth, can’t you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, it’s your office. Leave it filthy if you want.”

“My office?”

“Yeah.”

“Don’t go meshugge on me, Barney.”

“Don’t go Yiddish on me, Nate. You can’t pass.”

“Then don’t go Jewish on me when you tell me the rent.”

“For you, nothing.”

“Nothing.”

“Almost nothing. You gotta live here. I can use a night watchman. If you ain’t gonna be here some night, just phone in and I’ll cover for you somehow.”

“Live here.”

“I’ll put a Murphy bed in.”

He opened a door that I thought was a closet. It wasn’t. The office had its own washroom: a sink, a stool.

“Not all the offices have their own can,” he said, “but this was a lawyer’s office, and lawyers got a lot to wash their hands over.”

I walked around the room, looking at it; it was kind of dingy-looking. Beautiful-looking, is what it was.

“I don’t know what to say, Barney.”

“Say you’ll do it. Now, in the morning, you want a shower, you walk over to the Morrison.”

The Morrison Hotel was where Barney lived. They had a traveler’s lounge for regular patrons who were in town for the day and needed a place to freshen up or relax — sitting rooms, shower stalls, exercise rooms — one of which had been converted into a sort of mini-gym by Barney, with the hotel’s blessing.

“I’ll be working out there most mornings,” Barney continued, “and at the Trafton gym most afternoons. You’re welcome both places. I’m training, you know.”

“Yeah, somebody’s got to pay for all this.”

Barney was known for being a soft touch: a lot of the guys from the old neighborhood had taken advantage of him, hitting him for loans of fifty and a hundred like asking for a nickel for coffee. I didn’t want to be a leech; I told him so.

“You’re makin’ me mad, Nate,” he said expressionlessly. “You really think it’s smart to make the next champ mad?” He struck a half-assed boxing pose and got a laugh out of me. “So what do you say? When do you move in?”

I shrugged. “Soon as I break it to Janey, I guess. Soon as I see if I can get an op’s license. Jesus. You’re Santa Claus.”

“I don’t believe in Santa Claus. Unlike some people I know, I’m a real Jew.”

“Yeah, well drop your drawers and prove it.”

Barney was looking for a fast answer when the El rumbled by like a herd of elephants on roller skates and provided him with one.

“No cover charge for the local color,” he said, speaking up.

“Don’t you know music when you hear it?” I said. “I wouldn’t take this dump without it.”

Barney rocked on his heels, smiling like a kid getting away with something.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said, trying not to smile back at him, “before I start dusting.”

“Nightcap?” Barney asked.

“Nightcap,” I agreed.

I was having one last beer, and Barney, staying in training, was just watching, when a figure moved up to the booth like a truck parking.

It was Miller; the eyes behind the Coke-bottle glasses looked bored, half-asleep.

“How’s the fight racket, Ross?” Miller asked, in his off-pitch monotone, hands in his topcoat pockets.

“Ask your brother,” Barney said, noncommitally. Miller’s brother Dave, also an ex-bootlegger, was a prizefight referee.

Miller stood there for a while, his capacity for making small talk exhausted.

Then moved his head in a kind of sideways nod, toward me, and said, “Come on.”

“What?”

“You’re coming with me, Heller.”

“What is it? Visiting time at Nitti’s hospital room? Go to hell, Miller.”

He leaned over and put a hand on my arm. “Come on, Heller.”

“Hey, pal, this is where I came in.”

Barney said, “I’m going to land you on your fat ass, Miller, if you don’t take your hand off my friend.”

Miller thought about that, took the hand off, but out of something closer to boredom than fear from Barney’s threat.

“Cermak wants to see you,” he said to me. “Now. Are you coming, or what?”

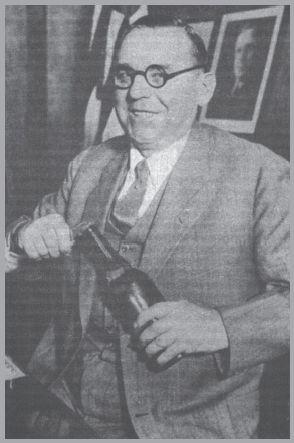

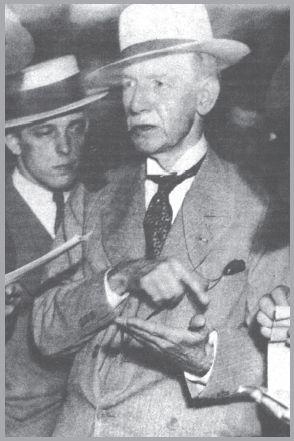

Mayor Cermak

4

I’d never spoken to Mayor Cermak, but I’d seen him before; almost every cop in Chicago had. His Honor liked to pull surprise personal inspections on the boys in blue and then carry his criticisms to the press. He claimed he wanted to weed the deadweight out of the department, to cut down on the paperwork, to have a maximum number of men out on the streets at all times, battling crime. All this from a mayor with the behind-his-back nickname Ten Percent Tony, whose political life seemed a study in patronage; who as Cook County commissioner (a position also known as “mayor of Cook County”) had given Capone free reign (well, not exactly “free”) to turn the little city of Cicero into gang headquarters, with it and nearby Stickney becoming the wettest of the wet in this dry land, as they were simultaneously overrun with slot machines, whores, and gangsters. Cook County, where two hundred roadhouses had been personally licensed by Tony; where Capone dog tracks flourished thanks to an injunction by a Cermak judge; where Sheriff Hoffman permitted bootleggers Terry Druggan and Frankie Lake to leave his jail most anytime they pleased, and they consequently spent more time in their luxurious apartments than behind bars, though Hoffman eventually landed behind bars himself — for thirty days — after which Cermak gave him a post with the forest preserves at ten grand per annum; and, well, all this “reform” talk coming from Cermak sounded like a crock of shit to most Chicago cops.