Max Allan Collins

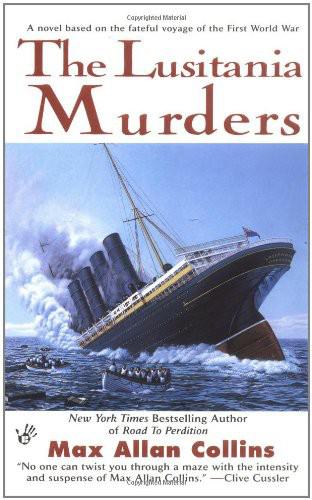

The Lusitania Murders

“There’s been some cover-up about the Lusitania. .

it was really murder.”

“There are few punishments too severe for a popular novel writer.”

“So long as governments set the example of killing their enemies,

private citizens will occasionally kill theirs.”

“NOTICE!

Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on ships of Great Britain or her allies to do so at their own risk.

Imperial German Embassy

Washington, D.C., 22 April 1915”

Announcement appearing in New York newspapers the morning the Lusitania sailed

ONE

Dinner at Luchow’s

My friend H.L. Mencken-at least, from time to time we were friends-once characterized me as the “biggest liar in Christendom.” So I would take no offense if the gentle reader (as Elbert Hubbard would say) discounted the tale I’m about to tell, as typical S.S. Van Dine self-aggrandizement.

On the other hand, over the years, the question I’ve most often been asked is how I came up with my distinctive pseudonym. The “Van Dine,” I have explained, is simple: It is an elegant representation of my occasional desire to eat, a luxury that requires earning the more than occasional dollar. Some have speculated that the “S.S.” represented the traditional abbreviation of “steamship,” which is in part true, and relates to this tale, taking place as it does on one of the most famous-and infamous-ocean liners of the twentieth century.

Like most artists, however, I have an irresistible inclination toward resonance-double meanings and second levels. And while it is true that I regard my mystery novels as voyages of entertainment, “vacation reading” that encourages my patrons to board the S.S. Van Dine for a good trip, that “S.S.” did indeed have a secondary shade of significance, which at the time seemed clever and now merely strikes me as (I shudder to admit) cute.

At the time of my ill-fated voyage on the Lusitania, I was in no position to travel first class; frankly, managing the fare for second class would have been a trial, and even steerage a stretch. In March of 1914, a year and two months prior, I had suffered through the indignities of second class; the food, accommodations and company were of a different order than my trip to Europe the previous spring, as editor of The Smart Set.

My brother Stanton-the eminent Modernist painter who pioneered the Synchromist movement-was living in London in early 1915. I had spent almost a year with Stanton in Europe-first in Paris, then London-before returning on the Olympia in March, leaving him to stubbornly serve his muse.

Our sojourn in Europe had been well-intentioned-Stanton sought a suitably sympathetic climate in which to paint, I to pursue writing (both criticism and fiction)-but in retrospect our timing could have been better. A continent withered by war and gripped by nationalist hysteria was hardly conducive to creativity.

In April of 1915 I began to cast about for a way to return to Europe, and convince Stanton to return stateside. But the condition of my finances-and, frankly, of my health-was less than ideal.

In some respects, though, my life was on the upswing. I had received a modest advance for my book-in-progress, Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning, and fees for essays and reviews for various publications, Forum and International Studio among them, allowed me to move from my dismal flat in the Bronx to a two-room apartment over a store on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. Disagreeably dilapidated though the building might be, the thirty-five dollars a month rent was friendly enough.

In addition, after a debilitating illness,* my health had recently improved. For months I had been weak and on edge, filled with hallucinations and phobias, and would surely have checked myself into a hospital if my monetary status had allowed. Instead, I ministered to myself in a singularly unromantic garret-a boardinghouse room in the Bronx-until I looked healthier and less drawn, and could come out among the civilized once again.

Perhaps a certain illness-induced gauntness emphasized my already Mephistophelian features-the receding nature of a reddish-brown hairline emphasized my intellectual stance, even if the former aspect was underscored by the devilish glint in my blue eyes and the spade-shaped if well-trimmed full beard, the upturned corners of my mustache perhaps hinting at my pro-German leanings.

Well over a decade later, my Germanophile’s view might seem harmless enough; on the eve of what would be the Great War, I suffered numerous negative repercussions, due to what I admit was an intellectual’s naivete. It seemed to me that reasonable men could tell the difference between Wagner and Kaiser Bill; that a mind fond of Mahler, Strauss, Goethe and Mann did not signify an insurgent heart.

This pro-German stance-added to my reputation as a prolific if outspoken columnist, with the boost of an H.L. Mencken recommendation-had brought me to this table. Of course it could also be said that Gavrillo Princzip made inevitable this appointment, when-on June 28, 1914, on a Sarajevo, Serbia, street-he shot and killed the Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

As a bonus, Princzip had also killed the archduke’s wife, and this rash act (the archduke’s assassination, that is, not Mrs. Archduke’s) served to spark a war involving Russia, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France and Great Britain. Ten million lives would be lost, twenty million souls would be wounded and twenty-five million tons of shipping would be sunk.

But the war was three thousand miles away, on this warm Friday evening in Manhattan in late April of 1915; the three of us were in a bustling Bavarian restaurant near Union Square, on Fourteenth Street. Perhaps the city’s best-known German restaurant, Luchow’s-with its dark woodwork and baroque dining rooms with their elaborate gilt-framed landscape oils and solemn looming stags’ heads-found its popularity unswayed by a growing anti-German sentiment, and remained a favorite haunt of writers, musicians and theater folk. Tonight I was dining at the invitation of publishing legend Samuel Sidney McClure and one of his associates, Edward Rumely.

We were seated at a table beneath the Wagner murals in the Niebelungen Room; I had my back to the eight-piece orchestra, which had been brought to this country by Victor Herbert, whose mediocre music they performed with all the lack of panache it deserved. Fortunately the din of dinner conversation all but drowned out the orchestra’s brainlessly lilting aural wallpaper. We were drinking beer from steins, having completed our prime beef and red cabbage.

McClure was a stern-looking character, with a short blunt nose and a carelessly trimmed white mustache, his blue eyes piercing in an almond-oval face topped with a shock of gray hair; a thought-gouged crease between his eyes suggested eternal skepticism. His brown vested suit with darker brown bow tie might have been the attire of a chief clerk, not the man who invented newspaper syndication, and whose McClure’s Magazine had taken on corruption in corporations and city government.

After all, the term “muckraker” had been coined to describe McClure’s efforts, which included publishing Lincoln Steffan’s “Shame of Our Cities” series and blistering exposes on Standard Oil and the United Mine Workers.

The third and final member of our little all-male dinner party was a thickset fellow in his mid-thirties who looked rather like a bulldog in a three-piece suit, a navy suit as rumpled as its wearer’s homely face. This was Edward Rumely, the owner and publisher of The New York Evening Mail, a recent acquisition of this scion of the Rumely farm implement manufacturing clan. The family wealth may have derived from diesel farm equipment, but Edward Rumely had other ideas about making his own fortune. . in publishing.

“I understand congratulations are in order,” I said to McClure, and then lifted my stein in an informal toast toward the vested bulldog. “To both of you-for your new position, Mr. McClure, and for landing such a prestigious editor for the News, Mr. Rumely.”

“You may not be aware, sir,” McClure said to me, his voice a gruff baritone, “that I’ve lost control of my own magazine. . to my ‘loyal’ partners, and various investors.”

“I had not been so informed,” I said. But I did know that S.S. McClure’s reputation was that of a man of innovative, grandiose ideas. . who lacked in business sense.

“Part of the buyout of the magazine that still bears my name,” McClure said, “is a ten-year noncompetition clause.”

“That applies to magazines,” Rumely put in, in his knife-blade tenor, “not to newspapers. . Meaning I’ve bagged one of the biggest names in publishing to edit the News.”

The line between McClure’s eyes tensed-the bluntness of Rumely’s expression understandably offended him.

“If I’m not overstepping,” I said, “surely you don’t need to work, Mr. McClure. . ” He was approaching sixty and most certainly was comfortably wealthy.

“I want to work, sir,” McClure said. “I need to work. Money has never been my objective-communicating progressive ideas to the public, that, sir, is my calling.”

“I understand the impulse,” I said. “I’ve hoped to educate the unwashed masses myself. . not in political areas, where I admit a certain lack of knowledge and even interest. But in the arts-painting, literature.”

“That’s why we’re considering you,” McClure said, “for our literary editor.”

“Book reviews, short essays,” Rumely explained, “publishing announcements, gossip. . ”

In those days, “gossip” meant reporting the books writers were working on, or travels they might be taking for research purposes-not peccadilloes, sexual or otherwise.

“I’m the man for the job,” I said with no modesty. “I feel an affinity with you, Mr. McClure-in our shared desire to make a difference in the world. If I could persuade readers to turn from romance novels to Joseph Conrad, if I could move them to protest censorship, as pertains to Dreiser and others-”

“All well and good, sir,” McClure cut in. “But you have a reputation for a sharp tongue-for sardonic, even sarcastic condescension.”

“Guilty,” I said with a shrug.

“I would not censor you, but I would insist that you strive to abandon any mean-spiritedness in your psyche.”

“I was younger then,” I said, referring to my controversial tenure at a Smart Set, as well as my biting Los Angeles Times writings, which had put me on the map.

McClure’s eyes appraised me unblinkingly. “How old are you, sir?”

“Thirty-three,” I said.*

He nodded, obviously glad to hear I was no longer a young pup. “This Lusitania voyage will be a test of your new maturity, then.”

“I consider it a golden opportunity, Mr. McClure.”

“Your journalistic sense of fair play will be tested.”

“How well I know it. I wrote a fairly vicious piece on Hubbard in Smart Set.”

The homespun philosopher Elbert Hubbard was booked on the Lusitania; I was to ingratiate myself with him and do “the definitive interview” with the so-called “Sage of East Aurora” (New York). That I considered him a boob and a fraud apparently was not to get in the way of this non-mean-spirited effort.

“Though you’ve written of him,” McClure said, “you have never met Hubbard. .?”

“I’ve been spared that pleasure thus far.”

McClure’s eyes tightened. “You should understand that I admire Elbert Hubbard-consider him a sort of roughhewn genius. . and I’m not alone. Clarence Darrow, Henry Ford, Booker T. Washington, even Teddy Roosevelt, have sat looking up at him.”

Which only meant that even the best among us have our foolish streaks.

“Impressive,” I said.

“Keep an open mind, sir. And do your best not to alienate your subject.”

To McClure, Rumely said, “That’s why we’ve arranged for our friend here to travel under a pseudonym. His true identity is known by Staff Captain Anderson, and he will of course carry a proper passport to present at journey’s end, in Liverpool.”

McClure was frowning, the line between his eyes like an exclamation point. “I dislike such deceptions.”

“Modern journalism requires bold methodology,” I opined. “If I were to travel under my own name, Hubbard would surely recognize it, and never grant me an interview.”

“Several of the other prominent passengers,” Rumely put in, “might react similarly, if they happen to know of our man’s acid reputation.”

McClure said to Rumely, as if I were not present, “Is he aware of the other potential interviewees?”

“I thought we would discuss that after you’ve taken your leave, Sam,” Rumely said.

McClure had already announced that his attendance at our little gathering would be abbreviated, as he was meeting with his wife and a group of theater-goers to attend D.W. Griffith’s new moving picture, Birth of a Nation, at the Liberty Cinema on Forty-second Street. It was said the show elevated that nickelodeon novelty to the level of art-which I sincerely doubted, though I did relish the thought of the theater’s new cooling system, as stifling summer months lay ahead.

“Just so we understand each other,” McClure said, his hard gaze travelling from Rumely to me. “I suppose you know that I consider myself a Progressive.”

“I do,” I said, and I did-from backing Teddy Roosevelt to extolling the virtues of health foods, McClure was if anything a freethinker.

“So is my friend Edward here,” McClure went on, and placed a hand on the bulldog’s shoulder. “We share many interests. . We met when my son was attending the Montessori school Edward ran for a time in LaPorte, Indiana. . Edward agrees with my current campaign, for example, to form an international organization that would guarantee peace among all nations, world round.”*

“How interesting,” I said, not really caring. Politics were anathema to me.

“You see, my sympathies in the current struggle are with Great Britain. . and Edward’s are with Germany. As reasonable men who can agree to disagree, we have struck a bargain-the News will air both points of view, but ban the propaganda of both.”

“I wish more newspapers would take a neutral position on the war,” I said. “I’m appalled by these crude British-slanted atrocity stories-Belgium children mutilated, women raped, shopkeepers murdered. . tasteless rabble-rousing trash.”

“I agree wholeheartedly,” McClure said. “But I will not tolerate a pro-German point of view, either. . is that understood, sir?”

So that was the real heart of tonight’s matter.

“I will take the same neutral stance as the News,” I assured him.

He took a final sip from his stein. Too casually, he said, “I have learned that a book of yours is about to be published.”

I shifted in my chair. “That is true.”

“The Teachings of Nietzsche? Huebsch is bringing it out, I take it.”

“Actually, sir, it’s entitled What Nietzsche Taught. . and much in your tradition, I seek only to guide the general reader to a better understanding of an important philosopher’s much-maligned, much-misunderstood writings.”

He dabbed a napkin at himself, cleansing his mouth and mustache of beer foam. “There are those who say Nietzsche is to blame, in some degree, for this war-that he was the Prophet of the Iron Fist and the Teutonic Superman. . the enemy of common, decent people.”

“Which is why my book is so important, Mr. McClure. Nietzsche wasn’t interested in the acquisition of land for the state, or glory for the Kaiser. . but in each man’s ability to find within himself strength, confidence, exuberance and affirmation in life. . a life intensified to its highest degree, charged with beauty, power, enthusiasm. . ”

I didn’t realize it, but I was sitting forward now, my voice raised somewhat, and what seemed at first an awkward silence followed. . until McClure’s grim countenance broke into an unexpected grin.

“I like the sound of that,” he admitted. “And I like your spirit. . and your mastery of the English language.” He gathered his coat and hat, stood and offered me his hand, which I shook. He shook hands with his publisher, and then pressed through the bustle of waiters and patrons, on his way to see D.W. Griffith’s eighteen thousand actors and three thousand horses.

We didn’t even have time to rise, and Rumely smiled on one side of his rumpled face, rumpling it further, saying, “He’s a rather brusque fellow, our McClure.”

“Yes,” I said. “But I do admire his frankness.”

“Shall we have the Luchow’s fabled sliced pancakes?”

“Certainly.”

And we did. While we ate them, my squat companion pointed out a sort of celebrity to me-a stocky, square-jawed man in his sixties, wearing an unprepossessing black suit with string tie and a bowler hat which he left on while he ate at his solitary table.

“That’s the captain of the Lusitania,” Rumely said. “Bowler Bill himself.”

“That’s this Anderson I’m to check in with?”

“No. Turner’s the captain, the top man, but his second in command, Staff Captain Anderson, really runs the ship. Turner’s an old salt some say is past his prime. . bit of a martinet, a taciturn type who dislikes socializing with the passengers.”

“But doesn’t that come with the job?”

“It does, and you’ll see him from time to time-but Anderson will be your contact. The Cunard people themselves recommended we deal with him.”

“We have their full cooperation?”

“Oh yes,” Rumely said, and there was something sly in that smile into which he was currently shoveling pancakes, and a twinkle in his eyes that wasn’t fairy-like. “We have their full cooperation for a fine set of articles-pure puffery about their famous passengers.”

I was willing to write such tripe, particularly under a pseudonym. One’s pride takes second place to the need for nutrition. In recent months I had, for the first time, lowered myself to the hackwork of popular fiction writing, churning out made-to-order adventure stories for pulp magazines. I had even “novelized” (what an abhorrent word) a putrid play, The Eternal Magdalene, into a passably literate work.

After the pancakes came snifters of Courvoisier. The sweetness of the dessert didn’t really suit this follow-up, but I could never resist that particular cognac, even when ill-advisedly served.

“Who else besides the estimable Hubbard will feel the feathery brunt of my pen?” I inquired.

“Well, you’ll be rubbing shoulders with some interesting passengers, there in Saloon.”

“Saloon Class” was the Cunard line’s designation for first class. . ah, first class. . if one were to be a prostitute, let it be on a soft mattress between sweetly-scented sheets. .

“After Hubbard,” Rumely said, “your prime candidate will be Alfred Vanderbilt. . probably the richest man on earth.”

“I’ll offer to take his suits to the ship’s cleaner for him,” I said. “Perhaps a million or two will turn up in his pockets.”

The owner of the restaurant, August “Augy” Luchow-a robust gentleman whose considerable girth was matched only by his bonhomie and perhaps his handlebar mustache-was making a fuss over Captain Turner.

Rumely said, “This Madame DePage-have you read of her?”

I sipped my snifter, tasted the cognac, let its warmth roll down my gullet. “The Belgium relief fund woman? She’s been too conspicuous in the press to miss, even for an apolitical lout like myself. Is she travelling the Lusitania?”

“Yes, she and the one hundred fifty thousand dollars in war relief cash that she’s raised in recent weeks. Her motives seem sincere-she could rate a good human-interest piece.”

“Anyone else?”

“Frohman’ll be aboard. He’s always good for a story. People love show business, you know.”

Charles Frohman was the leading theatrical producer of the day-the man who brought Peter Pan to the stage, and Maude Adams to Peter Pan.

Rumely handed me a manila envelope. “There are your tickets and other materials-using the pseudonym you requested. Is the ‘S.S.’ a reference to steamship, or to Mr. S.S. McClure, your benefactor?”

“Both,” I said. “As for Van Dine, I believe it suggests in an elegant manner the less than elegant need for nourishment.”

The bulldog smiled. “Another Courvoisier?”

“Certainly. And is there anything else we need to discuss, where business is concerned?”

Rumely seemed almost taken aback. “Why, certainly-you don’t think I sought you out to merely do the conventional bidding of my editor.”

“Well, I-”

The publisher held up a stubby hand. “We’ll have another round of cognacs, and then I’ll tell you.”

“Tell me what?”

He chuckled. “Why, the real reason you’re boarding the Lusitania tomorrow, of course. . Waiter!”

TWO

The Big Lucy

Before we get on with the tale at hand, in order to illuminate the nature of various deeds (dastardly and daring), some background seems advisable, regarding the Cunard steamship line’s unusual partnership with the British government.

By the time the nineteenth century dragged itself reluctantly into the twentieth, German liners had become the standard for speed and luxury, which offended the sensibilities of Great Britain, that self-proclaimed “greatest seafaring nation on earth.” Further, collusion between J.P. Morgan (whose White Star Line was Cunard’s greatest rival) and various non-British lines (including Holland-Amerika) set the stage for domination of North Atlantic tourist trade by the upstart American line and its foreign business allies.

Lord Inverclyde, chairman of Cunard, invoked patriotic pride to convince the British government to lend the line better than two and a half million pounds for the building of a pair of new ships designed to restore Cunard-in terms of both speed and luxury-to a position of pre-eminence in the North Atlantic. Those ships, the sisters Mauretania and Lusitania, were in effect co-owned by the British government.

For this reason, the Lusitania was designed-its sister, too-for a dual purpose: Decks bore gun emplacements, coal bunkers ran along the sides of the hull to protect boilers from shells and deep storage spaces were fashioned for easy conversion into magazines. In effect, the Lusitania was a luxury liner ready to metamorphose into a battleship.*

This blurring, between commerce and combat, must be understood for the Lusitania’s tale to make any sense at all. . if such is possible.

Sailing day for the Lusitania was the first of May, 1915, a drab, drizzly Saturday. All sailing days were bustling affairs, what with the processing of hundreds of passengers, and thousands of pieces of luggage to be lugged aboard and stored. But any time the Lusitania set sail (if that phrase could be loosely applied to a mighty turbine-powered ship), a throng could be expected dockside, though she had tied up there more than a hundred times, and was a familiar sight at the foot of Eleventh Street. New Yorkers had embraced the Big Lucy ever since that day, eight years before, when she had docked here upon completion of her maiden voyage; even the stench of the nearby meatpacking district couldn’t keep them away.

And indeed an even larger than usual crowd had braved the growling gray sky and the sticky spring drizzle to cluster along cement-fronted Pier 54 with its massive green-painted sheds blotting out the Manhattan skyline. This was in part because an uncommon number of Americans would be boarding the Lusitania today, many of them women in second class and steerage-wives on their way to join soldier husbands, and nurses who had volunteered to work with the Red Cross.

But the primary reason for the dockside swarm of what might loosely be termed as humanity related to a warning from the German embassy that had appeared in virtually every New York newspaper either last night or this morning. In some of the papers, this warning had appeared side by side with Cunard’s advertisement announcing the sailing of the Lusitania today at noon.

This notice had warned travellers “intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage” that “a state of war exists between Germany and Great Britain”; and that the war zone included the waters adjacent to the British Isles. It went on to remind would-be travellers that should they board “vessels flying the flag of Great Britain,” they did so at their own risk.

Because of this, a fair share of walleyed rubberneckers had come out for a morbid good time, and a gaggle of hardboiled reporters and photographers, including newsreel cameramen, had converged upon Pier 54. Sidewalk photographers were taking shots of the looming ship with assistants yelling, “Last voyage of the Lusitania!” and taking down orders. Like a grotesque parody of a Broadway opening night, wide-eyed faces bobbed in the crowd to the discordant tune of burbling chatter and inappropriate laughter. Added to this were the smells of sea and oil, almost dispelling the meatpacking reek, and the sounds of a colossal ship coming to life.

As I stood dockside with my bulldog of an employer, Rumely, I was struck like a schoolboy by the immensity of the hull and the four funnels that reached higher up than my neck could crane back. And looking from left to right, one’s field of vision was consumed by a black field of steel with an army of rivet heads lined up in orderly ranks.* Normally the great ship would have been festooned with flags; but today, under clouds of war, even the brass letters on the bow were painted black, and the formerly scarlet and black funnels were simply black now, to make enemy identification harder.

Impressive as the Lusitania was, one could hardly deem her a beautiful ship-one man’s tour de force in naval architecture was another’s aesthetic monstrosity. From her ventilator-strewn superstructure to those colossal ungainly funnels, the Lusitania was at once the largest movable object yet built by Man. . and one of the most maladroit-a top-heavy study in ponderous bulk lacking the slim grace of the Olympic (and her fallen sister, Titanic).

“There seems to be a bit of a delay,” Rumely said. His broad brow was flecked with sweat; the morning was as warm as it was damp, and his three-piece gray tweed suit was a poor choice for the time of year.

I wore a gray homburg and a crisply new three-piece light blue suit, part of the spiffy wardrobe the News had sprung for me, to help me fit in with the nobs. I stroked the drizzle off my beard. “Why is that?”

“I understand the Lucy is taking on extra passengers from the Cameronia.”*

“Overflow?”

“No-the British Admiralty has requisitioned her. . It’ll probably amount to several hours, at least. Do you want to go on aboard?”

I shook my head. “I prefer to maintain my ringside seat, and allow those lines to thin themselves out. That way you can point out my interview subjects, in case the photographs you provided don’t do them justice.”

“Don’t be alarmed by this elaborate boarding procedure,” Rumely said, nodding toward the three separate lines leading to three separate gangways (for Saloon Class, Second Cabin and Third Class) where all the passengers and their baggage were being carefully inspected.

“I’m sure the documents you gave me will do quite nicely,” I said. “And if they don’t, you’ll bail me out of the pokey.”

Rumely frowned at my levity. “I hope you appreciate the seriousness of your mission.”

“I do, I most certainly do.” Actually, what I appreciated was the one-thousand-dollar bonus that Rumely had promised me for taking his sub-rosa assignment.

Pinkerton men and U.S. Immigration officials aided Cunard staffers in what was obviously a serious security effort. Pursers at tables screened each passenger and said passenger’s luggage, then marked them (the luggage, not the passengers) with chalk before Cunard deckhands in starched white sport jackets carried the bags aboard.

Still, for all of this-and the carnival-like hawking of “final” photos and little British flags on sticks, and the handing out of leaflets quayside by men warning against travel-the passengers who had run the security gauntlet, and were now sauntering up the gangways, seemed happy and at ease. Why should the war interfere with their travel plans? Wars were, after all, the enterprise of armies-soldiers took the battlefields, while politicians negotiated, and civilians stood on the sidelines.

I was aware, however, that the passengers boarding the Big Lucy were at least as naive in the ways of politics as I was-or at least as I had been, prior to signing on as Edward Rumely’s journalistic spy.

The evening before, after S.S. McClure had left us alone, Rumely had informed me that I had been chosen for this job because of my pro-German sympathies. I had explained that while I considered Germany a diverse and culturally progressive modern state-and not the British-concocted caricature of the press-I had no interest in politics.

And Rumely had only smiled and said, “Well, I am content that you are, at least, aware of the preponderance of British propaganda, and the need for balance.”

I really wasn’t interested, but he was picking up the check, so I said, “That’s certainly true.”

“Are you aware of the recent scandal on the very pier from which you’ll be sailing?”

I admitted I was not, and Rumely, in some detail, told of German cargo ships that were trapped in port by British ships lying in waters outside the three-mile zone. In violation of President Wilson’s neutrality proclamation, a group had been supplying food and fuel to those British ships.

“I have credible reports,” Rumely told me, “that the Cunard line itself is involved in this criminal effort.”

“Really,” I said, and tried to put some indignation into it.

“Further reports indicate that the Cunard line is using its passenger liners to transport contraband-including ammunition, weapons and perhaps even high explosives.”

“Mr. Rumely, that would seem patently ridiculous-the Lusitania is a passenger ship, not a freighter. .”

“Exactly why Cunard hopes she will be given a free pass by German U-boats. And there are other reports that the Lucy is heavily armed-three- or possibly even six-inch guns.”

“Wouldn’t these be apparent?”

“Not if they were effectively disguised in some fashion.”

I was beginning to see what Rumely expected of me. “You’d like me to ascertain whether these big guns exist. . and whether guns and ammunition are secreted away in the cargo hold.”

“Exactly. . and, of course, you must conduct the interviews Mr. McClure has requested.”

“And how will Mr. McClure react if I come back with a story of American collusion with the British in smuggling contraband through the war zone?”

Rumely’s expansive face expanded further in a wide smile. “For all his pro-British leanings, he will be delighted-he made his reputation on publishing exposes. You, of course, will have stumbled upon these facts innocently, in the course of pursuing your shipboard interviews.”

I said nothing; the likelihood of arranging an interview with Alfred Vanderbilt in a cargo hold seemed distant, but the promise of a trip to Europe to fetch my brother-plus a handsome check-made mentioning this seem imprudent.

Now Rumely and I were dockside, well-positioned to watch as reporters buttonholed prominent passengers who waited in the security line, the war threat having temporarily made equals out of all men. One of those queued up was, in fact, Alfred Vanderbilt himself. . travelling with a valet but without his wife or other family members. Judging by the familiarity of their conversation, Vanderbilt and the slender fellow in line behind him were friends.

In what I would take to be his mid-thirties, Vanderbilt had a handsome oval face characterized by thick dark eyebrows and a dimpled ball of a chin. The slightly built multimillionaire presented a breezy appearance in his charcoal pin-stripe suit, blue polka-dot foulard bow tie and jaunty tweed cap.

The reporters pelted him with questions about the danger of taking this voyage, and he laughingly replied, “Why worry about submarines? We can outdistance any sub afloat.”

“Is this trip business or pleasure, sir?” one reporter called.

“I’m attending a meeting of the International Horse Show Association. And that’s all I have to say, gents.”

While Vanderbilt was known to be happily married (to his second wife), he had long been a popular figure at sporting events; but some said his love for fast horses, and fast cars, was matched by a fondness for fast women. It was no surprise that these reporters might assume the European trip would include discreet appointments that were not exclusively with horse breeders.

“You’ll have your work cut out for you with that one,” Rumely said. “Alfred doesn’t like to talk to reporters. He’s had some unhappy experiences with the press.”

Before long the reporters were descending on a squat, even frog-like figure in a black double-breasted suit with a stiff collar and dark felt hat; he leaned on a cane, which made him seem even shorter. Something in the cheerful expression on his moon face appeared forced-was he in pain, I wondered?

“That’s Charles Frohman,” Rumely said, but I had already guessed as much.

This was the legendary Broadway producer, the so-called “Napoleon of the Drama.” I put him at around sixty years.*

“What’s wrong with him?” I asked Rumely.

“Articular rheumatism. He had a bad fall, some time ago, and has never been the same since. Yet he makes these pilgrimages to London, twice a year.”

A reporter was asking, “Are you afraid of the U-boats, Mr. Frohman?”

The producer grinned, a pleasant smile on an ignoble face. “No-I only fear IOU’s.”

Another reporter called, “Going to check out the current crop of West End productions, sir?”

“Yes-in particular, Rosy Rapture at St. Martin’s Lane-we’ll see if it’s Broadway material.”

Another chimed, “Is it true you’ve secretly married Maude Adams?”

He seemed genuinely embarrassed as he shook his head. “If only I were so lucky-I’m afraid this cane is my only wife.”

I said to Rumely, “Seems like a decent sort.”

Rumely nodded. “By all accounts, he is. . That fellow there, with the black bushy beard, that’s Kessler.”

In a well-cut brown suit with darker brown bowler, the sturdy-looking, forty-ish Canadian wine merchant-known as the Champagne King-carried a brown valise so tightly his knuckles were white.

The reporters had questions for him, too.

“What sends you to Europe under this threat?”

“Business and pleasure,” Kessler said, a smile flashing through the black thatch that obscured much of his face.

“Which do you enjoy more, Mr. Kessler?” another journalist asked, good-naturedly. “Making money, or spending it?”

I knew from materials Rumely had provided me that Kessler loved to throw extravagant dinners and parties, particularly in Europe.

“That’s all part of the same process,” the bearded wine magnate said, with another grin.

“What’s in the bag, George?” a reporter asked, with impertinent familiarity.

The grin disappeared and Kessler said, “My clean underwear,” and turned away from the reporters, his good humor turned to irritation.

But the press boys didn’t seem to mind; Kessler was a minor celebrity compared to another man who’d just fallen into line.

In a wide-brimmed Stetson, an oversize blue velvet bow tie and a knee-length, loose-fitting duster-type tan overcoat, Elbert Hubbard (like Kessler) stood clutching a valise-a battered-looking leather one-waiting his turn next to his handsome wife, Alice, modestly attired in a blue linen one-piece travelling suit and straw hat. Hubbard was knocking on sixty’s door, and his wife was perhaps ten years younger. They both had brown, graying, shoulder-length hair.

The reporters were thrilled to see the eccentric homespun philosopher, and Rumely didn’t bother identifying the man to me, because Hubbard’s picture had been unavoidable in the press over the years, particularly after the success of his article “A Message to Garcia.”

“Fra Albertus!” one of the reporter’s cried, invoking a painfully precious nickname the so-called author had bestowed upon himself. As far as I was concerned, self-published books and magazines, and homely little stories and supposedly wry aphorisms, didn’t an author make.

“Yes, friend?” Hubbard said, smiling beatifically at the reporter, who was one of half a dozen swarming around him like flies near something a horse had dropped. “How may I help you?”

“Aren’t you afraid of the U-boat threat, Mr. Hubbard?”

“To be torpedoed,” he said, “would be a good advertisement for my pamphlet ‘The Man Who Lifted the Lid Off Hell.’ ”

“You mean the Kaiser, don’t you?”

“I do. William Hohenzollern himself. I intend to interview Kaiser Bill, you know.”

“You can’t interview him,” another reporter put in, rather snidely, “if the Lucy sinks.”

Hubbard lifted his shoulders in a theatrical shrug. “If they sink the ship, I’d drown and succeed in my ambition to get in the Hall of Fame. After all, there are only two respectable ways to die: one is of old age, the other is by accident.”

The reporters were writing down each glorious word. How I despised this middle-brow malarkey.

“I believe the drizzle has stopped,” Rumely said.

“Perhaps-but not the drivel.”

A brass band had begun to play, drowning out both Hubbard and the reporters; and even John Philip Sousa was a relief by way of contrast.

The reporters gathered around one last passenger, though with the band blaring, we couldn’t eavesdrop on the questions. I was probably too awestruck to have listened, in any event, because the passenger the reporters were clamoring around was a beautiful dark-haired, dark-eyed woman of perhaps forty, graceful, lithe, dignified, in a black dress with occasional white frills and a black bonnet with white feathers. Accompanying her was another tall, shapely woman, a little younger-in her mid-thirties, possibly-in a shirtwaist costume of tan cotton pongee with white linen collar and cuffs and, startlingly, no hat.

Rumely identified the beauty in black as Madame Marie DePage, the Special Envoy to the United States from Belgium. The wife of Antoine DePage, the Belgian Army’s Surgeon General, Madame DePage had spent several months in America raising money for her husband’s Red Cross-sponsored field hospital.

“She raised one hundred fifty thousand dollars,” Rumely reminded me.

“With that face, even I would have made a donation. . Who’s her friend?”

“No idea.”

Madame DePage’s female companion had high cheekbones and dark blonde hair and pale blue eyes-a striking combination of strength and femininity. She was almost as arresting as Madame DePage herself, and I found her even more fascinating-or was that just her anonymity?

All five of my prime subjects for interviews were standing in the distinguished line, the reporters having gone off trolling for other prey, when a Western Union delivery boy seemed to materialize, and move among them. The band covered up his questions, but he was clearly seeking the recipients of the wires.

Then all five-Vanderbilt, Frohman, Kessler, Hubbard and DePage-were curiously opening up the little envelopes, probably expecting a cheery bon voyage from a friend. . though I could not imagine the mutual friend that might have sent telegrams to these five. Of course, Western Union may have had missives from five separate senders and they were just delivered at the same time. .

And yet all of their reactions were the same! Frowns of disgust-even the sweet, positive-minded Sage of East Aurora, Elbert Hubbard himself, scowled. In fact, he wadded his telegram up, and hurled it to the cement.

No-wait. . I’d been wrong: Six telegrams had been delivered. Vanderbilt’s dark-haired slender friend had also received one, and he and Vanderbilt were shaking their heads, discussing what was obviously a mutually shared distaste for what they had just read. Only Hubbard, however, had discarded his telegram, the others folding theirs and sticking them away, into suit or pants pockets.

The line was moving forward now, and I shook hands with Rumely, and gathered my single suitcase, and got into the back of the queue. No one seemed to notice me pick up the wadded telegram Hubbard had discarded.

Nor did anyone seem to notice when I unfolded it like a crumpled flower to read: FRA HUBBARD-LUSITANIA TO BE TORPEDOED. CANCEL PASSAGE IMMEDIATELY IF YOU VALUE YOUR LIFE.

It was signed, rather melodramatically (and redundantly, I thought), MORTE.

THREE

A Self-Confident Fool

Off the coast of Scotland, the day before the Lusitania left port, one of the Kaiser’s submarines sent a British coal-carrying steamer to the ocean’s floor. In the Dardanelles, fierce fighting was afoot; and Britain and her allies were bombing German towns while warships attacked U-boat bases. And yet the passengers aboard the Lusitania — my innocent self included-seemed to feel immune from the conflict.

Even with the journalistic espionage I intended to carry out, I found myself lulled into peacetime complacency by the Big Lucy’s lavishness. Despite my criticism of its unlovely top-heavy exterior, I could only applaud the elegance of the ship’s internal beauty, from public rooms to accommodations; I had travelled numerous times on so-called luxury liners, but truly Cunard had set the standard with the Lusitania (and, presumably, with her sister, Mauretania).

This was obvious from the moment I boarded through the first-class entrance on the Main Deck. The entryway area-where a flock of ship’s crew (stewards overseen by a purser’s clerk) checked names off a list, dispensed room keys and gave directions-had a light, airy feel. The floor was tile, white with black diamond shapes, the furnishings white wicker, the woodwork a blazing white with golden touches, and scarlet brocade-upholstered settees were built into the walls. Potted ferns shared space with floral arrangements; there were so many flowers aboard the ship, the sweetness in the air was almost overpowering, like the visitation area of a funeral home whose current attraction was a popular fellow indeed.

As we all waited our turn with the stewards and purser’s clerk, the only annoyance was an overabundance of children, not all of whom were well-behaved, despite the best efforts of nannies; tiny shod feet echoed off the tile floor like gunfire, shrill little voices tearing the air. Oh well-this was to be expected. Cunard’s advertising bragged of the safety the Big Lucy provided mothers and children.*

“I wouldn’t worry, if I were you,” a rich alto voice almost whispered in my ear.

I looked to my left, where that tall hatless blonde female in the tan cotton pongee, Madame DePage’s friend, stood next to me. At the moment, her strong, handsome face tweaked itself with a smile, and her blue eyes had a twinkle; tendrils of her piled-high hair seemed to have a mocking life of their own. While no physical giant, I am certainly not a small man, and it was startling to look directly into the eyes of a woman on my own level.

“Pardon me?” I said.

“The kiddies,” she said, a corner of her mouth turned up, in sweet irony. “The ship provides numerous playrooms and nurseries. . In the days to come, you’ll be little troubled by having them underfoot.”

I could only return the smile. “Am I really that easily read?”

She gave me a tiny shrug. “Most people’s features are a map of their inner thoughts.”

“And I’m one of those?”

“Perhaps.”

I gave her half a bow. “S.S. Van Dine, madam. Who do I have the honor of providing me with this minor humiliation?”

She gave me her hand, and my fingertips touched hers. “Philomina Vance,” she said. “May I ask what the ‘S.S.’ stands for? You don’t look terribly like a steamship.”

“That at least is a relief. It’s, uh, Samuel.”

“Is that the first ‘S’ or the second?”

“Well, uh, it’s the, uh, first, of course. The other ‘S’ is quite unimportant.”

Another shrug. “Well, I’m going to call you Van.”

“You have my consent. And I will call you Miss Vance.”

“Anything but Philomina.” She flashed another smile, no irony at all now-but the eyes still twinkled. “You know, Van, I think we’re going to be great friends.”

“Really? And why is that?”

“Any man with the nerve to wear that Kaiser Bill beard in these times is either extremely foolish or enormously self-confident. And I like self-confidence.”

“But what if I prove a fool?”

“Oh, I like a good laugh, too. Either way, I should come out swimmingly.”

Then we reached the stewards, and went our separate ways. It took her rather longer to go through the rigmarole than I, because she seemed to be doing it for Madame DePage, as well as herself-though, strangely, the lovely and mysterious Madame DePage was nowhere to be seen.

Wearing their ornate grillwork doors like family crests, a pair of elevators-that is “lifts,” this was a British ship, after all-awaited to take Saloon passengers to Decks A and B, and their accommodations.* Since few people travelled alone on a transatlantic voyage, most of the cabins were designed for two or more occupants; but one of the handful of single cabins had been thoughtfully booked for me by my employer, Mr. Rumely. My cabin was on B Deck, on the portside of the ship, and the lift brought me to the deck’s entrance hall, where additional elegance awaited-white woodwork, Corinthian columns, black grillwork, wall-to-wall carpeting, damask sofas, more potted plants, further flowers. Offices opposite the lift curved around a funnel shaft.

Sun was filtering in through windows and down the stairwell, as I took a left off the lift past the wide companionway (as shipboard stairways insisted on being called) and then a right down the portside corridor, which bustled with other guests finding their bearings, often aided by bellboys in gold-braided beige uniforms. Moving past doors of various cabins on my right, and two expansive suites of rooms on my left, I found my cabin perhaps halfway down the corridor, at the juncture of a short hallway to my left, a single window at its dead end sending mote-floating sunlight my direction.

The cabin was on the corner of the corridor and the small hallway, and was a palatial cubbyhole without, unfortunately, a view onto the sea. What it did have was rather amazing, considering the limitations of space: a wrought-iron single bed, a washstand with hot and cold running water, off-white woodwork, electric lighting, a wardrobe and a bureau with mirror-better appointed, by far, than my Lexington Street apartment, and heaven compared to that boardinghouse room in the Bronx.

As there was no closet, I transferred the contents of my suitcase into the bureau drawers, and slid the empty bag under my bed. I was sitting on the bed, wondering when we’d be leaving port, when a gong clanged, making me jump-first of the “All Ashore” signals. I checked my pocket watch: half past eleven.

Even a man of sophistication can enjoy the simple pleasures of the spectacle of a great liner shoving off, so I made my way to the portside of the Boat Deck. In the corridor, the aftermath of good-bye parties coming to a close was evidenced by people hugging and kissing, those leaving expressing a wish to be going along, even as the “All Ashore” gongs continued to reverberate. The aroma of food being cooked announced in its unique way that the voyage was about to begin: The first meal was in preparation.

On deck, passengers were lining the rail, and I found a place for myself just beyond the first-class promenade with its hanging lifeboats, toward the bow of the ship-the area called the forecastle, from which the bridge could be made out easily. So could the sight of visitors streaming down the gangways; why did the image of rats abandoning a sinking ship pop into my mind? Far too trite a thought even to have.

Deckhands who had traded in their crisp white sport jackets for turtleneck sweaters and heavy, seaworthy windbreakers, performed a thousand small tasks beyond the average passenger’s comprehension; this whirl of activity, more than anything else, announced that the great ship was coming to life.

Cargo hatches were battened, and bells rang out as officers rushed up gangways with last-minute paperwork in hand, bills of lading and cargo consignments and such. The pilot’s H flag was hoisted from the halyard of the signal bridge, and on the narrow stern of the control bridge the American flag flapped, while upright streamers of myriad other flags ran up and down the fore and aft masts, lending a gay ambience worthy of a cruise ship. Less festive, even ominous, was the black smoke belching from the fat exclamation points of the black-painted funnels.

After the floral fragrance of the public areas of the Big Lucy, the deck presented olfactory reminders that this was, indeed, a ship. In addition to the coal smoke, engine oil and grease smells, and the pungent whiff of tarred decking and the nastily mysterious odors emanating from scuppers and bilges, the bouquet of salty sea air provided an ever-present reminder that this was-despite the Cunard line’s best efforts-a steamer, not a luxury hotel.

On the dockside sightseers and friends seeing off passengers threw confetti, and waved hats, hankies, miniature American flags and, when all else failed, their hands. I did not wave back: I didn’t know any of them, and Rumely had long since disappeared back into the reality of Manhattan.

“You really are a grouch,” an already familiar alto voice said, next to me.

I couldn’t suppress the smile as I turned to her, those loose tendrils flying like little blonde flags of her own in the breeze.

“Just because I don’t behave like a schoolboy,” I said, “waving at a bunch of strangers, doesn’t make me a grouch.”

“No. I am sure there are other factors.”

I laughed, once. “Miss Vance, are you following me?”

“Why, do you mind?”

“No,” I said forwardly. “The sooner a shipboard romance begins, the better, I always say.”

She arched a brow; her eyes were an impossible light blue, eyes you could gaze straight through to the core of her. . a core consumed, at the moment, with mocking me. “Is that what you think this is? The beginnings of a romance?”

I shrugged. “We only have a week. And, after all, you like my beard.”

She raised a finger. “No-I said I liked the self-confidence it indicated-that you’re a man who goes his own way. If I could have my way with you, I’d cut that beard off.”

“If I could have my way with you, I’d let you.”

She did not blush, but she did turn away so I would not see just how broad her smile was. And when she turned back to me, the smile had lessened but was very much still there. “You are a rogue, Mr. Van Dine.”

“I thought you were going to call me Van.”

“I should call you a horse’s S.S.”

And I laughed again-more than once. “I like you, Vance.”

“No ‘Miss’?”

“I don’t think so. Whether a shipboard romance develops or not, I believe you were right the first time.”

“How’s that?”

I half-bowed. “We are going to be great friends.”

Below, burly stevedores were hauling the creaking gangplanks onto the pier, really putting their elbow grease into it. Hawsers thick as a stevedore’s arm were cast loose from bollards, splashing into the slip’s scummy waters before the sailors drew the ropes up onto the decks.

Leaning on the rail, I asked her, “May I inquire what’s become of your companion, Madame DePage? I gather you’re travelling together.”

She nodded past me, looking up, and I followed her eyes to the bridge; on the deck beneath the row of windows, Captain Turner-all arrayed in his gold-braided finery, looking rather more distinguished in his commodore’s cap than he had in his bowler at Luchow’s-was holding court with five of his most distinguished first-class passengers.

Gathered about him in a semicircle were Miss Vance’s companion, Madame DePage, impresario Frohman, the “Champagne King” Kessler, and the richest man on any ship, Vanderbilt, as well as his lanky dark-haired friend, whose name I had not yet ascertained. The group consisted of every illustrious passenger who had received one of those mysterious telegrams-with the exception of the homespun Elbert Hubbard.

Miss Vance gave me a look that I understood at once to mean we should move closer, which we did, until we were near enough to overhear Turner’s remarks to his guests.

But it was Frohman who was speaking at the moment, the half-crippled producer leaning on his cane with seemingly all of his weight. “Tell me, Alfred-is it true you cancelled your passage on the Titanic the night before she sailed?”

The frog-like Broadway czar’s tone was genial enough, but the question had a certain edge.

Vanderbilt, with the face of a somewhat dissipated boy under that jaunty cap, said, “It’s true-I had a feeling about it.”

Kessler asked, “Any premonitions this time?”

The multimillionaire shrugged, and the crusty captain put a hand on Vanderbilt’s shoulder, and gestured down toward where Miss Vance and I stood. . but he was really invoking the swarm of passengers clustered along the rail. He said, in a blustering way (which was easier for Miss Vance and me to hear than the previous exchange), “Do you honestly think all these people would have booked passage on the Lusitania if they thought they could be caught by a German submarine?* Why, that’s the best joke I’ve heard all year, this talk of torpedoing!”

Captain Turner laughed, and so did Vanderbilt. I exchanged glances with Miss Vance-neither of us was smiling, much less laughing.

The same could be said for Madame DePage, who-in a musical voice touched with that accent shared by France and her native Belgium, so fetching in a woman, so obnoxious in a man-said, “I do not find this war a subject fit for the. . joking.”

The smiles vanished from the faces of Vanderbilt and Captain Turner, both men apologizing.

“I am concerned not for me myself,” Madame DePage said, her pretty dimpled chin lifted, “but for the wounded in this tragic atrocity.” The latter word, divided by her accent into four lilting syllables, had a poetry at odds with its meaning. “If this ship, she goes down, t’ousands will suffer in hospital.”

Madame DePage was referring to the $150,000 she had raised; this implied the cash was on board with her-a dangerous state of affairs even in peacetime.

“I have to say I share madame’s concern,” Vanderbilt’s slender friend said. “These warning telegrams are most alarming.”

I had thought that was the reason for this little gathering-for the captain to reassure his guests. But he was a ham-handed old salt, wretchedly awkward with people.

Still, he tried his best: “Mr. Williamson, I’m sure, when we trace them, these messages will be the work of some publicity hound. Please. . my friends. . think nothing of these things.”

The captain was gesturing with one of the telegrams.

Vanderbilt said, “I’m sure it’s just someone’s idea of humor. A tasteless joke.”

“Germany could concentrate her entire fleet of subs on this ship,” Turner blustered (this seemed a strange thing to say, by way of reassurance), “and we would elude them.”

“That’s quite a statement, Captain,” Frohman said.

“I have never heard of the sub that can make twenty-seven knots-and we can.”

“Flying that American flag will help,” said Vanderbilt’s friend, whose name apparently was Williamson.

Since America was not at war with Germany-and with the Lusitania repainted as she was-hiding behind the Stars and Stripes seemed a good way to deceive a U-boat commander. But it had been tried before, and the White House had complained to Cunard.

Turner did not respond to Williamson’s remark, and merely patted backs and gave out assurances that the warning telegrams were of no import, easing the group off the small raised deck with invitations to join him at his table for meals, if they liked.

“Someone was missing from that little gathering,” I said.

“I know,” Miss Vance said.

I arched an eyebrow at her. “Really? And who do you assume that person to be?”

Matter-of-factly, she replied, “Elbert Hubbard. He received one of those warning telegrams, as well.”

“Is that what they were referring to? Warnings they received?”

Miss Vance informed me coolly that Madame DePage had received a telegram warning her that the ship would be torpedoed-signed “Morte,” death.

I shrugged. “Perhaps the Sage of East Aurora didn’t receive a warning-perhaps a legitimate telegram came in to him at the same time these warnings arrived for the others.”

She shook her head. “I doubt that-not when he reacted to it in such disgust. He crumpled it and tossed it to the ground, you know.”

“Is that right? Well, again, perhaps its contents were displeasing to him without it having been one of these warnings. Perhaps someone wired Hubbard to inform him of what a complete nincompoop he is.”

She smiled a little. “I think he’s a great man.”

“You do not.”

“Well. . a good man. A well-intentioned man.”

“That’s something wholly other than ‘great.’ ”

Now she shrugged. “Well, I suppose we’ll never know what was in that telegram Mr. Hubbard received.”

“I suppose not.”

“Not unless you share it with me, Van.” She smiled at me, the eyes atwinkle again. “After all, you did pick it up.”

I would not like to know what my expression looked like: Surely my mouth was agape and my eyes were wide and I appeared more the fool than a self-confident man. I realized that my masculine charms had not inspired this fetching wench to seek out my friendship, after all-she had seen me pick up the discarded telegram, open and look at it, and had sought me out, in her wily surreptitious female manner. I was beginning to suspect she was a damn suffragette.

“Could I see it?” she asked sweetly.

“See what?” I asked, but my bantering was limp. I took the telegram from my suitcoat pocket and handed it to her.

“So Hubbard was warned, too,” she said, studying the crumpled paper.

“Why, are you a detective?”

Both eyebrows climbed her fine forehead and she asked innocently, “Do I look like a detective?”

“No. . but then, I don’t believe I look like a fool, yet apparently I am one. And here I thought you wanted to be my great good friend.”

“I do,” she said nicely, apparently genuine, as she handed back the telegram. “Van, I’m just a good friend of Madame DePage, accompanying her, looking out after her interests.”

A low hum began to emanate from deep within the ship, growing into a muffled roar; the ship’s four steam turbines began their rotation, and giant propeller blades made a muddy froth of the Hudson River.

I glanced at my pocket watch: twelve-thirty. All delays, all doubts, all fears be damned-we were finally pulling away, as the Big Lucy gave off three throaty blasts from her mighty bass horn.

“Shall we have lunch,” I asked, putting away my watch, “and discuss this further?”

But she was gone-Philomina Vance had disappeared into the crowd on deck.

And I stood there alone, strangely sad as the big ship-like a massive building pulling away from its foundations-groaned away from the dock. A brass band on deck was playing one song (“It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”), the band on the pier another (“God Be With You Till We Meet Again”), and somewhere a chorus was singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Shouts of farewell tried to climb over that cacophony only to be drowned out by the bellow of steam whistles.

Soon a trio of tugboats puffed up to the much larger vessel to nudge and cajole her bow, easing her around till she was pointing downstream. It didn’t take long for the faces on the dock to turn indistinguishable, and finally even the skyline of Manhattan was just a blur of brick.

“Would you like to have lunch with me?” that delightful alto intoned.

I turned toward the sound, hopefully, but tried not to show eagerness; she was again at my side, not a hint of guile in those clear blue eyes.

I said, “If you’re not a detective, you must be a magician.”

She smiled gloriously. “And why is that, Mr. Van Dine?”

“Because of these vanishing acts you pull off.”

She shrugged and offered me her arm. “You’ll just have to hold on to me, then.”

That sounded wonderful.

And I took her arm, like the fool I am, and went off for lunch with her, convinced no more ulterior motives lurked within that pretty blonde hatless head.

If I were a lesser writer, I would at this point say: little did I know. .

But of course, we all know I’m above such things.

FOUR

Warm Welcome

We took luncheon in the Verandah Cafe. Most passengers were availing themselves of the opportunity to get their first look at the ship’s fabled domed dining room; but Miss Vance said she preferred to save that treat for this evening. Though the day remained overcast, this shipboard outdoor cafe held a certain airy appeal for both of us, and the relative privacy was attractive, as well.

The cafe was on the Boat Deck, past a lounge area rife with rose-upholstered wall seats and chairs, and even a marble fireplace; the tones of white and gold continued to prevail. The cafe was at the after-end of the deck, a twenty-by-forty* area with a white ceiling and dark-wood pillars open to the first-class promenade. The floor was parquet, the furnishings a mix of wood and wicker, with little potted trees whose stick-thin trunks rose to bushy explosions of green.

We sat at a small round table whose white linen tablecloth was at odds with the casualness of the clientele, mostly men in caps with legs crossed, smoking cigarettes, reading newspapers. Miss Vance and I were the only mixed couple-and among the few patrons having luncheon.

I had a plate of dainty deviled-ham sandwiches with their crusts trimmed off-apparently here in first class, the upper crust preferred no competition; and Miss Vance partook of a cup of beef broth. We both had tea, although my lovely companion took hers iced.

“How is it that you became acquainted with Madame DePage,” I asked, with an offhandedness that I hope disguised my rapt interest. “If I may be so bold.”

“You may.” The breeze was doing wonderful things with those blonde tendrils. “The madame and I are not friends, although we are friendly. I’m a paid companion.”

“Ah. A secretary?”

She offered me half a smile, half a shrug. “Something along those lines.”

“Madame DePage must be a generous mistress.”

An eyebrow arched. “Why is that?”

I offered her a complete shrug, invoking both shoulders. “To book you Saloon passage.”

It was common practice for servants and others attending first-class passengers to have rooms in second class (though rarely in third).

“Actually,” she said, between sips of iced tea, “I’m sharing quarters with Madame DePage.”

“Is that right?”

“Yes it is. She has one of the Regal Suites.* The other, I understand, is Mr. Vanderbilt’s.”

I nibbled a corner off a sandwich. “My little cabin is just down the hall from one of the Regal Suites-is yours portside or starboard? On the left or right, that is.”

She smiled a little. “I know my portside from my starboard, sir-our suite is on your side of the ship.”

Perhaps that would prove convenient, I thought. But I was also struck by the way she had referred to the suite so possessively-“our suite”-which was somewhat less than a subservient attitude. . not that there seemed to be much in the way of subservience about Miss Vance.

“And how long have you been a writer, Van?” she asked casually.

I froze between bites and put down my sandwich. “I don’t recall mentioning that I was.”

“Aren’t you?”

“Truthfully. . yes.” I looked unhesitatingly into those remarkable eggshell-blue eyes. “I’m aboard on a journalistic assignment. In fact, you might be in a position to help me out.”

She cocked her head. “Really? How so?”

“I’m hoping to interview the travelling celebrities. . and your mistress, Madame DePage, certainly qualifies.”

With a tiny wave of a gesture, she said, “That shouldn’t prove difficult. The madame is friendly to the press-she has a point of view she’s most anxious to communicate. I would be happy to pave the way for an audience.”

I grinned at her-toasted her with my teacup. “Most generous of you, Vance.”

“My pleasure. . but I must say I’m a bit surprised you’re a reporter. I would have taken you for an author of fiction, or perhaps literary criticism.”

“Why not a poet?”

She was studying me the way a scientist looks at something smeared on a slide. “I don’t sense the romantic in you. . at least not in the conventional sense. You have an acid eye, of a sort that would seek expression more directly than in that elliptical way a poet might employ. . Besides, I don’t believe poetry would strike you as a manly pursuit.”

Miss Vance was remarkably insightful-although I had written some small amount of poetry, in my time-but I was wondering how she had gathered so much about me in so short a span.

“Vance,” I said, frankly exasperated and not a little impressed, “how did you arrive at the conclusion that I was any kind of writer?”

Her lips twitched with amusement. “Well, Van, you’re a very well-groomed gentleman-your beard is immaculately trimmed. .”

“Thank you.”

“But on your right hand, you have ink under your nails. . either from a pen and/or the messy ribbon of one of those beastly typewriting machines.”

Reflexively, I looked at the nails of my right hand and, to my dismay, she was quite right.

“In addition,” she said, “at the dock you were observing passengers in a manner that indicated you were either, one, an agent or police official, private or government; or, two, a writer intent on observing human behavior. In retrospect, I should have noticed that you were keen on only the celebrities standing in line, which would have sent me in the direction of journalism.”

This seemed quite a remarkable observation to me, and I said as much.

“Further,” she said, keeping right on with it, “your attire reflected money and a sense of style, and yet was brand-new-”

Now I had to interrupt. “Certainly it’s not unusual for a passenger about to board an ocean liner to dress in recently purchased apparel. What woman doesn’t buy a new ‘outfit’ for a trip?”

“Well, Van, you’re not a woman-”

“Thank you for noticing.”

“But your freshly purchased apparel, added to the other facts, spelled writer.”

“Why?”

“Writers, even the most successful of them, lead a relatively solitary existence, and most often work at home. It’s characteristic of the professional writer to be rather. . indifferent where fashion is concerned.”

Understanding, I said, “But a writer who’s attending a special event. . a play, an opera, a wedding. . will certainly go out and buy new apparel.”

Her smile indicated she liked that I was following her line of logic. “Yes. But this, added to these other seemingly insignificant details-topped off by your extraordinary gift with language-led me to risk sharing with you my assumption that you are, indeed, a writer.”

Maybe she was a detective, after all.

“Well, I am a writer,” I said, “and a damned good one, if you’ll forgive my frankness.”

“I like your frankness, Van. By the way, what’s your real name?”

Again, she had startled me.

“How. . why. .?”

She smiled and made a breezy gesture with her left hand. “The initials ‘S.S.’ for a man on a steamship voyage-could anything be more absurd? And when I asked you what the initials stood for, you had to think about it! You don’t strike me as a man whose limited mentality does not include a ready retention of his own name.”

I could only laugh; she had me!

But I told her, for reasons of my own, I needed to keep my real name to myself; she would have to be content with my pseudonym.

“I guess I don’t mind, terribly,” she said. “But perhaps I was wrong-perhaps you aren’t a writer.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. . mayhap you’re a German spy.”

I almost choked on my tea. “Please. . in time of war, that’s not amusing.”

Still, her expression was one of amusement. “Ah, but America is not at war.”

“Ah, but. . we’re not in America any longer. In fact, on this ship, we’re in Great Britain.”

She nodded. “An astute observation.”

A burly officer-in the typical white cap and navy gold-braided blazer-was swaggering down the promenade; he had broad shoulders, a shovel jaw and an amiable manner. I had never seen the fellow before, but he smiled and nodded at me, as if we were old friends. On the other hand, the officer was nodding and speaking to other passengers, who lined the rail, so maybe I was imagining things. .

“Do you know that gentleman?” Miss Vance whispered.

“No.”

“He seems to know you.”

And indeed the officer was striding over to us. I touched my napkin to my lips and stood.

“Mr. Van Dine?” the officer said, his voice a tenor, somewhat surprising coming out of such a formidable figure. He had dark bright blue eyes and rather bushy eyebrows, and was extending a sturdy hand.

Shaking it, I said, “I’m afraid you have me at a disadvantage, sir.”

He had a firm grip, but had stopped short of showing off about it.

“I’m sorry-you were pointed out to me, on deck,” he said. That struck me as odd: No one knew me to do that!

He was introducing himself: Staff Captain John Anderson.

And now I understood-this was the contact aboard ship Rumely had told me about, the Cunard employee aware of my real name, and that I was a journalist aboard to write flattering articles about the ship and its passengers.

I introduced Miss Vance.

“We’re honored to have Madame DePage with us,” Anderson said to her. He had the faintest cockney around the edges of an accent he’d obviously worked at to make acceptable to the upper-class passengers. “She’s a great lady, with a fine cause.”

“I’m so glad you feel that way,” Miss Vance said, not sounding terribly sincere.

“Would you sit down with us?” I asked him, politely.

Anderson seemed almost embarrassed, as he said, “I didn’t mean to interrupt, Mr. Van Dine. I’d hoped to catch you after lunch, so I might show you around a little.”

Miss Vance said, “We’re quite finished with lunch, Captain Anderson.”

“Well, I’m certainly free,” I said, “if you’d care to take time away from your duties to bother with me.”

“Not at all. I’m anxious to. . Miss Vance, would you care to accompany us?”

“You’re very kind,” she said, rising, “but I need to join Madame DePage. She likes to write her correspondence after lunch.”

“Can I escort you to her?” I asked.

“No. . I’m a big girl, gentlemen. I’ll find my way.”

And the individualistic Miss Vance nodded to us, and moved off down the promenade, or actually up-she was heading toward the entryway where an elevator or stairs could convey her to her employer.

“Interesting woman,” Anderson said.

“Fascinating.”

“Probably a suffragette,” he sighed.

“Probably,” I said. “But then, no one’s perfect.”

Anderson suggested we sit for a moment, and we did. He told me he hoped to help me arrange interviews, and offered to do whatever he could to make my access to the ship and its passengers as complete as possible, and my voyage a pleasurable one.

“We’re grateful to the News for this opportunity,” Anderson said, “to show potential passengers that this war scare is no reason to avoid travel.”

“Well, that’s a wonderful attitude, and quite the opportunity for a journalist. . And I’m happy that you seem willing to give me a sort of Cook’s tour, as I do want to write about the ship itself, and not limit my work to these celebrity interviews.”

Anderson’s smile was wide and infectious. “That’s good news, Mr. Van Dine. Shall we start?”

Of course, Anderson wouldn’t have been as cooperative if he knew I was here to search out contraband; so I worked hard to make a friend of him. It’s not a pretty thing, but money was involved-and, anyway, if the Cunard line was using passenger ships to transport war materials, the practice should be exposed. Passengers-like myself, about whom I cared greatly, after all-would be at risk, if this indeed were happening.

The tour I received was certainly complete, and the company entirely amiable-though I did not press Anderson with overtly prying questions, and neither did the good staff captain duck any of my queries. . even those of a more sensitive nature.

“What about these rumored guns supposedly hidden on deck somewhere?” I asked him, about midway in our tour.

“Like most rumors,” Anderson said, half a smile digging a hole in one cheek, “there’s a certain basis in fact. .”

I tried not to reveal the inner excitement I felt at this revelation.

“. . but the reality is rather less sinister, as I will demonstrate.”

At the appropriate moments during my tour, the staff captain pointed out to me four deck platforms-two forward, two aft-with mountings awaiting three- or six-inch guns. Either caliber would require dockside cranes, Anderson assured me, and such weapons could hardly be camouflaged, “much less hidden.”

This disappointed me, but I instinctively believed Anderson-his frankness seemed obvious, and his character appeared lacking in guile. (Nonetheless, in my spare time, I prowled every foot of deck space above the waterline; peering beneath any recess or overhang, checking under every winch, I saw no guns mounted or unmounted.)

Though Anderson’s affable candor impressed me, I did not yet feel comfortable enough with him to broach the subject of contraband-that, I felt, might come later. I would make it a priority to establish a friendship with the man, in hopes of learning more.

Anderson definitely was the man to whom I needed to get close: He admitted that “the internal distribution of the cargo” was very much his responsibility.

“And I do not take that responsibility lightly,” he assured me. “Faulty cargo planning can materially affect the trim of the ship, you know.”

“Indeed,” I commented, though truthfully I had not a clue.

Surely I could have asked for no more friendly nor knowledgeable tour guide. Anderson, anxious to impress the press with the Cunard line’s superiority, began with the fabulously luxurious public rooms of Saloon class, which might have been lifted bodily and set down on the ship out of some splendid hotel or exclusive London club. In addition to the description-defying dining room (about which more later), these included a reception room and various lounges, as well as music, reading-and-writing and smoking rooms. In addition, the ship offered a barbershop, a lending library, a photographer’s dark room, a clothes pressing service, a separate dining saloon for valets and maids, and even a switchboard for its innovative room-to-room telephone system.

I don’t consider myself easily impressed, but I felt as wide-eyed as a schoolgirl, strolling acres of deep carpet through first-class lounges extravagantly appointed with plush armchairs, marble fireplaces, grand pianos, rich drapes and expensive (if dull) oil paintings. A man of impeccable taste such as myself, marooned for months in cheap flats and ghastly garrets, could only wonder at this oasis of late-Georgian elegance, this world of silk waistcoats, gold watch chains, double-staffed settees, mahogany paneling, carved maple-topped tables and wrought-iron skylights.

Since I was travelling first class, Anderson did not bother showing me a sample of the sumptuous cabins. But I quickly became as impressed with the size of the ship as I had been with the luxury of Saloon class-the damned thing seemed to go on forever, interminable corridors with their polished linoleum floors and a dizzying profusion of white, red and blue lights marking exits, fire extinguishers, washrooms, pantries and other shipboard appurtenances, all within a maze of decks and companionways, towering masts and funnels and, of course, self-important people, some of them passengers, others stewards or crew members, the officers with their gold braids and medal ribbons seeming to wear perpetual expressions of faint disapproval.

Anderson was a pleasant exception to the latter, and I felt his genial nature was not due merely to my status as a member of the press. We passed between first, second and third class with no change in his attitude of friendliness toward passengers-a young man in ill-fitting clothing in steerage, seeking a new life in America, got the same nod and hello from Anderson as a Vanderbilt or Kessler.

Now and then, however, the staff captain would show a sterner side, if he encountered a crewman whose dress or bearing was not up to snuff. We paused for three or four of these dressing-downs.

Moving along from one of them, Anderson sighed and said, “It’s a problem, it is.”

“What’s that?”

He arched an eyebrow. “Off the record, sir?”

“Certainly. My goal here is to build up, not to tear down.”

“We are rather desperately understaffed,”* he admitted. “And some of the staff we have is, frankly, not up to snuff.”

“That doesn’t sound like Cunard’s style.”

“It isn’t. But the Royal Navy has scooped up many of our best crew, for the war effort. Finding able-bodied seamen for this trip was a chore, I must admit.”

“You don’t seem entirely satisfied with the result.”

“I’m not. There are crew members aboard who’ve never sailed other than as a passenger.”

This was the staff captain’s only negative remark of the tour, and I must say the meticulous craftsmanship of the ship’s construction carried over into the second and third classes. The public rooms of second class-from dining saloon to smoking room-could have been taken for those of the first class of almost any other ship sailing the North Atlantic. Plainer in style (white remained, gold did not), the public rooms were large and well-appointed; the example of a stateroom-a four-berth-that Anderson saw fit to show me was only a small step down from my own.