James White

Federation World

To Walter Willis whose example some forty years ago, and on many occasions since, made a young fan artist realize that words can say more than pictures

A Del Rey Book

Published by Ballantine Books

First Edition: June 1988

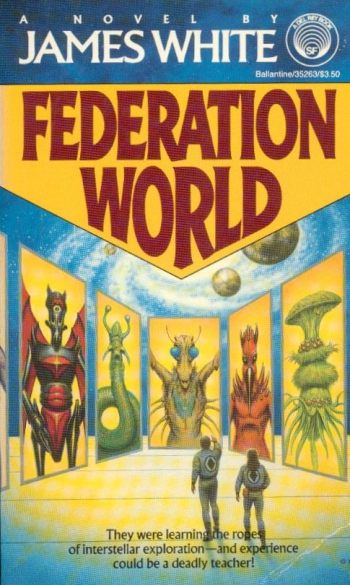

Cover Art by David B. Mattingly

Chapter 1

THE building was a white cube twenty stories high with a broad flight of white stairs leading up to the quietly impressive entrance on the second floor. From past experience Martin knew that the stairs retained their perfect whiteness no matter how many hundreds of people climbed them and that the sign above the entrance, which read FEDERATION OF GALACTIC SENTIENTS EXAMINATION AND INDUCTION CENTER, projected the same message regardless of the language or degree of literacy of the person viewing it.

He had not had the opportunity of speaking to a blind candidate for Galactic citizenship, but presumably he or she would have received the message in some other fashion.

As he began to climb, Martin saw that there were just three other people on the stairs-a young couple, working students judging by their age and dress, and an old man who was obviously much too frail to work. The oldster’s face had the anxious, stubborn look of one whose life on Earth had become untenable for a variety of reasons which forced him to try for something better, or at least different. The young couple climbed briskly and confidently, as if they knew what to expect at the top. Like Martin they had probably been here before and had had second thoughts. Unlike Martin they now seemed to have made up their minds.

Not wishing to get into a discussion with any of them, Martin held back to allow the others to precede him.

Going through that entrance was still a shock, he thought, and always would be no matter how often he did it. There was no physical sensation, just the shattering realization that one had arrived in the center of an enormous reception area with a transparent roof, and that it was not on the second floor but the twentieth. Like the perpetually white stairs and the omnilingual signs, instantaneous matter transmission was just another piece of technological intimidation aimed at making the backward Earth people more amenable.

The reception area was carpeted and furnished in warm, relaxing shades of gold and green and brown, and covered with random groupings of chairs and reading desks. All but a few of the chairs were empty, and the desks were heaped with Federation literature. Three of the distant walls were covered by large pictures, each of which showed a stylized, almost heraldic, representation of one of the member races of the Federation of Galactic Sentients. There were close to two hundred of the pictures ranged around the three walls and, so far as Martin could see, none of them was duplicated.

Along the wall facing him, like a row of unmanned reservation desks at an air terminal, were the examination computers.

By the time he reached them the old man had been passed through, and he could hear the young couple talking quietly to the visual display unit of the examiner. But they were several desks away and Martin could not tell whether they were asking or answering questions. Then suddenly they lifted their hands from the top surface of the unit and moved around the desk to disappear through one of the two doors beyond it, the door bearing the symbol which appeared on all of the Federation’s literature and equipment. He had been watching the successful candidates so closely that he walked into the outer edge of another desk.

The display unit lit up, and the words which appeared on it shone white against a field of deep green.

GOOD AFTERNOON, SIR. PLACE ONE HAND ON THE UPPER SURFACE OF THIS UNIT AND STATE YOUR REASONS FOR WISHING TO BECOME A CITIZEN OF THE FEDERATION OF GALACTIC SENTIENTS. PLEASE RELAX AND TAKE ALL THE TIME YOU REQUIRE.

Martin looked at the examiner, at the large, smooth cube whose only features were its display screen and the ever-present Federation symbol centered on top, and kept his hands by his sides.

He said, “I have studied the brochure and have asked questions not covered by it on two previous occasions. I do not want to waste your tune.”

THANK YOU. SIR. PLEASE PASS THROUGH ON THE RIGHT AND USE THE UNMARKED DOOR.

For a moment he thought about passing on the left and going through the other door, the one bearing the symbol of a black diamond with rounded sides set in a circle of silver, and which looked so much like a single, alien eye, then he discarded the idea. During his last visit he had tried to do just that and found himself without warning at the foot of the entrance steps, with prospective candidates looking anxiously at him in case they, like himself, might be expelled as temporarily or permanently Undesirable.

The induction centers had attracted a large number of Undesirables in the early days. There were stories told of individuals and groups who had tried to exert physical or psychological pressure of various kinds with a view to organizing private armies on the new planet. And there had been the more simple, direct types who had wished merely to dismantle, remove, and study the Federation equipment for its weapons potential. The response in all cases had been nonviolent, but salutary.

At the first sign of tinkering, either with the minds of the candidates or the induction center equipment, the offenders were moved-teleported-a distance of a few miles. The more persistent or aggressive ones found themselves suddenly on the other side of the planet, without their weapons, equipment, or clothing.

Martin considered himself at worst a borderline Undesirable, so he went through the unmarked door.

He found himself in a small room which, judging by the view from the window, was on a much lower level of the building. The room was bare except for the desk containing the examiner at its center, and the display screen was partially hidden by a female candidate standing before it. She turned her head briefly to look at him, then returned her attention to the screen.

She was tall, slim, dark-haired, with a firm and mature face and skin so smooth and unblemished that her age could have been anywhere between twenty-five and forty. Like the heavy, dark-rimmed spectacles she wore, her clothing was functional rather than decorative. Nevertheless, and in spite of what the examiner might decide about her as a candidate, Martin would not have described her as Undesirable.

“No, I am not frightened by your advanced technology,” she said quietly in answer to a question Martin could not see, “nor do I consider it to be magic. Your miracles are superscientific, not supernatural, in spite of the symbolism of the entrance stairs and the near Heaven you are offering us. But I keep wondering why you try so hard and often to impress us with this technology.”

Martin edged sideways until he had a clear view of the screen, upon which appeared,

IT IS OUR POLICY TO TAKE EVERY OPPORTUNITY TO DRIVE HOME THE FACT THAT THE ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY EXISTS. WHETHER OR NOT YOU HAVE OCCASION TO USE IT. OR HAVE IT USED AGAINST YOU IN THE FUTURE. DISTANCE WITHIN THE GALAXY MEANS NOTHING TO US. NEITHER ARE THERE ANY PROBLEMS OF TRANSPORTATION, SUPPLY. ACCOMMODATION. OR LIVING SPACE ON YOUR NEW HOME. WE ARE CAPABLE OF TRANSPORTING YOUR ENTIRE SPECIES. ALL OF ITS ARTIFACTS, DOMESTIC ANIMALS. LARGE NUMBERS OF NATURAL FAUNA, VEGETATION. AND EVEN THE ENTIRE GAS ENVELOPE OF YOUR PLANET WERE IT NOT SO POLLUTED AS TO BE SCARCELY BREATHABLE.

THAT TECHNOLOGY ENSURES THAT NO FEDERATION CITIZEN LACKS FOR ANYTHING IN THE PHYSICAL SENSE. WHAT THEY DO WITH THEIR MINDS IS THEIR OWN BUSINESS PROVIDED THE END RESULT OF THEIR THINKING DOES NOT INTERFERE WITH THE FREEDOM OF OTHER CITIZENS, EARTH-HUMAN OR OTHERWISE.

“I know, I’ve studied the brochure,” she replied sharply. “But I’m concerned about the long-term effects of such mollycoddling. Surely there is the danger that the whole race will vegetate, stagnate?”

YOU HAVE NOT STUDIED IT CLOSELY ENOUGH, OBVIOUSLY. THE INTENTION IS NOT TO FORCE YOU INTO IDLENESS BUT TO ENABLE YOU TO ACHIEVE YOUR FULL POTENTIAL. ALL INTELLIGENT SPECIES FEEL IMPELLED TO WORK AND BUILD AND THINK CONSTRUCTIVELY. HOBBYISTS, FOR EXAMPLE, FREQUENTLY DEVOTE MORE TIME AND EFFORT TO THE WORK WHICH INTERESTS THEM THAN TO THEIR SO-CALLED PROPER JOBS. BUT FEDERATION CITIZENS DO NOT WORK BECAUSE ANOTHER INDIVIDUAL TELLS THEM TO DO SO. NOR WILL THEY BE OVERPROTECTED. YOUR PEOPLE WILL STILL DIE BECAUSE OF OLD AGE, ACCIDENT, OR DISEASE. AND IF ANYTHING IS DONE TO CHECK THESE PROCESSES, IT WILL BE YOUR DOCTORS AND RESEARCHERS WHO DO IT. YOU MAY REQUEST FEDERATION ASSISTANCE WHENEVER YOU NEED IT, BUT THE REAL WORK WILL STILL BE DONE BY YOU.

IS IT STILL YOUR WISH TO BECOME A MEMBER OF THE FEDERATION?

“Y-Yes,” she said.

THERE IS HESITATION. HAVE YOU MORE QUESTIONS?

She nodded, then said, ‘Two, perhaps unimportant ones. You communicate with us pictorially or by projecting written language. Why do you use written rather than oral language? Also, it was twenty-two below zero and snowing heavily at my local induction center half an hour ago, and I left my protective clothing with the…”

THE QUESTIONS ARE UNIMPORTANT BUT THEY WILL BE ANSWERED. WE ARE CAPABLE OF PROVIDING AURAL TRANSLATIONS OF OUR COMMUNICATIONS. BUT THE TRANSLATION PROCESS ROBS THE WORDS OF MUCH OF THEIR EMOTIONAL CONTENT AND MAKES THEM SOUND, TO YOUR EARS, HARSH AND UNFEELING. THERE IS THE PROBABILITY THAT YOU WOULD BE LISTENING FOR EMOTIONAL TONES AND NUANCES. OR HIDDEN MEANINGS, WHICH MIGHT CONFUSE YOU AND DISTORT THE MESSAGE. VISUAL PRESENTATION OF THE WORDS REDUCES THIS PROBABILITY.

REGARDING YOUR PROTECTIVE CLOTHING. IF YOUR APPLICATION FOR CITIZENSHIP IS UNSUCCESSFUL YOU WILL BE RETURNED TO YOUR LOCAL INDUCTION CENTER. IF YOU ARE ACCEPTED FOR CITIZENSHIP YOU WILL NOT NEED THEM.

PASS THROUGH ON THE RIGHT AND USE THE UNMARKED DOOR.

Martin saw her shoulders droop with disappointment, but otherwise she remained motionless. She said, “What would happen if I were to be directed through the other door?”

ALL OF THE MARKED DOORS OPEN INTO THE FEDERATION WORLD WHICH WILL BE YOUR NEW HOME, SPECIFICALLY INTO ONE OF THE REORIENTATION CENTERS. THEY ARE THE DOORS USED BY SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES. THE UNMARKED DOORS ARE FOR THE NON-CITIZENS.

“Dammit, what’s the difference?”

NON-CITIZENS DO AS THEY ARE TOLD.

She opened her mouth to ask another question, but the examiner’s screen had gone dark. She looked at Martin, tried to smile and said, “Good luck.” The unmarked door closed behind her before he could reply.

QUESTIONS? The word appeared on the screen as soon as his palm made contact with the sensor plate.

The letters were white on bright red, he noted. The first examiner’s screen had been a restful shade of green and its conversation polite, even friendly, while the words he had seen projected onto this screen had been curt and downright critical at times. Perhaps the examiners were becoming impatient.

Martin wet his lips and thought, So non-Citizens do as they are told… This datum suggested that the Federation was something less than a perfect social organization since it contained lower grade or second-class citizens.

“The previous candidate asked some of the questions I had intended asking,” he said to give himself time to think and, he realized suddenly, because he was honestly curious. “Is it permitted to know her name and background?”

ONLY IF YOU ARE BOTH ACCEPTED AS CITIZENS OR NON-CITIZENS INTENDING TO WORK ON THE SAME PROJECTS. MY SENSOR INPUT SUGGESTS THAT THE QUESTION YOU WANT TO ASK IS NOT THE ONE BEING VERBALIZED. THIS IS A FORM OF DISHONESTY AND IS WASTEFUL OF EXAMINATION TIME. IF YOU REQUIRE MORE TIME FOR CONSIDERATION, YOU MAY RETURN LATER.

The green screen had told him to take all the time he needed, but this one was rushing things to say the least. Did the red screen imply a warning of some kind? Was he about to be failed?

POLITENESS AS WELL AS INDECISIVENESS IS ALSO A WASTE OF TIME. YOUR MANNER IS UNIMPORTANT. SPEAK HONESTLY. THE SENSOR PLATE IS NOT A TELEPATHIC DEVICE. BUT IT WILL REGISTER THE SLIGHTEST DEVIATION BETWEEN YOUR INTENTIONS AND YOUR WORDS.

IF YOU CANNOT ASK QUESTIONS, THEN VERBALIZE YOUR FEARS OR SUSPICIONS. AND REMEMBER THAT 1 CAN OFFER YOU NO VIOLENCE, SO DO NOT BE AFRAID. THE MOST I CAN DO IS DECLARE YOU UNSUITABLE FOR CITIZENSHIP

Martin felt himself begin to sweat. Why could he not simply accept everything he had been told and ask to be a Citizen? The standards for acceptance were unclear but, judging by the large numbers and types of individuals who made it, they could not be so high. Unless there was something inherent in his personality which rendered him unsuitable, something which was registering on the examiner’s sensor plate?

“Why do so many others qualify?” he asked suddenly. “Oldsters, children, people of average intelligence and below, or those with no particular skills or training? Some of them were accepted at first examination in less than fifteen minutes. I saw it myself.”‘

DO YOU CONSIDER YOURSELF SUPERIOR TO THEM?

He felt his hand sweating on the sensor plate and he thought, Be honest. Truthfully, he replied, “Superior to some of them. But why are they accepted?”

THEY ANSWER QUESTIONS. YOUR TYPE. INDIRECTLY OR OTHERWISE. ASK QUESTIONS. YOU ARE ABOUT TO ASK ANOTHER.

“Very well,” Martin said angrily. “Considering your advanced technology and its potential for giving virtually unlimited assistance, why must we leave Earth to join the Federation?”

THIS IS COVERED IN DETAIL ON PAGES 7 THROUGH 18 OF THE BROCHURE.

“I know, I know,” Martin said, wondering why a mere device, no matter how sophisticated its design, should make him feel like taking a sledgehammer to it. Was the examiner merely a terminal of an advanced computer as the brochure said it was, or was he taking their word for that, just as the unquestioning, unsuspicious, ordinary, and successful candidates for citizenship had taken it? More calmly, he went on, “I fully realize that our solar system is very far removed spatially from the center of galactic science and culture and that, because of your advanced transportation systems, this separation is more important psychologically than physically. But surely if we were to remain on Earth, our contacts with other Federation cultures would be more gradual, and natural?”

REFER TO PAGES 21 THROUGH 25.

Perhaps there was not a multi-tentacled Federation Citizen controlling the examiner as Martin had begun to suspect. It was behaving like a computer now, one which had been programmed by a bunch of extraterrestrial bureaucrats.

“I have studied those pages closely,” Martin said patiently. “Earth is a very sick planet. Polluted, overpopulated, and denuded of natural resources to such an extent that in a few decades starvation and war will result in virtual genocide, according to your people. You are probably right. But why, with the incredibly high level of technology which you are so fond of demonstrating to us, don’t you simply cure our sick planet? Forcing our people into premature contact with alien cultures could be dangerous.”

DOES THE PROSPECT OF MEETING EXTRATERRESTRIAL INTELLIGENCES FRIGHTEN YOU?

The sensor plate was clammy against his palm. Give an honest answer, he reminded himself, because if you do not, then this damn thing, whether it is a device or a front for a Citizen examiner, would be aware of it.

“I don’t know,” he said.

Chapter 2

THE screen remained blank, projecting an angry red rectangle on which he expected the words of rejection to appear. Not only was his palm on the sensor plate sweating, but he could feel sweat beading his forehead and trickling down from his armpits. And still the screen remained blank.

He continued staring into it, and, because those events were so much on his mind, he began to form mental images on the blank red surface of the arrival of the stupendous Federation ships…

They had made no secret of their arrival. Upward of two hundred mighty vessels, ranging in size from three hundred yards to three miles in diameter, had taken up positions in synchronous orbit above the equator to hang like a blazing necklace of diamonds in Earth’s night sky. Within the hour, they had identified themselves and given the reason for their presence.

The people of Earth were being given the opportunity of becoming Citizens of the Federation of Galactic Sentients. Examination and induction centers would be set up forthwith, and it was expected that the majority of the planet’s inhabitants would pass these examinations and move to a world which had no pollution, power, population, or food supply problems, where there were no deserts or arctic wastes, and where every square mile of the new world’s land surface was or could be made fruitful. To cushion the shock of first contact and to avoid the initial, and natural, feelings of xenophobia all communication between the Federation people and Earth candidates for citizenship would be by printed word only.

The invitation had appeared at hourly intervals on every TV screen in the world, and there was no way, short of switching off the set, of blocking the message. And when the big, white cubes which were the twenty-story induction centers appeared on pieces of empty ground convenient to the most populous areas, they could not be stopped either.

Many of Earth’s most powerful governments and their armed forces tried very hard to stop them, but neither political argument nor military force had any effect. Armored columns, massed artillery, tactical nukes, and various other forms of frightfulness were tried and just did not work-the conventional weaponry malfunctioned and the nukes were teleported far, far away to be sealed in vast, subterranean caverns beyond the possibility of recovery by the limited technology of those remaining on Earth who might try to use them.

It was pointed out very firmly that the invitation to join the Federation was open to all responsible members of the Earth-human race, but it did not apply to certain of the world’s political systems or any of its military organizations.

It was also pointed out that trust between the various species which made up the Federation was important, and that the earlier an Earth-human was able to trust the Galactic emissaries, the greater were his or her chances of being accepted as a Citizen. However, it was natural for a newly contacted race to feel suspicious of the Federation’s motives and worried about their own reactions to the new world. To reassure these people, two-way travel would be permitted between Earth and the new world for a limited period, by observers nominated by the Earth’s population, so that they could be satisfied in every respect regarding the desirability of the move from Earth. After this period, for administrative and logistic reasons, travel would be one-way.

Except for the very small proportion of Undesirables and non-Citizens who would remain, it was intended to complete the evacuation of Earth in ten years…

“What happens to the people who are left?” Martin asked suddenly. But the screen remained blank except for the imagined images which came like the pictures seen in the flames of an old-time fire.

Many millions of Earth-people had passed the examinations and moved to the new world on trust, sight unseen-although to be fair, most of them came from areas where subsistence level conditions left them with very little to lose. Then there were the people who worried in case these first Citizens were not capable of looking after themselves, and they wanted to go along to organize things for them. The would-be organizers had a much harder time satisfying the examiners regarding their suitability for citizenship. They had to make it clear, by word and past deeds and sensor plate readings, that they were the type of person who had the ability and the need to care for other people, and not just the kind who wanted power.

Despite the early influx of the more simple and trusting Earth-people, the Federation saw to it that nobody went hungry or unsheltered. But for psychological reasons it wanted the new Citizens to become self-supporting as soon as possible-too much help from Federation technology could, at this early stage, set up an inferiority complex which might stunt future cultural and scientific development. So the appropriate public buildings, educational establishments, dwellings ranging from mud huts to skyscraper blocks, and whole factory complexes, were transferee! with the minimum of physical and emotional dislocation.

One of the first and most pleasant discoveries made by the new arrivals was that the flora and fauna of Earth had been transplanted many centuries earlier and required only cultivation and domestication. Apart from the bright, stratospheric haze in the otherwise cloudless sky and the thirty-five hour day, the new world was very much like home. There was no moon, and the only way to see the sun was from a space observatory, but Earth’s space hardware was not on the list for transfer.

It seemed that the human race was not to be given interstellar travel, matter transmitters, or other technological marvels of Federation science, but they would be given a little guidance in discovering these things for themselves. There was plenty of time, after all, and no pressure of any kind would be exerted on them. The Federation was deeply concerned that the Earth culture should not suffer from forced growth.

Surely, Martin thought angrily, these were the actions of a sensitive, altruistic, highly ethical group of entities. Why could he not accept what they were offering at face value? What stupid defect in his personality was making him uneasy?

Martin wiped his palm with a handkerchief. The screen remained lighted but blank. He put the hand back again.

He remembered how the early reports and then the Earth observers had come back, the former in an increasing flood and the latter in a reluctant trickle. It was a beautiful world, its climate semitropical throughout because of the heat-retaining stratospheric haze, and the Earth vegetation and animal life were flourishing. In short, it was the kind of world his grandparents had insisted that Earth had been back in the good old days when there was room to breathe and air which was breathable.

But that had been nearly eight years ago, Martin thought as he stared into the blank red screen. The transfer of Earth’s population was virtually complete. Soon there would be nobody left but the people who, for personal or psychopathological reasons, were unsuitable for citizenship. There was nothing or nobody to hold him on Earth, and when he thought of the things he had heard and seen of the new world…

“I want to become a Citizen of the Federation,” he said in quiet desperation.

But he was all too aware of his palm on the sensor plate saying, not in words but in the electrochemical changes in his skin and the equally tiny variations in muscle tensions and pulse-rate, something different. Unlike his voice, those psychophysiological reactions were saying that all this was too good to be true, that there had to be a catch in it somewhere, and that there was something the minds behind the robot examiners were not telling him.

The words PASS THROUGH ON THE RIGHT AND USE THE UNMARKED DOOR appeared on the screen suddenly.

The door opened into a room in another building. Outside the window there was a vista of pine trees poking tike green spearheads through a blanket of sunlit, melting snow. He felt irritated because they still felt the need to impress him with their instantaneous transport system-had they never heard of the law of diminishing returns? But as he placed his hand on yet another sensor plate and looked beyond it his irritation changed abruptly to bitter disappointment.

Behind the examiner there was only one door, and it was unmarked.

QUESTIONS?

This time the word shone white on a field of icy blue, giving it an aura of cool, clinical detachment. But Martin did not feel anything at all like that.

“Am I being refused citizenship?” he asked angrily. “Am I an Undesirable? Am I wasting my time here?”

YOU ARE CURRENTLY A NON-CITIZEN. NOT AN UNDESIRABLE.

“What the blazes is the difference?”

THE STATUS OF NON-CITIZEN CAN BE A TEMPORARY CONDITION. UNDESIRABLES REMAIN SO.

Martin looked at the unmarked door again, remembering the girl candidate who had briefly shared an examiner with him before going… somewhere else. She had been told that the unmarked doors were for non-Citizens and that non-Citizens did as they were told. No matter what was decided in this room he would go through that door. There was no alternative, and suddenly he was frightened.

“I would like to return to my own locality,” he said as calmly as he could manage, “so that I can have more time to think.”

I STRONGLY ADVISE AGAINST IT.

He took his palm off the sensor plate and rubbed it against his thigh. He did not replace it.

YOUR CASE SHOULD BE DECIDED NOW.

The examiner, the room, and the view outside the window became very sharp and clear to him, as if he might be seeing them for the last time, and his mind was holding onto the present moment because very shortly something awful was going to happen. When he spoke his tone was too high-pitched and harsh, a stranger’s voice.

“What-what’s the hurry?”

NOTIFICATION OF PROCEDURAL CHANGE. UNTIL TOLD OTHERWISE YOU WILL ANSWER. NOT ASK. QUESTIONS. PLACE YOUR PALM ON THE SENSOR PLATE.

Martin swallowed and did as he was told. As soon as his hand touched the plate the questions began.

DO YOU WISH TO BECOME A CITIZEN OF THE FEDERATION OF GALACTIC SENTIENTS?

“Yes,” Martin said firmly.

SENSOR READING SUGGESTS RESERVATIONS, DO YOU WISH TO MOVE TO THE FEDERATION PLANET?

“Yes.”

YOUR ANSWER IS NOT FULLY SUPPORTED BY THE SENSOR. DO YOU NOT WISH TO LEAVE EARTH BECAUSE OF EXPECTED HOMESICKNESS, PATRIOTIC FEELINGS FOR YOUR BIRTHPLACE. OR OTHER EMOTIONAL REASONS?

“No!” Martin said vehemently. He was thinking of what the Earth had been even before the eight years of the Exodus had left it with little more than a skeleton crew of Undesirables and people tike himself who could not make up their minds or trust even themselves. Since his parents had died in a food riot twelve years ago, there had been nothing to hold him to any part of this sick and hopeless planet. He said again, “No.”

IS IT A MATTER OF TRUST?

“Yes.”

YOU ARE SUSPICIOUS OF OUR MOTIVES? DO YOU THINK WE ARE TELLING LIES?

“I’m-I’m not sure.”

BRIEFLY OUTLINE THE NATURE OF YOUR FEARS. SUSPICIONS. FEELINGS. OR GRIEVANCES REGARDING THE FEDERATION’S ACTIVITIES SINCE COMING TO YOUR PLANET.

Martin could not think of anything to say, but he knew that his palm on the sensor plate was saying far too much.

THE FOLLOWING IS A LIST OF THE MOST COMMON FEARS AND SUSPICIONS ENCOUNTERED DURING THE EXAMINATION OF CANDIDATES FOR CITIZENSHIP INDICATE VERBALLY THE ONE WHICH MOST CLOSELY APPROXIMATES YOUR CURRENT FEELINGS.

ONE: THE GALACTIC FEDERATION IS EVIL. INHERENTLY VICIOUS AND UTTERLY INIMICABLE TO MANKIND AND IS LULLING YOU INTO A FALSE SENSE OF SECURITY BY OFFERING THE EQUIVALENT OF HEAVEN ON THE NEW EARTH. WHERE YOUR RACE CAN BE EXTERMINATED PIECEMEAL WHILE BEING BEMUSED BY A COMPLEX AND TECHNOLOGY-SUPPORTED CONFIDENCE TRICK.

TWO: EARTH-PEOPLE ARE NOT DEMATERIALIZED AND TRANSPORTED TO THE NEW WORLD, THEY ARE RE MATERIALIZED WITHOUT PROTECTION IN SPACE WHERE THEY DIE.

THREE: THE EARTH-PEOPLE ARE USED SIMPLY AS FOOD FOR THE FRIGHTFUL AND INSATIABLY HUNGRY POPULATION OF THE FEDERATION.

FOUR: THE FEDERATION IS A FIGMENT OF THE IMAGINATION OF AN ALIEN RACE. SO VISUALLY HORRIFYING AND REPELLANT THAT IT COMMUNICATES THROUGH DEVICES LIKE THE EXAMINERS WHICH SUBTLY CONTROL THE MINDS OF THE CANDIDATES SO THAT THEY BELIEVE EVERYTHING THEY SEE AND HEAR.

FIVE: THE FEDERATION IS SO ADVANCED IN THE NONPHYSICAL SCIENCES THAT THE PICTURES AND OTHER EVIDENCE OF THE NEW WORLD, THE VAST FLEET OF SHIPS IN SYNCHRONOUS ORBIT, THE RADAR AND VISUAL IMAGES, AND THE REPORTS OF VISITORS TO THE NEW WORLD ARE THE RESULT OF DIRECT MENTAL CONTROL AND NONE OF IT HAS ANY PHYSICAL ACTUALITY.

SIX: YOUR PEOPLE ARE NOT BEING TRANSPORTED ANYWHERE BUT ARE DYING ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE DOORS MARKED WITH THE FEDERATION SYMBOL.

SEVEN: WE ARE SO COMPLETELY ALIEN AND INCOMPREHENSIBLE TO YOU THAT YOU COULD NOT EVEN CONCEIVE OF THE KIND OF PURPOSES FOR WHICH YOU WILL BE USED OR THE-

“But you understand us!” Martin broke in. “Surely understanding between intelligent races is a two-way process. That is a ridiculous suggestion.”

THE SENSOR REGISTERS AN OVERREACT10N TO FEELINGS OF DOUBT AND INFERIORITY. UNDERSTANDABLE. ARE THE OTHER SUGGESTIONS RIDICULOUS?

“Yes.”

BUT?

“Some of them are, well, worrying. The people who are being accepted for citizenship, while they are in many cases good, responsible, and sometimes highly intelligent people, are not the type who will make trouble if things aren’t what they expected. You’re taking away the sheep and…”

THE SHEPHERDS.

“… leaving the wolves on Earth. What right have you to do this to us?”

THE RIGHT OF A RESCUER TO SAVE A BEING INTENT ON COMMITTING SUICIDE. A BASIC QUESTION. DO YOU BELIEVE THAT WE MEAN YOU HARM?

“No.”

SENSOR INDICATES PARTIAL UNTRUTH.

“Not intentionally.”

EXPLAIN.

“You don’t intend to harm us,” Martin said firmly, “either as individuals or as a race. We would be hopelessly paranoid not to believe that you are trying to help us, even though your reasons for evacuating Earth seem a bit high-handed and, considering the resources available to you, not wholly convincing.

“As well,” he went on, “the brochure tells us that the Undesirables and non-Citizens who remain here will not suffer physical hardship unless they cause it themselves, but that the Earth will not be a pleasant place for them. On the other hand, the new planet will be a very pleasant place. So much so that there will be little for the Citizens to do for physical and mental exercise. They won’t even be able to run away from the wolves. In spite of the brochure’s reassurances, they may be opting for a cultural dead end, a world on which they will do as they like and risk degeneration and death as a species. Whereas on Earth you say that Undesirables and non-Citizens have to obey instructions. I wonder if they aren’t the lucky ones.”

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE IRRESPONSIBLE AND UNDESIRABLE ELEMENT ARE SIMPLE. THEY WILL NOT CAUSE PHYSICAL OR MENTAL HARM TO NON-CITIZENS REMAINING PERMANENTLY OR TEMPORARILY ON EARTH. THIS INSTRUCTION WILL BE ENFORCED NON-VIOLENTLY UNTIL THE POST-EXODUS SITUATION STABILIZES ITSELF. NON-CITIZENS, DEPENDING ON THEIR ABILITIES AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILES, WILL RECEIVE MORE COMPLEX INSTRUCTIONS. INSTRUCTIONS TO RESPONSIBLE NON-CITIZENS WILL NOT BE ENFORCED.

Earth would not be a pleasant place, Martin thought, but it would not be actively unpleasant if the responsible non-Citizens did as they were told. And the examiner seemed to be suggesting that they would do as they were told willingly because they would realize that it was for their own good. Whereas on the new world…

He said, “I can’t quite believe… Is there something you’re not telling me about the new planet?”

IS FEAR OF ULTIMATE BOREDOM THE PRINCIPAL REASON FOR YOUR INABILITY TO ACCEPT.THE NEW LIFE WE ARE OFFERING YOU?

“I–I suppose so.”

SENSOR CORROBORATES. CANDIDATE IS UNSUITABLE FOR CITIZENSHIP. PASS EITHER SIDE AND GO THROUGH THE DOOR FACING YOU.

Chapter 3

HE stumbled as he went through the door. There was a sudden feeling of vertigo, and he instinctively put out his arms to keep his balance. It was a small room for the number of people in it, and for a moment he wondered if he was in a descending elevator.

“You’ll gel used to it in a moment,” said the woman he had met earlier. Her face was pale, as if she had recently received some kind of shock, but her smile was reassuring and sympathetic. Apart from her there were six other people in the room, three women and three men of different ages and nationalities, and some of them smiled as well. They were all standing in front of the window, but they moved aside to let Martin see the view.

At first glance the stretch of harshly-lit, stony, and obviously airless ground made him think that he was on the moon-the low gravity would have explained his difficulty in keeping balance. But it was not the moon, he saw as soon as he raised his eyes above the horizon.

The sky blazed with stars-singly, in clusters, and in great, swirling, jeweled eddies-and so dense was the star field that it was difficult to find even a tiny part of the sky which was completely dark. Except, that was, in one area high overhead where there hung an enormous, black, featureless shape which looked at least twenty times larger than the disk of the full moon seen from Earth.

It was the shape of the Federation symbol.

Martin became aware slowly that his pulse was hammering loudly in his ears, and that he had been looking at the sky with such an intensity of wonder that he had forgotten to breathe. He took a ragged breath and said, “Is-is it some kind of black hole?”

NEGATIVE.

Because the room was tit only by that glorious starlight, he had not noticed the examiner until the word appeared white on a black screen. There was no sensor plate on top, and this examiner, Martin thought, was not fooling around with colored screens and subtle psychological pressures. He knew that his questions here would be answered simply and directly.

Unless they were forestalled…

THIS IS THE FEDERATION WORLD.

… or he began to see the answers for himself.

IT IS A HOLLOW BODY FABRICATED FROM MATERIAL WHICH COMPRISED THE PLANETS OF THIS AND MANY OTHER STAR SYSTEMS. IT CONTAINS THE INTELLIGENT BEINGS OF NEARLY TWO HUNDRED DIFFERENT SPECIES WHO ARE THE CITIZENS OF THE FEDERATION OF GALACTIC SENTIENTS. THIS WORLD, WHICH AMONG EARTH SCIENTISTS WOULD BE CALLED A MODIFIED DYSON SPHERE, ENCLOSES THE SYSTEM’S SUN AND USES ITS OUTPUT FOR LIGHT. HEAT. AND POWER FOR ITS SOIL SYNTHESIZERS, ATMOSPHERE PRODUCTION AND WEATHER CONTROL MACHINERY, GENERAL FABRICATION, AND FOOD SUPPLY

THE DIAMETER OF THE FEDERATION WORLD IS IN EXCESS OF TWO HUNDRED AND EIGHTY MILLION MILES AND IT HAS A USABLE SURFACE AREA, INCLUDING THE CONICAL EXTENSIONS AT THE POLES, OF NEARLY TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY QUADRILLION SQUARE MILES, OR WELL OVER ONE BILLION TIMES THE SURFACE AREA OF EARTH.

THE PROJECTED FUTURE POPULATIONS OF ALL THE PRESENT MEMBERS OF THE FEDERATION, TOGETHER WITH THOSE OF THE HUNDREDS OF AS YET UNDISCOVERED INTELLIGENT SPECIES WHO HAVE NOT YET BEEN INVITED TO JOIN. WILL NEVER BE ABLE TO FULLY POPULATE THIS WORLD.

The words, diagrams, and sharply detailed pictures flashed onto the screen, describing the Federation World, its topography, atmospheres, temperature and weather control machinery, and the light neutralizer fields which provided night and day for those species which needed them. It rotated ponderously and with seeming slowness, furnishing maximum gravity in the equatorial areas for those Citizens who had come from high-gee planets, and a diminishing artificial gravity approaching the poles where the surface was stepped and terraced so that the centrifugal force would be at right angles to the ground.

Citizens wishing to make contact with those of another species used ultralong-range aircraft or intra-plane-tary spaceships. Such contacts were encouraged, but only if they did not involve the risk of individual or species invasion of privacy. So touchy were some of the cultures that the stratosphere of the entire Federation World had been rendered opaque so that Citizens would not be able to watch each other through telescopes by looking upward and across their hollow superplanet.

The vast structure was a superthin eggshell of metal which was ultra-hard and fantastically dense, and the soils and atmospheres covering its inner surface were synthetic and produced when population additions required them. Where the atmospheres of adjoining species were mutually toxic, one-hundred-mile-high walls, transparent in the higher altitudes so as not to interfere with the sunlight, separated the two areas. These were similar to the walls which encircled the five-hundred-mile entry ports, positioned at the points of the conical polar extensions, to keep the atmosphere from being lost into extraplanetary space.

In the gravity-free polar areas were the great, thou-sand-mile-square tracts of bare metal on which were built the atmosphere and soil synthesizers, the matter transmitter units, searchship building and maintenance docks, and the power sources for the long-range projectors which could turn aside or destroy any astronomical body large enough to endanger the giant sphere by collision.

All at once the awful immensity of the Federation World, the incredibly high level of knowledge which had created and maintained it, and the inutterable pettiness of his suspicions made Martin want to run away and hide himself. He felt like an aboriginal grasshut dweller suddenly confronted with a block of skyscraper offices and Rush-hour traffic.

“You are inviting us to join you,” he said numbly, “and you built that!”

WE DID NOT BUILD THE FEDERATION WORLD; NOR WOULD WE BE CAPABLE OF DOING SO IN THE FORESEEABLE FUTURE. PLEASE TURN AROUND AND REGARD ME.

He turned quickly. The others, no doubt because they had already had this experience, turned more slowly. The wall on his right had become transparent, or maybe it was a wall-sized television screen showing a creature, lying or perhaps standing surrounded by a complex control desk. It was vaguely crablike, with too many legs; and appendages; the body was covered by warty excrescences and fleshy, frondlike growths. The single eye was wide and bulging, like a transparent sausage with two independently moving pupils. He had seen a pictoral representation of one of these beings in the reception area of the induction center, but this entity bore about as much resemblance to the picture as a real animal did to a cute cartoon treatment by Disney.

NO DOUBT YOU FIND ME AS VISUALLY REPULSIVE — AS I DO YOU. THE FEELING DIMINISHES AFTER REPEATED CONTACT BUT TO ANSWER THE QUESTION YOU WERE ABOUT TO ASK. THE FED-WORLD WAS THE ULTIMATE PROJECT, IN PURELY PHYSICAL TERMS, OF AN INCREDIBLY ANCIENT RACE WHICH NO LONGER DWELLS ALTHOUGH THEY STILL MAKE NON-PHYSICAL CONTACT EVERY FEW CENTURIES IN WE NEED ASSISTANCE OR ADVICE. THE PROBABILITY IS THAT THEY HAVE EVOLVED TO A STAGE WHERE PHYSICAL EXISTENCE IS NO LONGER A REQUIREMENT. THEY ARE THE BUILDERS.

MY RACE, WHICH WAS THEN AND STILL REMAINS THE MOST HIGHLY ADVANCED OF THOSE ENCOUNTERED IN THE GALAXY, WAS AMONG THE FIRST TO BE INVITED TO JOIN THE FEDERATION WORLD. WE ALSO HAD OUR SHARE OF RESTLESS AND IMPATIENT ENTITIES WHO WERE NOT SURE THAT THE SAFE. PROTECTED, AND INFINITELY SPACIOUS FEDERATION WORLD WAS FOR THEM. THESE PEOPLE WERE SELECTED AND TRAINED BY THE BUILDERS TO DO THE RELATIVELY MENIAL TASKS. ON EARTH YOU WOULD CALL US ERRAND BOYS, ODD-JOB MEN, SERVANTS. WE WERE TAUGHT HOW TO USE AND MAINTAIN THIS WORLD’S EQUIPMENT. OTHER SPECIES COMMUNICATION AND ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUES, AND THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF HYPERSHIPS FOR THE CONTINUING SEARCH PROGRAM.

WE FOUND THAT IN EVERY SPECIES SO FAR INVITED TO JOIN THE FEDERATION THERE WERE INVARIABLY A SMALL NUMBER WHO, INTELLECTUALLY OR EMOTIONALLY. COULD NOT ACCEPT THE INVITATION. THESE ENTITIES, THE NON-CITIZENS. CONTINUE TO JOIN US AND ASSIST IN PERFORMING THE TASKS SET BY THE BUILDERS.

One of the being’s appendages rose ponderously to indicate the dense, shining star field and the pointed, ovoid silhouette that was the great, single world of the Federation of Galactic Sentients, and it went on,

OUR PRINCIPAL TASK IS TO SEEK OUT THE INTELLIGENT RACES OF THE GALAXY AND BRING THEM INTO THE SECURITY AND FREEDOM OF THE WORLD THAT THE BUILDERS HAVE PROVIDED FOR THEM, BEFORE THEY PERISH IN THEIR OWN PLANETARY EFFLUVIA OR SOME OTHER CATASTROPHE BEFALLS THEM.

AFTER SUITABLE TRAINING, YOUR TASKS WILL INCLUDE ASSISTING US WITH SEARCHSHIP OPERATIONS AND CANDIDATE ASSESSMENT, WORK WHICH, CONSIDERING YOUR PRESENT STAGE OF DEVELOPMENT, WILL TAX YOUR ABILITIES TO THE FULL. TO AID YOU THERE ARE THE FACILITIES OF THE FEDERATION MEDICAL ESTABLISHMENTS WHICH WILL EXTEND YOUR LIFE SPAN AND PHYSICAL CAPABILITIES SO THAT YOUR LENGTHY TRAINING CAN BE PUT TO EFFECTIVE USE. IF AT ANY TIME YOUR WORK AS A NON-CITIZEN BECOMES TOO ONEROUS. YOU WILL BE GRANTED FEDERATION CITIZENSHIP AS A RIGHT.

LIFE IN THE FEDERATION WORLD IS MORE LEISURELY. ITS PURPOSE WAS AND IS TO BRING TOGETHER ALL THE INTELLIGENT RACES OF THE GALAXY AND LET THEM INTERMINGLE AND GROW SO THAT, IN THE FAR FUTURE, THE PURPOSE OF THE BUILDERS WILL COME TO FRUITION. THIS PURPOSE IS PRESENTLY INCOMPREHENSIBLE TO US, BUT WE HAVE BEEN TOLD THAT THE COMBINED INTELLIGENCE AND POTENTIAL OF THESE FUTURE FEDERATION CITIZENS WILL FAR SURPASS ANYTHING ACHIEVABLE BY EVEN THE BUILDERS. IT WILL BE A SLOW, NATURAL PROCESS, HOWEVER, KEPT FREE OF ANY KIND OF FORCE OR COERCION.

IN THE MEANTIME WE SHALL BE BUSY SEEKING OUT AND ADDING RACES TO THE FEDERATION, ENSURING ITS SAFETY FROM NATURAL THREATS FROM WITHOUT AND THE POISON OF UNDESIRABLES FROM WITHIN. YOUR LIFE FROM NOW ON WILL BE VERY BUSY, PERHAPS EXACTING. BUT NOT LONELY AS THE SERVANTS AND PROTECTORS OF THE FEDERATION, YOU WILL.COOPERATE CLOSELY WITH AND LEARN TO UNDERSTAND ENTITIES OF MANY DIFFERENT SPECIES. LONG BEFORE THE CITIZENS ARE READY TO DO SO. BECAUSE WE HAVE A VERY IMPORTANT QUALITY IN COMMON — THE QUALITY WHICH OUR SYSTEM OF EXAMINERS WAS PRIMARILY DESIGNED TO UNCOVER.

For a few moments the screen remained blank, and ‘ Martin looked quickly at the other people in the room. The woman he had met earlier smiled faintly and said, “They do say that it is better to start a job at the bottom…” The others seemed to be looking somewhere deep within themselves and were silent.

He returned his attention to the monstrous, crablike being. Was it his imagination or was there really a glint of amusement in that great, bulging sausage of an eye as once more the non-Citizen’s words were projected onto the screen.

CONGRATULATIONS. YOU HAVE BEEN EXAMINED AND HAVE BEEN FOUND UNSUITABLE FOR CITIZENSHIP IN THE FEDERATION OF GALACTIC SENTIENTS. PREPARE YOURSELVES FOR IMMEDIATE TRANSFER TO THE EARTH-HUMAN PRELIMINARY TRAINING SCHOOL ON FOMALHAUT THREE.

Chapter 4

BY the time they had reached the final stages of their training on Fomalhaut Three they were eleven Earth-years older and, thanks to the advanced medical science available, they looked and felt at least that much younger. Several times Martin had asked by how much their life spans had been extended, but that was one of the questions which their supervisor refused to answer, saying that if they did not complete their training to its satisfaction they were likely to end their lives prematurely in some stupid and avoidable accident, so that giving them information regarding their probable life expectancies would serve no useful purpose.

They were now in possession of the knowledge and ability to control and direct mechanisms of a complexity and power undreamed of by the people they had been on Earth-although they had still, their superior insisted, to acquire the experience and wisdom to use this power effectively. So they had waited and trained to an even finer pitch, wondering when, if ever, their first assignment would come.

Due to training commitments, their original classmates and one-time friends had gradually drawn away from them to disappear, two by two, in the directions of their chosen specialties. But there were compensations. As the training programs of Martin and Beth, the woman he had seen during that final visit to the examination and induction center back on Earth, began increasingly to overlap, and their friends to move away, Beth and he had drawn-or had they been forced? — closer.

It was a disturbing thought, particularly when, as now, it returned to trouble both of them at the same time. Martin slipped his arm around Beth’s shoulders and drew her back into the relaxer which, as well as being sinfully soft, was set for one-quarter gee. But her arm and neck muscles were stiff with tension, and she was wearing her totally unnecessary spectacles, which was not a good sign.

“How much does that slimy, supercilious supervisor know about us?” she asked, so softly that she might have been speaking to herself. “Was a few hours with the interrogation robots at the induction center enough to tell it everything! And if it knows everything, how accurately can it predict our behavior? Have we any free will, any choices? More importantly, have you, had you, any choice at all?”

“We can always choose to fail the next test,” Martin said, in an attempt to change the subject. “But it might well be that, in our situation, teacher knows best.”

“It knows us well enough to know that we wouldn’t deliberately fail a test,” Beth said impatiently. “And you know what I mean. We had no choice, no competition, no chance to make comparisons. I know that you were, well, impressed by Kathy. She impressed hell out of all the men, she’s gorgeous, dammit. If things had been different you might have preferred…”

Looking miserable, she left the sentence hanging.

Martin gave her shoulders another sympathetic squeeze, trying to draw her closer. But the warm, yielding, and normally responsive body had become that of a cold, fleshy mannequin with tension-frozen joints. He sighed, remembering that during their first meeting in the induction center so long ago, before he had even learned her name, he had decided that she was a lovely and highly intelligent young woman who took things much too seriously.

He had found no reason to change his mind about her when they met in the spacious living module occupied by the school’s Earth-humans, or during recreation periods in the forests and lakes overlying that tremendous underground training complex. Fomalhaut Three provided an environment suited to the needs of many of the Galaxy’s warm-blooded, oxygen-breathing races, and much of its training and large-scale simulation equipment was hi common use. But none of the trainees, including Martin, were allowed to make contact with a member of another species until they had graduated from the school.

He and Beth had met more and more frequently as their chosen specialties required them to share training simulations of increasing complexity, duration, and degrees of risk. She, who once had been responsible for the computer control of traffic in a small Earth city, and who was now able to direct energies and engines capable of changing the topography of a continent; and he, a cynical, discontented, one-time lecturer in zoology who, it seemed, was destined to do little else but talk. He shook his head and brought his mind back to the present time and problem.

“You’re forgetting,” he said quietly, “that the only one of us to impress Kathy was George. George with the muscles, and mustache, and the teeth. Did you fancy…”

“No,” she said firmly. “Kathy is welcome to him.”

“Besides,” he went on, “they’re both specializing in multi-environmental plant and animal husbandry. Fine, demanding, vitally important work, no doubt, especially if they want to stay inside the World, but it is still only fanning. Teaming up with a ship handler, the class’s only trainee hypership captain, no less, is much more fun. For personal as well as professional reasons.”

Beth did not smile as she turned her head to look at him, and her eyes were hidden by light reflection in her spectacles.

He went on. “It is quite possible that the supervisor knows our minds much better than we do, and that would include being able to predict what we are likely to do in any given situation. But what of it? That creature is hyperintelligent, not omniscient, and I think that its thought processes are just too alien for it to be able to influence us against our wills where anything so subtle as Earth-human emotional relationships are concerned. The decisions we made, and will make, are still our own, regardless of the fact that it probably knows about them in advance. The point I’m trying to make is that, had the supervisor given you more female competition by confronting me with a dozen, or a hundred, tall, dark-eyed, lovely women who know what I’m thinking almost before I do, the process would have taken much longer, and wasted a lot of our supervisor’s precious training time, but ultimately I would have made the same choice.”

He felt her relax, but not completely, as she allowed herself to settle into the backrest beside him.

“If I had been confronted with a hundred men..” she began.

“I was lucky you weren’t,” he said.

Irritably, she said, “How can I argue with you when you always say the right thing? But I keep forgetting that you’re training as one of those devious-minded, smooth-talking specialists in First Contact who never stops practicing…”

“This,” he reminded her gently, “is not the first contact.”

There was a small movement of her shoulder, and he felt her hand creep gently into his and grip the fingers tightly, and he knew that she, too, was remembering that first contact and all the tension and terror of the protracted, technological nightmare that had preceded it.

It had happened during one of their early shared training exercises, when they were still trying to familiarize themselves with what the supervisor, a being renowned for the magnitude of its understatements, referred to as the basic tools of the trade.

The tools of their trade…

Tool One, the hypership: the largest general-purpose vessel operated by the Galactics; just under half a mile in length, one-third that at its widest point, bristling with such an angular, metallic outgrowth of hyper-drive generator assemblies, normal-space drivers, tractor and pressor beam projectors, weather control machinery, and long- and short-range sensors that it was incapable of making anything but the most catastrophic of crash landings on a planetary surface. Internally it was packed with enough power generation equipment to satisfy the demands of one of the Galactic’s most energy-hungry cities, as well as a small army of monitor and self-repair robots, fabrication modules capable of producing anything from a pair of boots to a medium-sized interplanetary space vessel, synthesizers for the crew’s organic consumables, and, in executive charge of ail these systems, a computer which, to describe it as superhuman would have been to damn it with faint praise indeed. In spite of its virtual omniscience, the main computer was subservient to the wishes of its organic crew, although not always without argument.

This was one of the Galactics’ standard-issue tools, varying from ship to ship only in the control interfaces, living quarters, medical support, and food and translation systems required by its organic occupants at the time.

Tool Two, the lander: a small, fast, low-level reconnaissance vessel and surface lander, with crew positions for two but capable of being controlled remotely by the mother ship. Designed as a secure base for the First Contact specialist, it carried the full spectrum of communications equipment and, in the event of the contact going sour, its meteorite screen was also capable of protecting the occupant from ground or air attack by anything short of nuclear weapons.

Tool Three, the protector: a small, surface observation vehicle capable of operating within the most hostile of environments while enabling its crew to communicate with any intelligent inhabitants who might be present. For defense it relied principally on high mobility, but in the event of it encountering a threat from which it could not run away and which threatened the life of an organic occupant, it had power sufficient for a short-range matter transmission link with either the lander or the hyper-ship.

The other tools were much smaller, more specialized, and tailored to the needs of the Earth-human life-form. These included mobile, self-powered protective envelopes, proof against any hostile environment they were likely to encounter; a variety of nonlethal or psychological weaponry; and a two-way translator terminal so small that it could be disguised as a piece of ear or neck jewelry, and possessing a silent voice-bypass facility which enabled the contacter to hold simultaneous conversation with the mother ship without the risk of giving offense to an alien contactee.

But in that first major test, given without prior warning during the start of an otherwise routine training exercise to power-up a cold lander, the majority of those increasingly familiar tools were deliberately withdrawn from use.

It was a simulated, near-catastrophic malfunction which had opened the hypership to space and taken out the on-board power generation and all of the systems controlled by the main computer. They protested, reminding the supervisor that they had been taught that the hypership’s design philosophy made such an event impossible. But they were told that it was a simulated and not a real event, that it was designed to test, under conditions of extreme stress, their suitability for their chosen specialties, and that if they put into practice everything they had been taught up until that time, they should be able to survive the test without serious damage or life termination.

Within seconds of the first malfunction alarm, the lander’s hull sensors reacted automatically to the loss of external pressure and simulated radiation build-up by sealing all entry and inspection ports, effectively trapping them in a ship within a ship.

Considering then- level of technological ignorance at the time, it was obvious that they could not do anything about the condition of the distressed hypership, so that the most that was expected of them was to act as they would have done had the situation been real, and call for help.

But the distress beacon was mounted outside the hypership’s hull, and they were trapped inside a lander whose power cells and consumables were all but depleted. A hurried inventory showed that they had enough energy to maintain an air supply for two people of thirty-six hours, provided they remained at rest and did not use the available power for light, heat, artificial gravity, or communication with anyone or anything outside the lander.

Plainly they had to breathe less, but communication was vital.

The main computer was down, and with it all of the mother ship’s remote control systems. Through the crackle of simulated radiation interference, Beth was able to make intermittent contact with the three, self-powered repair robots assigned to the lander dock area. The robots were capable of performing a variety of delicate, precise, and quite complex tasks, she told Martin, provided they were given equally precise and complex instructions. Being in-organic and capable of operating in an airless, radioactive environment, it was possible for them to be given directions for finding and operating the manual release for the distress beacon-if she could remember the complicated internal geography of the mother ship and none of the different paths she programmed them to follow were blocked by simulated wreckage. But the first two robots died on her long before reaching their objective.

Beth complained angrily that the stupid things had done what they were told, not what she wanted them to do, and began the even more precise and careful instruction of the third and last one.

While she was working, Martin opened the seal between the flight deck and lock chamber to allow maximum circulation of their remaining air. Then he detached the wide, one-piece padding from their control couches and tied the attachment straps together to form a makeshift sleeping bag which he anchored loosely beside the direct vision port. Since the heating had been turned off, it was becoming colder by the minute-doubtless the rate of heat dissipation into space was being accelerated for the purposes of the test. He checked the food storage locker again, finding only two water bulbs and the characteristic shape of a self-warming food container, but the glow coming from their only working communicator screen was too dim to let him read the label.

Martin had succeeded in detaching one of the cabinet’s short, metal shelves when the communicator began producing louder and more regular hissing sounds overlaying the background interference-the distress beacon was functioning. A few minutes later the communicator screen went dark as Beth directed what little power remained to air production.

Hastily they shared the hot food and fumbled their way into the makeshift sleeping bag. Then they put their arms around each other, the first time they had done so, and breathed slowly and economically and remained otherwise motionless. There was nothing they could do but try to conserve the remaining air, pool their body heat, and await rescue.

They had no way of knowing how long that would take, or if it would come in time. Their supervisor would not deliberately let them die, they thought, but it was a completely alien lifeform with a metabolism utterly unlike their own, and a misjudgment might occur.

It was also possible that then’ rescuers had arrived, and were trying vainly to raise them on the dead communicator before beginning a long, time-wasting search of the entire hypership. That was why Martin, at what he thought were reasonable intervals, reached outside their cocoon of relative warmth to hammer his piece of shelving against the nearest bulkhead, to signal their presence and position to rescuers who were probably not there yet.

A subjective eternity passed as they drifted weightless in the utter darkness, staring out of an unseen viewport at an equally dark lander dock. The temperature continued to fall, the air-maker’s status light had dimmed to extinction, the air was thick and stale and painfully cold in the lungs. The sweat on Martin’s face felt like a film of ice and there was a pounding ache in his head that seemed louder than the noise he was making with the shelf. Through their thin coveralls he was aware of every curve and contour and movement of Beth’s body, which had begun to shake with a motion that was slower but more violent than shivering. It was the uncontrollable tremor of fear.

“If you’re as cold as all that,” he whispered between deep, unsatisfying gulps of stale air, “I’ve just thought of a nice way of generating more body heat…”

“L-liar,” she said through chattering teeth. “I’ve felt you thinking it since we got into this bloody, two-person straight-jacket. No. A-apart from.. from other considerations, dammit, it would be too wasteful of energy and oxygen, and it would let in the cold.”

She was still shaking, and holding him more tightly than before.

“Don’t worry,” he whispered reassuringly. “It’s only a matter of time before we’re rescued. And I’d say you passed this test, no doubt about that. The way you directed that last repair robot to the beacon, with the ship hi darkness and relying on memory alone for internal navigation, that was really fine work.

“As for me,” he went on, taking another deep, gasping breath, “I’ve done nothing at all but talk and make noise. If you want to worry about something, worry about me flunking this test.”

She had stopped trembling, and now it was her turn to be reassuring. He felt her cold, damp forehead rest against his equally clammy cheek as she said, “Moral support is important at a time tike this. It’s the only kind that doesn’t waste energy. Besides, the sleeping bag idea was yours. I would have put us into the unpowered space suits, where we would have frozen to death by — Look!”

Bright, greenish-yellow light was streaming through the direct vision port and reflecting from the dead screens and control console. It was coming from a large vehicle with the unmistakable outlines of a manned rescue pod which was drifting through the unlit dock and toward their Under. But as it moved closer, and he heard it dock with their entry port, he saw that some of the structural details were unfamiliar. Frantically he began battering at the viewport surround with his length of shelving.

“Take it easy, they know we’re here,” Beth said, grabbing his arm. “What’s the matter with you?”

“That isn’t the rescue pod we trained on,” he said urgently. “The configuration is slightly different. And look at that, that yellow fog inside the canopy, and their interior lighting. Dammit, our simulated bloody rescuers aren’t even human! I’ve got to make them understand that we belong to a different species, and work out a way of telling them so before they open our lock and poison us with their air. Let go of my arm!”

“Hammering won’t tell them anything,” Beth said. ‘They’ll think we’re naturally excited at being rescued. But-but I’m sure you’ll think of something.”

Neither of them mentioned the fact that he was supposed to be the specialist in other-species communication, that the problem was all his, and that it was now his turn to be tested. Beth’s face looked white even in that yellow light, and frightened, but the concern in her eyes seemed to be only for him.

He had to communicate urgently, send detailed physiological and metabolic data to an alien and intelligent lifeform, from a dead ship whose only channel of communication was a piece of metal shelving.

Or was that the only channel?…

“Close the bag after me and stay inside,” he told Beth, and wriggled out into the biting, breath-stopping cold.

He was already searching the control deck with his eyes, but his head was enveloped in clouds of condensation, and objects in the weightless condition had the habit of drifting into dark corners. He wasted several precious minutes before he found them, then he dived into the lock chamber and checked himself against the airlock’s outer seal, which was already beginning to open.

Fighting desperately not to inhale, he watched the crescent of yellow, foggy light widen as the seal opened. Some of the yellow fog eddied through, stinging his eyes so badly that he had to feel rather than see when the seal had opened wide enough for him to throw the objects into the alien rescue pod. Then he backed quickly out of the lock chamber and closed the inner seal behind him, dogging it shut so that it could only be opened from the inside.

Shivering uncontrollably and with his eyes streaming from the effect of the alien air, and coughing because some of it was still adhering to his hair and clothing, Martin groped his way back to the sleeping bag.

He felt Beth’s hands on his body, helping him in and then holding him tightly in an effort to stop his shivering. He felt her fingers moving gently against his eyelids, as if he were a small, hurt child and she his mother brushing away the tears. He blinked several times and found that he was able to see her, and the way she was looking at him. But all she said was, “The rescue pod is moving away. What the blazes did you do back there?”

“Good,” Martin said, smiling for the first time in many hours. “I think we’ve cracked it. I threw them a water bulb with a few drops still in it, and the empty food container, and made it clear that we did not want them to get any farther into the ship. If they put those samples into their analyzer, they should be able to learn enough about our metabolism to mount a proper rescue. It’s just a matter of waiting a little longer.”

But he was wrong.

As Martin finished speaking the control deck lights and heating came on; the cold, stale fog they had been breathing was being replaced by air that was warm and fresh. With the return of artificial gravity their makeshift sleeping bag settled gently to the deck, and the communicator screen lit with a message.

EXERCISE TERMINATED. TEST RESULTS EXCELLENT BOTH SUBJECTS. EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT RESTORED TO EARTH-HUMAN OPTIMUM. YOU MAY RETURN TO TRAINEE QUARTERS.

They did not return to quarters, or leave the lander or the sleeping bag, for a very long time. It was during this period that what they came to think of as their First Contact took place. It was a contact which deepened and broadened and made the remaining long years of their training seem short, and it would, they believed, be maintained and strengthened during the rest of their lives.

Chapter 5

THEY were settling themselves for the first study session of what promised to be another not very exciting day, when it happened.

GOOD MORNING, read their desk displays. ASSIGNMENT INSTRUCTIONS FOLLOW. PLEASE RECORD FOR LATER STUDY.

With the appearance of the words, the wall facing them became a screen depicting in unpleasantly fine detail their supervisor and the large, low-ceilinged, and dimly lit compartment in which it lived-or perhaps only taught. It was surrounded by two-small consoles and eight untidy heaps of garishly colored material which Martin had thought at first were art objects or furniture but had later decided, after seeing the creature holding one of them close to a body orifice, were more likely to be food or collections of aromatic vegetation.

SUMMARY OF ASSIGNMENT. PROCEED TO THE SYSTEM LISTED AS TRD/5/23768/G3 AND TAKE UP ORBIT ABOUT FOURTH PLANET. STUDY IT, INTERVIEW A MEMBER OR MEMBERS OF ITS DOMINANT LIFEFORM, AND CARRY OUT PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THIS SPECIES’ SUITABILITY OR OTHERWISE FOR CITIZENSHIP.

QUESTIONS?

Martin swallowed. He knew that the feeling was purely psychosomatic, but it felt as if his stomach were experiencing zero-gee independently of the rest of his body. At the adjoining desk, Beth was putting on her spectacles. She did not need them, or any other sensory aid for that matter, because all of the Earth trainees had received the benefits of the Federation’s advanced medical and regenerative procedures so that they were as perfect physiologically as it was possible for a member of their species to be. But in times of stress, Beth wore her glasses because, she insisted, they made her feel more intelligent.

“No questions,” she said quietly, glancing at Martin for corroboration. “Until more assignment data is available, questions would consist of requests for more information.”

VERY WELL, THE PLANET IS CALLED TELDI IN THE LANGUAGE MOST WIDELY USED ON THAT WORLD. IT IS A DANGEROUS PLANET AND IS CONSIDERED SO EVEN BY ITS INHABITANTS, WHO LIVE ON A LARGE EQUATORIAL CONTINENT AND A CHAIN OF ISLANDS LINKING IT TO THE NORTH POLAR LAND MASS. TECHNOLOGICALLY THE CULTURE IS NOT ADVANCED. TELDI WAS DISCOVERED BY A FEDERATION SEARCHSHIP TWENTY-SEVEN OF YOUR YEARS AGO. BECAUSE OF GROSS PHYSICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE TELDINS AND THE SPECIES MANNING THE VESSEL, NO OVERT CONTACT WAS MADE.

QUESTIONS?

There was a very obvious question, and Martin asked it. “If direct contact could not be made because the searchship personnel were too visually horrendous so far as the Teldins were concerned, why wasn’t indirect contact tried by translated visual word displays only, as was done on Earth?”

TELDINS WILL NOT DISCUSS MATTERS OF IMPORTANCE OR MAKE MAJOR DECISIONS THROUGH INTERMEDIARIES LIVING OR MECHANICAL. DISCOVERING THE REASON FOR THIS BEHAVIOR IS PART OF YOUR ASSIGNMENT

“Then we shall be meeting them face to face,” Martin said, wondering where all his saliva had gone. “May we see one of the faces concerned?”

OBSERVE.

“No doubt,” Beth commented in a shaky voice, following a three-second glimpse of the lifeform, “they have beautiful minds.”

THE MATTER TRANSMITTER NETWORK WILL NOT INCLUDE TELDI UNTIL A FAVORABLE ASSESSMENT HAS BEEN MADE. YOUR TRANSPORTATION WILL BE BY HYPERSHIP DURING SURFACE INVESTIGATIONS BY THE ENTITY MARTIN, THE ENTITY BETH WILL REMAIN WITH THE SHIP IN A SURVEILLANCE AND SUPPORT ROLE.

QUESTIONS?

Martin lifted his eyes to stare at the monstrosity beyond the desk screen, feeling himself beginning to sweat. He said, “This… this is a very important assignment.”

THAT IS A SELF-EVIDENTLY TRUE STATEMENT. IT IS NOT A QUESTION.

Beside him Beth laughed nervously. “What he is trying to say, Tutor, is why us?”

THREE REASONS. ONE: YOU HAVE BOTH SHOWN ABILITY ABOVE THE AVERAGE BOTH AS INDIVIDUALS AND AS A TEAM. TWO: AS MEMBERS OF THE SPECIES MOST RECENTLY OFFERED FEDERATION MEMBERSHIP, YOUR KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING OF WHAT IS INVOLVED IN MAKING THIS ASSESSMENT WILL BE GREATER THAN THAT OF LONG-TERM MEMBERS. THREE: THERE ARE MANY SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE TELDINS AND THE EARTH-HUMAN SPECIES WHICH SHOULD EASE YOUR COMMUNICATIONS PROBLEMS.

“Apart from breathing a similar atmosphere,” Beth protested, “there is no resemblance at all. They are ungainly, completely lacking in aesthetic appeal, visually repellant, and…”

YOUR PARDON. I HAD THOUGHT THAT THE DIFFERENCES WERE SUPERFICIAL.

To you, Martin thought, they probably are.

YOU WILL ALREADY HAVE REALIZED THAT YOU ARE BOTH TO UNDERGO IMPORTANT FITNESS TESTS. THE VALUE OF THESE TESTS WOULD BE DIMINISHED IF I ASSISTED YOU OTHER THAN BY PROVIDING THE BASIC INFORMATION.

QUESTIONS?

“Can you give us advice?” he asked.

OBVIOUSLY. YOU HAVE BEEN RECEIVING ADVICE, GUIDANCE. AND INSTRUCTION SINCE YOU CAME HERE. MY ADVICE IS TO REMEMBER EVERYTHING YOU HAVE BEEN TAUGHT AND PUT IT INTO PRACTICE. THE ASSIGNMENT NEED NOT BE A LENGTHY ONE PROVIDED THE ENTITY BETH USES ITS BRAIN AND THE SHIP’S SENSOR AND COMPUTER FACILITIES EFFECTIVELY, AND THE ENTITY MARTIN IS CAREFUL IN ITS CHOICE AND SUBSEQUENT INTERROGATION OF THE FIRST CONTACTEE.

IT IS POSSIBLE TO ARRIVE AT A COMPLETE UNDERSTANDING OF A CULTURE FROM THE INTERROGATION OF ONE OF ITS MEMBERS. ALL THE NECESSARY EQUIPMENT IS AVAILABLE TO YOU, AND YOU HAVE BEEN FULLY TRAINED IN ITS USE. WHILE YOU ARE DECIDING ON THE SUITABILITY OR OTHERWISE OF TELDI FOR FEDERATION MEMBERSHIP, WE SHALL BE DECIDING ON YOUR SUITABILITY AS A HYPERSHIP CAPTAIN AND AN OTHER-SPECIES CONTACT SPECIALIST.

THE RESPONSIBILITY IS ENTIRELY YOURS.

The system had seven planets, and its only inhabited world, Teldi, was encircled by the broken remnants of a satellite which apparently had approached within the Roche limit and been pulled apart by the gravity of its primary. The planet had no axial tilt, and the orbit of the moon had coincided with the equator. The constantly colliding orbital debris had not yet formed into a stable ring system, so that the equatorial land mass of Teldi was regularly swept by a light, meteorite drizzle which was-seeded with enough heavier pieces to make life very uncertain for anyone who remained for long periods in the open.

“It wasn’t always like this,” Martin said, pointing at one of the sensor displays they had been studying. “That gray strip with the old impact craters all over it was an airport runway, those heaps of masonry and corroded metal could only be industrial complexes, and the rubble of what’s left of their residential area stretches for miles around. This culture must have been as advanced at least as that of pre-Exodus Earth before their moon broke up.”

“It may have been more than one moon,” Beth said thoughtfully. “The orbit and unusual clumping of the debris indicates a…”

“The difference is academic,” Martin broke in. “What we have here is a once advanced culture which has been hammered flat by meteorite bombardment to the extent that they have regressed to a primitive fanning and fishing society. Except for that polar settlement, which is virtually free of meteorites, their past technology seems to have been destroyed. The question is, where do I land?”

Beth displayed a blown-up photograph of the polar settlement along with the relevant sensor data. It was a scientific establishment of some kind, with a small observatory, a non-nuclear power source, and a well-built road which was obviously a supply route. Communicating with the inhabitants would be relatively easy, Martin thought, because the astronomers among them would be mentally prepared for the possibility of off-world visitors. But they would not be typical of the population as a whole.

An assessment should not be based on a species’ intellectuals alone. Ideally he should talk to the Teldi equivalent of a well-educated man in the street.

The landing site finally chosen was by a roadside some ten miles from a “city” which lay on and under the floor and walls of a deep, fertile valley on the equatorial continent.

“And now,” Beth said, “what about protection?”

For several minutes they discussed the advisability of using the ship’s special protection systems while he was on the surface, then decided against them. He had to make contact with a technologically backward alien, and he would do himself no good at all by frightening it with gratuitous demonstrations of supersedence.

“All right, then,” he said finally. “My only protection will be the tender’s force shield. I won’t carry anything in my hands, and will wear uniform coveralls and an open helmet with image-enhancing visor, and a Teldin-type backpack with a med kit and the usual supplies. The Teldins seem pretty flexible in the matter of clothing, so I would be displaying my physiological differences as well as showing them that I was unarmed.

“The translator will be in my collar insignia,” he went on, “and the helmet will contain the standard sensor and monitoring equipment, lighting, and the translator by-pass.

“Have I forgotten anything?”

She shook her head.

“Don’t worry about me,” he said awkwardly. “Everything will be just fine.”

But still she did not speak. Martin reached toward her and carefully removed her glasses, folded them, and placed them on top of the control console.

“I’m ready to go,” he said, then added gently, “sometime tomorrow…”

Martin made no secret of his landing. He arrived at night with all the lander’s external lights ablaze, and came in slowly so as not to be mistaken for one of the larger meteors. Then he waited anxiously for the reaction of the inhabitants and authorities of the nearby city.

With diminished anxiety and growing impatience, he was still waiting more than a full Teldin day later.

“I expected crowds around me by now,” Martin said in bewilderment. “But they just look at me as they pass on by. I have to make one of them stop ignoring me and talk. I’m leaving the lander now and beginning to move toward the road.”

“I see you,” Beth said from the hyper ship, then added warningly, “the chances of you being hit during the few minutes it takes you to reach the protection of the road are small, but even the computer cannot predict the impact point of every meteorite.”

Especially the rogues which were the result of collisions in low orbit, Martin thought, and which dropped in at a steep angle instead of slanting in from the west at the normal angle of thirty degrees or less. But the odd behavior of the satellite debris which fell around and onto Teldi, and which so offended Beth’s orderly mind, faded from his mind at the thought of meeting his first Teldin.

It would be a member of a species which had advanced perhaps only to the verge of achieving space-flight, and which still practiced astronomy in their dark, polar settlement. Such a species would have considered the possibility of off-planet intelligent life. Perhaps the idea might now exist only in the Teldin history books, but an ordinary Teldin should be aware of it and not be panicked into hostile activity by the sight of a puny and obviously defenseless off-worlder like Martin.

It was a nice, comforting theory which had made a lot of sense when they had discussed it back on the ship. Now he was not so sure.

“Can you see anyone on the road?”

“Yes,” Beth said. “Just over a mile to the north of you, heading your way and toward the city. One person riding a tricycle and towing a two-wheeled trailer. It should be visible to you in six minutes.”

While he was waiting, Martin tried to calm himself by examining at close range a stretch of the banked rock wall which ran along the side of the road. Like the majority of the roads on Teldi, this one ran roughly north and south, and the wall protected travelers from the meteorites which came slanting in from the west.

The banked walls were on average four meters high and built from rocks gathered in the vicinity. The roads were rarely straight, but curved frequently to take advantage of the protection furnished by natural features such as deep gullies or outcroppings of rock. When east-west travel was necessary, the roads proceeded in a series of wide zig-zags, like the track of a sailing ship tacking to windward.

Suddenly there was the sound of a short, sharp hiss and thud, and midway between his lander and the roadside there was a small, glowing patch of ground with a cloud of rock dust settling around it. A meteorite strike. When he looked back to the roadway, the Teldin was already in sight, peddling rapidly toward him and hugging the protective wall.

Martin walked to the outer edge of the roadway to get out of its path. He did not know anything about the oncoming vehicle’s braking system, and it was possible that he was in greater danger of being run over by a Teldin tricycle than being hit by a meteorite. His action could also, he hoped, be construed as one of politeness. When the vehicle slowed and came to a halt abreast of him, Martin extended both hands palms outward, then let them fall to his side again.

“I wish you well,” he said softly. Loudly and clearly and taking a fraction of a second longer, his translator expressed the same sentiment in Teldin.