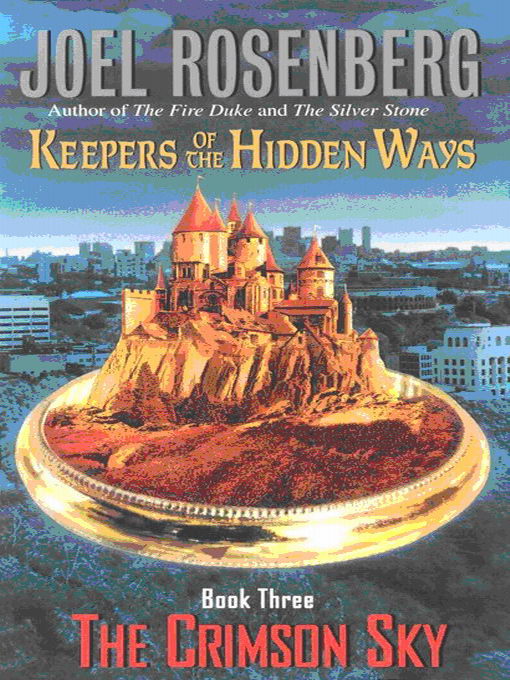

The Crimson

Sky

Keepers of the Hidden Ways

Book III

Joel Rosenberg

Content

News

Prologue

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Part Two

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

L ‘Envoi

News

Big Bang,

Big Crunch, Big Headache?

by Elise Matthesen Special to The Gleaner

09-MAR-98 Hardwood ND USA

The universe will end. Not soon—perhaps it will take another two hundred billion years or more—but the universe will end.

Recent findings from astronomers have left scientists with that uncomfortable conclusion. Five separate teams of scientists from Princeton, Yale, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Harvard have all recently announced studies that show that the universe, which began with the cosmic explosion called the “big bang” approximately fifteen billion years ago. will expand forever, until nothing remains throughout space but widely scattered hydrogen atoms and cold rocks.

Scientists investigating the possibility of a future “big crunch,” where all the matter in the universe combines to form a single extremely dense package and then blasts outward in a rerun of the big bang, discovered that the universe contains only twenty percent of the mass needed. The universe is “open” and will not “close,” they say.

The results of these years-long studies are provoking an uproar among those scientists wedded to the steady state hypothesis, the notion that the universe is “closed.” The skull-splitting question: if the steady state hypothesis is true, at least eighty percent of the matter in the universe is undetected and undetectable. Where is, they ask, the missing eighty percent of the universe’s mass necessary to bring on the next big crunch/big bang cycle?

Dr. Erwin Rice, director of the Astronomy Department at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, is unsurprised by the findings—or the furor. At a Macalester College debate in Minneapolis last week on the implications of the study, Rice said, “These steady staters believe in a universe that goes back and forth like a yoyo. No grand design—it’s a video game: push the big bang button and start over.”

Rice calls the steady staters’ theories “wishful thinking and sloppy science—like running another study if you don’t like the results you got the first time.” Rice says the five studies are “jointly and severally conclusive” and says, “It proves what we already know.”

Assistant Professor Kim Coleman of the University of Minnesota‘s Astronomy Department, speaking at the same gathering, said the study doesn’t answer as many questions as it raises. “Where did the matter go? Why can’t our instruments detect it? If it’s gone, when and how did it get converted to energy—and why haven’t we picked up the traces of such a process? If the steady state theory is correct, how does the necessary mass reassemble itself?” asks Coleman. “If it isn’t true, then what happened before the big bang?”

“That’s a meaningless question, scientifically,” Rice interjects. “But if the evidence states the big bang was a singular event that will not be repeated, how many alternative studies can we con the taxpayer into funding?”

Coleman admits that some of the hypotheses suggested to shore up the steady state model are “pretty far-out”—ranging from new types of interference that block the effects of gravity to pocket universes straight out of sci-fi novels.

“Or maybe the cat knocked it under the couch,” jokes Rice. “We’re talking enormous amounts of lost matter here—at least four times all the measurable matter in the universe!—not some little key chain doodad you can leave lying around someplace and forget!”

The Reverend Georges Friedmann, who holds a Ph.D. in Astronomy from Cal Tech, as well as a Master of Divinity from Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, and who teaches two classes in astronomy each semester at Macalester in addition to his duties as associate pastor at Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church in Minneapolis, finds the controversy both fascinating and amusing. “If the universe is open, and proceeds from a beginning, I think the religious implications are obvious,” he says, smiling smugly. “If you find my smile smug, you have gotten my point.”

“Well, maybe you should have your Jehovah check his pockets,” answers Coleman. “The fact is, we won’t know what happened to it until we look further. And, not having certain funding advantages—” Debates may end in rancor, but the question remains: If the steady staters are right, and the universe is an uncreated, self-regulating series of big bangs and big crunches, then where’s the missing mass?

Whoever borrowed that extra matter had better put it back, according to Rice, or the steady staters are going to be “very, very unhappy.” Rice waggles an admonitory finger. “”And very, very embarrassed, when study after study shows the same result: the universe is open.“

Friedmann is more conciliatory. “It’s long been a fundamental cornerstone of science that the existence of an extra-normal Creator is untestable, and as a scientist, I have to say that it still is. But as a man of God, I’m not entirely displeased that the cornerstone seems to be crumbling just a little.”

Professor Coleman declined comment.

Prologue

The Faerie Ring

Winter was coming.

She could smell the frost in the air, mingled with the tang of ozone. The cold, wet wind rattled the few remaining brown leaves that still clung in dead desperation to the branches of the old oak. The lightning flashed, and the thunder boomed not far away upwind, high on the eastern ridge where the road to the Dominions twisted like a silver thread through the gray and the green.

The cold didn’t bother her, even though all she wore was a knee-length shift, belted tightly to accentuate her slim waist and the full breasts and hips that were only sometimes in style, but always popular with men down through the ages.

At this altitude, soon there would be snow, even this far south, but that wouldn’t be more than a mild inconvenience—for her, at least—if she decided to make the climb to forage again.

Lighting flashed and thunder boomed, yet again.

The lightning and thunder didn’t bother her, either; in fact, they amused her.

Boys will be boys, after all.

A human eye wouldn’t have caught it, but the lightning didn’t flow down from the dark clouds overhead; instead, it splattered outward and up from a single point of impact in the mountains, white-hot sparks fountaining up and out from a blacksmith’s strike against his anvil.

The woman the locals called Frida the Ferryman’s Wife grinned to herself as she stooped to part the soft moss at the base of the old oak tree, and reached her hand through the musty humus into the tight-packed, chalky soil, her fingers probing carefully, gently, tenderly. They emerged filthy, the dirt packed hard into the creases of her knuckles and even under her short nails, but cupping yet another truffle the size and shape of a baby’s fist: brown like old wood, veined in black and white, covered in coarse polygonal warts, each with a tiny depression at its summit.

They were rarer here in the south, but they often had rings of brown mushrooms up in the Dominions. A drifting spore, too small for human eyes to see, would fall to the ground and find just the right combination of dank and dark to grow and send out shoots; and from those shoots would grow brown-capped mushrooms, in a ring perhaps two, three, four paces across.

Overnight, in a meadow, perhaps, or even on the green, green grasses of the Cities, a perfect circle of mushrooms would appear, as if by magic.

Fairy rings, the children called them, and they would shy away. There was something chilling in their sudden appearance, in their unnatural regularity.

Some fairy ring mushrooms were quite tasty, others, often similar in color and shape, were quite deadly. Perhaps an apothecary would be summoned to identify them as wholesome, taking a share as his pay and a bite as his proof. Or perhaps not.

But, as with all things, the center would die. Still, the shoots would live, each to send out its own shoots, to form rings of rings, and then rings of rings of rings until, finally, the circle was too large and subtle to be detected by ephemerals, who could no more detect the shape of an ancient fairy circle than they could watch a high, jagged mountain range slowly crumble, writhe, and wither into shrunken old age, like a snake with a broken back.

It was all a matter of perspective and patience. These were useful attributes even for an ephemeral, and it was difficult to get through even one’s first few centuries without developing both.

She added the truffle to her basket and considered for a moment whether or not to follow the ring. The next truffle should be over… there.

Let it lie, she decided. If she sliced them paper thin, as she preferred, there were more than enough to line the skin of the goose that was, even now, hanging from the meat-hook in the cottage she shared with the Thunderer, and even a few to pop into the drip cup of fat, to sizzle and smoke for a few moments, before she would pop them in her mouth.

Again, thunder rang out. Arnie’s explanation was that he had seen three Vandestish patrols out this way in recent weeks—and, quite certainly, he had: her sharper eyes had spotted seven—and that it was only reasonable to show a little force, to make the sky rumble a trifle and the land shake ever so slightly, if only to remind them who was who, and what was what.

That was the truth, and nothing but the truth, but it was not the whole truth.

She grinned.

It was the way of women in general and a fertility goddess in particular to understand that men, be they ephemerals or gods, really never stopped being boys. She had seen this sort of thing for the first time when the world was young, and more times than she cared to count since, but it still amused her.

A boy with a new toy was always the same, whether it was a toddler with a pair of round stones that he had just discovered made a delightful crack! when slammed together, or a pubescent young boy with his first real orgasm, or a man in his sixties who found that he was one who could wield Mjolnir, Murderer of Miscreants.

Boys: they had to play with their toys.

The wind picked up. Winter was coming.

She picked up her basket and hurried up the road to the cottage.

Winter was coming. Perhaps even the Fimbulwinter? Not yet, she thought. Not yet. Freya shivered, but not from the cold. Please. Not yet.

Part One

Hardwood, North Dakota

And

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Chapter One

Something In The Air

Torrie Thorsen first picked up the scent just east of Lyndale, on Lake Street. He had gotten off the Number Four bus—his car was buried in S-Lot under a bank of snow from the snowfall of two nights before, and he hadn’t had the time to dig it out, not yet—at Lake and Lyn, and thrown his book bag over one shoulder, and his gear bag over the other.

He considered stopping for some takeout at the Greek place at the corner—Maggie liked their gyros, and Torrie liked the taste, if not the name, of their “Cheeseburgerop-oulis”—but it was kind of cold out, and he was dressed for the city, not for the country, and Maggie and her roommate kept their apartment warm, and since she was expecting him there would be a fresh pot of coffee on, and—to be honest, and Torrie Thorsen made it a policy to at least always try to be honest with himself—the sooner he got into her apartment and out of his coat, the sooner he could get Maggie out of her clothes and into her bed and get himself into Maggie, and if that sounded awkward and crude even within the privacy of his own mind—and it did—he wasn’t going to say it that way out loud.

Even if it was true.

Food could wait.

Dirty snow stood piled high, covering the curb, the little red flag on the fire hydrant peeking out. In the summer, it looked like an antenna, as though city fire hydrants were really radios in bad disguise, maybe planted by Boris and Natasha, broadcasting hidden messages to the Pottsylvanians.

But in the winter, it was just a piece of red plastic.

The smell of winter was in the air: diesel fumes from the buses mixed with the scent of cold, and with the mouthwatering smell of sizzling gyrobeast on the rotisserie at the Greek place that just had to be deliberately pumped out at street level…

… and with a distant foul smell that was vaguely familiar, although he couldn’t place it.

He shook his head and sniffed again.

It was gone, replaced with the rich meaty scent of roasting peppers and maybe some lemongrass.

You got a good mix of tantalizing scents in the air in this neighborhood, what with a half dozen cheap little restaurants—most of them quite good—vying in different ethnic dialects for the local palate and wallet.

There was a Vietnamese place down half a block that had a remarkable way with those crisp egg rolls filled with cellophane noodles, crunchy cabbage, and spiced shrimp; a hole-in-the-wall Ethiopian restaurant that served horrid-looking but wonderfully spicy glops of indeterminate mush that you swept up with pieces of warm flatbread; and the fryolators at that Arabic café always had something tasty going.

Maybe it was just a bad day for the shashlik.

He sniffed the air again, and picked up his pace. Nothing this time.

He shrugged. Probably nothing at all.

He frowned to himself. I’m just being silly. It was probably just that he didn’t like having to make this trip. Maggie had moved off campus and to an apartment on Bryant, just off Lake. Torrie didn’t quite understand it, but he was more than sure he didn’t like the way it cut into her time.

The amount of time you had to spend to keep an apartment clean, to go shopping for groceries, and to do all the other stuff that went with off-campus life, well, that time came out of your schoolwork time budget, your social life, or your time in the gym, and neither he nor Maggie was willing to cut down on their practice time, and she wasn’t willing to slack off on any of her courses.

And then there were her evenings on the phone at the Rape Hotline, and her shopping expeditions with that roommate of hers and her circle of friends—

—all of which meant Torrie was seeing even less of Maggie than he had since well before they had taken time off from school—not to mention the months they’d spent traveling together—and he really didn’t like that.

Not that what he liked necessarily made a difference, but he had sort of assumed that after spending time bouncing around Europe—and Tir Na Nog—together, the two of them would move in together after school was finished, and work out something even less formal in the interim.

And then she had taken an apartment, complete with roommate, without so much as hinting that that was what she had planned. The first inkling he had had about it was when he had checked in at her former dorm and was given her forwarding address.

Some hint.

Not so much as a word in advance—that was very, very Maggie.

He was more disappointed than angry. This was Torrie’s senior year, after all, and he finally had a single room—not that Ian had ever had a problem sleeping on the couch in the dorm living room—and while she grudgingly kept a couple of changes of clothes in his bottom drawer for those rare occasions when she stayed all night, that was about the limit to which she was willing to move in.

Women, he thought. Can’t live with them—not when they won’t let you.

Fact is, he liked just being around Maggie, and with Ian on a leave of absence from school that was probably going to be permanent, she was the only person in town that he could really talk to without watching himself.

And there was more to it.

They’d been through some things together, her and Ian and him—and Mom and Dad and Uncle Hosea, for that matter. You sweat and bleed and shiver in fear enough with somebody, and they’re part of you, and you’re part of them, in a way that transcends any ordinary understanding.

Call it magic; Torrie Thorsen had no objection to magic.

He grinned. And that felt kind of nice, even if he had to share that special closeness with Maggie, with Ian, and his family. At least, he didn’t have to share every—

There was that smell again. Bitter and acrid, but distant. Like …

… like he couldn’t remember what.

You learn a lot of things on a fencing strip, and one of the first you learn is balance, although Torrie had learned that from his father a long time before he had ever set foot on a fencing strip. The three pillars of fencing were balance, timing, and space, and if you didn’t have all of those down solid, there was no point in even thinking about strategy, because somebody with whatever attribute you were missing could score on you just about nine times out of nine.

He spun around, quickly, his weight on the balls of his feet, not sliding at all, despite the slipperiness of the sidewalk.

The middle-aged woman in the heavy coat, weighed down with the canvas Byerly’s bags, let out a gasp, her eyes wide, and dropped one of the bags.

Paper-wrapped packages of meat fell to the sidewalk, cans rolled into the snow, and the small glass bottle of Crystal hot sauce bounced once, twice, three times on the ice before deciding not to break after all. Which was just as well. Torrie would have had to offer to pay for it, and this being the city, that would have been awkward.

“I’m sorry,” he said, bending over to help her put the groceries back. “I thought I heard something, and I kind of, I don’t know, I kind of twitched.”

“That was different,” she said, her mouth twisting into a smile.

He brushed snow and grit off the bottle of Crystal sauce and put it back in her bag.

“Can I carry one of these for you?” he asked, reflexively, then flinched. You just didn’t do that in the city.

But surprisingly, she nodded. “Sure—you bet.” She smiled knowingly as she handed him one of the gray canvas bags. “You can take the boy out of the country, but not the country out of the boy, eh?”

“It shows, does it?” He slung both of his bags over his left shoulder and kept step with her.

“Well, yes, it does.” She smiled again. “But it’s very sweet.” She took the small, sort of mincing steps that old people did when they walked on a slippery surface, but at least she took them quickly enough that he didn’t have to slow down too much. “Whereabouts are you from?”

“Hardwood, North Dakota.”

She frowned, as though she had expected the name to be familiar.

Lady, it could have been famous, but we like things the way they are, thank you very much.

Hell, even Hatton, with half the population, had its famous native son in Carl Ben Eilsen, an early barnstormer, but nobody famous had ever come from Hardwood. Which was fine, really, and the way it should be, although there were times and ways in which that grated on Torrie’s nerves.

“Hmmm … no, I guess I never heard of it,” she said. “I’ve got an uncle who lives in Bismarck—is it anywhere near there?”‘

He shook his head. “No. Other side of the state, about forty miles out of Grand Forks.”

“Ah: East Dakota.” She nodded. “That’s what my uncle Ralph always used to say, that the Dakotas were divided the wrong way. That they should have been East and West instead of North and South.”

Torrie had never thought of that before, but it did make sense, sure—the west was badlands and mountains, the east was flat farmland. “There’d be some sense to that.”

“Yup. So, do you like the city?”

“Well, it has its points.”

“But you miss Hardfield.”

“Hardwood. And, yes, actually I do.” Minneapolis was a nice enough city, as cities went. But it was a city—it was filled to overflowing with strangers.

“I see.” She gave him a grin that told him she thought she knew what he was thinking, and she probably did. “Didn’t anyone ever tell you that you can’t ever go home again?”

“Well, yes, I have heard that, actually.” But you didn’t need to believe everything you heard, after all. Torrie would have shrugged, but that would have made his gear bag slide off his shoulder, and he didn’t want that.

What he did want to do was to ask how much further she was going, and that was awkward.

Not that he wouldn’t carry the bag wherever it was (and it couldn’t be far enough for it to be a problem for him, or she wouldn’t be carrying so much—it wasn’t like she was a young woman—she was at least forty, forty-five); he just wanted to know.

But this was the city, and you didn’t ask a woman where she lived, for fear she’d think you’d be lurking outside around her house all night, baying at the moon or something.

He was thinking about the right way to ask how far away her place was without asking where it was when she turned left at the camera store onto Bryant Avenue.

He wouldn’t have been very surprised if she had climbed up the steps to the fourplex where Maggie lived—he didn’t really know any of Maggie’s neighbors; this was the city, after all—but she gestured at the next building down, and reached out her hand for the bag.

“Thank you for your help, but I think I can take it from here,” she said.

He had lived in the city long enough to know that she meant I’d rather you not walk up to my door, and that that wasn’t just a figure of speech meaning Can you carry the bag all the way into the house? as it would have been at home, and he was only very slightly surprised when he noticed that she had a little blue pepper-spray canister on her keyring, which was already in her hand, and probably had been in her hand all the while they were walking and talking together.

Well, good for her, he thought, as she walked up the stairs, glancing once over her shoulder to make sure he was moving away.

Which he was.

It made him feel funny. No, not funny: bad. Shit, a woman didn’t need pepper spray—or a knife or a gun or a squad of cops, for that matter—to prevent Torrie Thorsen from committing robbery or God-knows-what, and it hurt to think that that didn’t show on his face.

No. That wasn’t fair, and Torrie tried to be fair, even in the privacy of his own mind.

Ted Bundy had looked like the clean, all-American boy, too. And the city wasn’t the country. You could pretend it was, if you were foolish enough. You could leave your car or your room unlocked, or not worry about what time of night it was when you went out, or assume that any footsteps behind you were somebody you knew, and you—

And you would be burglarized, mugged, robbed, and murdered, more than likely more than once.

He grinned.

Except for the murdered part, of course.

He had keys both to the outside door and to Maggie’s front door, but he rang the bell instead. Her roommate had a habit of walking around with what Torrie thought of as insufficient clothes, and that embarrassed him when he came upon it suddenly.

It wasn’t like she looked all that good in just panties and bra, either.

The wind picked up, driving the cold into him, as he waited, reconsidering digging into his pockets for the keys. A quick beep could have meant Throw on some clothes, I’m on my way up, after all.

And then there was that smell again. Still distant, but bitter and acrid and harsh, and … what was it? It was familiar, and it almost had the hairs on the back of his neck sticking up, but—

He just couldn’t place it. Damn.

He was still considering when he heard her feet thumping on the stairs.

Maryanne Christensen opened the inner door as he opened the outer one. Her hair was up in some sort of complicated ponytail type thing that left the back of her slim neck bare, and her face was slightly flushed at the cheekbones.

“Come in, come in,” Maggie said, then turned and headed back up the stairs. He didn’t blame her for hurrying. The hallway was unheated—the landlord never turned on the hall radiators, apparently—and she was dressed only in black leggings and a long, loose red silk shirt they had picked up off the Bois de Bologne.

He enjoyed the view as she moved quickly back up the stairs, taking each step with a bounce. Some would have thought her too skinny, but she was built along what his mother would have called greyhound lines, and while her muscles didn’t bulge, a pleasant combination of heredity and exercise had given them a tone that made her worth watching from just about any angle.

Certainly including from behind.

If she’d caught him staring, she would have glared, the way she had at Ian that one time. Ian had just smiled and said, “Hey, I like girls. Sue me.” And Maggie had decided to take that with a smile.

Hey, if she didn’t want to be looked at, she could dress ugly.

“I was starting to worry,” she said. “I thought you said you’d be here around one.”

“Well, I did say ‘around’ ” He glanced at his watch—2:17, it said; he was later than he’d thought—as he followed her down the open hallway to her open door. Maybe he should have some words with her about answering the door with pepper spray in hand. It was the city, after all.

“I took a little longer at the library than I thought I would,” and never mind that part of the time was spent chatting with the new assistant in the reference department, who wanted to know what the fencing gear case was about, and who, underneath a remarkably long set of lashes, had a pair of very large and very brown eyes that a guy could enjoy spending a few minutes looking into, “and then I decided to take the bus instead of digging my car out.”

“Well, good,” she said, taking his bags and coat, then unceremoniously tossing them onto the couch in front of the spool table. “Long as you’re here, you can give me a hand with this for a few minutes. It’s not a rush, but I need to have it taken apart in two weeks.”

The apartment was built along standard South Minneapolis railroad-car lines: one long room, cut in half by a craftsman-style built-in mirrored buffet that Torrie had identified as Stickley, the kitchen built into the hall that opened on the bedrooms, beyond where the buffet stood as the outer wall to Maggie’s room.

The buffet, though, was partly disassembled, the drawers stacked to one side, its joints and innards lying exposed, as though it were some wooden creature, disembowled by somebody in a rush.

“That’s new,” he said.

She nodded. “My landlord offered me a break on the rent if I refinish the built-in.”

Torrie raised an eyebrow.

She smiled. “And your uncle Hosea offered to come down for a week and do the stripping and refinishing and rebuilding for me, when I called him to ask for some advice, and maybe some help.”

Torrie smiled. “Just don’t let him go wild with abditories.”

“Eh?”

“Nothing. Never mind.”

It was the sort of piece Uncle Hosea would love to put hidden hiding places in. This buffet was similar enough to the one in the Guest Room at home to receive the same treatment: a silent little pressure lock hidden beneath each of the door hinges, holding a drop-down compartment in place. Put a piece of paper inside each of the hinges, press the two glass-paneled doors shut hard enough to make the hinge-plates flex just enough to set the pins correctly in the keyway, then slide open the top drawer—just soooo far, and no farther—before a quick thump on the top of the buffet, and a two-inch-thick inner drawer would drop down.

That abditory, the one in the buffet at home, contained a set of spare passports and other papers that might be useful under extraordinary circumstances. Other abditories, like the compartment under the front hall stairway, contained survival kits, or weapons, or money, or things as prosaic as the emergency roll of toilet paper.

But Uncle Hosea often built such things just as an art form, like the tiny one in Mom’s bathroom for her tampons, which Torrie had only found accidentally, while clearing hair out of the sink’s trap. And back when Torrie was a kid, Uncle Hosea had built him a secret compartment in the side of his closet that was just the perfect size for a stack of Playboys.

Giving Uncle Hosea a week to put this buffet back together was like locking a kid up in Toys “R” Us for a night.

Well, let him have his fun.

She gestured at the tools spread out on the canvas drop cloth covering the floor. “All I have to do is take it apart without doing much damage, and I can do that.”

“I did have other ideas as to how to spend the afternoon,” he said, reaching for her.

“You did, did you?” She grinned as she wrapped her arms around his waist. “Hmm … well, it appears you did. I think we ought to do work, food, and some studying first. We’ve got the place to ourselves—Deb’s spending the next couple of nights over at Brian’s, and I’d be surprised if she even stops by to pick up her mail. So, what would you think about us doing some grunt work, then some studying, then grabbing a quick supper and see what happens after that?”

“Is that one of them there rhetorical questions?”

“Yup.”

“I never liked rhetorical questions.”

“Work first; then food. And then, well, maybe we’ll see. You work better when you’re horny.” Her smile turned her maybe into a promise, and a quick kiss sealed it.

“I think my good nature is being taken advantage of,” he said as she stepped back. He dropped his jacket and then opened up the toolbox, giving in with as much grace as he could muster, which wasn’t much.

“Work.”

He made a low rumble in his throat.

“Don’t growl.”

“Sorry.”

He didn’t like it, but he didn’t have to. But still, shit, Maggie didn’t need to get a break in the rent. She didn’t need to have a roommate. She could have afforded the apartment all by herself. And even if she couldn’t, she did have a boyfriend who could have and would have picked up the rent without worrying about it.

Torrie sighed. He’d just as soon pay the rent—no, he’d rather have paid the rent on a place closer to campus, for the two of them.

But no. No, it wasn’t about money. Maggie’s parents were taking care of her rent and tuition, and Torrie’s mom had invested Maggie’s share of their Dominion gold for her. It wouldn’t make her rich, but it would take care of rent and food and such indefinitely, if needed.

It wasn’t about money. Most things about money weren’t really about money—Torrie had learned that from Ian Silverstein.

For Maggie, this was about doing things the right way, and it was important to her to do things the right way. Apartments near the U were undersized, and the ones that had any character at all were hideously overpriced. So she had arranged her class schedule to pack her classes close together, and had looked over in South Minneapolis, near the bus line.

Two-bedroom apartments tended to have decent-sized kitchens and living rooms, and rented for significantly less than twice as much as one-bedroom ones.

And if you had a two-bedroom apartment, not renting out the second bedroom would simply be wasteful, and renting it to your boyfriend—who could afford it even more easily than you could—would smack of him picking up your rent, and that was where this whole thought started, with Maggie not being willing to let him do that, because it wasn’t about money.

Damn.

The nice thing about money was that that MacKay guy—Harry? Ralph? The guy who owned that envelope company and gave all those speeches—was right about it. If you had a problem that you could solve—not put off, but solve—by writing a check, you didn’t have a problem.

All you had was an expense.

“Don’t pout,” she said. “You look about ten years old when you pout.” She came into his arms for a quick kiss, hesitating for a moment before her lips parted and her tongue was warm in his mouth. His left hand cupped her bottom, pulling her toward him, while his right sought her breast.

But she pushed him away.

“Later,” she said. “Maybe.” She smiled as she stroked a finger down the front of his zipper. “Delayed gratification is the best kind.”

Well, there were times when no didn’t mean no, but this wasn’t one of them.

Damn. I should have stopped at the Greek place. A Cheeseburgeropoulis would go down well, right about now. And it was looking like food would be about the only goddamn thing that would be going down in the near future.

“Coffee?” she asked.

“Fresh pot.” He sniffed. Yes, that was good, rich, dark-roasted coffee, and it wiped out any trace of that strange scent in the air.

What had that been? It was familiar, and disquieting, but he couldn’t place it.

He sighed, and reached for a chisel.

Chapter Two

The Hidden Way

Ian Silverstein shrugged into his parka and stepped into his boots, then bent to lace them up the front. He was still enough of the city kid that it felt strange to be wearing boots that you wore instead of, rather than over, your shoes, but going around in your stocking feet wasn’t an embarrassment in Hardwood anywhere that was too nice to wear snowy boots.

Hell, he had a cheap pair of Chinese slippers in one of the pockets of his parka, but he’d never found the occasion to use them, and he was thinking about taking them out and putting them in permanent storage in the closet. He couldn’t wear them around the house, after all, not if anybody came over—it would make it look as though he expected everybody else to do the same.

Boots laced, he opened both the heavy wooden front door and the storm door to take a quick sniff of the frosty air, shivering at the almost arctic blast that answered him.

Hmm … maybe he should put up one of those outside thermometers.

But sniffing the air was the way that everybody in Hardwood seemed to decide how many layers to put on, and that was the way Arnie Selmo had always done it, and that was the way Ian would do it, too.

It was probably silly, but it was part of feeling like he belonged here.

He looked around the room to make sure he had shut off the lights. That was another small-town thing he was getting used to: you shut off the inside lights when you went out, perhaps leaving the porch light on to light your way back in, but not leaving on lights and a TV or a radio to dissuade burglars. That was wasteful.

He had made changes around the house, as a friend had suggested and as Arnie had given permission, but each change, no matter how minor, had been deliberate and calculated, something he could justify to Arnie, and something that, through some strange coincidence, just happened to remove yet another reminder of Ephie Selmo.

The wall between the kitchen and the living room had held Ephie’s knickknack shelves, so he and Thorian Thorsen had knocked down the wall when they redid the kitchen, dining room, and living room all into one very homey sort of room, half carpeted, half tiled, the two sections separated by a counter that stood where the wall had been. You could cook dinner and chat at the same time, or stretch out on the battered old couch with a newspaper and a cup of coffee while keeping an eye on a simmering pot of soup.

And if doing that made this look less like Ephie’s house, well, there was no harm in that, as long as he had another explanation.

In doing all the construction, he had learned more about working with joists and microlams and Sheetrock and electrical cabling and phone wires than he had ever expected to, but Hosea was always available to help out, and Thorian Thorsen was usually available to help out, and when one of them didn’t know how to do something, or when there were four or more pairs of hands needed instead of two, there was always somebody available, if you had the time to wait.

Ian had time.

Besides, usually there were other neighbors to help out—he didn’t have to do a lot of waiting. If you worried more about making yourself useful and less about whether or not you were getting the better of the deal, it worked out okay, most of the time.

Ian Silverstein, he thought to himself, you’re developing patience.

You had to, to live in Hardwood. Probably true in any small town.

And now, a counter stood where the wall that had held the shelves where Ephie Selmo’s collection of little metal bells, small glass sculptures, and other knickknacks had stood for something like half a century.

Each item had been carefully cleaned, then wrapped in newspaper and put away, the boxes properly labeled and stashed in the attic. Ian wasn’t sure what Arnie needed, but whatever it was, he didn’t need constant reminders of his late wife. He carried enough of those inside him.

Ian yawned. It was still too damn early. Another cup of coffee was not a good idea—he’d be drinking coffee all morning.

And, besides, there was another way. Maybe. At least … there should be another way.

No harm in giving it another try.

He lifted the hem of his parka to get at his right-hand pocket, and he came out with a plain gold ring, too thick to be a wedding band but heavier than it looked.

He slipped it first over his thumb, and then his ring finger; it fit both perfectly, although his thumb was visibly thicker. It didn’t seem to change size—at least he couldn’t see it do that. He should be used to that now, but maybe there were some other things that he should be used to, as well.

He thought, I am awake. Which was true, although he was still sleepy. But the idea was not to be just awake, but wakeful, and he hadn’t slept well last night, and it was too damn early in the morning …

No. Thinking that way wouldn’t solve anything.

He yawned. “I am awake,” he said. “I am awake, and alert, fresh for the morning, all traces of sleepiness banished from my mind and body.”

He willed it to be so …

And yawned again.

He grunted. It wasn’t working. But it was important that he be alert, and he would be. He leaned back against the doorpost as he closed his eyes painfully tight, until bright spots danced in the inner darkness.

Ian took a deep breath, and let half of it out. He was awake, and he was alert, and he was fresh and ready for the morning, all sleep banished …

… and the ring pulsed against his finger, painfully hard, like a boa constrictor’s embrace: once, twice, three times before it stopped.

It felt warm. And he felt kind of silly. Why had he bothered to use the ring again? It wasn’t like he was sleepy or anything. It would have been wasteful if the ring’s virtue could be exhausted.

And if my grandfather had had tits, the old Jewish saying went, he would have been my grandmother.

“And that would have made my grandmother a lesbian.”

That was Ian’s own addition.

Ian slung his rucksack over one shoulder, and the oversized pool cue bag containing Giantkiller over the other, and he stepped outside, closing the door behind him, still enough of a city boy that he had to remind himself not only not to try to lock it but also that he couldn’t—in Hardwood, probably nobody knew where the key to their front door was.

Across the street, there was a light on in Ingrid Orjasaeter’s living room, and the movement of a shadow against the drapes said that she was up and around. Which was good. Old Ingrid was a notoriously early riser, and Ian would have worried if he hadn’t seen any signs of life in her house. Not that it would be a problem to stick his head in the door and call out to her—it wasn’t like it would be locked or something.

Lock your front door?

Why would you do that?

What would happen when a neighbor needed to get in? Your neighbors never needed to get in? What kind of person are you, a city type?

The west wind picked up, driving a fine mist of hard snow up and into the air and his face.

He shivered and then set out down the road. The snow squealed beneath his boots as he walked, and he gradually picked up his pace so that the high-pitched sounds kept pace with the dull thud of his heartbeat. Movement could keep you warm, or at least less cold, although too much movement could start you sweating, which could freeze you to the bone in a matter of minutes. The trick, which had taken him quite a while to learn, was to ratchet up your level of effort slowly and carefully. It was just like the gym; you didn’t go into a full workout without a good, solid warm-up before.

Although here and now the punishment for overdoing it wasn’t so drastic. You could pull a muscle or hurt a tendon in the gym, and for Ian that would have meant going without tutoring fees for several hungry weeks; here, all that would happen in town at least was that you’d get painfully cold.

It was bitter out, and it wasn’t going to get any warmer, not for several hours. What was that bit from that old Crosby, Stills, and Nash song? Something about it being the darkest time just before the dawn? Well, that wasn’t true, except maybe metaphorically—and the coldest time of day was usually just after dawn, during that hour or so before the air and ground had a chance to build up and hold whatever heat from the sun it could.

And anybody who didn’t think there was a difference between five below, fifteen below, and thirty below probably had never set foot on squealing snow in all his life.

He pulled back his sleeve, the cold air painful against his wrist, and glanced at his watch. It was 7:33, and shit, and he wasn’t even where the street ended in a ‘T’ and the shortcut path through the woods to the Thorsen house began.

He picked up the pace.

Thorian Thorsen’s big blue Bronco was sitting in the Thorsen driveway, the engine running at idle, sending up billows of smoke and clouds into the air. A long orange extension cord led from the grill into an outlet on the side of the house; a long thin rope just a few feet shorter than the cord was tied to both the car-side plug and a thick stainless steel O-ring bolted to the house.

Running the car was profligate, by local standards. Of course, by local standards, when you accidentally cut your arm off with a piece of farm machinery you waited in the bathtub after calling 911, so that your blood wouldn’t unnecessarily stain the carpet.

Still, the engine block heater alone would have let the car warm up quickly, once started, although the main purpose of it was to make sure the damn thing would start in the cold—it was for necessity, not comfort. But that was Thorsen’s way: go for the luxury of a heated car, and damn the expense.

Torrie’s dad was certainly willing to suffer discomfort—Ian had been around for some of that, and knew about some more—but only if there was some real benefit to be gained from doing so. The notion of deliberately suffering to build character was foreign to him.

Ian had no argument with that philosophy. Life was full enough of pain and heartache and just plain ordinary discomfort to build more than enough character; there was no reason to go looking for it. Hell, if the only pain Ian ever again had to suffer was from doing his stretches before he worked out, that would be fine with him.

He chuckled. And this from somebody whose itchy feet were going to be taking him back through the Hidden Ways to Tir Na Nog sooner than later.

Do as I say, people, not as I do, he thought, and laughed at himself. It wasn’t just that he wanted to see Marta again—although he certainly did—or Bóinn, or even her, although that was true, as well. And he wanted to see Arnie Selmo, for that matter. It would be good to look into Arnie’s lined face again, and see if Freya’s influence had lightened the dark cloud that seemed to have taken up permanent residence behind his tired eyes.

But it wasn’t just the destination. It was, as Freya had suggested to him, the going.

Home wasn’t just a place that you came back to; home was a place you had to leave every now and then, if only for the coming back.

But when?

There was no rush, and the fact that there was no rush warmed him in a way that the cold couldn’t even begin to touch.

After all, he was home.

Ian stashed his bag in the back of the Bronco—it was unlocked, of course; who would steal your car?—then walked up the path from the driveway (which was as free of snow as though it had been blasted with fire) and clumped up the wooden stairs to the porch, opening the storm door so that he could get at the heavy oak door.

He knocked at the door, tentatively, with his gloved hands, to no response, then shrugged and pounded once on the oblong brass knocking plate in the doorpost.

Thrummmmm.

The whole house vibrated with the deep bass note.

Ian didn’t wait for an answer, he turned the knob and pushed the door open six inches or so.

“Hello the house,” he said, his voice just above a low whisper.

The knob slipped from his gloves as the door opened the rest of the way to reveal Doc Sherve, dressed in a plaid shirt and jeans that, together with his beard and the small knit cap covering the top of his head in a way that reminded Ian more of a yarmulke than anything else, somehow made him look more like an ancient lumberjack than a physician.

A steaming mug of coffee was in his right hand, and he grinned as he beckoned Ian inside. “Don’t just stand there. It’s cold out, in case you haven’t noticed. Come on in and get warm.”

This didn’t make much sense. Where was Doc’s car?

Sherve brought the mug up toward his mouth, then his face wrinkled up and he shook his head and held the mug out to Ian, just as Ian finished stripping off his gloves and dropping them on the air vent next to the door.

Hmmm … the ring was still on his finger; he slipped it off and put it back in his pocket. He could feel the warmth of it even through his thermals.

Ian stomped his feet a couple of times to clear his boots of snow, then wiped them carefully on the snow runner as he followed Doc toward the kitchen, sipping at the coffee as he did. It tasted better than coffee usually did in Hardwood: it was weak but hot, and at this time of year hot was far more important than strong.

Sit around outside on a cold day drinking strong coffee whenever you needed to warm up, and you would piss brown for the rest of the day and climb the walls with your fingernails all night.

Thorian Thorsen and his wife, Karin, were sitting at the breakfast table, drinking coffee. From the remnants of egg and scraps of bacon and pancakes on his plate, it was obvious that Thorsen had just finished polishing off his usual huge breakfast, while Karin toyed with a piece of coffee cake.

Thorsen was half-dressed for the cold, the ropy muscles of his chest bulging against the smooth tightness of his satin polypropylene undershirt. His light brown, almost blond, hair was damp and combed back against his head, and despite his genuine smile his expression looked vaguely threatening, and made Ian want to avoid looking at his wife.

Ian was probably just projecting. It was probably the squareness of Thorsen’s jaw, combined with the bend in a nose that should have been straight, and it was certainly in part the long white scar that ran down the right side of his face, white stitchmarks like legs on a centipede announcing that the wound had been sewn together by somebody a lot less dexterous than Doc Sherve.

“Good morning, Ian Silver Stone,” Thorsen said.

“Morning, Thorian.” Ian didn’t correct him. He’d gotten used to it, in Tir Na Nog, and, what the fuck, eh? That’s what Silverstein meant, after all.

Doc chuckled, as he always did. “That’s Ian. The nonstick surface.” That hadn’t been funny the first time, or the fifty-first.

It still wasn’t. At this point, it was about as funny as Arnie’s joke about the pope and his chauffeur, which everybody in town seemed to have to tell him at least once, and which he had to smile through as though he had never heard it before.

For this, at least, he didn’t have to smile. But if glares could raise boils, Doc’s face would have exploded with pus some decades before.

“Good morning, Ian,” Karin said, looking up, but not quite meeting his eyes.

He had avoided looking at her, afraid, as always, that he would gawk. She was quite literally old enough to be his mother, but Ian found nothing matronly about her. She smelled of some vaguely lemony perfume that should have been too young for her but wasn’t. God, she was lovely, even at this hour of the morning, dressed in a thick red terry cloth robe that set off the hint of black lace where it opened at the swell of her breasts.

Her blond, almost golden, hair was tied back in a high ponytail that left the back of her neck bare and made his fingers itch.

Not that he would ever try to scratch that itch. There probably were a few better ways to screw up his life in Hardwood than making a pass at Torrie’s mom, but he couldn’t think of any, not offhand, unless it was, say, pissing on the Sunday smorgasbord at the Dine-a-mite.

She still had trouble meeting his eyes. “Can I get you some breakfast?” she asked, as she always did.

Ian shook his head. “No, thanks,” he answered, as he always did. Breakfast might well be the most important meal of the day, but Ian had always found that it went down better after he had been up and around for an hour or two. “I’ve got a few Poptarts in my bag.”

“Poptarts.” Doc shook his head, disgusted. “Not exactly the breakfast of champions. Lousy nutrition.”

“Hey, check the package. They’re not as bad as you think.”

“Don’t confuse me with facts. I’m a doctor, and I know better than you.”

There was no answering that.

Ian sat down and sipped at the coffee. “So, what are you doing here at this absurd hour of the morning, Doc? I didn’t see your car.” The huge white Chevy Suburban that Doc used as a portable office—and, when necessary, an ambulance—would have been distinctive for the light bars on top, even if it didn’t have the word Ambulance backwards on the front, forward on the back, and five little deers with red x’s painted through them on the driver’s door.

And if there had been a problem with Hosea, surely the car would be here, and Doc Sherve wouldn’t be sitting around drinking coffee with the Thorsens.

Doc might as well have read his mind. “No, he’s fine. He is just sleeping in.”

Ian heard the soft footsteps in the hall outside the kitchen.

“That turns out not to be the case,” a low, slightly slurred voice said. “I am quite well, but I am not asleep.”

Ian turned in his chair. Hosea Lincoln—well, that was what he was called here—stood in the kitchen doorway, wearing an ancient herringbone robe over yellow silk pajamas and slippers that looked to be as old as the robe. The robe was belted tightly; he seemed unhealthily skinny that way, much more so than in his usual outfit of plaid shirt and overalls, which at least gave the illusion of some bulk.

His skin was the color of coffee au lait, but there was something exotic and strange-looking about his eyes, and the way he appeared to be freshly shaved, as always. If he had any trace of beard, Ian had never seen it.

“Good morning, Hosea,” Ian said.

“Ian Silverstein,” Hosea said, with a slight nod. “A good morning to you, as well.” He limped into the kitchen; his right hand, as usual, hung down by his side, the fingers curled into a loose and almost useless fist.

Karin started to get up, presumably to pour him a cup of coffee, but desisted at a slight gesture from his left hand. Hosea preferred doing for himself, when he could. Which was most of the time.

“And since you’re not here to see to my medical needs, Doctor,” he said, as he poured steaming coffee into a mug covered with big red letters that read She Who Must Be Obeyed, “may I ask why this home has been graced by your most welcome company this morning?”

Once, Ian would have found his phrasing awkward, but that was before he spoke Bersmal—and that was the exact construction he would have used in Bersmal—and before he had met Hosea or any of Torrie’s family.

“My snowmobile’s out back,” Doc said. “I had another middle-of-the-night.” He grinned. “A birth, for once.” Doc liked delivering babies.

Ian searched his memory. “Leslie Gisslequist, maybe?” It was a bit early, but…

Doc’s grin widened. “Very good. A cute little girl, and a full seven pounds despite being two, almost three weeks, early—nominal delivery, everything you could ask for, except for Ottar’s stupid comments about the placenta.” He raised his palm. “Don’t ask, or I’ll tell you.”

And the snowmobile? Ian tried to remember where the Gisslequist farm was. Somewhere to the northeast, diagonally outside of town. Somebody who knew what he was doing could probably get there by snowmobile, cutting across snowed-over fields, faster than a car could by the road, what with the roads covered in spots with black ice that forced a sane driver to approach any intersection at a crawl.

Still, to hear Doc talk, you’d think that being woken in the middle of the night for some medical emergency was an unusual event, but Martha said it was a rare week that went by without him being called out at least twice, and it was one of the reasons that his talk about retirement was probably getting serious.

Doc was in fine shape for a man his age, but he was a man his age, and he wouldn’t last forever.

Nothing did. Not even the universe.

Ian sighed.

Ian shook his head. Trying to take the long view had never been a workable strategy for him, and probably wouldn’t ever be. It just wouldn’t be the same, when the nearest physician was in an ER in Grand Forks.

“So why all the interest?” Doc asked. “Just curiosity? Or what?”

Curiosity? Sure. “Mainly, it’s a bad habit,” Ian said.

“Do tell.”

“I… try too hard to figure things out.”

“And that’s a bad habit?”

“Can you figure everything out, Doc?”

“Hey, I’m a doctor. Of course I can.”

Ian shrugged. If Doc didn’t want to give a serious answer, well, then Ian didn’t have to, either.

Sherve bit his lip. “Okay, fine. There’s a lot I can’t figure out, but I don’t let it bother me.”

“Good for you. I do. It’s more a compulsion than anything else.”

You try to outgrow it, but you never can.

What you grow up with is normal; it’s only later that it turns crazy on you. It was normal to have a father who would strike out at you with his words or his hand, and it was normal to try to figure out what you had done wrong that had made him do it, this time.

If only, you thought, if only you got all your ducks lined up in a row, if only you understood everything, and knew everything, then you could do everything right and this time he’d smile at you, he’d hug you, he’d like you.

But that was bullshit. Ian hadn’t gotten beaten for not cleaning his room (the books were out of order and the loose papers were shoved under his bed), although he hadn’t, and he didn’t get shoved down the stairs for dawdling on his way home from school, although he had. Those were the triggers, the excuses, not the reasons. You couldn’t stop it by figuring it all out and doing it all right, because it wasn’t about you, and it didn’t matter what you did.

The trouble was, he couldn’t stop trying to figure it all out, and when he wasn’t watching himself, that old superstition welled up, that old myth that only if he knew everything, if he understood everything, it would all be all right.

Hosea’s hand griped Ian’s shoulder. “Do not whip your own spirits,” he said in Bersmal—for privacy perhaps, although both the Thorsens spoke Bersmal as well as Ian did. “I beg your pardon, Doctor,” Hosea said, this time in English. “I told Ian to be easy on himself. There is a reason that they call it ‘abuse,’ you know.”

“Yeah.” Doc shrugged an apology. “It was a stupid question. Kathy Aarsted’s the same way.”

“Kathy Bjerke,” Ian said, correcting. “And it wasn’t Bob Aarsted who abused her.”

Doc grinned. “You can put money on that, kid. If you can find somebody fool enough to bet with you.”

Karin Thorsen still wouldn’t meet his eyes.

You know, he wanted to say, maybe it’s about time we put all that behind us.

The last time he had taken a Hidden Way to Tir Na Nog, it had been at her pressuring, and she had rushed him into going through in an attempt to preempt either her son’s or her husband’s having to walk the soil of Tir Na Nog once again.

“It’s okay, Karin,” he said, quietly, knowing what she was thinking about.

Thorsen’s face was as impassive as carved granite.

Hosea smiled, and Sherve nodded his agreement. “It worked out well enough, in the end.”

The fact that a gorgeous woman, even one in her early forties, could wrap a man just barely into his twenties around her little finger with no more than a chin quiver was hardly news.

Besides, Ian had a thing for gorgeous older women. One—particularly gorgeous—and remarkably older—woman, in particular.

How old was Freya? And how could you measure such a thing? What was the proper yardstick? Given that the Old Gods had retired to Tir Na Nog long ago, and simple years wouldn’t do. Was it eons? Legends? Ages?

Never mind.

The problem was here and now.

Ian’s hand dipped into his pocket, and his fingers closed around the warmth of the ring once more. He slipped it onto his thumb.

He concentrated, and thought, Really, Karin, it’s okay. I’m not mad, not any more. She had viewed him as more expendable than her husband and son, and she had quite cleverly manipulated Ian into a dangerous situation that could easily have gotten him killed. But Ian wasn’t angry at her. He was jealous of Torrie and Thorian, sure—nobody had ever been that devoted to Ian Silverstein—but he wasn’t angry.

It’s okay. All is forgiven, he thought, willing her to believe him. It was true. You were allowed to persuade your friends that you had forgiven them, if you had; it wasn’t wrong, it wasn’t an abuse of the ring.

The ring pulsed, painfully tightening and then releasing on his thumb in time with his heartbeat.

Hosea nodded in agreement.

Karin Thorsen sighed, and visibly relaxed, and cocked her head to one side. “You look far away.”

Hosea chuckled. “That he’s been.”

He sat down next to Ian, reached for a roll of lefse from the plate on the table, and took a tentative nibble. Nice—the usual way to eat the soft potato flatbread was to spread a thin layer of butter over it, sprinkle on a little sugar, and then roll it up, but Karin had substituted a generous portion of her summer raspberry preserves—and maybe a little lemon zest?—on the lefse before rolling it up and cutting it like sushi.

Hosea was capable of putting away more food than Ian would have thought possible to fit into that skinny frame, but he didn’t follow the local custom of a heavy breakfast any more than Ian did.

“That he will be again, I don’t doubt,” Hosea said. “The winter out on the plains here is an acquired taste.”

Was Ian’s restlessness that transparent?

Hosea nodded, answering the unasked question. Yes, it was that transparent. At least to him. But maybe not everybody else could see it.

“Be that as it may,” Thorian Thorsen said, rising to his feet, “for now, Ian Silverstein and I have a shift to take, and little enough time to get there.” He rose to his feet and took a last bite of toast, washing it down with a last swig from his coffee cup. “Come, Ian Silverstein.”

“You bet.”

There was an old tan-and-Bondo Ford LTD station wagon parked down the road that led to the small stand of trees surrounded on all sides by snowy fields, which was all that remained of what had been some sort of sacred place a few hundred or a few thousand years before. Off in the trees, a wisp of smoke worked its way through the gray branches, only to be caught and shattered in the light wind.

Thorian Thorsen eased the Bronco onto the hard-packed ground next to the Ford, leaving plenty of room for Ian to swing the door all the way open, which he did. The air in the Bronco had been wonderfully warm; the outside air hit Ian with a cold slap.

You know it’s cold when you take a sniff and your boogers freeze, Ian thought, adjusting the cuffs of his parka to nest over his gloves before he shouldered his bag and Giantkiller’s cue case and followed Thorsen down the path of squeaking snow and into the woods.

It was a short walk, and it was good to get out of the wind, even though the naked trees only broke it up a little. At minus-God-only-knows, even the lightest breeze sucks every bit of the heat right out of you, and any relief whatsoever is always welcome.

The area around the cairn had been cleared that fall, and a warming hut, built out of an old ice fishing house, had been brought in. One wall had been cut almost completely away and left open toward the fire, which was still burning on a circle of three flat stones just behind the dark hole in the snow, itself in front of the old stone cairn that dated back to God-knows-when.

It wasn’t Lakota—Jeff Bjerke’s mother was a quarter Lakota, and she had talked to some tribal elders down in Pipestone and Rosebud—and the history of this part of the world before the Lakota was kind of sketchy. The various Plains Indian tribes had been too busy trying to scratch a living out of the forest and plains between making war on each other to take copious notes.

Or maybe it was just that they were considerate of future archaeologists?

Mmmm, probably not.

There was something about a fire that was even more warming than the temperature, which was just as well, given the temperature. Fire had melted down through the snow, and the snow had turned to water, trickling down into the hole. It was easy to ignore the hole in front of the fire, and in fact, it took some work to look at it for the first time.

Ian wondered, again, how much water it would take to fill up the hole.

Was it even possible?

Probably not. The properties of the Hidden Ways were built into the very structure of the universe, and it wasn’t likely that men or Man could change them. It was hard enough to notice them.

Davy Larsen was already halfway out of the warming house, a Garand rifle cradled in his arms, the muzzle carefully pointed in a neutral direction, the butt of a .45 semi-auto sticking out of his open parka.

Ian didn’t know much about guns, and wasn’t much interested in them. They didn’t have any, well, life to them, not the way a sword did.

And, besides, Hosea had said that they wouldn’t work in Tir Na Nog. No, that wasn’t quite it—he’d said they wouldn’t work, or would work too well. Ian didn’t particularly like the idea of confronting a Köld with a gun that would either blow up in his hand or only make clicking sounds. Come to think of it, he didn’t particularly like the idea of confronting a Köld, not if there was another good option.

“Morning, Ian, Thorian,” Davy said as he limped toward them, his words turning into a yawn.

“David.” Thorsen nodded.

“Hosea and Karin well?” he asked, politely, although there was just a hint of emphasis on Hosea’s name.

“He’s doing just fine,” Ian said. “Haven’t seen a seizure all winter, and he’s down to his old doses of the anticonvulsants, Doc says.”

“Well, that’s good.” Davy grinned as he held out the rifle to Thorsen. “Wouldn’t want him addicted,” he said. “Here. Have a rifle.”

Thorian Thorsen accepted the Garand and yanked the bolt open, catching the ejected round with a surprisingly quick movement of his right hand, which Ian had never seen anybody else dare to try, much less pull off in such a casual, matter-of-fact manner.

His gloved hand thumbed it back into place, but not before Ian noted that the bullet was silver.

As well it should have been. One of the manufacturers made bullets called Silvertips, but these weren’t them. These were cast from jeweler’s silver—the silver carefully mixed with old typesetting lead to give the bullet more heft and make it expand better in either human or nonhuman flesh—then formed, swaged, and loaded in the Thorsens’ basement with that funny-looking machine that reminded Ian of a blender with a thyroid condition.

Any bullet would hurt a Son of Fenris, at least for a few moments, but it took more than lead to put one down dead. It could be done, mind; the skeletons of six Fenrir lay buried in a field not too far from here as proof that that could be done, that they could be killed.

Giantkiller could do it, too; Hosea had tempered the edge in his own blood.

Ian set the cue case down on the crude table, opened it, and brought out Giantkiller in its scabbard. The new bell guard that Hosea had fitted to it was too shiny; maybe he should take some steel wool to it and blur the surface. His sword, like all the blades that Hosea had made for them, had been tempered in the blood of an Old One, and that gave it a certain authority. Magic? Not quite. But close enough—Giantkiller had slain a Köld and Ian himself had killed a fire giant with its hilt in his hand, and it was perfectly capable of doing in a Son, if it was necessary.

As it might be. This exit from the Hidden Ways had remained open at least since the Night of the Sons, and showed no sign of closing.

Could it be closed?

Even Hosea couldn’t say.

And if it was closed, did that make them safe? Or was there another exit, another adit, perhaps a thousand yards or a thousand miles away, that would open instead? You couldn’t fill it up, you couldn’t close it. Not so you’d be sure it stayed closed.

But you could watch it, and the men of Hardwood took their turns on watch.

Ian shrugged. What else could they do? Announce to the whole fucking world that there was a Hidden Way in a small clearing in a stand of trees surrounded by cornfields in eastern North Dakota?

What if somebody believed them? What if word of the Night of the Sons got out? Werewolves, attacking a North Dakota town, killing two people and injuring more?

Look what one silly little story had done to Roswell, New Mexico.

And this would be far worse, because it was true.

It isn’t only evil that hates the light. So does privacy. So does normality.

So does life, at least as lived in Hardwood.

Hardwood could become famous, and while the Hidden Way would conceal itself from those who didn’t know what they were looking for, life here would wither and die in the light of the flashbulbs of the National Enquirer.

That sort of publicity would be the end of life in this little town, and this little town suited its people just fine, thank you, and if keeping yet another secret would protect that life and that town and those people, then Hardwood could watch over the Hidden Way until the end of time.

It was boring, mainly, is what it was, but of all ways you could suffer in the world, boredom was Ian’s absolute favorite. You could let your mind wander when you were bored, and while he preferred to keep busy, that was better than some things.

If only it wasn’t so damn cold.

If only—

He heard a distant whimper, and was on his feet even before Thorsen was.

Guns were foreign to him, but at least a gun stood a chance of stopping a Son before it came close enough that he could feel its breath on him, so as he tore off his gloves to draw Giantkiller, he grabbed the pistol out of his pocket, as well.

The sound came again, and if his ears weren’t playing tricks on him, it was coming from the direction of the fire, from the exit, from the Hidden Way.

Finger off the trigger until you have a target, he reminded himself, hoping that his hand was trembling more from the cold than from fear.

But shit, he’d been frightened before, and he’d be frightened again. It didn’t matter how you felt, as long as you did the right thing.

“I’m to your right, Ian Silverstein,” Thorsen’s voice said in a rasp. “Careful, now.”

A thick, hairy hand reached up from inside the hole and grasped the edge of it, followed immediately by another, and for just a moment, a shock of black hair, and then a heavy eye ridge over two wide eyes peeked out.

And then, with a sound that was more a groan of pain than a grunt of effort, the fingers slipped and disappeared back down the hole.

Later, he wasn’t sure that his claim that he had thought it through was accurate.

It was more reflex than reason that had him drop the gun to one side and run for the hole, leaping down it without so much as a moment’s hesitation.

It was probably stupid, but he did have Giantkiller in his right hand, and as he landed on the hard ground at the bottom of the hole, he broke his fall as best he could with a roll like a skydiver’s.

Pain tore through his left shoulder in a horrid red wave that pulled a scream from his lips but didn’t loosen his grip on his sword.

He slid on the icy ground and into—

—and into the Hidden Way, and the curious silence that had no ring of tinnitus in it, the lack of cold that had no warmth, the absence of pressure that gave no release.

—peace. And silence. And an absence not only of pain but also of feeling.

Ian stood, surrounded by the gray light that seemed centered on him, vanishing off in the distance of the tunnel.

He wasn’t cold anymore. Nor tired, nor hungry, nor full, nor much of anything. Not even in pain. His ankles, his hip, no matter how well he’d broken his fall—

But even his shoulder didn’t hurt. He worked his left arm. It didn’t seem to want to move easily, but there was no pain at all.

He remembered banging his head against the hard ice at some point, but that didn’t hurt either, and even though his probing fingers found a bump, and came away tipped with red blood, there was no feeling of wetness of blood running down the side of his neck because there wasn’t blood running down the side of his neck.

There was a timelessness, a feelinglessness that came with the Hidden Ways, and while he should have been expecting it, each time it had come as a dull surprise, and this time was no different.

It wasn’t a bright shock, not reassuring or even frightening—in some ways that would have been better: that would have meant he was feeling something—but just a surprise, just different.

He was breathing—but hot heavily, not panting, not gasping, just breathing in and out—but he had the strong sensation that he could just stop and it would make no difference at all.

The body lying on the floor of the tunnel wasn’t breathing. It was a short, thick man, wearing rags that looked like they had once been a tunic of sorts, belted only with a length of tattered rope.

Or not a man. The forehead was too low, and sloped, and the hair was thicker on his arms and legs than Ian had ever seen on a human. He had been badly hurt. A gash on his right thigh leered wide and red, and another on his ribs revealed white bone.

He wasn’t bleeding, not anymore. The dead don’t bleed.

Ian nodded. It was a vestri, of course. What Ian would once have called a Neanderthal, perhaps; what the legends had called a dwarf.

Ian should have felt something about it lying there dead, but he didn’t. The Hidden Way robbed him of feelings in much the same way that it robbed him of feeling. Intellectually, he knew he should look around for danger, for some sign of whatever it was that had killed the dwarf, but the thought had no emotional weight to it.

Still, he looked down the tunnel as far as he could see. Nothing. Just grayness, vanishing off into darker grayness, eventually becoming black.

No. there was no feeling of danger here, and that was only in part because feeling itself was damped.

He turned back. Beyond the body of the dwarf, the grayness led out to a snowy patch, where traces of light filtered down onto the ice that was marked with the red of fresh blood. That was reality, and home, and solidity; the other way would take him, once again, to Tir Na Nog.

He would feel again, no matter where he came out.

And that would be a good thing. There were times when he could only prefer numbness, but death was the ultimate numbness, and he didn’t want to die.

In a distant, passionless way, part of him wanted to follow the Hidden Way, to Tir Na Nog, to Marta—and to her—and deep inside the numbness that lay over his feelings like a sodden blanket he thought that maybe that was, after all, the right thing to do: to heave the dwarf to his shoulder and carry it back to Tir Na Nog where its bones would lie with those of Vestri and his children.

Now that was a fit place for a Son of Vestri to lie in death; not deep beneath the almost impossibly black soil of a cornfield in North Dakota.

But Ian wasn’t prepared for a trip to Tir Na Nog. And it wasn’t just the lack of supplies and people waiting for him back in Hardwood. Those were details that could be handled, one way or another. He wasn’t prepared emotionally for it.

But why not? There were no emotions here; he could just go, and who would say he was wrong?

But, no: No. The gray dullness was not the right place to be making any sort of decision at all. Important decisions shouldn’t be made by a feeling-numbed mind, trapped in a gray timelessness that allowed only dry intellect. It was wrong to do such things when your mind was dulled by alcohol, or by the Hidden Ways.

It was illogical to rely solely on logic. Important decisions needed to be made with both intellect and emotion, with the heart and balls and the brain, with your mind and with your guts, not divorced from a human reality that was feeling as much as it was thought.

But he couldn’t just leave the dead dwarf lying here, caught in the interstices between worlds. And if he wasn’t going to take it to Tir Na Nog, then cold gray logic dictated that he would have to take it back with him.

There was no fourth choice, after all, and to not decide was a decision.

His parka was in the way, so he stripped it off and dropped it to one side, unsurprised that he was neither cold with it off nor sweating with it on.

But removing it let him slide Giantkiller through his belt, which he did, and he stooped to pick up the vestri.

It was limp in death, and that should have made it hard to lift, although not impossible; the advanced first aid class he had taken some years ago had taught him how to get a limp body up into a fireman’s carry.

But it just wasn’t all that hard: maybe the vestri was lighter than he looked, but it was only the matter of a few moments before he was able to get the little man’s limp body up to his right shoulder, balanced properly.

And, with one last look that would have been a longing one if the Hidden Way permitted such a feeling, he walked back toward the ice and—

—groaned in pain at the blazing agony in his left shoulder. He would have dropped the dwarf’s body, but he staggered up against the wall of the hole, bracing the body there, his feet finding purchase somehow or other.

“Ian!” Thorian Thorsen’s broad face leaned out over the edge of the hole, impossibly high, impossibly far away.

Ian was about to let the body drop when it moved against his shoulder.

The dwarf wasn’t dead; it was just unconscious, and the gray unchangingness of the Hidden Way had hidden that.

Something warm ran down Ian’s leg.

Shit. Its wounds were bleeding. No, his wounds were bleeding.

His jaw clenched tightly to keep any groan or scream from escaping, Ian braced himself hard against the wall and ignored the way that every movement of his left shoulder made him want to scream as he pulled Giantkiller from his belt and lowered the dwarf, as gently as he could, to the ground.

He glanced up. Thorsen was gone. All his effort to avoid whimpering had been for nothing.

Well, that was reassuring, if not particularly surprising. When it all went to hell around you, Thorian Thorsen could be counted on to do something constructive, if not necessarily the best thing.

Ian took a deep breath, regretting it as the cold dry air triggered a fit of coughing.

Okay, first thing was the airway, and with the dwarf’s wide mouth sagging open and the vapor from its breath in the air, he knew it could breathe.

Second thing was to stop the bleeding.

He had to stop the goddamn bleeding. Warm blood still seeped from the thigh wound, steam rising and vanishing in the cold air. He grabbed at the edges of the wound and tried to squeeze them together, but the thick, hairy skin was slippery with blood and dirt, and his frozen fingers couldn’t get any purchase around the dwarf’s broad thigh.

He was disgusted with himself almost to the point of nausea at how good the warm blood felt on his numbing fingers. But, shit, it did.

Ian stripped off his outer shirt, trying as hard as he could to ignore the way the movement of his left shoulder brought sparks to his brain and tears to his eyes, and he wrapped the shirt about the wound, tying the arms of the shirt together as tightly as he could.

That slowed the flow of the warm blood but didn’t stop it. But maybe that was enough until they could get him to a doctor, to Doc Sherve.

Where the fuck was Thorsen, though? What was he doing? It had been …

… it had only been a few seconds since Ian had emerged with the dwarf, and whatever he was doing would take more than just a few seconds—

The roar of a powerful V-8 and the smashing of brush cut through the sound of his own ragged, painful breathing.

—although maybe not much more.

Thorsen was back at the hole, in his hands what looked at first glance like a surfboard.

He lowered it on a rope. It was a board with holes for grips around the edges, but it looked like some strange bondage device, more than anything else, what with the Velcro straps on its side.

“Strap him on tightly, Ian Silverstein, then keep the board from turning over as I pull him up.”