Sir Henry Merrivale (better known to the public, and to his co-workers of the Military Intelligence Department as "H.M.") had disappeared. Two of his young friends were to be married the following day. Then a telegram arrived: MEET ME IMPERIAL HOTEL TORQUAY IMMEDIATELY EXPRESS LEAVES PADDINGTON 3:30 URGENT MERRIVALE.

At once everyone was precipitated into the Punch and Judy Murders… Hours later, the prospective bridegroom, now a fugitive from justice, and dressed in an unlawfully appropriated policeman's uniform, stood at the open door of a small library, confronted with a corpse. He was wondering how he could escape from the house before the bona fide police arrived…

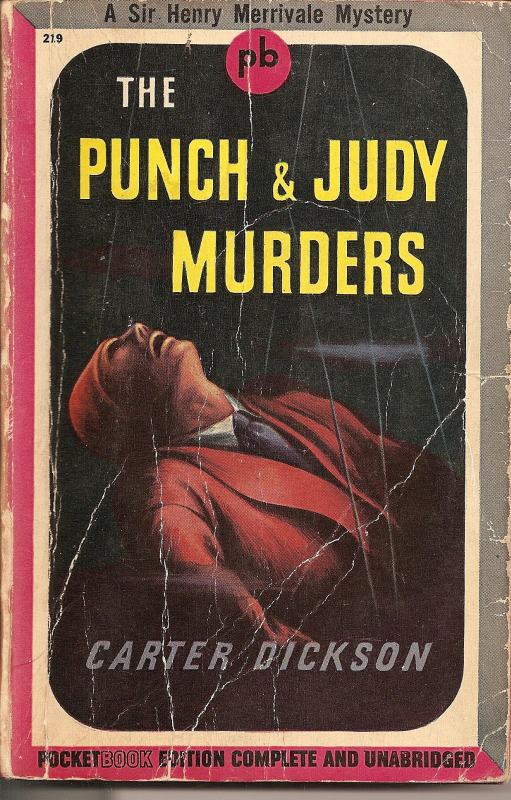

John Dickson Carr

Writing as

Carter Dickson

The Punch and Judy Murders

CHAPTER ONE

The Bridegroom Sets Out On His Travels

Handed in 1 P.M., Monday, June 15th:

KENWOOD BLAKE, EDWARDIAN HOUSE, BURY STREET, LONDON, S.W.I.

MEET ME IMPERIAL HOTEL TORQUAY IMMEDIATELY EXPRESS LEAVES PADDINGTON 3.30 URGENT. MERRIVALE.

Handed in 1.35 P.M.:

SIR HENRY MERRIVALE, IMPERIAL HOTEL, TORQUAY, DEVON.

ARE YOU CRAZY AM TO BE MARRIED TOMORROW MORNING IN CASE YOU'VE FORGOTTEN ALSO URGENT. BLAKE.

The next document, at 2.10, showed a broader epistolatory style. It had evidently been telephoned white-hot by the old man, without regard for economy or coherence:

DON'T YOU GIVE ME ANY OF YOUR SAUCE CURSE YOU YOU BE ON THAT TRAIN ILL SEE YOU GET BACK IN TIME FOR THE SLAUGHTER I AM TO BE THERE MYSELF AINT I BUT THIS IS IMPORTANT YOU BE ON THAT TRAIN ABSOLUTE BURNING IMPERATIVE THAT YOU BE BUTLER.

Any philosophical soul, on the eve of his wedding, must suspect that some damned thing or other will go wrong. It is bound to. That is the cussedness of all human affairs. And I had learned that it was particularly the case in anything which concerned Evelyn Cheyne and myself. Thus, on that hot, murky June afternoon while I sat in my flat taking sustenance out of a tall glass and studying this telegram, it appeared that — for some reason unknown, less than twenty-four hours before the wedding — I was supposed to go to Torquay and be a butler.

It was just a little over a year after that wild business at the Chateau de I'Ile in France, which has since become known as the Unicorn Murders. Evelyn Cheyne and I were going to make a match of it: the only wonder may be why we had waited so long. It had been no fault of ours. The reason was the same reason why both of us were uneasy about this wedding — Evelyn's parents.

To say that they were holy terrors would be unjust, and conveys a wrong impression. Major-General Sir Edward Kent-Fortescue Cheyne was a good sort, and on my side; Lady Cheyne, though inclined to be weepy, was as much as could be asked for. But imagine what you think both would be like from their names: that's it. When we broke the news to them, Lady Cheyne wept a little and the General said gruffly that he hoped he could entrust his daughter's happiness to my keeping. Under these omens they were sticklers for everything going according to form. The General had arranged a formal wedding, which was something of a cross between the Aldershot Tattoo and the Burial of Sir John Moore. I need not add that it gave both Evelyn and myself the hump. He was even bringing over a great old school-pal of his from Canada, now become a notorious clergyman or a bishop or some such thing to perform the ceremony. Consequently, I did not like to think what would happen if I failed to show up on time at precisely eleven-thirty A.M. On Tuesday morning.

But here was H.M.'s telegram; and it looked like trouble.

I did what I should have done in the first place: I put through a trunk call to Torquay. But H.M. was not at the hotel, and had left no message. Then I rang up Evelyn. The wench, usually so full of the devil, was in nearly as low spirits as myself. She spoke in a small worried voice.

"Ken, it looks like trouble."

"It does."

"But Ken, are you going? I mean, the old man's done a tremendous lot for us, and I don't see how you can let him down if he asks you to go. Do you think it's-?"

She meant: "Do. you think it's Military Intelligence Department work?" H.M., who controls that network, requires a powerful stimulus to push his feet off the desk at the War Office and get him to move anywhere under his own steam. Since even the heavy labour of moving from his office to his home always produces an epic of inspired grousing, his presence in Torquay was important. All the same, I have no longer any official connection with his Department; and Evelyn, who once had a hand in it as well, had given in her resignation over a month before.

"So why me?" I said, "when he's got three dozen people with more brains ready to be called up, and particularly at a time like this? I should have to call off that dinner to-night for one thing, and that would put everybody's back up. Besides, I feel it in my bones some damned thing or other is bound to happen. Every time H.M. is ill-advised enough to stray out of his office, and drags me along with him, it always ends up in my being chased by the police."

"But are you going?"

"Wench, I've got to go. The last time, you remember, I mixed myself up in an affair where I had no business; and H.M. pulled me out… "

There was a pause, during which Evelyn appeared to be dreaming. Then the telephone emitted what seemed to be a faint chortle of pleasure. "I say, but didn't we have a grand time, though?" she crowed. "Look here, Ken: I'll tell you what: let me go along with you. Then, if we don't get back in time, we'll both be in the soup and we can get married at a registry office, which is what I want to do, anyway."

"NO! Your old man-"

"Yes, I suppose you're right," she admitted with suspicious meekness. "Anyway; whatever happens, we've simply got to have the plush-horse service at St. Margaret's, or I should never hear the last of it. But what is H.M. up to, do you think? Did you know he was in Torquay? Did anybody know he was in Torquay?"

I reflected. "Yes, I knew he was out of town. Nobody seems to know his whereabouts. Last Saturday there was an American named Stone here looking for him. Stone went to the War Office, but they either couldn't or wouldn't tell anything. Then he dug up Masters at the Yard; Masters knew nothing, and passed him on to me."

"Stone?" repeated Evelyn. "Who's Stone? Do you know what he wanted with H.M.?"

"No. He looked like a private detective. But I was too much taken up with other matters to be curious. Here: are you sure you won't mind if-?’

"Darling," said Evelyn, "you go ahead, and I'd only love to go with you. But for heaven's sake try, try to get back in time for the wedding! You know what'll happen if you don't."

I knew: very probably I should have to take her father's horse-whip away from him and sit on his head on the steps of the Atheneum. So I rang off, after farewells in which Evelyn almost tearfully implored me to take care, and began 'phoning in earnest to cancel arrangements for that night. It was a mess all the way round; and Sandy Armitage, who was to be my best man, was not pleased. It was twenty minutes past three before I finally piled into a cab-without taking so much as a tooth-brush-and reached Paddington just in time to swing aboard the train when the whistle blew. London streets looked yellow and sticky in the heat-haze, and the train-shed was worse. I sat back in the corner of an empty compartment to cool off and consider.

The mention of Stone's visit brought back to mind another puzzling thing. Stone had charged into my flat demanding to know where H.M. was, and acting in a mysterious way; but he seemed very well informed. At least the War Office seemed to have given him what help it could, so he doubtless had tolerably high credentials. Yet one thing stood out of Stone's guarded conversation: H.M., he said, had been behaving queerly. Now, of course, H.M.'s conduct at its mildest can seldom be described as homely or commonplace, and I knew that this must have reference to some current office joke which Stone (who had never met him) would not understand. Mr. Johnson Stone was a stocky, grey-haired man, with good-natured eyes behind a rimless pince-nez, and a preternaturally solemn jaw. Searching all over London after H.M. had put him into a great fume.

"They tell me," he had said, looking at me sideways, "that your Chief is a mighty queer sort of fellow. They say he's now got into the habit of going around in disguise.

This was startling even for H.M., and I became certain it referred to some joke. I gave Stone my solemn oath that the head of the Military Intelligence Department (or anybody else under him) was seldom known to go about in disguise. But somebody had evidently made a powerful impression on Stone — I could darkly see the hand of Lollypop, H.M.'s blonde secretary — and Stone went out muttering that it was a very fishy business; with which I was inclined to agree. In other words, what was the old blighter up to?

The train was due in Torquay at 7.38. It was a hot and gritty ride, with every click of the wheels diminishing the time when I must be back in London. But, when we came out into the deep trees and red soil of Devon, running for miles beside the sea, I began to feel somewhat soothed. I changed at Moreton Abbot, and just on time we pulled into Torquay station on a clear evening with the breath of the sea on the air. Outside, when I was looking round for a station wagon for the Imperial Hotel, a long blue Lanchester drew up at the kerb. A chauffeur drooped at the wheel; and in the tonneau, his hands folded over his stomach, glared H. M. But I almost failed to recognize him, and the reason was his hat.

He wore a fresh-linen Panama hat with a blue-on-white band, and its brim was turned down all around. There was the broad figure, weighing fourteen stone; the broad nose with spectacles pulled down on it; the corners of the mouth turned down, and an expression of extraordinary malevolence on the wooden face. But nobody in twenty Years, I think, had ever seen him without the top-hat which he said was a present from Queen Victoria. The effect of that festive Panama, its down-turned brim giving it the look of a bowl, and the malignant face blinking under it as he sat motionless, with his hands folded on his stomach, was not one that could be seen with gravity. I began to see the explanation of his disguise.

"Take it off," I said out of the corner of my mouth. "We know you."

H.M. was suddenly galvanized. He turned with slow and terrifying wrath. "You too?" he said. "Burn me, ain't there any loyalty in this world? Ain't there any loyalty in this world: that's what I want to know? If I hear just one more remark about disguises and false whiskers and What's wrong with this hat? Hey? What's wrong with it? It's a jolly good hat." Laboriously he removed it, revealing a bald head shining in the evening sun; he blinked at the hat with defiant respect, turned it round in his fingers, and replaced it. His sense of grievance rose querulously. "Ain't I got a right to be cool if I want to? Ain't I got a right-"

"We won't discuss that now," I said. "Speaking of loyalty: I'm here. The wedding is at eleven-thirty tomorrow morning, so let's get on with whatever business there is."

"Well… now," said H.M., rubbing his chin rather guiltily. He covered it up with an outburst about there being no reason why people should get married anyway; but at length he grudgingly admitted that both of us could be back in London on time. Then he waved a flipper at the chauffeur. "Buzz off, Charley. Mr. Butler will drive us back. Your name, Ken, is Robert T. Butler. That mean anything to you, hey?"

And then occurred revelation. "About 1917," I said, with the past opening up. "September or October. Hogenauer — "

"Good," grunted H.M. I climbed into the driver's seat, and H.M., with many curses, climbed beside me. He directed me out of town by the bus route towards Babbacombe; but I thought that under his grousing he seemed very worried, especially since he went to business at once. "It's more'n fifteen years ago, and neither of us is gettin' any younger, but I hoped you'd remember….

"You played the part of one Robert T. Butler, of New York," he grunted, with a curious obstinate look about him. "You were supposed to be an outlawed American sidin' violently with Germany in the Late Quarrel, and rather tied up with their secret service. Your business was to investigate Paul Hogenauer. Hogenauer had been givin' us a lot of headaches. The question was whether he was just what he pretended to be, a good British subject, the son of a naturalized German father and English mother: or whether he was tangled up with the feller they called L. in a bit of work that would have got him shot at the Tower. Humph. You remember now?"

"I don't remember this `L' whoever he is," I said; "but Hogenauer — yes, very well. I also remember that he got a clean bill of health. He wasn't a spy. He was just what he pretended to be."

H.M. nodded. But be put his hands to his temples under the brim of the Panama hat, and rubbed them slowly, with the same obstinate fishy look.

"Uh-huh. Yes. Now consider Paul Hogenauer a minute. Ken, that fellow was and is a genius of sorts…. When you knew him he was about thirty-five. At thirty-five he'd been offered a chair in physiology at Breslau. Then he got to tinkerin' with psychology as well; he'd got a new hobby each week. He was a chess wizard, and no bad hand at cryptograms or ciphers. To add to the staggerin', total, he was a chemist. Finally, there wasn't much about engraving he didn't know, or inks, or dyes — which was one reason why Whitehall wanted to keep on the good side of him if he wasn't a German spy. With all that, dye see, he was a simple-minded soul, with a sort of foggy honesty; or wasn't he? Burn me, son, that's just what I want to know! That's what bothers me."

H.M. scowled malignantly. I still did not see how this concerned me, and said so.

"He got a clean bill of health: sure. And I'm pretty sure there was no hanky-panky about it. But," argued H.M., "immediately after that, what does he do? In October, '17, he leaves the country for Switzerland. Well, we don't stop him. And then he turns up in Germany. And then about a month

later we get a nice, polite letter, as long as your arm and as muddled as your head, explainin' what he's going to do and the reasons for it. Half his heart (that's the words he used) is in Germany. He's goin' over to Germany. He's goin' into the little office on the Koenigstrasse where they move pins and decode letters and try to nail Allied spies. It's his conscience, he says. Now, I'll stake my last farthing he never had a suspicion he was under observation in England, and also that he never did any dirty work over here. But why all this bleedin' honesty? What made his heart suddenly flutter for Germany after three years of war? The whole point is, is he to be trusted?"

I tried to call back recollections from some time ago, and pictured a small, mild, spindly man, already going bald, with a shiny black coat and a tie like a bootlace. Like most ethers, I had been as callow as soap in those days; I remember having been rather contemptuous of him; but since, once or twice, I have wondered whether Paul Hogenauer might not have been discreetly smiling.

"It's interesting enough," I admitted, "but still I want to know where I come in. I suppose Hogenauer's in England now?"

"Oh, yes, he's in England," growled H.M. "He's been here for eight or nine months. Ken, there's some great big ugly black business, goin' on, and I can't put my finger just on it. It's all wrong. Hogenauer is mixed up in it: I don't mean that he's doin' the dirty work, but he knows who is. Or else — Well, Charters and I tumbled smack into the middle of it."

I whistled. "It sounds like a gathering of the old clan. You mean Colonel Charters?"

"Uh-huh. He didn't drop into it officially, of course; he hasn't been connected with the Department for a long time. But he's now Chief Constable of the county, and Hogenauer ran into him, and he sent a line to the old man. We're goin' to Charters's house now."

He nodded ahead. We had left the main road between Torquay and Babbacombe, and turned into a red-soil road which curved up over the great headlands beside the sea. Ahead and to the right, I could see the cliffs of Babbacombe tumble down sheer to the water, and to a strip of pebbled beach laced with a froth of surf far below. The sea was grey-blue, the beach a dazzling white, the cliffs patched with dark green, all in colours as brilliant as a picture post-card. Alone at the top of the headland in front of us, H.M.'s gesture indicated a long, low bungalow built in the South African style, with a veranda around all four sides. There was no other house near it except a smaller, more sedate house in red brick, about a hundred yards away, and separated from the bungalow by a tennis court. On this more prim house the fading sunlight caught a glitter from a doctor's brass nameplate beside the door. We were making for the door of the bungalow, which was shaded with laurels.

"And the next point," said H.M., staring ahead, "is not only whether Hogenauer's to be trusted, but whether he's sane. I told you he was pretty restless about. movin' from one hobby to another. Well, son, he's got an awful queer hobby now. It's ghosts."

"You mean spiritualism?"

"No, I don't," said H.M. "I mean he claims to have a scientific theory which will explain, on physical grounds, every ghost that ever walked and every banshee that ever wailed. There's somethin', also, about being able to transfer himself through the air, unseen, like Albertus Magnus: or some such scientific fairy-tale. Ken, that feller's either a lunatic or a quack or a genius. And you've got to find out which."

CHAPTER TWO

The Inverted Flower-pot

I looked round at H.M., who was quite serious. He had turned to regard me with his head over his shoulder, the corners of his mouth drawn down and his face as wooden as ever; but with his eyes half shut in that sardonic, fishy look which I could not interpret. Then we pulled up at the veranda of the bungalow. A blue Hillman touring-car stood in the drive.

Colonel and Mrs. Charters were waiting for us on the porch. Charters I had not seen since the old days, when he had been H.M.'s right-hand man and very nearly his rival. But the years had not treated him, kindly in any way. He still kept his leanness, his stiff back, his clipped and courteous manner; yet he was an old man, and the expression round his eyes was one of worry and fretfulness — as though over

trifles. He looked as though he had missed the good things, and knew it. His dull-grey hair was close-cropped round the long head, his dull-grey eyes were kindly but tired, and I suspected that he had a set of false teeth to annoy him. The mufti smartness of his clothes was not so precise as I remembered it, but I instinctively addressed him as "sir," exactly as though it were the old days. Mrs. Charters, a good-natured dumpling of a woman in a print dress, bustled to make us welcome.

"I know it's the devil, Blake," Charters said, "to drag a man away on the evening before his wedding. Swear if you must, but listen: Merrivale and I decided you were the best one to help us." His bony grip was genial, even if his voice sounded fretful. "Come back here."

He led us to the wide veranda at the rear, overlooking a faint-gleaming sea on which there were now shadows. A cool breeze ruffled through it. There were comfortable wicker-chairs, and bottles and a bowl of ice on the table. Charters picked up a cube of ice and dropped it, with a flat clink as though he were reflecting, into a tall glass. Then he looked out over the veranda-rail, down the height of the cliffs to where, far off, the beach was dotted with the heads of bathers in the surf.

"It's very peaceful down there," he said. "I only hope to God it remains so. This is a quiet corner of the world. I didn't want this business cropping up. I thought, when we'd caught Willoughby the other week, that we had the most in excitement Devon could provide." He nodded towards a window, which evidently gave on his study, and at a tall iron safe just inside. I did not understand what he meant by Willoughby or by the glance at that safe, I only wish I had asked. Charters had turned irritable again. "That was ordinary crime, but this cursed business-!’ Did you tell him, Merrivale?"

"I said Hogenauer was here, that's all," grunted H.M.

"And," I put in, "that he was working on a machine or something to make himself invisible and carry him through the air. Look here, sir, you haven't brought me several hundred miles just to talk nonsense. What's it all about?"

Charters dropped another cube of ice into the glass. "It's about this," he said. "I didn't know Hogenauer was in England, much less living within a dozen miles of here, until about three months ago. When you came up here did you notice another house — little brick house-just over the way? Yes. There's a Dr.-Antrim living there: youngish, quite a good fellow, with a very pleasant wife. My wife took quite a fancy to her. We've struck up an acquaintance, and we've more or less run in and out of each other's houses. One evening Antrim came up here bursting with news. It appeared he had just met an old acquaintance of his — Antrim had studied in Germany — about whose scientific talents he was enthusiastic. Yes: it was Hogenauer.

"Antrim was very anxious for me to meet Hogenauer. But we never did. I didn't let on to Antrim that I knew him, and Hogenauer has kept a very tight-closed mouth about knowing me. After he heard I was here, he only came up to see Antrim once or twice, though Antrim is his doctor and Hogenauer doesn't seem to have been well. I immediately looked him up at the police station. He's registered at the alien's bureau, and since last autumn he's been living in a neat little suburban villa at Moreton Abbot, not far from here. Well, I put a man to watch him. Of course, I had nothing to go on…. "

Charters handed round some admirable gin-fizzes. A little of his old sharpness, his old doggedness, had come back when he began to outline his facts. He sat down on the veranda-rail, his arms folded and hands cradled under bony elbows.

"He's been leading an ordinary life: except for one thing. On every alternate day, between eight and nine in the evening and often until much later, he shuts himself up in his back parlour. The windows are closed up with shutters of the old-fashioned wooden kind. The man I had watching him — Sergeant Davis — tried to get close and see what was going on. One night he climbed over the garden wall, crawled up under the window, and tried to look through chinks in the shutter. And this is what he says: he says that the room was dark, but that it seemed to be very full of small, moving darts of light flickering round a thing like a flower-pot turned upside down."

H.M., who had been getting out his pipe, opened his eyes, shut them, and opened them again. His turned-down Panama hat gave his face the look of a malevolent urchin's. "Oh, love-a-duck," he said. "Look here, old son. This Sergeant Davis, is he-'

"He's absolutely reliable. You can talk to him for yourself."

"What about Hogenauer's household?"

"He keeps one manservant to do the cooking and cleaning. Or a series of them, rather. Two have already got the sack for being inquisitive. There's a new man there now."

"Any friends? Close friends, I mean?"

Charters tried to gnaw at his cropped moustache. "I was coming to that. As I say, I had my attention rather distracted by that Willoughby affair, which put me up to the eyes in work. But this much I can tell you. Hogenauer left Germany after, apparently, a quarrel with the government; and also apparently he didn't leave it with much money. Since he's been living at Moreton Abbot, he's had only one friend-in fact, outside Antrim the only man who's visited him at all. And this friend is Albert Keppel; he's dropped the `von.' "

"Uh-huh. The physicist," said H.M., making a vacant circle in the air with his pipe. "I heard him lecture. Pretty sound feller. And Keppel is a kind of exchange professor who's been lecturin' for a year at the University of Bristol. And Keppel lives in Bristol. And at Filton, in that same Bristol, is the biggest aeroplane works in England. And they're workin' double-shift, night and day, behind locked doors, on God-knows-what. Hey? Still…"

He made another circle in the air with his pipe.

"And still," I said, "I don't see what it has to do with me’

"Because L. is in England," replied Charters sharply. He got up from the rail, and began to pace the veranda. He seemed to be looking back over the past. "I dare say you didn't know L. Merrivale and I did — at least, we knew his name."

"But not the man?"

"But not the man," said Charters grimly, "or the woman. L. may be a man or a woman. There's always been a dispute about that. All we know is that L. was the cleverest limb of Satan that ever plagued the Counter-Espionage Service. My God, Merrivale, do you remember '15. The tanks? L. very nearly got away with that information, if we hadn't stopped the bolt-hole. You see, L. wasn't and isn't a German, so far as we know; yet he might be German or English or French. He's a kind of international broker for secrets, and he doesn't care particularly whom he serves so long as he's paid. He's out after the big secrets. He gets them, and he sells them to the highest bidder."

"But look here," I protested: "nearly twenty years after all the fuss, he must be a real Iron Man if he's still working. And surely you must have some clue- "

"We have," said Charters calmly. "Hogenauer has offered to tell us who L. is."

There was a pause. The light was darkening to faint purple along the water, and the cliffs threw long shadows. Inside the house I heard a clock strike the quarter-hour after eight. Charter's long face, with its high ascetic framework of bones, was now as puzzled as H.M.'s.

"It was a week ago to-night," Charters went on, considering each word, "and Hogenauer came here-alone. It was the first time I had seen him face to face since the old days when we had him under observation. We've got a small household: just my wife, my secretary, and the maid: but they were all out. There's an inspector of police named Daniels, who sometimes goes over reports with me in the evening, but he had just left. I was sitting there in my study," he pointed to the window of the room I had observed before, "at a table drawn near the window, with the lamp lighted. It was very warm, and the window was up. All of a sudden I looked up from my papers-and there was Hogenauer, standing outside the window looking in at me."

He paused, and looked at H.M. "Merrivale, it was dashed queer. You used to say I hadn't much imagination. Perhaps not; I don't know. I hadn't heard the man approach; I simply looked up, and there he was; or half of him over the sill of the window. I knew him in a second. He hadn't changed much, but he looked ill. He was as little and mild and sharp-featured as ever, but his skin looked like oiled paper over the bridge of his nose. I've seen people in a bout of malaria who had eyes just like his. He said, `Good evening,' and then — just as casual as be damned — he climbed over the sill of the window into the room, and took off his hat, and sat down opposite me. Then he said, `I want to sell you a secret for two thousand pounds."'

Charters looked satirically at both of us.

"Of course, I had to pretend I didn't know him, and what was he doing there, and how did he know me. He corrected me very mildly, and said: `I think you know me. I once wrote you a letter explaining why I was going to Germany, and why I could not reveal the dye-process on which I was working. In Berlin we knew all the men who worked against us in your bureau."'

"Bah!" snorted H.M., who was' evidently stung.

'Bluff" said Charters. "And yet I don't think it was. He might be mad, though: that was what occurred to me. The long and short of it was that he told me L. was in England, and offered to tell me who L. is, and where to find him, for two thousand pounds. I told him I was no longer in the service, and asked him why he didn't communicate with you. He said, very calmly, that to communicate with you — and to be known as having done it — would be as much as his life was worth. He said: `I want two thousand pounds, but I will not risk my life for it.' Then I asked him why he needed money so badly. He began to talk of his `invention,' or his `experiment'. Merrivale has told you as much of that as I know… and I began to think he was mad. What I can't describe is the supreme — what's the word I want? — the supreme quietness of the man, sitting with his hands folded on his hat, and his bald head, and his eyes as big and fixed as a stuffed cat's.

"Anyhow, Blake, I made a trip to London to see Merrivale next day. Hogenauer hadn't been lying; L. is believed to be in England now."

Charters stopped, and dusted the knees of his trousers like a man who wishes to get rid of the whole thing. His conscience appeared to be bothering him.

"Ho ho ho," chortled H.M., with a leer. "Charters has got it stuck in his throat; he can't go any farther; he can't tell you where you come in, Ken. But I will. You're goin' to do a spot of housebreaking."

I set down my empty glass, looked at H.M., and began to feel a trifle ill.

"Point's this," pursued H.M. obstinately, and pointed with a vast flipper. "If Hogenauer's on the level, he could get his two thousand quid. Oh, yes. We've made these little bargains before, though nobody ever whispers it to the police. I'd be willing to pay it out of my own pocket. But is be on the level? Son, there's something awful fishy about this whole business, and I smell the blood of an Englishman again. It's all wrong. There's somethin' rummy and devilish peepin' out of it, which we don't begin to understand. Therefore we got to begin to understand it. Therefore, you're goin' to bust into this beggar's house, and overhaul his papers if he's got any, and find out what the flickering lights mean when they whirl round the flower-pot. Got it?"

Charters cleared his throat. "Of course," he said, "I can't give you any official sanction.

"Exactly," I said, "so what if I'm caught? Damn it all, tomorrow I'm supposed to be married. Why don't you hire a professional burglar?"

"Because I couldn't protect a professional burglar," answered the Chief Constable rather snappishly, "and I can protect you. Besides, there will be no danger. Hogenauer is going to Bristol to-night, not later than by the eight o'clock train, and he won't be back until tomorrow. He was at Dr. Antrim's last night, and told Antrim that. As for the manservant, he's courting a girl in Torquay and won't be back until midnight at the earliest. You will have a couple of hours after dark — probably more-to make a thorough examination of an empty house." Then Charters grew uneasy, after the effervescence of the old days had subsided. "But it's damned irregular all the same," he grumbled. "I shouldn't blame you if you refused to go. Mind, Merrivale, this is your responsibility entirely. If anything should go wrong-"

I pointed out, with some heat, just whose responsibility it was. H.M. was soothing. "Looky here!" he added, with an air of inspiration, as though he were dangling a peppermint-stick in front of a child. He lumbered into the house and emerged with a small black satchel, rather like a doctor's medicine-case. From this he took a series of skeleton keys, or `twirlers' as we used to call them, a brace and bit, wedges, a forceps, and a glass-worker's diamond. Next came a clawshaped jemmy whose design was new to me, a small bottle of paraffin oil to use on the metal instruments, a pair of rubber gloves, and a very curious tiny bottle which glowed inside like a cluster of fireflies.

"The Compleat Burglar," observed H.M. with ghoulish relish. "Don't it fire your blood, Ken? This is a telescopic jemmy; finest thing made; a yard long extended, and it's got a powerful leverage. This bottle of phosphorus is much better than a flashlight. Flashlights have a habit of flyin' all over the place, and coppers see them through the window. This can't be seen, and there's enough light for any honest purpose. I say, Charters, we'd better put in some stickin'plaster for him in case he has to cut a pane out of a window. You take my advice, Ken, and try the scullery window first; that's the most vulnerable part of any house. You're wearin' a dark-blue suit, and that's all right…"

"Just a minute," I interposed. "What I want to know is, why the unnecessary camouflage? Instead of saying, `absolute burning imperative that you be butler,' why didn't you say burglar? What has my role as Robert Butler got to do with this?"

H.M. did not roar. He remained blinking steadily at me, turning over the jemmy in his hand.

"That's our second line of defence, son," he said, "in case anything goes wrong. I don't mean to minimize the risks. There's very, very nimble-minded people working against us, and the trouble is that we don't have a ghost of an idea what they're doin'. It's just possible they've laid some kind of trap. Out somewhere there're three people whose ideas or motives we don't know. First, there's Paul Hogenauer. Second, there's that apparently harmless professor of physics, Dr. Albert Keppel. Third, there's the elusive L. It may be that none of 'em has a dangerous purpose at all. Or, again, it's just possible that Hogenauer has laid some sort of trap for us — or whatever agent we send. It's just possible his goin' away to Bristol to-night is a blind. I don't say it's probable, but it's possible."

"And I may walk into this trap?"

H.M. grunted. "That's why I asked you to come here. There's plenty of smart lads who could do a neater job of jemmying a window or cavortin' on a drain-pipe, if that's all I wanted. But you met Hogenauer in the old days. You met him in the character of Robert Butler, a spy and a bitter enemy of England, and Hogenauer never forgets a face. So far as we know, he never knew any different about you. If by any chance this is a trap, you'll walk into it before you've done any damage. You can pretend to be an ally of his, you can pretend to be on his side — and you're the only one who can pretend that. You can get out of it before you're into it, if it is a trap. And you may be able to learn something."

"Or walk into a bullet," I said. "Hogenauer seems to know a whole lot about us. Has it occurred to you that he may know all about me as well, and that he knew about me in my `Butler role?"

"Uh-huh," said H.M., nodding rather vaguely. "Sure, Ken; it was the first thing I thought of. But somehow… I move in mysterious ways of cussedness. You may have noticed it. I got plans at the back of my head; I see a move and jump or two on funny gambits, as Charters can tell you; oh, yes. And somehow I don't think you're in as much danger as you might be. I know I seem to be askin' an awful lot of you, especially at a time like this; and you'd be quite right to tell me to go and jump in the bay. But will you trust the old man?"

"Right," I said. "Let's get on with it. When do I start?"

"Good," said Charters quietly. "You'd better have something to eat first. It won't be dark until close on ten o'clock, but you'd better start about nine and reconnoitre the neighbourhood. Sergeant Davis wrote down Hogenauer's address for me somewhere: I think it's `The Larches,' Valley Road, Moreton Abbot. The servant, as I told you, will be going to see a girl and you'll have a clear road. You'll take a car, of course, but I don't need to tell you to park it some distance away from the house. Take Merrivale's car: or mine if you prefer it, unless Serpos has got it out now…."

H.M. seemed mildly disturbed.

"This Serpos, now," he suggested. "That's your secretary, ain't it? Exceedingly limp feller I saw up here last night?"

Charters was sarcastic. "You always were a suspicious beggar, Merrivale. Sinister-sounding foreign name, eh, and the legend of the villainous secretary? Nonsense! Young Serpos is about as meek and mild as they make 'em. I knew his father quite well. Serpos is an Armenian: but educated in England, of course. He worked in a bank in London, but his health wasn't any too good, and I gave him easier work in a healthier climate. Rather amusing chap," Charters admitted grudgingly, "and an expert mimic when you get him started. He'd make money on the halls."

"It's a queer international stew all the same," muttered H.M. shaking his head. "And while we're on the subject, Charters, who's this Dr. Antrim?"

"No more foreigners. And," said the Chief Constable, "if you're looking for suspicious characters near at hand, I think you can safely forget it." He chuckled. "Antrim is a big Irishman. You'll like him. His wife is a dashed pretty girl: much too pretty to be a trained nurse, which I believe she was before they were married. She helps him with his work. Of course, the life of a country G.P. isn't very exciting, any more than the rest of our lives are…."

He stopped, rather guiltily, as we heard heavy footfalls clumping through the main hall of the house. H.M. swept up the kit of the Compleat Burglar, and had just snapped shut the catch of the little bag when a tall figure lumbered out on the veranda.

"I say, Charters-" the newcomer began excitedly, and stopped when he saw us. "Sorry," he added. "Didn't know you had visitors. Excuse me. Some other time."

I thought, correctly, that this must be Dr. Antrim. He was a lean, rather awkward young man with hair the colour of mahogany, some freckles, a long jaw, and a brown eye like a genial cow: but he conveyed, nevertheless, an impression of competence. His hands were quiet and strong if his man

ner was not. His dark clothes were neat to the point of primness, as though a woman had pulled at his tie and steadied all points like somebody putting up a tent, before he was allowed to go out. Evidently he had just come in from a round of calls, for there was the bulge of a stethoscope in his breast-pocket and he looked dusty. Also, something appeared to be worrying him badly. Charters called him back, and began to introduce us.

What prompted H.M. - whether it was his elephantine sense of humour, or some genuine purpose — I did not know. But H.M. cut in. "This," he said, pointing to me, "is Mr. Butler. He's drivin' back to London to-night."

"Yes, certainly," observed Antrim, without relevancy. "If you'll excuse me, gentlemen — er — supper. I didn't get any tea to-day, and I'm pretty well starved. Yes." Then he spoke to Charters, smiling with a bad assumption of ease. "I seem to have mislaid my wife. You haven't seen Betty anywhere about, have you, Colonel?"

Charters looked at him curiously. "Betty? No: not since this morning. Why?"

"Mrs. Charters said she thought she saw her getting on a bus. Er "

"Look here," said Charters in a flat tone, "what the devil's the matter with you, man? Speak up! What's wrong?"

"Nothing wrong. I just wondered "

"Stop that confounded jumping," said Charters testily. "You're not usually like this because Betty gets on a bus."

Antrim pulled himself together. Another thought appeared to have occurred to him, which he wished to dispel in our minds. He gave a sidelong glance at us, and spoke more genially. "Oh, I don't think she's running away or anything like that. Fact is, there's been a slight mistake. Nothing important, of course, and it's easily rectified; but it 'ud be damned awkward-" He stopped. "I suppose I ought to tell you. Fact is, a couple of bottles seem to have been misplaced or got lost in my dispensary. I don't think they're missing, and they'll turn up, but it's "

"Bottles?" said H.M. sharply, and opened his eyes. "What bottles?"

"It looks like negligence, and it would be bad for me. The trouble is, they're both little bottles of about the same size. And, to look at 'em, you'd think they contained the same stuff. Of course, they're both labelled, so there's no harm done. One is potassium bromide, ordinary nerve sedative, in the crystalline form. But the other, worse luck, contains strychnine salts — very soluble stuff."

There was a pause. H.M.'s face remained wooden, but I saw that he was biting hard on the stem of his pipe.

CHAPTER THREE

The Shutters of Suburbia

It was a quarter past nine when I set out on my weird travels. I ate a plate of sandwiches and drank a bottle of beer while a route was mapped out for me to Moreton Abbot, some ten miles away. Things did not now look so bad: with luck, I should be able to get the business done and return to Charters's by midnight, with everything off my mind. I did not realize the nervous strain under which I was fuming, although the sandwiches seemed tasteless and the beer flat.

H.M. and Charters I left in the latter's study. Both were very worried over Antrim's information. As I was going out, I remember Charters's saying that he would show H.M. some exhibits in the Willoughby case, whatever it might be. I also noticed that the blue Hillman touring-car was no longer in the drive outside the bungalow. Stowing away the Compleat Burglar's kit under a rug in the tonneau — it was more of a cursed nuisance than anything else, since I meant to use only the skeleton keys or the glass-cutter — I climbed into H.M.'s Lanchester and let drive for the great adventure.

It was not quite dark. A strip of pale clear sky lay along the west, but smoky blue had begun to obscure it; and below, along the main highway, street-lamps were winking into flame. The lane down which I ran the car was deeply shadowed. On either side were high hedgerows, and beyond them white-blossoming apple trees. In short, all was peace — for precisely fifty Seconds. I had come to the mouth of the lane opening into the main road. In the highway was the homely sight of a bus stopping by a street lamp, and somebody in a white linen suit climbing down. Then, in the hedgerow to my right, there was a sound of violent crackling. Somebody said, "Pss-t!" A face, looking paler by reason of the gloom and its mahogany-coloured hair, was poked through the hedge. It was followed by a shambling body, and, as I stopped the car, Dr. Antrim laid his hand on the door.

"Excuse me," he said. "I know you'll think this is confounded cheek, but it's pretty urgent. My own car's gone bust — no time to fix it — you know. They said you were driving to London to-night. Could you manage to drop me off at Moreton Abbot?"

This was dilemma before the adventure had even begun. Antrim's eyes appeared to have a steady shine in the gloom.

"Moreton Abbot," I said, as though the name were unfamiliar. "Moreton Abbot? What part of Moreton Abbot?"

"Valley Road. It's just on the outskirts. Dignity be damned, no time for dignity now. It's very important," urged Antrim, running a finger round under a tight collar. "Fact is, a patient of mine lives there. Name of Hogenauer. It's very important."

If I didn't take him, he would probably take a bus and go anyway. If I did take him, it might wreck the whole of my little enterprise; but at least I should have him under my eye and know when I could start housebreaking in safety. Nevertheless, the decision was taken out of my hands. The passenger who had got off the bus in the main highway had just turned into the mouth of the lane. I saw a stocky man in a white linen suit, wearing a straw hat and smoking a cigar. The man hesitated, and then came towards the car.

"I wonder if you could tell me " said a familiar hearty voice, in an almost deferential tone, and then broke off. "Well, well, well!" it crowed. "If it isn't Blake! Imagine running into you down here! How are you, Mr. Blake?"

The last light shone on the alert pince-nez, with the little chain going to the ear, of Mr. Johnson Stone — still on H.M.'s trail. Stone's round, fresh-complexioned face was turned up with great amiability, but he had the look of one whose inner temper is wearing thin. Even as he extended his hand, a new thought appeared to strike him.

"Here," he said in a somewhat aggrieved tone, "were you holding out on me? Did you know where Merrivale was after all? I've only just tracked him down. Out of the pure goodness of my heart, just to do him a favour, I've hunted all over England for him when I was supposed to be taking a holiday; and right at this minute I'm supposed to be visiting my son-in-law in Bristol. If you people have been holding out on me — "

"Beg pardon, sir," interposed Antrim curtly. Antrim had been looking steadily at me. "I understood that this fellow's name was Butler."

"Well, it was Blake when I met him in London," answered Stone, regarding him curiously. "But it's possible that he's going round in disguise as well as the rest of 'em. I'm getting a little tired of all this."

"It's possible he is," said Antrim in a curious voice-and then his big figure disappeared through the gap in the hedge. Stone blinked. There was a pause.

"I'm sorry if I've spoiled anything, he said calmly, "I wouldn't have, if I'd known. But that took me off balance, and if you intend to go around giving false names you ought to let me know in advance. I've always regarded the English as a pretty level-headed sort of people, but, so help me Jinny, this is the queerest country I ever got into! I ought to be in Bristol to-night. And if I ever do catch up with Merrivale, which seems unlikely —‘

I let in the clutch. "He's up there. But there's one thing I'd ask and plead of you: for God's sake stop harping on that tedious joke about disguise — particularly when you meet H.M. And whatever else you do, don't mention his hat."

The car moved down into the main road. I had the satisfaction of seeing Stone put up a hand bewilderedly to his pince-nez, and of creating some mystification on my own account. He seemed to be puffing vigorously at his cigar. But Antrim had bolted like a rabbit at the mention of a false name: why? I had lost any chance I might have had of learning something from Antrim, though it was some consolation to reflect that I hadn't the remotest notion as to the subject on which I might have learned something. It was all a game in the dark, and very shortly I would literally be playing a very dangerous game in the dark.

I took my time over that drive to Moreton Abbot, leaving Torquay by a roundabout way through the deep lanes. But, when I wound into Moreton Abbot, the first street I found was Valley Road. It was very long, very broad, not too well-lighted, and a picture of suburban respectability. There were long ranks of detached and semi-detached houses, neat and low-built, in stucco or brick or stone, imaginatively or sedately painted, but all looking curiously alike in their mere closeness to each other. Each had a small front-garden minutely laid out with flowers. Each had a brown-painted gate inscribed with some more or less relevant name. Most of the houses were lighted; cyclists toiled along the road with plodding pedals; and through an open window a radio was talking hoarsely.

Though it is usually next to impossible to find a house by name rather than by number, I cruised past "The Larches" almost at once. The name was fresh-painted on the gate. It had (surprisingly) a larch like a stunted pine-tree growing on either side of a white-painted front door, and it looked even more respectable than its neighbours. But I was relieved to see that the houses on either side were already dark. There appeared to be an alley running along the rank at the rear, and it might have been the safest way in unobserved; but alleys usually mean watchdogs.

I drove on for several hundred yards, and swung into a gloomy turning labelled Liberia Avenue, where I could stop the car and consider. The question was how far away I should park the car. I pulled up to the kerb and lit a cigarette.

And at the same time a hand fell on my shoulder from behind.

A very large policeman was looking down at me in the twilight, with a sort of sad and gloomy satisfaction like Monte Cristo in the melodrama; by the glow of the dashlamps I could see the sergeant's stripes on his arm. At the same moment another policeman appeared at the front. of the car, directing a beam from a bull's-eye lantern at the number-plate.

"You're under arrest," said the sergeant. "I have to warn you that anything you say will be taken down and may be used in evidence- That the right number?" he added over his shoulder.

"Ah," agreed his companion. "AXA 564. That's it. Bit of luck, this. Then they both looked at me intently. "Sst!" warned the second man, after this sinister pause. "Black bag, sir. Black bag that they told us to look out for."

"Right," said the sergeant. He examined the front of the car, finding nothing more significant than my feet; then he looked in the rear, felt under the rug, and with granite triumph produced the case of the Compleat Burglar. "Out you get, my bucko. Got any objection to my opening this?"

By this time I had (somewhat) got my wits about me.

"I have. A very strong objection. Don't talk rot. In the first place, you've got your formula all wrong. Before you put a man under arrest, especially somebody who's innocent, you're supposed to tell him what he's charged with."

"I don't mind," answered the Law grimly. "For a starter, with the theft of a motor-car. And then we'll go on to grand larceny. Since you know so ruddy much about legal forms, you'll know that the maximum sentence for grand larceny is fourteen years."

"Who charges me with all this?"

The sergeant permitted himself a grunt approaching a laugh. "A gentleman named Sir Henry Merrivale and Colonel Charters, who happens to be Chief Constable of thissur county. Eh, Stevens?"

For a second or two I tried to convince myself that this was not a bad dream. With that peculiar cussedness and cross-purpose which always dogs my adventures under H.M.'s direction, it was plain that some mistake had been made; but, in the devil's name, what mistake? This was obviously H.M.'s Lanchester. I knew it as well as I knew my own car at home. Yes, but suppose H.M. and Charters hadn't sent out any such charge at all? Suppose this was a first attempt of the cloudy Enemy? There came into my mind Charters's mention of his secretary, named Serpos, and Charters's comment: "An expert mimic when you get him started." Whereupon I fixed the sergeant with a hypnotic eye.

"Look here," I said. "You're making a mistake. There's no use arguing with you: all I want to do is prove you're making a mistake. I'm on a very serious mission for the Chief Constable. Let's go along to the police station, by all means; you give me two minutes at a telephone, and I'll prove it. Isn't that fair enough? Neither Sir Henry Merrivale nor Colonel Charters ever sent any such message as that."

The sergeant looked at me curiously. It is never wise to say too much. Then he climbed into the back of the car, keeping his hand on my shoulder.

"Hang on to the running-board, Stevens," he ordered. "You drive straight on. Yes, it's fair enough: if you can prove it." He chuckled. "Bluff don't go down with me, my bucko. General alarm was sent out twenty minutes ago from Torquay police station. And the two gentlemen you spoke of came in person to turn in the alarm. In person, my bucko. So they didn't send it out, didn't they? They turned in them charges against you. They also said to keep an eye out for a black bag you would be carrying."

"Sergeant, everybody can't be crazy. Who am I supposed to be?"

"I dunno, answered my captor, with broad indifference. "You've probably got plenty of names. They said one of the aliases you might use might be Kenwood Blake."

I took a deep breath and a firmer grip of the steeringwheel, but the car almost stalled as we set off. If this was for some reason a genuine trick played by the mysterious-moving two who had sent me on this expedition, all I could say was that it was a damned dirty, low-down trick. But I couldn't credit that. I also played with the idea that these might be bogus policemen, though that melodramatic notion was soon dispelled.

The police station was in Liberia Avenue, where it curved to the left only a hundred yards or so from the main road. It was a low-built converted house, set back from the street in a paved yard, with an arc-light burning over the door. My captors took me out of the car and marched me with stately triumph into the charge-room. Behind the desk a fat sandy-haired sergeant, with the collar of his tunic unfastened, sat writing in a book. A clock on the wall over his head said ten minutes to ten. I saw, with unholy relief, a telephone on the desk.

"Got him the minute we stepped out of the station," said my sergeant, and his colleague at the desk whistled. "All in order. Here's the black bag. He wants to phone Colonel Charters. Yes: we'll ring up Torquay and make the report. Stevens — put him in there." He nodded toward a door at the back of the room. "Now, now, this part of it's private, my bucko! You'll get your chance to speak."

I had no choice. The careful Stevens opened the door into a little low room with a back door and a back window, after which he poked his head out of the window. Despite the dusk figures and faces were still distinct, and there was a bright arc-lamp in the rear yard. Two policemen were tinkering with the motor of an Austin police-car, while a motorcycle man looked on: there was no possibility of a jail-break. Then Stevens hurried into the outer room, shutting the door, to listen to what promised to be a highly interesting conversation by telephone. It was. I was down on the floor, in a highly curious posture, with my ear to the crack under the door, and probably as boiling mad as anybody in the British Isles.

After getting through to Torquay, the sergeant exchanged some amenities in a leisurely fashion. "Ha ha," he said. "Yes, we've got him safe enough. Smart work, eh? Do you think I could speak to Colonel Charters? No, not the superintendent! Yes, Colonel Charters! He personally instructed me," declared my beauty of a sergeant, with pompous intonation, "to — well, try his private wire, then. He's probably at home." There was a long pause. "Not in? Well, is there a gentleman there named Merrivale? No? Any message? This fellow tried a great bluff that he wanted to talk to him. Is there any, message?" Then the sergeant appeared struck dumb with surprise. "Not to charge him? What do you mean, we're not to charge him? He's accused of-"

Another long pause ensued, while there seemed to be explanations: and then gradually the sergeant's tone changed, into a roaring chuckle.'

"No!" he said. "No? You don't say! Well, well, well!" (By this time my curiosity and wrath had reached almost a point of mania.) "Is that so? And he probably thought he was doing well, I suppose, the poor fool. Ha ha ha." He grew serious. "Yes, but if neither of the gentlemen will charge him, what are we going to do with him? What did they say? Ah! Yes, that's the best thing. I'll tell you what: we'll put him down in the cells for to-night. Then we'll bring him to Torquay to-morrow morning, and they can talk to him. About eleven o'clock, say? Right. How are the wife and kids?"

And at eleven-thirty to-morrow morning I was due for a very different sort of appointment.

I scrambled up off the floor, at that state where fury becomes, coolness and clear sight, to make an inspection of the room. It was a bare enough place. A green-shaded lamp hung from the ceiling, over a deal table with a well-thumbed detective-story magazine on top of it, and a couple of kitchen chairs around. There was a sink and water-tap, with a dissipated-looking roller towel hung up beside it. But my eye was drawn to the three wooden lockers built against the wall. Inside the first locker I found what I had hoped to find: a uniform-tunic neatly arranged on a hanger. There was a helmet on the shelf above, a belt coiled beside it, and a bull's eye lantern. As H.M. had noticed, I was wearing a dark blue suit, and my own trousers would suffice. It took just ten seconds to put on the tunic and helmet, buckle the belt round my waist, and hang the lantern from it, in order to become the Compleat Policeman. It wasn't a bad fit. From the outer room I could hear the sergeant still droning at the telephone; and, through the open window to the rear yard, somebody was commenting on the lascivious habits of carburetors. The back way was the only way out. And I admit that I was feeling queasy in the stomach when I approached it.

I backed out of the place, as though I were turning round to close the door behind. Six steps led down into the yard. If the men in the yard glanced up, as they naturally would, they would see a familiar back and helmet. The great dangerpoint was that arc-lamp over the door. My legs felt light, and the queasy feeling had increased, when I carefully closed the door. Then I turned round full under the arc. At the same time I casually switched on the lantern, and swung the brilliant beam straight in their faces. They were all bending over the engine of the Austin, so that it caught them flat.

"Gaa!" roared one, and jumped. "Take that blasted thing What's the game, Pierce?"

They had all looked away. I came down the steps, not too quickly. The light bad to be moved, but I could count on about a second's blindness after it. At the rear of the yard was a tolerably high wall, with double gates giving on an alley. I heard my own footsteps ringing on the pavement of that yard, with an almost goose-step regularity in my effort to keep them slow. I didn't dare look round now, for I had a feeling that eyes were on me.

A voice said, "That's not Pierce," — and I cut loose for it.

The rear gates were only two feet ahead now, and there was a padlock and chain hanging loose from them. Those gates were spiked at the top, so that it would want careful climbing to get over them. I jumped through, slammed the gates with a crash like a falling lift, closed the padlock, and pitched away the key. For the first time I glanced behind. There were no shouts from that yard: no shouts, and no fuss. They were coming for me as quietly as a cage of animals, black against the light, and one arm came through like a paw as the gates crashed. The rear door of the station was open now, and a voice was calling with deadly efficiency:

"Thompson, over the wall. Dennis, through the sidegate next door and up the alley. Stevens, up the street as far as you like and get him from the front. Pierce-"

This was something like a chase to rouse a man's wits. While I ran up the alley, the geography of the place became clearer. In coming into Liberia Avenue from Valley Road-, I had made a left-hand turning, and the police station was almost at the end of the former street. It was a right-angle. If I doubled back now, I could get into the alley running at the rear of Valley Road. If I stayed in the open, they could nail me easily. It became clear that my only sanctuary was the place where I had originally intended to go: "The Larches," an empty house. The attention of householders I was not afraid of; my uniform was the best kind of security against that; and the neighbourhood would shortly be buzzing with policemen.

I was pelting in the dark along a narrow, rocky alley with garden walls on either side. Each had its ash-bin outside, and the roof of its miniature greenhouse faint-gleaming by starlight over the wall. High up behind me a beam of light shot out, and I saw one of my pursuers poised on the wall over the police station gate before he jumped. Hitherto the night had been so quiet that I heard the thud when he landed in the alley: but now the dogs began. That devilish din of barking masked the noise when I overturned a few ash-bins in the path of the man behind me. I had stormed round the turning now, into the lane behind Valley Road, so that his light could not find me. From behind there was a crash as apparently he met one of the ash-bins, and the light vanished; I hoped to heaven he had broken it. But people were moving in Valley Road itself, out beyond the houses between, and even at that considerable distance a white beam pierced through the trees into my face.

They were closing in. Several windows in the neighbourhood were going up with a bang; I could discern the heads of early-retiring householders poked out like turtles. My only course now was to switch on my lantern.boldly, beat the brush with a halloo, and pretend to be a real policeman searching for myself-while hoping with some fervency that I could find the back gate of "The Larches." That was the snag. Every one of those cursed gates looked alike. I was panting hard when my lantern flickered over one fence, into a tidy garden with paths laid out in white pebbles, and caught a larch-tree as neatly as you catch a fish. It might be a coincidence, but I should have to risk it. I pulled open the gate, closed it behind me, and ran smack into bottles.

There seemed to be dozens of bottles. They were ranked up just inside the gate; my imagination magnified them into a forest even as my foot sent them rolling and clanking and bumping as though they were alive, with din enough to rouse everyone in Valley Road. To taut nerves they became monsters. I turned my lantern down while I seemed to slip and wade in empty bottles. They were not even honest beer-flagons, but they had contained a particularly villainous brand of German mineral-water — with a taste rather like Epsom salts-which I remembered by the blue-and-red label. So far, the houses on either side of "The Larches" had remained dark and quiet. But now, in the house to the right, an upstairs window was half raised. I saw a woman's head in curl-papers edged in the window as though she were listening at it, and heard a voice speaking shrilly to me.

I steadied myself, and tried to get my breath.

"Sorry to disturb you, madam," I said, with a heavy imitation of a Force manner, "but there's an escaped murderer loose. He's a homicidal maniac, and the neighbourhood ought to have been warned, but don't worry, we'll catch him."

The window went down with even greater celerity than I had hoped for, and the curtain swept over it. I stood alone among bottles, sweating blind and listening to my heart bump. It had become uncannily quiet again. The dogs' barking was dying away. Even the pursuit, though that was quiet enough, seemed to have taken another direction. I could not understand why — unless they had spotted me, and were silently closing in.

Nothing stirred except a faint wind in the trees. Suburbia (which some, I believe, are foolish enough to call dull) was dozing under clear starlight. I went quietly up the path, which was outlined along its borders with white pebbles, past geometrical flower-beds and a tall post supporting a radio aerial. The scullery of "The Larches" projected some dozen feet from the flat line of the house. Besides the scullery door, and the door to a coal-house, there was a third door facing out on the garden. To the right of this were two windows, closely shuttered. These were undoubtedly the windows of the mysterious back-parlour, through a chink in whose shutters Sergeant Davis had seen the lights flicker round "a thing like a flower-pot turned upside down."

Even while I was wondering how I should be able to get into the house without any of the Compleat Burglar's kit, I found myself approaching those windows. It seemed an ordinary suburban house, and yet I did not like it, It looked wrong.

I went up to the window nearer the door, and tried to peer through the slits in the shutter — without result. It was dead black inside. Even when I put my lantern to the slit, and tried to look in alongside it, there was only a blur. The window itself, however, did not appear to be closed. Next I tried the farther window. As I put the lantern to the chink, it made a faint rattling sound on the wood: and I could have sworn that there was a movement in the room. I could not identify it — it was something like a rustling — but it almost made me drop the lantern. This time the slit was a trifle larger, so that I could see something very dimly and darkly on the edge. It was something of rounded shape, like the back of a chair. And projecting over the top of it, at a queer unnatural angle, was something like a flower-pot turned upside down. It seemed to be of the same reddish colour, although I could not be certain in that blur, and it did not move. There was no reason in the world why such a sight should seem horrible to a prosaic-minded man in a suburban garden: I can only tell you that it did. As I stood back from the window, wiping my forehead, I heard the rustling movement again.

I tried the shutters. Both were tight-fastened. More as an automatic gesture than with any hope, I moved along and tried the knob of the door. But the door was unlocked.

Though I tried to ease it open gently, the thing creaked and cracked at every foot. Ahead was the main hall of the small house, with the front door facing me some thirty feet ahead. And that front door was now open. In the aperture, the key of the front door still in his hand, a man stood silhouetted against the faint glow of the street-lamps outside, looking at me.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Poison-Bottle

"Who's there?" a voice said with a quick and shaky start.

For reply I pressed the button of my lantern, turning it sideways so that he could see the uniform. If it had been chosen deliberately, I could have selected no better or more reassuring garb. I heard a sort Of 'Pluh!' of relief. The newcomer groped after a wall-switch, and the lights went up.

We were in a narrowish hall, somewhat frowsily kept after the spick-and-span exterior. There was a porcelain umbrella stand, and on one wall a Teutonic water-colour, circa 1870, of a girl in billowy skirts dancing before a table at which sat two resplendent officers with spiked helmets and beer-mugs. In the doorway — he still seemed reluctant to close it — the newcomer stood blinking.

He was a young man, small and slight, but his air or clothes had a portentousness which made him seem much Older. When not frightened (as he was now), his manner would be grave and somewhat superior. He wore his hair slicked down, parted at the side and brought across his forehead in a slight curve after the fashion of the Old-style barman. His features were sharp, rather hollowed under the cheek-bones, but with good-natured, cocky eyes and a cocky shoulder. No one, he seemed to say, would get the better of him. He wore careful dark clothes, with a wing collar and black tie: also, he carried a bowler hat and gloves. His accent was the accent of London. This, beyond doubt, was Hogenauer's servant, who was supposed to be out with a girl. If I had gone through with my burglary scheme, I should have had a very thin time of it.

"You put the wind up me, you did," he declared accusingly. "What's the game?"

"This door was open," I explained. "I looked in to make sure everything was all right. We're after somebody in the neighbourhood, and..’

"Ere!" he said, galvanized. "You don't think the beggar's in this house, do you? Who are you after? It must be somebody dangerous. The whole street's full of coppers."

It was; and that was the trouble. I reassured him instantly that there was nobody in the house, for I was afraid he might go out and bawl for all the rest of the police. It was a ticklish position, and I wished to God he would come in and close the door. There were familiar footfalls in the road outside as my late friends patrolled it: there was I, standing smack in the middle of a bare narrow hail illuminated like a theatre, Open to the inspection of anybody who passed. But I couldn't duck back to hide, Or even order him to close the door, in case it roused his suspicions. While he fiddled with his cuffs, and looked hesitantly from the street back to me, the footfalls clumped nearer…

"It's a long job," I grumbled, and turned towards the back door. "Well, I'll be getting on."

"Ere, stop a bit!" he protested, and did what I had hoped for. He closed the door and hurried towards me, evidently wanting to keep a policeman at his elbow when there were cut-throats in the suburbs. He produced a packet Of Gold Flakes, and became persuasive. "NO need to rush Off, is there! 'Ave a fag. Gaow on; 'ave one. There's nobody to mind the smoking. Your sergeant needn't see you, and my governor's away for the evening. There you are!"

"I don't mind if I do," said the Law, relaxing his sternness. "Thank you kindly, sir. You're Mr. Hogenauer's gentleman, aren't you?"

Now this was very much overdoing the bobby-business,

but the other took to it. He nodded with an air of good-natured condescension as he lit a match. "That's me, constable. Bowers is my name — Henry Bowers, at your service. Only been at this job two weeks. Of course, the job is — but — " The dashes do not indicate words, but shrugging gestures which I could not quite interpret. "But never mind that," he said with ghoulish eagerness. "Who is it you're after? What's he done? Is it murder?"

Since he now appeared to have no idea of calling in anybody else, I piled it on rather thickly about a burglar-murderer who had robbed the Chief Constable of the county. "So it's a good job you're indoors, sir. Funny thing, though. How does it happen that, if the boss is out for the night, you're in? I wouldn't, if it was me."

Bowers shifted. "Ah, that," he said. "That's my conscience. Do I have a cushy job here? Do I appreciate it? Not half!" He became confidential. "Good wages, not much to do, and every night off if I want it. So I don't take any chances with it. I pay attention to the emperor, whatever he says. See?" Drawing down the comers of his mouth and half closing his eyes, Bowers tapped his chest with an air of profound shrewdness. "Well, this morning after breakfast he says to me, 'Harry, I'm going to Bristol this evening.' And laughed when he said it. 'But,' he says, you might come in early to-night, because I may have a visitor'

"He said he was going to Bristol, but still he expected a visitor?"

"That's it. I tell you straight, I often think the governor's a bit-" Bowers tapped his forehead significantly. "Ruddy queer sense of humour 'e's got, and I never know whether he means what he says or not. So I do whatever he says. See? I'll tell you how it was.

"This morning after breakfast, as I say, he said he was going to Bristol in the evening. I says, 'Shall I pack a bag?' He says, 'No, I won't need a bag,' — and laughed again. I says, 'You'll be at Dr. Keppel's, I suppose?' (This Dr. Keppel is another Squarehead, sort of a professor, who lives in a hotel at Bristol.) He says, 'Yes, I'll be at Dr. Keppel's, but I don't think Dr. Keppel will be there; in fact, I've got every hope that he'll be out.' Then was when he told me we might have a visitor tonight. I ask you!"

The reason for Bowers's loquacity I could see in his own uneasiness. He was smoothing at his dark, slicked-down hair, and peering into corners of the hall. But this gave a new turn to possibilities in the business. It would appear that Hogenauer himself might be intending to do a spot of burglary, or at least secret visiting: that he was going to pay a quiet call at Keppel's hotel when he could make sure Keppel was out: and that the `visitor' he expected here might be Keppel himself, brought on some wild-goose mission. Why?

Such a possibility had clearly occurred to the far from dull-minded Bowers.

"So I thinks to myself," says Bowers, with a sort of pounce: "the governor goes to Bristol, and Keppel comes here. Eh! The more so, mindyer, because Keppel's right here in Moreton Abbot — or he was this morning, anyway. Keppel came here this morning, dropped in about eleven o'clock, and had a talk with the governor. I don't know what they said, because they talked in German, but the governor gave Keppel a little packet like an envelope folded in half. Very friendly, they was. Oh, yes. Of course, it's none of my business, but, I tell you straight, I didn't like it."

I gave an imitation of a man pondering heavily.

"But your governor," I said, "told you to come in early to-night. You didn't come in very early, did you?"

"No, and that's just it," cried Bowers, with a sort of defensive aggressiveness. "Because why! I'll tell you. Because, the last thing my governor said this afternoon… I went out before he did, just after I gave 'im his tea… the last thing he said, in that quiet glassy-eyed way of his, was: 'Yes,

Harry, I think you may have a visitor to-night, but I doubt if you'll see him'."

There was a pause. It was not a comfortable pause.

"Now I ask you," said Bowers in a cooler tone.

"Here! You think your governor — or Keppel — was up to some funny business?"

The other evidently saw that he had gone too far. "Not my governor," he declared with quiet earnestness. "That I'll swear to. You know that: anybody at your police station knows that. He was much too anxious to keep on the good side of the slops. He's a foreigner, d'jersee? He's registered at the police station, but he's always been in a stew and sweat for fear they'll make him leave the country at the end of six months or nine months or whatever it is. Not him! Why, I could tell you-"

"You could tell me what?"

I became aware that I had either altered my voice or overstressed by curiosity as a policeman. There was a subtle change in the atmosphere of the hall. Though he tried to seem casual, Bowers was studying me with his head a little on one side, and in his small quick eyes there was a dawning of what might be suspicion.

"See here, mister," said my little cock-sparrow, and took a step forward, "just 'oo are you, anyhow? Sometimes you talk like a copper, and sometimes you don't. Sometimes you act like a copper, and sometimes you act like-"

Before his mind could jump any farther along that line of thought, something had to be done. "I'll tell you what I am," said the aggressive Law. "I'm a man who means to get on in the world, that's what I am. I mean to be a sergeant before I'm many years older. Understand that, cocky? And, if you want to know it, that's why I've been watching this house for some time."

"Go on!" he said, and fell back.

"We know that there are things in this house that want explaining. We know that three nights out of a week your boss locks himself up in the back parlour, with shutters on the windows. But we've seen an odd kind of light through that window — I've seen it myself. We know he's working on an invention or an experiment of some kind. What is it? It's not only what we want to know; it's what Scotland Yard and the Foreign Office want to know."

"Come off it," said Bowers with pale scepticism, after a pause. But his eyes remained fixed. "Why, I'll tell you straight," he added quietly, "there's nothing in that room. Don't I know it? I tidy up there every day. And there's nothing at all except a lot of books. He don't even keep anything locked; not even his desk. I've looked. If he wants to shut himself up there in the evenings, that's his business, but he don't work at any experiments there. You want to see? I can show you right now."

He was pointing towards the door of the room, on the left-hand side as you faced the rear of the hall. Then he looked at it, and moved a step closer, and his voice went up a note or two.

"The key's in it on the outside," he said, "and where the hell's the knob?"

"What's wrong;"

He was jabbing his finger at a small octagonal hole from which the knob on its spindle should have protruded. Both knob and spindle were missing. But the key was in the lock, hanging almost loosely enough to fall out. Bowers opened his mouth, hesitated, and then went down like a terrier to search on the floor. It was bare floor except for a thinshanked chair not far from the door: but under the chair he

found what he was looking for. He found a knob of bright brown terracotta, loosely fitted on the spindle. But there was no knob on the other end of it.

Then Bowers found his voice.

"There's somebody in there," he said. "Dontcher see what happened? The knob inside's been loose for a long time; the governor asked me to mend it for him. Somebody went in there, and shut the door. Then somebody tried to come out. But the knob was loose and wouldn't turn the rod, and he fooled with it, and pulled it in and out, and then this came away and fell on the floor. And now he's in there and can't open the door. The door ain't locked, but the latch is caught and it's as good as a lock becos he can't turn it. And now he's in there, with the other knob in his hand…"

"Hogenauer?"

"I shouldn't think it was very likely, should you?" said Bowers simply. "No. Not the governor. But there's that burglar loose that you coppers are chasing-"

I took the knob and spindle out of his hand. At the same moment we both heard a noise, a sort of rushing noise, on the other side of the door. Without any warning, with no change of expression, Bowers started to make for the front-door to get out into the street. I lunged and got hold of his arm, or in a few seconds more we should have had the place invaded by my friends from the police station at Bowers's call. With some fumbling I got the spindle into place, holding Bowers's arm with my other hand; then I turned the knob and pushed the door open.

It was dead black inside. There were no sounds now. Bowers was quietly shaking in my grip, pressing up against the wall to get out of the line of the door, and he spoke with fierce calmness. "Are you loopy? Blow your whistle, you fool. There's a dangerous.."

I groped along the wall for a light-switch. There was a switch, but when I clicked it no response came. I still had the lantern hanging at my belt. Its broad beam swept across the room towards a wall of books; then it turned to the right and stopped. Along the right-hand wall were the two shuttered windows. Across the room, some feet out from the farther window was a broad claw-footed table; behind that table, and sideways to the door, stood a low padded armchair; and in the armchair a man sat grinning at me.