Homero Aridjis has always said that he was born twice. The first time was to his mother in April 1940 and the second time was as a poet, in January 1951. His life was distinctly cleaved in two by an accident. Before that fateful Saturday he was carefree and confident, the youngest of five brothers growing up in the small Mexican village of Contepec, Michoacán. After the accident — in which he nearly died on the operating table after shooting himself with a shotgun his brothers had left propped against the bedroom wall — he became a shy, introspective child who spent afternoons reading Homer and writing poems and stories at the dining room table instead of playing soccer with his classmates. After the accident his early childhood became like a locked garden. But in 1971, when his wife became pregnant with their first daughter, the memories found a way out. Visions from this elusive period started coming back to him in astonishingly vivid dreams, giving shape to what would become .

Aridjis is joyously imaginative. has urgency but still takes its time, celebrating images and feelings and the strangeness of childhood. Readers will love being in the world he has created. Aridjis paints the pueblo of Cotepec — the landscape, the campesinos, the Church, the legacy of the Mexican Revolution — through the eyes of a sensitive child.

Homero Aridjis

The Child Poet

Introduction

MY FATHER HAS ALWAYS SAID that he was born twice. The first time was to his mother, Josefina, in April 1940, and the second time was as a poet, in January 1951. His life was distinctly cleaved in two by an accident. Before that fateful Saturday he was carefree and confident, the youngest of five brothers growing up in the small Mexican village of Contepec, Michoacán. After the accident — in which he nearly died on the operating table after shooting himself with a shotgun his brothers had left propped against the bedroom wall — he became a shy, introspective child who spent afternoons reading Homer and writing poems and stories at the dining room table instead of playing soccer with his schoolmates.

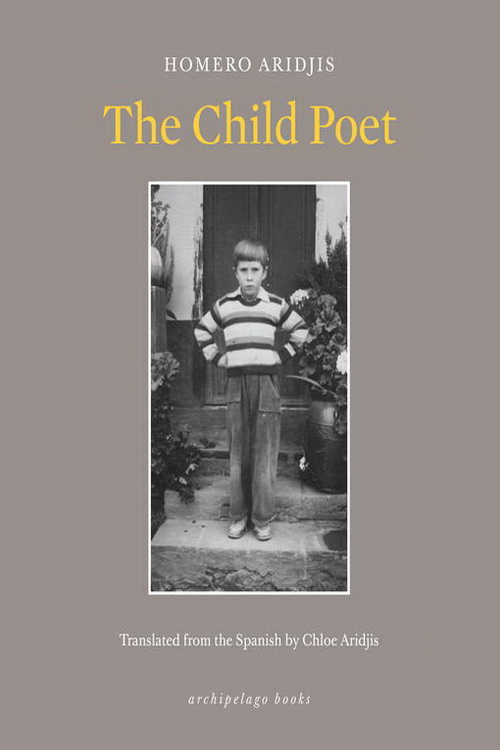

There are precious few photographs of my father before his accident. One in particular offers a tender portrait of the boy who was left behind, and the scene of his shaken paradise. Frowning in the sunlight, he kneels beside Tarzan, the first in a line of beloved dogs. On the garden wall behind them hang two of my grandmother’s many birdcages, most likely holding songbirds in midchorus.

It is of course tempting to imbue this pensive face with the intellect of the man to come. His expression is one of a heightened sensibility, his gaze fastened on something beyond the present. One senses shyness and self-assurance, a precocious gravitas but also vulnerability. The truth is, I will never really know who my father was at the time. Nor will he. After the accident his early childhood became like a locked garden.

And then, in 1971, the memories found a way out. As soon as my mother became pregnant with me, visions from this elusive period started returning to my father in astonishingly vivid dreams, giving shape to what would become El poeta niño, a celebration of his life before 1951. Imminent fatherhood helped revive memories that had, for two decades, lain dormant.

This work, narrated in a succession of interconnected vignettes, has provided me with a portrait of my father in his pre-poet years. I have grown to know the child at a time when sights and sensations were still delivered at their purest, when each day brought new perceptions of his mother and his father, when every villager in Contepec formed part of a personal mythology. It was a time when shadows were palpable and light had a sound of its own.

I began work on El poeta niño in a translation class at Harvard in autumn 1993. After translating half the book for my course, I was keenly encouraged by my professor to translate the other half. For mysterious reasons of the psyche — perhaps I needed to write my own book first — it took twenty years for me to complete the task.

Now, as then, translating my father’s text has been an exceptional experience. This has always been one of my favorite works of his, and the fact that its gestation was parallel to my own makes it especially poignant. And its main themes — childhood reverie and artistic solitude and apartness — were ones that would preoccupy me for years to come.

The structure of the book — vignettes — remains faithful to the method of composition, a sequence of loosely related dreams. Many of the passages stand on their own but they also form part of the larger mosaic of childhood reverie. After all, the language of the child, as Gaston Bachelard has described at length, is a language of images that acquire an oneiric quality when returned to later in life. “We dream while remembering. We remember while dreaming.”

There is certainly a forward movement to these pages and a distinct rhythm that emerges, but more than anything, it is a celebration of the image and its reverberations. For this is the cadence of reverie, and of a time when one’s perception of the world arrives in fragments. I tried to preserve the poetic simplicity of the child narrator and remain faithful to his rendering of the world around him, opting for words that suited a younger vocabulary.

I also had to accept the strangeness of having Mexican characters converse in English, and of reconstructing such a determinedly Mexican village and landscape in another language. My grandparents, their house, the main square, the village cemetery: coordinates from my own childhood, engraved in my mind long before I’d read the book. I was confronted with the transformation of a place and a people I knew intimately into characters inhabiting a literary landscape. Yet the themes, albeit explored within the frame of a small Mexican village in the 1940s, are universal.

My father never intended to write El poeta niño; it was created out of the necessity to retrieve his childhood. I once asked him about the actual process of writing the book. Because all memory is relative, he replied, it was difficult to avoid modifying his memories. They are vulnerable to subsequent experience and of course to the language in which they are lived and acquired and later recorded. Not to mention that the very act of transforming dreams into text is in itself a form of translation, and at best an approximation of the original. While writing, my father became a reader of his dreams, and while putting them to paper, he could not help but interpret them as well.

So perhaps this is a translation at twice remove; even so, I hope to have captured some of the mystery and wonder of my father’s childhood, the childhood that made him a poet.

CHLOE ARIDJIS

The Child Poet

Not a footstep was to be heard on any of the paths. Somewhere in one of the tall trees, making a stage in its height, an invisible bird, desperately attempting to make the day seem shorter, was exploring with a long, continuous note the solitude that pressed it on every side, but it received at once so unanimous an answer, so powerful a repercussion of silence and of immobility that, one would have said, it had arrested for all eternity the moment which it had been trying to make pass more quickly.

To my parents

~ ~ ~

Chapter 1

TO SUCKLE. The world was an immense tit, a mountain the size of my mouth. Fingers. Pacifiers. Suction. Female faces with a maternal presence. White instants. Milky light.

The concave hour. The warm crib. And I, center of the room, awaiting the punctual breast, which would transmit to me, like a cornucopia, life itself.

Her breast, like a supple moon or bread, flinched at my bite; between my hands, which lifted it bare to my lips and savored it hungrily.

A brimming cup, it would separate in a soft incarnation from the chest that bore it.

Enveloped in the morning light, from which I suckled brightness. And it was a sun to grasp, my face burying itself in its landscape.

My mother’s footsteps in the corridor. A door opening or closing. Rain on the roof.

My thoughts drifted towards my father in his store. I imagined him entering the room, sitting down on the edge of the bed, and remaining by my side.

But he didn’t. And all of a sudden I would find myself calling out “¡Papá! ¡Papá!” knowing well that as soon as he heard me he’d drop everything and come at once.

And he did. He would sit down by my side and I would watch him, in his fabulous existence, until I fell asleep again.

In darkness I would awaken, not knowing on which side of the bed I was lying. And, feeling the emptiness before me, I would grope around, in search of another comfortable position.

Finding the pillow meant finding the place where my head should have been. But just when I thought I had, I found myself touching the other end of the bed.

I felt battered, full of shadows and confusion, unable to wake up altogether, unable to fall back asleep.

Until the window loomed into view, scarcely lighter than the dark walls. And I would slowly pronounce my own name, as if reassuring myself, adrift in the vast expanse of my bed, that I was still the same person.

I would remember, in the distant, distant past, the moment when my father left the room and I wasn’t able to stop him, filled with a sleepiness more powerful than my desire to bid him to stay. And, clutching the pillow so as not to lose myself, I would finally drift off, in the knowledge that when I woke I would see my father once again.

Awake the next morning, I’d postpone the actual moment of rising from bed. Out in the corridor the goldfinches chirped in their cages and the curtains and walls held a drowsy clarity.

As if inside a luminous sphere, I traveled within the day that brightened my room and, all eyes, would observe from bed the things that surrounded me, feeling an arousal of these things in myself.

In that clarity I could hear my mother’s footsteps, the maids’ voices, the flight of insects … And all of a sudden the house would fall silent, as if everyone had left, except the light.

I did not want to speak. An immense shyness hid the words from me. Moreover, I would think and rethink a sentence so many times that the moment for saying it passed, or it lost its meaning after so much repetition.

I felt fine within myself, and to explain or discuss anything implied a certain decanting of that self and was as tiring as taking a lengthy walk without water. I didn’t need to convince or be admired. I was happy as I was, keeping quiet, watching the sun illuminate the grainy, whitewashed walls and the frayed broom in the backyard.

It was difficult to emerge from myself. To express one wish entailed a long journey, as did the exposition of an idea or having to supply answers to questions put to me. Shyness made me twist inside like a rope, until I reached such extremes of pain that it was impossible to give it one more turn. My face burned scarlet, my features were overpowered by the heat, the ground gave way, my eyes betrayed my helplessness. I did not know where to turn and, ablaze with shame, took refuge in my own interiority like an armadillo in its carapace.

I’d remain within myself, inert, as if walled in, until my mother would say, “Come on, let’s go.”

And if there were others around, I followed her, anxious to disappear, like an actor who has made an entrance on the wrong stage and the audience, noting his bewilderment, discovers his mistake because he panics, and in his haste makes his exit all the more difficult and is unable to find the right door.

Thus was I bewildered by anyone who sensed my shyness, while I hid behind my mother, trying to not be seen, not be there.

From the moment we’d arrive at the home of one of her friends, and the woman or her daughters took notice of me, my main concern was to discourage everyone from addressing me in any way, for my mother was the best person to provide information about my tastes and reply to questions; even those which referred to my age, name, mood, and so forth, were best answered by her. I tried to prevent their curiosity from catching me off guard by feigning interest in a girl’s face or a dog in the room, which would lead inevitably to, “Do you want to play with Anna?” or, “Do you like the dog?”

I was surrounded by a magic circle, which no one should enter. This circle protected my intimacy, with its baggage of thoughts, fears, and desires. What I felt mattered only to me. To reveal my thoughts would mean revealing myself, to exhibit my desires meant exhibiting myself. And if I asked for something and it was denied me, my entire self felt rejected, for I had disclosed one of my soul’s necessities and placed it at someone else’s mercy. For this reason I did things on my own. And if someone went off because I didn’t show my interest, I would let that person go: their being remained within my being, in my thoughts.

I liked going for walks alone and being alone, traveling through the day as through a reality as wondrous as the imagination, where the mountain was beautiful at every instant, shaped like a bird flying over its nest, and where the people I saw transmitted something divine through their very existence.

But when someone spoke to me, I soon felt overwhelmed and listened without listening, tired of having to think about each sentence said; with one word I would run off, or remain there absently, isolated by the curtain of my thoughts.

But when I couldn’t find the words to slip away, or a view to distract me, then, unmoving and subdued, I would summon up my forces to hide my boredom or my secret desire to slap that person in the face and depart.

And if, when with friends, I grew excited by the sight of some sunflowers or an ash tree, or if I discovered the shadow of a cloud cast onto the mountain, or if, gazing at a chestnut tree, I saw a drop of water on a slanted leaf sliding from center to edge, slowly descending as if on a slope, I would realize, thanks to the near deafness with which they listened to me, that I was moved by things that did not interest them, and that my words to them made a pointless journey, as pointless as an elevator in which someone has pressed all the buttons so that it stops at every floor and opens its doors without anyone ever getting on or off.

Whenever my parents left on a trip I’d do nothing but wait for their return. In vain I told myself they would be back in a few days, I felt their absence in my very being, in the house and in the village, and in my brother’s face, as if they were never going to come home. Every act of mine was carried out without them. Every thought missed them. I played knowing they weren’t around. I wandered the streets with a sense of all that was lacking. And if I went with my friends to the orchards to pick fruit or throw stones at lizards, from the hill, amidst the trees, I would hear the midday train and the afternoon train, telling me that today was Wednesday and that my parents would not return until Saturday, that there were still Thursday and Friday to get through.

Like a sleeper who suddenly feels the void surrounding him and instinctively throws himself towards the edge of the bed to hold on and not fall out, I trusted in the movement that from darkness and solitude made its way towards my father, for he circumscribed my body like the black line that outlines a colored-in figure in a drawing, and nothing could happen to me while I was magically surrounded by him. Due to this attachment, I despaired each time he went away and believed I’d never see him again.

The night was full of noises. I could hear the silence of the corridors, the moisture on the walls, the roof’s decrepitude, women’s moans traveling through the air, foxes springing from the rooftops onto the plants below, yelping, and the barking of dogs, which would start far off, then be taken up by dogs nearer by. The darkness weighed down on me as if it were physical. I had to thrust aside the shadows to move. And if I felt oppressed and wanted to turn on the light, I had to push away the night as though heaving a great stone.

I’d pluck leaves from the trees or collect them from the ground; some were still swollen with rain, others perforated by insects; some were like green stars in a puddle and others had withered, their edges ochre like wounds. Somehow, these leaves let me bring the entire tree indoors, as their forms stood for the tree and one leaf was enough to recall it, and all of a sudden a miniature oak was there in the palm of my hand.

Some were the greenish-red of an apple, others the color of lemon. From the branches they would stretch out their rhythmic hands towards me, their weight pushed forwards by the air. During my walks I would visit a certain linden tree, observing it from afar and then from up close; it was my linden, the tree that resembled me in form, in character, in desire.

There were days when, to no matter what, I would answer no. My being would seal up and an indescribable weariness burdened my movements. Walking tired me. Spending time with friends. Hearing them. Seeing them. Eating. Following my parents’ orders. Going. Coming. I would remain in my room, lying in bed, watching the sun come in through the open door or, when a cloud covered it, the wall cast in shadow. I looked at the furniture, knots in the wood, splinters. Out in the corridor I could hear my mother talking to a woman who’d come to see her, or my father passing by.

At night, lights out, I could feel my soul possessed of a flexibility that could either fill space with its expansiveness or else concentrate itself into one small point; able, like some kind of spiritual entity, to go wherever it pleased or visit the person of whom it was thinking, without moving, without making a sound, simply out of desire.

Sometimes, drawn by my parents’ laughter, I would go to them with open arms, but an unexpected ill humor would greet me, and instead of a kind word an order to leave at once would be issued in a harsh voice … And I’d withdraw without understanding why this wrath was concealed within their apparent joy, as confused as someone who attends a celebration in a country whose language he barely understands, and thinks he hears the revelers using words that in reality they’re not using, and sees in their faces a contentment which is not really there, and when he thinks that the spectacle has ended, he goes up to congratulate one of the most enthusiastic-looking participants, only to discover that that beaming face isn’t laughing but is, instead, irate, and, banished with a shout and a shove, he realizes that what he thought was a party was in reality a brawl.

Alone in my room, I would put off turning on the light to follow on the wall the final moments of the day, which for me were like the first rays of night’s dawn.

I followed the falling of dusk on the floor, like the dampness on cardboard that has gotten wet and darkens as it grows wetter. The sun reverberated in some of the windowpanes, lending the air an orange tonality while gilding the roof of a house, and cast the shadow of a pigeon onto a wall.

Within the room, countless eyes were closing and the light’s brightness was becoming more ethereal, depending on the view from the window. White objects were clothed in a darkness that seemed to emanate from within, as they shrank in size like melting ice.

A visual silence dominated the horizon and, in the room, a geometric quietude. The falling dusk welded distances, blended differences, blurred the borders of objects, joined heaven and earth. Remoteness was abolished through the act of erasure.

Ill in bed, I listened to voices on the street, trying to recognize among them the voice of a friend, but in the din the shouts became indistinct and I couldn’t tell whether it was a woman or a child calling or speaking. They all seemed to come from the same place, questioning and answering among themselves, although perhaps the voices were in reality far from one another and did not seek each other out, and it was only due to the silence of my room that my ears united them and gave them a conversation in space; on the wall, meanwhile, the light darkened or brightened depending on the movement of the clouds outside, veiling and unveiling the sun.

And so I would remain, hearing and watching the hours pass by in all their heaviness and penumbra, feeling a loneliness not just in time but in space, and a certain inexistence … Until I’d finally rise from bed, weary of showing misfortune on my face and, crossing the corridor, I would go outside, in defiance of my despondency and unease.

There were days when the day itself was one incessant and varying prohibition, imparted in my mother’s voice that followed me everywhere, like someone maintaining control from afar with the help of a magic leash: “Don’t drink that water.” “Don’t eat from that plate.” “Don’t throw away that peel.” “Don’t cut those flowers.” “Don’t go outside.”

At the market with her, seeing fruits proffer their flavors to the eye — as if through their shapes and hues they could express their singularity in the universe — sensing the fleshy pulp beneath the texture of their peels and, having decided on a plum, my eyes would then wander towards a peach, or discover a tangerine, slipping from one fruit to the next as if on a scale of colors and flavors that attracted me through sight, smell, and touch at the same time, not knowing to which of the three impulses to surrender; no matter which fruit I ultimately chose, it would embody all fruits at once.

Like a child who goes about in the company of old folks, quickening his step at every moment, displaying his impatience through his hurried gait, I would go for walks with my grandmother: imagining monkeys suspended from branches by their tails and parrots that climb around hanging by their beaks, watching sparrows hopping along, pecking at crumbs or digging in the dust for insects.

We would pass beneath the shadow of a great oak, cross a dusty bridge that looked as if it had been abandoned no sooner than it was built. Our dog chased pigeons, who took flight as soon as they felt his breath. A mockingbird perched on a branch conveyed, through his very being, an entire region, climate, and time.

Before long my grandmother would grow tired and we’d sit down on a rock that commanded a view of the village. Immersing herself in its landscape, she would say, “Those houses didn’t used to be there; the highway used to run elsewhere; there didn’t used to be a train; there were only bandits and a few families; I can scarcely remember — I must have been eight or so — your father hadn’t yet arrived at our village; your mother still hadn’t been born; it was the year eighteen hundred and something; before the Revolution, before you were born; that bridge you see down there, those stores didn’t used to be there …”

As her voice dropped it confined her within herself, until the memories carried her so far back that she became inaudible.

To me she looked wrinkled, old, dried up, leaning on her cane, entangled in a thicket of faces and events from which she could not extricate herself. Then abruptly she would stop talking and rise from her spot, and we’d resume our walk while her lips continued to move as if telling herself something, or she’d start adding up a sum in which all the numbers got jumbled; growing paler and dustier, her legs more bent than before as if at any moment she might sit down on the air, but no, she didn’t sit down, she was only very slow.

I’d kick along a stone with my foot, listening to it bounce off the cobbles. But just when my feet found a pace, we’d stop again for another rest, and looking as if each wrinkle stood for a different memory, my grandmother seemed to bid me have patience.

All of a sudden I would catch her watching me, with thoughtful eyes that tried to take me in before aligning me with the image in the photo she held in her hand; but, hesitating, the sparkle in her gaze flitted elsewhere … before quickly returning to fix on my face, finding in my features the ancestral traces of my aunt Hermione in the photo.

I could feel her, my aunt Hermione, and my mother and father and my paternal grandparents, all harmonized within my very being; and I thought about her own parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, and of the endless line of the dead that lay behind her and me, and I accepted them all in my face and body, in my thoughts and words, without resistance and with love.

Then she stood up, trembling on her cane as if about to lose her balance, and walking as fast as her legs allowed sought the shadows cast by trees and the shady side of the street.

On Sundays the campesinos would descend into the village with their wives and children, with wheat and corn to sell. Wild cherries and prickly pears, sapodillas and peaches, were paraded through the streets in baskets and boxes. Sitting amidst the hats in my father’s store, I would observe the people who came in to buy clothes.

During the rainy season clouds often appeared out of nowhere and rapidly darkened the sky and a sudden downpour would drive the crowd from the street into our store. Lightning bolts blanched the day, thunder drummed on the mountain. In hurried threads the rain dispersed a delicious-smelling fog. Then, a few minutes later, the sun came out again, the village floating on the fragrances of earth and wet plants.

Some of the campesinos who’d congregated in our store bore the essence of the region in their faces; gathered there, watching the rain fall, they seemed possessed by a pluvial individuality that lent them an intimate weightlessness, as they observed the sacred falling of water with millenary resignation.

Among them were girls whose complexions looked scraped from the earth, watching furtively as if they were their own shadows.

My mother believed our house was full of treasures, buried by the bootleggers who once lived there or by their predecessors, who inhabited it during the Revolution. The house was altered when my father remodeled it; what was once the kitchen was now a corridor, and there was a bedroom where parapets had stood in case the house came under attack. After weighing rumors against her own fantasies, my mother would undertake the excavation of a room or the corridor, sending a workman down several meters below ground.

Souls in torment would appear to the maids and disclose the location of the treasure, or else snatch them from bed in the middle of the night and drag them along the ground before depositing them at the exact site. Treasure seekers arrived from Mexico City with their instruments for detecting hidden objects, and for several days many large holes were dug in all the rooms.

Only once did my mother own a house with a treasure, but that treasure was discovered by others. My father had rented this house to three poor, spinsterly sisters; each night, the eldest, the ugliest and skinniest of the three, was pulled out of bed by the hair and pinned to a dead sapodilla tree. This gave them the idea — the only one they ever had in their lives — of digging up the ground around the sapodilla, and there they found three coffins brimming with coins, which my mother later assumed were of gold. But since the house belonged to us, the three sisters left the village at the crack of dawn with two donkeys loaded down with sacks, heading for an unknown destination … My father discovered the excavation from the holes in the ground where the coffins had been, and realized there’d been coffins from the bits of old wood mingled with the earth heaped next to the tree. My mother continued to buy houses, which she would then demolish, digging beneath walls and tearing up foundations, but all her hunches came to naught.

There were days when the table was being eaten away by woodworm, our clothes by moths, our bread by mold.

Plates were chipped, the door unhinged, the chicken plucked and quartered.

A neckless bottle and a broken chair would appear in the poultry yard, and the fins of a recently eaten fish emerged from the garbage can like a sign.

The entire house was like a window without panes, and man in time, like sugar dissolving in water.

The days extracted shadows, scraps, and splinters from things, exposing their hollows and their chaff; they wrinkled faces and devoured animals.

Bloodied butchers would walk past the store leading cows to the slaughterhouse, where in one blow they’d be killed.

Drawn by the blood and warm flesh, dogs ran after them barking.

The bellowing of cows filled the streets as they refused to move along.

But after a while, all that remained where they’d been was the quiet of the afternoon.

The next day the executioners would pass by again, this time in the direction of the butcher shops, accompanied by assistants carrying large slabs of meat on their backs and donkeys laden with chines and legs.

Whenever my father brought me to Mexico City I was afraid of getting lost. The crowds seemed to press forward to trample me, and the whirlpool of people created a confusion into which I strayed.

Worst of all, there might be a very wicked person who would kidnap me and keep me from ever seeing my parents again, forcing me to beg on the streets.

That’s why my father carried me on his shoulders, from the warehouse to the toy store, from the hotel to the movie theater.

Within me there existed another, a boy who would enjoy getting lost, who yearned to live in a dark place with no outdoors or suffering, who was drawn to the crowd, desiring to lose himself among the faces and feet, in order to no longer be me.

But I loved my father, and nothing would’ve consoled me had I stopped seeing him; and so it was he carried me on his shoulders.

Upon hearing the sound of my cousin roller-skating down the corridor, I’d run to see her.

She skated clumsily, opening and closing her legs too much and in danger of falling each time she picked up speed; and in an effort to keep her balance she’d stop short, or one foot would go in the wrong direction. Yet the movement of her hands, which she raised as if fending off a danger from above, and her closed eyes as if to avoid witnessing the disastrous end of her sprint — she seemed always on the verge of something happening to her, though nothing ever would — revealed an inner rhythm expressed in movements and gestures in which I divined a certain placidity that calmed me, just by watching her. It was a placidity undercut only by a fine line of impudence in blossom, which lay upon her lips like a crooked grin, betraying on her face a habit of spending too much time in the bathroom touching herself in private.

It was hard to escape when my brother chased me. He could run twice as fast as I could, and hit harder as well.

In the house, down the corridor, through the garden, from room to room, he ran after me and I could never find a place to hide.

I would search for my father (who wasn’t there), and my mother (who had gone out), and the maid (who never defended me), until I’d find myself pinned against the wall, forced to confront him, and the tussle would make me cry.

Eventually my father would arrive (always after my brother had hit me) and scold us both, and I never understood how I was guilty, since all I had done was receive the blows. But I was guilty, he said, of provoking them, or of putting myself in the way of being hit.

On the first Sunday of October the mummers would appear in the streets, begging for money at shops and houses; masked and dressed as women, they danced in worn sandals around the villagers and made grotesque movements with their bodies. Even before they reached our house we heard their drumming, their laughter, their flutes. They circled around my father, who’d give them coins and cigarettes, and made fun of me, waving their hands around their masks, which I believed were the actual faces of pigs, hags, and devils.

Children ran away at the sight of the mummers stomping their feet and groaning. My father would reassure me, pointing out that those hideous crones were really men in disguise.

The town fair would take place a few days later. The merry-go-round, the hoopla, the Caterpillar. Men set up games, heavily made-up women arrived. People played cards and threw dice. Outside the tents, the eagle woman and the snake woman were advertised.

Love songs drifted out of speakers everywhere, and at night a firework bull, carried on a mummer’s back, would be set alight, launching blue balls into the air, until the bull, in a burst of pure light, burned away entirely, leaving a gunpowdery-smelling frame on the mummer’s back.

I detested my cousin who visited us from Morelia and danced La Bamba. From the very first night, his father would make him dance in the corridor.

But I’d never play with him. He went around with my friends during his stay in Contepec. What’s more, he had a reputation as a crybaby, after once getting into a fight and having his nose punched, which resulted in blood and tears. He was always with his father, or with my cousin, my aunt from El Oro’s daughter, whose too-short dress showed off her growing thighs; my brother used to seat her on his lap and stroke her breasts.

I had a great urge to set off firecrackers in my cousin’s ears. But my parents laughed each time he danced, and the adults claimed he was very intelligent.

I preferred my female cousin, who would share the bedroom with my brother, my cousin, and me, and though I felt jealous at night when she and my brother kissed when I wanted to kiss her myself, I went to sleep without being able to prevent it.

With her we climbed to the school to view the village from above. Or when my brother wasn’t around we played married couples in the garden, because when he was home he would take her to his room to play alone. And if my male cousin ever tried to interfere, my brother punched him in the stomach and made him cry.

Like one who dreams the air around him has turned to stone and wakes up to find that it’s only his hard pillow, sometimes the oppressive darkness would produce a feeling of death in my body, which would then vanish with the magical act of turning on the light.

Perhaps because of this fear of dying I never liked nights that were too dark, nor did I like it when my room was too white, for the painted door reminded me of the coffins in which children were buried.

The funeral processions passed by our house, and all of a sudden in the morning the bells would start tolling and a devastating cry, an exaggerated shriek, would cross the sunlit streets making the silence resound, as when a pistol is shot into the clearest blue sky. Shortly afterwards a woman in black would appear on the corner, weeping. Behind her several men carried the coffin, dressed as if they’d been asked to help on the spur of the moment while working in the fields. And alongside them other women, peasants as well, accompanied the grieving woman in clothing, gait, and lamentations.

In the rear, lagging behind as though headed elsewhere, to judge from the distance between them and the procession, came the children, whose expressions suggested they were more interested in playing than in this march, bearing their imposed mourning like people who have recently been wounded in the face and whose features have yet to adjust to the scar, presenting two expressions at once.

The poverty of their clothes and the archaic quality of their features lent these campesinos an aura of solitude and abandon, as if they were participating in a rite taking place in some remote setting and were only present in time through their suffering.

Chapter 2

BY MY SIDE, sitting at our desk, was Quedito, who smelled bad and whose face looked swollen.

Since he was right next to me I couldn’t resist calling him Quedito, but he hit my arm in annoyance whenever I did.

Using his nickname meant touching a sore that others touched with impunity, even for fun. But whenever I said it, he turned on me as though I stood for everybody.

I had no idea why they called him that, if it was on account of some personality trait or because of something that had happened to him, or simply because the nickname already existed and someone had to use it. But maybe they called him Quedito because he was always silent in class, scarcely moving, elbows on notebook, pencil in hand, eyes open yet absent.

He was two years older than me, taller, and stronger. He lived near the mountain, and brought peaches to school that he ate without sharing during recess, moving away from us to do so. He came to class before the other pupils and sat at the top of the long flight of stairs, his gaze meandering down the steps, ignoring the kids who climbed them, as if lost in thought. Meanwhile the students passed by repeating, “Quedito” … “Quedito” … “Quedito” …

Two by two we sat on the benches, in a classroom adorned with nothing but a blackboard and a long outdated calendar forgotten on the wall. From the center of the ceiling dangled wires with bulbs on which flies had dried.

Our gazes were fixed on our teacher, seated at her desk, though mine nearly always strayed out the window or else down below, towards the village.

The school stood atop a hill that resembled a wrinkled breast. To reach it you had to climb a lengthy stairway, or else walk up a street bordering ravines. It was said that our school had been built during the Revolution, and it commanded a view of the village, its clusters of houses, and, farther in the distance, the railway station, the cemetery, and the highway.

During recess we played among the rocks that had been in the playground since before the school was built. We would sit on top of them while Quedito, dull and colorless, went on and on, like a lie machine: “My uncle has a hook for catching whales …; he owns a ranch with five thousand hens …; he has a horse as large as a house …; he owns a lion that once ate a crocodile …” He stared at my clothes, while he himself swam in his brother’s enormous trousers and a shirt whose sleeves flopped over his hands each time he tried to gesticulate. A nocturnal anguish had settled into his features, into his sagging eyelids, so that even when his voice showed enthusiasm, his expression made him seem about to cry. Every now and then a sparrow stirred up some dust with its wings a few steps away; Quedito would fling a stone at it with all his might, but always miss.

Recess would be ending on an unhappy note. To shake off the suffocating feeling brought on by Quedito, I would run towards Juan and Arturo the moment I saw them.

One Monday Juan and Arturo came across our teacher’s panties on a rock and drops of blood on the ground. Juan told me that on Sunday afternoon she had come to the school with three of the older boys and that in one of the classrooms, amid the desks, they had beaten and raped her, tearing her stockings and dress, and that Ricardo el Negro had been one of them. But when I searched for traces of the rape and beating in my teacher’s face, I found her no different from before, apart from a bandage on her chin and a blemish on her neck. She spoke in the same manner, walked and moved in the same way, and her face bore no traces of the blows she had supposedly received. That said, when I looked at her it was as if her whole being were sullied, and on her painted lips, half open and moist with saliva, I sensed an absence of shame that troubled me. And when I’d hear her described as very thin, I’d translate the word into tubercular. And when I’d bump into her brothers on the street, I’d wonder what it must be like to have a prostitute for a sister.

Driven by these thoughts, Juan and I went one night at around eight to spy on her in the dark portico near her house, where she would rendezvous with her boyfriend. We approached stealthily, hugging the wall without casting shadows, and when we peeked in we saw a couple embraced in a kiss. And then we ran away.

Ricardo el Negro, the illegitimate son of a fishwife, would have been around fifteen. He stole chickens and fruit from the orchards and for a tip would do anyone’s odd chores. Though enrolled in school he played truant, spying on the women bathing at the stream, first from the waist up, then from the waist down. The toughs in town communicated with him by “frogs” (a punch in the arm) and by slapping his back so it burned. Among his nicknames were Son of a Bitch, Sooty, Asshole, and Jerk, and many others that were invented and forgotten the same day. A bastard with no visible father, he would sit by the pots of hominy stew that his mother sold each Sunday and gaze hungrily at the food being ladled into the bowls and then eaten by customers. During the week, he and my brother visited the baths in Tepetongo, a few kilometers from Contepec, losing themselves for hours on the plains and in the hills, or returning late at night, drunk, after spending the day playing poker, or suddenly plunging into the swimming pool where all the women swam naked. With his single pair of shoes, once black and now muddy and gray, and the trousers and the shirt my brother had given him, which he took off only when they had to be washed, spending that day at home naked in the kitchen with his mother, who was cooking the stew for Sunday, he laughed when outside the older kids called him “Ugly”; and when my parents weren’t home he came to the house with my brother and chased the maids, throwing them to the ground amid laughter and threats, until they got up and ran away, panting and disheveled, cursing him because he’d pulled their hair, hurt one of their breasts, or torn a dress.

“Go home,” my mother would say to me at the store, “because Ricardo el Negro is on his way, and I want you to keep an eye on him.” And to my father she’d add, “Lola’s brother came to complain because each time Ricardo el Negro goes to our house he pesters her.”

My father, concerned, would answer, “Let him stay here, I’ll go.”

And he’d go home to find Ricardo in the kitchen, sitting with Lola on his lap, her tits in his hands.

Every now and then at our store a drunkard pulled out a gun, pointed it at my father, and insulted the customers who were buying things.

The sons-of-bitches flew right and left, verbal vomit the drunken man couldn’t keep in, spilling from his insides in a drool of clumsily articulated sounds. His finger on the trigger, he aimed at one person and then another, advertising his presence in an angry voice, his face twisted with hate, dragging himself over to my father, who said, “Go home, you’re drunk.” But the fury of his monologue unabated, the drunkard flung a bottle to the floor, dashing it to pieces, like a sentence exploding in everyone’s face. After a few minutes, however, he tucked his gun under his belt, asked for a pack of cigarettes on credit and a loan of ten pesos, and left.

And when foulmouthed boys at school engaged in a dialogue of obscenities during recess, in the form of off-color puns or insults all round, I could feel the filth from their tongues besmirching every limb, word, or person they mentioned.

It was almost physically impossible for me to say bad words; my tongue refused to pronounce them, and to do so seemed as violent an act as smashing a glass in someone’s face, for it meant breaking an object at the same time as hurting a person, and soiling myself in the process. But the truth was, I had no talent for them, and I’d forget the words as soon as I heard them or, better said, I’d bury them within my very depths as if they were slimy leviathans. As for my father, at the height of his wrath he could barely bring himself to utter a “damn.”

The cemetery lay beside a field belonging to my father. Its whitewashed wall, built from alternating stone and brick, rose around it like a supernatural barrier separating life from death.

Whenever I visited the field, walking among the magueys, I would think about my dead sisters and about the other dead. I wondered how many souls of the deceased, from all ages and all countries, there would be now, and whether there were more dead souls than living people. I thought I could see my sisters, who died before I was born, up in the sky. And so strongly did I feel their existence, spread across the blue like a spiritual ether, that sometimes a word or gesture of mine seemed inspired by them. I never knew them; I’d only seen them in photos, tiny and naked, a few weeks before their deaths, still looking as if they’d just arrived from elsewhere, radiating a strange happiness. My parents kept these photographs alongside their dresses and knitted booties, and when we had guests over they would bring them out, to illustrate the tale of the dead daughters. Alone in my room, I sometimes thought I could sense their presence, without fear and with love, for they were my sisters. And on overcast afternoons, when melancholy led me to sit beneath the fig tree or wander about the poultry yard, something in me began to sense they were nearby. But I couldn’t see them, for if someone sees a dead person he can no longer live in the world of men; he has entered into the other one, the world of ghosts. Yet every man carries his ghost, latent, within him.

The baa of the lamb tied to a pole in the backyard filled me with the queasiness triggered by the sight of animals one knows are awaiting their death. Still very young, with budding horns, he ran around the pole, or stood still, staring at the ground with unseeing eyes; every now and then he emitted a prolonged baa, whose very sound was painful to me. When I heard it I went to hug him, seized by an immense affection brought on by his body and his bleat. But I’d stop and stand by his side, running my hand through his wool and over his hard head. He seemed to be addressing me with his baas, and didn’t appear to eat anything, for the same withered grass rose between his feet.

For a few days, when I visited the backyard I knew he would be there, standing beneath the sun that warmed his wool, amid the sparse shadows of the pear and fig trees.

Until one morning he wasn’t there, and I found out that a butcher had taken him away to turn him into barbacoa for a luncheon we were having the following day.

I went to my father, wanting him to intercede on the lamb’s behalf, but was told he’d been slaughtered at dawn.

And so they served him to us, at a meal my parents hosted for a storekeeper visiting from Mexico City. With a chunk of leg on my plate, I suffered to see the lamb I’d been so fond of changed into steamed meat, hearing deep down inside me his heartbreaking baa as a kind of reproach.

This visual grieving for his death prevented me from taking a single bite, as I sensed his body in its mutilated form and I was filled with a growing desire to piece him together again and return him to the pasture to graze. The general enjoyment and the maids’ sporadic laughter as they served him up, the methodical words of the storekeeper, who referred to him as food and went on about other ways to cook him — all this offended me.

I couldn’t help getting the shivers when I felt tempted to eat the lamb I’d loved alive, my hunger entangled with his smell, and was on the verge of eating him along with the others; then I reminded myself that for me he was not only a piece of meat on a plate but also his eyes, his baas, his existence.

So I said I didn’t feel well and would only have soup, cheese, and a glass of orange juice, overwhelmed by the sadness that the death of animals aroused in me, experiencing the same disquiet as whenever I saw the maid snapping the neck of a rabbit or chicken as if she were simply twisting a rope, then placing it, inert, on the table, almost immediately after the final spasm, to be later skinned or plucked.

The freeloaders would show up while we were eating. After learning from the butcher that there was mole in the house, my uncle Carlos would appear as though drawn by the smell of the food, asking for me since he was on the outs with my parents, with whom he no longer spoke and would greet with a stiff nod of the head. He’d sit down at the table, listening attentively to the conversation, waited on by a maid. Almost immediately afterwards, don Raimundo would arrive. Waddling in like a fat pigeon, he would thrust his plump arms behind him as if they were plucked wings. He was the village tax collector, and diving into the food, he didn’t appear to see any of us watching him, nor hear us talking, so absorbed was he in stuffing himself. Don Raimundo and my uncle Carlos were not on speaking terms either; I think they even pretended not to notice each other’s presence at the table. Yet my uncle, ill-tempered and sarcastic and, at the end of the day, knowing he was my mother’s cousin, would sometimes fling a mocking remark in don Raimundo’s direction, such as, “Slow down, the mole isn’t going to run away,” or else, “Sit down and take a rest,” don Raimundo of course already being seated.

But my uncle spent fifty weeks a year being angry at my parents, and only two, spread out in days over the months, on good terms with them. My parents could never figure out, however, despite all their guessing, why he was angry; they could only assume that the sole and constant reason might be envy, for it profoundly disturbed him that my father was better off than he was. On the other hand, he was accustomed to carrying his envy around as if it were a chronic disease from which deep down he derived a certain pleasure, or using it as a justification for his intolerably bad manners. Nevertheless, each time there was a special occasion at home, he would appear uninvited, like a dog with his tail between his legs, as they say. But even more than my uncle Carlos it was don Raimundo who went after food like a dog regardless of who was providing it, be they friends or enemies, ignoring rebukes and insinuations. He barged in on any meal and sat himself down among the unwelcoming diners, digging his hands into whatever he could, literally grabbing everything within reach. Sometimes he was thrown out of a house with shoves and insults by a host who was either irascible or too poor to seat an undesirable guest among his family members. Short and tubby, he seemed to flaunt in his fleshy face his ravenous stomach and buttocks.

My father was always patient with Raimundo because he’d help him arrange tax matters and documents for the store, in exchange for five free meals a year and clothing he’d ask for on credit but never pay for. Tipped off by the butcher, our maid’s boyfriend, Raimundo would arrive and from the dining room door ask, “Am I disturbing you, sir …? I’ve just come to tell you that your papers are ready,” etc. He then drew up a chair and sat down with us, talking incessantly. Only once he was certain of a chicken breast on his plate would he shut up.

My uncle never talked. He ate in silence, as if angry, repeatedly scratching his arms. He would eat and leave, with never a thank-you or a goodbye. His whole attitude, from the very start, seemed like an insult. He dealt in animals: donkeys, cows, and horses, but just to compete with my father, he opened a clothing store one day and began selling seeds, though he spent more time gossiping than making money. And once he’d turned into a rival, he quickened his step each time he passed our store to avoid saying hello. And he’d walk past several times a day to show how angry he was. Whenever she saw him my mother would say to my father, “There goes Carlos, snorting with rage.”

Sebastián, my mother’s brother, lived in Mexico City. He was married to a woman ten years older than him, which didn’t prevent him from having fun with boys; he would put them to work in his studio as assistants in making dolls, wooden toys, and Sacred Hearts of Jesus; amid the Virgins of Guadalupe he’d hug them and kiss them on the mouth.

His house smelled of varnish, wood and paint; his suit, hands and face were always stained. Once a year he would come to Contepec for a week, at Christmas. And whenever he was with my mother, the main topic was always their father, whom he attacked as if seized by a cyclical rancor each time the conversation turned to certain people or included certain words.

“Why should I call father a man who would only lift his leg to pee?” he would ask with rage. “The only things I ever got from that old fool were blows and disdain.” He would grow more violent at my mother’s protests: “Why should I thank that scoundrel, that jackass? No!”

My mother had a photograph of my uncle at age fifteen, with a head full of curls and lips painted in a heart shape, freshly arrived in Mexico City to work as apprentice to a doll maker. His sweater bore a crest with the initials R.S.Z. On the back of the photo was the name Rosaura Sebastián Z.… Seeing him like that, you would have thought he was a young woman in drag.

Before long, my uncle had set up his business and married Marta, the young lady who had come to buy the painting The Death of Manolete, copied from a calendar. She had fallen in love with Sebastián, finding him both artistic and refined. But the day after the wedding, my uncle vanished from morning to night with nothing more than an “I’ll be right back,” the beginning of a long series of escapades that she forgave on account of his infantile and apathetic nature.

Perhaps as a bulwark against loneliness, my aunt found a little old lady, a friend of her mother’s, to live with them. The woman had been a nun who’d been expelled from her convent for being too obsessive. Old people’s homes wouldn’t have her either and kicked her out after a few months because she spent all day in the bathroom. This virgin was given the nickname “The Handwasher” because of her mania for washing her hands. She saw germs everywhere: in greetings, slight grazes, dust, furniture, in the very air. Over the years she reached the point of washing her clothes while wearing them, and ironing them dry while they were on her, several times an hour. She was more hunched over each time my father brought me to Mexico City, and my uncle would point at her and say, “Here before us is a complete question mark.”

As soon as he woke up my uncle would go out, faithfully telling his wife he’d be back in five minutes, and not come home until nighttime. He had breakfast, lunch, and dinner in eateries and restaurants, always alone and always frugal, pretending to be poor, dressed in secondhand suits his relatives sold to him and he paid for in installments. He’d fish out the money from among torn bits of newspaper and old shopping receipts, the peso bills folded together with the thousand-peso ones. He frequented warehouses and spent hours talking about nonexistent shops so they’d lower the price on fabrics, which he then bought and stored in a closet, forgetting about them, or at least seeming to. If he went to visit someone and took a liking to an object in the house, he persisted, through pleas and promises, in trying to obtain it, and if the lady in question (for he only visited ladies) gave in, he took it home and put it in his closet and never took it out again. He always arrived late to appointments, or not at all. And if he made plans to travel with someone to another city, promising to take the train at a certain hour, he simply didn’t show up, knowing full well, from the moment he made the plan days beforehand, that he had no intention of traveling. And whenever he rode in a crowded bus with my aunt and a seat became free, he seized it and left her standing. And if something happened on the street and a person threatened him with violence, he became hysterical and screamed out, “Marti, Marti, Marti … save me from this lunatic!” If at night he felt cold as they walked around downtown, he asked my aunt for her sweater and scarf, put them on, and then took her arm.

Sick peasants would come to our house, stricken with rheumatism, kidney trouble, old age. The skin stretched over their bones looked tanned by misery. Pain seemed frozen into the wretchedness on their faces. They sat on a bench in the main square, beneath the shade of a tree, and waited for my father to administer medicine. Patiently alert, they watched dusk fall over the streets with wide eyes. They’d sit there for hours, with never a word to anyone that they had come to see him. They might even notice when he arrived and was about to leave without speaking to him … And at times, when I was with my father, we heard a hesitant voice calling out behind us, “Señor Nicias?… Señor Nicias?”

And my father would come to a halt. Knowing well what this was about, he walked towards the man who’d called to him, who was propped up by his wife and in too much pain to move.

“What’s the matter with you?” my father asked.

“The sickness, sir, it won’t leave me alone.”

And during a dialogue of few words and many silences, I observed my father and the man watching each other, as if reading each other’s thoughts on their faces.

Until all of a sudden the man burst into tears, saying that his kidneys were killing him and, pouting like a child, that he was very hungry.

On days my father didn’t show up some of the peasants waited until night, taking short walks around the square or going to the market to buy fruit. The darkness slowly engulfed them, turning them and the trees black. Their children played haunted house with the village children, running between the flower beds, emitting feeble cries, stumbling frequently from weakness.

They ran barefoot, in torn and patched trousers, stepping on the grass, clowning around and bumping into passersby.

Often a dog that had come to town with one of the families was lying nearby, and his paws would tremble as he tried to stand up and stretch, as though his legs were too frail to support him.

When she heard that the peasants were waiting for my father, my mother would go tell them the approximate time he was expected back from his trip. But it made no difference whether she told them three in the afternoon or nine at night, it did not seem to diminish their resolve to wait for him, although one could detect weariness and sorrow in their eyes.

Next to the market, in a dusty lot, a family of circus people had set up a tent for the fair in October. Among the advertised attractions was the man without arms, “fallen to earth one moonless night from a spaceship,” according to the handwritten paper sign hanging over his head. The man without arms, the circus barker cried, could light a cigarette, fry an egg, untie a knot, and play cards with his feet. These were the feats he performed during the show, sitting in the center of the ring, dressed in black like a priest, his cheeks painted like a clown’s. He would go through his act in silence, exasperating the audience with his slowness, spending too long opening a package or uncorking a bottle of wine, investing too many minutes in the eating of an egg with a knife and fork. But just as the audience began to display traces of boredom, murmuring among themselves or shifting in their seats, the man without arms would lift himself abruptly from the floor, thrusting himself upwards like a rag doll and disappear offstage in a dance.

Once the performance had drawn to a close amid whistles and applause, two sibling trapeze artists would appear, a man and woman in bathing suits, announced by a loudspeaker. Almost immediately afterwards they were joined by a dwarf, whose nose was painted red like a tomato. The dwarf seemed to have normal proportions when seated, but the moment he stood up you noticed his lower limbs were extremely short.

Maize the dwarf, dressed in blue, wearing clown shoes, and always ceremonious, would imitate his companions, falling repeatedly from his trapeze, half a meter high. His charm stole the show and few paid attention to the real trapezists.

The female trapeze artist, whose legs were brown and chunky, reappeared, this time in a sequined suit, and walked the wire. She teetered clumsily to keep her balance while the man without arms, who was her uncle, watched from below.

The teenage boys would follow her legs rather than the act, and when she bent over, in her generous brassiere and her tight panties, there was something almost obscene in her manner.

My brother had fallen in love with her, and wanted to run away with her once the circus left town. In the meantime, he attended every show.

But my father was aware of his intentions, and asked me to keep an eye on him.

I’d follow him down the streets and through the rooms of our house, listening as he spoke to himself, watching him leaning against the fig tree as he stared at his own shadow for hours.

He seemed not to see or hear me. And if he did, it was with the blindness and deafness of someone who is near us but whose thoughts are far away.

After the show I would find him with the trapeze artist in the darkness of a portico on the edge of town, clinging to her as if their bodies were one. I could hear, while I waited, the coyotes howling in the hills.

After a while of being glued to each other, they would part ways and take different streets.

And he would have left the village with her had he not seen her entering the cacique’s house one Saturday night after they’d said goodbye, staying inside with him and not coming out the entire time we waited outside.

The cacique had killed Quedito’s father. He’d taken him by surprise as he climbed the stairs leading up to the school to fetch his son. The cacique had shot him in the back from down below, halting him midway between two steps, the bullets thrusting his body upwards for a moment before he tumbled down, in a matter of seconds, the stairs that had taken him ten minutes to climb.

We were in class at the time and heard the shots. One. Two. Three. While our teacher talked on about the Sierra Madre …

Quedito, seated next to me, barely stirred when he heard the gunshots, unaware they were connected to his life.

Then we heard the voices of the younger pupils, whose classroom windows overlooked the stairs

“The cacique has killed Don Manuel,” someone shouted.

And we saw several people tearing through the yard.

Our teacher forbade us to leave the classroom. She ordered us to remain quietly seated. None of us could resist looking over at Quedito, who sat next to me as if frozen, with his mouth open.

“Come,” the teacher said to him. “Let’s go see what’s happening.”

He didn’t move.

So she took him by the arm and insisted. “Stand up. I’ll take you home.”

And she helped him up from his chair, his legs numb, unable to take a step.

“Can’t you walk?” she asked.

Quedito didn’t answer, as if she were addressing someone else or he couldn’t understand her words.

So I said to him, “Quedito, the teacher says she’ll take you home.”

He looked at me and shrugged, and stood staring at our teacher, his face like a shattered windowpane, about to break into sobs.

“Let’s go,” she said. “Shall we go see what happened?”

At first Quedito wouldn’t budge … He then began to walk on tiptoes towards the door and as soon as he got close to it broke into a run.

The teacher ran after him, losing a shoe on the way. And we ran after her, to see Quedito rushing down the stairs four at a time, always on the verge of tumbling down, his eyes desperately searching for his father, who’d already been picked up and taken home.

One student said:

— They got him in the chest.

Another:

— In the stomach.

Another:

— In the hand.

And they’d point to the stretch of stairs Don Manuel had been mounting the moment he received the gunshots.

And one young pupil, pale with excitement, descended the stairs with his gaze.

The next day, in the square, I encountered the cacique.

Leaning against a lamppost, he straightened himself upon seeing me, staring so intently his eyes seemed to bulge with a wrath he wished to vent on me.

I stood still, not daring to walk any farther.

He had a magnetism like a serpent’s, which fascinated me, his smile contorted into a kind of evil sensuality. He had killed a man: that’s what gave him prestige.

The spilt blood could be read in his eyes like a sign, lending his spirit tension, pleasure, and guilt, somewhere between satisfaction and horror.

Bent over, as if about to pounce, he watched me closely. Maybe he took pleasure in scaring me, as he did the woman who walked past at that moment; he jumped at her with a cry, and she ran away, terrified.

He didn’t laugh. He was like a dog that barks and growls by instinct.

And thus he bared his teeth at me, and began to growl. And he held up his hands as if they were claws. He was attuned to my movements, my glances, my fears. Ready to pounce. Offering me a glimpse of the revolver tucked under his belt, over the white shirt with a black ribbon at his neck. Dressed elegantly, as if for Sunday.

In his crocodile shoes, he stood between two policemen with rifles who also watched me while they checked the side streets as if sifting the air, making sure someone they hadn’t seen wasn’t approaching unawares. Their ponchos smelled of wet wool, their hats nearly covered their foreheads. They wore new shoes, which appeared to be either too tight or not the right size, judging by the fidgety way they were standing.

It looked like the cacique had deliberately placed himself at the center of the square to attract attention, perhaps as a gesture of defiance, or to assert his solitary tyranny.

All of a sudden, as if spitting out his voice, he said to me, “Where are you going, you pip-squeak son of a bitch?”

My breath was cut short.

“Okay, now that you’ve seen me, scram. Otherwise I’ll geld you.”

And I took flight, turning to look at him, his face still contorted and unsmiling, gazing around with a crazed look, still flanked by the two police officers, who laughed, yelling threats and insults at me.

One week later, on a Wednesday afternoon, they killed him.

It was near the railway station, as he was returning to the village on horseback after having paid a visit to one of his lovers.

Riding across the plain, he’d run into a man called El Chimal, with whom he had quarreled, or thought he had quarreled, since the man was an inhabitant of the village, and the village, his enemy.

As was his custom, he started to draw his gun, albeit lazily and with scant conviction, assuming the man, since he came towards him, was going to attack. El Chimal had his gun ready beneath his poncho and was already taking aim. He shot him in the face and kept firing although the rest of the shots were lost in the air.

When the cacique fell to the ground his feet got caught in the stirrups and his horse dragged him along for fifty feet. That was how far El Chimal had to go to rip out the gold teeth and trade his donkey for the other’s chestnut horse. Then he took off.

That night soldiers from another village arrived in Contepec looking for El Chimal. But they didn’t find him. After two days they left, figuring he was gone for good, but before heading out, on orders from the governor, they galloped through the streets shooting at all the houses.

Once they’d left, the villagers threw the cacique’s body into a well and covered it with stones.

The morning they buried the cacique like that, Arturo and I went to see Juan at his house.

At the post office we saw his father hunched over a desk overflowing with papers and seals; he would hold everything close to his face to read it, as if his glasses weren’t strong enough or didn’t have prescription lenses. When we knocked on the door, Juan’s youngest sister, Anita, let us in without saying if he was home or not. We looked for him in the patio, in his room, in the kitchen. With a sleepy expression and without a word, she watched us come and go. When finally we asked her whether Juan was home, she replied in a voice scarcely audible due to shyness that he’d gone out and would be home later.

So we leaned against a column in the porch surrounding the patio and watched Anita in her yellow apron as she laid out little cups and saucers on a small table and sat an old, faded doll in a chair, oblivious to our presence, as if we were no longer there.

All of a sudden Arturo poked me with his elbow to point out that Anita, who was bending over to talk to her doll, didn’t have any panties on.

And he went over to her right away, touching her from behind with his hand. She didn’t move or say anything, only stirred a little spoon in a cup. Arturo murmured something in her ear, making her blush and stop what she was doing. He then grabbed her hand and led her to the bathroom; she followed meekly.

As they passed by he told me to keep an eye open in case someone should come. I remained there, my gaze wandering over the sunny corridor, where a solitary hen was pecking at corn or staring at the wall. They’d left the door open. Anita was on all fours with her backside in the air, while he was behind her, panting.

When he noticed me watching he said it was my turn and stood up with his trousers at his ankles like empty sacks. She looked at me with a bovine expression, waiting patiently on her knees.

I shook my head. Again I was left to keep watch in the corridor, now with two hens strutting about. He sat her on his legs and later pinned her against a wall; she followed instructions.

Finally Arturo grew tired, or bored, and came to me, saying we should go. As we went down the corridor he gave one of the hens a kick. Anita was left sitting on the toilet seat peeing, with a sad, distant look on her face, as if she didn’t realize what she’d just done with Arturo, and that we were now leaving.

Across from the post office, on a bench, an old man was singing in a shrill voice of moans and wailing:

Trees cry for rain

And mountains for wind …

Strumming at his guitar:

And so my eyes cry

For you, darling beloved.

As Arturo walked away I went up to listen to the old man, and noticed that while singing all that moved were his hands and his lips; he was sitting so stiffly, he looked sculpted.

His face red and pockmarked, he resembled an ancient idol, carved out of mud, time, and suffering:

In front of me there is an angel

Looking at me with your eyes

I want to speak but cannot,

My heart sighs.

When I thought he’d finished his song, I asked him where he came from and what he was singing but he didn’t answer or even look at me and continued:

Come see, and come see,

Come see, and we shall see

The love that we two share

Come, let us be united.

Suddenly he fell silent and began to listen alertly.

That’s when I realized he was blind.

An old woman was approaching between the plots of grass, walking so slowly she never finished arriving, so short were her steps and so frequent her stops to rest.

From up close, leaning on her cane she looked weary, poor, and troubled. She turned to me as if to speak, but it seemed her voice would never emerge as her lips fretted over the word about to be uttered.

After a while she sat down and smiled at me, displaying a lone tooth, her face now wearing a happy expression.

She told me, albeit briefly since it distressed her to speak, that they’d come to the village that morning to see a brother who was ill. They felt too tired that afternoon to return on foot to their home, which lay in another village, and would I help them with the bus fare.

So I slid my hand in my pocket, and with a quick, timid movement as if to hide from her what I was doing, I pulled out the five pesos I had. Then off they went, the old man’s shoes so worn he might as well be walking barefoot, for his feet slipped out with every step.

They headed for the market, where some people with scant cash bought a roll or an orange to stave off hunger, staring at the fruit sellers with large, exhausted eyes, or licking a banana peel to the point of transparency.

Beneath the buzzing of flies, skinny dogs lay stretched out in front of closed butcher stalls, and a poor boy had been sitting on a stone for hours.

Occasionally a woman bought tomatoes at a stand, amid the silence of the vendors, who looked half asleep in their vigil over nonexistent customers.

My aunt Inés was going deaf. They operated on her and she ended up completely deaf. When I visited her in her hospital room she read the How are you? on my lips with as much enthusiasm as if I’d brought good news regarding her health. The truth is, she looked like a survivor and reacted to any abrupt movement with alarm, as though it threatened to upset her equilibrium. She’d already acquired that expression some deaf people have, midway between anxiety and disorientation, similar to the expression of sailors who step ashore after months at sea, the isolation they endured written on their faces and patent in their very way of walking.

With her elderly body and virgin heart, she had the face of a sufferer, of a suffering bird. In company she would move her lips in silence, repeating to herself what she’d read on the lips of others.

At meals, people often forgot about her and spoke among themselves without giving her the chance to read their lips, for when she looked at them they would turn their heads away.

When my grandmother died, Aunt Inés inherited the house where she lived. Unmarried, and confined to solitude by her deafness, she spent her days with a few books, reading one after the other in turn. She only interrupted her reading to write letters to suitors in Guadalajara, San Luis Potosí, and Mérida. Yet she never met any of them, for she endlessly postponed their dates in equidistant cities where the encounters were meant to take place. She became the sempiternal “Sentimental Young Woman” or the “Disappointed Blonde,” until the letters she received weekly from the “Gentleman from the North” and the “Lonely Man from Chiapas” grew scarcer by the month until after a year or two they stopped arriving altogether.

In order to garner interest in the personals of Confidencias, she depicted herself as young and beautiful, cultured and virginal, sad and forsaken, swapping photographs from fifteen years earlier with her suitors, along with intimate stories and promises of marriage. And if she hadn’t advertised herself in a certain issue she would go out and buy it at once, anxious to be one of the first to reply to the personals.

Her correspondence was kept in a padlocked drawer so my uncles and cousins wouldn’t find the letters and read them.

She finagled money from her suitors, who were anxious to meet her. Worn down and aroused by so many letters, they pleaded for a rendezvous and sent money orders for her to travel to Tampico, a place to which at the very last minute my aunt would never go, due to fragile health or an ailing brother, postponing the trip to the following year.

Busy with her correspondence and deaf to the world, she went down the street beside noisy trucks. She read by the window, bringing the book closer and closer to her eyes, frowning if anyone she knew walked past, for she had trouble recognizing their features. A smell of dust, animals, and plants had settled in the backyard of her house. From my grandmother she’d inherited pots of geraniums, roses, and pansies, and a donkey, a goat, and a dozen hens, who’d lay their eggs in the kitchen and in the bedrooms on the beds.

The train would stop at the station, a few kilometers from Contepec. Passengers disembarked from two coaches while porters unloaded crates of oranges and sacks of flour from one of the boxcars. A mail pouch, full of letters and newspapers, was dropped between melons and bananas, and women briskly peddled their chicken mole through the railway cars. Yellow in the midday sun, a dog came running over the plain, while other canines fought over scraps of food passengers threw out the windows. A venerable ash tree served as a parasol for two old men, who witnessed in silence the activity on the train; in one of their dark, skinny hands a cigarette seemed to burn endlessly, flaring up every now and then at an occasional puff. All of a sudden, the train’s whistle and its lurching march forward brought all the activity to a halt and voices fell silent. In the landscape once again visible in the train’s wake, those of us who remained behind saw the plain, warm and lazy, surge up once more until only the dust was to be seen, dancing from one side to another like a blond figure, inconsistent and remote, engaged in a drunken dance in which she seemed to dissolve.

THE POEM ABOUT SHADOWS

Chapter 3

MY EYES PRACTICED on the sacred morning’s shadows and I learned to tell them apart by their darkness and their light

they seemed fashioned from penumbra and time and to be perishable or perfectible depending on the sun’s brightness and the location of beings and things

leading a perilous existence where the chance encounters that caused them to shimmer destroyed them

although some lasted beyond the day, for when nightfall came another light was lit next to the object that cast them, causing them to move slightly

some were very limpid and silence encompassed them in a clarity like an expanse of water that seemed to bathe them

my eyes ran over them, whether they were standing, lying down, or bending over as if to drink drops of light from the sun-drenched grass and among them my being composed its song

shadows, I thought, confer reality on objects by serving as their negatives or ghosts and dragging themselves across the floor or sliding down the wall as insubstantial doubles; there’s something servile about them, or inscrutably humble

they are the secret world, the counterweight, and the other landscape of the radiant day

I could tell the age of some and whether they were newly born or old by their condition on the dust and others were so riddled with holes that they were pale remains or ruins of shadows

on them the day narrated its variety, displayed its temperature, and revealed the hour

and suddenly in the afternoon there were unending shadows singing on the ground at the same time

spilled next to unending beings and things in the quiet landscape singing at the foot of a mountain or beside a black dog or a white chair or a little girl

here and there pointy and round in silent music

they intertwined, they intermingled, they piled up or, terribly solitary,

were cast by the root of a lone tree on the hill