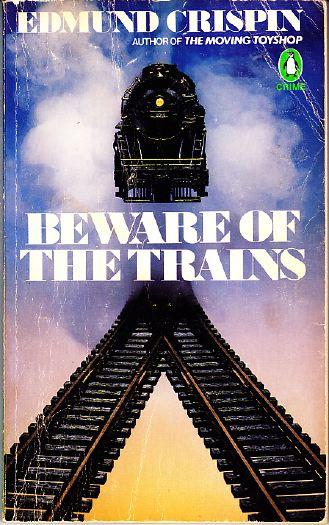

Beware of the Trains

Edmund Crispin

Beware of the Trains

A whistle blew; jolting slightly, the big posters on the hoardings took themselves off rearwards—and with sudden acceleration, like a thrust in the back, the electric train moved out of Borleston Junction, past the blurred radiance of the tall lamps in the marshalling-yard, past the diminishing constellations of the town’s domestic lighting, and so out across the eight-mile isthmus of darkness at whose further extremity lay Clough. Borleston had seen the usual substantial exodus, and the few remaining passengers—whom chance had left oddly, and, as it turned out, significantly distributed—were able at long last to stretch their legs, to transfer hats, newspapers and other impedimenta from their laps to the vacated seats beside them, and for the first time since leaving Victoria to relax and be completely comfortable. Mostly they were somnolent at the approach of midnight, but between Borleston and Clough none of them actually slept. Fate had a conjuring trick in preparation, and they were needed as witnesses to it.

The station at Clough was not large, nor prepossessing, nor, it appeared, much frequented; but in spite of this, the train, once having stopped there, evinced an unexpected reluctance to move on. The whistle’s first confident blast having failed to shift it, there ensued a moment’s offended silence; then more whistling, and when that also failed, a peremptory, unintelligible shouting. The train remained inanimate, however, without even the usual rapid ticking to enliven it. And presently Gervase Fen, Professor of English Language and Literature in the University of Oxford, lowered the window of his compartment and put his head out, curious to know what was amiss.

Rain was falling indecisively. It tattooed in weak, petulant spasms against the station roof, and the wind on which it rode had. a cutting edge. Wan bulbs shone impartially on slot-machines, timetables, a shuttered newspaper-kiosk; on governmental threat and commercial entreaty; on peeling green paint and rust-stained iron. Near the clock, a small group of men stood engrossed in peevish altercation. Fen eyed them with disapproval for a moment and then spoke.

“Broken down?” he enquired unpleasantly. They swivelled round to stare at him. “Lost the driver?” he asked.

This second query was instantly effective. They hastened up to him in a bunch, and one of them—a massive, wall-eyed man who appeared to be the Station-master—said: “For God’s sake, sir, you ‘aven’t seen ‘im, ‘ave you?”

“Seen whom?” Fen demanded mistrustfully.

“The motorman, sir. The driver.”

“No, of course I haven’t,” said Fen. “What’s happened to him?”

“‘E’s gorn, sir. ‘Ooked it, some’ow or other. ‘E’s not in ‘is cabin, nor we can’t find ‘im anywhere on the station, neither.”

“Then he has absconded,” said Fen, “with valuables of some description, or with some other motorman’s wife.”

The Station-master shook his head—less, it appeared, by way of contesting this hypothesis than as an indication of his general perplexity—and stared helplessly up and down the deserted platform. “It’s a rum go, sir,” he said, “and that’s a fact.”

“Well, there’s one good thing about it, Mr. Maycock,” said the younger of the two porters who were with him. “‘E can’t ‘ave got clear of the station, not without being seen.”

The Station-master took some time to assimilate this, and even when he had succeeded in doing so, did not seem much enlightened by it. “‘Ow d’you make that out, Wally?” he enquired.

“Well, after all, Mr. Maycock, the place is surrounded, isn’t it?”

“Surrounded, Wally?” Mr. Maycock reiterated feebly. “What d’you mean, surrounded?”

Wally gaped at him. “Lord, Mr. Maycock, didn’t you know? I thought you’d ‘a’ met the Inspector when you came back from your supper.”

“Inspector?” Mr. Maycock could scarcely have been more bewildered if his underling had announced the presence of a Snab or a Greevey. “What Inspector?”

“Scotland Yard chap,” said Wally importantly. “And ‘alf a dozen men with ‘im. They’re after a burglar they thought’d be on this train.”

Mr. Maycock, clearly dazed by this melodramatic intelligence, took refuge from his confusion behind a hastily contrived breastwork of outraged dignity. “And why,” he demanded in awful tones, “was I not hinformed of this ‘ere?”

“You ‘ave bin informed,” snapped the second porter, who was very old indeed, and who appeared to be temperamentally subject to that vehement, unfocussed rage which one associates with men who are trying to give up smoking. “You ‘ave bin informed. We’ve just informed yer.”

Mr. Maycock ignored this. “If you would be so kind,” he said in a lofty manner, “it would be ‘elpful for me to know at what time these persons of ‘oom you are speaking put in an appearance ‘ere.”

“About twenty to twelve, it’d be,” said Wally sulkily. “Ten minutes before this lot was due in.”

“And it wouldn’t ‘ave occurred to you, would it” -here Mr. Maycock bent slightly at the knees, as though the weight of his sarcasm was altogether too much for his large frame to support comfortably—”to ‘ave a dekko in my room and see if I was ‘ere? Ho no. I’m only the Station-master, that’s all I am.”

“Well, I’m very sorry, Mr. Maycock,” said Wally, in a tone of voice which effectively cancelled the apology out, “but I wasn’t to know you was back, was I? I told the Inspector you was still at your supper in the village.”

At this explanation, Mr. Maycock, choosing to overlook the decided resentment with which it had been delivered, became magnanimous. “Ah well, there’s no great ‘arm done, dare I say,” he pronounced; and the dignity of his office having by now been adequately paraded, he relapsed to the level of common humanity again. “Burglar, eh? Was ‘e on the train? Did they get ‘im?”

Wally shook his head. “Not them. False alarm, most likely. They’re still ‘angin’ about, though.” He jerked a grimy thumb towards the exit barrier. “That’s the Inspector, there.”

Hitherto, no one had been visible in the direction indicated. But now there appeared, beyond the barrier, a round, benign, clean-shaven face surmounted by a grey Homburg hat, at which Fen bawled “Humbleby!” in immediate recognition. And the person thus addressed, having delivered the injunction “Don’t move from here, Millican” to someone in the gloom of the ticket-hall behind him, came on to the platform and in another moment had joined them.

He was perhaps fifty-five: small, as policemen go, and of a compact build which the neatness of his clothes accentuated. The close-cropped greying hair, the pink affable face, the soldierly bearing, the bulge of the cigar-case in the breast pocket and the shining brown shoes—these things suggested the more malleable sort of German petit bourgeois; to see him close at hand, however, was to see the grey eyes—bland, intelligent, sceptical—which effectively belied your first, superficial impression, showing the iron under the velvet. “Well, well,” he said. “Well, well, well. Chance is a great thing.”

“What,” said Fen severely, his head still projecting from the compartment window like a gargoyle from a cathedral tower, “is all this about a burglar?”

“And you will be the Station-master.” Humbleby had turned to Mr. Maycock. “You were away when I arrived here, so I took the liberty—”

“That I wasn’t, sir,” Mr. Maycock interrupted, anxious to vindicate himself. I was in me office all the time, only these lads didn’t think to look there… ‘Ullo, Mr. Foster.” This last greeting was directed to the harassed Guard, who had clearly been searching for the missing motorman. “Any luck?”

“Not a sign of im,” said the Guard sombrely. “Nothing like this ‘as ever ‘appened on one of my trains before.”

“It is ‘Inkson, isn’t it?”

The Guard shook his head. “No. Phil Bailey.”

“Bailey?”

“Ah. Bailey sometimes took over from ‘Inkson on this run.” Here the Guard glanced uneasily at Fen and Humbleby. “It’s irregular, o’ course, but it don’t do no ‘arm as I can see. Bailey’s ‘ome’s at Bramborough, at the end o’this line, and ‘e’d ‘ave to catch this train any’ow to get to it, so ‘e took over sometimes when ‘Inkson wanted to stop in Town… And now this ‘as to ‘appen. There’ll be trouble, you mark my words.” Evidently the unfortunate Guard expected to be visited with a substantial share of it.

“Well, I can’t ‘old out no longer,” said Mr. Maycock. “I’ll ‘ave to ring ‘Eadquarters straight away.” He departed in order to do this, and Humbleby, who still had no clear idea of what was going on, required the others to enlighten him. When they had done this: “Well,” he said, “one thing’s certain, and that is that your motorman hasn’t left the station. My men are all round it, and they had orders to detain anyone who tried to get past them.”

At this stage, an elderly business man, who was sharing the same compartment with Fen and with an excessively genteel young woman of the sort occasionally found behind the counters of Post Offices, irritably enquired if Fen proposed keeping the compartment window open all night. And Fen, acting on this hint, closed the window and got out on to the platform.

“None the less,” he said to Humbleby, “it’ll be as well to interview your people and confirm that Bailey hasn’t left. I’ll go the rounds with you, and you can tell me about your burglar.”

They left the Guard and the two porters exchanging theories about Bailey’s defection, and walked along the platform towards the head of the train. “Goggett is my burglar’s name,” said Humbleby. “Alfred Goggett. He’s wanted for quite a series of jobs, but for the last few months he’s been lying low, and we haven’t been able to put our hands on him. Earlier this evening, however, he was spotted in Soho by a plain-clothes man named, incongruously enough, Diggett…”

“Really, Humbleby…

“…And Diggett chased him to Victoria. Well, you know what Victoria’s like. It’s rather a rambling terminus, and apt to be full of people. Anyway, Diggett lost his man there. Now, about mid-day today one of our more reliable narks brought us the news that Goggett had a hide-out here in Clough, so this afternoon Millican and I drove down here to look the place over. Of course the Yard rang up the police here when they heard Goggett had vanished at Victoria; and the police here got hold of me; and here we all are. There was obviously a very good chance that Goggett would catch this train. Only unluckily he didn’t.”

“No one got off here?”

“No one got off or on. And I understand that this is the last train of the day, so for the time being there’s nothing more we can do. But sooner or later, of course, he’ll turn up at his cottage here, and then we’ll have him.”

“And in the meantime,” said Fen thoughtfully, “there’s the problem of Bailey.”

“In the meantime there’s that. Now let’s see…”

It proved that the six damp but determined men whom Humbleby had culled fiom the local constabulary had been so placed about the station precincts as to make it impossible for even a mouse to have left without their observing it; and not even a mouse, they stoutly asserted, had done so. Humbleby told them to stay where they were until further orders, and returned with Fen to the down platform.

“No loophole there,” he pronounced. “And it’s an easy station to—um—invest. If it had been a great sprawling place like Borleston, now, I could have put a hundred men round it, and Goggett might still have got clear… Of course, it’s quite possible that Borleston’s where he did leave the train.”

“One thing at a time,” said Fen rather peevishly. “It’s Bailey we’re worrying about now—not Goggett.”

“Well, Bailey’s obviously still on the station. Or else somewhere on the train. I wonder what the devil he thinks he’s up to?”

“In spite of you and your men, he must have been able to leave his cabin without being observed.” They were passing the cabin as Fen spoke, and he stopped to peer at its vacant interior. “As you see, there’s no way through from it into the remainder of the train.”

Humbleby considered the disposition of his forces, and having done so: “Yes,” he admitted, “he could have left the cabin without being seen; and for that matter, got to shelter somewhere in the station buildings.”

“Weren’t the porters on the platform when the train came in?”

“No. They got so overwrought when I told them what I was here for—the younger one especially—that I made them keep out of the way. I didn’t want them gaping when Goggett got off the train and making him suspicious—he’s the sort of man who’s quite capable of using a gun when he finds himself cornered.”

“Maycock?”

“He was in his office—asleep, I suspect. As to the Guard, I could see his van from where I was standing, and he didn’t even get out of it till he was ready to start the train off again…” Humbleby sighed. “So there really wasn’t anyone to keep an eye on the motorman’s doings. However, we’re bound to find him: he can’t have left the precincts. I’ll get a search-party together, and we’ll have another look—a systematic one, this time.”

Systematic or not, it turned out to be singularly barren of results. It established one thing only, and that was, that beyond any shadow of doubt the missing motorman was not anywhere in, on or under the station, nor anywhere in, on or under his abandoned train.

And unfortunately, it was also established that he could not, in the nature of things, be anywhere else.

Fen took no part in this investigation, having already foreseen its inevitable issue. He retired, instead, to the Station-master’s office, by whose fire he was dozing when Humbleby sought him out half an hour later.

“One obvious answer,” said Humbleby when he had reported his failure, “is of course that Bailey’s masquerading as someone else—as one of the twelve people (that’s not counting police) who definitely are cooped up in this infernal little station.”

“And is he doing that?”

“No. At least, not unless the Guard and the two porters and the Station-master are in a conspiracy together—which I don’t for a second believe. They all know Bailey by sight, at least, and they’re all certain that no one here can possibly be him.”

Fen yawned. “So what’s the next step?” he asked.

Whit I ought to have done long ago: the next step is to find out if there’s any evidence Bailey was driving the train when it left Borleston… Where’s the telephone?”

“Behind you.”

“Oh, yes… I don’t understand these inter-station phones, so I’ll use the ordinary one… God help us, hasn’t that dolt Maycock made a note of the number anywhere?”

“In front of you.”

“Oh, yes… 51709.” Humbleby lifted the receiver, dialed and waited. “Hello, is that Borleston Junction?” he said presently. “I want to speak to the station-master. Police business… Yes, all right, but be quick.” And after a pause: “Station-master? This is Detective-Inspector Humbleby of the Metropolitan C.I.D.. I want to know about a train which left Borleslon for Clough and Bramborough at—at—“

“A quarter to midnight,” Fen supplied.

“At a quarter to midnight…Good heavens, yes, this last midnight that we’ve just had…Yes, I know it’s held up at Clough; so am I…No, no, what I want is information about who was driving it when it left Borleston: eyewitness information…You did?…You actually saw Bailey yourself? Was that immediately before the train left?…It was; well then, there’s no chance of Bailey’s having hopped out, and someone else taken over, after you saw him?…I see: the train was actually moving out when you saw him at the controls. Sure you’re not mistaken? This is important…Oh, there’s a porter who can corroborate it, is there?…No, I don’t want to talk to him now…All right…Yes…Good-bye.”

Humbleby rang off and turned back to Fen. “So that,” he observed, “is that.”

“So I gathered.”

“And the next thing is, could Bailey have left the train between Borleston and here?”

“The train,” said Fen, “didn’t drive itself in, you know.”

“Never mind that for the moment,” said Humbleby irritably. Could he?”

“No. He couldn’t. Not without breaking his neck. We did a steady thirty-five to forty all the way, and we didn’t stop or slow down once.”

There was a silence. “Well, I give up,” said Humbleby. “Unless this wretched man has vanished like a sort of soap bubble—”

“It’s occurred to you that he may be dead?”

“It’s occurred to me that he may be dead and cut up into little pieces. But I still can’t find any of the pieces… Good Lord, Fen, it’s like—it’s like one of those Locked-Room Mysteries you get in books: an Impossible Situation.”

Fen yawned again. “Not impossible, no,” he said. “Rather a simple device, really…” Then more soberly: “But I’m afraid that what we have to deal with is something much more serious than a mere vanishing. In fact—”

The telephone rang, and after a moment’s hesitation Humbleby answered it. The call was for him; and when, several minutes later, he put the receiver back on its hook, his face was grave.

“They’ve found a dead man,” he said, “three miles along the line towards Borleston. He’s got a knife in his back and has obviously been thrown out of a train. From their description of the face and clothes, it’s quite certainly Goggett. And equally certainly, that”—he nodded towards the platform—“is the train he fell out of… Well, my first and most important job is to interview the passengers. And anyone who was alone in a compartment will have a lot of explaining to do.”

Most of the passengers had by now disembarked, and were standing about in various stages of bewilderment, annoyance and futile enquiry. At Humbleby’s command, and along with the Guard, the porters and Mr. Maycock, they shuffled, feebly protesting, into the waiting-room. And there, with Fen as an interested onlooker, a Grand Inquisition was set in motion.

Its results were both baffling and remarkable. Apart from the motorman, there had been nine people on the train when it left Borleston and when it arrived at Clough; and each of them had two others to attest the fact that during the whole crucial period he (or she) had behaved as innocently as a new-born infant. With Fen there had been the elderly business man and the genteel girl; in another compartment there had likewise been three people, no one of them connected with either of the others by blood, acquaintance, or vocation; and even the Guard had witnesses to his harmlessness, since from Victoria onwards he had been accompanied in the van by two melancholy men in cloth caps, whose mode of travel was explained by their being in unremitting personal charge of several doped-looking whippets. None of these nine, until the first search for Bailey was set on foot, had seen or heard anything amiss. None of them (since the train was not a corridor train) had had any opportunity of moving out of sight of his or her two companions. None of them had slept. And unless some unknown, travelling in one of the many empty compartments, had disappeared in the same fashion as Bailey—a supposition which Humbleby was by no means prepared to entertain—it seemed evident that Goggett must have launched himself into eternity unaided.

It was at about this point in the proceedings that Humbleby’s self-possession began to wear thin, and his questions to become merely repetitive; and Fen, perceiving this, slipped out alone on to the platform. When he returned, ten minutes later, he was carrying a battered suitcase; and regardless of Humbleby, who seemed to be making some sort of speech, he carried this impressively to the centre table and put it down there.

“In this suitcase,” he announced pleasantly, as Humbleby’s flow of words petered out, “we shall find, I think, the motorman’s uniform belonging to the luckless Bailey.” He undid the catches. “And in addition, no doubt… Stop him, Humbleby!”

The scuffle that followed was brief and inglorious. Its protagonist, tackled round the knees by Humbleby, fell, struck his head against the fender, and lay still, the blood welling from a cut above his left eye.

“Yes, that’s the culprit,” said Fen. “And it will take a better lawyer than there is alive to save him from a rope’s end.”

Later, as Humbleby drove him to his destination through the December night, he said: “Yes, it had to be Maycock. And Goggett and Bailey had, of course, to be one and the same person. But what about motive?”

Humbleby shrugged. “Obviously, the money in that case of Goggett’s. There’s a lot of it, you know. It’s a pretty clear case of thieves falling out. We’ve known for a long time that Goggett had an accomplice, and it’s now certain that that accomplice was Maycock. Whereabouts in his office did you find the suitcase?”

“Stuffed behind some lockers—not a very good hiding-place, I’m afraid. Well, well, it can’t be said to have been a specially difficult problem. Since Bailey wasn’t on the station, and hadn’t left it, it was clear he’d never entered it. But someone had driven the train in-and who could it have been but Maycock? The two porters were accounted for—by you; so were the Guard and the passengers—by one another; and there just wasn’t anyone else.

“And then. of course, the finding of Goggett’s body clinched it. He hadn’t been thrown out of either of the occupied compartments, or the Guard’s van; he hadn’t been thrown out of any of the unoccupied compartments, for the simple reason that there was nobody to throw him. Therefore he was thrown out of the motorman’s cabin. And since, as I’ve demonstrated, Maycock was unquestionably in the motorman’s cabin, it was scarcely conceivable that Maycock had not done the throwing.

‘Plainly, Maycock rode or drove into Borleston while he was supposed to be having his supper, and boarded the train—that is, the motorman’s cabin—there. He kept hidden till the train was under way, and then took over from Goggett-Bailey while Goggett-Bailey changed into the civilian clothes he had with him. By the way, I take it that Maycock, to account for his presence, spun some fictional (as far as he knew) tale about the police being on Goggett-Bailey’s track, and that the change was Goggett-Bailey’s idea; I mean, that he had some notion of its assisting his escape at the end of the line.”

Humbleby nodded. ‘That’s it, approximately. I’ll send you a copy of Maycock’s confession as soon as I can get one made. It seems he wedged the safety handle which operates these trains, knifed Goggett-Bailey and chucked him out, and then drove the train into Clough and there simply disappeared, with the case, into his office. It must have given him a nasty turn to hear the station was surrounded.”

“It did,” said Fen. “If your people hadn’t been there, it would have looked, of course, as if Bailey had just walked off into the night. But chance was against him all along. Your siege, and the grouping of the passengers, and the cloth-capped men in the van—they were all part of an accidental conspiracy—if you can talk of such a thing—to defeat him; all part of a sort of fortuitous conjuring trick.” He yawned prodigiously, and gazed out of the car window. ‘Do you know, I believe it’s the dawn… Next time I want to arrive anywhere, I shall travel by bus.”

Humbleby Agonistes

“In my job,” said Detective-Inspector Humbleby, “a man expects to be shot at every now and again. It’s an occupational risk, like pneumoconiosis in coal-mining, and when you’re on duty you’ve obviously got to be prepared for it to crop up. But a social call on an old acquaintance is quite a different matter. Here am I on my Sabbatical. I drop in to see this man I’ve known ever since the 1914 war. And what happens? Before I have a chance to as much as open my mouth and ask him how he is, he snatches a damned great revolver out of his pocket and lets it off at me. Well, I was petrified. Anyone would be. I was so astonished I literally couldn’t move.”

“He doesn’t seem to have hit you, though.” From the depths of the armchair in his rooms at St. Christopher’s, Gervase Fen, University Professor of English Language and Literature, regarded his guest with a clinical air. “l see no wound,” he elaborated.

“There is no wound. Three times he fired,” said Humbleby dramatically, “and three times he missed. Which, of course, makes it all the odder.”

“Why ‘of course’? I’ve always understood that revolvers—”

“I say ‘of course’ because Garstin-Walsh, whom I’m speaking of, is a retired Army man: a brevet-rank Colonel, to be precise … Yes, I know what you’re going to tell me. You’re going to tell me that Army men seldom actually use revolvers, even though they may carry them; and that consequently it’s naïve to expect them to be good marksmen. Agreed. But the trouble in this instance is that Garstin-Walsh has always made a hobby of shooting in general—he’s the sort of man it’s impossible to visualise outside the context of dogs and guns and an interest in dahlias—and of pistol-shooting in particular. That`s why I’m so certain he missed me on purpose: at a yard’s range even I could hardly go wrong… But perhaps I’d better begin at the beginning.”

Fen nodded gravely. “Perhaps you had.”

“As you know,” said Humbleby, “I was in Military Intelligence during the 1914 war; and it was while I was investigating an unimaginative piece of sabotage at an arms depot near Loos that I first met Garstin·Walsh, who at that time was a Captain in the Supply Corps. It’d be an exaggeration to say that we became close friends—and looking back on it, I can’t quite see why we should have become friends at all, because our temperaments weren’t at all alike, and we had very few interests in common. Still, for some obscure reason we did in fact get on well together; and I think that much of his attraction for me must have been due to his complete humourlessness—we were all a bit hysterical in those days, whether we knew it or not, and a man who never laughed was unexpectedly restful.”

“We used to meet, then, as often as we could; and after the Armistice we kept up a sporadic correspondence and managed some sort of reunion once or twice every year. Then eighteen months ago Garstin-Walsh retired and went to live at a village called Uscombe, which is a few miles from Exeter; and since I was staying with my sister at Exmouth, and hadn’t seen him for some considerable time, I decided, the day before yesterday, to drive over and pay him a surprise visit.

“I left Exmouth immediately after breakfast and got to Uscombe about ten-thirty. Uscombe’s not as cut off from the rest of the world as some Devon villages, because it’s only a quarter of a mile from the main London road; but in all other respects it’s fairly typical—settled to some extent by middle-class ‘foreigners,’ I mean, with an unsuccessful preparatory boarding-school in a tumble-down manor-house, and a church tower scheduled dangerous; you know the sort of place. I hadn’t been there before, so I stopped at one of the village shops to enquire for Garstin-Walsh’s house. And the way they looked at me, as they gave me directions, was the first intimation I had that anything was wrong.

“The house proved to be a nice, trim, up-to-date little red-brick villa beyond the church, with lots of chrysanthemums in the garden and a carefully weeded front lawn; so that was all right. But then the trouble started. The painters were in, for one thing; an Exeter C.I.D. Inspector was hanging about the hall, for another; and an undeniably dead body was in process of being removed by a mortuary van. I need hardly tell you that if I’d known about all this I should have gone back to Exmouth and tried again some other day; but by the time the situation became clear I’d rung, and been let in by the housekeeper, and so couldn’t very well escape without positive incivility.

“Garstin-Walsh was still upstairs dressing. But the Exeter man, Jourdain he was called, had heard me give my name to the housekeeper, and lost no time in introducing himself. ‘You’ll be curious,’ he said dogmatically, ‘about that body they’ve just taken away.’ I denied this, but it was no good, he insisted on telling me about the affair just the same. And stripped of inessentials, the story I heard, while we waited in the hall for Garstin-Walsh to come down, was as follows:

“A year previously, the ramshackle cottage near Garstin-Walsh’s house had been rented by one Saul Brebner, he whose remains were at present en route for the Exeter City Mortuary. A powerful, malignant, drunken, slovenly man of about fifty was Brebner, and the people of Uscombe had gone in fear of him almost from the day of his arrival. He was without family, lived alone in squalor, had money in spite of working not at all, and divided his time fairly evenly between poaching and The Three Crowns. The police kept an eye on him, of course, but he succeeded in steering clear of them. And the only person in the village who ever had a good word to say for him was, surprisingly enough, Garstin-Walsh.

“That there was a reason for this the village soon discovered: Brebner had been Garstin-Walsh’s batman in the 1914 war, and it was realised that Garstin-Walsh’s toleration of the creature derived from this. However, the toleration wasn’t by any means mutual: Brebner made no secret of his loathing for Garstin-Walsh, and from time to time, when in liquor, was heard to hint that there were phases of the Colonel’s career which would not bear investigation. The village, which quite liked Garstin-Walsh, discounted these innuendos as the vapourings of malice, and even when Brebner became more specific, referring to misappropriation of supplies in France, refused to take him seriously. Indeed, on the night of the incident which wrote finis to Brebner’s unlovely existence, he was so vituperative about Garstin-Walsh in the public bar of The Three Crowns that there was very nearly a riot, and when he left the pub at closing time—half past ten—he was dangerously enraged as well as, what was normal, dangerously drunk.

“Garstin-Walsh reached home that evening at about a quarter to eleven (I’m referring, you understand, to what to me, visiting him, was the previous evening). He’d spent the day acting as starter at the village sports, had dined at the Vicarage, and afterwards had worked with the Vicar at the parish accounts; and he got back to his house just in time to meet his solicitor on the doorstep, the said solicitor having driven there, on urgent business, from Exeter. Well, they went into the study, a large room on the ground floor, and got on with whatever it was they had to discuss. And according to the solicitor, a respectable old party named Weems, it was exactly five to eleven when the french windows burst open and Brebner, carrying a double-barrelled shotgun, lurched into the room.

“It was all over in a moment. Brebner levelled the gun at Garstin-Walsh and fired off one barrel. But he was pretty far gone, and the pellets spattered the room without touching their target. The second barrel remained. Steadying himself, Brebner aimed again. And Garstin-Walsh, grabbing up the pistol which he’d been using all day to start races, and which he’d reloaded immediately on his return, fired just in time to save his own life. It was good shooting, partly because the end of the room where Brebner stood was in semi-darkness, and partly because Garstin-Walsh, according to Weems’ deposition, was fairly thoroughly unnerved. Brebner staggered, dropped the shotgun, and collapsed on the carpet with a bullet in his head.

“Well, the village constable was summoned; and since Brebner, though unconscious, was still just alive, a doctor was summoned too. The doctor refused to have Brebner moved, and Garstin-Walsh was forced to allow him to stay in the study with a nurse to look after him, until next morning at nine o’clock he died there without recovering consciousness.”

Humbleby sucked complacently at his cheroot. “That, then, was the story Jourdain told me while we waited for Garstin-Walsh to appear. A clear case of self-defence, and a very good riddance, and the only reason Jourdain was there was to have a look at the study where the thing had happened, for the purpose of making the usual routine report.

“He’d just finished his tale when Garstin-Walsh came downstairs. Garstin-Walsh has always been a stringy, bony sort of man, and even when I first knew him he looked old; so the years have really altered him very little, in comparison with the rest of us. At the moment he was a bit haggard and white, and I guessed he hadn’t slept much; I got the impression, too, that all the time he was talking to us he was preoccupied, inwardly, with some sort of intellectual balancing trick: I mean that he had the precarious, constricted air you notice in people who are trying to think of two things at once. But he was very civil with us, brushing aside my suggestion that should go away and come back at some more convenient time; and he took Jourdain and myself into the study as soon as the nurse, who’d been packing and tidying, quitted it.

“It was a pleasant room, its pleasantness a bit marred, at the moment, by surgical smells and paint smells (the painters hadn’t finished with it till supper-time the previous day); and while Jourdain explained that he’d come to look at the shot-holes and so forth—rather needlessly, since he’d already said all that to the housekeeper, and she, presumably, had conveyed it to Garstin-Walsh—I had a look round. There was more shabbiness than I should have expected: Garstin-Walsh had—has—an unusually spick-and-span sort of mind, so that the threadbare carpet and the dented brass coal-scuttle, which you wouldn’t notice these days in most people’s houses, surprised me at first. But of course, there was, in view of Brebner’s insinuations and independent income, one very plausible explanation of the shabbiness. And it’ll show you how superficial my friendship with Garstin-Walsh was when I say that the possibility of blackmail neither shocked nor astonished me particularly, and that I wasn’t conscious of there being any disloyalty involved in my having my suspicions about Garstin-Walsh’s professional past.

“So there we all were: Garstin-Walsh fidgeting in a monkish kind of dressing-gown which he wore over his shirt and plus-fours instead of a coat, Jourdain gabbling away as only a County D.I. can gabble, and myself thinking disinterested thoughts about consignments of service dress which had gone astray, and never been recovered, during the first months of 1917. It’s no use my pretending I was comfortable. I wasn’t. On the other hand, my uneasiness had nothing whatever to do with blackmail or its pretexts, or with the problem of what, in this particular instance, I ought to do about them—since I intended, very firmly indeed, to do nothing about them whatever. No, it was more the sort of sensation you have when in crossing a road you hear a car coming at you and can’t for the moment either see it or judge, from the sound of it, what direction it’s coming from. I remember I was actually humming quietly, to keep my spirits up, as I strolled over to the french windows to have a look at the view.

“And that was when it happened.

“The village constable hadn’t confiscated Garstin-Walsh’s revolver—there was no reason, after all, why he should—and apparently Garstin-Walsh had taken it to bed with him. Anyway, he had it on him now, in a pocket of his dressing-gown, and I was just on the point of making some remark about the garden when he suddenly whipped the thing out, shouting incoherently, and fired it at me. I was simply flabbergasted, of course. I stood there helplessly trying to remember the details of Gross’s suicidal method of disarming people with guns, and Jourdain stood there goggling, and one shot smashed a vase on a table beside me, and another smashed a pane of the french windows, and a third went heaven knows where, and then, when I thought my last hour had certainly come, Garstin-Walsh waved me away—still shouting, still incoherent—and backed out of the french windows and fled. Almost immediately Jourdain went after him—and to cut a long story short, caught up with him at the bottom of the garden, where he’d stopped and was standing like a man in a trance, staring at the revolver in his hand as if he couldn’t imagine what it was or how he’d come by it. He surrendered it, and returned to the with Jourdain, like a lamb; and he was more dazed and bewildered than I’ve ever seen anyone in my life. He knew what he’d done, all right, but he couldn’t account for his motives in doing it. ‘It—it was like last night,’ he stammered.

‘When I saw you standing by those windows I remembered Brebner, and the gun was in my pocket and-‘

“Well, it wasn’t attempted murder, because plainly there was no malice; and there’s no such thing as attempted manslaughter. So we telephoned his doctor and got him to bed, still quite bemused—and in bed, for all I know, he is still. The doctor, of course, understood all about it: it was delayed shock, or post-traumatic automatism or some such thing, and the only surprising feature of the business was that I was still alive. I can tell you, I felt quite ashamed of myself for upsetting what otherwise would have been a perfect sample-phenomenon for the medical text-books… Well, I went away, and today, as you know, travelled up here to Oxford, and—”

“Why?” Fen interrupted. ‘Why did you come to Oxford? To see me?”

“Well, yes.”

“You’re not satisfied, then?”

‘I’m not,” said Humbleby. “Everything about the affair fits, and seems quite innocent, excepting just one obstinate little fragment.”

“And that is?”

‘He unloaded the gun, you see. After he’d shot at me, and before Jourdain grabbed him, he unloaded the gun and threw the spent cartridge-cases away somewhere. When he handed the gun to Jourdain its chambers were empty. And why the devil, I ask myself, stroud he have done that?”

Outside the windows of the first-floor room in which they sat, a clock struck six. Dusk was falling; the gleam had gone from the gilt titles of the books ranged along the walls, and from the college dining-hall you could hear the clink and rattle of plates being laid for dinner. In the broad, high room, with its painted panels, its luxurious chairs, its huge flat-topped desk and its weird medley of pictures, Detective-Inspector Humbleby gestured expressively and fell silent—and for the time being Fen seemed disposed to let the silence stay. His ruddy, clean-shaven face was pensive; his long, lean body sprawled gracelessly, heels on the fender; his brown hair, ineffectually plastered down with water, stood up, as usual, in mutinous spikes at the crown of his head. For perhaps two minutes he remained staring, mute and motionless, into the amber depths of his glass…

And then, suddenly, he chuckled.

“Rather nice, yes,” he said. “Tell me, were the spent cart ridges ever found?”

“No. At the time, of course, we didn’t bother about them. But Jourdain was hunting for them yesterday, and he couldn’t find them anywhere.”

Fen’s amusement grew. “Nor will he ever, I imagine—unless your Colonel Garstin-Walsh is a hopeless blunderer.”

“But how are they important? I don’t see—”

“Don’t you?” Fen lit a cigarette and reached for an ashtray. “I should imagine, myself, that they’re important for the reason that one of them is a blank.”

“A blank?” Humbleby’s face was very much that.

And Fen roused himself, speaking more energetically. ‘You’ll agree that Garstin-Walsh obviously possessed blanks; no man in his senses starts races at the village sports with live ammunition.”

“Yes, I agree about that.”

“And two of the shots he fired at you smashed things, so they were real enough. But what happened to the third?”

Humbleby was anything but stupid; after a moment’s reflection he nodded abruptly. “If that third shot was a blank,” he said, “then that would mean… No, wait. I see what you’re getting at, but I can’t quite work it out for the moment. So go on.”

“We’re assuming, remember, that Garstin-Walsh got rid of those cartridge-cases advisedly—that he wasn’t in fact, the maniac he seemed. Now, it’s possible to conceive quite a number of solid reasons for his acting as he did; but so far as my deductions have gone, there’s only one of them that covers all the facts. A blank cartridge is recognisably different from a live one. Let’s take it, then, that the spent shells were thrown away in order to conceal the presence of a blank among them, in case either you or Jourdain should be curious enough to investigate the gun. What follows? Quite simply, the fact that Garstin-Walsh fired two live shots and a blank at you. And if he did that, it can only have been because Jourdain was just about to examine the study, and there was a bullet-hole in the wall which had to be accounted for somehow.

“Now, there was no bullet-hole in the wall prior to the Brebner shooting; if there had been, the painters would have found it and repaired it. So what would have happened if Garstin-Walsh hadn’t staged his shooting act with you? Jourdain, finding a bullet-hole in the wall, would have reasoned thus:

“‘This hole must be the result of the single shot Garstin—Walsh fired at Brebner last night.

“‘It can’t have been made subsequently, because Brebner and the nurse were in here all night.

“‘Therefore when Garstin-Walsh fired at Brebner he missed.

“‘But there is a bullet from Garstin-Walsh’s revolver lodged in Brebner’s skull.

“‘Therefore Garston-Walsh must have shot Brebner earlier on, before he returned here and met Weems.

“‘And that doesn’t look much like self-defence; it looks like murder.’

“That Brebner was blackmailing Garstin-Walsh is obvious enough. It’s obvious, too, that Garstin-Walsh decided he must put a stop to it. So as I see it, he must have shot Brebner after Brebner left The Three Crowns, have gone to the cottage to remove whatever evidence of misappropriation of Army supplies Brebner was using, and have then returned to his house. He’d shot Brebner in the skull, and so naturally assumed that he was dead, but—”

“Yes, that’s the difficulty,” Humbleby interposed. “The idea of a man with a bullet in his brain rushing about with a shotgun intent on vengeance—”

“Oh come, Humbleby.” Fen was mildly shocked. “It’s not common, I grant you, but there are plenty of cases on record, John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated Lincoln, is one. Gross and Taylor and Sydney Smith quote others. Brain injuries don’t kill at once, and in a certain proportion of cases they don’t kill at all. They don’t necessarily involve loss of consciousness or inability to act, either: there was that fourteen-year-old boy, you remember, who tripped and fell on an iron rod he was carrying; the rod went clean through his brain; but all that happened was that he pulled it out and went on home, and he didn’t die until more than a week later, after an interlude during which he hadn’t even felt particularly ill…

“But Garstin-Walsh must have had a nasty turn when the man he’d left for dead burst in at his french windows. No wonder he was ‘fairly thoroughly unnerved.’ No wonder his shot went wild. But no wonder, also, that Brebner could hardly hold the shotgun with which he intended to revenge himself; no wonder he collapsed just after Garstin-Walsh fired at him…

“Garstin-Walsh must have rejoiced. He’d murdered a man, and now, by the queerest combination of accidents, the thing had been made to seem a perfect case of self-defence. The only snag lay in that superfluous, that tell-tale bullet-hole in the study wall. In the excitement following Brebner’s collapse it wouldn’t be noticed—the more so if a piece of furniture were unobtrusively shifted so as to conceal it. But there was no chance during the night of removing the bullet and plugging the hole; and there was very little chance that Jourdain would miss it when he examined the study next morning. So Garstin-Walsh, having heard from his housekeeper of Jourdain’s presence,and intentions, and seeing no opportunity, with such a crowd of people in the house, of slipping into the study and dealing with the hole before meeting Jourdain, loaded his revolver with two live cartridges and a blank; and then—you having placed yourself conveniently in position near the french windows and the bullet-hole—staged his nervous breakdown.”

There was a long silence. Then Humbleby said: “Yes, I’m sure you’re right. But it’s all conjecture, of course.”

“Oh, quite,” said Fen cheerfully. “If my theory’s false, there won’t be any proof of it. And if it’s true, there won’t be any proof of it, either. So you can take your choice. The only possibility of checking it would be if the—”

He was interrupted by the shrilling of the telephone. “That might be for me,” Humbleby told him. “I took the liberty of asking Jourdain to get in touch with me here if there was any news, so…”

And in fact the call was for him. He listened long and spoke little. And presently, ringing off, he said:

“Yes, it was Jourdain, He’s found those cartridge-cases.”

“In a place where he’d looked previously?”

“No. And none of them is a blank. Which means—”

“Which means,” said Fen as he picked up the whisky decanter and refilled their glasses, “that on this side of eternity there’s at least one thing we shall never know.”

The Drowning of Edgar Foley

In a room in Belchester Mortuary—a plain room with a faint smell of formalin, where dust-motes hung suspended in a single shaft of sunlight-the financier and the labourer lay on deal tables under greyish cotton sheets, side by side. The scene was of a sort to evoke facile moralising, all the more so since the labourer had left his wife moderately well off, whereas the financier had died penniless. But neither Gervase Fen—for whom, thanks to the repetitious insistence of the English poets, such moralising had long since lost its first freshness—nor Superintendent Best—who like most plain men felt that the democracy of death was too large and obvious and absolute a fact to require comment—was moved to remark, or even to reflect on, the commonplace irony of it, In any case, they were not, as yet, fully informed: at this stage the financier was not yet known to be a financier, was not yet docketed and filed as the undischarged bankrupt who had changed his identity, fled from London, and at last, in God knows what access of fear or despair, cut his own throat with the ragged blade of a pocket-knife in a lonely part of the moors. To the authorities he was still no better than an anonymous suicide; so that when Fen, after a brief scrutiny of the shrunken, waxy face, was able to announce that this was in fact the stranger with whom he had recently talked in the hotel bar at Belmouth, and whose touched-up photograph, issued by the police, he had seen in that morning’s papers, Superintendent Best heaved a sigh of relief.

“That’s something, sir, anyway,” he said. “It gives us a starting-point, at least—and there’s things in that conversation you had with him that’ll narrow it down quite a lot. So if you wouldn’t mind coming back to the station straight away, and making a formal statement…”

Fen nodded assent. “No other reaction so far? To the photograph, I mean?”

“Not yet. There’s almost always a bit of a time-lag, you know.”

“Ah,” said Fen affirmatively; and his eyes strayed to the shrouded occupant of the further table. “Who’s that?” he demanded.

“Chap called Edgar Foley. Drowning case. They picked him out of the water yesterday, and his widow’s coming along this morning to have a look at him.” Best consulted his watch. “And talking of that, I think it’d be a good thing if we were to clear out before they—”

But he was too late; and he was destined to reflect, later, that it was just as well he had been too late-for if Fen had never set eyes on the widow of Edgar Foley, the topic of Foley’s death might well have lapsed, and in that case an unusually mean and contemptible crime would probably have gone unpunished. For the moment, however, Best was merely embarrassed, since the room possessed only one door, and with the arrival of the newcomers his retreat was cut off. He moved back against the wall, therefore, waiting; and with Fen at his side was witness to what followed.

A Sergeant, helmet under oxter, led the way; he stood aside, holding the door, until his two companions had entered. Inevitably. it was the smaller of the two, the man, who claimed attention first, for this was an imbecile in the technical sense, of the word, an ament-flat-topped skull, decaying teeth, abnormal ears, tiny eyes, coarse skin; well below average height, but with long ape-like arms, muscularly well-developed. The age—as so often with these tragic parodies of humanity—it was impossible to guess at; but you could see the terror mastering that feeble, inarticulate brain, and you could hear the whimpering as the deformed head moved from side to side… Suddenly, with a sort of howl, the idiot turned and bolted from the room at a shambling run. And the woman who was with him said hesitantly to the Sergeant: “Shall I…?”

“He’ll be all right, ma’am, will he?”

“‘Im’ll wait outside,” she said. ‘Won’t get run over nor nothing.”

Well, my orders were, he wasn’t to be forced to do it if he didn’t want. So long as he’s safe…”

“Yes, he’s safe,” she said. ‘He won’t go away from where I am.”

And without so much as a glance at Fen or Best she moved forward to where the body of her husband lay. She was perhaps thirty-five, Fen saw: an uneducated country-woman with an impassive, slow-moving dignity of her own. Straight black hair was drawn back to a coil at the nape of her neck; her skin was very thick and smooth, ivory-complexioned; she wore no make-up of any kind. Her black coat and skirt were cheap and shabby, and her legs were bare; and because she was not dressed to attract, you overlooked, at first, the matronly shapeliness of her. She was calm, now, to the point almost of dullness; when the Sergeant drew back the sheet from the face of the man she had married her expression never altered.

“That’s ‘im,” she said emotionlessly. “That’s Foley.”

It was dispassionate and quite final. Replacing the sheet, the Sergeant ushered her out. And Fen, who had been unconsciously holding his breath, expelled it in a sigh.

“Rather a remarkable woman,” he commented. “How did her husband come to be drowned? Accident?”

Best shook his head. “It was the idiot. The idiot pushed him in—according to her, that is: there wasn’t any other witness, and the idiot can’t talk at all, can’t even understand what you’re asking him, most of the time…” Best crossed to the body of Foley, and uncovered the dead face; Fen joined him. “Not pretty, is he? Wasn’t any too pretty when he was alive, either.”

“M’m,” said Fen. “It looks as if he must have been in the water a week or more.”

For a moment Best was surprised; then abruptly he smiled.

“I was forgetting,” he said, “that you knew about these things… Six days, actually.”

“And badly knocked about, too.” Fen had pulled the sheet further down and was contemplating the body with some interest. “Rocks, I suppose: currents.”

“Rocks,” said Best. “And currents and rapids and weirs and deep pools.”

“Rapids? Weirs?” Fen looked up. “The river, you mean? I was imagining he’d been drowned in the sea.”

“No, no, sir. What happened—d’you know Yeopool?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Well, you probably wouldn’t: it’s only a tiny village, just down off the edge of the moors. Anyway, Yeopool’s where Foley and his wife lived, and that’s where he got pushed in. It’s a treacherous bit of the river there, even for anyone who can swim—and he couldn’t: so I don’t imagine he lasted long. …Afterwards, he must have got tangled up under water somehow or other. It was fifteen miles downstream, at a village called Clapton, that they picked him up yesterday, and by that time he’d been so battered that he didn’t have a shred of clothing left on him anywhere… That’s not uncommon, sir, as you’ll know.”

“In a fast-moving river,” Fen agreed, “you could almost say it was the rule. Except of course for the—”

But at this point a Mortuary attendant looked in; and: “O.K., Frank,” called Best. “All finished. Has that other lot gone?” Frank indicated that it had. “Then we’ll go, too.” Best pulled the sheet back into position. “Don’t you waste your pity on Foley, though,” he said to Fen as they left the room. “If you should feel like being sorry for him, just keep in mind what he was doing at the time the idiot shoved him in.”

“Which was?”

“He’d hit his wife and knocked her on to the ground,” said Best calmly, “and he was kicking her with his heavy boots. Not for the first time, either… Yes. He’s where he belongs. And if his widow isn’t exactly inconsolable, you can hardly blame her, can you?”

In the police-car, on the way back to the police-station, Fen remained mute; it was only when they were actually pulling into the yard that he spoke again.

“This Foley business,” he said: “are you handling it yourself?”

“No. The Chief’s handling it.”

“The Chief Constable, you mean?”

‘That’s it: Commander Bowen.”

“But does he often do that sort of thing?”

Best parked the car tidily, switched off the engine, and leaned back. “No, thank God,” he said with candour. “Point is, though, he himself lives at Yeopool. So when Mrs. Foley reported the accident—or the murder, call it what you like—to the village constable, the village constable went straight to the C.C.; and he, seeing it had to do with some of his own people—he rather fancies himself playing the Squire with ‘em—he decided he’d deal with it personally. A good thing, too,” Best added, “that it isn’t anything more complicated than what it is. A year and a half in the Thames police, thirty years ago, isn’t much training for serious C.I.D. work these days.”

“That the only qualification he has, then?”

“The only practical qualification, yes. And he’s probably forgotten most of that during the time he was in the Navy. He’s all right, of course: too strict and rigid and pound-of-flesh and letter-of-the-law for my liking, but I suppose that’s a fault on the right side; and I’ll grant you he’s read up all the text-books since he got his job with us—for what that’s worth… But they don’t appoint his sort these days.” Best reached for the door-handle. “They appoint proper full-time cops, and a darned good thing too.”

With this view Fen was on the whole in agreement. But for the time being he only nodded abstractedly, and his abstraction appeared to be deepened, rather than otherwise, by the subsequent business of dictating a statement about his recent chance encounter with the suicidal financier; so that Best was not altogether surprised when presently, while they waited for the statement to be typed, he returned to the attack.

“Motive,” he said without preamble. “Obviously Foley’s brutality to his wife was enough in itself to make her wish him dead, but was there anything more?”

“There was life-insurance.” Best shifted rather uneasily in his chair. “Not a fortune—not by any means—but a surprising lot for just a farm labourer… Look here, sir, I quite see what you’re getting at: it’s obvious the wife could have done it, and put the blame on the idiot, and no one a bit the wiser. But there’s no proof—can’t be—and what with one thing and another—”

“You think it’s best to let sleeping dogs lie.” Fen lit a cigarette. “Only sooner or later, you know, they wake up of their own accord and then there’s liable to be trouble anyway…” Did they come on here from the Mortuary—the wife, I mean, and the idiot?”

“Yes. They’re waiting here now for the C.C. to arrive.” Best craned his neck to look out of the office window. “Which he hasn’t done yet, because his car’s not in the yard. He had an informal talk with them last night, after he’d been to Clapton to look at the body, and today he’s going to have it all taken down in shorthand… Hello, here he comes. We’ll have to clear out of here now, I’m afraid-though why the devil he has to choose my office to hold his interviews in…”

“I want to stay,” Fen interrupted. “I want to be present at this thing.”

Best shrugged. “Well, you can ask, can’t you?” he said. “He’ll have heard of you all right. But I shan’t sponsor you, if you don’t mind. Life’s too short, and so’s his temper, every now and again.”

“I won’t involve you in it,” Fen promised. “What I’d better do, I think, is try to catch him as he comes in… Oh, just one other thing.”

“Yes?”

“What about the imbecile? Why was he there, that’s to say?”

“Oh, that… Well, the thing about it is, you see, that he dotes on Mrs. Foley—doggishly, I mean, nothing unpleasant—he’s always hung around her a good deal. He’s the old-style Village idiot, really—quite harmless, born in Yeopool, lived there all his life; but ever since he was a kid, Mrs. Foley’s been the only person he’s seemed to like or trust, so it’s quite logical he should have attacked Foley, and pushed him into the river, when he saw Foley mauling her.”

“Quite,” Fen murmured. “Did she go to a doctor, afterwards, by any chance—or wasn’t she hurt badly enough for that?”

Best raised his eyebrows. “Still sceptical, sir? Yes, she did see a doctor, that same evening, and he’ll tell you she was horribly bruised, with actual marks of the boot-nails on her flesh in some places. Nothing phoney about that, in fact—quite enough. actually, if she had killed him, to justify a plea of self-defence.”

“Manslaughter, more likely, I should have thought,” said Fen. “And even a quite nominal sentence for manslaughter would prevent her from touching the insurance money.”

Best’s expression hardened. “You’ve got it in for her, sir, haven’t you? You want her found guilty.”

But Fen shook his head.

“Far from it,” he answered. “There’s one person I should like to expose, if a certain guess of mine is right; but it’s not the unfortunate Mrs. Foley.” He rose. “And now I must go and look for your Chief.”

Commander Bowen was a small, slim, cheerful man with a springy step. a brown face, and neat curly grey hair. As Best had predicted, he had heard of Fen, and seemed pleased enough to meet him. And although his assent to Fen’s presence at the interview with Mrs. Foley was unenthusiastic, he did in fact give it. Accordingly, they were soon settled in Best’s office, which Best himself had in the meantime grudgingly vacated; a shorthand writer was summoned to stand by; and presently Mrs. Foley and the imbecile, together with the Yeopool village constable, were ushered in and made as comfortable as the furniture, and their own several anxieties, permitted.

The woman was much as she had been when Fen had seen her earlier; though it seemed to him that on the present occasion her face was rather more flushed, and her breathing rather more rapid. She sat bolt upright in her chair. twisting a cotton handkerchief between her hands, with the idiot close beside her. And whereas she appeared more nervous now than she had been at the Mortuary, the half-wit, in contrast, was clearly more at ease. It was impossible, Fen found, to tell how much he understood of what was going on: little enough, probably. Only when the woman addressed him directly did he show any sort of intelligence, and then he would grow restless and excitable and uncertain, like a dog given an order which it does not understand. Bowen made no attempt to question him. He addressed himself solely to the woman, with an occasional aside to the village constable; and his manner, though brisk, was sympathetic and straightforward. For the record, even details which all of them knew were elicited. And so it was that for the first time Fen heard the story in a connected, coherent form.

Mary Foley was thirty-seven years old, she said; she had been married to Edgar Foley for nearly sixteen years, but they had had no children. They lived at Rose Cottage, a farm-labourer’s cottage on the bank of the river just outside Yeopool, and Foley had worked for Mr. Thomas of Manor Farm, on whose land the cottage stood. Foley (she always spoke of him thus formally, never using his Christian name) had not been a good husband to her; he had beaten her on a number of occasions.

“Nor I couldn’t stop ‘un, neither,” the village constable interposed indignantly at this point. “Us all knew ‘twas goin’ on—as you knew it yourself, sir—but ‘er wouldn’t never say nothin’ against ‘im, so what was us to do?”

“I'd taken ‘im for better or for worse, ‘adn’t I?” she said lifelessly. “‘Twasn’t no one else’s business ‘ow ‘e treated me.”

For a moment Bowen seemed to consider debating this; but he thought better of it, and resumed his questions. Last Monday, then-

Last Monday, she said, she had left the cottage at about six o’clock with a view to strolling along the river bank and meeting Foley on his way home. Orry (this was the idiot) had been at the cottage during the afternoon, and she had given him tea and a piece of cake. But she had supposed that by the time she set out Orry was back in the village, for he knew that Foley disliked him and was normally careful to keep his distance whenever the husband was at home. Mrs Foley had not walked far; about a hundred yards from the cottage she had halted and waited, and after some ten minutes Foley had joined her. He had been in an ill humour and had picked a quarrel with her, accusing her of idleness; and when she had attempted to defend herself he had knocked her down and kicked her. She was still not very clear about what had happened next; she had a dim recollection, she said, of Orry’s shambling forward from the bushes and pushing her husband in the back, and that was all. In any case, the upshot of it was that by the time she had recovered her wits it was impossible to save him, even if she had been a swimmer, which she was not.

The idiot, who had watched her eagerly during the latter part of her story, at this point nodded vigorously, half rose from his chair, and made violent thrusting movements with his long arms. It was confirmation, of a sort. Bowen cleared his throat uncertainly.

“So that’s about the lot,” he said; and to Fen: “The river was dragged, of course, but the body must have got caught on an—ah—underwater snag of some kind, and it didn’t reappear till yesterday… Well, Mrs. Foley, I don’t think there’s anything more for you to worry about now. You’ll have to give evidence at the inquest, of course, but that won’t be at all a long business. As to Orry, we’ll have to see what we can do about getting him into a—a Home.” He turned back to Fen again, indulgently. “Is there anything you’d care to ask, Professor?”

“Just one thing,” said Fen affably, “if you don’t mind. It’s this: after the recovery of Foley’s body, what did you do with his boots?”

Bowen stiffened; and Fen, searching the man’s eyes, saw in them the justification of what he had already guessed.

“His boots, sir?” said Bowen coldly. “Are you joking?”

“No,” said Fen, unperturbed, “I’m not joking. What became of them?”

For a split second Bowen was obviously in the throes of some rapid tactical calculation; then: “The body was recovered stark naked, sir,” he answered, all at once agreeable again: “As the Clapton constable, who—ah—landed it, will tell you. A week’s immersion—rocks—the rapidity of the current—”

“Just so.” Fen smiled, but it was not a pleasant smile. “So now, Commander, there’s only one further question I need trouble you with. And it’s quite a small point, really…”

He leaned forward in his chair.

“What are you blackmailing Mrs. Foley for?” he enquired. “Money, or love?”

There are some episodes in Superintendent Best’s professional career which he has no joy in recalling; and among these, the afternoon of that particular Monday takes pride of place. It is nothing if not disconcerting to be summoned from a tranquil cup of tea to hear a woman vehemently accuse your Chief of the nastiest variety of blackmail; and if such an accusation is patently the truth, and your own duty in the matter very far from plain, then your discomfort is liable to become extreme. What happened, in the event, was that both Bowen and his subordinates were stricken by a sort of mutual paralysis. The Chief Constable’s blustering denials carried not an instant’s conviction, as he himself plainly saw. But on the other hand, his men would scarcely have felt competent to take action against him even if the blackmail charge had rested on something more substantial than Mrs. Foley’s unsupported word. Bowen had left, in the end, to go and see his solicitor, and to make—as he said—a telephone call to the Home Office; but that particular telephone call never went through. He had cooled down, and towards Best had become almost ingratiating, by the time he took himself off. But of his guilt there could be no shadow of doubt.

“All I could think of to do,” said Best to Fen that same evening, in his office, “was to ring up the Home Office myself. And they’re sending a deputation of bigwigs down here tomorrow to look into it all, so my responsibility’s finished, thank God… But, Lord, sir, you were taking a bit of risk, weren’t you? If Mrs. Foley had been too frightened to back you up, you’d have been in real trouble, and no mistake.”

Fen nodded. ‘I think it’s probably one of the chanciest things I’ve ever done,” he said. “But it wasn’t so much the question of whether Mrs. Foley would back me up that was worrying me. She’s obviously a morally decent sort of woman; I didn’t think it was likely to be money Bowen was blackmailing her for; and so I was fairly sure that if she were given a chance of making a clean breast of the thing, she’d probably do it.

“No, the real danger was that Bowen simply hadn’t noticed the evidence which proved Mrs. Foley guilty; or alternatively, that if he had noticed it, he was keeping quiet about it out of humanitarian feeling or local patriotism or something (there was the chance, too, that he’d been having an affair with Mrs. Foley, and was protecting her for that reason). To the first of these possibilities the objections were (a) that Bowen had been in the Thames police, (b) that he’d been in the Navy, and (c) that he’d recently read the standard text-books on Criminal Investigation. To the second, the objection was that—to use your words—Bowen was ’strict and rigid and pound-of-flesh and letter-of-the-law,’ and therefore unlikely to let a criminal escape the consequences of his acts for sentimental reasons. Most dangerous of all, for me, was the possibility that he’d been having an affair with Mrs. Foley prior to Foley’s death: in that case, she would in a sense have been blackmailing him.

“No, I won’t pretend there was anything waterproof about my ideas, in this instance; the balance of probability was in favour of them, and that was all. Even as it is, I take it that the evidence against him—”

“Won’t be strong enough for prosecution,” Best put in. “No, you’re right about that, I’m afraid: after all, it’s basically only her word against his. On the other hand, these deductions you made might help a bit.”

“Not waterproof enough, as I said. He can always plead that he simply overlooked the particular bit of evidence that proved Mrs. Foley guilty—and you can’t condemn a man for that. After all, Best, you overlooked it yourself.”

“Damn me if I know what it is yet,” said Best a shade grimly. “Come on, sir, don’t be a tease: let’s have it.”

For answer, Fen ran his eye over the books ranged on Best’s mantelpiece. Rising, he crossed the room and took one down.

“Listen to Gross,” he commanded, searching through the pages. “Here it is: Hans Gross, Criminal Investigation, Third Edition, page 435, footnote. ‘To say that footgear is the only thing a corpse does not lose easily through the action of water is inadequate;—the author has never been able to believe it is ever lost. Bodies often make horrible journeys, especially in swiftly flowing mountain streams, over boulders and trunks of trees, and thereby occasionally lose whole limbs. But if the feet are kept intact, and if the corpse has on boots or shoes, not mere sandals, these are never lost; the foot swells, the leather shrinks, and so the footgear “fits uncommonly tight.”’”

Fen replaced the volume on the shelf. “All of which rather makes hay of Mrs. Foley’s story,” he observed. “According to her, Foley was pushed into the river while in the act of kicking her with hobnailed boots; yet his body was eventually recovered without—to quote you again—’a stitch of clothing on it anywhere.’ So either Mrs. Foley was lying or Gross is—and I know which of them I’d put my money on. What I think must have happened is that Foley assaulted his wife and then went into the cottage and took off his boots; whereupon Mrs. Foley seized a poker, or some such thing, and very justifiably knocked him unconscious with it, subsequently dragging him to the river-bank in his stockinged feet (possibly with the help of the faithful idiot, and possibly under the impression that he was already dead), and there shoving him in and leaving him to drown. However, she’ll give us the details herself in due course, no doubt.”

Best was sobered. ‘Yes, I certainly ought to have remembered my Gross,” he said. “And I see now what you mean about the Thames police and the Navy and the text-books, in connection with Bowen: the boots business’d be the sort of detail he really would know, with that background.”

“I was banking on that, yes,” said Fen. “And when I saw the panic in his eyes—his eyes, not hers—at my mention of the boots, I knew my guess about the blackmail was right: knew that he’d realised her guilt as soon as the body was recovered, and was putting a price on his silence and protection. It was just chance, of course, that he happened to be personally in charge of the case. But once he was in charge of it, his position was pretty well impregnable: since even if any of his subordinates had wondered about the boots, they’d have assumed there was some perfectly good explanation which he knew of and they didn’t—and in any case, they’d have thought more than twice about voicing suspicions against that particular quarter…”

Fen sighed. “Hence my interference. And now what are we left with?”

“Bowen will have to resign,” Best told him. “That’s the least that can happen. And there’ll be a charge of manslaughter—murder, perhaps—against her.”

“She’ll get off lightly, though.” Fen spoke with confidence which the event was to justify. “And when she comes out, I’ll make a point of doing anything for her that I can… I say, Best, do you think she’d have preferred the other thing—Bowen, I mean?”

“You heard the way she accused him, sir,” Best pointed out. “If you ask me, she wasn’t looking forward to their friendship one little bit… No, sir, you can make your mind easy as regards that matter, I’m sure. I wouldn’t be knowing if a certain fate’s really worse, as they say, than actual death. But if I was a woman—well, sir, as between Bowen and a couple of years in Holloway, I know which I’d choose.”

“Lacrimae Rerum”

“You chatter about ‘the perfect crime,’” said Wakefield irritably, “but you seem incapable of realising that it isn’t a topic one can argue about at all. One can only pontificate, which is irrational and useless.”

“Have some more port,” said Haldane.

“Well, yes, I will… The perfect murder, for instance, isn’t known to be a murder at all; it looks like natural death, and no suggestion of foul play ever enters anyone’s mind. Only the imperfect murders are known to be murders. And consequently, to argue about ‘the perfect murder’ is to argue about something which you cannot, by definition, prove to exist.”

“Your logic,” said Fen, “isn’t exactly impeccable.”

Wakefield gazed at him stonily. “What’s wrong with my logic?” he demanded.

“Its major premise is wrong. You’ve gone astray in defining the perfect murder.”

“I have n—How have I gone astray?”

“The sort of thing you suggest—the apparently natural death—has one disadvantage from the murderer’s point of view.”

“And that is?“ Wakefield leaned forward across the table. “That is?”

“At the risk of boring you all, I could illustrate it.” Fen glanced at his host and his fellow guests, who nodded a vinously emphatic approval; only Wakefield, who hated losing the conversational initiative, showed any sign of restiveness. “What I have in mind is a murder which was committed several years before the war—the first criminal case, as it happens, with which I ever had anything to do.”

“Quite a distinction for it,” Wakefield muttered uncivilly.

“No doubt. And it was certainly the most daring and ingenious crime I’ve ever encountered.”

“They all are,” said Wakefield.

“It succeeded, did it?” Haldane interposed rather hurriedly. “That’s to say, the criminal wasn’t discovered or punished?”

“Discovered,” said Fen, “but not punished.”

“You mean there was no case against him?”

“There was a cast-iron case; conclusive proof, followed by a circumstantial confession. But the police couldn’t act on it.”

“Oh, well,” said Wakefield disgustedly, “if all you mean is that he escaped to some country he couldn’t be extradited from—”

Fen shook his head. “That isn’t at all what I mean. The murderer is at the present moment living quite openly almost next door to New Scotland Yard.”

There was a general stir of interest.

“I don’t see how that’s possible,” Wakefield said sourly.

“And you never will,” Haldane told him, “if you don’t stop talking and give us a chance to hear about it… Go on, Gervase.“

“The murder I mean,” said Fen, “is the murder of Alan Pasmore, in 1935.”

“Pasmore the composer?” someone asked.

“Yes.”

“I remember it caused quite a commotion at the time,” said Haldane thoughtfully. “And then it all seemed suddenly to fade out, and one heard no more about it.”

Fen chuckled. “The authorities were over-precipitate,” he explained, “and naturally they were anxious that their shortcomings shouldn’t be advertised. Hence the conspiracy of silence…

“Pasmore and his wife were living at Amersham, in Bucks. He was forty-seven at the time of his death, and at the height of his reputation; though since then he’s sunk almost completely into oblivion, and nowadays his stuff’s hardly ever performed.

“His wife, Angela, was a good deal younger—twenty-six, to be exact. Attractive, intelligent, competent. As well as seeing to it that his house was kept like a new pin, she acted as his secretary. There was plenty of money—his, not hers. No children. Three servants. Superficially it seemed quite a successful marriage, as marriages go.

“On the afternoon of October 2nd, 1935, two visitors came to tea.

“One was Sir Charles Frazer, the conductor, who lived only a few miles away. The other was a wholly unimportant young man called Beasley, who worked at an insurance office in the City. Both of them, it appears, were to some extent infatuated with Angela Pasmore. Sir Charles was there by invitation; Beasley just ‘dropped in.’ And neither of them was pleased to find the other there, since at tea-time, if she were at home at all, you could be sure of having Angela to yourself. Her husband always worked from two to six in the afternoon and had his tea alone in the study upstairs.

“At four o’clock, then, tea was served in the downstairs drawing-room to Angela, to Sir Charles, and to Beasley. Five minutes later the afternoon mail arrived. It was taken from the postman at the front door by Soames, the manservant, who carried it straight to the drawing-room and gave it to Angela. It consisted of a card for Soames, several letters and cards for Angela, and a single type-written envelope for Pasmore. This last Angela immediately opened. She glanced through the letter inside and then handed it, with a slight grimace, to Sir Charles.”

“And why,” Wakefield inquired, “did she do that?”

“The letter,” Fen continued unperturbed, “was from another conductor—Paul Brice, to be specific. He was in Edinburgh (where, as it was afterwards proved, this letter had been posted on the previous afternoon), and there, at the Usher Hall in two days’ time, he was scheduled to conduct the Hallé Orchestra in a concert whose programme included Pasmore’s symphonic poem Merlin. Merlin was at this date quite a new work. It had had only one performance so far, under Sir Charles Frazer at the Queen’s Hall. And since the score was tolerably complicated, Brice wanted advice from the composer on a good many points of interpretation.

“That was what his letter was about. I’ve seen it, and it consisted of a long list of things like: ‘At 3 after C, can I relax tempo in the bar and a half before the B entry?’ and: ‘At 5 before Q, string accompaniment and clarinet solo are both marked p, but clarinet doesn’t come through; pp accompaniment would blur harmonic texture; can clarinet play mf?’ and: ‘At 7 after Y, do you want the più mosso as in the exposition?’ There were, I think, at least two dozen such queries. Conductors aren’t normally so conscientious, but Brice and Pasmore were lifelong friends, and Brice took Pasmore’s music rather more seriously than its actual merits warranted.

“You will understand now”—and Fen eyed Wakefield with a certain severity—“why Angela should show this letter to Sir Charles. Having conducted the first and only performance of the work in question, he might be expected to be interested. He read the letter attentively, commenting, uncharitably one gathers, on Brice’s artistic perceptivity. Then he gave it back to Angela.

“She in turn handed it to Soames, who was still hovering in the background, and told him to take it up to her husband with his tea, which by immutable custom was served to him at four-fifteen. This he did, testifying subsequently that at four-fifteen Pasmore was alive, uninjured and in every way normal.