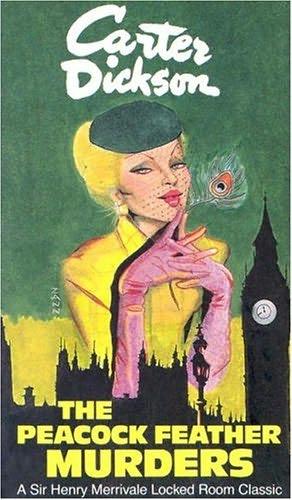

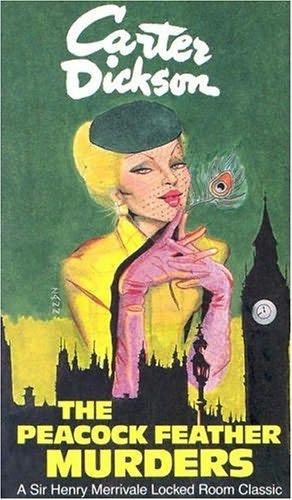

The Ten Teacups

(The Peacock Feathers Murder)

By

John Dickson Carr

1937

Writing as Carter Dickson

CHAPTER ONE

Peacocks' Feathers

THERE WILL BE TEN TEACUPS AT NUMBER 4, BERWICK TERRACE, w8 ON WEDNESDAY, JULY 31, AT 5 P.M. PRECISELY. THE PRESENCE OF THE METROPOLITAN POLICE IS RESPECTFULLY REQUESTED.

ON THE surface there would appear nothing in this note, addressed to Chief Inspector Humphrey Masters at New Scotland Yard, capable of giving Masters any uneasiness. It arrived in the first post on Wednesday, that day when the diabolical heat-wave - you may remember it - had reached its height. The note bore no signature. It was typed in the center of a stiff sheet of notepaper. To young Sergeant Pollard, Master's aide-de-camp, it was an additional pin-prick in this day of heat.

"You don't say so," commented Pollard, not without sarcasm. "If they're inviting everybody, it must be rather a large tea-party. What is it, sir? A joke or some kind of advertisement?"

He was certainly not prepared for the effect of the note on Masters. Masters, who always wore heavy blue serge and a waistcoat no matter what the weather, was stewing and sweating at a desk of papers. His big face, bland as a cardsharper's, with the grizzled hair brushed to hide the bald spot, now shone with increasing redness as he looked up. He swore.

"What's wrong?" asked Pollard. "You don't mean to say-?"

"Now, now," growled Masters. When harassed, he had a habit of assuming the air of a parent rebuking an idiot child. "Don't you go making remarks, Bob, before you know what it's all about. When you've been in this game as long as I have. . . . Here. Nip out and get me the file marked Dartley. Look sharp about it, now."

The file bore a date two years back. Pollard did not have time for a look at it before he returned; but he saw by its heading that it was a murder case, and his boredom was stirred by curiosity. So far Pollard, who had crept into the Force by way of Cambridge, had found nothing but the dullness of secretarial duties. Even his term of service as a uniformed policeman had consisted chiefly of making mesmeric passes at the traffic and arresting just 1,322 motorists. But he was interested by Masters's ominous throat-clearings as the chief inspector glowered at the report.

"Anything-exciting?" he prompted.

"Exciting!" said Masters, with rich scorn. Nevertheless, cautious as Masters was, he could not help going on. "It's murder, my lad: that's what it is. We never caught the bloke who did it, and it's unlikely we ever shall. And I'll tell you something else: I've been twenty-five years at this job, and it's the only murder I ever heard of that didn't mean anything at all. Exciting!"

Pollard was puzzled. "Didn't mean anything at all?"

"That's what I said," agreed Masters, and came to a decision. "Get your hat, Bob. I want a minute with the Assistant Commissioner on the phone. Then we're going to pay a little visit to a man you know-"

"Not Sir Henry Merrivale?

"Why not?"

"For God's sake, sir, don't do it!" urged Pollard. "Not on a day like this. He'll be wild. He'll tear us limb from limb and dance on the pieces. He-"

Despite the heat, a faint grin began to creep over Masters's face.

"Lummy, yes; the old man'll have his back up right enough," he admitted. "He's really been working, too, for a change. But you leave him to me. The thing to do is hook him, Bob; hook him. Hurrum. Then, once you've got his interest "

Masters was his usual affable self when, ten minutes later, he pushed open the door of H.M.'s office up five flights of stairs in the old rabbit-warren of a building at the back of Whitehall. Here the heat was thick with a smell of old wood and paper. From beyond the door a querulous voice was upraised; H.M. seemed to be dictating letters. Masters pushed open the door without bothering to knock, and found H.M. sitting at his desk, his feet on the desk and his collar off, staring vindictively at the telephone.

"Takeumletter," rumbled H.M., with something of the intonation of an Indian Chief. In fact, despite the glasses pulled down on his broad nose, the woodenness of his face gave him much the air of an Indian Chief: an effect heightened by his grimly-folded arms. His bald head showed against the light of the windows, and his big bulk seemed compressed by the heat.

"To the Editor of the Times, Dear Stinker," pursued H.M. "I got a complaint to make, I have, about the leprous and hyena-souled b.b.'s who have the dishonor to compose our present Government. How long, I ask you, sir . . . (that's got a good Ciceronian flourish, ain't it? Yes; I like that; you keep it in). . . How long, I ask you, sir, are free-born Englishmen goin' to stand the spectacle of public money being wasted on trifles, when there's such a blistering lot of things worth spending money on? Take me, for instance. Five flights of stairs I got to walk up every day of my life, and why? Because the dirty, low-down misers refuse to install-"

"Ah, sir," said Masters affably.

H.M., though checked in violent mid-flight, was too weary even to roar. "All right,"- he said, blinking evilly. "All right. I might have known it'd be you, Masters. My cup of trouble is now full. You might as well come in and slop it over. Bah."

"Morning, Miss Ffolliot, said Masters gallantly.

Lollypop, H.M.'s secretary, is a dazzling blonde with paper cuffs. At their entrance she got up, closing a notebook which Pollard observed to be serenely blank, and whisked out of the room. Wheezing laboriously, H.M. removed his feet from the desk. In front of him lay a palm-leaf fan.

"To tell you the truth," volunteered H.M., suddenly lowering his defenses, "I been looking for something interesting. These diplomatic matters give me the hump. Somebody's been shootin' at our battleships again. Ain't that Bob Pollard with you? Ah, I thought so. Sit down, Masters. What's on your mind?"

This easy capitulation staggered even the genial Masters. But, Pollard suspected, H.M. had actually been compelled to work for the past few days, and he was looking for any way out. Masters pushed across the table the note about the ten teacups. H.M. studied it sourly, twiddling his thumbs.

"Oh, ah," he said. "Well, what about it? Are you goin'?"

"I am," said Masters grimly. "What's more, Sir Henry, I mean to put a cordon round number 4 Berwick Terrace that a snake couldn't get through. Just so. Now look at this."

From his brief-case he took the Dartley file; and, from among the pages of the file, another sheet of notepaper. This sheet was about the same size as the first, and it was also typed. When he put the two side by side on H.M'.s desk, Pollard read:

THERE WILL BE TEN TEACUPS AT NUMBER 18, PENDRAGON GARDENS, W8, ON MONDAY, APRIL 30, AT 9:30 P.M. THE POLICE ARE WARNED TO KEEP AN EYE OUT.

"Not quite so gen-teel as the other one, is it?" said H.M.' He eyed the two notes, and frowned. "Both houses in the Kensington district, though. Well?"

"This note about Pendragon Gardens we'll call Exhibit A," Masters went on, tapping it. "It came to the Yard, addressed to me, the afternoon of April 30 two years ago. Now, I ask you, sir," growled Masters, overflowing with bitterness, "what could I do? Eh? Beyond what I did, that is. But that was the beginning of the Dartley murder case, if you remember it?"

H.M. did not speak, although his fish eyes opened a little. But he picked up the palm-leaf fan, and pushed a box of cigars across the desk.

"I've been too long at this job," Masters went on, squaring his elbows, "not to know there're good tips to be had from things like that. Eh? But, beyond passing on word to the district police-station, there wasn't much I could do. I looked up number 18 Pendragon Gardens. Pendragon Gardens is a quiet, rather posh street in West Kensington. Number 18 was an empty house-only vacated within a week or so, though, because the light and water hadn't been cut off. The only thing I could find out about it was that, for some reason, people seemed to be afraid of the place and didn't live long there. Have you got it straight, sir?"

"You're a model o' clearness, son," replied H.M:, looking at him curiously. "Ho ho! I'm just wondering whether your old bogy is goin' to sneak up and bite you ..."

"Now don't mix me up!" said Masters. "I was telling you. Hurrum. The constable who had the night-beat past there didn't notice anything odd about the place. But next morning, about six o'clock, a sergeant on his way past to the police-station saw that the vestibule door of number 18 was partly open. He went up the steps and through the vestibule, and found that the house-door was unlocked. And that wasn't all.

Though it was an empty house, there was a strip of carpet laid down in the hall; and a hat-stand, and a couple of chairs. The sergeant started looking into the rooms. There wasn't a stick of furniture in any of 'em - except one. This was the room to the left of the door on the ground floor, sort of drawing-room. The shutters were up on the windows, but the sergeant could see it was furnished.

"Just so. It was furnished right enough: carpet, curtains, and all. Even a new bowl of a chandelier. It was all ordinary stuff, except for one thing. In the middle of the room there was a big round table. On it somebody had arranged in a circle ten porcelain teacups and saucers. There weren't any tea-things; just the cups, and all the cups were empty. The cups ... well, sir, they were a bit odd. But I'll explain about that in a minute, because they weren't the only odd thing in the room. There was a dead man as well."

Masters drew a long breath through his nose. His ruddy face had a smile of skepticism, though he seemed to pride himself on his conscientiousness as well as his dramatic effect.

"A dead man," he repeated, spreading out more papers. "I've got a picture of him here. He was a little oldish man in evening clothes, with a light topcoat over 'em. (His top-hat and gloves were on a chair at the other side of the room.) He was lying on his face beside the table, between the table and the door. He'd been shot twice from behind with a .32 caliber automatic-once through the neck and once through the back of the head. Both shots had been fired at such close range that the murderer must have held the pistol directly against him: the hair and neck were burnt by it. It looked as though the old chap had been walking up to the table, maybe to look at the teacups, and the murderer had jammed the gun against him and let go. According to the medical evidence, he had been killed between ten and eleven o'clock the previous night.

"Clues? Yes. But there weren't any. There were plenty of fingerprints in the room, including some of the dead man's; but there were no prints at all on the cups and saucers, not even a glove-smudge or the mark of a cloth to wipe 'em. Nobody had smoked or taken a drink; no chairs were pulled up; there was no hint of how many people might have been in the room or what they might have been doing. There was only one other indication. A wood fire had burnt out in the fireplace; in the ashes were found the remnants of a very large cardboard box, and fragments of a piece of burnt wrapping-paper. However, they were not the box and paper in which the teacups had been packed. The container of the teacups, as I'll explain, was much more elaborate, a wooden box. But that wooden box had disappeared."

From the dossier Masters produced a photograph of a thin, mild face, with a hooked nose, a cropped gray beard and mustache.

"It was easy to identify the old boy," Masters went on. "And then-bang! A blank wall if I ever saw one. Lummy, sir, he was the very last person in the world anyone would have murdered! His name was William Morris Dartley. He was a bachelor, very well off, and he had no relatives except an unmarried sister (formidable old party) who kept house for him. It wasn't only that he hadn't any enemies; but he hadn't even any friends. It was true that in his early years he had been suspected of a business deal or two involving something like blackmail; but that was all over decades gone. His sister said (and, by George, I believed her!) that she could tell me what he had been doing every minute for the past fifteen years. Motive? Half his money went to the sister, and the other half to the South Kensington Museum. As the sister was playing bridge, with a cast-iron alibi-we never seriously considered her, anyway - there was nobody to suspect. The last tenants of the house were a Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy Derwent: Derwent being a solicitor of such painfully straight life, and the couple having no more to do with Dartley than the man in the moon, it was a dead wall again. Dartley's only interest in life, then, was collecting all sorts of art objects, with a strong preference for pottery and china. And so we come to those ten teacups."

Masters leaned forward and tapped the desk with an impressive air.

"Well, now, sir, I'm not what you'd call a connoisseur. Objay dart are a little out of my line. But one look at those cups, and even I could tell they were something special. The cups had a design on them like peacocks' feathers, all twisted up; it was in orange and yellow and blue; soft and shinylike, and it seemed to move. Also, they were very old. You could almost see 'em shine in the room. And I was right about their being good. Here's a report from the South Kensington Museum:

The cups and saucers are some of the finest examples I have ever seen of early Majolica work from Italy.

They are from the workshop of Maestro Giorgio Andreoli of Gubbio; they bear his signature and the date, 1525. But these cups, so far as I am aware, are unique. They are not, of course, teacups since tea was not introduced into Europe until the middle of the seventeenth century. I confess that their use puzzles me. At the moment my conjecture is that they were meant for some ceremonial rite, such as in the secret councils once known at Venice. They are very valuable, and at auction would probably bring two or three thousand pounds.

"Uh-huh," said H.M. "It's a lot of money. But it sounds promisin'."

"Yes, sir; I thought so, too. And we traced the cups first shot; they belonged to Dartley himself. It seems he'd bought them only that afternoon, the thirtieth of April, at Soar's, the art dealers, in Bond Street. He bought them from old man Soar himself, making a great secret of the transaction, and paid twenty-five hundred in cash. Now, then, you'd say there was a sign of a motive, even if it was a crazy motive. Suppose some crackpot of a collector wanted those cups, and went through a lot of elaborate flummery to get 'em? It don't seem reasonable, I admit; but what else was there to think?

"It was elaborate, right enough. There were the furnishings, to begin with. We found out that two days before, April the twenty-eighth, an anonymous note had been delivered to the Holborn office of the Domestic Furnishing Company-that's one of those big places where you can

equip your whole house, from lightning-rods to curtains, at one go-and the letter enclosed twenty five-pound notes. It said that the writer wanted their very best furniture for one drawing-room and a hallway. It said to get the furniture together in one lump, and it would be called for. Well, it was called for. The Cartwright Hauling Company received another anonymous letter, inclosing one fiver. This letter instructed them to send a furniture-van to the Domestic Stores, pick up a load for 18 Pendragon Gardens (a front-door key was inclosed, too), carry the load there, and shove it inside the door. It was all done without anybody getting a look at the man who'd ordered the stuff. The furniture men simply piled it all in the hall; there was nobody at the house. The chap behind it all must have arranged the furniture afterwards. Some of the neighbors noticed it being put in, of course. But, since the house was empty, they just supposed a new tenant was moving in, and thought no more of it."

H.M. seemed bothered by an invisible fly.

"Hold on," he said. "The anonymous letters - were they hand-written or typewritten?"

"Typewritten."

"Uh-huh. Same machine, was it, that wrote the letter to you tellin' you there'd be ten teacups at the place?"

"No, sir. It was a different machine. Also-what's the word I want?-a different style of typing. The ten-teacup note, as you can see, is bumpy and clumsy. The other two were clear, smooth copy. You can always tell a practiced hand at the typewriter."

"Uh-huh. Carry on."

Masters was dogged. "Now, the-hurrum-the inference," he said, "the inference we were supposed to draw is this: the murderer has baited a kind of trap. Eh? He's got an empty house and pretends it's his own; he furnishes the only parts of it a visitor will see. Dartley walks into it with the ten teacups under his arm, and for some reason is murdered. Maybe to steal the teacups.

"So far, it strings right along with Dartley's behavior. On the night he was murdered, he left his house in South Audley Street at half-past nine. His sister bad already gone out to play bridge, being driven in their car; but the butler let him out and spoke to him. He was carrying some sort of biggish box or parcel wrapped up in paper, such as might have contained the teacups. But he didn't say where he was going. He picked up a taxi outside his house: we found the taxidriver later. He was driven straight to 18 Pendragon Gardens." Masters grinned heavily. "The taxi-driver remembered him all right. Bit of luck, that. The fare to Pendragon Gardens was three and six, and Dartley handed the driver twopence as a tip. He seems to have been a bit of a tight-fisted old beggar, for all his money. But here's what isn't luck. The driver was so disgusted that he slammed in his gears and tore off without even noticing where Dartley went. Lummy, if he'd only caught a glimpse of someone opening that door! Bah. All the driver remembers is that there didn't seem to be any lights in the house."

Masters made a broad gesture.

"And that's every bit of evidence we've got. Everything else ended in a damnation full stop. No irregularities, no enemies, no anything. If you say he was, um, lured," said Masters, uncomfortable at the melodramatic word, "if you say he was lured into that house and murdered for the teacups ... well, sir, I dare say that's easiest. But it isn't sense. Like this! Now, the murderer can't be penniless. He certainly went to a lot of trouble and expense to bait his trap: anyhow, he sent a hundred quid to a furnishing company, when my daughter's furnished her 'ole blooming house for that much. If he can afford to chuck it about like that, why didn't he simply go and buy the cups from the art-dealer? 'Tisn't as though they were museum-pieces. Finally, since he'd gone to all the trouble of setting a stage and murdering Dartley, why didn't he pinch the cups? There they were, large as life, on the table. Plainly and literally, sir, they hadn't even been touched: there wasn't a fingerprint on 'em.

"I told you we'd got a fine crop of fingerprints, including Dartley's, but that led nowhere. They all belonged to the furniture-movers. The murderer must have worn gloves all the time. But he didn't take the cups? Why? He wasn't scared off, because there wasn't a sign of disturbance there all night. And there you are. It won't work however you look at it; it won't make sense; and, if there's anything that puts the wind up me, it's cases that don't make sense. For what does this murderer do on top of it all? He don't touch the cups - but he does walk off with the box that contained the cups, and the paper that was wrapped round it! I ask you, now! And this morning, two years later, I get another note about ten teacups. Does it mean more murder? Or what do you make of it?"

CHAPTER TWO

Policeman's Lot

FOR A TIME H.M. remained blinking at the desk, twiddling his thumbs over his paunch. The corners of his mouth were drawn down as though he were smelling a bad breakfast egg. It was very quiet in the room; the dusky light quivered in heat-waves past the windows. Again H.M. reached after the cigar-box. This time he took out a cigar, bit off the end, and expectorated it in a long, violent parabola of a shot which almost reached the hearth across the room.

"If you ask me whether I think it's bad," he said, sniffing; "yes, I do. I smell the blood of an Englishman again. Burn me, Masters, you manage to get tangled up in some of the goddamnedest cases I ever heard of. All we need to do is get another murder with an impossible situation that couldn't have happened, and you'll be right in your element. Yes, I can feel it comin'."

Masters, still suave, knew how to prod his man.

"Of course, sir, I can't expect too much," he said. "It isn't to be expected that you would see any light when our whole organization has been stumped for two years. Excuse me: after all, you're only an amateur. But, even if it is beyond you"

"You want to bet, hey?" demanded H.M., galvanized: He howled about ingratitude to such an extent that Pollard feared Masters had gone too far; but when H.M. was somewhat smoothed down Masters remained as bland as ever. "It seems to me," said H.M. malevolently, "that people are never happy unless they're tellin' me what an outworn, cloth-headed, maunderin' old fossil I am. It's persecution, that's what it is. All right. You watch. Just to show you this business ain't nearly as opaque as you footlers seem to think, I got a couple of questions to ask you. But there's somethin' else to decide first."

He pointed towards the note that had arrived this morning.

"Look here, son. 'Number 4 Berwick Terrace, at 5 P.M. precisely.' Why in the afternoon, anyway? There's somethin' fishy about the sound of it. I don't mean it's a hoax or a have: only that there's a queer and fishy element about it. That ending, 'The police are warned to keep an eye out,' on the note you got two years ago-that's straight and square. But, 'The presence of the Metropolitan Police is respectfully requested,' -that's unnatural, and I don't like it; it sounds like somebody laughing. I say, I hope you've had the sense to make sure it's not a hoax? I mean, you've found out whether 4 Berwick Terrace really is an empty house, suitable for polite murder?"

Masters snorted. "You can bet I have, sir. I've phoned a request to the divisional inspector for the Kensington district to get me a report on the place, and anything that's known about it. But it reminds me. He ought to have some news by this time. If you'll excuse me-?"

He leaned forward and picked up H.M.'s telephone. Within a minute he was put through to Inspector Cotteril, and Pollard heard the telephone talking sharply. Masters put his hand over the mouthpiece and turned back to them. His face was less ruddy and his eye looked wicked.

"Right," he said to H.M. "It's an empty house. It's been empty for a year or so. There's a board up in the window; Houston & Klein, St. James's Square, are the agents. Cotteril says Berwick Terrace is a little cul-de-sac: very quiet, sedate, hardly a dozen houses in it. Mid-Victorian solidness and respectability: you know. But number 4 isn't the only unoccupied house. Only a few houses in the street are occupied."

"So? What's the matter? Plague?"

Masters consulted the telephone again. "Very nearly as bad, it seems," he reported. "They're extending the Underground, and they mean to run a branch with an Underground station that'll be almost at the entrance to Berwick Terrace. It isn't finished yet, but it's on the way. The inhabitants of Berwick Terrace were so outraged at the idea of their privacy being invaded with a tube station that they moved out almost in a body. Real-estate values have dropped to blazes.

“What's that, Cotteril? Eh? Yes; that's done it." When Masters turned round again he was very quiet. "A constable on the beat there reports that yesterday some furniture was delivered to number 4 in a van, and put inside."

H.M. whistled.

"It means business, son," he said. "This murderer's got his nerve right with him."

"He'll have to be an invisible man," said Masters, "if he thinks he can get away with the same sort of funny business twice, and twist our tails as well. I'll give him ten teacups! Hullo!-Cotteril? This may be the Dartley case all over again; we can't tell yet. Send your two best men, plain clothes, and cover that house front and back. Get a man inside if you can, but keep it watched. I'll get the keys of the place from the house-agents. We'll have men inside and out. Yes: straightaway. But tell the outside men to keep out of sight as much as they can. Right. See you soon. 'Bye."

"Now, now," urged H.M. soothingly, as Masters put back the receiver with some violence. H.M. had managed to get his cigar lighted, and the smoke hung round his head in an oily cloud. "Keep your shirt on, son. It's only noon now. Grantin' that the murderer sticks to his schedule, you got five hours yet: though I admit you'd be pretty simple-minded if you accepted his word without question. Humph."

"Doesn't it bother you at all" inquired Masters.

"Oh, sure. Sure; I'm bothered as hell. And it's this fellow's method that bothers me, Masters, and why he happens to be so cocky about it. But I'm not very grief-stricken as yet; because, the trouble is, we haven't got the foggiest notion who has been chosen as a victim."

"Excuse me, sir," interposed Pollard, "but how do you know murder is intended at all?"

There was a pause. Both the others looked at him. Masters turned round a lowering eyebrow, and seemed about to say, "Now, now," in that heavy fashion he reserved for juniors: especially any juniors with what he called "your education." Though Masters was easy to work for, he was a terror to speech. But Pollard had been too interested by that queer picture-the ten teacups, painted with a design like peacocks' feathers, ranged in a circle and shining among commonplace furniture.

"Go on, son," said H.M. woodenly. "What's on your mind?"

Pollard reached out and tapped the notes. "It's these. Neither of the notes actually makes a threat or suggests trouble of any kind. What they do say is that there will be ten teacups at such-and-such a place. Suppose the murder of Dartley was only a slip in the plan? .. Like this, sir. We've got only one indication as to what the cups might mean. That indication is in the report from the man at the South Kensington Museum. Here it is. `My conjecture is that they were meant for some ceremonial rite, such as in the secret councils once known at Venice.' I don't know anything about secret councils at Venice. But at least it's a lead. I mean - suppose it's a meeting of some secret society?"

"H'm," said H.M. "Sort of Suicide Club, you mean? Only this seems more like a murder club."

"Won't do, snapped Masters. "Now, Bob, we've been over all that before. All of it. The idea of a secret society was suggested at the time of Dartley's death. It was some newspaper idea; they printed a lot of high-colored feature articles about secret societies old and new. And it's bosh. To begin with, if it's a secret society, it's so ruddy secret that nobody else ever heard of it."

"I dunno," said H.M. "You got a simple straightforward mind, Masters. Your idea of a secret society is one of the big benevolent orders, which really aren't secret societies at all in the sense I mean it. There are deeper places than that, son. Seems like you can't believe in a secret society that really is secret, and that's run without fuss. Mind you, I don't say it's so in this case. I doubt it myself. But have you got any reasons for swearin' it couldn't be so?"

Masters was dogged. "Yes," he declared. "III give you one good practical reason: Dartley's sister Emma. That woman could have made her fortune at private detective work. I never saw such a nose for snooping before or since. She swears there wasn't, and couldn't have been, anything like that; and - well, I'd back her judgment. If you met her you'd understand. What's more, we had the whole organization after that lead. And there wasn't a scrap of evidence anywhere to support it. All the signs showed that only two people had been at Pendragon Gardens that night: Dartley. and his murderer. Now, sir, I don't know whether you can run a secret society without any fuss. But I'm smacking well certain you can't run one without any members."

H.M. surveyed him.

"You're gettin' out of hand," he said. "But let's stick to facts, if you like it better. You brought up Dartley again, and it's Dartley I want to ask about. He had a pretty big collection, had he?"

"A big collection, and a valuable one. Close on a hundred thousand pounds' worth of stuff, the man from the museum said."

"Uh-huh. What was it, mostly? Pottery?"

"Pottery, yes, but a lot of other stuff as well. I've got a list here somewhere. It was a pretty mixed bag: some pictures, and snuff-boxes, and books, and even a sword or two."

"Did he deal much with Soar's in Bond Street?"

Masters was puzzled. "Quite a good deal, I understand. He was friendly with old Benjamin Soar-you remember, the head of the firm who died about six months ago? Soar's son runs the business now. I remember, the man from the museum said Dartley must have been an uncommonly shrewd businessman, for all his mild looks. There was a packet of receipted bills in his desk, and he'd beaten down Soar to a very good price on a lot of the stuff." Masters looked at H.M. shrewdly. "Not, of course," he prodded, "that it's important..."

"Oh, no. Now, when Dartley bought the teacups, how were they packed?"

"Ordinary big teakwood box about two feet long by one foot deep; nothing out of the way. They were packed inside in tissue paper and excelsior. The box was never found, as I told you."

"Just one more question, son; and be awful careful about the answer. Now, I suppose they took an inventory of the collection after his death, if he gave it to the museum. When they went over his collection, was there anything missing?"

Masters sat up, rather slowly. His big face was half-grinning, with surprise.

"I might have known," he replied after a pause, "that you'd pull a rabbit out of the hat like that. How did you know there was something missing?"

"Oh, I was just sittin' and thinkin'. And I thought maybe there might be. What was it, son?"

"That's the odd part of it. If I remember it right, it was one of the few things in the old chap's collection that wasn't valuable. He kept it as a curiosity, like a toy. It was what they call a 'puzzle-jug.' You've probably seen 'em. It's a big jug, porcelain or what-not, with three spouts and sometimes a hollow handle with a hole in it. The spouts are on all sides. The idea is to fill it up with water and challenge somebody to pour it out one of the spouts without spilling a drop from any of the others." Masters paused, and stared. "But what in the name of sense has a missing puzzle-jug got to do with Dartley's murder, and how does it fit in with ten teacups in a circle?"

"I haven't got the foggiest idea, son," admitted H.M. He looked disconsolately at his hands, and twiddled his thumbs again. "At the moment, anyhow. But I sorta thought, from somethin' you said, that there might have been a missing item in Dartley's collection. No, no, don't ask me why! Burn me, Masters, you got work to do. You're a man of action, and it strikes me you'd better get busy."

Masters rose, drawing a deep breath.

"I mean to," he said, "straightaway. But we've got a conference at the Yard on that Birmingham business, and I've got to arrange to get away." He looked at Pollard. "You're the man to handle the first part of this, Bob. Think you can manage it?"

"Yes," said Pollard briefly.

"Right. Hop round to Houston & Klein, the house agents, in St. James's Square. Get the keys of 4 Berwick Terrace, and an order-to-view. Don't let on you're a copper: they may make trouble. Put on your most high-falutin manner and say you're thinking of buying the place. Got that? Find out if anybody else has asked for the keys. Then get into the house, find the room where the furniture is, and don't leave that room no matter what happens. I'll join you as soon as I can. Hop to it."

The last thing Pollard beard before he left the room was the sound of H.M.'s ghoulish mirth, and a noise from Masters like, "Ur!" Pollard admitted to himself that he was excited about this case; he also knew that, if he fell down on it, Masters would have his hide. Over Whitehall a sickly, darkening sky pressed down, as though there would be rain before

evening. Pollard walked so fast after a bus that he found himself in a bath of sweat, and had to re-adjust himself. But within ten minutes he was in the offices of Houston & Klein,

outstaring an imposing gentleman who bent forward confidentially across a desk.

"Number 4 Berwick Terrace," said the agent slowly, as though the name were only half-familiar to him. "Ah, yes. Yes, of course. We shall be very pleased to let you have a look at it." He regarded Pollard without apparent curiosity. "May I say sir, that that house seems to have become very popular?"

"Popular?"

"Yes. We gave a set of keys and an order-to-view to another applicant only this morning." He smiled. "Of course, the prior order entails no advantage if anyone cares to purchase-"

Pollard allowed annoyance to show in his face. "That's unfortunate. That's very unfortunate, if it was the person I think it was. Who was it by the way? There's a sort of wager...: '

"Oh, a wager," said the agent, puzzled but relieved. His hesitation vanished. "Well, sir, I don't suppose there's any particular secret about it. It was Mr. Vance Keating."

The name unfolded a whole list of possibilities. Pollard vaguely remembered having met Keating at a party, and having disliked him: but the name had a certain notoriety to any newspaper-reader. Vance Keating was a young man with a great deal of money, who too often and too publicly announced his boredom with life. "We belong," he had once said, in a speech which caused some mirth, "to the cult of the Venturers who are as old as chivalry. We ring strange doorbells. We get off at the wrong stations. We penetrate into harems, and go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Always we are disappointed; but still we believe that adventure, like prosperity, is just round the corner." On the other hand, Keating certainly had performed several very dangerous exploits; though it was rumored that his stamina was not always equal to his ideals, and that, the time he went after the twelve-foot tiger, he collapsed and had to be carried most of the way in a litter. Pollard remembered having read not long ago of his engagement to Miss Frances Gale, the golfer.

Pollard said: "Oh, Keating. Yes, I'd expected that. Well, you may expect a struggle, but one of us will get the place.... I wonder if you could tell me whether anyone else has been looking at the house recently?"

The agent considered. "I don't think there's been anybody within the last six months. I can't tell you offhand, but I can find out for you. Just one moment. Mr. Grant!" He went off majestically, and returned with records. "I find I was wrong, sir. A young lady viewed the house about three months ago: on May 10, to be exact. A Miss Frances Gale. I believe the young lady is-er-?"

"Thanks," said Pollard, and got out quickly.

If Vance Keating were mixed up in this business, then something spectacular was on the way. Keating concerned himself in no placid affairs. Sergeant Pollard went down into a sweltering Underground, rode as far as Notting Hill Gate, and then walked westward through the steep, quiet streets.

It was only a quarter past one, but the whole neighborhood looked dead. A muddy yellow sky pressed down on the heights; sometimes an air would stir like a puff out of an oven, and rattle the dry leaves of plane trees. He found Berwick Terrace easily enough. It was a cul-de-sac leading out of a larger square, a backwater as cut off as though it had gates. Berwick Terrace was about sixty yards deep by twenty yards broad. In it were ten houses, four on each side and two narrow-chested ones facing out at the end. They were solid, uniform houses in graystone and white facings; with bow-windows, areaways, and stone steps leading up to deep vestibules. Each had three stories and an attic. They had darkened to a uniform hue with soot; they were built together, and looked like one house except where railings went up to the front doors from the lone line of area-rails. But stiff lace curtains showed at the windows of only four houses-possibly that was what gave the street its desolate, gutted look, and to Pollard a feeling of disquiet. Nothing stirred there. The only sign of life was a child's perambulator in the vestibule of number 9 at the end of the street. The only sign of color was a garish red telephone-box at the beginning of the street. Otherwise the chimneys stood up dark against an uneasy sky. Once the greater part of its tenants left, Berwick Terrace had begun to decay with amazing swiftness.

Number 4 was on the left-hand side. Pollard walked down the right-hand pavement, and heard his own footsteps echo. He stopped across the road from number 4, leisurely took out a cigarette, and examined the house. There was nothing to distinguish it from the others, except that it was possibly a trifle more shabby. Some of the windows were shuttered, some were dusty, and one or two of them were now open. Just as he glanced across, Pollard thought he saw the attic window move, as someone pushed it up to look out. There was someone in the house now, and that person was watching him.

A very low voice behind him whispered: "Sergeant!"

The house before which he was standing, number 2, was also vacant. Out of the corner of his eye Pollard had seen that a window on the ground floor, beyond the areaway, was up about half an inch. The voice was coming from there, although he could see nothing because of the dust.

"Hollis, L Division," it said. "I've been here about an hour. Porter is watching the back. We've got it taped; there's no way in or out except by the front or back door.- I don't know whether it's the man you're after, but there's somebody in the house now."

Pollard, lighting his cigarette, spoke ventriloquially.

"Be careful; he's up at the window. Don't let him see you. Who is it?"

"I don't know. Young fellow in a light suit. He got here about ten minutes ago-walking."

"What's he been doing?"

"Can't tell, except that he opened a couple of windows; he'd have choked to death if he hadn't. It's hot as hell in here."

"Did you manage to get inside the house and have a look?"

"No; we couldn't. The place is locked up like a strongroom. We couldn't get in without attracting attention, and the inspector said-"

"Right. Stand by."

With a luxurious puff, Pollard strolled across the street, examining the house with open interest. He drew out the keys, to which a cardboard label bearing the agent's name was attached, and juggled them. The bow-windows to the left of the door, he noticed, were heavily shuttered; that would probably be the room where the furniture was arranged. He started up the steps to the front door. Then he glanced towards the mouth of the street, and stopped.

Berwick Terrace lay off a large square called Coburg Place. The trees of the square stood up twinkling in hot, hard light; and it was very quiet except for the sudden beating of a car-engine. A blue Talbot two-seater cruised past the mouth of the street. The driver, a woman, was leaning out of the car and peering down Berwick Terrace: intently, for the car wabbled. It was too far away for Pollard to distinguish her features, yet there was something intent and startled even about the sound of the engine. Then the car whisked away.

Pollard felt that somewhere a wheel had begun to spin, a conductor had lifted his baton, a beginning had been made in the movement of rapid and evil things. But he had no time to consider that. The inner door of the house was dragged open. There was a step on the marble tiling of the vestibule, and the vestibule door opened as well. A man stood just inside, looking at him.

"Well?" said the man.

CHAPTER THREE Murderer's Promise

THE VESTIBULE was paved with red-and-white marble flags, and it was very dark, so that Pollard had only an indistinct view of the man inside. But he recognized him as Vance Keating. Keating wore a suit of very light gray flannel, somewhat begrimed, and his thumbs were hooked in the coat pockets. He was a thin, wiry, middle-sized young man, with a long nose and a discontented mouth. Ordinarily his expression might have been spoiled or supercilious, but now it was that of excitement; he carried his own atmosphere with him. Excitement, or suspicion. Pollard saw his eyelids move to the gloom. But there was one thing about him which added an almost grotesque touch: in his excitement he had got hold of somebody else's hat. The hat was a soft gray Homburg a size or more too large for him; it was squashed along one side, and came down nearly far enough to flatten out his ears.

"Where's the woman?" he demanded.

"Woman?"

"Yes. The woman who-" Keating stopped, and in that instant Pollard was certain some secret meeting or conclave was to have been held, so that Keating had taken him for a member of it. But Keating's mind worked too; he weighed possibilities suddenly, and the opportunity for pretense on Pollard's part had gone.

"La tasse est vide; la femme attend," said Keating.

Well, there were the old melodramatics again: evidently the password to which he must supply the answer. And he hadn't got the answer. Pollard had determined on his course.

"The chickens of my aunt are in the garden," he replied.

"What about it?"

"Who the hell," said Keating in a very low voice, "are you? What do you want here?"

"I want to see the house, if it's all the same to you."

"See the house?"

"Look here," said Pollard mildly, "let's get this thing straight. I want to see the house with the idea of buying it, if the price is right. Didn't Houston & Klein tell you? I'm in the market for something like this. So I got an order-to-view, as I suppose you did."

"But they can't do that," cried the other, in a stupid-sounding voice which had a note of incredulity amounting almost to horror. It was evidently the one thing he had not foreseen. "They can't do that. They gave me the keys"

"There's no reason why we both shouldn't look at it, is there?" asked Pollard, and moved past him into the hall.

It was a good-sized hall, but very dark in the heavy-woodwork fashion of sixty years ago: a dust-trap and a shadowtrap. On the landing of the staircase a round window of very thick multi-colored glass, twisted into dingy reds and blues, gave a crooked light which barely tinted the darkness. It seemed to draw the hall together oppressively. Footsteps on the bare boards went up and were lost in echoes. As though casually, Pollard strolled across to the room on the left and opened the door.

The furniture had not been put in this room.

Though the shutters were up on the windows, he could make out that much. It surprised him, unpleasantly, for he was now looking for traps. Out of the corner of his eye he watched Keating. Granting that something ugly was on the way, the question became this: was Vance Keating the instigator or the victim?

"Sorry, old boy," said Keating suddenly. His expression had altered and shifted like an actor's, as he debated courses; and now he came forward with an air of very genuine charm. "I'm a bit on edge, that's all; late party last night. There's no reason at all why we both shouldn't look at it. I can even show you over the place, if it comes to that. Er-shall you be long?"

Pollard looked at his watch, which said one-forty. It would be three hours and twenty minutes before the threatened coming of the ten teacups.

"I'm afraid I'm early," he replied. "There'll be a lot of time to kill. You see, I arranged to meet my sister here - she keeps house for me, and naturally wants to see the place - at half-past four. But she'll probably be late at that; she usually is. I'd better not be in any hurry. Or, if you like, I can go now and come back about four-thirty or five."

Keating half turned away. When he turned back again, his face wore a look of calm superciliousness.

"I wonder," he suggested politely, "whether you'd just come along with me for a minute?"

"Come along where?"

"This way," said Keating, and marched out of the house.

Undoubtedly he had to go. Whether Keating were instigator or victim, an eye must be kept on him. But, if Pollard had any notion that Keating was attempting to lead him a dance, it was soon dispelled. Keating went no farther than the telephone-box at the corner of Berwick Terrace. Holding open the door so that the other could listen, he dialed a number.

"I want to speak," he said, in a new and supercilious voice, "to Mr. Klein. . . . Hullo: Klein? Vance Keating speaking. I've made up my mind about that place in Berwick Terrace. What was your price? ... Yes. And freehold. . . . Yes, that's quite satisfactory. I'll buy it, if-just one moment. There's another customer of yours here. Would you care, my friend, to go higher than three thousand five hundred? Ah, I thought not.... Klein? Yes, I'll buy. The deal's made now, isn't it, as soon as I make my decision? The house is mine from this minute, even before I get the deed? ... It is? You're sure of that? ... Right. Good-by."

He hung up the phone with a certain care, and stepped out of the box.

"Now, my friend," he announced with satisfaction, "I scarcely think the house will interest you any longer. I am accustomed to having what I want, and I have it now. Any further visits to 4 Berwick Terrace, social or otherwise, will be discouraged. You will therefore oblige me by getting to blazes out of here."

The gray Homburg, flattening out his ears, nevertheless sat jauntily on the back of his head. He moved away with a long, free stride, evidently having the business settled to satisfaction. His air seemed to indicate that he could now forget it. Sergeant Pollard, with an un-Robert-like wrath mounting up to his own ears, took a step after him-when he heard a familiar, long clearing of the throat from the other side of the telephone-box. Turning back, Pollard saw the boiled blue eye of Chief Inspector Humphrey Masters looking at him from the direction of Coburg Place. Masters shook his head, and beckoned.

The sergeant waited only long enough to make sure that Keating went back into the house. Then he joined Masters, whose bowler hat was looking sinister.

"We've got to teach you," said Masters, "when in doubt, never fly off the handle. I don't." His eye wandered down in the direction of the house. "Lummy, but he can afford to chuck it about! Thirty-five hundred for - what? That's what beats me. Never mind. Report."

Pollard gave a brief summary, and Masters chewed it over.

Was there anybody in the house besides Keating?"

"I couldn't tell. But I shouldn't think so, judging by the way he rushed out to meet-whoever he thought I might be, when I went to the door. He's expecting a woman, and he wants to meet her very badly."

"It's still a lot of money," Masters pointed out, somewhat obscurely. "Hurrum. And no furniture in the front room. Still, that doesn't mean anything. House is covered front and back. I tell you, Bob, nobody can get in there! 'Tisn't possible! Look here: you've got to get in, though. Sneak in, of course. You've got the keys, and you can try the back this time. If he catches you, you're for it, but you've got to see he doesn't catch you. I'll join Hollis in the house across the street."

The chief inspector reflected, rubbing his chin.

"The trouble is, as you say, that we don't know whether he's a victim or a wrong 'un. In either case we can't show our hand. If we went charging in there, and explained who we were-well, he'd simply order us out. As he's got the right to do. This is the only way. Maybe it happened for the best: there's still three clear hours before five o'clock. You get into that house, you find out which room he's in, and you stick outside that door like glue."

From Coburg Place a narrow mews ran up behind Berwick Terrace. Each house had a spacious back-garden, fenced in by a six-foot board wall. Pollard was relieved to see that all the back windows of number 4 were shuttered. As he slid through the rear gate he was challenged by Porter, the plain-clothes constable stationed in a decrepit summerhouse there.

"Not a peep out of the place," Porter told him. "I know them kind of shutters; you can't see through 'em even when you're inside. Duck up to the back porch quick, and he won't be able to spot you even if he's at the window."

The back door had an overhanging roof with iron scrollwork. Once under it, Pollard's great fear was that the door would be bolted on the inside, and that his key would be of no use. But the key opened it; and, to his surprise, the door moved almost soundlessly.

He stood in the gloom of a kitchen. The heat of dry timber came down on him like a bag over the head. Though these old floors were solid, the utter absence of life, of furniture, of .anything human and moving inside a shell, made every footstep faintly audible. He found himself walking on shaking ankles to keep quiet, and wished too late that he had had a final smoke before he entered. The plan of the ground-floor was simple: at the rear were the kitchen and the butler's pantry; then the central hall with two spacious rooms opening off it on either side. There was no stick of furniture in any of the four rooms, except a potted plant left behind in one. And Pollard, though far from psychic, did not like the look of any of them. He remembered Masters having said that number 18 Pendragon Gardens, where Dartley was murdered, had such an unpleasant reputation that nobody would live in it; and he wondered whether number 4 Berwick Terrace had a similar reputation. The house, so to speak, breathed wrong. Whoever had lived here last, the occupant had a passion for crowding the rooms with very small pictures; the walls were spotted, like a rash, with lines of tiny hooks attached to nails.

He had penetrated as far as the front room on the right, when he heard footsteps coming down the main stairs.

They were rattling, brisk, jaunty footsteps. He knew that they belonged to Keating even before he saw the man. Looking out through a crack of the door, Pollard saw Keating cross the hall, go out the front door-whistling softly to himself - and lock it behind him. Then silence came again.

Pollard put his head out cautiously. It might be a trap: after all the trouble Keating had taken to remain alone in the house, he would not presumably saunter off like this. On the other hand, he might now have devised his trappings and baited his teacups. He might have finished whatever preparations were necessary.

The sergeant risked it, and hurried up the staircase. After a few minutes' waiting, without a click from the front door or a rustle in the vestibule, he was emboldened to make a search

of the two upstairs stories. Each floor had five rooms, bed and sitting rooms, and a somewhat primitive bath. The same desolation curtained off each from the world. There had been children here, for the walls of one were papered in nursery designs; but he did not imagine they had been very happy children. And still there was no trace of the one furnished room.

It must be in the attic, unless Keating had led them all neatly astray by the nose. Pollard suddenly had a vivid remembrance of the first thing he had seen when he arrived at the house an hour ago: a figure, supposedly Keating's, peering out of an attic window. At the rear of the topmost hallway he found a door giving on a narrow flight of stairs almost as steep as a ladder....

The attic was "finished." That is to say, you emerged through a sort of trap into a hall which had been formed by wooden partitions built up to the roof on either side. These partitions appeared to form four separate rooms, for there were four doors. But it was gloomy here, and the heat had become strangling: he felt his pores stir to it. This must be the place of the teacups: though why, in sanity, should furniture be carried up to the remote top of the house when every room was vacant? Yet this front attic room-on the left as you stood facing the front-would contain the window out of which someone had been peering an hour ago.

He went to the door and turned the knob. It was locked. And it was the only locked door inside the house.

Probing into the other three rooms on this floor, he found them all open. This one garret chamber, some fifteen feet square, was the one he wanted. The key was not in the lock, and he tried to peer through the keyhole. He got an impression that the walls were of grimy white plaster; and that in the middle of the fifteen foot room there was a table covered with some cloth that looked like very dingy gold; but the rest was a blur. He investigated a faint line of light under the door, with no result except to discover that the carpet was very black and thick. There was, he felt convinced, nobody in the room now. But it stopped him. To pick the lock he found impossible, and he could not break it open without giving the show away when Keating returned....

It was two hours before Keating. returned, a time of dreary waiting during which Pollard's stolidity began to wear thin. He spent it in exploring the house, including every nook of the cellar, and making certain there was nobody hidden.

It was fifteen minutes past four when he heard Keating's distinctive step come into the house, and the slam of the front door. And Keating was alone.

Pollard went softly up to the attic, hiding himself in the rear room to the right. Through the crack of the door he had a clear view of the locked sanctuary. Keating's footfalls ascended the attic stairs, Keating's head appeared through the trap, and Keating seemed greedy with expectancy. Taking a key out of his coat pocket, he opened the sanctuary door. He was so quick about going in and closing the door after him that Pollard had only a brief, narrow glimpse of anything inside. Yet he saw the table-cover dull-gleaming, and he saw teacups ranged in a circle-black teacups. Keating did not lock the door behind him; the key remained in the lock outside. The young Venturer made only one other movement when he slipped through into this uncouth shrine; he removed his hat.

Four-fifteen. Four-thirty. Pollard felt his scalp crawl and his wits thicken under the pressure of heat. Still no sound issued from the room, nor was there a sign of any other visitor, while the watcher stood neck-cramped with his eyes on the door. The hand of his wrist-watch crept upwards: a quarter to five. And now good theories began to dissolve when he remembered Masters's words: "I don't know whether you can run a secret society without any fuss, but I'm smacking well certain you can't run one without any members." He was right. Vance Keating sat alone in the shrine, guarded if ever a man was guarded, with police at both the back and the front. Five minutes to five.

Keating screamed, and Pollard heard the first shot, just as the minute-hand of the wrist-watch stood vertical.

Scream and shot were so unexpected, the explosion so muffled as of a weapon pressed into flesh, that Pollard hardly knew what he was hearing. Then there was the slither and crash of breaking china, and a thump. Then there was the second shot, less muffled, and blasting so close at hand that it shook the key in the door. A heavy revolver had been fired twice behind that door; and, while the echoes of the shots were settling, Pollard heard his wrist-watch loudly.

He smelt powder-smoke from an old-fashioned type of cartridge even before he ran across the hall. When he opened the door of the shrine, he saw a low room with white-plaster walls. In the wall to the right was the room's one window.

Outside the sky was darkening with storm, and heavy curtains of dark velvet were partly drawn across the window, but there was light enough for him to see the round table on which were ranged the ten teacups. Two of the cups were smashed.

Vance Keating lay at full length, on the floor between the table and the door, his head towards the door. He was lying on his left side, his face pressed into the floor and his right leg a little drawn up. He had been shot twice (these were later known to be undeniable facts) with a .45 caliber revolver which lay on the floor at his left side. In the back of his skull there was a ragged black burn where a bullet had been fired into his brain. In the back of his gray coat there was another burned hole, still smoking and showing an ember against the black, where a second bullet had entered. Above the odor of powder-smoke was that of burnt cloth and hair. The weapon had been held against him, Pollard saw; blood began to come sluggishly from the wounds, but very little, for he died under the watcher's eyes.

Standing so as to bar the doorway, Pollard saw these things not as tabulated items, but of a piece. However a murderer had got in here, the murderer must still be in the room. He knew that nobody had gone out by the door. And the one window was forty feet above the street.

He thought: Steady! Take it easy! Take it easy, now....

Wiping his gummy eyelids, he reached outside, got the key, and locked the door on the inside. Then he went round the room, slowly and with senses strung alert; but he found nobody because there was nobody there. In the thick pile of the black carpet were only two sets of dusty footprints - his own, and those that led to the upturned toes of Vance Keating's shoes. Then he went to the window.

Storm was coming on; a puff of cooler air blew in his face. Serene in its doze, Berwick Terrace lay spread out forty feet below. He realized how little time had elapsed between the firing of the shots and his going to the window, when he saw the bowler-hatted figure of Masters pelting across the street towards the door of number 4. Leaning across the sill, he stared left and right along the blank facade of the house, along a large and empty street which would have shielded no fugitive.

"He got out of the window!" shouted ' Detective-Sergeant Pollard.

Across the street the ground-floor window in the house directly opposite, where Sergeant Hollis was watching, flew up with an unseemly screech. Hollis poked out an angry head.

"No, he didn't," came Hollis's voice in a faint yell. "Nobody got out that window."

CHAPTER FOUR

Lawyers' Houses

AT EXACTLY half-past five, Doctor Blaine, the brisk police surgeon, rose from beside the body of Vance Keating and dusted his knees. Photographers were at work in the room, and flash-bulbs glared. McAllister (fingerprints) stood close to the window to catch the light, with the .45 revolver on his knee, and used the miniature bellows. Doctor Blaine looked at Chief Inspector Humphrey Masters.

"Just," he asked, "what do you want to know?"

Masters removed his bowler in order to wipe his forehead with a handkerchief. Masters appeared to be suffering from claustrophobia. But he tried to achieve lightness, possibly in self-defense.

"Well, I can see he's been shot," he admitted. "But the gun, now? With that gun?"

"That's hardly my job. You'll know before long; but, all the same, I shouldn't think there was much doubt about it." Blaine pointed. "Those two wounds were made with a .45. Also, it was a very old-style gun with old-style ammunition. A modern high caliber, with steel-jacket ammunition, would have sent both bullets smack through him. And you've got the gun that fits right there, with two exploded cartridge-cases in the magazine."

He nodded towards McAllister, evidently puzzled at the black look on Masters's face. Masters went over to where the fingerprint-man was blowing the last dust off the butt, and

Pollard followed him.

In its own way the revolver was a fine piece of gun-making. Though large, it was not cumbersome, and it was much lighter than you might have expected. The silvered steel of the barrel and magazine had been worn almost black, but the handle was inlaid in curious 'designs with mother of pearl. Into the foot of the grip had been set a small silver plate engraved with the words Tom Shannon.

"That name, now," Masters considered, pointing to it. "You don't suppose-?"

"If I were you, Chief Inspector," said McAllister, with a last puff, "I wouldn't send out a bulletin after Tom Shannon. It'd be like trying to arrest Charlie Peace. Shannon has been pushing up the daisies for forty years. This gun was his. And what a gun!" He held it up. "Know what it is? It's the original Remington six-shooter, made in 1894. If you've ever read anything about the Wild West, you'll know what that means. And Shannon was one of the original bad men. I only wonder there aren't any notches in the thing; but maybe Shannon didn't like to chop up his shooting-irons. Where do you suppose anybody got ammunition for the thing, in this day and age? It's loaded except for two shots gone. Also, how did it happen to turn up in England? Probably the answer to both questions is that it belongs to somebody who makes a collection of guns

"Collectors!" said Masters. He seemed to meditate on a string of collections which included teacups, puzzle-jugs, and now six-shooters. "Never mind about that. What about fingerprints?"

"Not a print on the whole thing. The bloke wore gloves."

When Masters turned back to Blaine, he made an effort to recover some of his usual blandness.

"Point's this, Doctor. You've been asking just exactly what we want to know. And there's only one question. Is it absolutely certain, could you swear to it, that both those shots were fired with the gun held close to the body?"

"It's absolutely certain."

"Now, now, take it easy," the chief inspector urged. He became confidential. "I'll explain what I mean. This isn't the first time I've come across a situation like this, and each time I learn a new wrinkle in the way of getting out of sealed rooms. It's a kind of nightmare of mine, if you see what I mean. But it is the first time when (if your diagnosis is straight; excuse me) it's proved as certain-sure that the murderer must actually have been in the room. It's also the first time the facts could be sworn to by the police, beyond any possibility of hanky-panky. Like this!"

He tapped a finger in his palm.

"Sergeant Hollis, of L Division - and myself as well-we were in the house across the street, watching. Especially, we watched the window of 'this room. We never left off watching it. You see, this chap who's dead, Mr. Vance Keating, returned to the house at a quarter past four. A little later we saw him peep out of this window. It was the only window in the house that'd got curtains up; and we knew we'd spotted the `furnished room.' Eh? So we watched. At the same time Sergeant Pollard here-" he jerked his head-"was watching the door. And nobody went out either way. Now, then: if you tell me there's the remotest possibility the fellow might have been shot from a distance-well, everything's all right, because the window was open, and a couple of shots might have come through the window. But, if you tell me the murderer must have been in the room (and I admit I think so myself), then we're up against it."

Blaine said, "The rest of the house is dusty-we're leaving tracks all over the carpet--"

"Yes," said Masters. "I asked Pollard about that. He swears that there were only two sets of prints when he broke in - his own and Keating's."

"Then it was Keating who furnished the room?" asked McAllister.

"M'm-no-not necessarily. Broom standing in a dark corner out there. The furnisher could have swept the carpet after him. That doesn't prove anything."

"Except," said Blaine dryly, "that there was no one in the room except Keating when he was shot-unless Pollard shot him."

Masters made a strangling noise in his throat, and Blaine went on.

"What about trap-doors or thungummyjigs?" he inquired.

"Trap-doors!" said Masters. "Take a look around."

It was certainly a sort of tank. Two walls of the room, the one facing the door and the one which contained the window, were the solid stone walls of the house itself. Two wooden walls had been built up to the roof in order to form the four sides of the room. All the walls and the ceiling were covered with grimy white plaster, which showed no crevice except a few wandering microscopic cracks. From the middle of the low ceiling descended the short pipe of a dismantled gas-bracket, with a lead plug over the mouth.

On the floor, which was of solid timbers, lay a black carpet of very rich and deep pile. Against the wall opposite the door stood a mahogany chair. Against the wall to the left was a rather dingy divan. But what took the eye was the object in the middle of the room: a circular mahogany table of the folding variety, some five feet in diameter. It was covered by a square cloth of what resembled peacocks' feathers worked, in dull gold, and very slightly pulled out of line on the side towards the door. The circle of very thin black teacups and saucers had been ranged on it like numbers on a clock. Two teacups, on the side towards the door, had been smashed; but smashed in a somewhat curious way. The cups remained in the cracked saucers; the pieces had not been knocked wide, and lay in or close on the saucers; it was as though some heavy object had been dropped flat on them.

"The last place you'll find trap doors," said Masters, "is bare plaster. Look here, doctor: we're going to catch ruddy hell for this. Here we are, smack on the scene of the crime like a lot of mugs, and still! That's why, if you could show the shots weren't fired in this room-?"

"Well, they were," retorted Blaine. "Your own ears ought to have been able to tell you that. Hang it all, didn't anybody hear them?"

"I did," volunteered Pollard. "I wasn't a dozen feet away from the door, and I'm willing to swear the shots came from here."

Blaine nodded. "Now take a look at the head-wound first. The pistol was held about three inches away from the head; it was a soft-nosed bullet, and it split the skull up badly. You can see the ragged singeing of powder-marks from an old-style cartridge. That other bullet, in the back-it broke the fellow's spine, poor bastard. The gun must have been jammed directly against him. You must have been in here pretty quick, sergeant. Didn't you notice any signs?"

"Plenty of them," replied Pollard, facing vivid memory. "The cloth was still burning; I saw sparks. And there were smells. Also smoke."

"I'm sorry, Masters," said Blaine. "There's no doubt whatever."

There was a silence. The photographers had gathered up their apparatus and had gone out. From the street ascended the murmur of a crowd, and the voice of a policeman ordering them on; the halls of number 4 Berwick Terrace were alive with trampling feet, where inspector Cotteril had charge; and in the center of the web Masters prowled round the room pounding at the walls with his fist. He addressed McAllister, who was also prowling.

"Finished?"

"Just about, sir," said the fingerprint man. "And it's the barest den of iniquity I ever got into. There's not a print in the place, bar a few blurred ones on the arms of that chair and a few clear ones on the window-frame-but I'm pretty sure they were all made by the dead man."

"Nobody touched the table or the teacups?"

"Not unless they wore gloves."

"Oh, ah. Gloves. It's the Dartley case all over again, with fancy trimmings. Lummy, how I hate cases that aren't sense. Right, McAllister; that's all. You might ask Inspector Cotteril if he'll come .up here a moment. And thanks, Doctor; that's all for you. I'd be glad if you'd do the PM as soon as possible; we want to be sure about that revolver. But I don't want the body removed for just a minute yet. First I want to go through the pockets. And then there's a gentleman coming here presently ... hum . . . name of Sir Henry Merrivale; and I want Sir Henry to see him."

When Blaine had gone, Masters prowled once more round the table, peering.

"Flummery," he said, pointing to the teacups. "Flummery, all got up for the express purpose of hoaxing us, somehow. What price secret society now? I know; you thought Keating gave a password. But you can't tell me there was a meeting here, and that ten members vanished out of here instead of one murderer. Ah, well. Cheer up; don't look so glum. We were had for a prize parcel of mugs, right enough, but I don't see what else we could have done or had a right to do. Besides, the old man should be here before long. He'll arrive mad as fifty hornets, but I don't mind telling you I'll be pleased to show him the one closed circle he won't be able to get out of." Masters studied the body. "This chap Keating, Bob. Know anything about him?"

"Nothing beyond what I told you this afternoon, after he'd bought the house and tossed us out---'

"Yes. He was fair set on dying, wasn't he?" asked Masters quietly.

Pollard looked at the limp body in gray flannel, its spine broken and its straw-colored hair blackened into the brain.

"He's got a lot of money," the sergeant said. "And he likes to call himself `the last of the Venturers.' That's why I thought he'd be interested in any secret society, if it were sufficiently mysterious or sufficiently lurid. What he wanted, he said, was thrill. I believe he lives in a flat in Westminster; Great George Street, I think."

Masters looked up sharply. "Great George Street, eh? So that's where he went!"

"Where he went?"

"Yes. Today. You haven't forgotten he left here this afternoon at ten minutes past two o'clock, and didn't return until a quarter past four? Just so. I know where he went," Masters announced, with satisfaction, "because I tailed him myself. But that's neither here nor there, at the moment. What about his relatives, or friends? Know anything about them?"

"No-no, I'm afraid not. I know he's got a cousin named Philip Keating. And he's engaged to be married to Frances Gale. You've probably heard of her; she's the one who seems to have been winning all the golf tournaments."

"Ah? I've seen her picture in the papers," said Masters, with interest. He ruminated, evidently turning the picture over in his mind. "She wouldn't be mixed up in games like this, I'll bet you a tanner," he decided. "Never mind. Here: lend a hand, and let's turn the poor chap over on his back. Easy now. . ."

"God!" said Pollard involuntarily.

"So he wanted thrill," observed Masters after a pause, during which there was no sound but Masters's asthmatic breathing. "Not pretty, is it?"

They had both risen. No damage had been done to the face which was now exposed, except a spiritual damage. But mind, as well as life, had gone out of it; and the reason for its witless look was fear. Pollard had read much of faces supposed to be distorted with the fear of something seen. During his term as a uniformed constable he had seen a man fall to death out of a high window, and a man get the charge of a shotgun full in the face. The feelings such sights inspired were of physical things like pulp and angles; yet they were of the same cold quality as those inspired by this undamaged face, whose pale blue eyes were wide open and whose straw-colored hair was neatly plastered down. Quite plainly, he did not care to look at it. Keating, who wanted thrill, had evidently seen something more horrible than that which comes into the homes of harmless men.

"I say, my lad," put in Masters gruffly. "How would you like to spend a night in this room?"

"No, thanks."

"Just so. And yet what's wrong with the place? It's ordinary enough, you'd say. I'd rather like to know who was the last tenant." After a somewhat sharp glance round the room, Masters squatted down by the body and began to turn out the pockets. "Stop a bit! Here's something. What do you make of this, for instance?"

"This" was a thin and polished silver cigarette-case. It was not in Keating's pocket; it had evidently been lying under the body, partly inside the fold of the coat. Masters snapped it open, finding that it was filled to capacity with Craven A cigarettes; but Masters handled it very gingerly, by each end only, for on the polished surface there were several clear fingerprints.

"It's got a monogram in the corner," said Pollard. "Do you make out the letters? J.D. That's it: J.D. It isn't Keating's. It may be what you're looking for."

"If the old man were here," said Masters, with a heavily ruminative air, "he'd say you'd got a simple straightforward mind, my lad. This murderer is much too canny a bloke to smear up the best fingerprint-surface in this room. We'll see; but I'll make you a little bet that these prints are Keating's, and that he's been carrying somebody else's cigarette-case." He folded up the case carefully in a handkerchief. "Point is, what's the thing doing under his body? He didn't smoke at any time-nobody did; just like the Dartley case. At least, there aren't any cigarette-ends in the place, and the case is full. If he was carrying somebody else's case ... here, that reminds me! Whose hat was he wearing? I shouldn't think it was his own. And where's the hat now, by the way?"

Pollard crossed the room to the divan, which was pushed out a little way from the wall, and felt down behind it. He fished up a gray Homburg somewhat crumpled. It had been lying on the divan, he remembered, when he had made his first search of the shrine. He turned it over, handing it to Masters and pointing to the band inside; on the band was printed in gilt letters the name Philip Keating.

"'Philip Keating,"' repeated Masters. "Oh, ah? That's the cousin you mentioned, is it? Yes. It's a good thing for Mr. Philip Keating we all know his cousin was wearing the hat, or he might find himself with a lot of questions to answer. This is a very casual sort of young gentleman, Bob. He wears somebody else's hat, and he carries somebody else's cigarette-case we think. Ur! I know that type. Can you tell me anything about this Mr. Philip Keating?"

"Well, sir, he'd probably sail up to the ceiling and bust if he were ever involved in a murder case. He's a stockbroker, I think; very pleasant, but respectable as the devil."

Masters looked suspicious. "All right. We'll go into that.

But is there anybody connected with either of 'em whose initials are J.D.?'

"I can't tell you that."

"Let's see what's on him, then. Put all that stuff out in a line. Now, then: wallet. Eight pound ten in notes, and a couple of his own visiting-cards. (Yes, that's the address: number 7 Great George Street.) Nothing else in the wallet. Fountain-pen. Watch. Bunch of keys. Box of matches. Handkerchief. Six and four-pence in coppers. That's the lot, and not much to go on. Except that he was a heavy smoker: every pocket's got tobacco in the lining."

"Unless he's wearing somebody else's suit," said Pollard. "He was a heavy smoker, but he didn't light up during a three-quarters-of-an-hour wait. Look here, sir, do you think it was to be some sort of-religious service?"

Masters grunted noncommittally. "No, the tailor's label's all right. It's his own suit. You think you're making jokes, my lad, which aren't funny. But I don't. I go at it. I've seen queerer things ... ah, Inspector! Come in."

Divisional Detective-Inspector Cotteril was a long lean man with a long melancholy countenance, which he balanced by an affable manner. But he saw the upturned face of Vance Keating, and whistled.

"Cor! There's a sight for you," he said. "The house has been searched, every inch of it. I can tell you now that there isn't, there wasn't, there hasn't been anybody else in it; but you knew that already. We're at a dead end. But here's what I wanted to ask you, Chief Inspector. Do you want our division to go on with this, or will the Yard take over? The Yard, I suppose?"

"I suppose so. But that'll be decided this afternoon. You can carry on with finding out what hauling company brought this furniture here two days ago, where they got the furniture, and trace it back as far as it'll go. I think we'd better take charge of this revolver: it's a curio, and there's no registration number. But I'd like to get some information. Do you know anything about the last tenants of this house?"

Cotteril reflected. "Yes, I can tell you myself. I remember, because the people came round to the station once to report a golden cocker spaniel being stolen; and I own one myself. Now, what in blazes was that name?" demanded Cotteril, and knocked at his temple. "Mr. and Mrs… . But I don't think you'll find much there. As I remember him, the old man was a solid solicitor; you know, old and crusted; elderly.

Had a very pretty wife. Damn it, what was that name? I can remember everything except that. They moved out of here about a year ago. The name was something fancy; I think it began. with a D. Mr. and Mrs.- I know: got it! Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy Derwent!"

Masters stared at him, his color changing a little. "You're sure of that, now?"

"Pretty sure, yes. Certain. The dog's name was Pete." "Man, listen! Don't it mean anything to you? Don't you remember the Dartley case?"

Cotteril opened one eye, and spoke drily. "Not personally, thank the Lord. I was shifted here from C Division just after all the rumpus. I know about it, of course. I know how it's repeated here."

"Dartley got it through the back of the head at 18 Pendragon Gardens. The last tenants of 18 Pendragon Gardens moved out less than a week before the murder. They were Mr. and Mrs. Jeremy Derwent. They were so plain downright respectable, it was so clear they'd got nothing to do with Dartley, that we never bothered much with them. But now they turn up as the last tenants of 4 Berwick Terrace. And under Keating's body is that cigarette-case marked with the initials J.D." Masters pulled himself together. "Just so. I'm a bit curious to know what Sir Henry Merrivale will make of that, my lad."

CHAPTER FIVE

Dead Man's Eyes