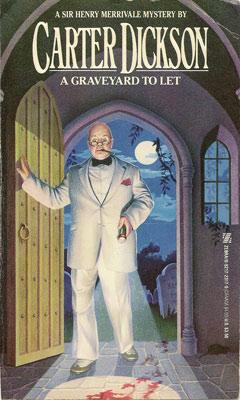

Carter Dickson

(John Dickson Carr)

A Sir Henry Merrivale Mystery

A Graveyard to Let

MURDER MOST FOUL

The young man he saw running—slowly now, with panting breath—was one whose name or face Cy did not know. But he was one of the outfielders who had been sent to get a lost ball. He was now gasping out words like, "flashlight," and "doctor." He stumbled up to them, his eyes scared under the peaked cap.

"What is it, son?" H.M.'s big voice demanded.

"Out in that graveyard," the young man said between breaths, "the graveyard they don't use any more... on one of the tombstones..."

"Well?"

"Bill and I," the young man said, "found someone's body."

ZEBRA BOOKS KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

ZEBRA BOOKS are published by

Kensington Publishing Corp. 475 Park Avenue South New York, NY 10016

Copyright © 1949 by William Morrow & Co., Inc. Copyright renewed 1977 by John Dickson Canr.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

First printing: March, 1988

1

Not without reason did the late and great O. Henry refer to New York as Bagdad-on-the-Subway. Any kind of Arabian Nights' adventure can occur there, and very often does.

Indeed, considering the regrettable behaviour of Sir Henry Merrivale in that same subway...

But let us first indicate the paths of several lives which were converging, towards a point of irony, on that very hot afternoon of Monday, July 6th. Sir Henry Merrivale, himself, wearing a tweed cap and a suit of plus fours which would have inspired aesthetic agony even without his corporation or his countenance, arrived on the Mauretania.

The thermometer stood at ninety-eight. The skyline of lower Manhattan loomed in hard sparkle against a sky like milk on the boil. By the time the liner discharged her passengers, at half-past two in the afternoon, Sir Henry Merrivale had been almost too well photographed and interviewed. He held forth on the international situation with such fluency and lack of discretion that even ships' news reporters felt a qualm.

"Look, sir," interposed one of them. "You'll back this up, will you? If s not off the record?"

"Oh, my son!" said H.M., waving his hand in a disgruntled way. "I called a so-and-so a so-and-so, and he is. That's simple enough, ain't it?"

"Listen!" begged a photographer, who had been dodging back and forth behind his camera like a sniper in ambush. "You say you like this country, don't you?"

H.M. directed towards this man, through his big spectacles, a scowl of such horrible and terrifying malignancy that any such photograph ought to have borne the caption, "$5000 Reward." H.M. also removed his cap, so that the sun could heliograph more evil from his big bald head. The photographer pleaded again.

"Look! I want you to express pleasure!"

"I am expressin' pleasure, dammit!"

"What are your plans, Sir Henry?"

"Well... now," said the great man, "I got to visit a family in Washington."

"But aren't you staying any time in New York?"

"Y' know, I'd like to." Across H.M.'s unmentionable face crept an expression which Chief Inspector Masters, had he been there, would have recognized for wistfulness mixed with pure devilment "I'd like to visit a friend or two of mine. Or go out to the Polo Grounds, maybe."

"Polo Grounds?" yelped another voice. "But you're an Englishman, aren't you?"

‘Uh-huh."

"Do you know anything about baseball?"

H.M.'s mouth fell open, a wide cavern. It was as though you had asked the late Andrew Carnegie whether he ever heard of a free library.

"Do I know anything about baseball?" powerfully echoed H.M. "Do I know anything about baseball?" Hitching up his trousers, he opened and shut both hands to beckon his companions closer. "Looky here!" he said.

At about the same time the great man was being interviewed, one of the friends of whom he had spoken was no great distance away as the crow flies. Mr. Frederick Manning, of the Frederick Manning Foundation, entered the head office of the Token Bank and Trust Company, and went down to the safety-deposit vault

From there Mr. Manning emerged some twenty minutes later, with his brief case looking a good deal thicker than before. In lower Broadway the sun carved a glittering cleft, winking back at him from green and yellow taxies. Under the Corinthian pillars of the bank, Mr. Manning stood for a moment and swore mildly.

He did not like heat He was one of those men who merely turn lobster pink and peel. Frederick Manning, at fifty-one, was spare and lean, a little over middle height with silver grey hair and a pair of vivid blue eyes whose expression he tried to veil rather than to use. His reputation was that of a good businessman, although business he left to his lawyer. Frederick Manning was more man-of-the-world than businessman, and more scholar than either.

"Oh, well!" he said quietly. After this he apostrophized lower Broadway with a quotation from Milton which startled several passers-by. Then, unruffled, he hailed a taxi.

He was driven uptown to his club, where he had lunch alone. In connection with the whirl of ugly events which were to follow, it maybe mentioned that Mr. Gilbert Byles, the District Attorney of New York County, was a fellow member of the club. Mr. Byles, whom the press described as "our beat-dressed D. A.," several times glanced towards Manning across the dining room.

But Manning, evidently so preoccupied that he did not even notice an old acquaintance, hardly touched his food and never glanced up. He was doing sums in arithmetic on the back of an empty envelope. Finally, and with hesitation, he twice wrote the words "Los Angeles."

"Coffee, sir?" inquired the waiter.

"Not good enough!" muttered Manning, and scratched out the words.

"Then can I get you something else, sir?"

"Eh?" said Manning, and clearly wrote "Miami."

"If you don't want coffee..."

Frederick Manning woke up. The blue eyes, against lean pink face and silver grey hair, returned to the vividness of a strong and towering personality. He crumpled up the envelope and threw it aside.

"I beg your pardon," he said, with that engaging smile which had charmed so many. "Coffee, of course."

Shortly afterwards, under the hammering heat, he walked across to the Lubar Building at the corner of Fifty-first Street and Madison Avenue.

His suite of offices, on the twenty-second floor, had only one entrance. Its glass panel bore in small chaste gilt letters, The Frederick Manning Foundation. It brought to mind the Frederick Manning School at Albany, a school philanthropic and non-profit-making, which tried to teach the creative arts. Manning, they said, had only two passions in life, and one of them was this school. At the moment the air conditioning of the building soothed him, calmed him, quietened the emotion which few of his friends ever saw.

And yet trouble exploded as soon as he opened the door.

"Mr. Manning!" softly called the woman at the reception desk. She herself was middle-aged and looked rather like a schoolmistress.

"Yes, Miss Vincent?"

Miss Vincent was perturbed, which no receptionist should ever be. Yet her eyes rather than speech or gesture summoned him to the desk, where he punctiliously removed his loose-fitting Panama hat.

"I thought I'd better tell you," Miss Vincent added in a low voice, "that your daughter is waiting in your office."

"Which daughter?"

"Miss Jean, sir." There was a barely perceptible pause. "And Mr. Davis is with her." Manning, who had been leaning forward with both hands on the desk, straightened up. Miss Vincent felt rather than saw the blaze of anger which surrounded him as she said, "Mr. Davis," and she could guess why. But his eyes remained opaque, his voice steady.

"Is my secretary in?" he asked.

"Yes, Mr. Manning."

"Very well. Thank you."

At his left was a narrow soft-carpeted corridor -which ran past small offices like boxes with frosted-glass sides. It was all very cool, very modern, an incongruous background for Manning, who at the moment could have been called neither. At the end of the corridor was the door to his private office.

Manning, with a mouth of contempt, glanced down at the floor. Evidently to help the air conditioning, a marble bust of Robert Browning—the only ornament of its kind in Manning's office—had been used as a doorstop to keep the door part way open.

Manning, like one whose rage is shown only by murderous care, stepped softly over the bust as he opened the door, and closed the door on it with the same murderous care.

"Hello, Dad!" exclaimed the voice of his younger daughter—brightly and rather shakily.

"Good afternoon, sir," said the voice of Mr. Huntington Davis, Junior.

It was not Manning's arrival which caused tension there. Tension already existed. But it grew stronger each second afterwards.

Manning's office, large and square, was at a corner of the building; there were two windows in the wall on either side of him. But the Venetian blinds had their shutters more than half closed, turning the room dim. Its sombre grey furnishings, including a heavy sofa, were as uncompromising as the muffled carpet or the framed photographs of the Frederick Manning School and its achievements.

And still the silence lengthened, while Manning hung up his hat and sat down unhurriedly behind the big flat-topped desk in the angle of the window walls.

"Dad!" Jean Manning burst out uncontrollably.

"Yes, my dear?"

"I want to ask you a question," said the girl, "and you've got to answer me! Please!"

"Of course, my dear," assented her father. Not once did he glance in the direction of young Mr. Huntington Davis.

"Well..."

Jean braced herself.

She was just twenty-one, and badly upset. Wearing a white silk dress, she sat on the sofa with one leg tucked under her. Though Jean was very pretty, with her yellow hair worn in a long page-boy, she had not the stereotyped prettiness which makes so many girls nowadays look exactly alike: as though they had all stepped simultaneously from the same fashion magazine, and started to parade down Fifth Avenue.

Jean wore very little make-up, perhaps because of her very faint but healthy tan. Her blue eyes were direct and honest, if a trifle naive. When she flung out the question that had been torturing her, an older person might have found it something of an anticlimax.

"Is it true," she demanded, "that you've been running around with this dreadful woman? Just as they say you have?"

For a moment Frederick Manning did not reply.

A detached observer would have said this question, and this question alone, really startled him. For a moment there was a faint twinkle in his eye; then his jaw muscles tightened, and his nostrils distended.

"Aside," he said, "from the term 'running around,' which I hate, and the word 'dreadful, which is inaccurate..

"Oh, stop it!" pleaded Jean, and struck the arm of the sofa.

"Stop what?"

"You know what I mean!" Jean turned back again to the question of the woman. It was as though a spider had run up her bare arm "Are you—are you keeping her?"

"Certainly. I believe that's the correct procedure. It doesn't shock you, does it?"

"No, of course not!" Jean said instantly. She would have been outraged at the suggestion that anything could shock her, though in fact many things did. "It's just—I'm sorry, Dad!—that it seems indecent. For a man as old as you are!"

"Do you honestly think that, my dear?" smiled Manning.

"And that's not all. There's—well, there's mother."

For a moment Manning tapped his fingers on the desk.

"Your mother," he replied, "has been dead for eighteen years. Do you remember her at all?" "No, I don't! But..."

Jean, thoroughly miserable and almost in tears, lost in a romantic dream, did not notice that her father's face was almost as white as her own.

"But," Jean went on doggedly, "you've always told us how you idolized her. How you worshipped her. How you felt,"—Jean's eyes strayed towards the marble bust which served as a doorstop— "how you felt about her like Robert Browning felt about Elizabeth Barrett, even after she was dead?"

Manning closed his eyes..

"Jean," he said, "will you oblige me by not saying 'like' when you mean 'as?' Of all the detestable..."

"Dad! I don't understand you!" Jean cried helplessly. "What difference does it make how I say it?"

And now Manning's face flamed.

"Your speech, my dear, is the speech of Emerson and Lincoln, of Poe and Hawthorne." Manning spoke gently. "Don't debase it."

"Oh, Dad, you're a hundred years behind the times!"

"And yet far too modern, apparently, when I take up relations with Miss Stanley?"

"That woman..." Jean began vehemently. Then she stopped, attempting without great success to imitate the cynical and world-weary air of her twenty-four-year, elder sister, Crystal.

"Oh, I imagine people in the old days had their floozies too." Then her tone changed. "But you! And I still say, Dad, you're a hundred years behind the times! That's probably why your school..."

Again Jean paused, but this time with a different inflection.

"What about the school?" demanded Manning, with the blue veins showing at his temples.

He had seen his daughter's gaze stray towards the black brief case, obviously well filled, which lay on the desk at his right hand. Without haste Manning picked up the brief case, and, as though idly, shut it up in a drawer at the right of his desk.

"What about the school?" he repeated.

Jean looked round for help. "Dave!" she cried.

Mr. Huntington Davis, Junior, cleared his throat and got up from an easy chair at the far end of the room.

The office was so dark, with its sunblinds nearly drawn, that faces looked vague at a distance. Mr. Huntington Davis—the newest partner of his father's old-established brokerage firm of Davis, Wilmot & Davis—had more than the assurance of his thirty years. His black glossy hair, parted to a nicety, gleamed against the sunblinds as he strolled over to Manning's desk.

"May I say a word, sir?" Davis requested easily.

"By all means," agreed Manning. He looked the young man up and down without expression, as he might have looked at a canvas without any painting on it.

Davis smiled his pleasant, white, dental smile. He was of good height, a joy to his tailor, and with a passion for physical exercise which Manning (to say the least) deplored. Under Davis's black hair he was tanned to the colour of an Indian, his pale grey eyes showing light against it.

Negligently he leaned one fist on the desk.

"I'd like to ask you something, Mr. Manning," he said. "What are you really thinking about?"

"I was wondering," mused the other, putting his fingertips together, "why you and I dislike each other so much."

"Dad!" cried Jean.

Davis smiled, a white flash against the tan of the face.

"That's not true, Mr. Manning." he said earnestly. "I certainly don't dislike you. And you can't actually dislike me either."

"What makes you think so?"

Without taking his eyes from the lounging figure behind the desk, Davis extended his hand behind him and beckoned to Jean. Jean slipped off the sofa and hurried to take his hand, pressing it.

"Well!" smiled Davis, with humour wrinkling his forehead. "You don't object to my marrying' Jean, do you? You gave your consent without a murmur."

"I almost always consent," observed Manning, "to avoid fuss and bother. Jean's sister has been married three times."

"Look, sir!" said Davis. There was a note almost of desperation in his self-assured voice. "Jean and I are getting married in August. This is a family matter now. I want to help you! Look, don't you trust me?"

"Not one millionth of an inch."

"But why? Why do you dislike me so much?"

"I don't know, Mr. Davis. Call it instinct."

Davis made a slight gesture which sent Jean back to the sofa.

Then Davis, settling the shoulders of his well-tailored blue suit, drew himself up. He smiled. He was Young America Succeeding in Business.

"I'm afraid, Mr. Manning," he said in a stern yet kindly voice, as though addressing a child, "you don't appreciate what a bad position you're in. And I'd better tell you: you may get into serious trouble. What do you say to that?"

Manning raised his eyes briefly.

"Only, young man, that your effrontery would stagger an Egyptian mummy."

Davis lifted his shoulders carelessly.

"Have it your own way, then," he smiled. "But of course... you haven't heard the rumours that are going around."

"What rumours?"

Davis chose to ignore this.

"Mind you," he warned darkly, "I didn't have to tell you this. Maybe I can't help you, even as it is; probably not But I did want you to know I was a friend of yours, no matter how bad a jam you might get into."

"What rumours?" Now was the moment

"Well, sir, I'd better be frank with you. They say this Frederick Manning Foundation of yours"— Davis glanced round the room—"is in pretty bad shape financially. And that there's going to be a crash. And that you're in it up to your neck."

There was a silence. Manning slowly rose to his feet behind the desk. A stray gleam from the sunblinds caught his silver grey hair.

"You impertinent young swine,"he said.

Though Manning did no speak loudly, the last word had the thud of a thrown knife. In that moment he seemed to tower over Davis, to extinguish Davis into trumpery tailoring and paling suntan.

"It isn't true, is it?" cried Jean. "It isn't true, Dad? About the—business troubles?"

"Certainly not," Manning replied with dignity. Then he turned to Davis. "Get out!" he shouted. Get...

And then there passed over Manning's face one of those instantaneous changes which, to anyone who did not know his heart and his curious sense of humour, would have been inexplicable at the time. The look he directed at Davis was almost cordial. His bass voice sank to purring smoothness.

"Tell me, Mr. Davis," he pursued, "have you any engagement for tonight?"

Davis, by this time thunderstruck, could only stare back at him.

"If you haven't," said Manning, "could you come out to Maralarch and join us for dinner?"

"You couldn't keep me away," Davis said curtly.

"This morning I told Jean, as well as my daughter Crystal and my son Bob, that I had something very important to tell them at dinner tonight" Manning looked at Davis. "My lawyer will be there; and you will make a sixth. I also hope to have a rather distinguished seventh guest."

"Seventh guest?" repeated Davis. He was watching Manning as warily as Manning watched him. "Mind telling us who it is?"

"An old friend of mine from England. His name is Merrivale, Sir Henry Merrivale."

Jean, who was now standing in the middle of the room, made a gesture of dispair.

"Yes," she said in that same despairing tone. "And that's all we need now, isn't it?"

Her father frowned. "I don't quite follow you, Jean."

Jean's blue eyes looked at him steadily.

"You're going to tell up something horrible tonight, aren't you? Please don't deny it! I know you are! Dad, what are you going to tell us?"

Manning hesitated, an impressive figure even in his loose white alpaca suit.

"That can wait." He hesitated again. "But if you were shocked at anything I said this afternoon, Jean, you will be far more shocked tonight."

"Sir Henry Merrivale!" wailed Jean.

"Really, my dear, I still don't understand why..."

"Crystal," explained Jean, "is positively in raptures. She looked him up in Debrett. He's got a lineage as long as your arm, and a string of degrees after his name too. On top of everything, don't we just need an English baronet who’ll be so frozen and refined that we'll all be scared to talk to him?"

"Ah, I see," her father murmured. Then he glanced at his wrist watch, and got a real start. "Good God, that liner was supposed to dock at two-thirty! And it's three-thirty now! Just one moment."

Sitting down behind the desk again, Manning clicked the switch of the talk-back connected with his secretary's office in the next room.

"Miss Engels!"

The voice which answered sounded rather flustered. "Yes, Mr. Manning?"

"Miss Engels, you did send off that radiogram to the Mauretania early this morning?" "Yes, Mr. Manning."

"I sent Parker down there to meet the ship, and drag old H.M. here if he had to kidnap him. What's the matter? Isn't the ship in?"

"Yes, Mr. Manning. The ship's in. Mr. Parker - well, he called up about five minutes ago. But I—I didn't want to disturb you. As for Sir Henry, Mr. Parker couldn't get near him."

"What do you mean, couldn't get near him?"

"Well, it seems Sir Henry left the ship with a lot of reporters. They climbed into cabs and went over and started a poker game in the back room of a bar on Eighth Avenue. The bartender wouldn't let Mr. Parker in."

"A poker game?" echoed Jean Manning.

Whatever she may have said before, Jean's sympathies were quickly roused. She was passionately loyal to a friend, or even the friend of a friend.

"That poor, innocent Englishman!" she cried. "They trapped him into it! They won't leave him a cent to his name!"

"Be quiet, Jean!—Yes, Miss Engels?"

The talk-back switch kept on clicking, not always accurately.

"Mr. Parker waited in a drugstore, sir. In about three quarters of an hour," answered Miss Engels, "Sir Henry came out of the bar stuffing wads of money in his pockets. He said he had to go to Washington. He jumped into a cab and yelled, 'Grand Central Station.'"

Huntington Davis, who had regained all his self-assurance, intervened here.

"But he can't get to Washington from Grand Central! He's got to go to Penn Station! Didn't they tell him that?"

"Goon, Miss Engels!"

The secretary's voice grew apologetic.

"Mr. Parker says he's sorry, sir, but he can't go on with a chase like that While he was in the drugstore, Mr. Parker phoned a friend of his"— here Miss Engels obviously consulted notes—"a Mr. Cy Norton."

"Good!" beamed Manning. "Excellent!"

"Who's Cy Norton?" asked Jean.

"For eighteen years," retorted her father, "Cy Norton was London correspondent of the Echo. He knows Sir Henry far better than I do. I hadn't even heard he was back in New York." Manning turned to the talk-back. "Has Mr. Norton picked up the trail already?"

"Yes, sir. Hell phone you as soon as there's news."

"Thank you, Miss Engels. That's all."

Manning, in a kind of anticipatory fever, rubbed his hands together.

"But Grand Central..." Davis burst out.

"I have no doubt," Manning observed calmly, "that Sir Henry knew he was going to the wrong station."

"Is he crazy, sir?"

"Far from it. The best term to describe him is the good old American word ornery. He is ornery."

"But..."

"He must not get to Washington," Manning said fiercely. "He must be at Maralarch tonight and especially tomorrow morning. I swear it! But I wonder what he's doing now?"

2

Voices of many loud-speakers, hollow yet rasping, spoke their ghost message through the vastness of Grand Central Station.

"Sir Henry Merrivale." Slight pause. "Sir Henry Merrivale.''Slight pause. "Please come to the station-master's office on the upper level near track thirty-six.''

And still the old man didn't show up.

Cy Norton, smoking a cigarette near the information desk, kept swivelling round and round with his eyes on a comparatively small crowd.

Eighteen years ago, when he was first sent to London as correspondent for the Echo, he had not been impressed—as few sensible people are—by St Paul's Cathedral. He had written that St. Paul's looked exactly like Grand Central Station with an acre of folding seats.

Now, as he stood in the main hall on the upper level, amid a marbly shuffle-shuffle of feet, the old memory returned. So many memories, both ugly and pleasant! And always, of course, the face of a certain girl...

"Sir Henry Merrivale! Sir Henry Merrivale! Please come to the Station-master's office on the upper level near track thirty-six."

Again it echoed and died under the mutter of the crowd.

Standing there in an old grey flannel suit he had bought before the war, his dark blue tie hanging out over the double-breasted jacket, Cy Norton might have been a difficult man to plaice. He was very good-natured, and looked it. He had a lean sardonic face, with fair hair as thick as it had ever been. He was over forty, and showed it.

Yet, despite the battering of time and war, Cy retained an enormous and youthful zest He had not even sworn very much, a few weeks ago, when they politely booted him out of his job.

"We fear," they had cabled from New York, "that he is losing his American point of view."

And who the hell, reflected Cy Norton, wouldn't tend to lose his "American point of view" in all those years? Was it possible—Cy tried not to fool himself—that he could see things from too many sides, from too many countries? Or that he was at last writing real journalism, instead of his earlier antics? Or, most of all, that...

"Mister!" cried a hoarse voice, accompanied by the noise of running and dodging feet. "Mister!"

A grimy-faced boy of twelve or so, whose aid Cy had enlisted with money and with the flattering promise that he should play Dick Tracy, cannoned straight into him.

"He ain't there," the boy confided, breathless yet with a conspiratorial look round him. "They've paged him five times, and they won't do it no more. But he ain't there!"

Cy Norton's heart sank.

"That's bad," he said. "I thought he'd be certain to go there. I was counting on it'"

"Howdja mean?"

"He couldn't resist that loud-speaker! If he heard it, he'd want to go and use it himself and talk to the whole station."

"Cripes!" said the boy. His eyes opened to white disks at the majesty of this conception. "What madeja think of that?"

"Because," admitted Cy, "it's exactly what I've often wanted to do myself, only I haven't the nerve. I mean, they wouldn't really let him recite the limerick about the young girl from Madras. But he'd try."

"Mister, we gotta find him!"

Cy's feverish eyes sought the illuminated clock over the information desk. It was twenty-five minutes to four.

"If he didn't hear the loud-speaker," Cy decided, "either he's left the station or else he's in one of the shops in all these arcades. Probably a bookshop."

"There's lots of bookstores in this place," yelled the boy. "Come on!"

Beckoning, he raced off in the direction of the Vanderbilt Avenue side. Cy Norton, remembering with pleasure that he had not put on a pound of weight in fifteen years, plunged after him.

Lighted arcades loomed up and were explored, amid a rainbow profusion of goods which would have dazed a Londoner and still dazed Cy. Their footsteps clattered and echoed on marble until the boy, doing a graceful skid-turn at a last arcade, pointed ahead.

Well down on the left was another chaste Doubleday bookshop. They did not find H.M. there. But Cy, as he glanced at the line of glass doors to the subway which cut off the end of the corridor, and seeing who was beyond those doors, uttered a grunt of triumph.

"Here," he said, pressing another dollar bill into the boy's hand. "That's all, Dick. We've done it!"

And he hurried through one of the glass doors.

The warm, stale, oily breath of the subway blew round him. On his right, eight turnstiles—with new metal separations, painted dull green, since the fare had been increased to ten cents—faced an iron-shod staircase leading down to the shuttle service between Grand Central and Times Square.

On his left, against a white-tile wall, was a big money-changing booth with a grill over its aperture. In the open space between turnstiles and money-changing booth, but well back beyond both of them, stood a very large and very old Gladstone bag stained with ancient travel labels. On the travelling bag, with his arms folded like Napoleon departing for St Helena, sat Sir Henry Merrivale.

Facing him, fists on hips, stood a policeman. Now there are those who maintain that if Cy Norton had intervened then and there, before anything had happened, all yet would have been well. But to these Cy has a firm reply.

"The cop," he will point out, "wasn't on duty. He was a motorcycle cop, black leather leggings and all. Finally, he was in a good humour."

And so he was, when he first faced H.M.

"What’s the matter, Pop?" the policeman called jovially. "Haven't you got any money for your subway fare?"

H.M., bald head lowered and corporation outthrust, gave him a malignant look over the big spectacles.

"Sure I got money," he retorted, suddenly digging into his pocket and holding out a handful of change. On the tip of one finger was balanced a dime, on the tip of another a nickel.

"But for fifty years, burn me," added H.M., looking first at the dime and then at the nickel, "I've never understood why the little one is worth more than the big one."

"What's that?"

"Never you mind, son. I was just cogitatin'."

The policeman, who was young and a fine figure of a man in his uniform, strolled over and studied him.

"Say, Pop, who are you?"

"I'm the old man," said H.M., dropping the money back in his pocket and tapping himself impressively on the chest. "And I'm mad, too. I'm good and mad."

"No, but I mean: aren't you sort of English?"

"What d'ye mean, 'sort of English? I smackin' well am English!"

"But you talk like an American," objected the policeman, as though pursuing an elusive memory. "Wait a minute; I know! You talk like Winston Churchill. And he talks like an American. I've heard him on the radio. 'Course, in most ways," the policeman added carelessly, "he is an American."

H.M.'s face turned a rich, ripe purple.

"But look, Pop," the policeman continued in a persuasive tone, "why are you sitting here on your bags? And what are you so mad about, anyway?"

With a violent effort H.M. restrained himself. His voice, which at first seemed to come in a hoarse rumble from deep in the cellar, steadied itself. But he could not prevent himself from swelling up with a terrifying effect.

"I want to make a statement, son," he said.

"O.K.; make a statement!"

"I wish to state," said H.M., "that this subway, which you ought to call an Underground—that this subway, of all the subways in which I have ever travelled, is unquestionably the goddamnedest subway."

The policeman, though genuinely good-natured, was stung to the quick. Born in the Bronx and christened Aloysius John O'Casey, he felt his own temper rising.

"What’s the matter with this subway?" he demanded.

"Oh, my son!" groaned H.M., with a dismal wave of his hand. "I'm asking you, Pop: what's the matter with this subway?"

To Cy Norton, standing near the glass doors with his hat hiding his face to keep it straight, the policeman's question seemed justified. The rush hour had not yet come. Only a few persons hurried across, to a clank of turnstiles, and clattered downstairs. Near the money-changing booth lay a coil of rope left behind by workmen. Lights, red and white, winked in the cavern below; another train rumbled out

"I'm asking you, Pop: what's the matter with this subway?"

"I come in here," said H.M. "I put a dime in the slot beside that turnstile. I get into a train, as good as gold."

"All right so what?"

"The first station I get to," said H.M., "is called Times Square. Fine! I look out the window at the next station, and it says Grand Central. 'Lord love a duck,' thinks I, 'it must be confusin' as hell to have two stations with the same name.' The train goes hopperin' on, and burn my heavenly britches! if it ain't Times Square again. The next station is Grand Central."

Officer O'Casey spoke gently.

"Look, Pop. This is the shuttle! It only goes between here and Times Square!"

"That's what I mean," said H.M.

"Howdja mean-whatcha mean?"

"What in Esau's name is the good of a subway that only goes to one station?"

"But you can change for any place from there! It's a service, see? It's..." Officer O'Casey, swallowing hard, was seized with inspiration. "Listen, Pop," he pleaded. "Where do you want to go?"

"Washington, D.C."

"But you can't go to Washington by subway!"

H.M. extended his hand, palm upwards, in a lordly and insulting. gesture towards Officer O'Casey's subway.

"See what I mean?" he inquired.

"You're drunk. I ought to run you in," said the policeman, after a deadly pause.

"You see those turnstiles?" said H.M., leering up at him.

"I see 'em, all right! What about 'em?"

"I've just magicked ‘em," said H.M. "I put the old voodoo spell on 'em." Then he advanced his unmentionable face. "What d'ye want to bet I can't walk through any of the turnstiles and never drop a dime in the slot?"

"Now look here, Pop!..."

"Ho!" said H.M. "You think I'm kiddin', hey?"

He rose to his feet, the tweed plus fours adding more of a barrel shape. Majestically preceded by his corporation, he approached the nearest turnstile. Then, gracefully holding both arms in the air like a ballet dancer, he just as gracefully maneuvered his corporation against the turnstile. It clanked, and he went through.

"You come back here!" yelled Officer O'Casey.

"Sure," said H.M., instantly returning through the turnstile and just as instantly going back through another one—still without benefit of any fare.

"Voodoo," he explained with a modest cough.

For a moment the policeman stared at him. Then Officer O'Casey charged at that turnstile like a bull at a gate. But it held him.

"Y'see, son?" H.M. inquired pityingly. "You can't do it unless you know the voodoo words. And I expect," he pointed, "that feller in the money-changing box is just about having high blood pressure, ain't he?"

It was true, as Officer O'Casey’s glance confirmed. The young man who gave change was gibbering behind the bars.

"What the hell's going on out there?" he screamed.

The great man was paying no attention.

"I keep telling you," he rumbled patiently, "that they're all magicked. You can't get through without payin' unless you know the voodoo words."

Officer O'Casey's colour changed again. The .38 police-positive revolver shook in its holster against his hip. But his flaming curiosity was stronger than his instinct for law and order.

"Listen, Pop," he said in a low voice. "I’ll bite. I know it's a gag. But what are these voodoo words?"

"'Hocus pocus,'" H.M. said instantly. "'Allagazam. Cold iron and Robin Goodfellow.' That's all."

"But I can't say that!" "Why not?"

"I don't know," admitted the policeman, with a red colour coming up his face from under the uniform collar, "But it sounds crazy. It sounds..."

Then his whole tone changed.

"'Hocus pocus!'" said the policeman, extending his finger at the turnstile."'Allagazam! Cold iron and Robin Hood!'" He charged at the turnstile, and went through so easily that he nearly pitched headlong down the stairs.

But neither Officer O'Casey nor Sir Henry Merrivale had anticipated what happened next

A thunderous wave of applause, hand-clapping rising above the cheers, swept through that sour cavern and echoed back from its walls. Officer O'Casey had forgotten the crowd which can assemble in an instant, as though "magicked," at the least sign of monkey business. They poured down through the arcade from Grand Central, and through the two other entrances to the shuttle.

Office O'Casey was as red as a beet But H.M., whose worst enemy could not have called him bashful, assumed a dignity like Napoleon at Austerlitz and bowed as low as his corporation would permit He also raced in and out of two more turnstiles before the policeman collared him.

"Keep back!" shouted Officer O'Casey to the crowd. "I'm warning you now: keep back!"

Officer O'Casey was wearing a gun. They kept back.

"Jake!" he yelled to the consumptive-looking youth who kept the change booth. Jake hurried out being careful to lock the door behind him.

"Now look, Jake! There's something wrong with these turnstiles!"

"I tell you," Jake replied passionately, "there ain't nothing wrong with them' turnstiles! People been using 'em all day! You seen it for yourself!"

"It's voodoo, that's all," said H.M.

"Pop, you be quiet Jake, there's a coil of rope over there against the tile wall." The policeman pointed to it "You tie one end of that rope to the bars of your window, and the other end to the iron post at the end turnstile over at that side. Nobody gets through until... get going!"

Officer O'Casey, supervising the lying of the rope, was slowly losing his mind.

"Looky here, son!" H.M. told him in consoling tones. "Let's face it! If you know the password, you can get a free ride in the subway. You don't even have to crawl over or climb under."

It was unfortunate that H.M.'s powerful voice carried these words, or a part of them, out over a boiling and swaying crowd. Scattered words rose and were audible above the crowd, like the spurts of small skyrockets.

"What are they doin', anyway?"

"Didn't you hear it? The subway's hoodooed."

"You get a free ride in the subway," a voice was heard clearly to say, "if you care to leap the turnstile or crawl under it."

An electric tremor ran through the crowd. Though a dozen hoots and catcalls greeted the remark, the news spread.

"I assure you, sir," cried the little man who was honestly repeating what he thought he heard,

"you get a free ride in the subway!"

"That's gospel truth!" shouted a travelling salesman who wanted to get out of the mob. "If s a psychological experiment."

"And all you've got to do is get the hell over the turnstile?"

"Yes!"

"Then what are we waiting for? Let's go!"

And the crowd, converging from two directions, crashed forward.

There are certain moments when the chronicler, accurate though he is compelled to be, would prefer to shudder and draw a veil. Besides, established facts here are meagre.

It was not a crowd; it was a tidal wave. As the rope broke, it yanked the grilled window out of the money booth with a clang like the gong for round one. Nobody could afterwards agree who started the fight, though interlocked bodies were rolling down the stairs from the first.

It is unquestioned that somebody dived through the open cash window and began to scoop up money. But all that could be seen of him was the seat of a pair of blue denim trousers, at which some old lady was savagely walloping with an umbrella. Officer O'Casey, swept backwards, tripped over H.M.'s bag and lay stunned. Sir Henry Merrivale (to quote his own words) was merely standing there, as good as gold, not bothering anybody.

What happened was that a sinewy hand, appearing out of the crush, gripped his arm. Under a squashed felt hat appeared the green

eyes of Cy Norton. "Come on!" said Cy.

"Well, lord love a duck!" thundered H.M., above the racket and din. "Son, I didn't even know you were here!"

"Within ten minutes," said Cy, "I can tell you where you’ll be. You'll be in the can, sir; and you'll stay for thirty days."

"I've got a travelling bag back there," protested the injured one, who was being hauled forwards. "I got a very valuable cap, too."

"We can get them later. Forward towards the arcade!"

And the double battering-ram, both heads down, plunged for the arcade.

When they emerged into it, another crowd - mere spectators—fortunately had assembled. It was easy to mingle innocently with it. But Cy, when he saw two more policemen hurrying towards the centre of riot, thought it best to drag H.M. into an adjacent drugstore with a convenient exit.

It was peaceful in the drugstore, despite a crowded soda fountain. Cy, restraining a natural sympathy, quieted the great man.

"Listen!" he urged. "Your valuable papers: passport, letter of credit, the rest of it—have you got them on you?"

H.M. significantly tapped his breast pocket

"Good! Then there's only the question of your suitcase. Do you know anybody who's influential in this town?"

H.M. reflected.

"I know the District Attorney, son. Bloke by the name of Gilbert Byles. He wrote me a letter before I left home. It began, d'ye see, with: 'How are you, you old s.o.b.?' So I knew, American style, it was friendly."

Cy Norton uttered a sigh of relief.

"Then you'll probably get out of this business," he said, "without any trouble. Ill just have to risk coming back and getting your suitcase later. In the meantime, before they send out a police alarm, I've got to get you to Maralarch instead of Washington. I've..."

Abruptly Cy stopped.

Facing them from a little distance ahead, with a hesitant look, was a slender girl in a sleeveless white silk frock. Her face wore a faint golden tan which heightened the intensity of her blue eyes and partly open mouth. Her hair, a natural gold and worn in a long page-boy, gleamed under lights and humming fans.

For a second Cy Norton was more than taken aback. He was shocked to the heart at her resemblance to... And here Cy shut up the thought in his mind. It wasn't a close resemblance. But it was there.

The girl, for her part, was looking at H.M. after the fashion of one who considers a carefully memorized description.

"I—I beg your pardon." She took a step forward. "Are you by any chance Sir Henry Merrivale?"

H.M. coughed and gave her a modest bow.

"Burn me, but you're a nice-lookin' wench!" he said in frank admiration. The girl, though she did not move, seemed to reel. "This country," added H.M., "Is full of nice-lookin' wenches, though half of 'em are so spoiled they ought to be walloped. You oughtn't to be walloped."

The girl seemed to restrain a wild desire to laugh in his face.

"Thanks awfully," she murmured. "I’m Jean Manning. My father sent me here to look for you, because Mr. Davis had to go back to his office." Her eyes grew concerned. "For some mysterious reason, he seemed to think you'd be in trouble. Are you in trouble? I've got a car here."

"You've got a car?" demanded Cy.

"Yes!"

"Where is it? I mean, can we get at it quickly?"

"I know a good deal about this station," said Jean in a curious tone. Then her tone changed at the urgency of Cy's manner. "For one thing, I know a passage off the mezzanine that'll take us out of here as far as Forty-sixth Street and Park Avenue."

"Then we'd better get started for Maralarch, Miss Manning. I'm sorry, but it's serious. If they send out a police alarm..."

"Police alarm?" cried Jean.

"Yes... Oh, no, you don't!" said Cy, seizing H.M.'s coattail just as the latter, his eyes fixed greedily on the soda fountain, was about to get away. "I’ll deliver you out there if it kills me. And you'll answer some questions on the way!"

"Oh, my son!" groaned H.M. "We're safe now. There's no possibility..."

Then, as though warned by telepathic instinct, his big bald head swung round.

Through the glass door of the drugstore, mouthing like an avatar of vengeance, peered the face of Officer O'Casey.

"Out the other entrance," shouted Cy Norton. "Run!"

3

H.M. answered no questions until the big yellow car, having maneuvered cross-town, was racing along the West Side Highway past the Hudson.

Jean, a red scarf round her head, was at the wheel. H.M., his arms folded and a mulish expression on his face, was squeezed in between Jean and Cy Norton on the outside. Cy made one trial effort

"Now look here, H.M. About your going on the razzle-dazzle this afternoon..."

"I'm bein' kidnapped," said H.M., staring malignantly at the windshield. "I got to visit a family in Washington."

The top of the car was down. Though the heat had lessened, its stickiness remained despite a cool breeze. On their left the expanse of the river was dark blue, stung with light points. On their right, far above, the apartment houses of Riverside Drive showed grey as Italian villas against green.

Cy, not a little uneasy, did not speak again until they reached the George Washington Bridge and raced on past.

"There's been no police alarm," he said. "Nobody there as much as glanced inside the car."

"I know!" nodded Jean. "But every minute I've been watching the rear-view mirror, and expecting to hear sirens behind us. And all because of "

"Now, H.M.!"

"Oh, for the love of Esau!"

"You're not being kidnapped," Cy declared violently, "because you never wanted to go to Washington at all."

"I dunno what you're talkin' about."

"And I'll prove it," persisted Cy, "on the basis of your own conduct. Now you knew perfectly damned well how that shuttle worked. Didn't you?"

"Well... now," muttered the great man uncomfortably.

"Somewhere, probably aboard a ship, you learned the trick of how to walk through a turnstile without paying your fare." Cy swallowed hard. Curiosity seared him as it had seared Officer O'Casey. "How did you do it, by the way?"

"Aha!" said H.M. The ghost of an evil glee stole across his face; then again he became the Iron Man.

"That trick's a beauty," he added as a teaser. "Maybe I'll explain how it works, and maybe I won't. But it's a beauty."

Cy restrained his wrath.

"So you couldn't wait," he pointed out, "to try the trick on somebody. You hared off to Grand Central, and sat on your bag like..."

"Like a spider," supplied Jean.

'That's it! You waited like a spider for some likely victim, and along came that motorcycle cop. It was all serene at first But he said Winston Churchill was an American, so you got mad and decided you'd really give him the business. Isn't that correct?"

"By the way," thundered H .M., "did I introduce you two to each other?"

"As a matter of fact you didn't," smiled Jean, with a sidelong glance.

"Think of that, now!" said H.M., as though by mere power of voice he could divert questions about other matters. "Well, this here is Jean Manning, the daughter of an old friend of mine. This feller here," he tapped the opposite shoulder, "is Cy Norton, who's been London correspondent of the New York Echo for eighteen years. There, now!"

"How do you do?" said Jean gravely. And, to tell the truth, it did momentarily divert Cy.

All the time he had been conscious of Jean, too conscious of her, because of that resemblance to someone else. Jean was younger, of course, and less sophisticated. But the memory of other years...

"No longer the Echo's correspondent," he said. "They fired me three weeks ago."

"What's that, son?" HJM. asked very sharply. Jean hesitated. "But why did they... let you go?"

Cy Norton looked wryly back at his life. "Probably," he said half seriously, "because I wasn't much good."

"I don't believe that!" declared Jean. "Why was it, really?"

The car hummed with softness and power. Cy was conscious that he looked older than his age, that he probably needed a shave, that the old soft hat he had bought years ago on Bond Street must look out of place—as he himself felt out of place-in his own country.

"Why was it?" insisted Jean.

"Oh, I don't know. While I was waiting to find the maestro here, I thought of several reasons. But there's still another."

It was one of the few things on earth which could make Cy Norton furious. He must remember, Cy reminded himself, to speak quietly.

"I hate the guts of the Labour Party," he said. "I didn't bother to disguise it The owner of the Echo, here in New York, is one of those 'liberals' who like to praise what they don't understand."

Then Cy grinned, the suffusion of blood retreating from his face.

"But it doesn't matter anyway," he added, "and I'm probably wrong. What I want is information from H.M. Look here, sir. Any traveller, let alone one who knows this country as well as you do, would have known how to get to Washington. Why weren't you playing your monkey tricks at the

Pennsylvania Station instead of at Grand Central?"

Unexpectedly H.M. lowered his defences.

"All right, all right,"he growled. "It wasn't that I didn't want to go to Washington. I've got to go there tomorrow. If d be impolite if I didn't Am I ever impolite to anybody, you stinkin' weasel?"

"No, no, of course not!"

"Well!" said H.M. "And isn't it at Grand Central that you get a train for this place called Maralarch?"

There was a long silence, while the hum of the car sang softly.

"Then you were coming to visit us all along?" asked Jean. A new expression, troubled and almost terrified, drew colour into her face. "Do you mind if I ask why?"

"Because," said H.M., "I got a radiogram aboard ship from your old man. Would you like to see it?"

Fumbling in a capacious inside pocket, H.M. produced the radiogram and held it so that both Jean and Cy could see. The letters seemed to jump out at them.

WHY NOT VISIT ME AT MARALARCH WESTCHESTER COUNTY ONLY TWENTY-ONE MILES FROM NEW YORK WILL SHOW YOU MIRACLE AND CHALLENGE YOU TO EXPLAIN IT.

H.M. Put away the radiogram. Cy repeated aloud the significant words. "Will show you miracle and challenge you to .

explain it" Then Cy whistled.

"I wonder!" he said. "I don't know whether you've heard it, Miss Manning..." "Jean, please."

"All right, Jean. I don't know whether you've heard it, but Sir Henry here is the English detective expert on locked rooms, impossible situations, and miracle crimes."

"Crimes?" Jean exclaimed suddenly. "Who said anything about crimes?"

"Sorry, I didn't mean that I was only making comparisons."

"But why did you say.. ."Jean stopped. Despite herself, she could not keep out the personal. "Do you know," she added, "you look a lot like Leslie Howard?"

Cy closed his eyes. "Oh my God," he murmured.

Jean stiffened. "Have I said anything I shouldn't, Mr. Norton?"

"No. And I wasn't desparaging Leslie Howard. Everybody in England felt a personal loss when he died. But that was because he was a great patriot and a good fellow.... It's these damned films. Must your whole outlook, your whole thoughts and standard of values, be governed by such cheap nonsense?"

Jean's face was flaming under the golden tan.

"But a great film, with real art in it..."

"Jean," he said gently, "the film in general bears about as much relation to art or integrity as a comic book bears to a Rembrandt Can you really swallow a standard of moralities called

'policy,' which would sicken Tartuffe?"

"But they've got to appeal to all types of mentality!"

"Have they?" inquired Cy with interest. "God love them!"

"Oh, you talk just like my father!"

"If that's true, Jean, it's a great compliment Your father is one of the finest men I've ever known."

"Is he?" demanded Jean. The steering wheel wobbled in her hands, and she blurted out "Oh, this is awful!"

"Easy, my wench," H.M. said quietly.

They were nearing the Henry Hudson Bridge over the Harlem River. By tacit consent, when Jean stopped the big yellow car, Cy Norton went round and replaced her in the driver's seat.

"Dad's changed!" said Jean, and put her hands over her eyes. "He's changed!"

"How has he changed?" asked Cy.

"In the first place, he's running around with an awful woman, and I mean a really awful woman, named Irene Stanley. And now—well, I don't understand business things, but they say he's been embezzling from the Manning Foundation, and they say he may go to prison."

Over the Harlem River the sky was blue-white, its edges touched with black. The smell of a thunderstorm, distant but stirring in this humid air, crept past them as they crossed the bridge.

"He thinks the world of you, Sir Henry," Jean observed suddenly. "What’s your opinion about the whole situation?"

And they were aware, as they looked across at H.M. now on the other side of Jean, that the atmosphere had changed too. This was no roaring figure who caused riots in subways. This was the Old Maestro.

‘I'see, my wench," said H.M., still holding the fluttering radiogram, "when I got this message today I thought it was a kind of joke, very fetchin' and fascinating. 'Ho?' thinks I, 'then Fred Manning thinks he can do a miracle?'"

"But what did he mean by that?" cried Jean.

"I dunno—yet. Anyway, I thought visiting him would be like visiting the Polo Grounds or (hurrum!) a friend of mine in the Bronx. But it's not that, my wench. It's dead serious."

Again there was a long silence.

"What do you think about..." Jean stopped. "Do you think Dad's really—oh, how can I say this!—that he's turned into some kind of crook?"

"No!" roared H.M. "I wouldn't believe it even if I saw him standing trial."

"Agreed." muttered Cy Norton.

H.M.'s sharp little eyes swung round behind the big spectacles.

"What's more, my wench, something's upset you and put you into this state of mind. What was it?"

Jean, evidently knowing she was with friends, poured out the story about the interview in Manning's office, up in that quiet place where even traffic howls could not penetrate. Something in it appeared to interest H.M. very much, though he did not comment.

"Robert Browning, hey?" he muttered.

Jean blinked. "Oh! You mean... well, twice a week when the school's in session Dad goes all the way to Albany to lecture. He's got one course in Browning, and another in the Victorian novelists. Of course he's a hundred years behind the times, but he loves it!"

H.M. put away the radiogram and ruffled his hands across his big bald head.

"How long has this funny behavior been goin' on?"

"Ever since he met—that woman."

"So. Have you met her?"

"Good heavens, no! But I've..." Jean stopped abruptly, as though swallowing.

"Y'see," rumbled H.M., again massaging his head, "Fred Manning was in England when I knew him. I knew he had a family, but not much else. Who are you people? Where d'ye live? What’s your background?"

"But there isn't anything to tell!"

"Sure. I know. You tell it just the same."

"Well, we live in this place at Maralarch. It isn't very big or pretentious. I—I suppose Dad's well-off, but not rich. I—I never thought much about it."

"If you never had to think about it, my wench, he's well-to-do. Uh-huh. Go on."

Jean puzzled to know what to say, groped in her mind.

"But there's a lot of ground round the house," she went on. "Dad built us a swimming pool at the back. Then there are some woods, and then Bob's baseball diamond—that's the end of our property—and then an abandoned graveyard that nobody can touch because of laws or something.''

Cy Norton, out of the corner of his eyes, watched Jean's short nose and broad mouth and the curve of her yellow hair.

"My sister," Jean rattled on, "is twenty-four.' Crystal's just got her third divorce. She's very pretty, not like me, and terribly clever. And she's very socially minded, which none of the rest of us are." Despite herself and her brimming eyes, Jean started to laugh. "Sir Henry, I can't wait to see her face when she meets you!"

H.M. somewhat misunderstood this.

"Well... now!" he disclaimed, with a modesty which would not have deceived a baby. "I got a natural dignity, d'ye see, which sort of overawes people until they know me. You were saying?"

"Bob, that's my brother, is the middle one," said Jean. "Bob is twenty-two. He's awfully nice. But he's not clever like Crystal. He's not interested in much except baseball and automobiles. He doesn't know what to do now he's left college. Sometimes Dad is in such a quiet fury with him that I—I could murder him!"

H.M. looked at her curiously.

"Which one could you murder?" he asked. "Your brother or your old man?"

"I—I meant Dad. Not really, of course."

"I see. Anybody else about the place?"

"No. Wait, except for old Stuffy! He's one of the three servants. He's supposed to be houseman, but he does everything from running the vacuum cleaner to massaging Dad's knee. Ages and ages ago he was supposed to be a great baseball player"—here H.M. gave a slight start—"but you'd have to ask Bob about that." Jean paused. Then her voice grew almost hysterical.

"What else can I tell you?" she cried. "We're just an ordinary family!"

H.M.'s gaze, which can be as disconcerting as the evil eye, was turned steadily on her.

"You can tell me this," he answered. "What are you afraid is goin' to happen?"

"I don't understand!"

"You do understand." H.M. spoke patiently. "After that row in your father's office, what are you afraid is going to happen?"

Jean smoothed her skirt over her knees. She looked upwards, as though for help from the sky, and then down again. Cy Norton was intensely conscious of the touch of her arm. Then Jean spoke.

"When Dave and I went to Dad's office this afternoon..."

"Dave," interposed H.M., "being this feller Huntington Davis? Your fiancé?"

"Yes. He's wonderful! He looks just like..." About to quote a film comparison again, Jean glanced at Cy Norton and gritted her teeth.

"Anyway," she went on, "I spoke to Miss Engels, Dad's secretary. She said he'd gone to the Token Bank and Trust Company, and wouldn't be at his office until after lunch. When he did get back, he was carrying a brief case that positively bulged."

"Well?"

Jean swallowed.

"Suppose he is in trouble?" she asked. "Suppose he's going to disappear with a lot of money, and take this dreadful woman with him?"

"But where would be the miracle?" demanded Cy.

"Miracle?"

"He's promised to show H.M. a miracle and challenged him to explain it. There'd be no miracle about running away. Unless," said Cy thoughtfully, "he means to turn into smoke and vanish before your eyes."

"Stop it!" cried Jean.

Cy begged her pardon. He could not imagine what had put that grisly image into his head. Yet it was so vivid that it lingered, like a phantom in the windshield, before three pairs of eyes.

"You take it easy, my wench," H.M. assured her. "I've seen a lot of rummy things in my time, but I've never seen that and I don't expect to see it."

"I'm not worrying about that," retorted Jean, "because it's silly. But tonight..." She turned to Cy. "You'll stay overnight with us, won't you?"

"Great Scott, no. I can't. I haven't got any clothes with me!"

"Neither has Sir Henry," the girl pointed out. "But Dad's always got plenty of spare toothbrushes and razors for guests." She silenced his protests with an appealing look he could not resist

"Because, as I told you," continued a half-hysterical Jean, "Dad's gathering us together for some kind of announcement he says will shock us. And if he makes a remark like that, he's not joking. He means it!"

"Uh-huh," said H.M. "And when is the shockin' due to take place?"

"Tonight!" said Jean. "At dinner!"

Cy Norton hunched up his shoulders. Westwards, the clouds faintly darkened with coming storm.

4

As another peal of thunder exploded over the house, some five minutes before a dinner arranged for eight o'clock, Crystal Manning paced up and down the drawing room.

Outside the rain was a deluge. The long, low frame house, painted white with green window trimmings, comfortable yet unpretentious, might scarcely have been visible through that rain to anyone who walked up Elm Road from the station. Maralarch, commuters may have noted, is the station between Larchmont and Mamaroneck on the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad.

Lightning threw a ghostly shimmer at the windows of the drawing room where Crystal Manning paced. All the lights were on here, as in the rest of the house.

"Now, really!" Crystal murmured impatiently.

She was shapely and not too tall, understanding well how to use the maturity of body which

accompanied a maturity of veiled dark blue eyes. Her hair was dark brown; under light it seemed black. The great Adolphe said he had created a hair style for her—though the average person, seeing the broad parting and hair drawn down almost past the cheekbones, would have said it was the style of our female ancestors a hundred years ago.

With the names of her three husbands we need not trouble. But we may follow some, if not perhaps all, of Crystal's thoughts.

"Oh, hell!" murmured Crystal.

She hoped, in this storm, that the lights wouldn't go out With a sense of humiliation she wished they had a butler. Admittedly there wouldn't be anything for a butler to do here; but it looked so well.

It was all Dad's fault, of course. Dad could have bought one of those estates which lay eastwards behind the house—beyond the swimming pool and the woods and the baseball field and the old graveyard—one of those estates facing out over the waters of the Sound.

Why not? Dad could afford it! Instead he had even cheated her out of seeing the guest of honour. She remembered meeting Dad on the staircase less than two hours ago.

"Of course," Crystal had murmured, as though mentioning an obvious fact, "we're dressing for dinner tonight?"

"No, my dear. Why should we? We don't dress ordinarily."

Crystal could have screamed.

"You may not remember' she said, half veiling the dark blue eyes, "that we're entertaining rather a distinguished guest?"

"Sir Henry? He can't dress for dinner anyway. I understand he lost all his clothes in a riot at Grand Central."

Crystal wished her father wouldn't make these tedious jokes. She remembered him standing on the stairs a little way up, his face lobster pink from the sun, a twinkle in his eye, his white suit outlined against the panelling.

"He's taking a nap, Crystal, and snoring like a lion full of luminal. Don't disturb him, please. I gave you your instructions over the phone."

Crystal's fingers, with their scarlet nails, began to tap on the newel post of the stairs.

"I don't in the least," she said, "mind acting as your hostess..."

"Thank you, my dear." (Irony there?)

"But I think you might give me a little more consideration than Jean. This—this Anglo-American newspaperman. He's socially presentable, of course?"

"He is," Manning replied grimly. "What is more, he loves books."

It was another sore point, which (thought Crystal) the impressive old devil had deliberately brought up. Across the broad hall from the drawing room was the library, three of its walls lined to the ceiling with second-hand books. If Manning had collected first editions, Crystal could have understood. But they were merely old and often half-ruined books, because her father said he could never be comfortable with a new book in his hands.

Crystal wondered what Sir Henry Merrivale would think of this horrible collection.

‘I shall dress for dinner," she murmured, "of course."

And she did. Crystal wore the black and silver gown which, with her inordinate sex appeal, would have disturbed a Trappist monk.

Now, with the rain sluicing down the windows, in the blue-and-yellow drawing room decorated by another kind of Adolphe, she was at the last point of wrath. She had distinctly let it be known that there would be cocktails and canapes at half-past seven. She had pictured a languid half-hour before dinner, while Sir Henry Merrivale, in flawless evening clothes, sipped a cocktail and spoke lightly of his adventures with tigers in the Simla.

And not a soul had yet turned up.

"Oh, so-and-so!" murmured Crystal, surpassing her previous efforts.

There was a clack of footsteps on the stairs outside in the hall. Crystal stiffened, and languidly settled her gown.

But it was only her brother.

Robert Manning, a pleasant-faced and rather too tall young man, with sandy hair and a touch of freckles, slouched into the room with an air of vague preoccupation. Bob had not troubled to dress for dinner, and the colours of his tie would have knocked out your eye at ten yards.

"Good evening, Bob."

'"Lo, Crys."

Crystal's sweet smile was not hypocritical; she really was well-meaning, but sometimes it grew strained. She indicated the big cocktail shaker, moist-gleaming, and the plates of canapes.

"Have a cocktail, Bob?" invited Crystal.

Bob considered this proposal for a moment.

"Better not," he decided, shaking his head gloomily. "In training, Crys."

"Then have a canape?" Crystal suggested sweetly. "Surely that won't prevent you from hitting a bunt for three hundred feet?"

"Look, Crys, don't you even know what a bunt is?" Bob asked. Automatically his fingers closed round the grip of an imaginary bat, and his brown eye gleamed. "You lay it down, like this, so that the runner on first can ..."

"One moment, dear!" said Crystal, and raised her hand. Her heart beat quickened. The guest of honour was arriving.

Three men entered the room. The first must be Mr. Norton, who (Crystal instantly decided) looked like Leslie Howard. She saw her father's silver grey hair, worn rather long but cropped up short beside the ears. Then...

At her first sight of Sir Henry Merrivale—in plus fours, with his spectacles drawn down on his broad nose—Crystal could not have been more startled if one of the Simla tigers had stuck its head round the corner of the door. But she was a clever and quick-witted girl. After all, she couldn't expect him to look like Ronald Colman. And the famous man, the scion of ancient lineage, was in her house.

"And this," her father was saying, "is my daughter Crystal. Sir Henry Merrivale."

Crystal allowed, her dark-fringed eyelids to droop, and smiled.

"Well, stab my bowels," said the scion of ancient lineage, in a voice which must have carried as far as the kitchen, "if you're not a nice-lookin' wench too! Fred, you got a monopoly on nice-lookin' wenches!"

"Oh, Crystal's not so bad," murmured Manning.

Crystal's voice stuck in her throat. She couldn't breathe. What restored something of her poise was what she imagined to be her father's disparaging remark.

"Then you approve of me, Sir Henry?" Crystal drawled.

"Approve of you?" yelled the great man. He leaned forward, and paid her what he believed to be a feverish compliment. "Lord love a duck, I'd hate to see you in an Algiers pub full of French sailors."

"Wh-wh-why?"

"Because," confided H.M., "they'd all cut each other's throats gettin' at you. And that's mass murder." His sharp little eyes fixed on her. "But wouldn't you like to have men killin' each other for your sake?"

Crystal gave H.M. a curious glance, and decided he was—interesting.

"By the way," H.M. confided. "Speakin' of a romp on the sofa..."

Frederick Manning cleared his throat loudly.

"And this is my son," he announced. Bob Manning, tall and gangling and sandy-haired, extended his hand with a sheepish smile. "How are you, sir?"

"I'm feelin' pretty fit, thanks. Looky here! Aren't you the bloke who's interested in motor cars and baseball?"

Bob's face came to life, pleased but astonished.

"Yes, sir. But—don't you play cricket? I mean, of course"—furtively Bob glanced at H.M.'s corporation—"when you were a little younger?"

A faint purplish colour was beginning to creep into H.M.'s face. But he spoke gently.

"We-el!" he said with a loftily deprecating gesture. "I did sort of toy with baseball, son, when I was a lot younger. Nothin' much."

Bob grew eager.

"Listen, sir! Could you come out to the field tomorrow? Moose Wilson's promised to be there." Bob spoke with awe. "The pitcher, you know. He's a grand guy. I know he'd throw you some easy ones if you wanted to practice hitting a little."

"And here," Crystal nodded brightly towards the door, "are Jean and Dave. How nice to see you again, Dave!" Crystal had just been introduced to Cy Norton, and thought him highly interesting— with possibilities. "This is Mr. Norton!"

Jean and Davis, neither in evening clothes, tried to make themselves inconspicuous. For some reason Jean was clutching Davis's arm. Cy Norton shook hands with Huntington Davis, finding him friendly and self-assured, the white teeth flashing against the deep tan—and Cy disliked the man at sight

"But I'm afraid.;said Crystal. Then her voice rose. "Dad!''

"Yes, my dear?"

"We must be very quick with the cocktails. I've ordered dinner for eight o'clock, and the cook is such a tyrant'"

"That doesn't matter, Crystal," said Manning. His low-pitched bass voice always caused silence and attention, when he used it as he used it now.

"Doesn't matter?"

"No, my dear." Manning spoke with polished courtesy. "/ have ordered dinner put back until nine o'clock. I have decided to thrash this matter out before dinner."

A long run of thunder rolled and exploded distantly, but with no less heavy rain. There was nothing in the least ominous in Manning's tone. Yet Jean gripped Davis's arm more tightly, and Crystal opened wide eyes of astonishment Bob, his expression wooden again, did not appear to listen.

"Will you all sit down, please?" requested Manning.

He moved across the blue and yellow room, with its heavy carpet and sat down in a chair under a reading lamp. The particular M. Adolphe who designed this room had included some very peculiar furniture.

Cy sat down not far from young Bob Manning. H.M. swelled his bulk from an out-of-shape armchair. Jean and Davis sat very close together at one end of a sofa; Crystal sat at the other end, near a lamp, so that the light could make the best of white skin and shadows against a low-cut black-and-silver gown.

"No," said Manning, as Crystal made a move. "Don't ring for Stuffy. We can omit the cocktails and canapes for the moment"

Cy Norton, remembering what they had talked about that afternoon, felt a stronger twinge of uneasiness.

"I address myself," said Manning, "to my three children. Naturally I should prefer to do so in private. But there is a reason, which I shall keep to myself, why we must have witnesses."

Manning put his fingertips together, and spoke like a judge from the bench.

"So I ask you three." He paused. "Do you consider that I've always been a reasonably good father?"

The question made Cy Norton want to crawl under a chair with embarrassment It had much the same effect on most of the others, always excepting Sir Henry Merrivale.

Rain spattered against the windows. Crystal was the first to speak.

"But of course!" she exclaimed, with open eyes of wonder under the wings of dark brown hair.

"Y-yes," said Jean, and turned her face away.

Bob Manning still sat and stared woodenly at the floor. At last, and with obvious effort, he contrived to mumble out, "Sure, Dad. You've been great."

"Another question," Manning continued relentlessly. "How many times have you heard of a really perfect marriage?"

"Oh, Dad," cried Jean, "are you going to start again about Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett?"

There was a twinkle in Manning's eye.

"You're quite right," he told Jean. "I might mention Browning or Elizabeth Barrett. But I'll put something else first. You've been kind enough all three of you"—his slight smile vanished instantly—"to give your opinion of me. Now let me tell you what I once thought of you."

He paused a moment

"When you were born, each of you," he went on, "I disliked you and at times I hated you. After your mother died, it took me years before I could become even mildly fond of you."

The shocked silence that followed was as though at the crack of a whip. Manning still spoke quietly.

"Has it ever occurred to you that a really happy marriage can be not spoiled, but badly hurt by these intruders called children? No! It hasn't occurred to you! The sugary sentiment of our day won't permit it

"In the sort of marriage I mean, husband and wife are all in all to each other. They're really in love. They want no intruders of any kind. If they need to have children to bind them together,' they were never happy in the first place. They know a perfect happiness. Well, your mother and I were like that"

There was a small clatter as Crystal upset a cocktail glass.

"My mother.she cried out.

Manning lifted his hand.

"Your mother," he said wearily, "felt much as I did. But she was conscientious. She was a good mother. Until..."

Here Manning glanced across at H.M., as though to explain.

"It was nearly eighteen years ago," he said. "We were on one of those river steamers. Happily alone for once, we thought There was a boiler explosion. Most of the passengers, including my wife, were drowned. I was left with the side of marriage which, rightly or wrongly, I didn't like."

(For God's sake stop! thought Cy Norton. Crystal wont actually care, whatever she says. Bob doesn't likeyou much any way. But Jean! Jean, with her hands over eyes and her look as though she had been struck with a whip!)

At the same moment Huntington Davis, all virtue and respectability, got up from the sofa and walked over to face Manning.

"Forgive me, sir," Davis said. "But are you sure you know just what you're saying?"

"Yes. I think so."

"When people have children," Davis floundered, "they have a duty..."

"I’ve done that duty, Mr. Davis. Three witnesses have just said so, though they're not quite sure about it."

"I mean"—Davis shook his head as though to clear it—"it's our duty to have children, isn't it? What would happen if the rest of the world

thought as you do?" Manning spoke dryly.

"Ah, the old question! Don't let it trouble your sleep." "I insist!..."

"Fortunately, most people are fond of children. Admittedly I am an exception and a bounder. And yet"—Manning whacked the arm of his chair—"if twenty thousand parents could hear my words now, how many of them wouldn't secretly agree with me?"

"You..." Davis began; then checked himself in time. Manning rose slowly from his chair and faced the young man. Both were as erect as grenadiers; they looked at each other, steadily, on dead-straight eye level.

"Dave, come back here!" cried Jean. "Please! There's something I've got to know! Come back!"

Davis complied. But he moved slowly backwards, to show he could still meet the older man's eye. Manning sat down again.

"Listen, Dad!" Jean begged. "All those lovely things you said about mother awhile ago—were they true?"

Her father's voice was gentle. "Every word, Jean. And please remember: I spoke of you all as young children. Not as you are now."

Then—I tried to ask you today, but you evaded it—why must you degrade yourself with this Stanley woman?"

"Because, Jean, eighteen years make too long a time of mourning. The flowers are dead. Miss Stanley is vulgar, yes." An odd, obscure smile twisted Manning's mouth. "But I find her stimulating. Shall I give you Browning?

"What’s a man's age? He must hurry more, that's all; Cram in a day what his youth took a year to hold: When we mind labour, then only we're too old—

What age had Methuselam when he begat Saul?

"Though there will be no more begetting, I hope," Manning added politely that's rather out of its context, isn't it?" Crystal asked, with an effort at casualness. "Browning was a young man when he wrote it."

"And I am fifty-one," smiled her father. "Perhaps two or three years younger than your last husband."

Crystal's face went white. Both she and Bob had pretended not to notice when Jean referred to Irene Stanley.

"We all know, Dad dear," Crystal remarked lightly, "that we can't match you at repartee. But is it really necessary to insult us?"

"Insult you, my dear?" Manning was genuinely startled. "I was not trying to insult you, believe me."

"Then why are you telling us all this?"

"Because," answered Manning, "something will probably happen to me, by tomorrow at the very latest. I want to provide for your future, all of you, in case you never see me again."

5

Now there was dead silence, except for the swirling of rain.

Jean and Davis exchanged glances. Bob sat open-mouthed, looking up. Crystal regarded her father as though this were some sort of joke in bad taste.

"What on earth are you talking about?" asked Crystal.

"Never see us again?" Bob forced out the words incredulously.

"Forget I said that, for the moment," Manning urged. "Try to forget it! Mr. Betterton (you remember my lawyer?) has phoned to say he can't get here until nine o'clock. But we don't need him yet Let's concentrate on providing for the future."

Manning sat back in his chair, his fingertips together, his vivid blue eyes veiled yet his whole imposing presence concentrated.

"Let's take you first, Crystal. You're the oldest"

"Dad, I insist on knowing..." Crystal began shakily. There was a very faint gleam of tears in her eyes.

"I don't think," said Manning, "I need worry about you financially. You, or more probably your own lawyer, can show real genius at getting alimony. If you really want one of those estates at Sandy Reach on the Sound"—he nodded toward the back of the house—"why don't you buy it yourself?"

Crystal was startled. "Buy...?"

Her father laughed.

"You're quite consistent, Crystal," he said. "It has simply never occurred to you, never once in your life, to buy anything for yourself when you could get some man to buy it for you. And yet," he hesitated, "I may be misjudging you, even now. As for you, Bob..."

Bob, hands on knees and gaze on the floor, made an inarticulate noise.

"Look, Dad," he said with an effort. "You don't understand me. I don't understand you. Can't we just skip it?"

"Unfortunately, no. And don't use that damnable term 'skip it'" Manning's voice softened. "You're twenty-two. You must decide what you want to do in life. Why do you say I don't understand you?"

Bob's voice struggled in his throat

"Books!" he blurted out "Books and books and books! If somebody doesn't give a damn about books, you look at him as if he was dirt"